Abstract

Divergent thinking is the ability to produce numerous and diverse responses to questions or tasks, and it is used as a predictor of creative achievement. It plays a significant role in the business organization’s innovation process and the recognition of new business opportunities. Drawing upon the cumulative process model of creativity in entrepreneurship, we hypothesize that divergent thinking has a lasting effect on post-launch entrepreneurial outcomes related to innovation and growth, but that this relation might not always be linear. Additionally, we hypothesize that domain-specific experience has a moderating role in this relation. We test our hypotheses based on a representative longitudinal sample of 457 German business founders, which we observe up until 40 months after start-up. We find strong relative effects for innovation and growth outcomes. For survival, we find conclusive evidence for non-linearities in the effects of divergent thinking. Additionally, we show that such effects are moderated by the type of domain-specific experience that entrepreneurs gathered pre-launch, as it shapes the individual’s ideational abilities to fit into more sophisticated strategies regarding entrepreneurial creative achievement. Our findings have relevant policy implications in characterizing and identifying business start-ups with growth and innovation potential, allowing a more efficient allocation of public and private funds.

Plain English Summary

Divergent thinking is the ability to generate many different and novel ideas to solve tasks. When facing a challenge or a problem, divergent thinkers would explore different approaches in an unsystematic fashion in order to solve it. It is known that this cognitive ability plays a role in the innovation process of firms. However, what is its role in the entrepreneurial process itself, particularly in the last post-launch phase, where entrepreneurs seek survival through innovation and growth? Is the relation between divergent thinking and business outcomes linear? Are there other factors that exacerbate its role? Accounting for a variety of factors that might influence business outcomes, we find that divergent thinking has a positive effect on innovation and business growth 40 months after start-up, as well as evidence of non-linearities with respect to business survival. Furthermore, we find domain-specific experience to moderate the effect of divergent thinking on business performance in the post-launch phase. These results make a valuable contribution to the understanding of creativity and business performance and for public and private investors to identify and foster businesses with innovative and growth potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Understanding which factors influence entrepreneurial development is crucial to the design of entrepreneurship public policies, as such interventions can influence entrepreneurial performance and overall the size of the entrepreneurial sector in the economy (Parker, 2018). This understanding is also valuable for investors (especially inexperienced ones), who might place weight on product attributes or founders’ motivation in their decision-making process, given the complex and technical investment information that they need to analyze (Shafi, 2021). There are different factors influencing entrepreneurial development. Macroeconomic conditions like GDP and unemployment rates influence entrepreneurship entry and exit rates (Koellinger & Thurik , 2012; Fritsch & Kritikos , 2016; Sedlacek & Sterk , 2017), and human capital contributes to exploiting new opportunities and accumulating relevant new knowledge, as well as facilitating finding financial resources (Unger et al. , 2011a; Marvel et al. , 2016). Likewise, creativity plays a significant role. Creativity and entrepreneurship are closely connected, as the exploration and exploitation of business opportunities require creative thinking (Zhou, 2008), and both concepts can be understood as processes (Lex & Gielnik, 2017). Creative achievement within an organization is the result of a combination of cognitive style (e.g., divergent thinking), personality (e.g., locus of control), motivation, domain-specific skills, and resources at different stages of the creative process (Amabile , 1988; Woodman et al. , 1993; Baer , 2012; Amabile & Pratt , 2016). Similarly, instead of considering entrepreneurship as an isolated event, it can be understood as a continuous process in which different factors are at play during three distinct phases, namely the pre-launch, launch, and post-launch of a business venture (Baron, 2007). According to Lex & Gielnik (2017), the predominance of the cognitive ability of divergent thinking in the creative process will fluctuate across the different phases of entrepreneurship. In the third phase, in particular, entrepreneurs will seek business survival through continuous innovation and growth (Lex & Gielnik, 2017). The aim of this paper is to analyze the role of divergent thinking in the post-launch phase of the entrepreneurial process by examining its relation with survival, innovation, and growth outcomes, as well as focusing on potential non-linearities in these relations and the potential moderating effect of types of domain-specific experience.

The concept of divergent thinking was first introduced by Guilford (1967), and it refers to the ability to generate diverse and numerous ideas to solve tasks. When facing a challenge, divergent thinkers consider different approaches that do not necessarily rely on previous knowledge or routines. Divergent thinkers explore different answers to a question in an unsystematic fashion, whereas convergent thinkers look for one correct answer in an analytical way. Moreover, even though it cannot be understood as creativity itself (Runco, 2008), divergent thinking is described as a psychometric measure of creative problem-solving abilities and an indicator of potential for creative thinking and future creative performance (Kuhn & Holling , 2009a; Runco & Acar , 2012). As divergent thinking abilities can be transferred to specific domains (Clapham et al. , 2005; Chen et al. , 2006), the channel through which divergent thinking influences entrepreneurial outcomes is the transfer of ideational abilities to a specific domain of business, whereby business owners use their divergent thinking skills to generate business ideas that enhance their performance (Gielnik et al., 2012).

Creativity is fundamental to the innovation process, as it helps to recognize new business opportunities or needs and generate ideas to tackle them (Amabile , 1988; Scott & Bruce , 1994; Fillis & Rentschler , 2010; Shane & Nicolaou , 2015; Castillo-Vergara et al. , 2018). Furthermore, creativity and creative problem-solving skills are relevant to organizations facing changing business environments. Small-scale firms and start-ups face scenarios that require quick and flexible responses, given their low financial capital basis and highly segmented markets (Rauch & Frese, 2000). The ability to respond to those complex challenges in an innovative fashion strongly depends on creativity or creative problem-solving skills, such as ideation (Basadur & Hausdorf, 1996). Williams (2004) argues that organizations require a divergent thinking approach to solve heuristic problems. Given that the solutions to those problems are unknown, an optimal decision-making process should involve identifying alternatives and a divergent search for possible answers. Entrepreneurs are confronted with those challenges in all three phases of the entrepreneurial process. In the post-launch, in particular, entrepreneurs’ main objective is to guarantee the survival of the business through continuous growth and innovation (Lex & Gielnik, 2017).

The relationship between creativity and entrepre-neurial performance has been tested empirically multiple times (Sarooghi et al., 2015). However, even though divergent thinking and creativity are closely connected, the relationship between divergent thinking and entrepreneurship might not be as straightforward. Higher levels of divergent thinking might involve paradoxes (Acar & Runco, 2015). The diversity of the ideas might lead entrepreneurs to think in opposites or find contradictions, which could hinder their performance. Similarly, when facing a problem, entrepreneurs with high divergent thinking might consider multiple creative solutions but find it difficult to choose which is the more efficient or optimal. Accordingly, it is relevant to question whether the relation between divergent thinking and entrepreneurial performance is always positive. Furthermore, creative ideas might not translate directly into creative achievement, as this requires other factors such as motivation and network abilities (Baer , 2012; Acar & Runco , 2019). Most theoretical models concerned with creativity and entrepreneurship highlight that creative achievement is a combination of not only cognitive styles (convergent and divergent thinking) but their interaction with motivation, experience, domain-specific skills, and entrepreneurial context (Woodman et al. , 1993; Vincent et al. , 2002; Amabile & Pratt , 2016; Lex & Gielnik , 2017).

Drawing upon the cumulative process model of creativity in entrepreneurship (Lex & Gielnik, 2017), we hypothesize that divergent thinking has a lasting effect on entrepreneurial outcomes up until 40 months after start-up and that this relation is not always linear: higher levels of divergent thinking might be counter-productive during a phase in which both divergent and convergent thinking are necessary. Additionally, from an interactionist perspective (Zhou , 2008; Gielnik et al. , 2012) in a post hoc analysis, we argue that experience acts as a moderating contextual factor of the effect of divergent thinking on entrepreneurial performance, as it endows entrepreneurs with a different cognitive framework that allows them to recognize business opportunities more efficiently, and it controls the individual’s ideational abilities to update and sophisticate strategies to achieve creativity in a specific working environment (Baron & Ensley , 2006; Agnoli et al. , 2019). We estimate the relation between divergent thinking with business survival, patents or trademark protection applications, job creation, business field expansions, and regional expansions, as well as with dynamic outcomes such as having hired employees in the last 20 months and the realization of business field expansion plans.

Considering all of the variables that are at play within the creative and entrepreneurial processes, we control for a comprehensive set of possible confounders including socio-demographic variables, human capital, intergenerational transmission, labor market history, local macroeconomic conditions, business-related characteristics, and other personality characteristics, like the Big Five and locus of control and cognition based on two numeracy tests and a memory test. Taking into account Lex and Gielnik’s (2017) suggestion, that a longitudinal approach should be considered to test the main assumptions of the model, our data set combines survey data with administrative data from the Federal Employment Agency in Germany. It comprises a unique representative longitudinal sample of 457 entrepreneurs who started their business in the first quarter of 2009 and were surveyed twice, 19 and 40 months after business formation. Based on the Runco Ideational Behavior Scale (RIBS) developed by Runco et al. (2001), we construct a divergent thinking measure using a six-item battery of statements and aggregating them by factor analysis into one divergent thinking factor index to estimate its influence on the mentioned outcomes. We follow Podsakoff et al. (2003) and solve potential common method biases by using a temporal separation of about 20 months between our divergent thinking measure and the outcomes of interest.

Our results show a long-term effect of divergent thinking on post-launch innovation and growth outcomes. An increase in divergent thinking translates into a higher probability of entrepreneurs applying for patents or trademark protection, having employees, exploring new business fields, and expanding into new regions 40 months after business foundation. Besides, an increase in divergent thinking increases the probability of hiring employees and realizing field expansion plans between the two interviews. The relative effects of divergent thinking on these outcomes are economically relevant and range from about 16 to 38% (for a one standard deviation increase) with respect to the mean. Additionally, we find strong evidence of non-linearities in the relation of divergent thinking with business survival. There is also evidence for non-linear effects of divergent thinking on exploratory innovations and job creation, as well as suggestive evidence for expansion outcomes. We show that the relation between divergent thinking and innovation outcomes is always positive (in line with previous literature Sarooghi et al. , 2015), with increasing marginal returns. Whereas, for job creation outcomes such as hiring or having employees, we show that the relation follows an inverse U-shape, indicating decreasing marginal returns. The results for other outcomes are partially inconclusive but suggestive of potential non-linearities. Finally, contributing to the interactionist perspective literature on the interplay of contextual factors with divergent thinking, we find that domain-specific experience from self-employment has a different interaction effect compared to experience from regular employment. While the latter positively affects the probability of business fields and regional expansions, the former hinders innovation and job creation. Thus, experience from regular employment is likely to follow Lex & Gielnik ’s (2017) logic in which divergent thinking affects entrepreneurs’ success through the opportunity identification, whereas experience from self-employment might put entrepreneurs in a functional fixedness mindset that hinders innovation.

Our study makes several contributions to the entre-preneurship literature. First, it provides new evidence on the link between divergent thinking and entrepreneurial performance by testing the theoretical framework on an ideal setting: we use the longitudinal nature of our data to test the effect of divergent thinking on post-launch entrepreneurial outcomes, namely, survival, innovation, and growth-related outcomes 40 months after business foundation. We show that divergent thinking has a long-term effect on innovation and growth entrepreneurial outcomes. This contributes to the creativity and entrepreneurship research stream, showing the relevance of divergent thinking as a significant explanatory variable for business success in yet another context. This understanding might facilitate the design of entrepreneurial training programs and allow public and private investors to characterize or identify businesses with growth and innovation potential at early stages. Second, we provide new evidence on the non-linearity of divergent thinking in relation with survival, innovation, and job creation outcomes in the third phase of entrepreneurship, as well as suggestive evidence of potential non-linearities in relation with expansion outcomes. This could spur a discussion on the optimal amount of divergent thinking in the post-launch phase. Third, it provides new empirical evidence of the role of domain-specific experience as a contextual factor and shows that there are different interaction effects according to the type of experience gathered prior to business foundation. We show that experience from regular employment has a different interaction effect compared to experience from self-employment.

2 Theory and hypotheses development

2.1 Divergent thinking

Divergent thinking is defined as the ability to produce diverse and numerous responses to questions or tasks. It is also a reliable indicator of the potential for creative thinking, as it often leads to originality, which is the central feature of creativity. Although the assessment of divergent thinking has dominated the creativity research to the point that some might use it as a direct measure of creativity, divergent thinking is only an underlying factor of the creative process (Vincent et al. , 2002; Kuhn & Holling , 2009a; Runco & Acar , 2012). Creative performance or creative achievement is a combination of both divergent and convergent thinking, as it is the result of an unrestricted search of ideas (divergent thinking) and their evaluation (convergent thinking) to perform a task or solve a problem (Brophy , 2001; Cropley , 2006; Runco , 2010).

Divergent thinking is also expected to be stable across time. According to McCrae et al. (1987), individual differences in divergent thinking are stable over a 6-year window. Although there is a decline after the age of 40 (except for ideational fluency, namely the number of ideas generated), individuals with high levels of divergent thinking are likely to maintain high levels relative to similar-age peers and in absolute terms. Additionally, more recent studies show that there are no significant differences between age groups, declines in divergent thinking scores are not age-related, and—regardless of an expected cognitive decline—divergent thinking can be preserved in elderly ages (Roskos-Ewoldsen et al. , 2008; Palmiero et al. , 2014; 2017).

There are several divergent thinking tests.Footnote 1 Unlike classical intelligence tests—which might fail to distinguish between creative and non-creative individuals (Kim , 2008; Hass , 2015)—divergent thinking tests often involve open-ended questions with no correct answers, and individuals are asked to provide as many original responses as possible. Runco et al. (2001) argue that this type of tests and their results are conditioned by the experimental setting (timing, number of people in the room, provided information, etc.) in which the tests are implemented and the subjective assessment of the answers by the evaluators, and therefore, the creative achievement or performance on such experiments might be driven by different factors other than divergent thinking. The authors developed the RIBS to describe actual overt behavior in terms of ideation, which they claim to be the most relevant criterion when studying the predictive validity of divergent thinking tests. We rely on the validity of this scale to measure divergent thinking in our sample.

2.2 Divergent thinking and entrepreneurship

The role of divergent thinking in entrepreneurship can be analyzed through the lens of creativity. Creativity is an indispensable component of entrepreneurship, as it promotes identifying business opportunities, as well as generating ideas for new products, services, or processes (Zhou, 2008). Creativity and—most importantly—creative achievement are the results of combining different components within a creative process. Organizational creativity is an intersection of a creative process,Footnote 2 creative person, creative product, and creative situation (Woodman et al., 1993). At the individual level, creativity is the result of experience (e.g., biographical variables), cognitive style (e.g., divergent thinking), personality (e.g., self-esteem), relevant knowledge, motivation, and social and contextual influences (e.g., social facilitation or time constraints, Woodman et al. (1993)). These components are combined at different stages of the creative process, as Amabile (1988) and Amabile and Pratt (2016) describe. Amabile (1988) developed a model of organizational creativity and innovation based on the premises that individual creativity feeds innovation within organizations, and domain-relevant skills like knowledge, talent, or technical skills are not sufficient for an individual to produce creative work. Amabile and Pratt (2016) present an updated version of this model, which focuses on the individual-level psychological process involved in creativity. According to their model, the individual creative process is influenced by skills in creative thinking, besides motivation and domain-specific skills. Assuming that an individual has skills and incentives to engage in creative performance, the authors argue that a cognitive style that enhances taking new perspectives on problems is a fundamental skill in the production of creative work, as it combines the former two raw materials in new ways to generate innovative products. Ultimately, this cognitive factor will be a combination of both divergent and convergent thinking, as diverse and original ideas need to be explored but also assessed and evaluated at some point during the process (Brophy , 2001; Cropley , 2006; Runco , 2010).

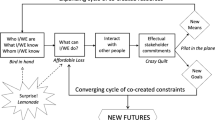

Like creativity, entrepreneurship can also be understood as a process. Instead of considering it an isolated event or a sequence of isolated events, entrepreneurship can be described as a continuous, evolving process (Baron , 2007). Lex and Gielnik (2017) argue that in order to understand the relationship between creativity and entrepreneurship, it is necessary to consider their nature as processes comprising different components and phases. Thus, they develop the cumulative process model of creativity in entrepreneurship. As theorized by Baron (2007), the entrepreneurship process has three major phases, namely the pre-launch, the launch, and the post-launch of a business venture. In each phase, different outcomes have predominance, and the relative importance of some variables might fluctuate (Shane , 2003; Baron , 2007). Lex and Gielnik (2017) disentangle creativity into divergent and convergent thinking and argue that both are at play during the three entrepreneurial phases. However, the relative importance or predominance of each cognitive style depends on the phase in which entrepreneurs find themselves.

The first phase of the entrepreneurial process is the pre-launch. This phase is characterized by the exploration and identification of viable business opportunities (Ardichvili et al. , 2003; Baron , 2007; Dimov , 2007). At this stage, in order to generate a high number of novel and original business ideas, divergent thinking must have predominance over convergent thinking (Lex & Gielnik, 2017). In turn, convergent thinking plays a role in assessing the viability of those ideas (Cropley, 2006). However, while both styles are necessary at this stage, divergent thinking should play the major role (Gielnik et al. , 2014; Lex & Gielnik , 2017), given that the process of identifying business opportunities is vital at a pre-launch stage, and this process strongly depends on creating novel combinations of ideas (Eckhardt & Shane , 2003; Gielnik et al. , 2014). On the other hand, the second phase of the entrepreneurial process—the business launch—challenges entrepreneurs’ capacities for planning, assembling financial resources, building and leveraging from social networking and human capital, etc. (Madsen et al. , 2003; Shane & Delmar , 2004; Baron , 2007; Lange et al. , 2007; Unger et al. , 2011b; Lex & Gielnik , 2017). At this stage, entrepreneurs once again require both divergent and convergent thinking. For instance, they need to generate novel and attractive ideas to appeal potential investors and persuade them during negotiations (Ward , 2004; Chen et al. , 2009; Lex & Gielnik , 2017), whereby coming up with those ideas would require a divergent thinking style (Cropley, 2006). Meanwhile, entrepreneurs need to design a business plan for their new venture (Baron , 2007; Honig & Samuelsson , 2014). Evidence shows that business planning has an influence on venture creation and development (Delmar & Shane , 2003; 2004; Honig & Samuelsson , 2014). This task involves a rigorous search and evaluation of relevant information (Chen et al. , 2009; Honig & Samuelsson , 2014), which requires entrepreneurs to use a convergent thinking cognitive style (Cropley, 2006). Overall, at the second stage of the entrepreneurship process, entrepreneurs will require more convergent thinking, as they need to focus on the opportunity that they chose in the previous phase to make it viable and feasible (Lex & Gielnik, 2017).

2.3 Deriving our hypotheses

2.3.1 Divergent thinking in the post-launch phase

The main focus of this study is the third phase of the entrepreneurship process, namely the post-launch, which entrepreneurs enter 12 to 18 months after start-up (Baron, 2007). In this phase, entrepreneurs need to secure business survival, i.e., guaranteeing the new venture is a viable, lasting, and growing business (Lex & Gielnik, 2017). For this purpose, entrepreneurs need to guarantee continuous innovation and growth in the form of creating new products, services, or processes; conducting negotiations; attracting and retaining high-quality workers; and developing strategies for promoting, among others (Baron , 2007; Lex & Gielnik , 2017). Those activities require both divergent and convergent thinking.

There are two types of innovations that require different levels of divergent and convergent thinking, namely exploratory and exploitative innovations. Exploratory innovations—also known as radical inno-vations—refer to the inclusion of completely new products, services, or processes, particularly designed to meet the needs of potential new costumers (Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008). This type of innovation focuses on originality and novelty and refrains from relying on existing knowledge (Benner & Tushman , 2003; Jansen et al. , 2006). By contrast, exploitative or incremental innovations refer to changes that aim to extend or improve existing processes, products, or services and therefore rely on existing knowledge to build upon. They are designed to meet the needs of existing clients (Raisch & Birkinshaw , 2008; Jansen et al. , 2006). Thus, divergent thinking plays a more relevant role in generating exploratory innovations, and convergent thinking is more suitable for exploitative ones (Lex & Gielnik, 2017).

In terms of growth, when it comes to job creation, entrepreneurs need to use divergent thinking to develop novel and creative working environments that attract high-quality workers, allow them to exploit their creativity, and keep them motivated (Williams , 2004; Matthew , 2009). However, at the same time, those working environments need to be stable, with well-defined standard operating procedures, for which entrepreneurs need to use a convergent thinking cognitive style (Lex & Gielnik, 2017). When it comes to other types of growth such as dabbling in new business fields or expanding the business into new areas or regions, entrepreneurs’ divergent thinking helps them to develop alertness to new ideas and information (Tang et al. , 2012; Gielnik et al. , 2014). Higher alertness increases the likelihood of identifying business opportunities (Ardichvili et al., 2003). Furthermore, the process of business and regional expansions requires assessing those potentially useful new business opportunities, negotiation skills, and planning, for which entrepreneurs require convergent thinking.

Empirical evidence shows that there is a positive relation between creativity and innovation outcomes, although the strength of the relationship depends on contextual factors (Sarooghi et al., 2015). Likewise, evidence suggests that a firm’s innovativeness has a significant relation with the venture’s growth (Roper , 1997; Thornhill , 2006; Audretsch et al. , 2014). When looking at divergent thinking specifically, Ames and Runco (2005) show the positive correlation between divergent thinking (measured as ideational behavior using the RIBS) and the number of businesses that the entrepreneurs have started. Additionally, Gielnik et al. (2012) show that divergent thinking influences entrepreneurship growth through business idea generation, under the assumption that divergent thinking is a general cognitive ability that can be applied to specific domains (Clapham et al. , 2005; Chen et al. , 2006; Baer , 2010).Footnote 3 Overall, several scholars have focused on the effect of creativity and/or divergent thinking on entrepreneurial outcomes (see inter alia Vincent et al. , 2002; Ames & Runco , 2005; Gielnik et al. , 2012; Gielnik et al. , 2014; Reid et al. , 2014; Chen et al. , 2015). However, as Lex and Gielnik (2017) point out, very few have analyzed this relationship specifically for the post-launch phase, and evidence is mixed as the effects are not always significant. For instance, Baron and Tang (2011) find a significant positive effect of creativity on the implementation of radical innovativeness, and Morris and Fargher (1974) and Ames and Runco (2005) find a positive effect on venture growth, whereas Heunks (1998) finds no significant effect on venture profit growth. As Lex and Gielnik (2017) suggest, in order to adequately test the main assumption of the model, a longitudinal approach should be considered, as the role of divergent thinking might fluctuate over time. In addition to the rather mixed evidence available so far, little is known about the long-term effect of divergent thinking on entrepreneurial outcomes. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

-

H1a:

Divergent thinking has a positive long-term effect on business survival in the post-launch phase.

-

H1b:

Divergent thinking has a positive long-term effect on exploratory innovation outcomes in the post-launch phase.

-

H1c:

Divergent thinking has a positive long-term effect on entrepreneurial growth outcomes in the post-launch phase.

2.3.2 Divergent thinking non-linearities

As already mentioned, in the post-launch phase, entre-preneurs are not expected to place more emphasis on one of the two cognitive styles, but rather combine them to be innovative and grow their business. However, it is possible that entrepreneurs with higher levels of divergent thinking may give more relevance to it and thus hinder their performance. While divergent thinking is implicitly assumed to have a linear and positive relation to creative and entrepreneurial performance in theoretical models (Amabile & Pratt , 2016; Lex & Gielnik , 2017), studies suggest that this relationship might not always be the case, especially when it comes to innovation.

Although innovativeness facilitates the design of organizational routines, the discovery of new approaches to technologies and processes, and the ability of firms to adapt to changing market conditions, evidence shows that may not always be beneficial for small and medium-sized firms’ performance (Rosenbusch et al., 2011). For example, fostering an innovative orientation has more positive effects on overall performance than actually investing in creating innovation process outcomes like patents (Rosenbusch et al., 2011). In turn, Kreiser et al. (2013) have shown that the relation between innovation and performance follows a U-shape. However, the attempts to address non-linearities do not focus on divergent thinking but rather on outcomes of it (e.g., innovation). The theory and current evidence have not addressed the question of whether the relation between divergent thinking and entrepreneurial outcomes is always linear, let alone its potential non-linearities in the third phase of entrepreneurship. It is known that divergent thinkers might encounter contradictions and paradoxes, as they allow their minds to go in different directions and explore potentially opposing ideas at the same time (Acar & Runco, 2015), which can result in difficulties in prioritizing and executing ideas, as well as difficulties in decision-making (Malhotra & Harrison, 2022). Exploring different perspectives and alternatives to make decisions requires a substantial investment of time and energy (Bartunek et al., 1983), and it has been shown that it reduces performance in simple contexts and under constrained conditions (Malhotra & Harrison, 2022). We argue that even though the relation of divergent thinking with innovation and growth is positive, this relation is not necessarily linear, especially in the third phase of the cumulative process model, where both convergent and divergent thinking are at play. We therefore hypothesize the following:

-

H2:

The relationship between divergent thinking and entrepreneurial outcomes in the post-launch phase of entrepreneurship is not linear, as it might be negative for very high levels of divergent thinking.

3 Data and measures

3.1 Data creation

The data set that we use was initially collected by Caliendo et al. (2015, 2020). The authors created a unique data set that enables a comprehensive and in-depth comparison between subsidized start-ups out of unemployment and non-subsidized start-ups out of non-unemployment in Germany. As previously existing datasets usually did not provide sufficient information to clearly identify both groups and were somewhat restricted with respect to individual information about the founder (such as human capital or intergenerational transmission) and longitudinal information on business development, Caliendo et al. (2015) created a new dataset allowing for such a comparison. They drew representative random samples of founders who started a full-time business in the first quarter of 2009. The cohort comprises initially unemployed individuals who received a start-up subsidy (Gründungszuschuss) from the Federal Employment Agency,Footnote 4 and business founders who were not unemployed directly prior to start-up and did not receive the subsidy. Different data sources were used to create representative samples of both groups. Subsidized start-ups out of unemployment were registered at the Federal Employment Agency and hence could be easily identified in the administrative data (Integrated Employment Biographies) provided by the Institute for Employment Research (IAB). However, identifying the non-subsidized start-ups was not straightforward, mainly due to the absence of a centralized register for all business founders in Germany. Hence, Caliendo et al. (2015) relied on three different data sources to obtain contact information for non-subsidized start-ups: (1) the Chambers of Industry and Commerce (“Industrie- und Handelskammern,” CCI), (2) the Chambers of Crafts (“Handwerkskammern,” CC), and (3) a private address provider to ensure occupational representativeness. Finally, the authors extracted a random sample of business start-ups within the first quarter of 2009 from each data source and collected the required information on these businesses by means of computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATIs).Footnote 5

The business founders were surveyed twice. The first interview (wave 1) was conducted in 2010 around 19 months after start-up and focused on an extensive list of start-up characteristics, socio-demographics, previous labor market experiences, and intergenerational transmissions. Additionally to their labor market status, and conditional on the ongoing business activity of their initial start-up from the first quarter in 2009, they were also interviewed about their business performance across various dimensions, including the number of jobs created as well as innovation and expansion activities. The interviews conducted lasted on average 43 min. The total number of realized interviews was \(N=3835\), among which roughly 37% of interviewees were female, which is very close to the share of female founders in the general population of entrepreneurs in Germany (41% in 2009, Federal Statistical Office of Germany 2018). Caliendo et al. (2015) show that male subsidized founders significantly lag behind regular founders in terms of income, business growth, and innovation. Caliendo et al. (2020) amended the data with a second interview in 2012 (wave 2) that extends the observation window to 40 months after start-up for 2034 panel observations. They show that the gaps in the mentioned outcomes are relatively constant or even widening over time. Figure 3 clarifies the data structure.

3.2 Estimation sample

Even though the data was initially collected to evaluate the effects of the start-up subsidy and hence start-ups out of unemployment are somehow over-represented, it is an ideal data set for analyzing the performance of business start-ups in Germany as it contains a large set of informative covariates (see, e.g., Caliendo et al. (2023a, b)) and a broad spectrum of outcomes. While Caliendo et al. (2015, 2020) focused on a comparison between subsidized and regular founders, we follow a completely different avenue of research. We use a random sub-sample of the data for which the question on divergent thinking was elicited during the first interview. Additionally to the information from Caliendo et al. (2015, 2020), a random sub-sample of 1038 entrepreneurs from the first wave of interviews (about 25% of the sample) was asked a questionnaire module on cognitive and non-cognitive skills. The purpose of this sub-sample was to gather information on variables such as personality traits, numeracy skills, and memory, among others. We were able to include a battery of ideational behavior items related to divergent thinking in this module. The scale will be described in more detail in the next sub-section. The same module was given to an additional random sub-sample of 25% in the second wave as well.

We restrict our estimation sample to those entrepre-neurs who were surveyed twice, 19 months (wave 1) and 40 months after start-up (wave 2), who completed the module on cognitive and non-cognitive skills in the first wave of the survey and report the outcomes of interest 40 months after start-up in the second wave. Thus, we avoid potential reverse causality, as entrepreneurial performance might influence divergent thinking, introducing bias in our estimates. This leaves us with a final estimation sample of \(N=457\) business founders. Since we use longitudinal data, response attrition induces a (very) weak selective bias in our outcome variables. Entrepreneurs participating in both waves might select themselves into the sample. As it turns out, respondents of the two waves are on average older, with a higher education and professional background; they have had shorter unemployment spells and higher earnings in the past compared to the full sample from wave 1. We follow Caliendo et al. (2020) to correct the potential attrition bias in our sample by using an inverse probability weighting. Through the weighting procedure, almost all significant differences are eliminated.Footnote 6

3.3 Measures

3.3.1 Divergent thinking

The RIBS comprises different items that reflect overt ideational behavior. Given the budget constraints, the limited interview time, and the length of the questionnaires, the divergent thinking battery included in the module mentioned above was a shortened version of the RIBS in Runco et al. (2001). Individuals in our sample were asked to rate six items from the RIBS, with a focus on the frequency of ideation, attitudes towards ideation, and problem-solving ideation, which are in general the most relevant aspects of divergent thinking tests (Acar & Runco, 2019). This is not uncommon, as—for example—Stuhlfaut and Windels (2015) and Taylor et al. (2021) use the same number of items for their analysis. The items were rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree, and they are reported in Table 1. Items 1 (“I have many unusual ideas”) and 2 (“I think about ideas more often than most people”) relate to the frequency of ideation, items 3 (“I often get excited about my own ideas”) and 5 (“I like to think about new ideas just for fun”) reflect the attitudes of the entrepreneurs towards ideation, and items 4 (“I often have suggestions or ideas for solving problems”) and 6 (“Friends often ask me to help them find ideas or suggest solutions”) relate to ideation in problem-solving contexts.

We conduct a factor analysis to assess whether there are underlying factors that might explain the variance of the items as well as their correlation, thus avoiding the disadvantages of using a mean index, i.e., the simple average over all items.Footnote 7 Figure 4 in the Appendix shows the scree plot of eigenvalues and the loadings from the factor analysis. According to Fig. 4(a), retaining the first factor is sufficient to explain most of the variance of the six items, since the eigenvalue of the first factor is the only one larger than 1 and it is also the only one above the first pronounced break of the line. Columns 3 to 5 in Table 1 present the rotated factor loadings and uniqueness of the items. As shown in Fig. 4(b) and Table 1, all items load predominantly on factor 1, and the loadings are larger than 0.5, showing the strong correlation between the items and the factor. Furthermore, the first factor manages to explain the variance of all six items, as the uniqueness of the items is lower than 0.7. Here, the retained factor shows a stronger correlation with ideation frequency items (1 and 2) and less so with the problem-solving items (4 and 6). Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the items is 0.85.

We then extract a single factor as a divergent thinking factor index. This index describes the common variance of the items and relies on the data to determine each item’s weight in the overall index. Figure 1 shows the histogram and distribution of the standardized factor index and—as a comparison—the standardized mean index (which we get by simply using the mean values of each item). Both distributions are negatively skewed with a slightly long tail at the left-hand side of the distribution, which shows a predominant high divergent thinking level among entrepreneurs (the top of the distribution concentrates more than half of the density). We can see that the computed factor index gives a reliable representation of the data that is not far from the mean computation, with the advantage of giving a data-driven weighting to each item of the scale.

3.3.2 Outcome variables

We consider three types of self-reported outcome variables taken from the second wave: (i) survival, (ii) innovation, and (iii) growth-oriented variables.

Survival Survival is measured as an indicator variable that takes the value one when the entrepreneur was still self-employed with the same venture that they founded in 2009.Footnote 8

Innovation For exploratory innovation activities, we use the information concerning whether founders have filed at least one patent application or applied for trademark protection since start-up (1 if yes, 0 otherwise).Footnote 9

Growth outcomes With respect to growth-oriented outcomes, we consider the dimensions of job creation and expansion activities. For job creation, we consider the extensive margin, i.e., an indicator for businesses with at least one employee (1 if at least one employee, 0 otherwise), as well as an indicator for businesses that hired employees between the two waves of the survey (1 if hired employees, 0 otherwise). For expansion activities, we observe whether businesses expanded into new business fields or new regions (1 if yes, 0 otherwise) and whether they realized field expansion plans during the time between the two waves (1 if yes, 0 otherwise). This last variable was created by looking at entrepreneurs who stated that they planned to expand their business in wave 1 and reported expansion in wave 2. Table 4 (panel A) in the Appendix presents the outcomes of interest 40 months after business formation, while Table 5 shows the correlations among outcomes.

3.3.3 Control variables

There are several determinant factors of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship performance, both pecuniary and non-pecuniary (Parker, 2018). Given that our research aims to identify the influence of divergent thinking on entrepreneurial performance in the post-launch phase, it is necessary to control for other individual- and business-related variables that are known to affect entrepreneurial outcomes (Shane et al., 2003). Besides, in line with Lex and Gielnik (2017), we include a broad set of covariates that account for variables at different stages of the entrepreneurial process.

Personal characteristics These include age, gender, whether there are children in the household, and marital status. There is evidence supporting the consideration of these variables as controls in our analysis. For instance, Kautonen et al. (2014) show how age has an influence on entrepreneurial behaviors, measured as the starting or willingness to start a business. Similarly, Fairlie and Robb (2009) describe how female-owned firms have on average less start-up capital and experience and how this is reflected in performance. Additionally, the interplay between marital status and children has also been shown to be a determinant of entrepreneurial performance (DeMartino & Barbato, 2003).

Human capital We include a categorized version of entrepreneurs’ completed education level, as evidence shows that there is a significant relation between human capital and entrepreneurial success (Unger et al. , 2011b; Marvel et al. , 2016).

Intergenerational transmission This set of control variables comprises indicators regarding whether the parents were born abroad and were or are self-employed, whether the father was employed at the age of 15, and whether the entrepreneurs have taken over the business from their parents. These controls account for the importance of intergenerational transmission in entrepreneurial outcomes, as described by Dunn and Holtz-Eakin (2000). Evidence shows that entrepreneurs who take over their business from their parents leverage on social capital resources of their family-firm parents to guarantee business survival (Criaco et al., 2021).

Labor market history This set of covariates contains information on the duration of dependent employment right before start-up, overall unemployment and employment experience before start-up, as well as income from the last dependent employment. We include these variables as controls taking into account that the duration of former paid employment (Parker, 2018) and income from it influence entrepreneurial entry (Parker , 2018; Astebro & Chen , 2014).

Local macroeconomic conditions As business performance is closely connected with the business cycle (Millan et al. , 2012; Koellinger & Thurik , 2012; Sedlacek & Sterk , 2017), we include the number of vacancies available in relation to the stock of unemployment, the real GDP per capita in 2008 before start-up, and whether they live in East or West Germany.

Business-related characteristics This section of control variables includes the industrial sector of the business, whether its foundation was subsidized, and capital invested at start-up. Additionally, our data accounts for detailed information regarding entrepreneurs’ preparations before start-up and a categorical variable of industry-specific experience that allows us to determine whether entrepreneurs have gathered domain-specific experience from regular paid employment or former self-employment. As shown by Caliendo et al. (2015), formerly subsidized founders lag behind not only in survival and job creation, but especially also in innovation activities. Likewise, there is supportive evidence of the importance of financial capital invested for entrepreneurial performance (Holtz-Eakin et al. , 1994; Blanchflower & Oswald , 1998), as well as preparation and information gathering (Westhead et al. , 2009; Honig & Samuelsson , 2014; Delmar & Shane , 2003, 2004), and domain-specific experience, whether it is from self-employment (Jovanovic , 1982; Ucbasaran et al. , 2003; Cassar , 2014; Rocha et al. , 2015), or regular employment (Dunkelberg et al. , 1987; Parker , 2018).

Personality traits and cognition It has been shown that personality traits have a significant influence on business survival and other entrepreneurial outcomes (see, e.g., Rauch & Frese , 2007; Kroeck et al. , 2010; Zhao et al. , 2010; Caliendo et al. , 2010, 2014). On the other hand, divergent thinking is also closely connected with personality traits. Chamorro-Premuzic and Reichenbacher (1987) provide evidence that divergent thinking is correlated with openness to experience. Likewise, Chamorro-Premuzic and Reichenbacher (2008) show that divergent thinking has a significant positive relation with openness to experience and extraversion. In terms of cognition, we use numeracy and memory tests to account for this cognitive style, as it is mainly oriented to deriving one single correct answer, emphasizes accuracy and logic, and is intimately related to knowledge (Cropley, 2006). Overall, this set of covariates contains information on the Big Five personality traits, locus of control, and risk aversion, as well as numerical cognition and memory tests as proxies for convergent thinking.

The full list of control variables is listed in panel B of Table 4 in the Appendix, and Table B.1 shows the correlations among them.

3.3.4 Common method bias

Following Podsakoff’s (2003) recommendations, we exploit the longitudinal nature of our data set and rely on the temporal separation of measurement to tackle potential common method biases. The measure of divergent thinking and all control variables is taken about 20 months apart from the measure of the outcomes of interest. Additionally, our control variables come from two independent data sources and are partly self-reported and based on administrative information.

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Descriptives

Table 4 in the Appendix shows that the founders in our sample were on average 43 years old at the time of the start-up, about 36% are female, about 62% did not have children living in the household, and they are mostly from West Germany (about 80%). Most of them attended upper secondary school (43%) and have experience in the field in which they opened their business, mainly from former dependent employment (65%). Their business fields are mainly related to services (32%), manufacturing (16%), and retail sectors (17%). The upper part of Table 4 shows all outcome variables 40 months after businesses were started. Overall, we observe that nearly two-thirds of the businesses are still operating at the end of our observation period. Nearly half (47%) of them have at least one employee by that time and 39% hired employees in between the first (after 19 months) and second wave (after 40 months). Thirteen percent expanded into new regions and 27% into new fields (where 21% realized a field expansion plan by \(t_{40}\) that they had stated in \(t_{19}\)). Most interestingly with respect to our innovation outcome, 12% of the businesses filed an application for a patent or trademark.Footnote 10

4.2 Estimation strategy

In order to test the influence of divergent thinking on post-launch entrepreneurial outcomes, we estimate logit regressions for all binary outcome variables with different specifications of divergent thinking (linear and quadratic).Footnote 11 As described in Section 3.3.3, we control for an extensive set of individual socio-demographic and business-related characteristics, local macroeconomic conditions, and other personality traits and characteristics that are shown to influence entrepreneurial development and might be confounders driving the differences in outcomes between entrepreneurs with different levels of divergent thinking. The following logit regression for patents and trademark protection is exemplary for all outcome variables. The probability of applying for patents or trademark protection is described as a function of divergent thinking and other covariates:

where \(\text {DT}_i\) is operationalized based on the factor analysis described in Section 3.3.1, and \(\mathbf {X_{i}}\) stands for the vector of control variables described in Section 3.3.3. In order to capture possible non-linearities, we use divergent thinking as a continuous variable in a linear specification first to test hypotheses H1a–c and then add it in quadratic form to test hypothesis H2.

Additionally, in order to test the interaction effect of experience (hypothesis H3), we estimate the following regression using patents and trademark protection as an example:

where \(exper_i\) is an indicator of having domain-specific experience. We differentiate between experience from self-employment and from regular employment. All control variables used in Eq. 1 are included in \(\mathbf {X'}_i\) for Eq. 2.

4.3 Main results

4.3.1 Hypothesis 1

Table 2 shows the relation between divergent thinking and post-launch entrepreneurial outcomes. Estimates are shown in terms of marginal effects at the mean from logit estimations for panel A (linear specification) and logit coefficients for panel B (quadratic specification).Footnote 12 In panel A, column 2 shows support for our first hypothesis regarding exploratory innovation. An increase of one standard deviation (SD = 0.91) in the divergent thinking factorFootnote 13 is associated with an increase of 4.1 percentage points (marginal effect, \(b=0.041\), \(p<0.1\)) in the probability of applying for patents or trademark protection, which represents a relative effect of 34% in relation to the mean.Footnote 14 This confirms our hypothesis H1b, namely that divergent thinking has a positive influence on exploratory innovation outcomes in the post-launch phase 40 months after start-up.

Likewise, we find support for hypothesis H1c, tested by estimations columns 3 to 7 of panel A. Overall, divergent thinking has a positive effect on entrepreneurial growth in the post-launch phase 40 months after business foundation. An increase of one standard deviation in the divergent thinking factor is associated with an increase of 9.5 percentage points (p.p.) in the probability of having employees (\(b= 0.095\), \(p<0.01\)), 4.8 p.p. in the probability of expanding into new business fields (\(b=0.048\), \(p<0.1\)), 4.9. p.p. in the probability of expanding into new regions (\(b=0.049\), \(p<0.05\)), 6.5 p.p. in the probability of having had hired employees between \(t_{19}\) and \(t_40\) (\(b=0.65\), \(p<0.05\)), and 4.2 p.p. in the realization of field expansion plans (\(b=0.042\), \(p<0.1\)). The relative effect of divergent thinking on these outcomes ranges from about 16 to 38% with respect to the mean. The only variable for which we do not observe significant effects of divergent thinking in the linear specification is business survival. Given that there is no evidence of divergent thinking affecting the probability of business survival in the post-launch phase 40 months after start-up (\(b=-0.005\), \(p=0.819\)), we cannot confirm hypothesis H1a in the linear specification.

4.3.2 Hypothesis 2

We test hypothesis H2 using the quadratic form of the divergent thinking factor as an additional explanatory variable. Panel B of Table 2 reports logit coefficients for the linear and squared divergent thinking factors. The results show a positive and significant role of squared divergent thinking for patents and trademark protection applications (logit coefficient, \(\beta _2=0.724\), \(p<0.1\)), which suggests that the relation between divergent thinking and exploratory innovation in the post-launch phase might not be fully linear, but innovation is always higher, the higher divergent thinking levels are. We find similar results for survival in terms of squared divergent thinking (\(\beta _2=0.405\), \(p<0.01\)), albeit not in its linear form (\(p>0.1\)). On the other hand, the relation between divergent thinking and the probability of having employees describes an inverse U-shape (\(\beta _1=0.529\), \(p<0.05\); \(\beta _2=-0.354\), \(p<0.05\)), suggesting that the positive effect of divergent thinking on such outcome starts decreasing after a certain point.

However, this evidence is not completely informative by itself. In this case, our variables of interest—i.e., divergent thinking in linear and quadratic form—are highly correlated, and therefore, we conduct a series of tests to validate their joint significance and the necessity of including divergent thinking in a quadratic form. First, we test for joint significance using the Wald test and find support for the inclusion of divergent thinking in its quadratic form for most outcomes (with the only exception being the realization of business field expansion plans). Additionally, following Wooldridge (2002), we use the likelihood-ratio test (LRT) to assess whether divergent thinking in its quadratic form contributes to the model.Footnote 15 The test shows that the quadratic term is significant for all outcomes, even though the p-value for realized plans of field expansion is only 0.095. Finally, we assess the fit of our specifications using the AIC, which confirms that the model including squared divergent thinking fits the data better for all outcomes apart from whether the entrepreneurs realized field expansion plans. Overall, we find evidence of a non-linear relation between divergent thinking and business survival, applications for patents or trademark protection, and having employees. We find slight evidence for potential non-linearities for the rest of the growth outcomes, as the inclusion of divergent thinking in its quadratic form is relevant for the model.Footnote 16

As we have hypothesized in Section 2.3.2 that the relationship between divergent thinking and entrepreneurial outcomes in the post-launch phase might be negative for very high levels of divergent thinking, we conduct an additional test in panel C of Table 2. Here, we split the divergent thinking factor into quartiles (baseline, lowest quartile) and look at the results for the upper three quartiles. The results underline the non-linearity in the effects on business survival. While we do not find a statistically significant effect for the fourth quartile (\(b=0.025\), \(p=0.688\)), the marginal effects for the second quartile (\(b=-0.125\), \(p<0.05\)) and third quartile (\(b=-0.185\), \(p<0.01\)) are negative, statistically significant, and economically relevant (as they relate to relative effects of \(-\)17.6% and \(-\)26.1% in comparison to people in the first quartile who have an average survival rate of 71%). The effects of divergent thinking on applications for patents or trademark protection are highest in the fourth quartile, and we see decreasing marginal returns for having or hiring employees.

Estimated marginal effects of divergent thinking in \(t_{19}\) on post-launch entrepreneurial outcomes in \(t_{40}\). Note: The figure shows marginal effects of the divergent thinking factor 19 months after business foundations on post-launch outcomes 40 months after business foundation at different values of the divergent thinking factor with 95% confidence intervals

Finally, we further contrast these findings by plotting the marginal effects of divergent thinking on our selected outcomes. Figure 2 confirms our findings for business survival, patents and trademark applications, and having employees. Figure 2 shows that the relation between divergent thinking and survival is non-linear. When looking at the bottom of the divergent thinking distribution, there seems to be a negative effect. This provides suggestive evidence concerning why the overall linear effect on survival in Table 2 is not significant. In the case of applying for patents or trademark protection, we observe that the relation with divergent thinking is quasi-linear and always positive. If we compare very low and very high values of divergent thinking, the effect on patents or trademark protection is significantly different. Finally, we find an inverse U-shape relation of divergent thinking with job creation outcomes and regional expansions and a weaker inverse U-shape for field expansion outcomes. However, given that their confidence intervals overlap, these findings are not conclusive.

Overall, we find evidence supporting hypothesis H2, namely that the relationship between divergent thinking and entrepreneurial outcomes in the post-launch phase is not necessarily linear. This is particularly true for business survival, where we find a pronounced non-linear effect of divergent thinking. For exploratory innovations, we find evidence of non-linearities as well. In this case, we observe increasing marginal returns, as the highest effect is found at the top end of the distribution. For having or hiring employees, the relation rather follows an inverse U-shape, indicating decreasing marginal returns. For some of the other outcomes, results are partly inconclusive—due to overlapping confidence intervals, which might be due to the small sample size—but suggestive of potential non-linearities.

4.4 Moderation analysis

4.4.1 An interactionist perspective: the role of experience

Divergent thinking and entrepreneurial performance are not related in a vacuum. As theorized and shown by empirical studies, different factors are at play and might provide specific contexts in which the relation operates, as well as serve as mediators of the divergent thinking effect (Amabile , 1988; Baer , 2012; Gielnik et al. , 2012; Amabile & Pratt , 2016; Lex & Gielnik , 2017; Warnick et al. , 2021). Domain-specific skills, knowledge, and expertise play a significant role in the creative process (Sternberg , 2005; Gemmell et al. , 2012; Amabile & Pratt , 2016), yet evidence is mixed regarding the role of experience in creativity. Some argue that it is a necessary condition to generate novel and useful ideas, while others show that experience affects the ability to generate such ideas, as it creates a mindset that relies on routines and reinforced associations (Schilling , 2005; Agnoli et al. , 2019). Experience in a specific domain might inhibit the generation of new ideas, as well as the ability of creative problem-solving (Schilling, 2005). Entrepreneurs might develop functional fixedness,Footnote 17 a mindset that prevents individuals from exploring or considering different ideas or solutions to problems. Entrepreneurs who have found a way of solving a certain problem are likely to use the same path when similar or even different problems arise and thus ignore different and potentially better ideas to approach problems. On the other hand, experience facilitates the recognition of viable ideas and can therefore produce novel combinations of resources that end up in creative achievements (Tiwana & McLean , 2005; Taylor & Greve , 2006). Experienced entrepreneurs might prevent process losses caused by communication problems, coordination, or conflict management, all of which can foster innovation (Taylor & Greve, 2006). Furthermore, given the relation of experience and knowledge in entrepreneurship (Rae & Carswell, 2000), knowledge plays a paradoxical role as it supplies the resources from which novel ideas are generated, although it carries a potential inhibiting effect on creativity (Ward, 2004).

Previous evidence suggests that prior entrepreneurial experience helps entrepreneurs to avoid taking inefficient paths, even though they might initially appear to be novel and original (Baron & Ensley, 2006). The recognition of viable opportunities involves pattern recognition, for which cognitive frameworks acquired through experience play a significant role: experienced entrepreneurs have a better picture of viable opportunities than novice ones, as they connect the dots differently (Baron & Ensley, 2006). This goes in line with Agnoli et al. (2019), who argue that domain-specific experience acts as a mediator of divergent thinking, as it helps entrepreneurs to develop sophisticated strategies to optimally use their ideational abilities to carry through creative goals. In other words, experienced entrepreneurs have a more refined strategic thinking that controls ideation and selects more suitable ideas for different scenarios. Furthermore, evidence shows that the interaction of divergent thinking with knowledge and information (and therefore a level of domain-specific experience) moderates the effect of divergent thinking on different entrepreneurial outcomes (Gielnik et al. , 2012, 2014; Xiao et al. , 2022).

However, little is known about the potential moderating effects of different types of domain-specific experience, such as experience from self-employment and regular employment. There is, however, some suggestive evidence. For instance, earlier evidence shows that previous self-employment experience has in itself a positive effect on performance (Jovanovic , 1982; Ucbasaran et al. , 2003; Bosma & Van Praag , 2004; Cassar , 2014; Rocha et al. , 2015) and is linked to learning processes in terms of networking and venture management (Cope, 2011), which in turn might exacerbate the functional fixedness mindset. Likewise, experience from former regular employment might have an influence in ideation—as described in Bhide (1994). Many entrepreneurs generate ideas for new ventures from former jobs, and there is suggestive evidence that entrepreneurs who obtained their business idea from previous jobs have higher growth rates (Dunkelberg et al. , 1987; Parker , 2018). Not only that, different working environments might affect creative behavior (Ensor et al. , 2001; Dul et al. , 2011), and previous employment variety (e.g., occupation, industry) might influence the quality of creative achievements (Astebro & Yong, 2016). In a post hoc moderation analysis, we examine whether different types of domain-specific experience have heterogeneous moderating effects.

4.4.2 Moderating effects of experience

We use the specification in Eq. 2 and differentiate between types of experience. Table 3 shows the interaction effects of experience from self-employment and from regular employment for the relation between divergent thinking and the outcomes of interest in terms of coefficients from logit estimations. Experience from regular employment has a positive significant moderating role for patents or trademark applications, regional expansions, and the realization of field expansions (logit coefficient, \(\beta =2.195\), \(p<0.01\); \(\beta =2.196\), \(p<0.01\); \(\beta =0.816\), \(p<0.05\)). In turn, experience from self-employment shows a negative interaction effect for survival, applying for patents or trademark protection, and the probability of hiring employees between \(t_{19}\) and \(t_{40}\) (\(\beta =-0.722\), \(p<0.05\); \(\beta =-1.768\), \(p<0.05\); \(\beta =-1.025\), \(p<0.05\)). We do not observe any interaction effects of regular or self-employment on the probability of having employees or business field expansions. Identifying these interaction effects is difficult with the small sample at hand, and we will discuss this in Section 5.2. Table 6 in the Appendix shows the marginal effects of these interactions as predictive margins of our outcomes. There are significant marginal effects on business survival of having domain-specific experience only from regular employment (column 3) compared to not having experience neither from regular nor from self-employment (column 1). For other outcomes, although the effects are not significantly different from each other, they are all relatively large and significantly different from zero.

Overall, divergent thinking interactions with different types of domain-specific experience have a significant effect on most outcomes of interest. In particular, having domain-specific experience from regular employment has a positive moderating effect on exploratory innovations and the realization of business field expansion plans, whereas domain-specific experience from self-employment shows negative moderating effects on business survival, exploratory innovation, and job creation. This suggests that entrepreneurs with domain-specific experience from self-employment might develop a functional fixedness mindset that prevents them from exploring novel ways of approaching problems or new ideas. On the contrary, entrepreneurs with domain-specific experience from regular employment seem to gain from such experience, as they report better performance in terms of innovation and growth.

4.5 Robustness analysis

We turn now to consider the robustness of our conclusions to a variety of important issues. The results are reported in Table 7.

Distributional assumptions—probit vs. logit In Section 4.2, we have explained why the logit regression—based on the AIC and the correct prediction rates—is our preferred choice. Nevertheless, given the differences in the cumulative distributions at the tails, and the nature of some of our binary outcomes with low positive responses, we want to test the robustness of our results with respect to this distributional assumption and replicate our main results from panel A in Table 2 using a probit regression. Panel A in Table 7 in the Appendix shows that the marginal effects of the divergent thinking factor on business field expansions, regional expansions, having hired employees between \(t_{20}\) and \(t_{40}\), and the realization of field expansion plans are almost identical for both models. There are some differences for applying for patents and trademark protection and the probability of having employees. However, these differences are relatively small, and hence, the results are robust with respect to the distributional assumption.

Continuous mean index In order to test the robustness of the results in relation to the construction of our divergent thinking factor index, panel B of Table 7 shows the estimates when using the continuous standardized divergent thinking mean index. The marginal effects of the divergent thinking mean index closely resemble those of the factor analysis, particularly for the probability of applying for patents or trademark protection, having employees, expanding into new business fields, having hired employees, and realizing business field expansions. The largest difference can be found for regional expansions, where an increase of one standard deviation in the divergent thinking mean index is associated with an increase of 4.2 p.p. in the probability of expanding into new regions, whereas it was 4.9 p.p. with the factor index. Finally, as with the factor index, there is no significant relation between divergent thinking and business survival. Overall, the marginal effects are qualitatively and quantitatively very similar.

Panel attrition weights In panel C of Table 7, we replicate the analysis from Table 2 without using panel attrition weights (see Section 3.1 for a discussion). Marginal effects change only slightly. Variables that were significant in the main estimation remain significant. One exception is the results for patents, which becomes slightly smaller and loses statistical significance, most likely due to the small sample size. Hence, the results are robust with respect to attrition weights.

5 Discussion and conclusion

5.1 Key findings and implications

The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of divergent thinking in the third phase of the entrepreneurial process, namely the post-launch phase. Drawing upon the cumulative process model of creativity in entrepreneurship (Lex & Gielnik, 2017), we hypothesize that divergent thinking has a lasting effect on post-launch entrepreneurial outcomes up until 40 months after start-up and that this relation is not always linear. Finally, given that domain-specific experience allows entrepreneurs to recognize viable business opportunities more efficiently (Baron & Ensley, 2006), and it shapes individuals’ ideational abilities (Agnoli et al., 2019), we investigate whether different types of domain-specific experience act as a moderator of the effect of divergent thinking on entrepreneurial performance.

In this paper, we provide current robust evidence of the role of divergent thinking on different entrepreneurial outcomes in the post-launch phase of the entrepreneurial process. As Lex and Gielnik (2017) point out, a longitudinal analysis is necessary in order to test the model. Therefore, we use a representative longitudinal sample of 457 German entrepreneurs from a two-wave survey. We are able to test our hypotheses on business survival, patents or trademark applications, extensive job creation, business field expansion, and regional expansions, as well as on having hired employees in the past 20 months of the post-launch phase and having realized business field expansion plans. Additionally, our rich data set allows us to account for a broad set of potential confounders as control variables.

We find supportive evidence for our first hypotheses, as divergent thinking has a positive effect on post-launch innovation and growth outcomes 40 months after business foundation. Thus, we confirm our theoretical framework based on Lex and Gielnik (2017), as well as previous evidence in line with these findings (Morris & Fargher , 1974; Ames & Runco , 2005; Baron & Tang , 2011). Additionally, we find strong evidence of non-linearities in the relation of divergent thinking with business survival, confirming our hypothesis. Low divergent thinking values have a negative effect on survival and are significantly different from the positive effects observed for values at the top of the distribution. Even though we cannot argue that divergent thinking measures innovativeness itself, this finding is in line with Hyytinen et al. (2015), who show that start-up innovativeness is not necessarily associated with the probability of business survival in the early stages of firm development. For patents or trademark applications, the relationship is also non-linear, but it is always positive, i.e., it shows increasing marginal returns, confirming the expected relation of divergent thinking with innovation (Sarooghi et al., 2015). For job creation outcomes, the relation follows an inverse U-shape, indicating decreasing marginal returns. This is in line with the idea that extremely high levels of divergent thinking might be counter-productive (Rosenbusch et al. , 2011; Acar & Runco , 2015). For expansion outcomes, the relations tend to have an inverse U-shape, but results are not conclusive.

As for the moderating role of different types of domain-specific experience, we find supporting evidence of our hypothesis, as we find that experience from regular and self-employment has significant moderating effects for divergent thinking on most post-launch outcomes. Experience from regular employment has a positive interaction effect on the probability of applying for patents or trademark protection, having hired employees between survey waves, and having realized field expansion plans. This is in line with Dunkelberg et al. (1987) and Parker (2018), who describe how entrepreneurs take ideas from former regular employment to apply them into their new ventures, which is reflected in higher growth rates, and Madsen et al. (2003), who show that experience in previous employment influences the building of networks that secure venture growth. In turn, having domain-specific experience from self-employment has a negative moderating effect on business survival, patent or trademark applications, and the probability of having hired employees. These results are in line with the functional fixedness theory. Experience from previous self-employment might limit the capacity for ideation, as entrepreneurs might stick to previous processes and ways of solving problems. This seems to affect their capacity for creative problem-solving, which is reflected in their lower probability of survival, innovation, and job creation.

5.2 Limitations and suggestions for future research

We acknowledge that the scope of our results has its own limitations, and some of them are closely related to the survey data that we use. First, due to budget constraints and the limited interview time, we have to rely on a shortened version of the RIBS to measure the divergent thinking levels in our sample. While we believe that we have covered the most relevant aspects of divergent thinking with the chosen items—which is also supported by the strong predictive power of our estimates—grasping the variability of the entire construct by Runco et al. (2001) would have been more ideal. Clearly, considering several measures of divergent thinking (e.g., the Alternative Uses Task, Kuhn and Holling, 2009b; Hass , 2015), their correlations and stability over time in future research would be very beneficial and help to draw more robust conclusions. Second, all of the outcomes in the survey have been operationalized as dichotomous variables. An operationalization of the outcomes of interest as continuous variables might help identifying more accurate effects and might allow exploring potential heterogeneities in more detail. Additionally, we use a proxy for explorative innovation—whether founders have filed at least one patent application or applied for trademark protection—which might not cover the full bandwidth of innovative behavior and actions in the post-launch phase. Hence, broadening the scope of outcome variables in future research would also be beneficial. Third, our small sample makes it hard to identify non-linearities and interaction effects with precision. Given the suggestive evidence that we present, we encourage further research on these topics, ideally in a longitudinal setting with temporal separation of measurement to tackle potential common method biases. Especially, the non-linearity in the relation between divergent thinking and survival (but also some of the innovation and growth outcomes) seems to be a very interesting avenue for future research, as it could shed light on what an optimal level of divergent thinking might be.

5.3 Contributions and practical implications