Abstract

To deepen theory on the interplay between entrepreneurship and context, recent scholarship calls for more understanding on how entrepreneurs and stakeholders collectively do “contexts.” In this study, we examine how a dynamic and flexible incubation context is constructed by joint efforts between entrepreneurs and incubator management. Findings from a 4-month ethnography point to four practices—onboarding, gathering, lunching, and feedbacking—through which entrepreneurs and incubator management maintain a productive balance between agency and structure on a daily basis. These findings have several theoretical implications for theory on incubation processes and the entrepreneurship-context nexus.

Plain English Summary

Incubation research overlooks the artful social practices required to sustain a fruitful incubation context. To maintain a balance between entrepreneurial autonomy and guided entrepreneurship programs, entrepreneurs and incubator management mutually engage in four practices: onboarding, gathering, lunching, and feedbacking. Onboarding fosters a shared understanding of norms, values, and practicalities of participation. Gathering facilitates collective decision-making. Lunching maintains a desirable level of trust. Feedbacking enables the co-creation of ideas and maintains reciprocity. Our findings deepen theory on the interplay between entrepreneurship and context and contribute to research and practice on incubation processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the past decade, a growing number of studies aim to contextualize entrepreneurship theory given that contexts both promote and constrain entrepreneurial activity (Welter et al., 2019; Wigren-Kristofersen et al., 2019; Zahra et al., 2014). The turn towards contextualization has generated numerous insights into the ways in which different social structures (e.g., family, market, region, incubation, political, etc.) shape entrepreneurship (see Wigren-Kristoferson et al., 2022). Nevertheless, there are growing concerns that researchers continue to view contextualization as “a one-way relationship with context and community as given” (McKeever et al., 2015, p. 50), or assume entrepreneurs operate in a stable state (Wigren-Kristofersen et al., 2019). Welter and Baker (2020, p. 1155) recently lament that “measurement, modeling, and scholarly restraint have moved forward quickly, but our theorization of context has not.” Accordingly, there are growing calls for going beyond existing perspectives to deepen theory on the interplay between entrepreneurship and context (Ben-Hafaïedh et al., 2023).

Similarly, research into the social activities of entrepreneurship support organizations (ESO), in particular incubators, has recently suggested that scholarship direct their focus onto the often mundane, overlooked, and sometimes hidden organizational activities that constitute and sustain ESO contexts (Ahmad, 2014; Caccamo, 2020). In this literature, scholars have concluded that it is necessary to understand how the social, spatial, and material elements of an ESO interact to meaningfully understand the ways in which people in these contexts “do” activities such as incubation (Bøllingtoft, 2012; Caccamo, 2020; Nicolopoulou et al., 2017). Interestingly, incubators are thought to only function effectively when there is a degree of de-coupling between formal rules and actual practices to overcome “architectural rigidities” and embrace the uncertainty and ambiguity inherent to new venture processes (Ahmad & Thornberry, 2018; Busch & Barkema, 2020). Accordingly, this literature promotes the idea that a cultivation of an adaptive context is necessary for incubators to prosper, which entails the co-creation by stakeholders (e.g., entrepreneurs and incubator staff and managers) to reshape these relatively standardized entrepreneurship contexts. Despite the apparent significance and importance of structural adaptability, however, there is only limited understanding of how stakeholders (e.g., entrepreneurs and incubator staff and managers) collaboratively constitute incubation as adaptive contexts over time. Therefore, we aim to answer the following research question: how is an adaptive incubation context constructed by entrepreneurs and incubator management?

Building on Chalmers and Shaw (2017), we adopt an entrepreneurship-as-practice framework that enables us to reconceptualize contexts as relationally instituted through social practices (Champenois et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2020, 2022). We deploy this framework to ethnographically investigate the social construction of a renowned European incubation context for social entrepreneurship, which we call “Greater Good” (GG). The findings of our ethnographic study point to four practices—onboarding, gathering, lunching, and feedbacking—through which entrepreneurs and incubator management construct an adaptive incubation context on a daily basis.

These findings have three main theoretical contributions for theory on incubation and the entrepreneurship-context nexus. First, we theorize that the extent to which an incubation context can be considered a form of adaptive context is linked to the capacity to strategically endow agency to stakeholders (e.g., entrepreneurs, management, and staff) to ensure ongoing alignment with their unfolding needs and expectations. This view of incubation further extends our understanding of the ways in which incubator stakeholders diverge from the standardization which characterizes the incubation context by detailing the specific social practices involved in subverting “architectural rigidities” (Busch & Barkema, 2020; Nair & Blomquist, 2018; Nicolopoulou et al., 2017). Second, we reinvigorate the theorization of entrepreneurship contexts more generally by arguing that they are products of unfolding social practices enacted by collectives of practitioners. This contributes to contextualization research by theorizing social practices as the medium and means through which entrepreneurship contexts are collectively constructed (Anderson & Ronteau, 2017; Gaddefors & Anderson, 2017). We argue that this insight helps to minimize some of the methodological issues associated with imposing a top-down notion of context in theory elaboration. Finally, we suggest that entrepreneurial embeddedness is a more complex affair than presented in existing literature (Harima, 2022; Jack & Anderson, 2002; Korsgaard et al., 2022; Wigren-Kristofersen et al., 2019). In particular, we posit that one may be influenced by or involved in multiple practices, each with their own agent-structure relationships. Hence, the extent to which an entrepreneur is embedded in a context may be the extent to which they draw on elements of social practices as a resource for developing ventures.

2 Theoretical motivations

In the following section, we analyze the ESO literature to determine how elements of context and practice have been theorized by scholars. We then narrow our focus to theories that conceptualize ESOs as dynamic entrepreneurial contexts before outlining a practice theory approach to context that we will use to ground our ethnographic analysis of a social purpose incubator.

2.1 Entrepreneurial support organizations

Entrepreneurial support organizations (ESOs) are now well-established contexts of entrepreneurship. They encompass a range of intervention mechanisms that include incubators, science parks, accelerators, maker spaces, and co-working spaces (Bergman & McMullen, 2021), and provide services such as venture hosting, mentoring, business education, and access to capital (Woolley & MacGregor, 2021). Association with a high-status ESO can serve as an important form of credentialization for young firms (Yu, 2020), helping them overcome many of the liabilities of newness associated with nascent venturing. While the various forms of ESOs share overlapping aims, there is some differentiation in how these aims are configured and operationalized, which may reflect the regional or industry context in which the ESO operates (e.g., Amezcua et al., 2020; Sansone et al., 2020).

Mirroring the growth of ESOs, a now substantial body of literature uses diverse theoretical and empirical lenses to examine various research questions. A foundational strand of research considers questions relating to what ESOs are (Grimaldi & Grandi, 2005), what functions they provide within an entrepreneurial ecosystem (van Rijnsoever, 2020), what activities they undertake (Baraldi & Ingemansson Havenvid, 2016; Hackett & Dilts, 2004), and what strategies they should adopt to support entrepreneurs (Tang et al., 2021). A second body of literature has sought to measure the impact of ESOs, both on individual entrepreneurial firms (Woolley & MacGregor, 2021) and on broader economic growth (Wang et al., 2020). Far from being an unqualified success, scholars working in this area find their efficacy to be mixed (Lukeš et al., 2019), with some observing that entrepreneurs participating in an incubator and/or accelerator program may experience lower chances of venture survival than those not supported by such programs (Schwartz, 2013). A third focus of ESO literature examines the role of networks (van Rijnsoever, 2020), social capital (Hughes et al., 2007), and entrepreneurial learning (Sullivan et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021), with researchers emphasizing the importance of interaction and trust in effective entrepreneurial incubation. And finally, a small but expanding group of scholars is attempting to move analysis from the generalized components or strategies of ESOs towards more sociological and activity focused explanations (e.g., Shankar & Clausen, 2020).

2.2 Sociological and activity-focused perspectives on entrepreneurial support organizations

Recent scholars have suggested that ESO research remains under-socialized in terms of relational, intangible factors (Theodorakopoulos et al., 2014), and has a narrow focus on the provision of “techno-material resources and network access” (Bergman & McMullen, 2021, p. 2). This glosses the “idiosyncrasies of incubation as a social mechanism” (Ahmad, 2014, p. 375) and leads to an incomplete understanding of ESOs more generally. Recent studies on the activities of ESOs have offered a corrective by refocusing attention onto the often mundane, overlooked, and sometimes hidden organizational activities that constitute and sustain ESO contexts. This lens has offered complementary and sometimes counterintuitive explanations for the relative success or failure of an ESO. For example, Caccamo (2020) finds an important role of boundary objects in successfully mediating practices in innovation spaces. This research also demonstrates that ESOs cannot be reduced merely to the sum of their parts (i.e., the physical space, networks, and business education). Instead, scholars demonstrate that it is necessary to understand the ways in which people “do” higher-level contexts, such as incubation, by paying attention to the relations between social, spatial, and material elements (Bøllingtoft, 2012; Caccamo, 2020; Nicolopoulou et al., 2017; Scillitoe & Chakrabarti, 2010).

Our specific interest in this article is business incubation as a dynamic entrepreneurship context. One of the core puzzles around the diffusion of incubation contexts has been the apparent ease with which they have been replicated around the world (despite remarkably different social, cultural, and economic contexts). While Ahmad and Thornberry (2018) identify the elements of structure that enable this replication (e.g., services and strategy, knowledge structure, networking and cooperation, and the incubator manager), they also find that incubators only function effectively because of a de-coupling between formal rules and actual practices. Similarly, Nair and Blomquist (2021) explain how incubator coaches overcome “architectural rigidities” to provide value for entrepreneurs, often tweaking procedures and embracing the uncertainty and ambiguity inherent to new venture processes. From a more strategic perspective, Friesl et al. (2019) describe how incubator leaders make structural changes to adapt to a changing external environment, and Busch and Barkema (2020) show that cultivation of a flexible and reactive context is necessary to meet the evolving needs of incubator clients in Kenya. Clearly, therefore, for incubators to prosper, it is necessary for them to grant some agency to stakeholders (e.g., entrepreneurs and incubator managers) to reshape the relatively standardized structures of incubation. Despite the apparent significance and importance of structural adaptability, however, there is only limited understanding of how stakeholders collaboratively constitute and reshape incubation as an adaptive context over time.

2.3 A practice-theory perspective of entrepreneurship contexts

The recent recognition that fruitful incubation contexts demand an interplay between structural flexibility and stakeholder agency mirrors conversations ongoing in broader context and entrepreneurship research. The “context turn” in entrepreneurship theory has afforded many significant new insights into the environmental factors that enable and constrain entrepreneurship (see Wigren-Kristoferson et al., 2022), thus moving further away from entrepreneur-centric theory (Ben-Hafaïedh et al., 2023; Zahra, 2007). Yet, recent research cautions against the tendency to treat contexts as static residual categories or “milieus” that have a mechanistic and uniform influence on entrepreneurial agency (Welter et al., 2017; Zahra et al., 2014). Ben-Hafaïedh et al. (2023), for example, call for researchers to go beyond either agent- or structure-centric views, towards accounts that theorize the complex interplay between entrepreneurship and contexts. In other words, while context points to the many social structures that enable or constrain entrepreneurial agency (Jack & Anderson, 2002), scholars must also recognize the agency of stakeholders to act independently towards reshaping contexts. For example, Welter and Baker (2020) perceive a shift in contextualization research by emphasizing the importance of “doing contexts,” which they describe as the making, unmaking, and remaking of sites for entrepreneurship.

In fact, a growing number of scholars have already begun to develop a more dynamic and relational conceptualization of entrepreneurship and contexts (Fletcher, 2011; Gaddefors & Anderson, 2017) by theorizing the interplay between collective agency and structure occurring within social practices (Chalmers & Shaw, 2017; Thompson et al., 2020). As Champenois et al. (2020) show in their extensive review, the entrepreneurship-as-practice research tradition advances a view of contexts as unfolding products of social practices, defined as ongoing interactions between entrepreneurs, stakeholders, and social structures. Drawing on social theorists such as Pierre Bourdieu (Hill, 2018; Tatli et al., 2014), Anthony Giddens (Chiasson & Saunders, 2005; Fletcher, 2006; Sarason et al., 2006), Theodore Schatzki (Keating et al., 2013; Lent, 2020), and many others, this scholarship has pointed to social practices as the “site” of dynamic relations between collective agents and social structures, thus the locale of contextual reproduction and change (Thompson et al., 2022). What is more, this literature has detailed important components of unfolding social practices central to contexts that were previously overlooked, such as material (Tuitjer, 2022), temporal (Katila et al., 2019), and spatial (Cnossen & Bencherki, 2019) considerations. Despite these insights, however, most research in this stream remains conceptual, with relatively few scholars observing and examining social practices to further our understanding of the interplay between entrepreneurship and context.

Given the recent recognition in ESO literature that fruitful incubation contexts are those that facilitate structural adaptability, and context-based researchers recognizing social practices as the sites of contextual reproduction, in this study we ask: how is an adaptive incubation context constructed by entrepreneurs and incubator management through social practices?

3 Methodology and methods

To answer this research question, we conducted an ethnographic field study (Watson, 2011). Ethnography enables us to develop insights into social practices as the dynamic sites of relationships between the actions and utterances of people and the social structures within which those actions and utterances occur (Van Burg et al., 2020). It does so by prioritizing “hanging out with, joining in with, talking to and watching, and getting together the people concerned” (Schatzki, 2001, p. 5). In other words, ethnography enables entrepreneurship researchers to produce an accessible, contextualized, and “grounded” account of “how things work” in everyday practitioner reality, thus convincingly claim that findings are rooted in observations.

3.1 Research site

We study the social construction of an incubation context for social entrepreneurship, which we call “Greater Good”. GG provides an interesting setting to study how a dynamic incubation context is constructed through social practices, because it showcases a context in which incubation can be a prosocial mechanism. Specifically, the incubator is built on a shared belief that creating positive social and environmental impact does not happen in isolation but requires collaborative action. Furthermore, GG provides an insightful case due to its long tenure. The incubator started 10 years ago as a naturally formed community consisting of a small number of social entrepreneurs and has since then grown to a renowned organization in Europe that has supported over a thousand social enterprises in starting and growing their businesses. The growth of incubator membership has necessitated more direct involvement by management, while at the same time, GG relies on the community of social entrepreneurs to facilitate and adapt the incubation process.

3.2 Data collection

This study began in 2019 when the first author was granted full access to conduct an ethnographic study. Our prior relationship with GG directors helped us secure long-term access and collect observational data at all GG community spaces and events. In line with ethnography, we gather data using participant observation, audio recordings of real-time activity, and interviews with key informants, which we elaborate on below (see Table 1). All names are anonymized. The incubator management, henceforth management, is made up of “hospitality hosts,” “program managers,” and “community catalysts.”

3.2.1 Participant observation

The first author, Amba, conducted fieldwork as a participant-observer for 2 days a week, on average, over the course of 4 months. The initial research question that guided the observations was “how does GG build and maintain a community of entrepreneurs in and through practices?” Amba began by paying close attention to routine practices that were identified as “community events” on the “event board” of the incubator. Amba took a practitioner perspective by informally talking to entrepreneurs and management and shadowing them in regularly scheduled practices and events, such as new member introduction sessions (“onboarding” sessions), community drinks, daily community lunches, community football, formal and informal feedback sessions, and community gatherings. When invited, Amba also provided assistance in hosting sessions and events. By participating in these sessions, she was able to gain first-hand experience into the practices of GG. Participant observations were supported by writing observational field notes and memos. In total, she collected 50 pages of field notes that were descriptive in nature and entailed details of site-specific practices, including language, bodily movements, and materials used in interactions.

3.2.2 Audio recordings

To supplement participant-observations, Amba also gathered even more detailed data on certain routine practices by collecting audio recordings of naturally occurring conversations. Audio recording real-time utterances and activities is valuable for studying practices (Thompson et al., 2020) as it allows researchers to have a denser record of practices than available through memory, retrospective interviews, or surveys. The collective performances of practices are often rapidly executed in talk and action, which makes it difficult for the researcher to note them down in detail in the moment. After getting informed consent of the participants to record the session, Amba set up a microphone in the room and started recording all communications until the end of the session.

3.2.3 Interviews

Although not prioritized in this study, Amba also conducted seven semi-structured interviews, as well as many informal conversations, with management and entrepreneurs to gain some background information regarding the history of the incubator, why they engage in certain practices identified during participant-observation, and how they experience the effectiveness of these practices. GG practitioners use the term “community,” and so we adopted this term in interviews and asked what their community entails, which actors are involved in community building, which practices they use to build the community, why they perform certain practices, and how these practices have evolved over the years. While these interviews and conversations provided substantial insights, direct observation was prioritized in our data analysis due to its strength in countering retrospective bias and in getting to know the practices from within. Table 1 provides an overview of data collected.

3.3 Data analysis

Our data analysis took place in two phases. The first phase aimed to understand which practices of entrepreneurs and incubator management were constitutive of the incubation context. The aim of the second phase was to deepen analyses of the results of phase one, paying close attention into how the practices were composed and how they enabled the practitioners to collectively construct the incubation context. In doing so, we prioritized “thick description” of everyday empirical observations over the generation of new mechanisms and constructs (Nicolini, 2017).

3.3.1 Identifying practices

Following ethnographic methods, we adopted no set analytical categories prior to entry into the field, although this exploratory research used a practice theory approach as a sensitizing frame. Our analysis started during data collection by noting moments of surprise or insights, which enabled some initial thoughts about routine patterns of action indicative of key practices. After a period of time in the field, we would meet and read through and reflect on the field notes developed during the shadowing, writing down key ideas and insights from the meeting. In doing so, we were able to eliminate certain routine practices, such as inspirational talks, that were present at the field site, but were not central to the social construction of the incubation context. Overall, this resulted in identification of four routine practices: onboarding, gathering, lunching, and feedbacking that we, as well as practitioners, find particularly relevant for constructing and maintaining an incubation context.

3.3.2 Analysis of practices

In the next step, we deepened our analysis of the practices we identified. We followed Schatzki (2012) and defined a practice as an open-ended, spatially-temporally dispersed nexus of doings and sayings. Doings and sayings are organized by their sequence, practical understandings, and teleology. Moreover, material arrangements also structure practices by channeling, prefiguring, and facilitating them. In line with the principle of abductive live coding (Locke et al., 2015), we used this definition as a coding framework to systematically interrogate the dimensions that compose each practice (see Table 2).

This process involved focusing on each practice in turn and coding the relevant data based on the categories of sequence, practical understandings, teleology, and material arrangements. This enabled us to compare different instances of a given practice, to understand the commonalities of their performance and the possible implications for the construction of the incubation. Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6 provide an overview of this process.

4 Findings

In this section, we present a detailed analysis of the four main practices constitutive of GG as an adaptive incubation context: onboarding, gathering, lunching, and feedbacking. Table 7 provides details of the four practices and their structure and agency properties. Below, we present a “thick description” of each practice in which we detail the intricate relations between agency and structures, and their relationship with constructing an adaptive incubation context.

4.1 Onboarding Practice

The first practice through which GG’s management and entrepreneurs socially construct an adaptive incubation context is called “onboarding.” As indicated by a community catalyst of GG, the challenge is that: “Ten years ago when GG was founded, we agreed on certain cultural rules and values, but when that community grows, it is super difficult to guarantee that.” As we show below, onboarding practice provides structures to foster a shared understanding of the norms, values, and practicalities of the incubation context in order to enable new cohorts of entrepreneurs to effectively participate in the incubation process.

In terms of routine, onboarding is conducted weekly for any new members—on average three or four—and is led by a community catalyst. The sequence of the onboarding practice always starts with the community catalyst showing new members to a round circle of seats and sharing the “origin story” of the incubator. In one instance, a community catalyst, Rosa, explained to the new members why she believes it is important to share this story, stating, “that it is where the DNA [of the incubator] originates…and we are still working with [that same DNA] today and we are truly trying to maintain it.” Beginning the practice with the incubator’s “origin story” invites new members to become part of the “story,” setting both a sociohistorical consciousness of the incubators’ past while also aiming to instill future behavioral expectations of participation. Next, a community catalyst engages with new members to learn their stories. Demonstrating this interest in members is important, not only on an interpersonal-level, but to also inform new members that “one person is part of the bigger picture, because that's the whole point of being together” (Norah, co-founder). To facilitate this, the community catalyst asks members to write down what they need from the community, their expertise or what they can give to the community, and their passion on Post-it Notes. The new members take a couple of minutes to write down their “gives, gets, and passions,” after which they share it with each other. The use of Post-it Notes, in terms of materiality, enables the community catalyst to later on remember each new member to connect them to others based on interests or expertise.

The community catalyst then moves on to explain the material resources and tools available to entrepreneurs, including the website, the community app, and the calendar by showing them on her laptop. These material arrangements ensures that “all members have a connection to each other no matter what: There is a community app that is available to everyone and then through that they're connected to each other. So, there’s a minimal level of infrastructure that we created for that connection.” Throughout the onboarding practice, the community catalyst stresses that there is much GG can offer to new members, including interesting events and valuable connections, but that they need members’ active participation in making connections and reaching out for help as well.

The onboarding practice continues with a spatial tour of GG, starting at the community room, which includes a shared kitchen area (see Fig. 1). In the kitchen area, the community catalyst not only positions her body and movement to show how the different kitchen tools can and should be used, but also stresses “you can have the mindset that everything here in the space is our space so also your space. …really feel that ownership.” Apart from having the symbolic function of doing things collectively instead of individually, it also serves the practical function of building connections: “You just have different kinds of chat at the dishwasher or coffee machine. … How often do I see people having a chat at the coffee machine or people introducing each other, I see that a lot.”

The tour moves on to include an overview of the material arrangements of the event board (see Fig. 2) and calendar board (see Fig. 3). The community catalyst explains that this is another opportunity to connect with outside stakeholders, stating, “If there are names on here, or a company name that you think, ‘Hey, I really want to connect with these people’, we can always connect you with them.” In doing so, the community catalyst draws attention to the importance of the event and calendar boards as material objects that visibly and instrumentally signify the normative importance of participating in community events as well as facilitate information-sharing regarding future opportunities for networking.

The onboarding practice closes at the coworking space with a request to take a headshot of new members to add their photos to the member wall (see Fig. 4). The member wall is, as explained by the community catalyst, “a photo with cards underneath it with your name, your company name, and the SDG you're working on,” which helps entrepreneurs identify others with similar interests. In short, the onboarding practice enables a normative understanding and opportunities for participation, a key part in ensuring GG is an adaptive incubation context.

4.2 Gathering practice

The second practice through which GG’s management and entrepreneurs socially construct an adaptive incubation context is called “gathering.” GG management and entrepreneurs are keenly aware that engaging with a community of more than 400 entrepreneurs requires a flexible and participatory architecture that promotes co-creation and accounts for the uncertainty of entrepreneurs’ evolving needs. GG management sees the risk of over-structuring the context, as explained by one of the community catalysts: “So actually I think one of the biggest mistakes people make in creating, maintaining, hosting and growing community is over engineering, actually doing too much. I mean it's like planting a garden. How do you do that? Well, you make sure that the conditions are right. … If every single day you're watering, or experimenting, or doing different things and constantly tampering with the garden you're getting in the way of a living system that actually has a lot of its own intelligence and wisdom.” GG routinely organizes a large community gathering event twice a year for all of its members, using some smaller “gatherings” to determine which topics will be the focus in each large event. This ensures that the context remains receptive and adaptive to entrepreneurs’ needs. We detail the gathering practice below.

Community catalysts and entrepreneurs carry out the smaller gatherings in a joint effort. After invitations are distributed among entrepreneurs and acceptances are received, the smaller gathering is scheduled and takes place in a breakout room separate from the community area. In terms of material arrangements, participants sit around a round table with pens, Post-it Notes, drinks, and cake. These objects are not only practical tools for capturing ideas and feedback but also symbolic of an informal atmosphere. One of the community catalysts stands in front of a flipchart and begins by expressing gratitude for the entrepreneurs’ involvement and stresses the importance of their active participation in the planning stages of the large community gathering. Before reviewing the agenda of the meeting, everyone introduces themselves. Introduction rounds are part of the sequence of most practices in GG, since it provides a practical opportunity for entrepreneurs to get to know each other and potentially find valuable connections.

After the introduction round, community catalysts move on to communicate the purpose of the gathering. Janita, one community catalyst, described it during the large community gathering in the following way: “In the community gathering there is a mutual relationship. One side of the coin is how do you want GG to support you in reaching your goals? And the other side of the coin is what are you willing to do to shape this community?” However, during the gathering practices, the performance of the practice is sometimes contested. For example, after the explanation by the community catalyst, an entrepreneur asks: “What is the goal? So, after the community gathering, the things we are discussing with each other on that hour, you as management want to do something with that and make changes?” The community catalyst replies: “Not we as GG, but we as a community.” One of the community catalysts explains why they consider it so important to organize activities bottom-up and to ensure the involvement of the entrepreneurs: “Because when members are willing to actually do the work themselves and co-create, you know you have traction. Instead, when you put on an event, you go to the meeting about it and you as a catalyst walk away with loads of work to do, that should be the sign that the event isn't wanted or needed.”

After the purpose of the large community gathering is made clear, community catalysts show a list of some suggested topics, created by the catalysts on a flip chart, to help get entrepreneurs thinking of their own possibilities. Then, entrepreneurs pair up to freely brainstorm about topics, which they write down on Post-it Notes. After everyone has voiced their ideas, some topics are merged and votes are counted to determine the four topics with the most votes that will be discussed during the large community gathering with all community members.

Overall, facilitating this type of collective decision-making allows for receiving and integrating feedback from multiple entrepreneurs. One discussion, for example, led to the insight that much of what the entrepreneurs expressed they needed was already being available at GG, but was just not visible enough. Increasing the visibility of GG’s offerings was consequently picked up at the large community gathering, during which time groups were formed around creating a “check in—check out” member wall. On this wall, members can communicate what kind of expertise they can offer, what they need for that day, and if they do not want to be disturbed. The results of these routine small and large gatherings highlight an important explanation for why gathering practice is such an important practice to practitioners—it constructs a flexible and participatory architecture in which decisions and actions are made collectively, which ultimately enables GG to better adapt their services to the needs of their members.

4.3 Lunching practice

The third practice through which GG’s management and entrepreneurs socially construct an adaptive incubation context is called “lunching.” A major challenge that both management and entrepreneurs recognize is developing and maintaining a desirable level of trust among entrepreneurs (and management). This is especially true as GG has grown to such a large size. For example, one of the older members expresses that because of the growth of GG, it feels less like a community: “Community means like everyone knows each other and hangs out with each other at a minimum. That’s like the minimum requirement for a community. Otherwise, we're a bunch of people sitting together. … It now has become much bigger. When it becomes bigger you lose some of that intimacy, right?” To build trust, entrepreneurs and management conduct multiple practices to create opportunities for spontaneous socializing, such as playing football, having community drinks, and a daily community lunch. Especially lunching practice is viewed by management and entrepreneurs alike as a major positive force in creating and maintaining trust. Among entrepreneurs, it is the most frequently named occasion when asked how they have gotten to know one another. Hence, lunching practice is a key component of an adaptive incubation context. We detail the lunching practice below.

Each occasion of the lunching practice begins in the morning, when entrepreneurs can sign up for lunch by writing their name on a small chalkboard located in the community area. The presence of the chalkboard, a material object in a shared area, reiterates and reminds entrepreneurs of a participation opportunity by making visible who will join the practice public. At 12:30 p.m., the host rings a bell to notify entrepreneurs that it is time for lunch. The community catalyst explains that this is an important part of the practice, as previously, when they offered a buffet style lunch “people just came when they wanted. So, you saw if no effort was made from our side to facilitate to sit at the table with each other, that people did not feel that responsibility to do that themselves.” Hence, maintaining a lunching practice that supports the teleology of fostering trust within the community requires the joint effort of both management and entrepreneurs.

Furthermore, with no assigned seating, lunching practice enables entrepreneurs to freely choose where to sit, providing them the opportunity to get to know other people (see Fig. 5). Materially arranging the lunching practice in such a way encourages serendipity, as noticed by Chris (entrepreneur), “You can just end up sitting next to someone who can help you further.” Our analysis of the many observed instances of lunching practice finds that when entrepreneurs who have not met before sit next to each other, the most commonly asked question is, “What do you do?” This fuels a conversation about the projects they are working on, the societal issues they are trying to solve, and sometimes also the struggles they face. Oftentimes, though, conversations during the lunching practice are more informal, including topics such as children, food, holidays, politics, and so on.

Due to it being a daily ritualized practice, lunching practice creates an atmosphere in which entrepreneurs are invited to interact with each other in an informal way. On the one hand, the practice is enacted by management as a way to structure the entrepreneurs’ behavior by setting the location, time, and open seating arrangement for interaction possibilities. On the other hand, entrepreneurs’ participation in the spontaneous interactions works to reproduce the everyday practice. An important explanation of why lunching is an important practice is because it creates a setting where there is opportunity for serendipitous conviviality, which plays an integral role in building trust that enables an adaptive context.

4.4 Feedbacking practice

The fourth practice through which GG’s management and entrepreneurs socially construct an adaptive incubation context is called “feedbacking.” The social construction of this incubation context not only rests on making social connections and establishing membership as an end in itself, but also is oriented toward entrepreneur’s instrumental need of acquiring new knowledge related to their venture. A key challenge is that entrepreneurs have these instrumental needs, but limited resources to fulfil them. And yet, while each entrepreneur has their own individual needs, we observed it is also common for entrepreneurs to participate in open sessions, which we call feedbacking practice, to co-develop ideas and think of solutions to problems in a collaborative manner. The egalitarian and collective nature of this learning fulfils not only the instrumental need of one entrepreneur, but also deepens the relationships among entrepreneurs. Furthermore, because the practice is recurrent, entrepreneurs take turns being the focal point of the feedback and then reciprocity results from the continued enactment of the feedbacking practice itself. Hence, feedbacking practice enables participants to acquire new knowledge and reciprocate, ensuring that the context remains adaptive.

Occasions to engage in the feedbacking practice occur once every month. The first step in the sequence of the practice is that a community catalyst typically opens the practice by welcoming the entrepreneurs and introducing the entrepreneur who is looking to receive feedback. Subsequently, a community catalyst will describe the agenda of the practice, including asking participants to use Post-it Notes to write down feedback and contact details. In one session, the community catalyst directs attention to the material arrangement of the practice by sharing that the Post-it Notes are important “so she [Joyce, entrepreneur] also has a way to reflect on the feedback that she heard at the session. … if you want to give your contact for a chat later, feel free to do that.” The use of Post-it Notes facilitates the building of connections and accommodates a flow of knowledge sharing in the session, allowing as many entrepreneurs as possible to have the opportunity to share their experiences or provide their feedback.

The focal entrepreneur receiving the feedback typically explains what their business entails and how it aims to address a specific social issue. Usually, when the concern raised by the entrepreneur is clear, a conversation in which multiple pieces of advice are being shared naturally follows. Community catalysts meanwhile guide the conversation by making sure that it continues to focus on answering the question raised by the focal entrepreneur, that all present entrepreneurs have an equal voice so that participation is not dominated by any particular person and sometimes summarizing important parts of the conversation on a flip chart. The flip chart consequently plays a useful role in keeping a visual account of the key feedback that could be useful for the focal entrepreneur.

This is not to say that feedbacking practice is enacted without disagreement. For example, during one instance in which the focal entrepreneur Menno asked for advise on finding a co-founder, one entrepreneur in the feedback session gave the feedback that Menno can better quit with his social venture, because he has not generated revenue yet. According to the entrepreneur providing the feedback “this is a sign of the market that there is no real need.” Other entrepreneurs in the session tried to be more constructive by providing other perspectives on how to solve the issue with generating revenue. When the entrepreneur continued to provide arguments why it would be better to quit, also the community catalyst intervened by stating: “I also suggest to respect Menno’s question, because he would like to receive feedback on the question about a co-founder.” After that, the conversation continued in which multiple types of advice are shared about how to attract the right people to make the business a success. Typically, after the community catalyst has officially closed the session, some participants still hang around to chit-chat, continue the conversation, or exchange contact information. Overall, the feedbacking practice enables entrepreneurs and management to co-create ideas that has also the effect of ensuring the context remains adaptive to emergent needs.

5 Discussion

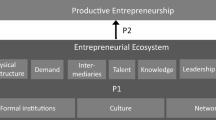

Our study reveals that GG is both a highly ordered as well as carefully orchestrated adaptive context for supporting nascent entrepreneurial firms. Surprisingly, past research has prioritized analyses of standardized rules or principles of incubation, yet only minimally examined the actual social practices which sustain these adaptive contexts (see Bergman & McMullen, 2021). Whereas, techno-material perspectives on incubation—a focus on constituent parts—have prevailed in existing studies, in this study, we show through an in-depth ethnographic analysis how an incubation context is adaptively (re)constructed through the efforts of incubator management and entrepreneurs, each of whom strategically asserts their agency through practices that constitute the context for action (see Fig. 6). In particular, we find these practices create a shared understanding of the normss, values, and practicalities of participation in the incubation process; allow incubator management to remain flexible to emergent needs; develop and maintain a desirable level of trust among entrepreneurs; and foster reciprocity among entrepreneurs. Furthermore, our findings offer a new insight into the fluctuating salience of structure and agency through different incubation practices. These findings demonstrate the ways in which management and entrepreneurs work collaboratively to maintain a degree of structural adaptivity in the context of business incubation. In the following section, we will explore the theoretical implications of our research.

5.1 Theoretical implications

While a focus on social practices may bring to mind unimportant everyday activity, we demonstrate that social practices serve a range of purposes and have implications far beyond their surface meaning (e.g., eating lunch). Rather, it is through the layering and temporal enactment of these practices that they facilitate the co-creation of an adaptive context. Our findings show that the sequencing of practices plays a crucial role in socializing newcomers into an adaptive incubation context, while also giving them some scope for agency to reshape elements of the context. Specifically, we find that structure salience was higher during the initial practices (onboarding) as management attempted to imprint core norms and values onto entrepreneurs. This was followed by practices that afforded more salience to entrepreneurs’ agency (gathering), and by practices that were more finely balanced (lunching, feedbacking). This suggests that entrepreneurs are successfully embedded in the incubator when they begin to draw on elements of context as a resource (e.g., asking for advice, accessing networks, using technologies).

We propose that this purposeful varying of structure-agency salience serves the function of preventing incubation from being perceived as too brittle (i.e., overly top-down or prescriptive), which would alienate the high-status, creative, and heterogenous cohort of entrepreneurs that are typical of our case study incubator. Unlike other institutionalized contexts, where there is some form of coercion or sanction for people to behave or act a certain way (e.g., a prison environment (Giallombardo, 1966) or a legal setting (Siebert et al., 2017), social purpose incubators require purposive and ongoing buy-in from entrepreneurs, and this in turn requires greater adaptivity from incubator management as they orchestrate elements of the context through social practices.

These findings, therefore, extend prior research that examines the inner workings of ESOs in a number of ways. While past research has considered how external factors such as market disruption can spur changes to an incubation context (Friesl et al., 2019), our findings show how these changes can occur endogenously through changes in enacting social practices. This is a departure from mainstream understanding of incubation, which has emphasized the “significant structural robustness” of incubation contexts (for example, see Ahmad & Thornberry, 2018, p. 1191). While prior research has shown the significance of individual incubator management going “off script” when delivering incubator services (Nair & Blomquist, 2021), our systematic and longitudinal analysis of incubation reveals a set of more strategic and routinized practices that are enacted to provide adaptability. Thus, we theorize that the extent to which an incubation context can be considered a form of adaptive context is linked to the capacity to strategically endow agency to stakeholders (e.g., entrepreneurs, management, and staff) to ensure ongoing alignment with their unfolding needs and expectations. This view of incubation further extends our understanding of the ways in which incubator stakeholders diverge from the standardization which characterizes the incubation context by showing the specific practices involved in subverting “architectural rigidities” (Busch & Barkema, 2020; Nair & Blomquist, 2018; Nicolopoulou et al., 2017).

Furthermore, our study contributes to a broader conversation on the interplay of context and entrepreneurship. Specifically, we use social practices as a window to view the influence of both structural and agentic factors on the overall functioning of an ESO context. This framing reinvigorates the theorization of adaptive contexts by conceptually equating them to unfolding social practices enacted by collectives of practitioners. In other words, we propose that social practices are the medium and means through which entrepreneurship contexts are collectively constructed (Anderson & Ronteau, 2017; Gaddefors & Anderson, 2017), and thus minimize some of methodological issues associated with imposing a top-down notion of “context” in theory elaboration. While a focus on social practices in entrepreneurship studies is already underway, Champenois et al. (2020) recently found in their review that existing studies have primarily been concerned with either conceptually demarcating the difference from traditional ontologies, epistemologies, and methodologies. As a result, there are still few studies that empirically deploy a social practice perspective to examine the collective “doing” of entrepreneurship contexts. We contribute to this literature by showing how an analytical consideration of social practices provides researchers a more concrete unit of analysis for unpacking the dynamic and socially constructed nature of entrepreneurship contexts. Accordingly, future research now has the means to embrace the explanatory power of “everydayness” (Welter et al., 2017) by theorizing the ways in which quotidian social practices are the medium and means through which entrepreneurs and stakeholders “do context.”

Finally, while existing contextualization research has long acknowledged that entrepreneurs are embedded within social structures (Jack & Anderson, 2002), our study further refines this view by suggesting entrepreneurial agency is dependent on particular agent-structure relations constitutive of a given social practice. Whether this is by design or chance, certain practices enable agents more space for improvisation and freedom in their structural components, while others constrain their agency. For example, lunching practice in this study provides entrepreneurs with a loose structure of interaction that enables them to improvise and interact freely. On the other hand, onboarding practice is a highly structured practice in which entrepreneurs have less agency to deviate and adapt the practice to their will. In relation to a given practice, entrepreneurs may have more opportunity for agency when structures are ambiguous and flexible, such as when shared practical knowledge, rules, and teleologies are incomplete or ambiguous. However, a lack of or ambiguity of structure also increases collective action costs, hindering productive interaction by agents. It follows that if entrepreneurship contexts are constituted by a multiplicity of social practices, then spaces for entrepreneurial agency are related to a multiplicity of webs of agent-structure relations. Accordingly, embeddedness is a complex affair in which one may be influenced by or involved in multiple practices constitutive of social networks, institutions, places, families, communities, social classes, or other contexts (Harima, 2022; Korsgaard et al., 2022; Wigren-Kristofersen et al., 2019), each with their own unfolding agent-structure relationships.

5.2 Future research directions

Our study has several limitations, which also provide several opportunities for future research. First, we are aware that ethnography enables us to produce findings limited to the observed practices at our field site, with all its idiosyncrasies and relational influences. Nevertheless, our objective is not to produce generalizable practices that transcend space and time (if that is even possible), but rather to provide a fine-grained analysis and theoretical explanations of some of the ways in which practitioners construct an adaptive incubation context. That said, it is important that future studies build a larger body of research focused on the variety of practices, their origins, transmission, and transformation, in different settings. Doing so will help develop an understanding of the similarities and differences between settings, including analyses of practices that fail to ensure an adaptive context. Future research, for example, may examine incubation contexts of different scales and with different frequencies of practices being performed. Also, it would be valuable to examine settings with more or other types of material limits for the performance of social practices, for example, during a lock-down during which it is not be possible to make use of a physical space. Finally, this study relies heavily on the researcher-as-instrument (ethnography) research tool. Using video ethnographic data could be a way to further our understanding of practices in incubation contexts, as it allows analysts to extent their view through multiple cameras, develop deeper insights into the fast-paced world of practices (Ormiston & Thompson, 2021).

5.3 Practitioner implications

Our findings also have implications for practitioners involved with incubators and other ESOs. Importantly, our research suggests following a recipe approach to incubation potentially misses the artful social practices required to sustain an incubation context. Trying to copy incubation contexts can be problematic, which is indicated by Samra-Fredericks (2003) as well who states that effective performance is relational and situation bound and thus practices cannot be planned, but need to be developed in context and in interaction with the people and the material world that are part of that context. Furthermore, the insight that the practices described in this study have a very sophisticated structure-agency balance may provide inspiration for incubator management and entrepreneurs to reconceive, for all practical purposes, their current and desired balance in structure and agency. For instance, we caution incubator management against the strict adoption and adherence to practices developed elsewhere (e.g., Silicon Valley). Our research suggests that a more fruitful approach will be to allow for entrepreneurs and incubator management to experiment with practices and their dimensions to collectively construct an adaptive context, which accommodates local entrepreneurs’ needs and desires.

References

Ahmad, A. J. (2014). A mechanisms-driven theory of business incubation. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 20(4), 375–405. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-11-2012-0133

Ahmad, A. J., & Thornberry, C. (2018). On the structure of business incubators: De-coupling issues and the mis-alignment of managerial incentives. Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(5), 1190–1212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9551-y

Amezcua, A., Ratinho, T., Plummer, L. A., & Jayamohan, P. (2020). Organizational sponsorship and the economics of place: How regional urbanization and localization shape incubator outcomes. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(4), 105967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.105967

Anderson, A. R., & Ronteau, S. (2017). Towards an entrepreneurial theory of practice; emerging ideas for emerging economies. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 9(2), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-12-2016-0054

Baraldi, E., & IngemanssonHavenvid, M. (2016). Identifying new dimensions of business incubation: A multi-level analysis of Karolinska Institute’s incubation system. Technovation, 50–51, 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2015.08.003

Ben-Hafaïedh, C., Xheneti, M., Stenholm, P., Blackburn, R., Welter, F., & Urbano, D. (2023). The interplay of context and entrepreneurship: The new frontier for contextualization research. Small Business Economics.

Bergman, B. J., & McMullen, J. S. (2021). Helping entrepreneurs help themselves: A review and relational research agenda on entrepreneurial support organizations. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587211028736

Caccamo, M. (2020). Leveraging innovation spaces to foster collaborative innovation. Creativity and Innovation Management,2018, 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12357

Bøllingtoft, A. (2012). The bottom-up business incubator: Leverage to networking and cooperation practices in a self-generated, entrepreneurial-enabled environment. Technovation, 32(5), 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2011.11.005

Busch, C., & Barkema, H. (2020). Planned luck: How incubators can facilitate serendipity for nascent entrepreneurs through fostering network embeddedness. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258720915798

Chalmers, D. M., & Shaw, E. (2017). The endogenous construction of entrepreneurial contexts: A practice-based perspective. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 35(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615589768

Champenois, C., Lefebvre, V., & Ronteau, S. (2020). Entrepreneurship as practice: Systematic literature review of a nascent field. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 32(3–4), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2019.1641975

Chiasson, M., & Saunders, C. (2005). Reconciling diverse approaches to opportunity research using the structuration theory. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(6), 747–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.07.004

Cnossen, B., & Bencherki, N. (2019). The role of space in the emergence and endurance of organizing: How independent workers and material assemblages constitute organizations. Human Relations, 72(6), 1057–1080. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718794265

Fletcher, D. E. (2006). Entrepreneurial processes and the social construction of opportunity. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 18(5), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620600861105

Fletcher, D. E. (2011). A curiosity for contexts: Entrepreneurship, enactive research and autoethnography. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23(1–2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2011.540414

Friesl, M., Ford, C. J., & Mason, K. (2019). Managing technological uncertainty in science incubation: A prospective sensemaking perspective. R and D Management, 49(4), 668–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12356

Gaddefors, J., & Anderson, A. R. (2017). Entrepreneursheep and context: When entrepreneurship is greater than entrepreneurs. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(2), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-01-2016-0040

Giallombardo, R. (1966). Social roles in a prison for women. Social Problems, 13(3), 268–288. https://doi.org/10.2307/799254

Grimaldi, R., & Grandi, A. (2005). Business incubators and new venture creation: An assessment of incubating models. Technovation, 25(2), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(03)00076-2

Hackett, S. M., & Dilts, D. M. (2004). A systematic review of business incubation research. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(1), 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:jott.0000011181.11952.0f

Harima, A. (2022). Theorizing disembedding and re-embedding: Resource mobilization in refugee entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 34(3–4), 269–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2022.2047799

Hill, I. (2018). How did you get up and running? Taking a Bourdieuan perspective towards a framework for negotiating strategic fit. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 30(5–6), 662–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2018.1449015

Hughes, M., Ireland, R. D., & Morgan, R. E. (2007). Stimulating dynamic value: Social capital and business incubation as a pathway to competitive success. Long Range Planning. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2007.03.008

Jack, S. L., & Anderson, A. R. (2002). The effects of embeddedness on the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(5), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00076-3

Katila, S., Kuismin, A., & Valtonen, A. (2019). Becoming upbeat: Learning the affecto-rhythmic order of organizational practices. Human Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719867753

Keating, A., Geiger, S., & Mcloughlin, D. (2013). Riding the practice waves: Social resourcing practices during new venture development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(5), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12038

Korsgaard, S., Wigren-Kristoferson, C., Brundin, E., Hellerstedt, K., Alsos, G. A., & Grande, J. (2022). Entrepreneurship and embeddedness: Process, context and theoretical foundations. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 34(3–4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2022.2055152

Locke, K., Feldman, M. S. Golden-Biddle, K. (2015). Discovery, validation, and live coding. Handbook of Qualitative Organizational Research: Innovative Pathways and Methods, 135–167.

Lukeš, M., Longo, M. C. Zouhar, J. (2019). Do business incubators really enhance entrepreneurial growth? Evidence from a large sample of innovative Italian start-ups. Technovation, 82–83 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2018.07.008

Lent, M. (2020). Everyday entrepreneurship among women in Northern Ghana: A practice perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(4), 777–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2019.1672707

McKeever, E., Jack, S., & Anderson, A. R. (2015). Embedded entrepreneurship in the creative re-construction of place. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(1), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.002

Nair, S., & Blomquist, T. (2018). The temporal dimensions of business incubation: A value-creation perspective. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750318817970

Nair, S., & Blomquist, T. (2021). Exploring docility: A behavioral approach to interventions in business incubation. Research Policy, 50(7), 104274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2021.104274

Nicolini, D. (2017). Practice theory as a package of theory, method and vocabulary: Affordances and limitations. In M. Jonas, B. Littig, & A. Wroblewski (Eds.), Methodological Reflections on Practice Oriented Theories (pp. 19–34). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52897-7_2

Nicolopoulou, K., Karataş-Özkan, M., Vas, C., & Nouman, M. (2017). An incubation perspective on social innovation: The London Hub – a social incubator. R and D Management, 47(3), 368–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12179

Ormiston, J., & Thompson, N. A. (2021). Viewing entrepreneurship “in motion”: Exploring current uses and future possibilities of video-based entrepreneurship research. Journal of Small Business Management.

Samra-Fredericks, D. (2003). Strategizing as lived experience and strategists’ everyday efforts to shape strategic direction*. In Journal of Management Studies (Vol. 40, Issue 1).

Sansone, G., Andreotti, P., Colombelli, A., & Landoni, P. (2020). Are social incubators different from other incubators? Evidence from Italy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 158, 120132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120132

Sarason, Y., Dean, T., & Dillard, J. F. (2006). Entrepreneurship as the nexus of individual and opportunity: A structuration view. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(3), 286–305.

Schatzki, T. R. (2001). Practice theory: An introduction. In T. R. Schatzki, K. K. Cetina, & E. von Savigny (Eds.), The practice turn in contemporary theory (pp. 1–14). Routledge.

Schatzki, T. R. (2012). A primer on practices. In J. Higgs, R. Barnett, M. Hutchings, & F. Trede (Eds.), Practice-Based Education: Perspectives and Strategies (pp. 13–26). Sense Publishers.

Schwartz, M. (2013). A control group study of incubators’ impact to promote firm survival. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(3), 302–331.

Scillitoe, J. L., & Chakrabarti, A. K. (2010). The role of incubator interactions in assisting new ventures. Technovation, 30(3), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2009.12.002

Shankar, R. K., & Clausen, T. H. (2020). Scale quickly or fail fast: An inductive study of acceleration. Technovation, 98, 102174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2020.102174

Siebert, S., Wilson, F., & Hamilton, J. R. A. (2017). “devils may sit here:” The role of enchantment in institutional maintenance. Academy of Management Journal, 60(4), 1607–1632. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0487

Sullivan, D. M., Marvel, M. R., & Wolfe, M. T. (2021). With a little help from my friends? How learning activities and network ties impact performance for high tech startups in incubators. Technovation, 101, 102209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2020.102209

Tang, M., Walsh, G. S., Li, C., & Baskaran, A. (2021). Exploring technology business incubators and their business incubation models: Case studies from China. Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(1), 90–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09759-4

Tatli, A., Vassilopoulou, J., Özbilgin, M., Forson, C., & Slutskaya, N. (2014). A Bourdieuan relational perspective for entrepreneurship research. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(4), 615–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12122

Theodorakopoulos, N., Kakabadse, N. K., & McGowan, C. (2014). What matters in business incubation? A literature review and a suggestion for situated theorising. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 21(4), 602–622. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-09-2014-0152

Thompson, N. A., Verduijn, K., & Gartner, W. B. (2020). Entrepreneurship-as-practice: Grounding contemporary theories of practice into entrepreneurship studies. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 32(3–4), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2019.1641978

Thompson, N. A., Byrne, O., Jenkins, A., & Teague, B. (Eds.). (2022). Research handbook on entrepreneurship as practice. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Tuitjer, G. (2022). Growing beyond the niche? How machines link production and networking practices of small rural food businesses. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 00(00), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2022.2062619

van Rijnsoever, F. J. (2020). Meeting, mating, and intermediating: How incubators can overcome weak network problems in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Research Policy, 49(1), 103884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103884

Van Burg, E., Cornelissen, J., Stam, W., Jack, S., Burg, E. Van, Cornelissen, J., Stam, W., & Jack, S. (2020). Advancing qualitative entrepreneurship research: Leveraging methodological plurality for achieving scholarly impact. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, in press, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258720943051

Wang, Z., He, Q., Xia, S., Sarpong, D., Xiong, A., & Maas, G. (2020). Capacities of business incubator and regional innovation performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 158, 120125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120125

Watson, T. J. (2011). Ethnography, reality, and truth: The vital need for studies of “how things work” in Organizations and Management. Journal of Management Studies, 48(1), 202–217.

Welter, F., & Baker, T. (2020). Moving contexts onto new roads: Clues from other disciplines. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(5), 104225872093099. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258720930996

Welter, F., Baker, T., & Wirsching, K. (2019). Three waves and counting: The rising tide of contextualization in entrepreneurship research. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0094-5

Welter, F., Baker, T., Audretsch, D. B., & Gartner, W. B. (2017). Everyday entrepreneurship—A call for entrepreneurship research to embrace entrepreneurial diversity. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(3), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12258

Woolley, J. L., & MacGregor, N. (2021). The influence of incubator and accelerator participation on nanotechnology venture success. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587211024510

Wigren-Kristoferson, C., Brundin, E., Hellerstedt, K., Stevenson, A., & Aggestam, M. (2022). Rethinking embeddedness: A review and research agenda. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2021.2021298

Wigren-Kristofersen, C., Korsgaard, S., Brundin, E., Hellerstedt, K., AgneteAlsos, G., & Grande, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship and embeddedness: Dynamic, processual and multi-layered perspectives. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 31(9–10), 1011–1015. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2019.1656868

Wu, W., Wang, H., & Wu, Y. J. (2021). Internal and external networks, and incubatees’ performance in dynamic environments: Entrepreneurial learning’s mediating effect. Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(6), 1707–1733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-020-09790-w

Yu, S. (2020). How do accelerators impact the performance of high-technology ventures? Management Science, 66(2), 530–552. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2018.3256

Zahra, S. A. (2007). Contextualizing theory building in entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(3), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.04.007

Zahra, S. A., Wright, M., & Abdelgawad, S. G. (2014). Contextualization and the advancement of entrepreneurship research. International Small Business Journal, 32(5), 479–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242613519807

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Erkelens, A.M., Thompson, N.A. & Chalmers, D. The dynamic construction of an incubation context: a practice theory perspective. Small Bus Econ 62, 583–605 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-023-00771-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-023-00771-5

Keywords

- Contextualization

- Practice theory

- Entrepreneurial support organization

- Incubator

- Social entrepreneurship