Abstract

Despite the rapid spread of equity crowdfunding, the role and actions played by entrepreneurial teams in this context have been neglected; the few studies in this field adopted a static view and focused primarily on their signaling role in equity crowdfunding campaigns, compared to solo founders. This study adopts a dynamic view and extends current literature by exploring the underlying dynamics and the role of entrepreneurial teams in the entire equity crowdfunding journey. Our findings reveal that entrepreneurial teams play a crucial role in three phases of equity crowdfunding, namely, the pre-campaign, during the campaign, and post-campaign phases. In the first phase, entrepreneurial teams are crucial in enhancing entrepreneurial alertness, social media use, social capital, entrepreneurial openness, and reducing the perceived uncertainty. The analysis shows that entrepreneurial teams are determinant for the success of the equity crowdfunding campaigns for human capital signals, certifications, social media use, and increased social capital and communication activities. Finally, the results highlight that entrepreneurial teams have valuable importance in the post-campaign phases in terms of crowd involvement/management, social capital and knowledge/network exploitation, improved resource mobilization, and resilience/robustness. Notably, social capital has a dynamic effect on equity crowdfunding activities over time. The results of this research have several implications for theory and for practice. We also discuss the implications of our findings for adopting a team approach, for small businesses undertaking the equity crowdfunding journey, and for other actors including platform managers and prospective investors.

Plain English Summary

The decision to found a new venture in a team has lasting effects for the entire life of the venture and implications for its survival, development, growth, and funding strategies. We examined entrepreneurial teams in the context of equity crowdfunding, a popular alternative market for young/small businesses that has recently grown exponentially. Prior research has taken a static view of the role of entrepreneurial teams in single phases of the equity crowdfunding journey and largely focused on their effects (on funding success) during the campaign. We conducted a qualitative research to explore in-depth the role and actions of the entrepreneurial team in the entire equity crowdfunding journey. Our research took into consideration the dynamic impact of entrepreneurial teams and highlighted their importance over time. Specifically, our findings provide novel insights on their involvement, contribution, and activities in each of the three phases, namely, pre-campaign, during the campaign, and post-campaign phases. The study highlights that entrepreneurial teams are crucial to increase venture openness and resource/opportunity recognition (pre-campaign phase), the probability of having successful equity crowdfunding campaigns, and better managing the post-campaign phase (including crowd engagement and knowledge/network exploitation). We find interesting implications for entrepreneurs who may consider a team approach to their ventures being a potential significant opportunity to increase the future benefits and cope with uncertain market scenarios, thus reducing possible negative impacts. Platform managers, investors, governments/regulators, and incubators/accelerators could take specific actions and programs considering the importance of entrepreneurial teams (e.g., promoting teams’ entrepreneurial decision-making, campaigns’ communication, and direct engagements).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Equity crowdfunding (ECF) has rapidly established itself as one of the main new players in the entrepreneurial finance landscape and a particularly popular external financial source for young entrepreneurial ventures (Block et al., 2018a; Brown et al., 2018; Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018a). It represents a specific crowdfunding model for small and new ventures (Vismara, 2016, 2018)—allowing them to make an open call through the Internet to sell a specified amount of equity shares to a large pool of crowd investors (Ahlers et al., 2015)—and a valuable alternative to traditional financing systems or professional investors (Piva & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018; Vismara, 2016).

In recent years, there has been a growing academic interest in ECF, and this acceleration is due to the strong diffusion and scale of the phenomenon (Cummings et al., 2020; Estrin et al., 2022; Ralcheva & Roosenboom, 2020). Research in this field has primarily and to a large extent explored the campaign phase, in particular by investigating the factors (or successful drivers) that increase the probability of campaign success on ECF platforms (Ahlers et al., 2015; Stevenson et al., 2019; Vismara, 2016). While these studies have focused on the investor decision-making process, only recently the exploration of the entrepreneur strategic fund-seeking decision-making process has caught the attention of some scholars aimed at shedding some light on the pre-campaign phase and especially the factors that drive entrepreneurs to search for ECF (Stevenson et al., 2022; Troise & Tani, 2021; Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018a). At the same time, several scholars have begun to question what happens to firms after ECF campaigns and therefore to shift attention towards the post-campaign phase (Coakley et al., 2022; Rossi et al., 2023; Signori & Vismara, 2018).

Despite the spread of these studies based on the different ECF phases, currently, there is a paucity of research specifically focused on entrepreneurial teams (ETs), and, in fact, scholars know very little about the possible roles and actions of ETs in the emerging ECF context. The only few studies on this topic have focused on the campaign phase—with a few exceptions on the post-campaign phase (Coakley et al., 2022; Hornuf et al., 2018; Rossi et al., 2023)—by exploring the impact of ETs’ presence and characteristics (such as size, education, and experiences), and the related signaling role, in influencing the success of ECF (Ahlers et al., 2015; Lim & Busenitz, 2020; Piva & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018; Troise et al., 2022a), especially disclosing the differences between “solo-founders” and ETs (Coakley et al., 2022). Although these few studies provided some initial evidence on the relationship between ETs and some ECF phases, they do not fully explore the importance and role of ETs in each phase and their collective dynamics. As argued by Brown et al. (2019), it is important not to overlook the fact that start-ups (and their entrepreneurs/ETs) move through the different phases of their equity crowdfunding “journey” (Brown et al., 2019), thus highlighting the need to consider all of them. In this sense, research still remain fragmented and focused on single phases and aspects of ETs. These studies have adopted a static view and do not take ET’s dynamic impact into consideration; in fact, they do not provide insights into the ET involvement and activities or actions they carry out before, during, and after the ECF campaign. These aspects have been neglected, and very little is still known about the contribution of ETs in the three phases of the ECF journey, namely, the pre-campaign, during the campaign, and the post-campaign phases. Hence, there is a need to advance current literature and shed some light on the importance of ETs and underlying dynamics that are aspects that still remain unclear, and it is remarkable that so little research in the ECF context has been provided in this direction.

This study aims to fill this gap in the current literature and analyzing ETs in depth and at different/multiple levels (Ye et al., 2023) by examining their roles and actions in the specific ECF context in the three different phases. While the topic has been the subject of considerable scholarly presumption, surprisingly, very little research has been conducted, also considering the exponential growth of research on ETs conducted over the years (Cooney, 2005; Schjoedt & Kraus, 2009), in particular, underlining that entrepreneurship is best accomplished by ETs (than by solo founders), their advantages (e.g., networks, skills, and resources) (Barringer et al., 2005), and positive influence on the performance of new ventures (Amason et al., 2006; Barringer et al., 2005; Florin et al., 2003; Foo et al., 2006).

To address the above-discussed gap, we conducted qualitative research. Specifically, this study uses a qualitative analysis, based on multiple case studies of ETs of 18 Italian ventures that have successfully used ECF and focused only on equity-crowdfunded ventures with an ET (and not those with solo-founders); we have integrated two main data sources: as primary data, we used semi-structured interviews conducted with ET members, while as secondary data, we used venture websites, reports, press, blogs, social media, and ECF platforms.

While earlier ECF research used a static view to explore whether ETs outperform solo-founders and their effects/roles in ECF phases (Ahlers et al., 2015; Piva & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018), this study instead makes a further step and leverages a dynamic view (Cai et al., 2021) to emphasize their importance and role over time, thus offering the perspective of the continuum (while the other studieslook only at discrete points in time).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: the next section provides a discussion of the literature, followed by the research design; the fourth section describes the main findings, while the fifth section provides a discussion of these findings; the last section concludes the paper.

2 Literature review

2.1 ECF and the phases

Over the last decade, ECF has become a valuable alternative market for entrepreneurs seeking external financing for their firms and for small investors who intend to engage in financing these firms (Rossi et al., 2023). This market has seen a particularly rapid growth in the last few years (Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance, 2021; Vismara, 2022), and a growing number of regulators have started to realize its economic potential, especially in response to financial crisis, and consequently to introduce specific regulations and legalize it (Hornuf & Schwienbacher, 2017; Stevenson et al., 2022; Vismara, 2016). At the same time, also the literature on ECF has also grown exponentially in the last few years, although it is still fragmented and sparse (Mochkabadi & Volkmann, 2020; Stevenson et al., 2022).

Initial studies in the field of ECF have primarily explored the funding dynamics during ECF campaigns (Hornuf & Schwienbacher, 2018; Vismara, 2018) and the factors that lead to the success of these campaigns—with several scholars leveraging the signaling theory (Ahlers et al., 2015; Butticè et al., 2022; Piva & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018; Vismara, 2016); therefore, these studies have largely focused on investor decision-making processes to improve the collective understanding of the behaviors of investors engaging in ECF. Among the success drivers of ECF campaigns identified by the literature are updates during the campaigns (Block et al., 2018b), equity retention (Ahlers et al., 2015; Vismara, 2016), geography (Cumming et al., 2021; Guenther et al., 2018), detailed disclosure of qualitative business information (Johan & Zhang, 2020), crowd cues (i.e., investment opportunities’ indicators) (Stevenson et al., 2019), risk information (Ahlers et al., 2015), involvement of professional investors (Vismara, 2018), human capital (Ahlers et al., 2015; Piva & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018; Troise et al., 2022a), founders’ relationships, and social networks (or capital) (Lukkarinen et al., 2016; Polzin et al., 2018; Troise et al., 2020, 2022a; Vismara, 2016). Regarding the latter, social capital theory represents a lens frequently adopted in ECF research, and is particularly suitable as it fits into the nature of ECF in which entrepreneurs seek financial resources from a large pool of people (Cai et al., 2021). Through social capital, scholars have explained the success of ECF campaigns but have also demonstrated that it represents a crucial antecedent of the outcomes of these campaigns given the role of entrepreneurs’ social capital in raising financial resources from their private networks during a “hidden” phase before the campaign is publicly opened, which in turn increases the probability of successfully ECF campaigns (Brown et al., 2019; Lukkarinen et al., 2016). However, as noted by Cai et al. (2021), very little attention has been paid to the effects of social capital in the post-ECF phase.

Over the years, the literature has been rooted mainly in the study of the campaign phase; however, recently, several studies have begun to focus on two other phases worthy of further and in-depth investigations and about which very little was known, namely, the pre-campaign phase and the post-campaign phase.

Regarding the first, one of the less investigated topics in the ECF literature, some pioneering scholars have highlighted the need to integrate previous research on investor decision-making with new specific research focused on entrepreneur fund-seeking (Stevenson et al., 2022; Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018a) and therefore the importance of shedding light on the motivations or factors leading entrepreneurs to use ECF generally (Brown et al., 2018). Little is known, in fact, of what drives firms to search for ECF and prefer it over other equity forms of financing, a topic that has so far been neglected. In this vein, Stevenson et al., (2022, p.2062) reported that the approach based on investor decision-making “while valuable, de-emphasizes the antecedent role of the entrepreneur who must first decide which equity sources to seek and initiate the fund-seeking process itself.” In this vein, an increasing number of scholars have become interested in studying the antecedents of ECF fund-seeking and the entrepreneur decision-making (Blaseg et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2018; Troise & Tani, 2021; Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018a). The first studies in this sense have provided evidence that ECF is not a primary source of external financing but an option of “last resort” for firms, especially in case of financial constraints such as lack of internal funds or additional debt capacity (Brown et al., 2018; Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018a). Among these initial studies, Walthoff-Borm et al. (2018a) used the pecking order theory and showed that—compared to firms not listed on ECF platforms—firms listed on these ECF platforms are less profitable, have more intangible assets, and more often have excessive debt levels. Similarly, other scholars found that ECF represents a secondary option for entrepreneurs (Blaseg et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2018); this is especially true for low-quality entrepreneurs tied to more risky banks (Blaseg et al., 2021) or the experimental/improvisational entrepreneurs of young innovative ventures seeking quick financing, defined by Brown et al. (2018) (leveraging the entrepreneurial bricolage perspective) as the “discouraged borrowers.” In contrast with this perspective, recent studies support the idea that ECF may represent a preferred financing option rather than a last resort (Cummings et al., 2020; Stevenson et al., 2022). In this sense, Stevenson et al. (2022), through a dynamic contingency-based model, highlighted that ECF represents a strategic option for entrepreneurs, who are motivated by the perceived funding fit and hence the best choice to satisfy their specific needs. Similarly, Estrin et al. (2018) described the entrepreneurs’ reasons for adopting ECF, thus bypassing institutional funding models such as banks, Venture Capitalists (VCs) or Business Angels (BAs), reporting among others that entrepreneurs use ECF to satisfy some needs such as having a quick access to a large crowd of investors and their networks. In a similar vein, other recent studies explored the entrepreneurs’ motivation for pursuing ECF bypassing traditional funding models in the context of university spin-offs (Troise et al., 2023b) or to internationalize (Troise et al., 2023a). Finally, towards the goal of exploring the entrepreneurial decision-making in ECF, Troise and Tani (2021) demonstrated the strategic role of ECF for entrepreneurs seeking for additional resources (such as promotion, knowledge, and networking) beyond funding and the existing connections between entrepreneurial characteristics, motivation (to adopt ECF), and behaviors.

Regarding the second phase, namely, the post-campaign phase, it is still a research stream in its infancy and a field not fully explored, although existing studies have made considerable progress in improving the current understanding in this sense. Only recently, in fact, scholars have begun to wonder about what happens after successful or unsuccessful ECF campaigns and to focus on the post-campaign outcomes (Rossi et al., 2023; Signori & Vismara, 2018; Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018b). The early studies analyzed the impacts of successful ECF offering on new venture performance, survival, innovation, and follow-up funding (Butticè et al., 2020; Coakley et al., 2022; Eldridge et al., 2021; Hornuf et al., 2018; Signori & Vismara, 2018; Troise et al., 2021, 2023a; Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018b), with the idea that the ultimate goal of pursuing ECF is to build enduring businesses (Signori & Vismara, 2018). Some of these studies explored ECF campaigns’ factors influencing the post-campaign phases (e.g., Signori & Vismara, 2018), while others compared equity-crowdfunded ventures with those not funded through ECF (but other systems) (e.g., Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018b). The first study in this emerging research stream of studies on the post-campaign phase was the research of Signori and Vismara (2018) disclosing several predictors (e.g., the presence of non-executive directors, patents, positive sales, and qualified investors). Hornuf et al. (2018) showed that ventures successfully funded through ECF, although less likely to survive, they are more likely to receive follow-up funding through VCs or BAs. Similarly, Walthoff-Borm et al. (2018b) have found a high probability of failure for firms that have successfully raised funds through ECF campaign compared to those that have not used ECF, although the equity-crowdfunded firms outperform the non-equity crowdfunded ones in terms of innovation performance (specifically in patenting applications). The study of Eldridge et al. (2021) provided evidence that ECF positively influences the growth opportunity of SMEs but not innovation performance. Troise et al. (2021) also explored the post-campaign by investigating the innovation outcomes of equity-crowdfunded firms and highlighting the crucial role of knowledge-based crowd inputs in supporting firms in pursuing sustainability-oriented innovations (SOIs). Despite the various reasonsFootnote 1 that make the study of financing sustainability-oriented companies of particular interest (Vismara, 2019) and the related post-campaign outcomes (Troise et al., 2021), surprisingly, the exploration of the relationships between ECF and sustainability has received less attention in the literature as underlined by the first research in this specific area conducted by Vismara (2019) which demonstrated that sustainability orientation attracts a greater number of restricted investors (i.e., the crowd) but not of professional investors and does not influence the probability of success of ECF campaigns.

Other studies have focused on the additional resources and intangible benefits of ECF—as well as the effects of crowd engagement on new ventures’ developments—in particular in terms of network and knowledge exploitation (such as access to network, raise awareness, acquire knowledge on strategy or market, product validation/testing, brand development, and promotion improvements) (Brown et al., 2018; Di Pietro et al., 2018; Estrin et al., 2018; Troise et al., 2023a, 2023b). While these studies have explored the post-campaign phase of firms that had successful ECF campaigns, studies that have explored what happens after unsuccessful ECF campaigns remain extremely limited and in their infancy, with the only two exceptions being the studies of Walthoff-Borm et al. (2018a)—highlighting the considerable failure rate (around 40%) in the short term of firms that have had unsuccessful ECF campaigns—and Rossi et al. (2023) focused on family business start-ups. The latter represents a recent and valuable contribution to this emerging literature showing that these specific firms are more likely to offer shares with voting rights after an unsuccessful campaign, and they are more likely to raise equity financing compared to non-family business start-ups.

2.2 ETs in the ECF

Despite recent advances in the literature on the ECF phases, the study of ETs—which in the case of new ventures, i.e., the target of ECF system, constitute the management team (Hornuf et al., 2018) or overlap the owners (Rossi et al., 2023)—remains fragmented and mainly limited to the campaign phase. In particular, scholars have explored if the presence of ETs and their characteristics have some effects on ECF campaign outcome (Ahlers et al., 2015; Coakley et al., 2022; Lim & Busenitz, 2020; Lukkarinen et al., 2016; Piva & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018; Troise et al., 2020, 2022a). Most of these scholars have considered the human capital perspective to explain the impact of ET characteristics on the success or failure of ECF campaigns (Ahlers et al., 2015; Coakley et al., 2022; Piva & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018; Troise et al., 2022a). Scholars have primarily examined if the presence of ETs increases the chance of success (or failure) of the ECF campaigns (e.g., Coakley et al., 2022, which measured the presence of solo-founders or ETs with a dummy variable) and takes into account characteristics of the team such as the size (Ahlers et al., 2015; Vismara, 2018), education (Ahlers et al., 2015; Barbi & Mattioli, 2019; Coakley et al., 2022; Lukkarinen et al., 2016; Piva & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018), gender (Barbi & Mattioli, 2019; Cumming et al., 2021; Prokop & Wang, 2022), prior experiences (especially professional and entrepreneurial ones) (Barbi & Mattioli, 2019; Coakley et al., 2022; Lukkarinen et al., 2016; Piva & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018; Troise et al., 2022a), age (Coakley et al., 2022; Cumming et al., 2021), and geography and ethnicity (Cumming et al., 2021). In this vein, Lim and Busenitz (2020) highlighted that ETs are more highly valued than solo-founders by prospective investors in ECF, as well as these ETs compensate for lack of experience and reduce potential negative effects (compared to solo-founders). In a similar vein, the study of Vismara (2019) focusing on sustainability in ECF showed the importance of ET size in increasing outside investors’ perception of businesses’ ability to cope and navigate uncertain market scenarios.

At the same time, there are a limited number of studies in the literature that represent exceptions and have explored the effects of ET in the post-campaign phase. The study of Hornuf et al. (2018) demonstrated that larger ETs have positive effects on firms’ follow‐up funding, thus highlighting the increasing likelihood of receiving further funding from VCs and BAs after ECF campaigns. In a similar vein, Coakley et al. (2022) showed that ETs perform better than solo-founders in terms of ECF campaign success and survival rate of crowdfunded ventures; specifically, their study provided evidence that ETs are not only more likely to succeed in ECF campaigns and raise more capital than solo-founders but also that they are less likely to fail after ECF campaigns. The study of Rossi et al. (2023) explored the role of ETs in relation to family businesses and shed light on their responses to the negative ECF campaign outcomes, i.e., the unsuccessful campaigns; they found that these ventures have higher probability of raising new equity financing after these ECF campaigns’ failures.

Apart from these studies, however, we are unaware of any research in the current literature on the role of ETs in the pre-campaign phase. The latter, in fact, unlike the other two phases, is still unexplored although the ETs’ perspective and behaviors before the use of ECF (and the launch of the campaign) represent intriguing opportunities for research, especially given the importance of entrepreneurial characteristics and motivations in determining the ECF campaigns’ strategies (Troise & Tani, 2021).

The sporadic studies of ETs previously discussed have provided some initial evidence on the relationship between ETs and the phases of ECF; however, they did not address the question of what the contribution, involvement, or activities/actions of ETs are in the three phases of ECF. The role of ETs played towards the phases of the ECF journey seems not yet fully explored, with a significant gap in the pre-campaign phase where we do not have studies on ETs. While we have some evidence from the literature of the effects of ETs' presence and characteristics on the success of ECF campaigns and the follow‐up funding or survival of equity-crowdfunded ventures, we have no knowledge of the contribution of ETs in these phases and their role in each of them. Distinct from prior research, we focus on the role of ETs in the three phases of ECF and unpack their contributions and activities/actions. In this sense, we have a unique opportunity to investigate how ETs have different roles and effects in the three ECF phases. This study tries to shed some light on the dynamic impact of ET on the ECF phases, and provides an in-depth analysis of its role during the ECF journey, thus providing a contribution in expanding the current literature mainly based on a static view and on the study of the campaign phase with a few exceptions on the post-campaign phase.

Finally, the exponential spread of ECF and its uniqueness (Stevenson et al., 2022; Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018a) has driven an increasing number of scholars to call for more studies to examine in-depth decisions or motivation of different types of ECF fund-seekers (e.g., Cummings et al., 2020; Stevenson et al., 2022; Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018a;) and the role of entrepreneurs in the post-campaign phase by exploring different scenarios (including the case of unsuccessful ECF campaigns) (e.g. Rossi et al., 2023). At the same time, recent studies call for further research to investigate ECF at different or multiple levels and to advance current understanding of the role of ETs (e.g., Coakley et al., 2022). With this study, we tried to answer these calls and advance current literature, improving our understanding of the strategic role of ETs in all the ECF phase.

3 Research design

This research focuses on ETs in ECF, a recent phenomenon as defined by scholars (Estrin et al., 2018). To depict the role and relationships between the ETs and ECF context, we adopted a qualitative approach based on a multiple case method (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). Specifically, we investigated 18 Italian ventures—small businesses—and examined the views and activities of their ET members involved in the ECF context. We decided to focus on the Italian ECF market because it is a vibrant country in the field of ECF; in fact, Italy was the first country in Europe to regulate ECF with a specific law and the ConsobFootnote 2 authority provided a register for ECF platforms, thus allowing the use of a cross-platform (Troise et al., 2021, 2022a). Furthermore, Italy is characterized by the presence of small businesses, and the governments pay particular attention to introducing regulations to encourage the rise/development of innovative start-ups and the related use of ECF.

Purposive sampling technique was used to choose the participants (Patton, 2002). This specific technique is used to identify the information-rich cases of ETs in ECF and the well-informed founders of the phenomenon. In our case, we focused only on ventures that have successfully raised funds through ECF campaigns (i.e., crowdfunded ventures) and only on ventures with ETs,Footnote 3 thus excluding the ventures with solo founders. Currently, there is a general consensus in the literature that an ET is composed of a group of people—two or more individuals (Cooney, 2005)—who exhibit at least two of the following three characteristics (Ensley & Hmieleski, 2005): (1) to be a founder, that is, to have that specific status; (2) to have significant equity stakes, that is to be significant stakeholders (i.e., 10% or more); (3) to be actively involved in the strategic decision-making for the new firm. In line with these characteristics recognized by the literature, ETs possess at least two of the conditions described above.

We had good knowledge of the ventures composed by ETs that have adopted ECF and we departed from these ventures that we already knew from previous studies. We conducted two initial pilot interviews to ensure the clarity of the question, the understanding of the participants, and the logical flow.

The final number of ventures included in the study was 18, and for each, we interviewed at least half of the ET members. Data collection lasted about six months between December 2021 and May 2022, and the sources are reported in Table 1. We conducted a second round of interviews in the period March–May 2023, to complete our research findings and get a deeper understanding about some crucial elements that emerged during the first round of interviews (such as further investigate the decision to fundraise through ECF, the consideration and engagement of early investors, and the ETs role across the ECF phases). Table 2, instead, provides a description of the sample characteristics.

This study adopted the “Gioia Method,” a well-known methodology to enhance the qualitative rigor of the research (Gioia et al., 2013). The interviews were transcribed, and their analysis led to the codification of the main and emerging concepts concerning the roles of ETs in three different phases of ECF and the underlying dynamics. The interview protocol was almost standardized across interviews. First, we asked the ET members to illustrate venture characteristics, developments, and challenges they faced; then, we focused on the roles and actions of ETs in the ECF journey. The latter includes the overall phases (i.e., the entire process) of ECF and the related performance, thus allowing us to get relevant details on different phases and not only information about the campaign’s performance.

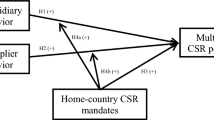

Primary data allowed us to identify the main points, followed by the definition of common themes; the last step was the assignment of final categories (Punch, 2005). In sum, the process was as follows: first, we derived first-order concepts, then the second-order ones, and finally the aggregate dimensions. Data structure is reported in Fig. 1.

4 Findings

The interviews ultimately revealed valuable information on the role of ETs in three different phases, namely, the pre-campaign, during the campaign, and post-campaign phase, as detailed in the following sub-sections. In these, we discuss the major findings of our study according to each phase of the ECF journey.

4.1 ET role: ECF pre-campaign phase

The interviews reported significant details on the actions and role of ETs in the pre-campaign phase, i.e., before the launch of the ECF campaign. Their actions ultimately influence the strategic decision of the venture to use this new system and fuel the entrepreneurial decision-making process.

Many interviewees declared that ET plays a key role in the entrepreneurial action of identifying valuable opportunities and useful resources for the venture. ET members, in fact, are involved in a proactive activity of searching for information and identifying the best opportunities to support the development and growth of their ventures. In particular, ET reveals a high ability to connect information and establish relationships with different domains, sometimes unrelated to each other.

One of the interviewees highlighted that the venture was founded as a result of action and the presence of such a team, in the specific case a team of 4 founders, was fundamental to identifying the best opportunities for it, particularly in the use of ECF. Specifically, he stated “our start-up was founded by 4 members and all of us are particularly active in the search for new information useful to further develop and growth our firm; in particular all the team seek information to raise funds and new tools to support our start-up; our collective research efforts have led us to identify equity crowdfunding, an alternative financing instrument that also represents in a certain sense a gamble given its recent appearance.” Similarly, another interviewee pointed out that the ET helped the venture to increase the frequency of interactions with other stakeholders, thus multiplying the possibilities of acquiring new information and above all acquiring the most relevant information for the venture. Most of the interviewees underlined that the action of the ET is crucial for evaluating the opportunities and connections of the information gathered. In this sense, one founder said “without the commitment of the entire entrepreneurial team, it would not have been possible to carry out a targeted assessment of the individual opportunities identified; this led to the identification of a series of strategic choices including the use of equity crowdfunding; moreover, it should be noted that together we were able to complete the ‘puzzle’ of the numerous information collected and identify the missing piece for our first phase of development, that is in our case a small amount of resources to complete the development of our application and test it immediately on the market with an initial distribution of the service at national level; put simply, we needed funds but also useful feedback to test the market.” Similarly, another founder pointed out that “we consider crowd investors as a potential new source for our business, not only in terms of funding; the decision to take advantage of an equity crowdfunding mechanism was made by all team members after we identified some interesting potential returns, also of a non-financial nature.”

Apart from the higher level of alertness, it emerges from the interviews that the ET actions allowed them to reduce their perceived uncertainty related to the novelty of the entrepreneurial initiative and the surrounding environment. The changing environment influences the decision-making process of all entrepreneurs and their judgments especially related to the mobilization of financial resources. Several interviewees pointed out that the presence of an ET—and consequently their actions—represented a point of strength for their ventures given the high levels of uncertainty related to the volatility of the market and the changes in both the market and industry in general. In this sense, an ET member said “we founded a new venture in a vibrant and rapidly changing sector, namely eco-friendly products, strictly related to the green economy and in particular the recent international goals of sustainability and the circular economy; at the beginning, we were among the first players in the sector, we believed that the best way to address the uncertainty related to the sector was to take collective action, combining our strengths and skills to try to give light to our business idea. This was a winning solution, and thanks to our collective judgments, we decided to approach the equity crowdfunding system.” In a similar way, another founder said “in our case, the entrepreneurial team was fundamental to engage an entrepreneurial behavior, that is the creation of a new venture; we established an innovative start-up, and after one year from the establishment, we launched an important equity crowdfunding campaign and offered a large part of equity shares [over 10%]; honestly, alone I would not have created the venture around the business idea and above all I would not have launched a crowdfunding campaign, not even knowing its existence […].” On the same topic, a founder reported that “personally I have always seen the creation of a start-up and the search for financial resources as very uncertain activities, however I must emphasize that the entrepreneurial team has certainly made it possible to seize the opportunities of the market, despite the uncertainty of the European context and the service sector, and it has certainly provided all of us with a greater capacity to bear the felt uncertainty; as a consequence, we decided to act and use an equity crowdfunding platform to raise funds.”

All the interviewees emphasized that ETs use social media more efficiently and massively. ET members adopt proactively several social media for different purposes, especially to access to information and establish and manage relationships with other actors and for marketing purposes. Founders reveal that through social media, the ETs monitor the market and can take specific actions. Among them, the use of social media by ET members helps to create relationships with third-parties, in particular, other relevant stakeholders for the venture (e.g., customers, other ventures, and industrial partners). At the same time, the ET actions in terms of social media uses have allowed the venture to attract new investors and access greater financial resources as well as new fundraising systems. A founder, for example, spoke about the “actions by the whole entrepreneurial team of the exploitation of social media to increase relationships and find new investors for the venture,” while another one talked about the proactive social media use thanks to the team members (in the specific case 3 founders) which leverage social media—especially LinkedIn, Instagram, and Facebook—to access market information and financial ones; the founder underlined that “thanks to our active ET using social media, we have navigated the uncertain scenario typical of entrepreneurial finance, and increase the opportunities to access to new financial resources; without the proactive use by all ET members, we would not have been able to meet new players in the arena, such as (equity) crowdfunding which has appeared recently and only through dedicated online platforms.” Advances in social media and online platforms require more engagement from firms, and the ET interviewed highlighted their higher propensity to use social media for key purposes for the venture. A very interesting aspect that has emerged from the interviews with ET members is that their use of social media and (also) the network ties were crucial in the “early stage” of the crowdfunding journey and, hence, before the launch of a campaign, including—eventually—a preparation stage. In this phase, often defined in general terms in crowdfunding contexts as the “friend-funding” stage, the presence of an ET guarantees a higher level of key resources (compared to solo founders) such as networks and social capital. ETs’ direct connections, in fact, played a key role in engaging investors not only from family, friends, and fans but also from other amateur investors through social media and other online channels. A founder stated that “we all team members brought our contacts, including family, friends, partners and other potential interested parties; the presence of a team was very important, allowing us to amplify the effects and generate hype.” Direct and close social connections of ETs are essential during the preparation period of an ECF campaign and, at the same time, ET communication efforts—especially in terms of posts, videos, blogs, etc.—were useful to spread the future launch of the campaign and to increase the attention of people, with the aim to influence a good number of early investors/backers. To support this, a founder reported that “both our direct contacts of various kinds, and the activities of communication, such as posts on social media and online pitches, have played an important role in influencing some early investors before the launch of the campaign, raising awareness in advance.” It is interesting to note that the interviews highlighted a non-negligible advantage deriving from the private networks of ETs, that is the possibility to attract financial resources during the so-called “hidden stage” of the campaign. The latter refers to a pre-campaign phase where founders can invite private network members or partners and suggest them to invest in their initiative, thus offering them the opportunity to be among the first investors. To support this, a founder explained that this phase provided a unique and valuable opportunity to engage not only initial amateur investors in the personal sphere of the ETs but also key partners and, potentially, lead investors by invitation. Furthermore, another founder highlighted that in the Italian ECF context, the presence of professional investors is required by law and campaigns must raise at list 5% of the capital from accredited investors; in this case, the contacts of ETs with specific targeted investors are particularly relevant.

Finally, the interviews provided indications that an ET plays a crucial role in increasing the level of entrepreneurial openness of the team and ultimately in overcoming a potential—initial—lack of openness. ET members suggested that their openness is greater thanks to the collective vision of the team; in this sense, a founder reported that “perhaps, our visions in an isolated way would have been limiting for society, probably not all with a high degree of openness towards the outside and in general towards the news […].” To support this argument, another founder declared that “our venture is a small and young firm, our openness is high, and I think it is due to a sort of ‘collective opening’ of the entrepreneurial team, because we have collectively decided to be more open and increase the opportunities for our venture; we are in close contact and try our best to share experiences, knowledge and networks; honestly, without the openness of our whole team, I'm usually not a very open person,” one of his co-founders in this sense stated that openness is a “collective effort and the different levels of openness of individuals are compensated for, as now you are a single team operating and going in the same direction.”

Several founders discussed the importance of ET openness to learn different new approaches, which in turn improved the venture’s capabilities and knowledge. Some examples, provided by ET members, are related to learning new approaches to the market or marketing activities and, above all, to the ability to learn from previous success stories that have been assimilated and shared. Two founders of the same ET, in fact, pointed out that they are passionate readers of articles published in magazines and blogs dedicated to successful entrepreneurs and are fans of a multitude of entrepreneurship programs (such as B Heroes and Shark Thank) that they follow constantly.

This level of openness is also related to the dimensions of novelties and feedback. Most of the ET members reported that they constantly look for useful news for their business, such as the possibility of collaborating with other ventures, improving the services, and entering new markets. A founder said “all of us team members try to find new ideas or feedback to improve our current services and develop new ones according to the needs of consumers, we are always open to their comments.” Similarly, another founder discussed opportunities in foreign markets thanks to information obtained from outside. Notably, most ET members pointed out that the opportunity to use ECF came from the information received from the outside and ET’s great openness to news, especially the previous viewing of other successful campaigns of ECF and the consequent development of ventures after the campaigns.

4.2 ET role: ECF during the campaign phase

The interviewees offered various reasons for the crucial importance of the ET during the crowdfunding campaign, useful for ensuring its ultimate success.

All the founders interviewed reported that the presence of an ET represented a successful driver of the ECF campaigns. The ET members highlighted that a team made up of various founders with different experiences and skills represented an added value and a strength for the venture and its financing campaign. In fact, a larger and more heterogeneous team represents a credible signal for external investors about the quality of the venture. Most of the ventures posted specific details, updates, and links to disclose information on their previous experiences and, in general, on “who they are.” According to a founder, “investors have paid close attention to our backgrounds, skills and professional or work experiences; in fact, some have asked us to send them our CVs and links to our profiles where our previous work experiences are highlighted, such as LinkedIn.” Based on the success of their campaigns and the comments of many investors or the interactions (pre- and post- campaign) between founders and investors, ET members stressed that the size of ET was critical for investors to decide to commit financial resources, and—at the same time—the education level of the members was highly relevant for influencing collective investment decision-making. Interestingly, an ET member revealed that one of the most important aspects of the investors’ judgments was the previous entrepreneurial or start-up experience of the team members. Specifically, he said “most of the investors were small amateur investors, and many of them asked my team colleagues and me to describe our previous experiences in other start-ups and entrepreneurial projects; it was important for them to have information about our ‘knowledge’ on the entrepreneurial process and—according to many of them—this was valuable in stating that, in a sense, we have enough experience to solve potential problems or avoid / prevent mistakes.” Other ET members described work experiences and industry knowledge as useful elements for investors to consider and able to change the trajectories of ECF campaigns (i.e., influence their success of failure).

The ET members’ qualities and characteristics have a signaling effect on crowd investors; however, their communication activities also influence the success of ECF campaigns. As described above, founders provided and posted several types of info to improve investor knowledge. However, ET members do much more during campaigns to increase the chances of them investing funds In fact, they play a very active role in managing conversations with investors and in providing constant updates as well as the use of multiple (interactive) communication tools. According to an ET member, the investors were very happy that the ET provided timely responses to their comments and posted specific updates during the campaign useful for the investors; this ET member said “the responses of all ET members were greatly appreciated by our investors, they saw that the team is united, compact, and we are all ready to work with future investors to improve our business venture and to have, hopefully, success in the future.” Other ET members emphasized the great entrepreneurial teamwork in producing a significant amount of content suitable for multiple types of interlocutors. Most of the interviewees showed specific videos made by the whole ET to describe the entrepreneurial initiatives together. Many campaigns proposed videos that include presentations from each individual ET members. Based on the comments of some founders, this active participation of the ET significantly improved the online narrative, thus encouraging a large number of crowd investors to support the campaigns.

The presence of an ET has a valuable benefit for entrepreneurial initiatives posted on ECF platforms in terms of increased social network ties and interactions. The ET members play an active role in mobilizing their network and promoting the ECF campaign through their friends and followers on the main social media, such as Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram. The vast majority of the interviewees pointed out that the presence of a high number of social media connections of each ET member was crucial for the success of the campaigns. A founder declared that “thanks to the number of Facebook and LinkedIn connections of our entrepreneurial team members, we had the opportunity to spread our message exponentially and directly involve many of our friends, relatives and acquaintances.” Similarly, another founder reported that “without our entrepreneurial team we would not have been able to expand our network so quickly and have an imminent impact on fundraising.”

Interestingly, some founders support and share the idea that social connections are useful especially at the start of the ECF campaign to attract early investors and, consequently, to increase its chance of success. In this initial phase, in fact, they affirmed that was determinant for the later success to engage a large number of investors from all the potential connections and networks, i.e., not only the well-known “3F” but also other users/investors with several online channels or that populated the platforms. A founder reported that “our initial efforts were helpful at the start of the equity crowdfunding campaign as they allowed us to reach a high level of our initial funding goal after a very short period of time; these efforts proved to be successful as we reached the target long before the end of the campaign, and it allowed us to have a rich overfunding rate far exceeding the initial target; in our case, I would say that the (entrepreneurial) founding team has been determinant in maximizing the initial efforts and that the early investors involved have been a driving force for subsequent investors.” On more than one occasion, the founders have argued that some investors had direct connections with ET members and this represented a non-negligible motivation to support a specific initiative with the aim of maintaining and strengthening existing relationships. At the same time, the communication efforts made by the ETs have been useful not only in engaging direct contacts but also in increasing the participation of new investors/backers and convincing “strangers” to commit financial resources, especially thanks to the simpler language used by the ETs in their updates and the large amount of information they provided on the initiative to enhance trust in them. The opportunity to build new networks has been seized by several founders who have actively maintained interactions with new investors through the dedicated spaces within the online platforms and on the main social media. A founder stated “I and the other two members of the team paid close attention to the new investors trying to establish a connection with them and building some kind of trust, since it was actually an investment in a startup that could seem risky; we believe that this interaction activity must be done and is also useful for the future of our venture.” Other founders have argued that both existing contacts and new ones from new backers/investors trigger a useful word-of-mouth (WoM) effect.

Finally, the ET members interviewed highlighted the importance of certifications in the context of ECF campaigns. Specifically, a number of founders reported that the presence of an ET had a certification effect for the venture on the ECF campaign, as this parameter can influence the investment decisions of both amateur and professional investors during the campaign. In this vein, a founder suggested that “as many investors have told me, our team played a key role in reducing their uncertainty about investing in a new venture.” Another interesting aspect that emerged from the interviews was the importance of external certifications to increase the likelihood of investors to finance the project. In this sense, ET members who disseminate information on the awards won (both at individual and venture level), participate in important events, and obtain visibility from reliable sources (e.g., specific press and expert opinions) have shown higher performance during their campaigns. A founder, for example, stated that “our start-up won an award related to sustainability, while one of our entrepreneurial team members won a scientific award; both of these awards have attracted investors and have shown them that the venture is worth believing and betting, and that both the team and the venture are very active.” Another founder highlighted that the ET was particularly important to participate in many and different types of events (e.g., conferences, competitions, and specific fairs).

4.3 ET role: ECF post-campaign phase

In this last sub-section, we present the results of our data analysis which provides insights into the role of ET in the post-campaign phase. This phase represents a new starting point in the ECF journey where the ET is particularly involved and plays a crucial role for the survival and development of the crowdfunded venture.

First, our interviews revealed that ET members after ECF campaigns have to manage an enlarged corporate structure made up of new investors who have entered the venture (mainly with minority stakes). Several founders pointed out that managing relationships with many new people in the venture would have been more difficult without an active ET. At the same time, ET members are committed in engaging the crowd to actively participate in the life of the venture; one of the founders underlined that “new investors often ask for information and aim to play an active role in the development of the venture, not only to have economic returns soon, this is an excellent aspect for a young start-up like ours.” The ET engages not only in a conversation with the crowd of investors but—at the same time—also with some key stakeholders (such as reputable ventures, other industry players, and consumer associations).

This activity of crowd investor engagement was particularly useful for ET members, who benefited from the knowledge and the so-called “wisdom of the crowd.” ET members, in fact, revealed that investors participate in the development of the venture through valuable comments and opinions (held in high regard by ET), particularly focused on the opportunities to scale and grow, for example, through a specific marketing or internationalization strategy. One of the founders said “three highly motivated investors have many contacts with different types of international players in our sector and this aspect was fundamental for the growth of our venture as we were able to combine their knowledge and relationships with those of two members of our entrepreneurial team; the latter had similar ambitions of expansion in two of these foreign markets, but did not have sufficient knowledge or contacts, so the meeting between this ‘knowledge’ was decisive for the planning of our future strategies.” Likewise, other members highlighted that the reports provided by the new investors, who shared their networks and contacts, were very useful for the growth of the venture, and the presence of a larger team was crucial in managing all of these new relationships, and above all to do it in a more efficient way, thus avoiding the dispersion of useful contacts or the loss of precious opportunities. At the same time, members proactively take into account investor feedback, comments, and suggestions about products or services. These inputs are particularly useful to improve final products or to test new ones. About this aspect, an ET member said “our team is managing relations with new investors, and we have been able to gather some particularly useful feedback on our new experimental service that we will soon launch on the market; the improvement of this service is made possible thanks to some comments from investors particularly experienced in the field of distribution and information technology; without their help we would not have had this further phase of development, and it must also be said that the skills of one of our entrepreneurial team members were also complementary in this case.” Several precious considerations of some founders highlight that the ties formed with crowd investors during the ECF campaign can be transferred to business connections for ETs and represent for them a valuable opportunity for future cooperation, thus strengthening ties that were initially weak. A founder pointed out that “ties established with two investors in particular proved to be profitable and very useful in our case; we have a multi-year business relationship with them now, and they support us in various ways as well as create […and will create soon in the future, adds the founder…] strategic cooperations.”

From the interviews, two other fundamental aspects emerge related to the role of the team in the post-campaign phases. The first is the greater ability to mobilize new and often missing resources. An aspect similar to all the interviewees was the easier access to other and additional sources of finance. Some of the ET members highlighted that their ventures launched other ECF campaigns, while others have attracted the attention of some professional investors (e.g., Venture Capitalists). One of the founders, for example, said “our entrepreneurial team was very happy for the success of the first campaigns of equity crowdfunding, so we decided to start a second campaign; this was possible thanks to the efforts of the entrepreneurial team and the commitment of all of us.” The presence of an involved ET was useful to actively move into the market and search for new skilled human and financial resources. The good results obtained from the successful ECF campaigns have been decisive in attracting qualified personnel and new financial resources; however, as suggested by some founders, this was possible thanks to the presence of the ET who knew how not to waste the positive effects of the campaign and quickly seized the new opportunities offered by the market. Notably, the ET members revealed that after the ECF campaigns, they were able to access a valuable resource, namely tacit knowledge. In this sense, ET creates several valuable connections and gains access to tacit information, such as those of some crowd investors (who worked for existing ventures in the sector and the learning-by-doing process).

The last aspect that emerged from the interviews is the importance of ET after the ECF campaigns in building a venture’s robustness and resilience. This is a crucial aspect for ventures that are facing the current challenging scenario characterized by the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, the post-campaign phase was positive for all the ventures whose ET members, with great enthusiasm, in the wake of the success of the campaign, made great efforts to continue the development of the venture and keep the promises made to investors (e.g., what was described during the ECF campaign in terms of economic-financial projections and how the funds raised would be used); however, as is well known, the COVID-19 outbreak represented a devastating event for many businesses.

An intriguing aspect that emerged from the data analysis is that the equity crowdfunded ventures founded by the interviewed teams reveal an ability to withstand the condition of shock. Some of the founders, in fact, highlighted that the ET plays a vital role in maintaining functionality of venture operations and eventually in readjusting the configurations or changing some specific and necessary strategies (e.g., markets or long-term objectives) to cope with the shock.

A founder, for example, stated that “without an ET I think the effects of the pandemic scenario would have been more catastrophic for us; this is especially true because we have implemented rapid and effective collective actions focused on adapting to the new challenging scenario.”, while another one said that “thanks to our proactive ET, we were able to quickly change one of our services to address the COVID-19 pandemic emergency, and we changed some long-term goals.” Similarly, a founder declared that the pandemic scenario has led the ET members to decide the enter new markets (such as those of online services and e-commerce) to survive and absorb the shocks, but this represented also an opportunity for them to further develop new services and—hopefully—to increase their competitiveness in new markets.

5 Discussion

This qualitative study is among the first to specifically examine the role of ETs in the ECF context and leveraged a dynamic view allowing us to explore different phases in this sense, namely, the pre-campaign, during the campaign, and post-campaign phases. Figure 2 shows a final proposed model to explain the different phases of the ECF journey. While most studies use a static view and explore the central phase, i.e., the dynamics of ECF campaigns, our study tries to make further steps towards a better understanding of all the ECF phases, thus contributing to different research streams. The ECF literature is very vibrant, as underlined by several general calls for papers to increase knowledge in the entrepreneurship domain (Drover et al., 2017; McKenny et al., 2017; Short et al., 2017) and by specific calls to fill identified gaps, as in the case of pre-campaign or post-campaign phases (Coakley et al., 2022; Cummings et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2023; Stevenson et al., 2022; Walthoff-Borm et al., 2018a). Our study embraces the idea that a deeper exploration of ETs in ECF is needed and joins the debate in the literature. Overall, the research improves our knowledge of the roles of ETs in this less-explored context in entrepreneurship.

The findings show that in all the three phases, ETs have a key role and a specific importance by making a decisive contribution. As regards the pre-campaign phase, our findings highlight that ETs disclose a high level of entrepreneurial alertness, increasing the ability to identify and pursue opportunities (Tang et al., 2012). The ET members proactively search for information and exploit external resources more effectively (Ardichvili et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2020; Gaglio & Katz, 2001). This action seems to increase the likelihood to identify the best and new opportunities and to engage in novel contexts, in this specific case, the ECF context.

The analysis highlights that ETs play a crucial role in reducing or mitigating the uncertainty perceived, particularly environmental uncertainty. ET members act together in dealing with uncertainty and increase the willingness to bear it. In general, there is little information about the effects of new tools—in this specific case the ECF which recently entered the global arena (Block et al., 2018a)—on new firms, and this led to an increase in environmental uncertainty felt (Milliken, 1987). Entrepreneurship literature presents several contributions underlying the relationship between entrepreneurial action and the impact of uncertainty (Townsend et al., 2018). Among them, there is a consensus that increased uncertainty has negative effects on entrepreneurial activity (Townsend et al., 2018). Our results highlight that ET reduces this uncertainty and enhances entrepreneurial actions. Interestingly, in some cases, the ET managed to turn uncertainty into opportunity. This is because the uncertainty led to the identification of some specific opportunities.

The findings also reveal that ET members have a high level of social media use, which in turn led to improved venture efficiency and the formation of several entrepreneurial opportunities (Parveen et al., 2016; Troise et al., 2022b). Some studies show that entrepreneurs benefit from the use of social media in influencing opportunity recognition and resource mobilization (Fischer & Reuber, 2011). These effects are stronger in the case of ETs that emerge from our study; this is because the ET members access to a high number of connections through social media, manage these relationships efficiently, and—at the same time—acquire a valuable amount of information and knowledge.

Our findings embrace the thought of Brown et al. (2019) that networks and ties are leveraged by ventures through the different phases of their ECF journey. Both social media use and networks have emerged as valuable elements considered and leveraged by ETs in the pre-campaign phase and especially in its preparation (Cai et al., 2021). Scholars have provided evidence that these initial efforts, as well as the early stage of the campaigns, positively influence the success of ECF campaigns (Vismara, 2018). Our results show the importance of direct connections of ETs with several parties in this phase, thus supporting the view of previous studies (Brown et al., 2019; Lukkarinen et al., 2016). Furthermore, external networks such as private networks are a vital source of funding during the hidden phase of the campaign; scholars have provided evidence of external networks in this phase and that the higher these financial resources, the more successful the campaigns are (Brown et al., 2019; Lukkarinen et al., 2016). In this field, Lehner (2014) showed that direct and close social connections are essential both at the start of the ECF campaign and also during the preparation period, underlining that “success is based upon the social capital of the entrepreneurial teams” (Lehner, 2014, p. 478). Communication efforts by founders, such as in terms of posts, videos, and blogs, have positive effects on early backers’ attraction and numbers. Other studies underlined the importance of social capital and networks and have distinguished between in-crowd (with strong and weak ties with the founders) and out-crowd investors (no ties), revealing that the latter relies more on several types of information (financial planning, risks, etc.) (Polzin et al., 2018). Although it did not emerge from our interviews, a number of scholars support the idea that ECF platforms' feature lead professionals to attract follow-up investors (Agrawal et al., 2016; Xiao, 2020), and public profiles of investors attract early investors (Vismara, 2018).

Finally, ETs play a key role in improving the openness to new experiences and approaches for all the members (Slavec et al., 2017). This represents a strength for new ventures and helps them to be more open and proactively use new tools like the ECF. ETs disclose a high propensity for novelties and for evaluating external opinions or feedback. The latter is a crucial aspect for new ventures aiming at growth. At the same time, the ET members pay particular attention at the learning dimension, that is, to learn new approaches and leverage new knowledge for their own venture.

The campaign phase is the most investigated aspect in the literature, although the role of ET was just considered for its signaling power in terms of human capital signals. Our findings confirm previous studies that ET positively influences the success of ECF campaigns (Coakley et al., 2022). Specifically, the results highlight that the size, education, and previous experiences are particularly important during the campaign phase involving crowd investors to commit financial resources by signaling a good fit with venture quality (Piva & Rossi-Lamastra, 2018; Troise et al., 2022a). These signals reduce uncertainty for equity investors related to investing in a new venture and mitigate the information asymmetries between the parties.

The ET members proactively manage a high number of social interactions during the campaigns and promote the projects through a multitude of social media. Both social network ties and connections are particularly useful to get superior ECF performance (Lukkarinen et al., 2016; Polzin et al., 2018; Troise et al., 2020). In this sense, Vismara (2016) has shown that an external social capital form like social media networks predicts the success of ECF campaigns. Our findings are in line with other scholars who have argued that entrepreneurs proactively use social media to promote their crowdfunding campaigns and mobilize investors from their close networks but also—and above all—from the outside (Dorfleitner et al., 2018); in line with some evidence in the literature (Vismara, 2018), early investors engaged by ETs proved to be able to increase the funding success. The use by ETs of several social media tools and communication channels, as well as the number of information, comments, and updates with an easy language, represents all valuable sources to attract different classes of investors (Block et al., 2018b; Estrin et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2016). Interviewees underlined that ET members actively try to build new networks in the ECF campaign phase and have direct interactions with investors (Brown et al., 2019); at the same time, their close investors paid attention not only to financial returns but also to existing relationships with ET members (Polzin et al., 2018) and the trust generated, a typical feature of ECF platforms and the related online transactions. Also, the communication aspects are managed by ETs with great commitment; they, in fact, use (massively) a large number of tools, especially videos, pitches, and updates. The ET members are active in providing quick and precise updates and responses to investor’s comments and requests; this is perceived as a valuable aspect by investors, better than the actions of other employees given the more important role of founders. Put simply, they prefer direct interaction with ET members. Finally, ET members are more able to attract reputable investors, which in turn has a signaling effect on other investors. At the same time, the more the individual or venture certifications, the more the interest from third parties. The number of external certifications—such as awards, press, opinions, and recommendations—is positively evaluated by investors (Ahlers et al., 2015; Lukkarinen et al., 2016).

As regards the last phase, namely, the post-campaign one, significant aspects emerged from the analysis. The post campaign phase represents a new starting point of the ECF journey and not only the end, in fact, often this phase includes second rounds of financing (e.g., from professional investors) and additional operations such as internationalization and product co-creation processes (Troise et al., 2023a). The first aspect that has emerged is the crowd involvement and management, which represents a key activity of the ET. The ET is committed to managing relations with new investors and actively involves the investors in the venture’s life and activities. The second aspect is closely linked to the previous one and is the exploitation of crowd knowledge and networks. Previous studies highlighted that many entrepreneurs approached ECF strategically to get further additional resources such as knowledge and relationships and not only financial resources (Di Pietro et al., 2018; Troise & Tani, 2021). Our research suggests that team members have a greater ability to manage crowds, which generally risk being an underutilized asset (Di Pietro et al., 2018), and maximize these relationships. In fact, they efficiently exploit the inputs coming from the crowd both in terms of knowledge and network. The ET proactively adopts the best strategies to further develop the venture and evaluate as well judge the feedback from the investors. Prior studies have showed that ETs are more capable and willing to scale up their ventures compared to solo founder (Barringer et al., 2005; Ye et al., 2023); our research confirms this point of view and, in our case, the ETs benefit from crowd exploitation to further scale their ventures. In line with prior studies (Brown et al., 2019; Di Pietro et al., 2018), exploitation of crowd networks—and especially the development of relationships with key stakeholders—is crucial for the survival rates and performance of ventures. In this vein, Di Pietro et al. (2018) highlighted that these equity-crowdfunded ventures exhibited higher performance two years later, while Brown et al. (2019) suggested that weak ties formed in the ECF campaigns can be transferred to business connections for entrepreneurs and represent a valuable opportunity for them for future cooperation.

The third aspect that emerged is resource mobilization, a key activity for ventures (Bhagavatula et al., 2010; Troise et al., 2022b). After the ECF campaign, the ET is active in searching for new—often missing—resources, such as specific human resources (with high skills) and tacit knowledge. Similarly, the ET members disclose easier access to other sources of finance such as BAs, VCs, or other crowdfunding rounds. These aspects are related to the increased relationships of ET members with crowd investors and the capability to engage in conversations with other key stakeholders of the ecosystem. As suggested by Di Pietro et al., (2018, p. 57), in fact, crowd investors allow ventures to “bring the conversation to the next level of engagement.”

The last aspect that emerges from the study is the increased capability of the venture to resist or react to catastrophic events (Blečić & Cecchini, 2019; Munoz et al., 2022) like the current COVID-19 pandemic thanks to the engagement of ET members. The latter plays a vital role thanks to their commitment to create a new organizational equilibrium to face the challenging scenario and to rapidly change several objectives of the venture, such as long-term plans, product, or market strategies. Apart from the resistance to the changing environment, the ET allows the venture to cultivate and nurture an organizational resilience, useful to face future potential catastrophic events. These findings confirm the idea that ETs are more likely to have the necessary resources and conditions (e.g., skills, capabilities, knowledge, and expertise) to be ready to adapt and to navigate environments characterized by dynamicity, intense competition, changing market conditions, uncertainty, and complexity (Delmar & Shane, 2006; Eisenhardt & Schoonhoven, 1996).

Interestingly, it is possible to note that social capital represents a common parameter for the three phases, confirming its dynamic effect on ECF activities over time (Cai et al., 2021).

6 Conclusion

Our study improves our knowledge of the roles of ETs in entrepreneurship and specifically in the phases of the ECF journey. Studies exploring ETs in this specific context are still lacking in the literature, calling for additional studies. The research advances our understanding of ETs in ECF contexts and extends the current literature. In this sense, we aim to expand current literature mainly focused on the campaign phase and provide new evidence on the importance of ET in influencing the motivations/decisions to use ECF, its role during the campaign and after the campaign, especially in managing the venture growth in the follow-up scenarios.

Results of this research highlight that ETs play a crucial role in the entire ECF journey, and it has implications for studies of ET as well as those of ECF. ETs could have strategic roles for new ventures’ development, and their exploration in the ECF context represents a crucial opportunity to provide new insights in this field of research. Particularly, it is possible to underline the presence of three different phases in the ECF contexts, namely, pre-campaign, during the campaign, and post-campaign phases (Cai et al., 2021; Di Pietro et al., 2018; Signori & Vismara, 2018; Stevenson et al., 2022; Troise et al., 2021; Troise & Tani, 2021). Understanding the role of ETs is highly relevant for new ventures, and it will have several implications for many stakeholders involved in the development of ECF and in supporting entrepreneurial initiatives by ETs.

The study contributes to the entrepreneurship literature by showing the importance and actions by ET members in a context not yet fully investigated and the three phases of the ECF journey. Scholars have argued that the study of ETs is of more theoretical interest than solo-founder and allows to explore the social processes influencing new ventures (Brüderyl & Preisendörfer, 1998; Eesley et al., 2014). ETs are groups of people acting as a social force of change and adopting a collective endeavor, confirming that the ET dynamics are becoming increasingly relevant in the entrepreneurship literature. The investigated ETs contribute actively to some key actions of the entrepreneurial process, such as opportunity recognition and resource mobilization. The importance of ETs in ECF phases is perhaps mainly due to their characteristics, size, cohesion, and heterogeneity; as reported by many interviewees, the presence of an ET has multiplied the opportunities for ventures and the possibility of managing both the campaign and the subsequent relationships after it more efficiently. In addition to the entrepreneurship literature focused on the ET, the study contributes to the crowdfunding research field, and specifically, the research stream focused on ECF. In this field, the main stream explored the campaign phase, with a particular attention to the successful drivers of campaigns, while several sub-streams recently emerged, such as the post-campaign phase and pre-campaign phase (the latter focused on the entrepreneurial decision-making process activated before the launch of the campaigns). Our research contributes to the three streams and provides new insights into the ETs in this context, where the only results are related to the signaling role played by the ET in opposition to solo founders or, only recently, the likelihood of surviving or failing (Coakley et al., 2022).