Abstract

Previous work has found that a small number of export superstars contribute disproportionally to the economy’s overall exports. Differently from export superstars, this study is the first to define high growth exporters (HGXs) (that are not export superstars) as a new firm category. We provide their economic importance and depict their micro-level anatomy. By tracking HGXs in Croatia for over a quarter of a century, 44 out of 100 export superstars in 2019 were previously HGXs. HGXs represent only 0.5% of all firms and 18% of high growth firms (HGFs) in the economy, but are responsible for about 25% of new exports and 5% of new jobs. During their growth episode, HGXs hire more employees from technology intensive industries with previous experience in exporting. They often hire on a single year work contract, and more frequently send new employees to work abroad. HGX also increase their presence in more advanced markets, increase the number of new export products and decrease their reliance on the largest product or largest export market. We argue HGXs represent an under-researched category of firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Considerable policy interest surrounds exporters because they are found to be larger firms, more productive, more skill- and capital-intensive, and to pay higher wages than non-exporting firms (Bernard et al., 1995, 2007). In addition, firms that grow via exporting tend not to cannibalize the market share of their domestic rivals, nor engage in domestic business-stealing, but bring in revenues from abroad (Wagner, 2019). Unsurprisingly, there is considerable policy interest in the manufacturing sector (e.g., European Industrial Renaissance, European Commission, 2014), on the grounds of manufacturing’s alleged superiority in terms of exporting, productivity growth, and innovation (Coad & Vezzani, 2019). Policy-makers have introduced a large range of short-term export boosting policies, initiatives to encourage firms to start exporting and deepen their exporting activity (for a review: Srhoj et al., 2023), including public grants, tax credits, subsidized export loans, export credit guarantees, public institutions offering partner search, matchmaking, intelligence, analysis and organizing participation on trade fairs, or providing vouchers for outgoing economic missions, fairs, and external counseling. A special focus of policy-makers is high growth firms (HGFs) because of their contributions to job creation, productivity growth and innovation (Benedetti Fasil et al., 2021). Export growth is a target for HGF policy (OECD, 2013, p. 27, Table 2.7); however, not much research has been done on the intersection of exporters and HGFs. This gap was also recently highlighted by international business scholars who called for more research on scale-ups and scaling in an international business context (Reuber et al., 2021; Tippmann et al., 2023).

Export superstars, defined either as single-largest, top five, top 100 or even top decile exporters by export value have received academic attention (Ciliberto & Jäkel, 2021; Eaton et al., 2008; Freund & Pierola, 2015, 2020). Freund and Pierola (2015) show that top five export superstars contribute to 30% of all non-oil exports in their sample of 32 countries. A narrow focus on export superstars could lead to excluding important and upcoming players in the economy. Export superstars are already perceived as relevant stakeholders, and they seem unlikely to have large export growth rates in future, although their small growth rates may already lead to large absolute values in exports or job creation. Due to creative destruction or structural change, export superstars might be displaced in the future. The question is which firms (besides export superstars) can bring about new products and jobs necessary for economic growth. Candidates with the potential to become export superstars include small and medium enterprises (SMEs). However, SMEs comprise over 95% of all firms, which makes it difficult to manage and tailor targeted policies for high growth (Coad et al., 2022; Shane, 2009). Another potential category could be all current exporters except the export superstars; however, these are still a broad category of firms (Wagner, 2007, 2019) of which many will presumably lack high-growth potential. HGFs are another category of firms that could displace export superstars in the future. HGFs are 3–5% of all firms, but are a heterogeneous category, making it difficult to predict which firms will be HGFs next year, and HGFs often lack growth persistence (Coad & Srhoj, 2020; Esteve-Pérez et al., 2022). This paper investigates a category of firms that is more homogeneous and could be effectively addressed by policy measures: high growth exporters (HGXs) not yet being export superstars.

We contribute to the literature in several ways. Despite research on the characteristics of exporters (e.g., Atkin et al., 2017; Bernard et al., 2007; Wagner, 2007, 2012), HGFs (e.g., Benedetti Fasil et al., 2021; Coad & Srhoj, 2020; Esteve-Pérez et al., 2022), Born Globals (e.g., Knight & Cavusgil, 1996, 2004, 2005; Rennie, 1993), and export superstars (Ciliberto & Jäkel, 2021; Freund & Pierola, 2015, 2020), there is scarce literature on firms having high export growth. We define the category of HGX, which is a sub-category of high growth firms (HGFs) not yet being export superstars, and track these firms over time to investigate whether they become export superstars. In detail, we elaborate differences of HGXs compared to HGFs not categorized as HGXs, to export superstars and to remaining exporters that are not belonging to the category of HGF. HGXs appear worthy of more academic and policy attention.

Our results show five cross-cutting themes. First, HGXs are dynamic and global: growing fast, hiring fast, introducing new products, expanding into new markets, and placing employees abroad. Second, there is some evidence that HGXs are relatively knowledge intensive, being more active in medium-tech or high-tech sectors such as manufacturing, information and communication technology (ICT), R&D-intensive sectors, and knowledge-intensive services (KIS). Third, HGXs hire from other former HGXs and offer more short-term contracts on average. Flexible labor arrangements may benefit HGXs in terms of facilitating the reallocation of talent between HGXs, as well as facilitating the placement of employees in relatively precarious roles. Fourth, HGXs are not growing by concentrating on products or export markets. HGXs are not growing vulnerable, instead their growth involves reducing their reliance on individual products and export markets, and diversifying their sales portfolios. Fifth, HGXs are not the stereotypical cost-cutting entrants selling cheap gimmicks, but their growth occurs alongside increases in unit prices. HGXs differ from other exporters in that they have been successful in growing their exporting activity in the EU Single Market, which is one of the largest and most sophisticated export markets in the world. HGXs therefore constitute a genuine competitive threat to incumbents.

The paper unfolds as follows. Section 2 provides a literature review. Section 3 presents the three census datasets used in the analysis. Section 4 presents the mutually-exclusive categories that form the basis of our analysis: export superstars, HGXs, HGfs (i.e., non-HGX HGFs), non-HGF exporters, and non-HGF domestic traders. Section 5 presents the anatomy of HGXs, investigating the HGXs at the firm-level, firm-employee level, firm-product level, and firm-market level. Section 6 discusses the results, academic and policy implications in the short and long-run. Section 7 concludes.

2 Literature review

Three literature streams provide the background for our analysis of HGXs: the literature on HGFs, the literature on exporter dynamics (in particular, the export superstars), and the literature on early internationalizing firms (EIFs, also known as Born Globals).

2.1 High growth firms and internationalization

Export growth is a target for high growth firm (HGF) policy (OECD, 2013), although little research has focused on the intersection of exporters and HGFs. The HGFs literature has mainly considered the internationalization dimension by including additional explanatory variables in a standard HGF regression framework. For example, Coad and Srhoj (2020) show that having higher export growth or higher exports is associated with becoming an HGF in Croatia and Slovenia. Teruel et al. (2022) review several existing articles and suggest that being internationally active in general and exporting in particular are important for HGFs. More closely related to our work, Cruz et al. (2022) find that importing, exporting, foreign ownership, or benefiting from offshore regimes is associated with a higher probability of achieving high-growth status compared to other similar firms in terms of size, age, sector, and region. Cruz et al. (2022) highlight the particularly important role of imports in fueling HGFs. Teruel et al. (2022) use ORBIS and EIBIS survey data for 27 EU Member States and the UK to show a positive association between being an HGF, conducting international activities (particularly FDI), and adopting new digital technologies. While the HGF literature has not focused centrally on the internationalization dimension, the literature on exporter dynamics has made considerable progress while nevertheless not connecting with the literature on HGFs.

2.2 Exporter dynamics

The literature on exporter dynamics is well-established in the field of economics and international trade. Bernard et al. (1995) highlighted the superiority of exporters compared to domestic traders, in terms of size, profitability, capital intensity, productivity, and wages (see also Wagner, 2007). These empirical findings gave rise to new trade theories, such as models that emphasize firm heterogeneity in productivity in markets with trade costs that allows the most productive firms to become exporters (e.g., Melitz, 2003). New datasets enabled delving deeper into exporter dynamics. Therefore, this new empirical literature stream used new datasets to analyze the changes between and within exporters, leading to a rich set of stylized facts and empirical regularities.

Most firms sell only in the domestic market, and exporters usually export to a single foreign market, while only a minority of exporters export to many markets (Eaton et al., 2004). Eaton et al. (2008) report many interesting findings from their analysis of Colombian customs data: (i) about one-third to one-half of all exporters are new exporters in a given year; (ii) these new exporters contribute little to aggregate export growth or decline (either because they are tiny or because they do not export for more than a year); (iii) among firms surviving in export markets, export growth is especially large in the initial years, particularly in the first 3 years, after which export growth diminishes; (iv) a switch from non-exporting to exporting usually comes from gradually adding markets (i.e., starting with a single market, and then gradually increasing in number of export markets); (v) firms usually start exporting small quantities to a neighboring country; (vi) exports increase gradually by increasing presence in current export markets, while a sizable fraction of exporters expand to other export markets. Eaton et al. (2008) showed that exports growth is highest among new firms and firms in low-exports quintiles, because such firms are tiny, and subsequently their contribution to aggregate growth is trivial. Firms in the high-sales quintiles had low growth, but their contribution to aggregate growth was considerable. Eaton et al. (2008) provide two potential interpretations of the difference in growth rates. A first explanation refers to increasing resistance in foreign markets as firms’ exports grow, for example, initially firms sell to easy-to-access buyers, and then further growth becomes difficult as demand elasticities fall with sales, or firms encounter capacity constraints in production facilities. A second explanation is that new exporters are tried-out by foreign buyers on a limited scale (cf. Rauch & Watson, 2003), and once this try-out is up, exports stop or increase. Alternatively, new exporters experiment on the market with small quantities to resolve uncertainties regarding product-market fit, and then either stop exports or expand.

Mayer and Ottaviano (2008) use a sample of mostly large firms from seven countries (Germany, France, UK, Italy, Hungary, Belgium, and Norway) to establish several stylized facts on exporter dynamics.Footnote 1 Notably, (i) aggregate exports are driven by a small number of top exporters (i.e., export superstars), (ii) only a few firms have high export intensity (defined as exports as a fraction of total sales), (iii) these high export-intensity firms export to many markets, (iv) exporters are more likely to be foreign-owned, (v) foreign-owned firms generally perform better than domestic exporters, while exporters perform better than domestic traders (c.f. Bernard et al. 1995; Wagner, 2007), and (vi) historical ties such as former colonial links and a common language foster exports, making it easier for less efficient firms to export. A sub-stream of literature on export superstars emerged from the literature on exporter dynamics. Export superstars can have different definitions—including single-largest, top five, top 100, or even top decile exporters by export value (Freund & Pierola, 2015, 2020; Mayer & Ottaviano, 2008). Freund and Pierola (2015) show that top five export superstars contribute to 30% of all non-oil exports in their sample of 32 countries. Export superstars are typically born large and there is interest in their export growth and diversification. Freund and Pierola (2020) use firm-level data on manufacturing sector trade from 32 developing countries and report that, over a 5-year period, the five largest exporters account for around one-third of exports, 47% of export growth, and a third of the growth that comes from export diversification. Within countries and within industries, export growth is positively associated with the share of exports in the five largest firms. Most of the top five exporters were already large (5–8 years earlier) and these export superstars rarely emerge from the bottom half of the firm size distribution. Available evidence suggests that export superstars are producers, not traders, and are mainly foreign-owned.

Lawless (2009) analyzed a sample of 751 firms in Ireland over a 5-year period (2000–2004) and showed that productivity differences can explain firms’ number of export markets. She further highlighted the dynamic nature of firms’ involvement in export markets. Entry into or exit from markets was an important component of overall market-specific export flows, particularly for less popular markets. Lawless (2009) confirmed previous empirical results (e.g., Eaton et al., 2008), showing that the smallest exporters have the highest export growth alongside a tiny contribution to overall exports, while the largest exporters had small growth rates, but contribute the most to the overall exports growth. To put this into numbers, the largest exporters grew 4%, but this was 73% of aggregate exports growth, while smallest exporters grew on average 21%, but this was only 2% of aggregate exports growth. This finding of the relative unimportance of new export entries was also confirmed by Buono et al. (2008) on a sample of French exporters (1995–1999) who also highlight that trade relations are much more stable in more popular export destinations (where firms from France export more often).

Findings that small exporters have high growth rates, while large exporters have low growth rates was also confirmed in Argentinian customs data (2002–2007) by Albornoz et al. (2012), who observe an empirical pattern among a share of exporters—the growth at intensive and extensive margins—and name this pattern sequential exporting. This idea of sequential exporting has important implications for trade policies or export boosting policies (cf. Srhoj et al., 2023). Lowering tariffs or providing export boosting policies will induce some firms to start exporting, and once they learn about their ability to export to a particular market, if successful they will further expand to other export markets. Therefore, initial sunk costs of entering an export market can be worthwhile given the possibility of “sequential exporting.” Albornoz et al. (2012) also find that “sequential exporting” is less evident in the following cases: (i) during export restart following a break; (ii) among firms exporting simultaneously to multiple markets; and (iii) exporters of homogeneous goods.

Eaton et al. (2021) develop a model of firm-level export dynamics focusing on firm’s customer base and knowledge of a market, together with analysis of Colombian data on manufacturers shipping to the United States of America, to show the following three insights. Firstly, most exporters ship a small quantity to a very small number of foreign clients. Secondly, these foreign relationships usually are not long-lived. Thirdly, in each cohort of new exporters, there is a small number of firms that survive and grow several times faster than aggregate exports. The suggested mechanism is not by selling a higher quantity to the same foreign client, but by finding new customers. In other words, firms have to undertake costly search to find potential buyers, and these buyers can reject their product or enter in finite-lived business relationship. When buyers form a business relationship, they send exporters a signal of appeal to encourage them to continue their search for additional buyers (learning effects), in addition, successful business relationships reduce exporters’ search costs by improving their visibility (network effects) (Eaton et al., 2021).

What do firms do to expand the customer base after entry into an export market? This question was investigated by Fitzgerald et al. (2023) on Irish customs data, drawing on two prominent theories of customer base accumulation: (1) firms can reach more customers by engaging in non-price activities such as marketing and advertising, or (2) the future customer base is increasing in today’s sales, so firms can expand in a market by first charging markups below the statically optimal level, and then gradually increase markups as the customer base rises towards a possible “steady state.” Fitzgerald et al. (2023) find export quantities increase (relative to old markets) in the years following export entry, but prices do not increase. They find that investment in the customer base through marketing and advertising (captured by the ratio of advertising and marketing expenditures to sales) explains the dynamics of quantities. Successful episodes of export market entry seem to be associated with important post-entry dynamics of quantities, but not of markups.

2.3 Born globals

Another stream of literature in international business and entrepreneurship focuses on Early Internationalizing Firms (EIFs), also known as Born Globals.Footnote 2

First, who are Born Globals? The term Born Global was introduced by management consultants (i.e., McKinsey & Company; Rennie, 1993). This subgroup of firms is defined as “entrepreneurial start-ups that, from or near their founding, seek to derive a substantial proportion of their revenue from the sale of products in international markets” (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004; p. 124). This definition is usually operationalized based on two dimensions: age and export intensity. The usual Born Global definition (i.e., Meuric & Favre-Bonté, 2023; Kuivalainen et al., 2007; Knight & Cavusgil, 2004; Madsen et al., 2000) refers to firms that have started exporting within the first 3 years after foundation and have an export intensity (share of exports in total sales) of at least 25%. Note that there is nothing in this definition regarding whether Born Globals are actually growing. Some famous examples satisfying this definition of Born Globals include Microsoft, Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook, and eBay. About one-fifth of new enterprises in Europe across sectors are found to be Born Globals (cf. Cavusgil & Knight, 2015; Eurofound, 2012).

Second, what triggers Born Globals (i.e., early internationalization)? Countries with smaller domestic markets have more born global firms, hence the size of the firms’ home market matters (Cavusgil & Knight, 2015). Other important triggers of Born Globals include technological development, changes in production networks, global market conditions (e.g., new niche markets), and organizational capabilities. Fernhaber et al. (2007) find Born Globals are more common in rapidly growing industries, high knowledge intensity industries, and globally interconnected industries.

Third, who leads Born Globals to capture the emerging opportunities? Founders of Born Globals have the vision, commitment, entrepreneurial orientation, and innovativeness to offer high-quality products or services to global markets. Their founders focus on international markets from the beginning (Acedo & Jones, 2007) and also have prior international experience (Criaco et al., 2022). Zahra et al. (2005) highlight the ability of managers to conceive, recognize, and exploit opportunities in foreign markets, which fosters higher proactivity, tolerance for ambiguity, and decreased perceptions of risk in internationalization (Acedo & Jones, 2007; Cavusgil & Knight, 2015). Founders’ motivation for early internationalization is improved performance compared to domestic market-oriented firms, also known as the international premium. The international premium occurs because of learning from and networking with international partners, lower costs of information, lowering uncertainty about foreign markets, and efficient logistics.

Fourth, what do we know about Born Globals’ strategy-making? Harms and Schiele (2012) observe that experienced entrepreneurs are less focused on planning activities (i.e., causation-oriented entrepreneurs), but more on an adaptive and iterative process by looking at available resources and then experimenting with alternative possibilities based on emerging opportunities (i.e., effectuation-oriented entrepreneurs). Cavusgil and Knight (2015) argue that Born Globals tend to follow advances in technology, science, and design and then market the cutting-edge, unique, and innovative offer. It is assumed that Born Globals have the capacity to develop innovation and deliver it in innovative ways (Leonidou & Samiee, 2012). Knight and Cavusgil (2005) suggest different sub-types of Born Globals including: poor performers “stuck-in-the-middle,” entrepreneurs emphasizing cost leadership, high-tech focusers, and entrepreneurial strategy and technology leaders. Born Globals tend to avoid cost leadership and tend to emphasize differentiation or focus as their strategies (Knight & Cavusgil, 2005; 2015). On the one hand, firms with a differentiation strategy usually target niches for which they develop and market distinct offerings. On the other hand, firms with a focus strategy are concentrated on developing superb capabilities in a particular product category or are focused on specific groups of buyers who have high expertise. Previous work (Cooper & Kleinschmidt, 1985) emphasized the importance of being oriented to the world-market as opposed to being oriented towards a “convenient” export market that is geographically and psychologically close. Kuivalainen et al. (2007) divided Born Globals into Apparently Born Globals and True Born Globals, where the first have lower export intensity and export to nearby markets, while the second have high export intensity and export to far-away markets. Kuivalainen et al. (2007) do not find risk-taking or proactiveness (two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation) to be necessarily higher among True Born Globals compared to Apparently Born Globals; however, True Born Globals were higher on another entrepreneurial orientation dimension (i.e., competitive aggressiveness).

Fifth, what is specific about Born Globals’ learning? Born Globals are thought to allocate their resources efficiently under the principle of asset parsimony (Cavusgil & Knight, 2015). They focus on early and rapid internationalization to learn about foreign markets, which is enhanced with social capital and network relationships (Cavusgil & Knight, 2009; Chetty & Campbell-Hunt, 2003). Early internationalization benefits from innovative culture (Cavusgil & Knight, 2015), internal and market-focused learning capability, as well as knowledge gathered from the firm’s network relationships (Weerawardena et al., 2007). Research has identified different types of organizational learning and innovation among Born Globals (Freixanet et al., 2020), and recently, dynamic explanation of the capability development given by Meuric and Favre-Bonté (2023) on a sample of 15 firms in two French regions (Auvergne Rhône-Alpes and Brittany). Related to our paper, Meuric and Favre-Bonté (2023) use a standard HGF definition (OECD-Eurostat, 2007) combined with the Born Globals definition and show that the interactions between three main microfoundations (rapid prototyping, experiential learning, and international strategic agility) generate a feedback loop that allows the HGF Born Globals to continuously gain new knowledge and improve their own products. This feedback loop, composed of the three microfoundations, generates HGF Born Globals’ commercial intensity. The core of growth is suggested to come from the interaction between two microfoundations (i.e., navigating international networks and improving international maturity) which facilitate continuous support for market entries and enhance rapid international expansion (Meuric & Favre-Bonté, 2023).

2.4 HGX as an important new category

While considerable research on exporting firms has been done, we argue the HGX segment remains under-researched.

First, the HGF literature does not analyze exports in depth (Section 2.1). For example, no research has been done on HGFs using customs data (i.e., firm-product-market level), nor is there sufficient research on HGFs and their exporting growth.

Second, in the exporter dynamics literature there are several sophisticated and broad analyses of customs data (e.g., Eaton et al., 2008, 2021); however, the main findings relate to export superstars as a small number of important exporters (Section 2.2) and highest export growth among tiny exporters (Section 2.2). This literature uses quintiles, which is problematic, as there are many tiny firms with exceptional relative export growth of negligible absolute export-size importance. Consider the example of a firm that sells USD 10,000 domestically and USD 1000 abroad, if this firm in the next year sells again USD 10,000 domestically, and USD 4000 abroad, this would make it an impressive 400% export growth of no aggregate importance.

Third, the Born Globals definition focuses on firms that have at least 25% of exports in the first 3 years (Section 2.3). However, this definition faces several drawbacks. On the one hand, while it is well-suited for technology-intensive firms, there are many successful exporters which do not fit the definition. Cavusgil and Knight (2015) highlight some of these: Parker Pen, General Motors, Philips, Sony, and Honda, to which we can add: McDonalds, Starbucks, Hewlett-Packard, L’Occitane, Nokia, Ferrero Group, or Red Bull. On the other hand, about one-fifth of new enterprises in Europe across sectors are considered to be Born Globals (cf. Cavusgil & Knight, 2015; Eurofound, 2012). The Born Globals definition captures many firms with a mediocre performance in terms of economic contribution and job creation (Ferguson et al., 2021). Imagine a firm that makes USD 10,000 a year and exports USD 3000 a year in the third year from its foundation. This firm would be satisfying both criteria for Born Globals, the time dimension (starts exporting up to 3 years from foundation) and export intensity criteria (30% of sales are from exports), but this would be a bad example for a Born Global, and would be exactly the type of firm that Eaton et al. (2008) or Lawless (2009) describe as negligible. The international business literature (i.e., Cooper & Kleinschmidt, 1985; Freixanet et al., 2020; Knight & Cavusgil, 2004; Kuivalainen et al., 2007; Meuric & Favre-Bonté, 2023) avoids this issue by cherry-picking better examples satisfying Born Globals criteria in tiny sample sizes, but an elite firm-type definition should not pick-up tiny and/or non-growing firms. Elements of critique of the Born Global definition and operationalization can be found in multiple studies (i.e., Kuivalainen et al., 2007; Madsen et al., 2000; Moen & Servais, 2002).

Fourth, Cavusgil and Knight (2015; p.3) argue that the “… issue of why some firms internationalize early, others late in their evolution, and still others choose to remain local, is a fundamental question for international business scholarship.” Ferguson et al. (2021) observe no benefits of early internationalization compared to later internationalization, in their comprehensive analysis of Swedish manufacturing firms, 1998–2014. With regards to the firm internationalizations that come with somewhat later firm age, a notable example is Bell et al. (2001) who conduct 50 semi-structured interviews to suggest there are important exporters that do not necessarily satisfy the EIF definition. However, Bell et al.’s (2001) study is exploratory in nature, and fails to provide a definition for a group they call born-again globals (Sheppard & McNaughton, 2012). Thus, we suggest, there is a need for a different definition capturing firm growth in exports independent of firm age.

3 Data

Our analysis focuses on Croatia. World Bank classifies Croatia as a high-income country since 2017, and prior to 2017 as an upper middle-income country. Historically, Croatia fought its war for independence and became an internationally-recognized independent country in 1992. Prior to independence, Croatia was part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, an economy which was organized as a mixture of a planned socialist economy and a market socialist economy (Horvat, 1971, 1986). After independence, Croatia transitioned to an open market economy and became part of the World Trade Organization in 2000 and of the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) from 2002 to 2013. Since July 2013, it became an EU Member State, therefore part of the EU Single Market and no longer part of CEFTA (Josic and Basic, 2021).Footnote 3 Policymakers in Croatia have shown considerable interest in supporting exporters, with studies documenting mixed success (e.g., Srhoj & Walde, 2020).

In 2019, Croatia’s exports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP were 57%, considerably above the world average of 28.2%, or OECD member states’ average of 28%. This indicator was already high in Croatia since its first measurement (1995, 27.2%), while the world and OECD member states averages were at 20.9% and 18.7%, respectively. Merchandise exports to high-income economies as percentage of total merchandise exports in Croatia was 79.9% in 1995 and 74.1% in 2019, while these figures were 76.9% and 68.2% for the world and 79.6% and 75.6% for the OECD member states averages. Medium and high-tech exports as a percentage of manufactured exports in Croatia was 37% in 1995 and 48% in 2019, which is more than in Australia (19%), Russia (27%), India (37%), or Brazil (39%), but less than in Italy (54%), Spain (55%), Belgium (56%), or the USA (64%).Footnote 4

Although several indicators of the Croatian economy suggest findings can be generalized to other countries, we are cautious about generalizing our findings due to Croatia’s historical peculiarity. To address the issue of generalizability, most of our analysis is calculated for the period after entering the EU. Our initial study of HGXs should trigger further research to replicate or extend the generalizability of the economic importance of HGXs.

The following subsections outline the micro-level datasets.

3.1 Firm financial data

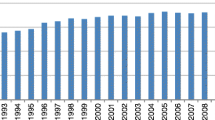

Firm demographic and financial data come from census data stemming from the Financial Agency (FINA) of Croatia. This dataset encompasses all publicly-listed and private limited companies incorporated in the Republic of Croatia. It includes full balance sheet and profit and loss statements of firms including information on firm employees, firm sales, imports, and exports,Footnote 5 along with demographic information such as firm employment, age, NACE 4-digit industry, and micro location of the firms’ headquarters (i.e., county and municipality). This full panel census data includes 2,297,130 observations and 234,176 unique firms with 410 variables over the period 1993–2019.

3.2 Firm product data

Firm-level international trade data stems from the Customs Administration, Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Croatia, and was assembled by the Croatian Bureau of Statistics (DZS) and accessed in the DZS safe room. The Customs Administration data encompasses all imports and exports of goods disaggregated at the firm–market level encompassing the period 2008–2016. The variables include firm ID, the 8-digit Combined Nomenclature (CN8) product codes, the country market to which a firm exports or imports (i.e., destination market), together with amount of exports in tons and value of product exports of a firm in a particular market. To illustrate with a fictional example, we could identify a firm “Car Equipment Ltd.” which exports to the USA, 500 tons of batteries, with a value of 5,000,000 euros. CN8 product codes change over time and harmonizing product codes over time is needed in order to measure the number of exported products (or newly introduced products, and the value of new products) in a valid way (Baumgartner et al., 2023). We use the Harmonizer package in R (Baumgartner et al., 2023) to harmonize CN8 product codes over time. Finally, we enrich this data with information on bilateral distance between Croatia and the destination market, whether a destination market is a European Union (EU) Member State, CEFTA market, or other market (CEPII GeoDist database, Mayer & Zignago, 2011).Footnote 6

3.3 Firm employee data

The employer–employee dataset stems from the Croatian Pension Insurance Institute (HZMO). Pensions are mandatory in the Republic of Croatia, and HZMO tracks all pension registrations that are either started or ceased; i.e., we have a census firm–employee dataset. Importantly, the employee is anonymized, but in a structured way so that we can track employees changing jobs over time. While employees are anonymized, the data includes variables such as start of work at the job, type of work contract, the date of work contract termination, reason for termination, employee occupation, qualifications and education, gender, and age. In addition to these variables, the firm ID of the firms in which each employee works is also included. This full panel census data includes 6,329,064 observations, 312,769 unique employersFootnote 7 and 2,009,420 unique employees over the period 2014–2020.

We used these three rich data sets for our analyses, albeit with the limitation that the time periods do not fully overlap. To show the number of HGXs and their transitions to export superstars, we have the full period from 1993 till 2019. Most importantly, for describing the economic contribution and firm-level features of HGXs, we used the period 2013–2016 (for which product-level data was also available). Replicating the results for the period 2016–2019 yields further insights into the economic contribution and firm-level characteristics of HGXs. Furthermore, to examine HGXs’ hiring practices, we obtained the firm-employee level data for the period 2016–2019, as this data did not exist in a structured form before 2014.

4 Definition of firm categories

This study specifies several firm categories and defines the category of high growth exporters. Figure 1 illustrates the five mutually exclusive firm categories. Export superstars are defined as top 100 firms by export value in period t (category (i)).Footnote 8 All other firms, i.e., the ones not being an export superstar, we classified into high growth firms (HGFs) or non-HGFs.Footnote 9 Our high growth firms (HGFs) definition aligns closely with the OECD-Eurostat (2007) definition of the revenue-based HGFs, except that we use a more inclusive lower-bound size threshold of 5 employees instead of 10 employees, because of concerns in the literature that the threshold of 10 employees could be overly restrictive (Daunfeldt et al., 2015). HGFs are defined as firms having 5 or more employees and an average yearly sales growth rate of at least 20% over three consecutive years, i.e., \(\frac{{S}_{t+3}-{S}_{t}}{{S}_{t}}\) ≥ 0.728, where St denotes sales at time t.Footnote 10

All HGF firms are divided into (ii) high growth exporters (HGXs) and (iii) the other high growth firms which are not HGXs (abbreviated as HGfs). Within the category of HGFs, HGXs are firms whose sales growth is driven by the growth of exports, i.e., firms for which a share of at least 50% of the minimum yearly sales growth by HGF definition is generated by exports. Thus, the additional criteria

where \({X}_{t}\) denotes export at time t, holds for HGXs. We chose 50% as the percentage because we wanted a substantial part of the growth to be due to growth in exports. The chosen approach does not exclude the possibility of becoming an HGX if an HGF does not export in the first period of interest (t).Footnote 11 All other HGFs that fail to satisfy the HGX definition are HGfs.

Among the firms not being export superstars and failing to satisfy the HGF definition, we further classify these firms into (iv) non-HGF exporters and (v) non-HGF domestic traders which do not export. The main analysis does not focus on domestic traders because the literature (Bernard et al., 2007) already answered many questions related to the difference between exporters and domestic traders (non-exporting firms). With this approach, we obtain five mutually exclusive categories for investigation: export superstars, HGXs, HGfs, non-HGF exporters, and non-HGF domestic traders. Figure 1 presents the various (mutually-exclusive) categories of firms and their connections.

Finally, firm entries and exits are important for job creation and innovation (Haltiwanger et al., 2009), which is why we considered firm entry and exit for calculating the number of jobs and the exports creation of different types of firms in the economy. Given the 3-year period that features prominently in the OECD-Eurostat (2007) definition of HGFs, firm entry is defined as any firm that does not exist in period t but exists in period t + 3, while firm exit is defined as any firm that exists in period t but not in period t + 3.

Figure 2 shows the number of firms per firm type for each of Croatia’s 21 NUTS 3 regions per 10,000 residents. Regardless of the mutually-exclusive category of firm (HGXs, HGfs, non-HGF exporters, and export superstars), the highest shares are documented in the capital city probably due to agglomeration or spillover effects (Puga, 2010; Roca & Puga, 2017). The north-west regions bordering Slovenia, which also has a history of exporting and higher shares of exporters (Bačić & Aralica, 2016) have higher shares of HGXs. These Croatian regions have strong international ties to Slovenia, Austria, Germany, and Italy (Croatian Chamber of Commerce, 2018). Dalmatia (coast, south-west) and Slavonia (continent; north-east) have very low shares of HGXs, but also have low shares of non-HGX exporters and export superstars. South Dalmatian regions (i.e., Dubrovnik-Neretva and Split-Dalmatia) have very high shares of HGfs-these regions are tourism-intensive with HGfs stemming from sectors such as construction, accommodation, restaurants, and beverage service activities.

5 Results

Starting from 1995 until the last pre-pandemic year (2019) for each of the eight 3-year periods (Fig. 3), we used the definitions and classified firms into the corresponding categories (i.e., Fig. 1).

In each 3-year period, there are 100 export superstars, thus, 800 export superstar observations with 290 unique export superstars over the period, while there are 2515 unique HGXs. Compared to export superstars, HGXs are more volatile. From the 100 export superstars in 2019, as many as 44 were previously HGXs. Depending on the decades, 5% of export superstars in 2019 were HGXs in 1990s, 21% were HGXs in 2000s, and 26% were HGXs in the 2010s (details in Table 15).Footnote 12 Additional analysis shows that the largest export superstar was previously not an HGX in the period 1995–2019, but was large already at the start of the analyzed period and did not come from the low-end of the firm size distribution. Among the top five largest export superstars, two export superstars were previously HGXs. With 44% of export superstars in 2019 having been HGXs, we conclude that previous HGXs have a chance to become export superstars over a long enough period. This chance may even be higher when targeted by policy but this needs further research. In other words, current HGXs are potential future export superstars which give additional motivation for further investigating their characteristics in comparison to HGfs, export superstars, and non-HGF exporters.

5.1 Sector distribution

We examine the industrial differences among the firm categories in the period 2013–2016 (Table 16). To some extent, differences in the within and between distributions of sectors dependent on the firm categories are expected for tradeable and non-tradeable sectors. Export superstars (63%) and HGXs (31%) are predominantly in the manufacturing sector. HGXs are more frequently in the transportation and storage sector (9%) than HGfs (4%), but similar to non-HGF exporters (7%) and export superstars (6%). Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles is a sector where there is considerable share of HGXs (13%), but less than HGfs (20%) and non-HGF exporters (28%), with a similar share to export superstars (13%).

HGXs are actually more frequently in the information and communication technology (ICT) sector (15%) than HGfs (3%) and non-HGF exporters (10%), while there are no export superstars in ICT in 2013. Similarly, HGXs (9%) are more active in professional, scientific, and technical activities than export superstars (1%), similar to HGfs (10%), and less than non-HGF exporters (17%). There are many HGfs in the construction sector (23%), but far fewer HGXs (8%), non-HGF exporters (4%), and export superstars (1%). A similar distribution occurs for the period 2016–2019 (Table OA1) with a noticeable increase of HGXs in ICT, as well as emergence of an ICT export superstar in 2016.

5.2 New exports

Table 1 provides insights into the net export creation of active firms in 2013, and their additional exports 3 years later (2016). HGXs are only about 0.5% of all the firms in the economy, they account for 24.9% of export growth (1456 out of 5841 million euro), while considering only the active firms (excluding firm entry) HGXs account for 28.8% of export growth. HGXs are 18.6% of the number of HGFs (528 out of 2846) and account for almost all of the export growth of HGFs (1456 out of 1562 million euro). HGXs have about 2.5 times the exports as HGfs in 2013, despite being only about 23% of HGfs by number. By the end of the growth period (i.e., 2016), HGXs have almost 10 times more exports than HGfs. In absolute exports value, in 2013, Superstars are almost 20 times larger than HGXs (6013 vs 309 million euro). The difference between the Superstars and HGXs falls by the end of the growth period (i.e., 2016) to 3.3 times (5789 vs 1765 million euro). Table OA2 repeats the analysis in Table 1 for the period 2016–2019, finding qualitatively the same results.

In the period 2013–2016, the 528 HGXs contribute more to the overall export growth than the 91Footnote 13 export superstars (24.9% vs 16.5%, respectively), firm entry contributes 13.6% of new exports, and the rest of the contribution to new exports essentially comes from slow-growth non-export superstar firms. The contribution to exports from entries (793 million euro) is larger than the loss due to exit (−689 million euro). Export superstars decline in exports (−3.7%) while the “other active firms” categoryFootnote 14 grew (27.8%). HGXs as a group grew their exports by 471%. In 2013, Croatia entered the EU, so the increase of exports during 2013–2016 could have benefitted from the EU accession. We also conduct the analysis for 2016–2019 and show HGXs have a similar absolute growth in exports as in 2013–2016 (1439 million euro in 2016–2019 vs 1456 million euro in 2013–2016).

5.3 New employment

We investigate the job creation of different firm types over the period 2013–2016. Table 2 shows that the creation of new jobs from firm entries is smaller than the destruction of jobs from firm exits (85,470 vs−87,232). There are 32,771 new firms from 2013 to 2016, which are important for jobs in the economy, as they account for about 10% of all jobs (85,470 out of 864,662), and 38.2% of all new jobs (85,470 out of 223,741). HGXs make up a much smaller category of firms, only 528 firms, which make a disproportionate contribution to job creation. In 2016, the 528 HGXs account for about 38% of the number of the 91 export superstars jobs (23,277 vs 59,916, respectively), although when it comes to job creation (i.e., changes rather than levels), HGXs are growing fast (73.3% growth) while export superstars are actually destroying jobs overall (i.e.,−11.9% growth). Table 2 also shows HGXs employ about 28% of the number of HGf employees in 2013 (13,430 vs 48,533), while this percentage grows to 33% in 2016 (23,277 vs 70,392). In relative terms, HGXs have a higher growth rate than HGfs (71% vs 45%).

Since there are 4 times fewer HGXs than HGfs, the HGXs make a disproportionately large contribution to job creation. In particular, HGXs grow on average by 18.6 employees (9847/528), while HGfs grow by 9.4 employees on average (21,859/2318). Relatedly, looking only at the firms growing in employees from 2013 to 2016, HGXs are 0.5% of all firms in the economy but contribute 4.7% of all new employees in the economy, thus about 10 times more than expected considering their number (share of firms in the economy). HGfs are 2.2% of all firms in the economy, but contribute 11.2% of all new jobs, which is about 5 times more than expected by their share in the economy.

Analysis for 2016–2019 (Table OA3) shows similar results to Table 2. During 2013–2016, HGXs create 9847 jobs, while for 2016–2019 HGXs create 11,351 jobs. However, for the period 2016–2019, we also have data on firm-employee spells which allows more detailed analysis. Firm types are merged by firm IDs with firm-employee employment spells in the same period. Differences between HGXs and the other categories are not huge (Table 17 and 18), although a few observations can be made. In particular, new hires at HGXs are more likely to have previous work experience in the mid high-tech sector, and in particular HGXs employ from non-HGF exporters, HGXs, and export superstars. HGXs are more likely to hire employees on 1-year contracts (i.e., short-term) and have considerably more new work contracts for working abroad (20.8%).

5.4 Firm-level characteristics

We summarize firm-level characteristics for HGXs compared to other firm categories using a linear probability model based on variables from 2013 (period t). In this sample, as many as 70% of HGX did not satisfy the Born Globals definition (Table OA4), while the mean export intensity of HGX was 0.40 in 2013, and 0.63 in 2016 (Table OA5). The median HGX sales in year 2013 were € 564,000,Footnote 15 thus, the median HGX had to grow 72.8%–this implies growth to € 974,592 in year 2016; therefore, a growth of € 410,592, from which at least half (€ 205,296) had to be exports. Furthermore, to shed light on whether HGXs are not simply re-exporting products (Bernard et al., 2019; Damijan et al., 2013), we provide statistics on export-to-imports share to show that more than half of HGX do not import, and 25% of HGX export three times more than they import (Table OA6).

Monetary variables are log-transformed to address skewness. The dependent variable is a dummy indicating whether the firm is an HGX or not (= 0). We computed the linear probability model for three subsamples: HGXs vs HGfs, HGXs vs non-HGF exporters, and HGX vs non-HGF exporter with 5 or more employees.

The following linear probability model was estimated dependent on the reference group for HGX:

where the regression parameters/vectors are \({\beta }_{0},\cdots ,{\beta }_{14}\) and \(\varepsilon\) is the remainder noise. Variance inflation factors indicate no strong multicollinearity (Table OA10; GVIF < 4),Footnote 16 heteroscedastic robust standard errors are used.

Results in Table 3 show foreign ownership is associated with higher probability of being an HGX compared to HGfs and also compared to non-HGF exporters. Being export active in period t is associated with a higher probability of being an HGX compared to HGf. Since non-HGF exporters per definition have to be exporters in period t, but about 25% of HGXs are not exporters in period t, in the second model, there is actually a negative association having a non-HGF exporter or an HGX status due to the firm category definitions.

HGXs are associated with higher \(\frac{EBIT}{Total\; assets}\) and lower labor productivity compared to HGfs (Table 3). Compared to non-HGF exporters, HGXs are associated with higher average wage, younger age, but lower \(\frac{Book\; value\; of\; equity }{Total\; liabilities}\) and labor productivity. Regarding the latter, the literature on exporters (e.g., Melitz, 2003; Wagner, 2019) uses productivity as a key measure explaining why firms start exporting. As our results show, this does not hold for predicting HGX. HGXs are less productive than for example non-HGF exporters. Our further investigation shows that by the period t + 3, HGXs’ labor productivity triples on average which is probably due to learning-by-exporting (Atkin et al., 2017); however, more research is needed on this topic. Log R&D and log intangible assets are not statistically significantly associated with HGX status once controlling for sectors, firm size, and other firm characteristics. Relatedly, having a positive surplus is not different between HGX, HGfs and non-HGF exporters, nor is the quick ratioFootnote 17 or \(\frac{Retained\; earnings}{Total \;assets}\). Further investigations show that HGXs are less likely to exit compared to other HGfs or non-HGF exporters (Table OA11 – OA12).

We also run the model on the three subsamples (Table 3) by adding variables with higher bivariate correlations (r = 0.23 up to 0.67) stepwise into the regression. Either no collinearity issues (Table OA13-OA14) or not-at-all-severe collinearity issues (Table OA15) are present. We check robustness using three alternative HGX definitions, lower (40%) and higher (60%) minimum growth coming from exports as well as net export HGX definition (detailed definitions in the OA). We obtained similar results across alternative HGX definitions (Tables OA16 – OA19). The same model for the three subsamples as in Table 3 are run for period 2016–2019 which show quite similar results to Table 3 (Table OA20).

5.5 Product mix

Products are subject to customs regulation and are tracked in detail. For comparisons among firm categories, we focus on export-active firms in 2013, but allow changes in any direction in 2016. Table 4 shows several interesting results. In the category of HGXs, the number of export products grows rapidly, faster than for export-active HGfs. Although a smaller category of firms, HGXs start from a similar number of export products as HGfs (2628 vs 2864), but their growth is about twice that of HGfs (3001 vs 1470). The rapid growth of HGXs export products takes place while export superstars actually decrease the number of export products (from 5154 to 4697).

The non-HGF exporter category increases their number of export products per firm, but not as much as HGXs (0.6 vs 16.7 per firm). A total of 75% of HGXs increase the number of export products, which is a considerably higher percentage than in the other firm categories (export superstars = 32%; HGfs = 37%; non-HGF exporters = 27%). Clearly, HGXs are not just expanding the same products in new and/or existing markets, but are expanding the number of export products.

On average HGXs grow their number of export products, but to investigate the change in the distribution of the number of products, we examine the deciles of number of products across firm categories (Table 5). HGXs increase in number of products across all deciles, for example, at the 30% decile, HGXs grow from 3 to 7, at the median they grow from 6 to 11, while at 70th percentile they grow from 11 to 25 export products. As a robustness check, we also analyze the increase in export products when products are defined at the first 6-digit code of the CN8 code. Robustness results show similar patterns (although of course smaller in absolute values) for HGXs growth of export products (Table 19).Footnote 18 Thus, HGXs grow, and this growth is not just due to sales growth of the same products, but due to more export products, with different CN8 codes. The growth in number of export products is substantially different from other firm categories, for example, the first three deciles of HGfs do not export anymore, and they only increase in number of export products at the 80th and 90th percentiles. Similarly, non-HGF exporters and export superstars decrease in number of export products across all or the majority of deciles.

While HGXs grow in the number of export products, they might in addition explore new foreign markets. To examine this, we calculate the share of firms’ top export product in total export value (Table 6). More than 50% of HGXs have 75% or more exports from a single product; also, more than 70% of HGXs have 50% or more exports from a single product. Over the 3 years (i.e., 2013–2016), at the median, HGXs decrease in the share of top export product in total exports. At the 70th percentile, HGXs largest export product represents 95% of total exports, 3 years later, this share is 86%; at the median, HGXs had 76% in 2013, and 62% in 2016; and at the 30th percentile, HGXs decrease from 57 to 49%. At all deciles, the share of HGXs’ top export product decreases over time; however, at the 60th, 70th, 80th, and 90th deciles HGXs’ top product in 2016 is more than 70% of total exports. In contrast, export superstars have almost the same share of top export product in total exports over all deciles. HGfs and non-HGF exporters decrease in top export product share; however, this finding is driven by the first three percentiles where firms stop exporting by 2016.

Table 20 shows additional information for 2013–2016, including the number of export products, the number of new products and the number of dropped products. Results show that 60% of HGXs have at least 2 products growing from 2013 to 2016. Up to 30% of HGfs have at least 1 product growing in exports, and up to 40% of non-HGF exporters have at least 1 product growing in exports. After export superstars, HGXs have the second highest number of dropped products, for example, 70% of HGXs drop at least 1 product. As many as 80% of HGXs introduce 3 or more new products.

As the final firm-product analysis, we focus on the mean export product unit price (Table 7). In particular, we divide the export value for each export product and the number of units in which products are exported. We then calculate the mean unit price. In 2013, HGXs show a wide range of mean unit costs, from as little as € 12 at the 10th percentile, € 141 at the 30th percentile, € 631 at the median, € 10,736 at the 70th percentile up to as much as € 152,653 at the 90th percentile. By the end of the growth period (i.e., 2016), the mean unit prices increase to € 30 (10th percentile), € 202 (30th percentile), € 1719 (median), € 20,357 (70th percentile), and € 350,253 (90th percentile). On the other hand, HGfs and export superstars decrease in the mean unit prices across all deciles, while non-HGF exporters increase across all deciles. Comparing HGXs and non-HGF exporters, it seems that HGXs increase their unit prices substantially more. However, it should be clearly stated that the share of this increase in unit prices stems from introduction of new products by the HGXs (i.e., Table 4 and 5) which could have very different units, and therefore results in Table 7 are not necessarily strong evidence on quality upgrading, but could be a combination of both quality upgrading and introduction of new export products (Table 5, 19, OA21).

5.6 Export markets

This subsection analyzes whether HGXs growth is driven by more export products to the same markets or by diversifying export markets. Table 8 shows the number of firm-market observations across firm categories. HGXs are the only category of firms that have an increasing number of export markets. Their growth is impressive, the number of export markets in 2016 is almost twice the number of export markets they had in 2013. Between the 2013 and 2016, HGXs increase by 3.7 export markets on average. For HGfs, non-HGF exporters, and export superstars, the number of export markets decreases over the period 2013–2016.

Table 9 shows HGXs increase the number of export markets in all deciles from 2013 to 2016. By the end of the growth period (i.e., 2016), 50% of HGXs have more than 5 export markets. On the other hand, 30% of HGfs and non-HGF exporters stop exporting, and it seems that a majority decrease the number of export product-markets. At the upper deciles (70th, 80th, and 90th percentiles); however, some HGfs grow by increasing the export markets. Hence, HGfs display heterogeneity: some HGfs stop exporting, while other HGfs intensify their exporting by exporting more products and being active in more export markets.

Table 10 investigates whether HGXs grow by concentrating on their largest export market (Table 10). More than 80% of HGXs have 50% of their exports from a single export market in 2013, while about 60% of HGXs have 75% of their exports from a single export market. The share of exports in the largest export market decreases among HGXs over the growth period. In other words, HGXs growth leads to less reliance on any individual export market, because HGXs growth spreads out into a more diversified portfolio of export markets. Apart from the first decile, export superstars are decreasing their share of largest market in total exports; however, the changes are much smaller than among HGXs. HGfs decrease their reliance on the single largest export market; however, at the end of the growth period, the upper deciles (70th, 80th, and 90th percentile) focus their exports on a single export market (share of largest export market = 1). Finally, non-HGF exporters decrease their reliance on their top export market, but at a much smaller rate compared to HGXs.

Results in Table 11 show in 2013, 78% of HGXs export to the EU Single Market, while at the end of the growth period, as many as 90% export to the EU Single Market. HGXs also increase their presence in CEFTA markets (from 61 to 68%) and other export markets (from 39 to 51%). Interestingly, the only category of firms growing in the EU market is HGXs, HGXs can benefit from new business opportunities by offering competitive products.

In 2013, 57% of HGfs export to EU Single Market, 65% export to CEFTA, and 23% export to other markets. By the end of the growth period, HGfs decrease their presence in the EU Single Market (to 37%) but increase their presence in CEFTA (83%) and other markets (29%). Finally, Superstars remain present in the EU Single Market (97%) and other markets (78%) but decrease their presence in CEFTA markets (from 90 to 82%).

HGXs increase mean distance to the active export markets across all deciles except for the largest decile (Table 12). In 2013, 50% of HGXs have mean distance of 573 km; while in 2016, 50% of HGXs had a mean distance over 716 km. In 2013, about 70% of HGXs export to markets on average more than 850 km distant from Croatia, in 2016, 70% of HGXs have their mean distance to export market higher than 1150 km. Non-HGF exporters increase their mean distance in the majority of deciles, although some deciles (70th and 80th percentile) experience a decrease in mean distance. Export superstars increase their distance to export markets across all deciles, while exporters increase their distance in the mid and upper deciles.

The main finding is that HGXs are further away from their export markets than HGfs and non-HGF exporters, but not as much as export superstars.

6 Discussion

Previous literature on the economic contribution of exporters drew attention to large export superstars (Freund & Pierola, 2015, 2020). This study provides evidence for focusing also on the newly-defined category of high growth exporters (HGXs). While export superstars have achieved a large size, HGXs demonstrate growth. Awareness of HGXs may result in growth policies that (1) contrast the stability of export superstars’ workforce with HGX’s need for new employees, (2) ponder export superstars’ requirements in terms of the education level of their employees compared to the skill requirements of HGXs, and (3) consider the different relationships that export superstars and HGXs have with foreign markets. An exclusive focus on export superstars seems inappropriate, and an analysis considering both, export superstars and HGXs, enriches knowledge with respect to effective policy. While export superstars are important because of their current large size, in Croatia, they are declining in terms of total exports (Table 1), number of exported products (Table 4), and overall job creation (Table 2). Forward-looking and proactive policy should focus on HGXs, which may be the export superstars of tomorrow.

We began with a sectoral analysis of exporting activity. HGXs are present in various sectors, but are more prevalent in manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, and ICT. Tradeable sectors such as manufacturing are associated with R&D investment and productivity growth (Coad & Vezzani, 2019), highlighting the necessary policy interest in HGXs. Interestingly, there are no export superstars in the ICT sector in 2013, perhaps because the ICT sector is relatively young, and insufficient time has elapsed to allow promising ICT firms to grow into the export superstar category. Since there are no ICT firms in the export superstar category, we could look for leading ICT firms in the HGXs category, which (given that HGXs could become export superstars in the following periods) serve as promising candidates for tomorrow’s export superstars. Indeed, a first export superstar in ICT appears in 2016 (Table OA1) and finally an additional (second) export superstar in ICT in 2019.

6.1 HGXs and employment

We investigate the sources and characteristics of new HGXs employees. Do HGXs employees differ from HGfs, non-HGF exporters, and export superstars with respect to the new hires? During their growth episode, HGXs hire more employees from technology-intensive industries and employees with previous experience in exporting. HGXs are also observed to be more likely to hire on the basis of a single year work contract. In addition, HGXs are more likely to send new employees to work abroad. This is in line with the literature claiming the necessity of exporters to facilitate the connections to export markets (Srhoj et al., 2023). HGXs are particularly sensitive to information flows across countries and prefer to have employees abroad as a way of organizing their international operations. Therefore, HGXs can benefit from flexible labor markets and contracts that allow workers to move between firms, contributing with their knowledge to enable growth in export markets of firms and thus HGXs.

6.2 HGXs and their product offerings

HGXs substantially increase export value over the 3-year period. While HGXs grow in exports, their growth is not driven only by the top export product, because the share of the top export product in total exports substantially decreases (at the median from 76 to 62%). Instead, a robust finding is that HGXs increase in number of export products. Furthermore, growth in export products is not driven exclusively by new export products with incremental changes, but competitive products with higher unit prices that are sold in sophisticated export markets (such as the EU Single Market). In fact, a striking result is that the category that appears to benefit the most from new business opportunities (i.e., from the EU Single Market) by introducing new competitive products are HGXs.

HGXs’ growth involves diversification in involving export products with high unit prices. In addition, our findings suggest that HGXs are not the stereotypical cost-cutting entrants, but are able to competitively sell high-cost products in developed export markets such as the EU. Therefore, HGXs are not just expanding the same products in new markets, but expanding the number of markets and also the number of products at the same time.

The ability of HGXs to introduce sophisticated new export goods is reminiscent of Braguinsky et al. (2021) who observe that it is often the same firms that push forward their technological frontier with new products that also simultaneously push forward their sales growth in known technologies and familiar products. Thinking about our results regarding number of export products, we could make the distinction between incremental innovation and GPT (General Purpose Technology) innovation. The latter is probably associated with a new technology that leads to a swelling of product offerings in many different directions at the same time, whereas the former is probably more limited in terms of growth directions. In this case, the export growth of HGXs resembles the phenomenon of growing like yeast, whereby yeast makes bread grow evenly in many directions at the same time.

HGXs defy the trend observed for other groups of firms (e.g., HGfs, export superstars) that tend to prefer growth in closer export markets. HGXs are increasingly active in highly-developed EU markets rather than potentially less-developed export markets on poorer continents further afield. In contrast to HGXs, HGfs do not achieve growth in the large, rich, and developed EU market but in other markets. This suggests that the growth of HGfs may be less interesting than the growth of HGXs, in the eyes of policymakers. A similar pattern is observed for non-HGF exporters. Export superstars, for their part, are more globally competitive (presumably due to their previously-accumulated competitive advantage), although they are less dynamic than they used to be.

6.3 Policy interest in HGX

The impressive export performance of HGXs justifies policy interest in this category of firms. Note that the rapid growth of exports by HGXs is not merely a tautology, because (i) the HGX category refers to export growth, not export size, and (ii) if an export superstar also satisfies the HGX definition, it is categorized as an export superstar in our analysis.

Our results show the importance of HGXs and provide new knowledge on their micro-level characteristics. A first step in designing policy to support HGXs, even without having yet causal knowledge, is awareness and recognition of this category of firms, their relative frequencies, their growth patterns in terms of new products and markets, and their overall economic importance. By providing a first look into the HGX category, we intend to spur on policy discussions. A second step in designing policy to support HGXs relates to empirical evidence on the determinants and causes of HGXs performance. An important question is what policy-makers can do in the short-term and long-term to increase the probability of non-HGX firms becoming HGXs.

In the short run (1–2 years), a key question will be the ability to predict HGXs, and the ability of policy makers to nudge HGfs and non-HGF exporters (and perhaps even non-HGF domestic traders) to become HGXs, as well as supporting HGXs on the way to becoming export superstars. A monitoring system for policymakers could be established to better tailor a large set of existing short-term export boosting policies and initiatives to encourage exporting activity (for a review, see Srhoj et al., 2023). These policy initiatives to stimulate exporting activity include public grants, tax credits, subsidized export loans, export credit guarantees, public institutions offering partner search, matchmaking, intelligence, analysis and organizing participation on trade fairs, or providing vouchers for outgoing economic missions, fairs, and external counseling. There is also evidence for positive effects of demand-driven instruments, such as foreign market access programs (Atkin et al., 2017) or public procurement for innovation (Stojčić et al., 2020).

Medium-term (3–5 years) policy instruments could include R&D grants and changes to incentives via tax reform (Dimos et al., 2022). Large and smaller EU or US funded grants for innovation or technology upgrading have been shown to have a positive effect for those firms that apply (for a review: Dvouletý et al. 2021; for empirical studies: Santoleri et al., 2022; Howell, 2017).

In the long-term (5 + years), a standard innovation toolkit (Bloom et al., 2019) could assist in stimulating more HGXs. Firstly, countries could increase the supply of skilled labor, for example, by an immigration policy that targets highly skilled individuals and by improving the education system so that it develops the next generation of researchers and innovators. Secondly, since HGXs hire more on 1-year contracts, changes to labor markets in order to enable more flexible work contracts might be beneficial, although of course, more research is needed on this topic. Finally, developing the venture capital market could benefit the emergence and scaling-up of HGXs.

In short, policy recommendations for supporting HGX refer to addressing the liabilities of rapid growth. This contrasts with policy recommendations for Born Globals which often focus on addressing the liabilities of newness, e.g., addressing the low survival rates of newborns, and addressing their lack of reputation and/or experience, and/or lack of capabilities through training and knowledge development (Knight & Cavusgil, 2005, p. 32; Acedo & Jones, 2007, p. 248). Policy support for Born Globals may not be effective for achieving the intended policy targets, because many Born Globals have a disappointing performance in terms of growth of employment and sales (Ferguson et al., 2021).

7 Conclusion

Policymakers interested in job creation and economic development have shown a keen interest in high growth firms (HGFs; Grover et al., 2019; Benedetti Fasil et al., 2021) as well as export boosting (e.g., involving export superstars, Freund & Pierola, 2015, 2020; Srhoj et al., 2023). This paper presents evidence on a novel category of firms operating roughly at the intersection of these two groups, i.e., high growth exporters (HGXs), defined as a subgroup of revenue-based high growth firms with a substantial share of their growth (over 50%) coming from exports. We present a detailed analysis of HGXs, providing new insights at the level of region, sector, firm, firm-employee, firm-product, and firm-market. These dynamic and export-active firms have an impressive performance in a variety of areas, including entry into high unit-price product markets, entry into sophisticated export markets (such as the EU Single Market), and avoiding over-reliance on single products by engaging in growth through broad-based diversification. A limitation of our analysis is its focus on a single country, which is why we call for further research on the topic of HGX.

Notes

We highlight just those most relevant for our study. Interested readers can read all twelve facts in Mayer and Ottaviano (2008).

There may be fine distinctions between EIFs and Born Globals, for example, if EIFs are regional but not truly global (Sheppard and McNaughton, 2012). Such fine distinctions are beyond the scope of our present study.

Online Appendix (Figure OA1) gives the geographical position of Croatia in Europe.

Source: World Bank Data. Link: https://databank.worldbank.org/home.aspx [Accessed: 24th July 2022]. For indicator medium and high-tech exports (% manufactured exports), it is not possible to obtain world or OECD member state average.

There were inconsistencies in the variable exports. For example, a share of hotels reported their sales as exports because hotels are mostly used by foreign citizens (i.e., tourists). We examined such firms in a case-by-case manner, since this is not exporting in the definition of this study, we set the export values of firms in NACE 1-digit sectors Accommodation and food service activities and Administrative and support service activities to zero.

Several countries did not have bilateral distances, including Serbia, Kosovo, and Montenegro. We therefore constructed them ourselves based on the GeoDist website instructions.

This dataset includes firms, crafts, public institutions, and NGOs.

We use census dataset on all exporters to analyze export superstars in the Republic of Croatia with several definitions, the top 1, top 5, and the top 100 exporters by the absolute export value. Table 13 shows exports in total economy exports (%) of single, top 5, and top 100 exporters. Top 100 exporters account for 40–50% of total exports in the economy over the period 2013–2019. Table 14 gives descriptive statistics of Superstars, showing they have 730 employees, 167 million euro sales, and 82 million euro exports at the mean, with high mean market shares at 38%.

We would like to point out that at first the export superstars are categorized. Therefore, all firms in the category of HGX are not export superstars and thus HGXs may have the potential to become export superstars. From 2013 to 2016, there are 3 export superstars being also a high growth firm and having a growth in exports accounting for at least 50% of the sales growth; in the full sample with all years, out of 2534 HGXs 21 firms are export superstars fulfilling also the HGX criteria. However, this sequential classification step allows that each firm is categorized in a unique firm category.

Revenue-based HGFs are associated with higher aggregate productivity, which was not found for employee-based HGFs (Bisztray et al., 2023).

There are two consequences of not defining HGXs as simply HGFs that export in period t. Firstly, in the analyzed sample, this would lead to a 55% increase in the number of HGX, and secondly, 25% of actual HGXs would be dropped as they have no exports in period t.

Note that individual firms can be HGXs in more than one decade.

From 100 export superstars, nine export superstars are not active in 2016, with deeper case-by-case analysis showing these nine export superstars are merged or liquidated.

All other firms active in t and t + 3 that are not HGFs or export superstars.

The 90th percentile HGX sales were € 3,575,000 in 2013.

Tables OA7-OA9 and Figures OA2-OA4 in the Online-Appendix show correlation matrices of the independent variables for the three subsamples (HGX vs HGfs, HGX vs non-HGF exporters, and HGX vs non-HGF exporter with 5 or more employees).

Quick ratio is defined as cash/current liabilities (nonfinancial).

In addition, we also analyze first 4-digit code of the CN8 code (Table OA21). Main results do qualitatively not change.

References

Acedo, F. J., & Jones, M. V. (2007). Speed of internationalization and entrepreneurial cognition: Insights and a comparison between international new ventures, exporters and domestic firms. Journal of World Business, 42(3), 236–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2007.04.012

Albornoz, F., Pardo, H. F. C., Corcos, G., & Ornelas, E. (2012). Sequential exporting. Journal of International Economics, 88(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2012.02.007

Atkin, D., Khandelwal, A. K., & Osman, A. (2017). Exporting and firm performance: Evidence from a randomized experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2), 551–615. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx002

Bačić, K., & Aralica, Z. (2016). Innovation systems in Croatian regions. Društvena istraživanja: časopis za opća društvena pitanja, 25(2), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.5559/di.25.2.01

Baumgartner, C., Srhoj, S., & Walde, J. F. (2023). Harmonization of product classifications: A consistent time series of economic trade activities. Journal of Economics and Statistics, 243(6), 643–662. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2022-0034

Bell, J., McNaughton, R., & Young, S. (2001). ‘Born-again global’firms: An extension to the ‘born global’phenomenon. Journal of International Management, 7(3), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1075-4253(01)00043-6

Benedetti Fasil, C., Del Rio, J.C., Domnick, C., Fako, P., Flachenecker, F., Gavigan, J., Janiri, M., Stamenov, B., & Testa, G. (2021). High growth enterprises in the COVID-19 crisis context: Demographics, environmental innovations, digitalization, finance and policy measures (No. JRC124469). Joint Research Centre, Seville, Spain. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC124469

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., & Lawrence, R. Z. (1995). Exporters, jobs, and wages in US manufacturing: 1976–1987. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Microeconomics, 1995, 67–119. https://doi.org/10.2307/2534772

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2007). Firms in international trade. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.21.3.105

Bernard, A. B., Blanchard, E. J., Van Beveren, I., & Vandenbussche, H. (2019). Carry-along trade. The Review of Economic Studies, 86(2), 526–563. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdy006

Bisztray, M., De Nicola, F., & Muraközy, B. (2023). High-growth firms’ contribution to aggregate productivity growth. Small Business Economics, 60(2), 771–811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00614-9

Bloom, N., Van Reenen, J., & Williams, H. (2019). A toolkit of policies to promote innovation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(3), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.3.163