Abstract

Existing research on family firms emphasizes the importance of entrepreneurship across generations but leaves the role of entrepreneurial transmissions between predecessors and successors relatively unexplore . Building on the concept of entrepreneurial legacy, we ask how interactions of entrepreneurial mindsets and resources influence organizational ambidexterity in family firms. The study’s central argument (and metaphor) is that organizational ambidexterity thrives in multigenerational family firms if successors’ awareness of the family’s entrepreneurial legacy (the right seed) interacts with predecessors’ provision of entrepreneurial resources during succession (the fertile soil), also known as entrepreneurial bridging. We analyze a unique sample of successors from 296 multigenerational family firms in the agricultural sector. Our results point to the relevance of entrepreneurial resources in predecessor-successor collaborations to unlock the family firm’s ability to balance entrepreneurial exploration and exploitation.

Plain English Summary

When predecessors and successors join forces in a family business, the company’s ability to blend old traditions with new ideas is enhanced. Suppose the successors are supported with resources and knowledge as they take over. In that case, the family’s entrepreneurial spirit is more likely to live on through the generations. Our study of 296 long-lived family farms found that when predecessors provide entrepreneurial resources, successors are better able to juggle the company’s traditions, current needs, and future challenges. Planting healthy seeds (a strong entrepreneurial spirit) in good soil (providing entrepreneurial resources) fosters successful succession. Thus, generations must work together to keep the entrepreneurial fire burning in family businesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nurturing entrepreneurship across generations matters for family firms (Kellermanns et al., 2012; Uhlaner et al., 2012; Zellweger et al., 2012). Prior research has emphasized the intergenerational flow of entrepreneurial mindsets (Barbera et al., 2018; Diaz-Moriana et al., 2020; Kammerlander et al., 2015; Salvato et al., 2010) and the resource exchange between multiple generations (Garcia et al., 2019; Hauck & Prügl, 2015; Kammerlander et al., 2020) as crucial determinants in the family firm’s ability to foster entrepreneurial exploration and exploitation (Goel & Jones, 2016; Stubner et al., 2012). To this end, the predecessor-successor relationship has been identified as essential in the entrepreneurial transmission across generations (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001; Dou et al., 2020; Hauck & Prügl, 2015; Marchisio et al., 2010; Rondi et al., 2019). Hence, one of the most sensitive periods for transgenerational entrepreneurship is the period of succession, when predecessors collaborate with successors for several years (Daspit et al., 2016; Jaskiewicz et al., 2015; Nordqvist et al., 2013).

However, we know relatively little about how the interplay of entrepreneurial mindsets and entrepreneurial resources in predecessor-successor relationships influence a family firm’s balance of entrepreneurial exploration and exploitation. Addressing this theoretical puzzle is essential for three reasons. First, while most prior literature on transgenerational entrepreneurship assumes consistency in entrepreneurial mindsets and resources across generations, the divergence between generational perspectives is a prevalent phenomenon in family firms (Magrelli et al., 2022; Miller et al., 2003). Second, extant succession research has mainly contributed to our knowledge of successful transitions (Daspit et al., 2016). However, we know less about how family firms can capitalize on their succession process to foster their ability to pursue organizational ambidexterity, that is, their ability to reconcile exploration and exploitation (March, 1991). Third, prior literature on organizational ambidexterity in family firms has indicated that entrepreneurship as the process of opportunity exploration and exploitation provides the “means” for family firms’ survival (Goel & Jones, 2016, p. 94). However, existing research on the role of entrepreneurial mindsets and resources in the bridging period of succession is limited.

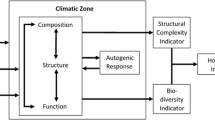

This paper sets out to investigate the interactive role that entrepreneurial legacy and entrepreneurial bridging play in influencing organizational ambidexterity in family firms. Successful family firms embed their entrepreneurial mindset into an entrepreneurial legacy—the family’s rhetorical reconstruction of past entrepreneurial achievements or resilience—and engage in complementary transgenerational collaborations that involve the provision of entrepreneurial resources—also known as entrepreneurial bridging (Jaskiewicz et al., 2015). Building on prior knowledge of transgenerational entrepreneurship, our main argument is that the interplay between successors’ perception of the family’s entrepreneurial legacy and their predecessors’ engagement in entrepreneurial bridging during succession shapes a firm’s organizational ambidexterity. Metaphorically, we propose a family’s entrepreneurial legacy to be the right seed and predecessors’ provision of entrepreneurial resources to be the fertile soil that establishes, in concert, organizational ambidexterity across generations in family firms.

We test our hypotheses in the context of family firms in the agricultural sector with a sample of 296 German family farms and specifically shed light on periods determining the transfer of farms to successors. The agricultural sector is an especially apt environment as (1) family farms heavily rely on and pass on history across generations (Suess-Reyes & Fuetsch, 2016), (2) family farms’ succession largely relies on family members (Fitz-Koch et al., 2018), and (3) family firms in the agricultural sector increasingly face dynamic environments, urging their need to pursue exploration and exploitation (de Roest et al., 2018). Our results confirm that the successor’s awareness of the family firm’s entrepreneurial legacy and the predecessor’s provision of entrepreneurial resources in the bridging period of succession significantly interact in forming the family firm’s organizational ambidexterity.

The paper makes several contributions to the academic and managerial discussion on transgenerational entrepreneurship. Most prior literature assumes that a family firm’s entrepreneurial legacy and the provision of entrepreneurial resources during succession are consistent and beneficial for transgenerational entrepreneurship (Jaskiewicz et al., 2015). We contribute to the literature by introducing the idea that the interaction between the successor’s awareness of the family’s entrepreneurial legacy and the predecessors’ provision of entrepreneurial resources is associated with increased (decreased) organizational ambidexterity. To this end, we extend knowledge on the relatively novel concept of entrepreneurial bridging and further enhance our theoretical understanding of the entrepreneurial resource provisions in family firms by empirically building on an established construct in the corporate entrepreneurship literature. Finally, we derive managerial implications for predecessors on intergenerational collaboration during succession to enable successors to live up to their family firm’s entrepreneurial legacy.

We structure our paper in the following way. First, we review the literature on transgenerational entrepreneurship to introduce the core logic of entrepreneurial legacy, entrepreneurial bridging, and organizational ambidexterity in family firms. Second, building on these concepts, we theoretically develop the seed-soil metaphor in our hypotheses. Based on our unique dataset of family-run farms in the agricultural industry, we find support for our hypotheses in our main and post hoc analyses. Finally, we conclude by discussing the theoretical and practical implications of the interplay between entrepreneurial legacy and entrepreneurial resources for transgenerational entrepreneurship and family firms.

2 Theoretical framework and hypotheses

The importance of balancing the continuity of existing businesses (i.e., exploitation) and pursuing innovative activities (i.e., exploration) in family firms has been the subject of extensive discussion. Against this background, prior research has found that transgenerational entrepreneurship, particularly the transmission of entrepreneurial mindsets and resources, is vital for family firms’ performance. However, these discussions have taken place separately. Accordingly, in our theoretical framework, we start by reviewing the literature on organizational ambidexterity to cast light on the antecedents of transgenerational entrepreneurship. We especially delve into the concepts of entrepreneurial legacy and entrepreneurial bridging, which form the foundation of our hypotheses on the interplay between entrepreneurial mindsets (i.e., the right seeds) and entrepreneurial resources (i.e., the fertile soil) for a family firm’s organizational ambidexterity.

2.1 Antecedents of transgenerational entrepreneurship in family firms

The prevailing idea that long-term competitiveness is most likely to be achieved if firms can flexibly adapt their strategy to environmental changes originated from perceptions that firms align their strategic orientation according to the environment in which they operate (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013). Thompson, (1967) revealed that deploying such a flexible strategic orientation while simultaneously adapting efficiently to the current environment triggers an administrative paradox for organizations. March, (1991) embedded the paradox between efficiency and flexibility into a theory of organizational learning that identified the fundamental organizational activities as exploration (activities such as discovery and experimentation) and exploitation (typified by refinement, production, and the execution of opportunities). Successful firms reconcile explorative and exploitative entrepreneurship by simultaneously balancing both strategies (Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996). Duncan, (1976) was the first to describe organizational ambidexterity, a concept that depicts the firm’s alignment of organizational structure and resource allocations to meet the conflicting demands of organizational environments (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013).

While research on organizational ambidexterity emphasizes an imbalance in favor of exploitation as explorative activities often run counter to business continuity (Lavie et al., 2010), such tensions are particularly salient in family firms. Exploration often conflicts with the essential goal of family firms for continuance (König et al., 2013). For instance, prior studies focusing on the link between such family influence and entrepreneurship highlight the family firm’s history (e.g., traditions, family networks, family roles) and the preservation thereof as salient determinants of a firm’s strategy (Jaskiewicz & Dyer, 2017; Laspita et al., 2012; Yates et al., 2022). De Massis et al., (2021, p. 5) state that “family firms often feel pressure to stay true to their legacy and founding conditions.” Because family firms’ history represents a significant part of their organizational identity (constituting the socio-cultural elements of the firm), they also guide the strategies of those family firms (Chirico & Nordqvist, 2010). Further, as family firms operate across multiple generations, the next generation of family managers has to find consensus among multiple generations involved in the business on balancing exploration and exploitation (Dolz et al., 2019; Kammerlander et al., 2020). Family business research emphasizes diverging generational preferences of the need for further exploration and exploitation, perhaps rooted in different generational cohorts (e.g., boomers vs. Gen X/Y) (Magrelli et al., 2022), tenure in the firm (Cirillo et al., 2021), or life stages (Gersick et al., 1997) and related preferences for entrepreneurship. Such generation-spanning business activities make family firms “idiosyncratic” in their decision to balance exploration and exploitation, constituting a salient determinant for successful organizational ambidexterity (Goel & Jones, 2016). Thus, to explore how family firms pursue organizational ambidexterity, we draw on the concept of transgenerational entrepreneurship.

Transgenerational entrepreneurship describes the exchange between generations to foster family firms’ strategic behavior to benefit current and future generations (Habbershon et al., 2010). That is, the current generation might favor exploitation of what they have built, while the next generations want to put their stamp on the family firm by exploring “as well as…their forebears” (Diaz-Moriana et al., 2020; Fox & Wade-Benzoni, 2017; Lansberg, 1999, p. 5). Creating entrepreneurial value that benefits current and future generations requires successors to engage in the “exploration of new ways of doing things and at the same time through the exploitation of existing products” (Habbershon et al., 2010, p. 4). Satisfying such preferences of the current (i.e., exploitation) as well as one’s own generation (i.e., exploration) might be driven by how well the successor can deal with (intergenerational) conflicts and ambiguity of exploration and exploitation (Lubatkin et al., 2006). Thus, successful transgenerational entrepreneurship depends on how well the successor fosters an intergenerational balance between a family firm’s ability to develop new products flexibly—according to new environmental circumstances faced by the next generation—and the continued exploitation of existing products—based on the work of prior generations (Duncan, 1976; March, 1991). Consequently, organizational ambidexterity represents a suitable performance outcome for successful transgenerational entrepreneurship.

According to transgenerational entrepreneurship, the two antecedents stemming from the family influence generating entrepreneurial value across generations are the family’s entrepreneurial mindset and the unique resources derived from such influence (Habbershon et al., 2010). The entrepreneurial mindset describes the values and attitudes shared by family members regarding entrepreneurship (Habbershon et al., 2010). Because the continuous flow of the family’s entrepreneurial mindset across generations is of utmost importance for maintaining a consensus among family members, research has explored how families approach the intergenerational transmission of their mindset. In particular, these values and attitudes are linked to their history embedded, for instance, in compelling stories of past entrepreneurship (Dalpiaz et al., 2014), metaphors (Discua Cruz et al., 2020), and traditions (Suddaby & Jaskiewicz, 2020). This emotional attachment to organizational history probably triggers a family’s shared understanding of the necessity to preserve its history and, in turn, influences its economic and non-economic goals (Goel & Jones, 2016; Kammerlander et al., 2020).

Jaskiewicz et al., (2015) suggest that succession is an apt period for transgenerational entrepreneurship. However, we know less about whether and how succession fosters entrepreneurship. This is surprising because multigenerational involvement is particularly salient during succession; hence, it can provide a promising context for family firms’ transgenerational entrepreneurship (Nordqvist et al., 2013). Some research has explored the outcomes of a family’s entrepreneurial mindset (Criaco et al., 2017; Hahn et al., 2021; Zellweger et al., 2011) or family resources (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2018; Hauck & Prügl, 2015) during succession on successors’ entrepreneurship. Nevertheless, most succession literature does not address how family firms can capitalize on their family resources to pursue exploration and exploitation ambidextrously (Goel & Jones, 2016).

Jaskiewicz et al., (2015) argue that successful family firms embed their entrepreneurial mindset into an entrepreneurial legacy—the family’s rhetorical reconstruction of past entrepreneurial achievements or resilience. Shared stories depict an important legacy artifact (e.g., Hammond et al., (2016)). Research indicates that stories emphasizing entrepreneurship and resilience help family members construct and develop entrepreneurial opportunities while contextualizing uncertainty during the entrepreneurial process within the broader context of past challenges (Barbera et al., 2018; Discua Cruz et al., 2021). While an entrepreneurial legacy can stimulate transgenerational entrepreneurship within the family, including the development of radical and incremental innovation (Kammerlander, Dessì, et al., 2015), it may also contribute to the pursuit of entrepreneurial careers outside the family firm (Combs et al., 2023).

Further, family resources describe the unique resources and capabilities resulting from family influence (Habbershon et al., 2010). Since resources are often exclusively assigned to predecessors during succession (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001; Handler, 1990), the extent to which successors pursue entrepreneurship within the organizational setting depends on whether predecessors ensure successors’ leeway to engage in entrepreneurship (Ireland et al., 2009). Jaskiewicz et al., (2015) showed that to achieve successful transgenerational entrepreneurship, predecessors engage in entrepreneurial bridging by granting their successors autonomy, sufficient time, and management support by providing human and financial resources, and rewarding success. Prior research in established firms has shown that providing such entrepreneurial resources fosters corporate entrepreneurship—the entrepreneurial behavior in existing firms (Stopford & Baden-Fuller, 1994). Organizational preparedness for corporate entrepreneurship (OPCE) has been conceptualized as a key construct in this domain (Hornsby et al., 2013). Notably, the initial conceptualizations of the OPCE construct by Kuratko et al., (1990, 2005) have greatly influenced intrapreneurship research and are widely cited in the field (for a comprehensive literature review, see Hernández-Perlines et al., (2022)). Building on this foundation, Hornsby et al., (2013) further refined the OPCE scale, developing a set of organizational resources that foster employee-driven entrepreneurial initiatives. These resources include management support, work discretion, reinforcing rewards, and time availability. While previous research suggests a direct effect between OPCE and a firm’s entrepreneurial outcomes, such as financial performance (Kreiser et al., 2021), recent research has emphasized the role of individuals’ entrepreneurial mindset in leveraging these provided resources or perceiving them as constraints for their intrapreneurship (Niemann et al., 2022). Thus, in the hypotheses section, we not only theorize on the separate influences of entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE on a firm’s organizational ambidexterity but also examine the interaction between OPCE and the successors’ interpretation of the family’s entrepreneurial legacy.

2.2 Entrepreneurial legacy and transgenerational entrepreneurship

First, a strong entrepreneurial legacy helps successors reconcile exploration and exploitation during succession. Successors with a solid entrepreneurial legacy likely view entrepreneurship as a fundamental aspect of their family’s entrepreneurial mindset and may therefore feel a sense of obligation to continue pursuing entrepreneurial endeavors (Clinton et al., 2020; Discua Cruz et al., 2020; Kammerlander, Dessì, et al., 2015; Sasaki et al., 2020; Suddaby & Jaskiewicz, 2020). This can lead them to see change and exploration as a way to stay true to the entrepreneurial legacy rather than conflicting with it. As a result, they may feel more comfortable taking on various tasks and engaging in different entrepreneurial activities while maintaining a sense of continuity with the family’s history. By doing so, they may be able to mitigate potential conflict and discord among generations (Kellermanns et al., 2012), as they can treat exploration not as conflicting to exploitation but both as legitime and necessary means to behave in accordance with their entrepreneurial legacy. Such continuance of the family’s entrepreneurial legacy by attaining both exploration and exploitation signals successors’ commitment to the family firm (Schell et al., 2020), their values (Riviezzo et al., 2015) and fosters legitimacy of successors’ entrepreneurship among family members (Dalpiaz et al., 2014).

Second, an entrepreneurial legacy incorporates entrepreneurial stories that motivate successors to continue the family’s legacy by engaging in organizational ambidexterity. Specifically, the founding story of a firm and how ancestors of the family successfully engaged in entrepreneurship can have lasting impacts on the entrepreneurial behavior of subsequent generations (Jaskiewicz et al., 2015; Johnson, 2007; Kammerlander, Dessì, et al., 2015). Research on innovation through tradition highlights the role of past entrepreneurial endeavors in guiding and inspiring successors, encouraging them to explore while preserving the existing business (De Massis et al., 2015; De Massis et al., 2016; Erdogan et al., 2020). In this way, entrepreneurial legacies can encourage successors to engage in ambidextrous behavior as they seek to preserve and build upon the legacy of the family firm. Further, stories of resilience incorporated into the family’s entrepreneurial legacy increase successors’ awareness of the necessity of entrepreneurship for survival (Jaskiewicz et al., 2015). Such stories narrow successors’ cognition regarding entrepreneurship to focus on incremental innovation of existing products, as this kind of innovation has probably ensured the family firm’s survival during harsh times (Chrisman et al., 2011).

Accordingly, an entrepreneurial legacy facilitates successors’ pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities by providing them with inspiration and legitimacy to implement change effectively. The more successors interpret the family firm’s legacy as entrepreneurial, the greater the likelihood that they will reconcile exploration and exploitation, thereby fostering organizational ambidexterity. Therefore,

Hypothesis 1: The successors’ perception of the family firm’s entrepreneurial legacy is positively related to the firm’s organizational ambidexterity.

Next to the desirability of entrepreneurship based on the family’s legacy, a key pillar of transgenerational entrepreneurship is the family firm’s provision of resources for entrepreneurial behavior (Habbershon et al., 2010). Successors who more strongly perceive predecessors’ efforts to foster OPCE are more likely to engage in entrepreneurship because they are better able to flexibly adapt to environmental changes by strengthening the core business (Ireland et al., 2009; Jaskiewicz et al., 2015; Kuratko et al., 2005), thereby strengthening organizational ambidexterity.

We argue that successors’ perceived OPCE leads to organizational ambidexterity for the following reasons. First, successors might feel obligated to reciprocate their predecessors’ provision of resources when utilizing them for entrepreneurship (Ekeh, 1974). Because predecessors in family firms tend to strongly identify with the firm that depicts an extension of themselves (Deephouse & Jaskiewicz, 2013), they prefer the continuance of the existing business. Successors who perceive a strong OPCE likely recognize the value of such resources for entrepreneurship and appreciate their predecessors’ provision as transgenerational support for entrepreneurial endeavors. Such enhanced entrepreneurial cooperation between predecessor and successor can lead to successors’ reconciliation of aspirations for exploration with predecessors’ aspirations for exploitation as an appropriate way to reciprocate predecessors’ efforts to foster OPCE.

Second, the vivid transgenerational collaboration resulting from predecessors’ efforts to foster OPCE can leverage successors’ entrepreneurial capacity to engage in different tasks. Transgenerational collaborations are one outcome of entrepreneurial bridging as it requires predecessors’ commitment to and engagement in successors’ entrepreneurship (Jaskiewicz et al., 2015). Hence, OPCE likely facilitates organizational ambidexterity as predecessors possess rich tacit knowledge, stemming, for instance, from the experiences they have made (Joshi et al., 2011), beneficial for the exploitation of the existing business (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2018), while successors bring in new knowledge and are more willing to take the risk (Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2006; Zahra, 2005). For example, Jaskiewicz et al., (2015) highlight that successful OPCE is characterized by transgenerational collaborations in which predecessors provide operational support for successors to ensure them the time needed to pursue exploration. Arguably, synergies arising from the complementary abilities of predecessors and successors during entrepreneurial bridging depict a salient driver for their organizational ambidexterity.

In sum, successors’ perception of OPCE helps family firms pursue exploration and exploitation ambidextrously because successors’ entrepreneurship is effectively navigated and complemented by predecessors’ involvement during transgenerational collaboration. The more successors perceive an entrepreneurial organizational environment during succession, the greater the likelihood that the family firm achieves organizational ambidexterity. Therefore,

Hypothesis 2: The successors’ perception of the family firm’s organizational preparedness for corporate entrepreneurship (OPCE) is positively related to the firm’s organizational ambidexterity.

While we theorized on the separate influences of entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE on organizational ambidexterity, we argue that they interact in shaping organizational ambidexterity in family firms. Most literature, including Jaskiewicz et al., (2015), consider entrepreneurial legacy and bridging as simultaneously present (Diaz-Moriana et al., 2020; Dou et al., 2020; Garcia et al., 2019). However, since a family’s legacy is subject to rhetorical interpretations of individuals (Suddaby et al., 2010) and likely differs among family members (Barbera et al., 2018; Sasaki et al., 2020), consistent legacy perceptions across generations might not hold (Eze et al., 2021).

In line with that, other streams of research highlighting inconsistencies between what predecessors ought to provide to foster the successors’ entrepreneurship are prevalent in family firms and one key factor hindering family firms from prospering across generations (De Massis et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2003). For instance, the inconsistencies between predecessors’ preservation of their (family’s) legacy and successors’ attempts to make their own mark on the family’s legacy might interfere with the transmission of the family’s legacy (Suddaby & Jaskiewicz, 2020). Consequently, interpretations of the family’s legacy can vary between different generations of family members (Suddaby et al., 2010). Accordingly, we explain in the following how entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE interact in their influence on organizational ambidexterity (see Fig. 1).

2.3 Interaction between entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE

In a situation where successors with a strong entrepreneurial legacy perceive a strong OPCE, the successors’ motivation to engage in organizational ambidexterity is fostered and navigated through the entrepreneurial environment predecessors provide. OPCE regards successors with the resources suitable for responding to environmental changes by strengthening the existing business (Kuratko et al., 2005). This transmission of decision power of resources towards successors helps them consciously leverage their attempts to engage in exploration and exploitation. Successors can leverage the resources provided because they are motivated for entrepreneurship, have the entrepreneurial mindset to recognize opportunities for engaging in exploration and exploitation, and perceive predecessors’ legitimacy for their plans who might use their entrepreneurial bridging to navigate successors’ entrepreneurship toward organizational ambidexterity (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001). Like right seeds that prosper on fertile soil, perceiving a strong OPCE leverages the value of entrepreneurial legacy to foster the effect of successors’ entrepreneurial legacy on organizational ambidexterity.

When a successor interprets the entrepreneurial legacy as weak and does not strongly perceive an OPCE, one possible strategic consequence would be to adopt a policy based exclusively on continuing the family’s legacy in accordance with the predecessors’ provided resources. Thus, successors feel confirmed in their conservative behavior (Criaco et al., 2017) and perceive no awareness of fostering organizational ambidexterity as they lack predecessors’ support for entrepreneurship (Jaskiewicz et al., 2015). Further, predecessors stifle successors’ aspirations during succession by constraining their capacity to implement them (Huang et al., 2020). While successors’ aspirations neglect predecessors’ legitimization as they do not consider the family’s legacy, the constrained resources through low OPCE further mitigate successors’ chance of pursuing entrepreneurship. Consequently, such a constellation, in which bad seeds fall on rocky soil, hampers the organization’s ambidexterity as predecessors’ reluctance to foster OPCE enforces the negative effect of a lack of entrepreneurial legacy on organizational ambidexterity.

Furthermore, when successors face a strong (weak) entrepreneurial legacy and perceive the OPCE as weak (strong), they are exposed to uncertainty about whether they should and can foster organizational ambidexterity. When successors’ entrepreneurial legacy is high, but they perceive a low OPCE, their quest to continue the entrepreneurial legacy is interfered with by the dearth of an appropriate entrepreneurial environment. Predecessors play a crucial role in providing the knowledge, experiences, and resources necessary for successors to continue and build upon the family’s entrepreneurial legacy (Cruz & Nordqvist, 2012). However, in some cases, predecessors may use their power and influence to impede the successors’ ability to explore new business opportunities, also known as the founder’s or predecessor’s shadow (Davis & Harveston, 1999). The founder’s shadow likely establishes when the predecessors leave harmful traces on the established social relations and routines (Davis & Harveston, 1999). This can prevent successors from fully leveraging their own skills and experiences gained externally, such as work experience (Chirico & Nordqvist, 2010; Nordqvist et al., 2013), to create new combinations of existing products (Schumpeter, 1934).

One example of this can be seen in a study by Radu-Lefebvre et al., (2022), which illustrated how a lack of predecessors’ entrepreneurial bridging has led to the successor’s emancipation from the predecessors’ shadow. In order to stay true to their entrepreneurial legacy, the successor escaped from the predecessors’ power during succession by founding a new and separate venture instead of continuing as leader of the established family firm. While this may seem like an extreme outcome, many successors who encounter a strong entrepreneurial legacy but a lack of support from their predecessors may choose to remain obedient to their predecessors but carry out the power conflict during succession (Davis & Harveston, 1999). As a result, their desire for exploration and exploitation may fade over time. Consequently, successors perceiving a low level of OPCE are hindered from turning their perception of a family’s entrepreneurial legacy into organizational ambidexterity since predecessors discourage their entrepreneurial activities and navigate successors to work in, but not on the business—right seeds falling on rocky soil grow but cannot reach their full potential.

When successors have a low entrepreneurial legacy but perceive a high level of OPCE, they might struggle to utilize those provided resources for pursuing exploration and exploitation. The value of these resources is often dependent on the expectations of the family (Sieger & Minola, 2017), and successors with a weaker entrepreneurial legacy might perceive that utilizing such resources for exploration runs counter to the continuance of the family’s legacy and their family’s desire (Pittino et al., 2018). Accordingly, successors feel compelled to continue the family’s legacy, even if it hinders them from fully leveraging those resources to balance exploration and exploitation. This can make the entrepreneurial bridging feel like a “poisoned gift” (Sieger & Minola, 2017), as it appears valuable on the surface but is hindered by obligations to the family that restrict the successors’ ability to foster organizational ambidexterity. Just as bad seeds will not flourish on fertile soil, a less entrepreneurial legacy prevents successors from capitalizing on the entrepreneurial resources provided by their predecessors.

In conclusion, transgenerational collaborations between predecessors and successors are most effective when successors with a strong entrepreneurial legacy face a strong OPCE—that is, a situation in which the right seeds (i.e., strong entrepreneurial legacy) fall on fertile soil (i.e., strong organizational support for entrepreneurship). Therefore,

Hypothesis 3: The interaction between the successors’ perception of the family firm’s entrepreneurial legacy and the organizational preparedness for corporate entrepreneurship (OPCE) enhances organizational ambidexterity.

3 Method

3.1 Data collection

To investigate the influence of perceived entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE on a family firm’s efforts to foster organizational ambidexterity, we draw on a sample of German agricultural family farms for several reasons. First, the long history of German family farms means that there are often multiple generations of entrepreneurs within a single family, providing a rich source of entrepreneurial legacy that can shape the shared perceptions of entrepreneurship within the family (Fitz-Koch et al., 2018). Second, the close-knit nature of many German family farms—family members usually live and work together on the farm side, and children of farmers are exposed to all aspects of the work their parents do—means that there is often a strong sense of shared responsibility and interdependence between family members, which can facilitate the transfer of knowledge and resources during succession (Delmas & Gergaud, 2014; Hadjielias et al., 2021; Seuneke et al., 2013). Third, intra-family farm transition is the predominant form of succession (Glover & Reay, 2015). While farms may exhibit path dependency due to their long history, the succession process serves as a trigger event that prompts farms to reassess the status quo and break away from previous trajectories by establishing new practices (Sutherland et al., 2012).

Further, the transition to one controlling owner-child is not only widely practiced but is also legally mandated in certain federal states, as required by the Farm Inheritance Law introduced by the Federal Ministry of Justice in 1947 (“Hoefeordnung”). The farms falling under the purview of this law are often characterized by a single-owning family and a minimum size that would allow a family’s livelihood and, hence, are managed professionally. Thus, it is plausible to expect a substantial prevalence of family ownership among German family farms. In such cases, family members’ collective perceptions and values can significantly impact the firm’s direction and decision-making (Suess-Reyes & Fuetsch, 2016). Finally, the latest reforms in the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) have shifted towards promoting a more market-oriented approach, encouraging farmers to enhance their entrepreneurial behavior (de Roest et al., 2018; Vesala & Vesala, 2010). These reforms reflect a departure from the previous modernization paradigm focused on intensification and specialization for economies of scale. However, with the liberalization of agricultural markets, as well as changing market demands and weather patterns, family farms are increasingly required to be adaptable and efficient in order to survive (Fitz-Koch et al., 2018). Consequently, entrepreneurship research has increasingly recognized the significance of the agricultural industry (Dias et al., 2019a, 2019b). Family farms have particularly gained attention as valuable subjects for studying transgenerational entrepreneurship, exemplified by studies on wineries (e.g., Jaskiewicz et al., (2015); Kammerlander, Dessì, et al., (2015)) and dairy farms (e.g., Glover & Reay, (2015)). Successfully balancing exploration and exploitation is, hence, critical for the success of family farms.

To obtain a comprehensive sample, this research draws on official, publicly available lists of agricultural farms that are authorized to provide apprenticeships in Germany (Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, 2019). In Germany, farms can be quite diverse, with some being small, part-time operations or micro-farmers who cultivate a small number of hectares and others being large, industrial farms with many employees. To ensure a homogenous sample of family farms that are large enough to be the main source of income for the family but still fully family-owned, we restricted the upper and lower levels of farms. Because the apprenticeship license is tied to the person rather than the farm, the farm owners are likely to be actively involved in the day-to-day operations of the farm in order to provide hands-on education to their students. This means those farms are likely large enough to provide full-time employment for the manager.

Additionally, to ensure the focus on family-owned multigenerational farms, we excluded farms located in the Eastern part of Germany. During the 1950s in Europe, a significant transformation occurred in the agricultural practices of the Eastern communist bloc, as they implemented a policy of enforced collectivization, consolidating small farms into large-scale operations. In contrast, family ownership and smaller-scale farming persisted in the West. This divergence led to the consolidation of over 800,000 family-owned farms into a mere 20,000 cooperatives within the Eastern bloc (Batáry et al., 2017). Although the size of the fields remained largely unchanged after the German reunification in 1990 (Baessler & Klotz, 2006), the ownership shifted from cooperatives to private entities, often involving foreign (non-family) investors (Batáry et al., 2017). Consequently, while many farms are currently owned by investors, those under exclusive family ownership and management have only emerged since 1990 at the earliest. Due to significant differences in economic development even after the reunification, other studies on small businesses and entrepreneurship have also focused on samples either in Eastern or Western Germany. For instance, Constant & Zimmermann, (2006, p. 283) explain their empirical focus on West Germany as follows: “Even a decade after unification, East Germans do not have significant experiences with self-employment.“

A total of 4146 invitations were emailed to current or future owner-managers of training farms in Western Germany, of which 3965 were operational, inviting them to participate in an online surveyFootnote 1 exploring their experiences as successors. The email included a link to the questionnaire. Two reminders were sent 1 and 2 weeks after the initial invitation in November 2019. Ultimately, 385 questionnaires were returned, yielding an initial response rate of 10.3%. We selected respondents according to our understanding of a family firm as a business where the family has a significant influence on the firm (Chua et al., 1999). Contextualized to the agricultural farms, we applied five selection criteria: (1) the farm must have been managed full-time by a family member, (2) succession took place or would take place inter-generationally, (3) participants must either have already taken over the business from their parents or be in the process of taking over the business within the next 5 years, (4) participants must have actively worked alongside the predecessor after finishing full-time education, and (5) participants must have been actively involved in the business for at least 2 years. Ultimately, we obtained a sample of 296 responsesFootnote 2.

3.2 Nonresponse bias

To control for possible bias caused by nonresponses, we first tested the representativeness of our sample by comparing farm characteristics with data from the Federal Statistical Office, which conducted an agricultural census in 2020 (Federal Statistical Office, 2020). Farms from our sample employ more labor (2.7 vs. 1.4), and the share of respondents with a university degree is higher among our sample (24.6% vs. 7.1%) compared to the average German farm in the West. These differences are reasonable, given that the farms in our sample are all qualified to train apprentices, which implies that these farms often employ apprentices, and farmers must provide proof of a higher education degree. Compared to the average German farm in the West, our sample consists of more farmers under 45 (42.6% vs. 21.6%) and fewer women (5.1% vs. 11.1%). In conclusion, the comparison suggests that our sample is representative of the average German farm in the West.

Further, the family has owned the average farm from our sample for 202 years. Hence, we likely rule out potential influences from different generational transfers (e.g., first- vs. second-generation successors) and resulting differences in the way that successors approach their roles depending on the generation they belong to (Cruz & Nordqvist, 2012).

Second, we controlled for nonresponse bias by comparing subsamples of the data. We followed the recommendations by Armstrong & Overton, (1977) and divided the sample into early (earlier 50%) and late (later 50%) respondents, as well as respondents who completed the survey within a shorter (shorter 50%) and a longer time interval (longer 50%) to compare whether the subgroups differ in their responses. No statistically significant differences were found for both explanatory variables (entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE) by using t tests. Altogether, this indicates that our results are unlikely to be distorted by nonresponse bias.

3.3 Measures

All constructs of the dependent and independent variables included in the questionnaire were measured on 5-point Likert scales, anchored with strongly disagree (1) and strongly agree (5). The questionnaire was adapted to suit the agricultural context and then pre-tested on ten farmers.

To collect data on our dependent variable, the respondents were asked to assess organizational ambidexterity over the preceding 3 years. The dependent variable is based on the scale of Lubatkin et al., (2006). This scale has a solid theoretical and empirical foundation, as it incorporates and expands upon previous conceptualizations of organizational ambidexterity by He & Wong, (2004) and Benner & Tushman, (2003). The scale has been validated for use in small and medium-sized firms, and its applicability has been demonstrated in studies involving such firms influenced by family dynamics (e.g., Kammerlander et al., 2015) and operating in stable industries (e.g., Dolz et al., 2019). These characteristics are central to our study context. Exploration and exploitation were measured through six items each. Exploration was assessed by items such as “The farm looks for novel technological ideas by thinking outside the box” and “The farm bases its success on its ability to explore new technologies,” while exploitation was assessed by items such as “The farm commits to improve quality and lower cost” and “The farm continuously improves the reliability of its products and services.” The reliability of the set of indicators was acceptable for both constructs, given Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 for exploration and 0.74 for exploitation (Hair Jr. et al., 2010). Following established literature, we treated exploration and exploitation as interdependent constructs and computed organizational ambidexterity by multiplying the means of exploration and exploitation, in line with previous studies (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004; Junni et al., 2013). We report the results of the robustness checks for both additive and subtractive ambidexterity below.

The first independent variable is entrepreneurial legacy. Entrepreneurial legacy was measured using a four-item index. The items were extracted from previous work on entrepreneurial legacy. In accordance with the method of Jaskiewicz et al., (2015), the first and second items measure the successor’s sense of entrepreneurial history: “I am aware of my family’s past entrepreneurial behavior and resilience” and “I am proud of my family’s past entrepreneurial behavior and resilience.” Since the objective past is wrapped in stories that anchor the reality in the context of the family’s values and attitudes (Barbera et al., 2018), the third item is, “I know many stories about my family’s past entrepreneurial behavior/resilience.” Finally, we assessed whether or not the successor is upholding and maintaining the entrepreneurial mindset established by previous generations (Dalpiaz et al., 2014): “My behavior is in line with my family’s entrepreneurial legacy.” The reliability of the set of indicators was acceptable, resulting in a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82.

The second independent variable is organizational preparedness for corporate entrepreneurship (OPCE). OPCE depends on the extent to which predecessors ensure work discretion for the successor, provide them with sufficient time, ensure management support by providing human and financial resources, and reward success (Hornsby et al., 2013). The scale consists of 18 items that load on four factors assessing the extent to which middle managers perceive that their firm nurtures intrapreneurial activities through management support (e.g., “When I came up with innovative ideas on my own, I often receive the predecessor’s encouragement for my activities”), work discretion (e.g., “I felt that I was my own boss and did not have to check all of my decisions”), time availability (e.g., “My workload was appropriate to spent time on developing new ideas”), and rewards and reinforcement (e.g., “The rewards I received were dependent on my work on the job”). As successors in small family firms take on responsibilities often comparable to those of middle managers in larger organizations soon after joining the firm, the scale should be well suited for assessing certain aspects of the successor’s perception of the predecessor’s entrepreneurial bridging. To increase the content validity of the items, we adapted the items slightly to ensure they were relevant to successors in small family farms rather than middle managers in larger organizations. The Cronbach’s alpha for OPCE was 0.92, demonstrating good reliability.

The method employed also controlled for confounding variables at the firm, family, and individual levels. First, we controlled for firm characteristics. Firm age and firm size are viewed as control variables in line with organizational ambidexterity literature (Lubatkin et al., 2006). The firm’s age was assessed in years, and the firm’s size was assessed by using the number of full-time employees. Finally, the industry dummy of grazing livestock considers potential environmental influences, as 43% of all farms belong to this category based on the statistical classification of agricultural enterprises in the European Union (EU Commission, 2014). Second, concerning influences of the family, we controlled for family cohesion because cohesive families (Jaskiewicz et al., 2015) and especially a close predecessor-successor relationship (Lee et al., 2019) might support the implementation of a successor’s entrepreneurial ideas (Habbershon et al., 2010). In line with Jaskiewicz et al., (2015), we utilized Bloom, (1985) five-item scale to assess family cohesion. The scale refers to the degree of connectedness and emotional bonding among family members (e.g., “Family members really helped and supported one another”). Cronbach’s alpha is 0.91, suggesting satisfactory reliability. Third, we controlled for individual characteristics, that is, we controlled for experience-related factors, including the successor’s age and their tenure as the owner-CEO of the firm, because extant research indicates those factors can influence the ability of individuals to foster organizational ambidexterity (Kammerlander et al., 2020; Mom et al., 2019) and the successor’s level of education (“1” for a university degree and “0” otherwise). We also controlled for gender (“0” for males and “1” for females) because risk-taking can be less pronounced among female managers (Zuraik et al., 2020).

3.4 Assessment of construct validity and reliability

Construct validity was assessed through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The final set of items of the dependent and independent variables, standard factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and Cronbach’s alphas for each construct can be found in Table 3 of the appendix. Although the chi-square statistic is significantly below the 0.001 level, which might be affected by sample size and model complexity (Hu & Bentler, 1999), the CFA shows good results, indicating an acceptable goodness-of-fit. The GFI is 0.846, the adjusted GFI (AGFI) 0.823, the normed-fit-index (NFI) 0.833, the incremental-fit index (IFI) 0.908, the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) 0.9, the root-mean-square-residual (RMR) 0.077, and the RMSEA value 0.054. Although the model does not meet the recommended threshold of 0.9 for GFI, the obtained value for the absolute fit index of TLI scores is well above 0.9, and the RMSEA lies below the threshold of 0.07 (with a CFI of 0.908); the measures as a whole thus support the assertion of the model’s goodness-of-fit (Hair Jr. et al., 2010).

Convergent validity was determined from the construct by estimating the standardized factor loadings of each indicator and the construct reliability, thus following (Hair et al., 2010). Convergent validity can be considered acceptable, construct reliability values were all above 0.7, and all factor loadings exceeded the 0.5 level except for two items of the exploitation construct. The factor loadings of the items “the farm commits to improve quality and lower cost” (0.35) and “the farm increases the levels of automation in its operations” (0.33) are below the conventional cutoff threshold but were retained in the analysis to ensure comparability with other studies employing the measure. However, all hypotheses were also significant when excluding the two items from the exploitation.

To measure the discriminant validity between the three constructs, we compared the AVE values with the squared correlation between any two constructs (not reported here). The constructs show discriminant validity when the AVE scores for two constructs exceed the related squared correlation of the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). This criterion was met for all constructs, thus establishing their distinctiveness. Further, CFA for the OPCE scale revealed a high correlation between the two latent variables: “rewards/reinforcement” and “management support” (0.79). Despite the relatively low AVE value of “rewards/reinforcement” (0.32), we assessed whether our model’s findings remain consistent when excluding the “rewards/reinforcement” variable from the OPCE scale. The results obtained from this modified model were comparable to those of our initial analysis.

To mitigate the chance of common method bias (CMB), we guaranteed the respondents’ anonymity and randomized the question order (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Further, we applied the marker variable technique (Podsakoff et al., 2003) to assess CMB ex-post. Following the guidance of (Williams et al., 2010), we used the three-phase CFA marker approach by integrating a theoretically unrelated variable into the research construct. That marker variable is planning (a four-item scale) from the long-term orientation scale developed (Bearden, 2006). In line with the suggestions of Williams et al., (2010), the marker variable is neither unrelated nor does it have strong theoretical and empirical relationships with the substantive variables. A comparison of the fit indices of the baseline model and method C model (Δχ2 difference chi-square = 59.353, p < 0.001, Δdf = 1) revealed that CMB could well be present; however, a comparison of the method-C model and the method U model (Δχ2 = 77.591, p < 0.001, Δdf = 33) suggests that CMB was not consistent across all indicators. Moreover, a comparison of the method U model and the method R model (Δχ2 = 16.6, p = ns., Δdf = 21) revealed no evidence of CMB distorting the relationships in the regression models.

4 Results

Our research focuses on examining the role of entrepreneurial legacy and bridging in fostering organizational ambidexterity within family firms. Drawing upon the concept of transgenerational entrepreneurship, we argue that the interpretation of entrepreneurial legacy by successors (H1) and their perception of OPCE (H2) positively influence the firm’s organizational ambidexterity. Moreover, we hypothesize that the interaction between entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE enhances the relationship with successful organizational ambidexterity (H3). In the following sections, we will present a comprehensive overview of our results, including the main effects, interaction analysis, robustness checks, and post hoc tests, providing a detailed examination of the relationships and insights derived from our analysis.

4.1 Main effects and interaction analysis

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation with the significance levels. The correlations of the variables in our model are well below the 0.7 threshold (Hair Jr. et al., 2010). We further addressed multicollinearity concerns by examining the variance inflation factors (VIF) and condition indexes. The highest VIF observed in the model equaled 1.97, and the highest value of the condition index equaled 25.65, both below the suggested thresholds (Hair Jr. et al., 2010).

To test the hypotheses, we apply a multi-model hierarchical linear regression procedure. The results of the linear regression are shown in Table 2.

The analysis employed a four-step hierarchical regression approach. In the base model, all control variables were included. Model 2 incorporated entrepreneurial legacy and model 3 OPCE in addition to the control variables. Finally, model 4 included an interaction term between entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE. Various tests were performed to assess regression assumptions to ensure the validity of the regression models. The significance of the R2 change was evaluated using an F test. Multicollinearity concerns were addressed by examining the variance inflation factors (VIFs), which were found to be below the suggested thresholds (VIFs < 1.17) in accordance with Hair et al., (2010).

Hypothesis 1 argues that the stronger the successors perceive the family’s entrepreneurial legacy, the greater the firm’s organizational ambidexterity will be. Model 2 supports Hypothesis 1, showing that the effect of entrepreneurial legacy is positive and significant (b = 1.25, p <.01). Hypothesis 2 suggests that OPCE fosters the firm’s organizational ambidexterity. In model 3, the effect of OPCE is positive and significant (b = 2.24, p <.01), lending support to Hypothesis 2. Model 4 includes the interaction effect between entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE. Hypothesis 3 suggests that the positive relationship between the entrepreneurial legacy and the firm’s organizational ambidexterity should strengthen in line with the extent to which successors are aware of their predecessors’ OPCE. The coefficient for this interaction effect is positive and significant (b =0.88, p <.05), thus supporting Hypothesis 3.

Figure 2 displays the interaction effect between entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE from model 4. We utilized the R-package developed by (Lüdecke, 2023) and plotted the interaction effect using the lower and upper bounds of OPCE. The figure illustrates that the firm’s organizational ambidexterity is nurtured more effectively through entrepreneurial legacy with increasing levels of OPCE.

4.2 Further robustness checks and post hoc tests

We measured organizational ambidexterity by multiplying exploration and exploitation. While this approach is the most applied method in extant research (Junni et al., 2013), alternative methods for calculating ambidexterity have also been reported in the literature. For instance, Lubatkin et al., (2006) measured ambidexterity by summing exploitation and exploration, while He & Wong, (2004) subtracted exploitation from exploration. However, combining the two measures into a single index may result in a loss of information. We conducted additional regression analyses to explore the interpretability of results obtained using the multiplication method. Specifically, we performed calculations by summing exploitation and exploration as well as by subtracting exploitation from exploration. The results obtained from the additive calculation were consistent with the multiplicative model of ambidexterity. However, the multiplied method demonstrated higher explanatory power (R2 = 0.185) compared to the additive model (R2 = 0.165). In contrast, the subtraction model exhibited much lower explanatory power (R2 = 0.028) than both the summation and multiplication models, which is in line with previous findings (e.g., Kammerlander et al., 2020). The results of the subtraction method do not support Hypothesis 3 (b = −0.06, p = 0.293).

Further, we examine whether farms from federal states where the Farm Inheritance Law is mandated differ from those without such a law. Farms that fall under the jurisdiction of this law typically exhibit certain characteristics, including a single-owning family and a minimum size that ensures the family’s livelihood. We created a dummy variable for federal states where the Farm Inheritance Law is mandatory. The results of the main effects are consistent with those obtained in our main analysis. Moreover, the created dummy variable was not significant in any of the regression models.

We also took into consideration the control variable “family cohesion,” which exhibited a high Cronbach’s alpha value. To assess its impact on the model, we ran additional analyses excluding this variable and found that the results remained similar to our initial model.

We also carried out post hoc tests using exploration and exploitation individually as the dependent variables. For exploitation, the results are consistent with those reported earlier. For exploration, the direct effects of entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE are significant, while the interaction effect between entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE was not significant. This is in line with our theoretical argument on the significant interactive effect of entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE on the balance between a family firm’s exploration and exploitation.

5 Discussion

The current research aimed to address how a family’s entrepreneurial legacy and entrepreneurial bridging during succession interact to influence organizational ambidexterity in family firms. Entrepreneurship that satisfies the current generation’s needs for the continuity of the existing business through exploitation while ensuring the exploration of environmental changes for the success of future generations is the deliberate outcome of family firm succession (Habbershon et al., 2010; Zellweger et al., 2012). Using a transgenerational entrepreneurship lens, we examined the successor’s awareness of the family’s entrepreneurial legacy and the successor’s perception of the predecessor’s provision of entrepreneurial resources. To this end, our results show that the interaction between successors’ entrepreneurial legacy and the predecessors’ OPCE is associated with the family firm’s increased organizational ambidexterity. Interestingly, post hoc tests revealed that most family farms can leverage high levels of entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE for exploitation but face challenges in combining entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE to facilitate exploration. These results suggest that while the perception of an entrepreneurial legacy and OPCE both promote exploitation, family firms’ balance between exploration and exploitation is mainly associated with the interaction between entrepreneurial legacy and the bridging of entrepreneurial resources through OPCE.

5.1 Theoretical implications

One of the study’s main contributions is to theorize on and empirically test the interactive relationship between entrepreneurial legacy (right seed) and predecessors’ provision of entrepreneurial resources during succession (fertile soil), also known as entrepreneurial bridging. Most previous research has assumed a consistency of entrepreneurial legacy perceptions across generations and has only offered explanations for family firms that successfully use their entrepreneurial legacy (e.g., Diaz-Moriana et al., 2020). While some studies emphasize differences between generations (e.g., Miller et al., 2003), implications on how divergence affects family firms’ succession process and performance are rare (Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2022; Sieger & Minola, 2017). We argue that divergence between the entrepreneurial mindset of successors (i.e., entrepreneurial legacy) and the predecessor’s provision of entrepreneurial resources in the bridging period of succession hinders transgenerational entrepreneurship. By examining different constellations of successors’ interpretation of the family firm’s entrepreneurial legacy and predecessors’ entrepreneurial bridging, we better understand how family firms transmit entrepreneurship across generations. We emphasize our conceptualization of different constellations by introducing the seed-soil metaphor. Seeds (i.e., entrepreneurial legacy) and soil (i.e., entrepreneurial bridging) unfold their full potential only in their interaction—that is, when the right seeds fall on fertile soil.

While previous literature on entrepreneurial legacy has been mainly conceptual (Hammond et al., 2016), we measure entrepreneurial legacy and empirically assess its association with organizational ambidexterity. Prior research on organizational ambidexterity and family firms has only briefly addressed the influence of entrepreneurial mindsets across generations (Lavie et al., 2010). The dearth of knowledge on the implications for organizational ambidexterity is surprising since a known challenge for family firms is their quest to reconcile tradition and innovation across generations (De Massis et al., 2016; Zellweger & Sieger, 2012). Furthermore, rebalancing a firm’s orientation likely occurs dynamically in family firms, enacted during succession processes (Dalpiaz et al., 2014; Diaz-Moriana et al., 2020). Hence, the transmission of mindsets and resources during succession might serve as a source for family firms’ ambidexterity (Goel & Jones, 2016). Against this background, our study extends current research on organizational ambidexterity by stating that transmitting the family’s entrepreneurial legacy through entrepreneurial resource provision (i.e., OPCE) strengthens the firm’s ability to pursue exploration and exploitation simultaneously. Furthermore, we contribute to the literature on transgenerational entrepreneurship by drawing on the empirically established OPCE construct to increase our theoretical understanding of the role of entrepreneurial resources in the bridging period of succession in family firms.

The framework of transgenerational entrepreneurship suggests that the entrepreneurial mindset of family members plays a crucial role in a firm’s entrepreneurial performance (Habbershon et al., 2010). Previous research has examined various aspects of predecessors’ entrepreneurial mindset that foster successors’ entrepreneurship, such as the provision of financial (Jansen et al., 2022) and non-financial resources (Riar et al., 2022) and support for intergenerational collaboration, for example, ensuring the successor’s authority in intergenerational decisions (Hauck & Prügl, 2015). Our study aims to expand upon this understanding by capturing the predecessor’s entrepreneurial mindset more holistically, evaluating how well they provide an organizational environment conducive to entrepreneurship. Despite being widely cited, Jaskiewicz et al., (2015) intriguing theoretical argument of “entrepreneurial bridging”—as a strategic activity of transgenerational entrepreneurship—has rarely been explored empirically. Building on the established OPCE construct allows us to cast light on the core idea of the predecessor’s provision of an organizational environment that supports entrepreneurship. Theoretically, we propose that these entrepreneurial environments during succession unlock the family firm’s ability to use its past while venturing into the future.

5.2 Limitations and future research

Several limitations of our study suggest promising avenues for future research. Although we followed academic rigor to adapt the scales to our context of multigenerational small family firms, a practice in line with many other family business studies, we acknowledge that further validation processes could enhance the validity of our variables. We incorporate the established OPCE scale to understand better the theoretical arguments of the bridging logic in family firms. However, this scale is designed to capture middle managers’ perception of an appropriate organizational context to facilitate entrepreneurship (Hornsby et al., 2013). While successors in small family firms accept responsibilities that are probably comparable to those of middle managers in larger organizations soon after joining the firm, future research might delve into how the provision of entrepreneurial resources across generations differs for large family firms.

Moreover, we assessed the successor’s perception of the family’s entrepreneurial legacy by extracting items from entrepreneurial legacy literature. This approach allowed us to gather rich empirical data on the family’s entrepreneurial legacy as perceived by the successor. However, the results from our CFA showed a borderline acceptable model fit. This outcome implies that our model items may not comprehensively represent the observed relationships. For example, instances of entrepreneurship and resilience are only one facet of the family legacy (Hammond et al., 2016). There might be further entrepreneurial artifacts family members interpret to create a meaning for entrepreneurship (Rutherford & Kuratko, 2016); however, that is yet to be empirically proven.

Second, our sample is restricted to small, multigenerational family farms. Entrepreneurship in the agricultural industry means something different compared to other industries (i.e., Pindado & Sánchez, 2017). Such differences might be visible in longer time horizons and family CEOs’ acceptance of investments to continue the entrepreneurial legacy that might result from their long-expected tenure (Zellweger, 2007). Further, the strong family influence in family farms depicts a special environment that likely shapes their entrepreneurial activities (Chua et al., 2012). We believe that such high family influence might enable successors to more effective leverage entrepreneurial bridging (i.e., Discua Cruz et al., 2013). Future research can contribute to this discussion by exploring potential antecedents of our model. One interesting avenue for future research would be to examine how different forms of education impact successors’ ability to leverage transgenerational entrepreneurship. Specifically, comparing successors who enter the firm immediately after university to those who have gained extensive external leadership experience could deepen our understanding of transgenerational entrepreneurship. While the former may have more time to embrace the family’s legacy, the latter might be better capable of leveraging the provided entrepreneurial resources.

Moreover, considering the importance of predecessors’ entrepreneurial bridging for successful organizational ambidexterity, future research could explore how predecessors’ capabilities can be harnessed post-transition. For instance, should predecessors maintain an active role and gradually reduce their involvement, or should they make a clean break and exit the firm to foster entrepreneurship? Furthermore, given the long history of many of the family farms in our sample, achieving organizational ambidexterity might be challenging due to path dependency (Sutherland et al., 2012). Succession is thus an apt period for breaking with the path. For example, the successor might foster the farm’s ambidexterity in its farming practices, such as switching production methods to conservation agriculture (i.e., minimal mechanical soil disturbance, biomass mulch soil cover, and crop species diversification) (Kassam et al., 2019) simultaneously to implementing technologies that improve the efficiency of such farming practices, such as through site-specific farming (i.e., optimizing output rate depending on within-field variability in yield potential) (Munnaf et al., 2020). In line with this, future research could explore the outcomes of such ambidextrous orientation for the firm’s longevity, such as by examining changes in firm performance.

While we controlled for size and variables characteristic of the agricultural industry, future research could provide a more detailed analysis of how the perception of entrepreneurial legacy in family firms of different sizes (i.e., micro-, small-, and medium-sized) and across different industries affects a firm’s ambidexterity. We believe that smaller firms can be strongly affected by their entrepreneurial legacy when the majority of the workforce are family members. In contrast, entrepreneurial legacy fades in larger firms when other factors (such as a formalized firm culture (Schein, 1990)) drive the organizational identity. In addition, although the ongoing structural change in the agricultural sector demands family firms strive for transgenerational entrepreneurship (Fitz-Koch et al., 2018), family firms in other, more competitive industries might be more sensitive to achieving organizational ambidexterity for their survival. Given that family firms operating in highly competitive industries can draw on a rich selection of past entrepreneurial activity that contributed to their survival, it is more feasible for those firms to flexibly adapt to environmental changes by exploiting the core business. Hence, we hope that scholars will be able to replicate our results in other, more competitive industries.

Finally, we are aware of the limitations of our cross-sectional study design that might weaken the results obtained from the data. Although the literature suggests that perceptions of the family’s legacy are likely to influence family members’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship and we employed several tests to reduce the risk of reverse causality, we do not completely rule out that organizational outcomes might also influence how family members perceive their family’s entrepreneurial legacy. To this end, there is an opportunity for future research to exploit the potential of the dynamics of bridging periods of succession by conducting longitudinal studies on entrepreneurial bridging.

5.3 Practical implications

Providing successors an environment to thrive during succession is one of the most challenging tasks for predecessors. Our results show that the predecessor’s provision of autonomy and resources enables an environment for successors to engage simultaneously in exploration and exploitation. Specifically, we find that when successors have a strong perception of the family’s entrepreneurial legacy, they are more likely to leverage the resources provided by the predecessor effectively. However, if successors lack this entrepreneurial mindset, they may perceive the resources as a “poisoned gift” and feel constrained by obligations to use them in a specific way. Additionally, when successors feel they lack resources provided by their predecessors, it can motivate them to emancipate from their predecessor’s expectations and make decisions that may not necessarily be aligned with the firm’s goals of simultaneously pursuing exploration and exploitation. These findings are also relevant for successors who wish to pass on their family business to their children. Our findings underscore the importance of preserving and promoting the family’s entrepreneurial legacy, as this helps to instill an entrepreneurial mindset in future generations. By sharing stories of past entrepreneurship and resilience within the family, successors can ensure their children’s shared understanding of entrepreneurship, which might nurture intergenerational collaborations in the future.

6 Conclusion

Although scholars of family firms acknowledge the importance of succession and transgenerational entrepreneurship, prior literature has scantly addressed the interplay of entrepreneurial mindsets and entrepreneurial resources on the family firm’s ability to achieve organizational ambidexterity. By applying a transgenerational entrepreneurship perspective on the succession process in multigenerational family farms, our analysis highlights the role of entrepreneurial legacy, allowing successors to reconcile exploration and exploitation. Second, we demonstrate that predecessors’ provision of entrepreneurial resources is a salient mechanism during succession that furthers a family firm’s organizational ambidexterity through transgenerational collaborations that navigate and complement successors’ entrepreneurship. Finally, we find that the interaction between the successor’s perception of the family’s entrepreneurial legacy and the predecessor’s provided entrepreneurial resources drives organizational ambidexterity in family firms. We emphasize this finding by introducing the seed-soil metaphor—transgenerational entrepreneurship can only prosper in family firms when the right seed falls on fertile soil. We hope that this research can help family firms to capitalize on their succession process by evoking their history and enabling transgenerational collaborations.

Notes

To ensure the sample was representative regarding geographic location, we randomly invited 176 farms located in Lower Saxony and ten farms located in Saarland by telephone to participate in the survey and, if they agreed, sent them an email-invitation with a link to the survey. These federal states only provide telephone numbers of vocational training farms and where otherwise not included in the sample.

We also run our regression model with the initial data set (N = 385). All results are consistent with those obtained with the reduced data set (N = 296).

References

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150783

Baessler, C., & Klotz, S. (2006). Effects of changes in agricultural land-use on landscape structure and arable weed vegetation over the last 50 years. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 115(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2005.12.007

Barbera, F., Stamm, I., & Dewitt, R.-L. (2018). The development of an entrepreneurial legacy: Exploring the role of anticipated futures in transgenerational entrepreneurship. Family Business Review, 31(3), 352–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486518780795

Batáry, P., Gallé, R., Riesch, F., Fischer, C., Dormann, C. F., Mußhoff, O., Császár, P., Fusaro, S., Gayer, C., Happe, A.-K., Kurucz, K., Molnár, D., Rösch, V., Wietzke, A., & Tscharntke, T. (2017). The former iron curtain still drives biodiversity–profit trade-offs in German agriculture. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1(9), 1279–1284. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0272-x

Bearden, W. O. (2006). A measure of long-term orientation: Development and validation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(3), 456–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070306286706

Benner, M. J., & Tushman, M. L. (2003). Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited. The Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 238–256. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040711

Bloom, B. L. (1985). A factor analysis of self-report measures of family functioning. Family Process, 24(2), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1985.00225.x

Cabrera-Suárez, K., De Saá-Pérez, P., & García-Almeida, D. (2001). The succession process from a resource- and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 14(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2001.00037.x

Cabrera-Suárez, M. K., García-Almeida, D. J., & De Saá-Pérez, P. (2018). A dynamic network model of the successor’s knowledge construction from the resource- and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 31(2), 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486518776867

Chirico, F., & Nordqvist, M. (2010). Dynamic capabilities and trans-generational value creation in family firms: The role of organizational culture. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 28(5), 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610370402

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Steier, L. P. (2011). Resilience of family firms: An introduction. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(6), 1107–1119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00493.x

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902300402

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., Steier, L. P., & Rau, S. B. (2012). Sources of heterogeneity in family firms: An introduction. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(6), 1103–1113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00540.x

Cirillo, A., Pennacchio, L., Carillo, M. R., & Romano, M. (2021). The antecedents of entrepreneurial risk-taking in private family firms: CEO seasons and contingency factors. Small Business Economics, 56(4), 1571–1590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00279-x

Clinton, E., McAdam, M., Gamble, J. R., & Brophy, M. (2020). Entrepreneurial learning: The transmitting and embedding of entrepreneurial behaviours within the transgenerational entrepreneurial family. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2020.1727088