Abstract

Long-term orientation (LTO) is an essential strategic option for firms to shape their future success, in particular for SMEs which are often submerged by daily operations. Surprisingly, little is known about the underlying personal and contextual drivers of LTO in an SME context. To unravel why some SME entrepreneurs adopt an LTO, while others seem to be stuck in short term and daily operations, we consider the (interacting) impact of both personal and contextual drivers. We carefully select well known drivers for their impact on various other aspects of SME’s LTO: Need for achievement, as a personal driver, and the entrepreneur’s perception of the institutional entrepreneurial support (PIES), as a contextual driver. The latter consists of a regulative, normative and cognitive institutional dimension. Based on a study on 176 SMEs in an emerging country, Indonesia, we confirm that both personal as well as contextual drivers individually and interactively impact an SME’s LTO. Specifically, when highly achievement motivated entrepreneurs perceive that institutional regulations support entrepreneurial activities, they tend to adopt a higher level of LTO. We discuss implications for SMEs and policy makers, and provide suggestions for future research.

Plain English Summary

The inner personality of entrepreneurs and their perception of regulation within a country boost SME’s long-term orientation. This study examines the role of inner personality of entrepreneurs, implicit need for achievement (nAchievement), and their perception of the institutional context of the SME’s long-term orientation (LTO). Introducing a reflective measurement, namely Operant Motive Test (OMT), to measure entrepreneurs’ nAchievement in the entrepreneurship domain, this study reveals that nAchievement and its interaction with the perception of regulations in a developing country, Indonesia, are significantly associated with an SME’s LTO. Our findings support the importance of regulations for SMEs and provide novel insights to the entrepreneurship domain related to the need to consider the entrepreneur’s inner personality as a strong antecedent of entrepreneurial behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

To ensure continued company growth, paying attention to long-term goals is essential (Lumpkin et al., 2010). This is especially the case for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) because compared to their larger counterparts, SMEs tend to be relatively more submerged by daily, short-term operations (Cambra-Fierro & Polo-Redondo, 2008) and are more vulnerable to environmental forces (O’Regan & Ghobadian, 2004). Unlike short-term-oriented firms, firms with a long-term orientation (LTO) have a clear vision of the future and are able to valorize their decisions in the long-term, resulting in increased company performance (Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2006). A strong LTO not only makes firms more effective at reaching their goals but is also a key capability leading to a sustained competitive advantage (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007; Habbershon & Williams, 1999). LTO is especially beneficial for SMEs (Hoffmann et al., 2014; Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2006; Lumpkin et al., 2010) because it safeguards the survivability of the business and, in the case of family-owned SMEs, guarantees a smooth transition of the company to the next generation (Brigham et al., 2014; Gentry et al., 2016). All in all, a strong LTO provides SMEs with a key success factor to compete with their larger counterparts and short-term oriented SMEs (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003; Wilson et al., 2013).

To better understand the drivers of LTO in an SME context, a wide variety of determinants has been examined. Most of these studies focus on organizational (e.g., firm size, organizational capabilities) (Brigham et al., 2014; Polo-Redondo & Cambra-Fierro, 2007) or institutional characteristics (e.g., culture, norms) (Al Omoush et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2008). Only a few empirical studies focus on individual characteristics of the entrepreneur (O’Regan & Ghobadian, 2004), and if they do so, the studied individual-level characteristics are most often closely linked to an organizational setting, like leadership profiles (O’Regan & Ghobadian, 2004). Research that focuses on more abstract and deeply rooted individual-level constructs, like personality profiles, basic motives, or perceptions, almost does not exist (Watson, 2013).

This is unfortunate, particularly because the informal and simple organizational structure that is typical for SMEs (Rauch et al., 2005) makes the SME’s behavior strongly connected to the entrepreneur’s personality (Brammer et al., 2012; Child et al., 2017) and her/his personal perceptions of the outside world (Brouthers et al., 1988). Specifically, since the entrepreneur’s personality influences goal-setting (Wu et al., 2007) and because SMEs are strongly affected by the institutions surrounding them, the entrepreneur’s perception of the prevalent entrepreneurial support in the institutional environment turns out to affect her/his long-term goals and future opportunities she/he sees (Lortie et al., 2019; Sternad & Kennelly, 2017).

This paper follows these arguments and focuses on basic human needs, or motives, as personality constructs (McClelland et al., 1989) and the entrepreneur's perception of institutional entrepreneurial support (PIES) as determinants of LTO. Motives are of particular interest as a long research tradition aims to connect the basic motives of the entrepreneur with a wide spectrum of entrepreneurial behaviors (Omorede et al., 2015; Gielnik & Frese, 2013). However, a consensus on the specific relation between motives and entrepreneurial behavior, including LTO, seems to be lacking (Xue et al., 2021). A plausible reason for this lack of consensus is that most researchers adopt explicit instead of implicit motives (e.g., Chen et al., 2012; Collins et al., 2004; Johnson, 1990; Ryan et al., 2011). Yet, studying many entrepreneurial behavior, including LTO, may benefit from a stronger emphasis on implicit motives, as implicit, rather than explicit motives, seem to be related to many long-term behaviors (Apers et al., 2019; McClelland & Boyatzis, 1982; McClelland et al., 1989; Schultheiss and Brunstein, 2010; Veenstra, 2020; Winter, 1991). Hence, a focus on implicit motives seems to be warranted in studying a company's LTO.

We specifically select need for achievement as a potential motive impacting LTO because it is a well-known determinant of many entrepreneurial activities (Handrito et al., 2020; Pang, 2010). Yet, rather than popularity, our focus on need for achievement is mainly driven by the idea that both need for achievement and LTO are related to the adoption of risk-reducing strategies. As high-need-for-achievement individuals exhibit a greater preference for moderate risks than individuals with low need for achievement (McClelland, 1985, Pang, 2010, Spangler, 1992), adopting strategies with the potential to reduce the risk of high-risk behaviors is of particular interest to them. Adopting a long-term-oriented strategy has the potential to do so (Brigham et al., 2014; Flammer & Bansal, 2017). Put differently, achievement-motivated people prefer to take calculated risks during the decision-making process (Atkinson, 1957; Cooper, 1983; Spangler, 1992), and a LTO may provide them with the conditions that allow them to take calculated risks.

Next to need for achievement, we also include the perception of institutional entrepreneurial support (PIES) as a potential driver of LTO. The reason for the adoption of PIES is twofold. First, we deliberately select to focus on perceptions of institutional entrepreneurial support because entrepreneurial behaviors, including LTO, do not occur in a vacuum. Institutional theory argues that an institution’s normative, cognitive, and regulative surrounding affects entrepreneurial behavior (Gupta et al., 2014; Manolova et al., 2008) including LTO. Specifically, this theory states that the more the surrounding institutions support a certain behavior, the more this behavior will be displayed (Scott, 2005). For example, if a person’s perception is that the surrounding regulations support the establishment of new businesses, s/he may feel confident in the regulative institutional support, which may increase her/his willingness to engage in entrepreneurial activities in the long run.

Second, we include PIES because not only the institutional context itself sets norms and standards of behavior that reinforces certain behaviors and ways of thinking (Valdez & Richardson, 2013), also the way in which these contextual norms and standards are perceived by the individual impacts entrepreneurial behavior, including LTO (Brueckner et al., 2021; Duncan & Peterson, 2010). Also, perceptions interact with and channel the impact of a person’s implicit needs on behavior (Kehr, 2004). Thus adding PIES does not only allow us to examine an additional underlying individual-level construct as a driver of LTO, it also allows us to examine the interplay between the perceptions of contextual drivers (i.e. the institutional entrepreneurial support) and a person’s implicit needs.

We selected Indonesia as our research setting because of its economic significance and relevance for studying SME development (OECD, 2020). More specifically, we tested the relation between the entrepreneurs’ implicit need for achievement, their perceptions of institutional entrepreneurial support, and their SMEs’ levels of LTO on a sample of 176 Indonesian SME owners.

With this research set-up, we offer two overarching theoretical, one methodological, and one practical contribution to the entrepreneurship field. Theoretically, we revisit a well-established concept in the entrepreneurship literature: the need for achievement. We explicitly advocate for a shift from an almost exclusive focus on explicit need for achievement to wider adoption of implicit need for achievement (Baum et al., 2007; Pang, 2010; Wu et al., 2007). In most studies in the entrepreneurship field, the need for achievement is measured through self-administered questionnaires, making it a measure of explicit need for achievement, which is a distinct psychological construct (McClelland et al., 1989, Schultheiss et al., 2009), while the theoretic underpinning often heavily relies on implicit need for achievement theories. This mismatch, of course, often yields unexpected results.

Second, we introduce PIES as a new determinant of LTO and discuss its interaction with need for achievement. We show that LTO is not only related to the entrepreneur's perceptions of institutional entrepreneurial support or the entrepreneur's need for achievement but also to the interplay between both constructs. More generally, we highlight the need to build more complex theories and empirical models to study the underlying psychological drivers of entrepreneurial behaviors.

Methodologically, we specifically focus on implicit needs and select a specific measure to assess the implicit need for achievement of entrepreneurs. We show that introducing concepts and measures that are widely accepted and adopted in psychology – the distinction between implicit and explicit motives and measures – into the entrepreneurship field, is not only relevant but also needed to advance our understanding of entrepreneurial behavior.

Practically, as our empirical study involves SME owners in Indonesia, a large and high-growth economy in Southeast Asia, the results provide insights into the further development of Asian SMEs. What is more, given Indonesia’s rising importance in the global economy (Yiu et al., 2018), our research – even though the a cross-sectional nature of our study refrains us from drawing any causal conclusions – adds insights into global economic development. Also, our results provide evidence that entrepreneurship theories that are mainly developed for, and tested in, Western and highly developed countries can also be applied to Asian emerging economies.

2 Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1 LTO and SMEs

LTO has been studied in many research domains. In marketing, for example, LTO is often used to better understand the formation and evolutions of long-term relationships between a supplier and a buyer (Morgan & Hunt, 1994, Ryu et al., 2007). In general cross-cultural research, Hofstede (1980, 2011) proposes that LTO is a key dimension of a national culture which is formed nationally by shared underlying mechanisms and habits (Wang et al., 2008). Cultural researchers found that these underlying mechanisms may differ between countries. To illustrate, while in Western cultures, LTO is mainly driven by trust and commitment (Morgan & Hunt, 1994), the underlying mechanisms that explain LTO in China are trust and renqing, a typical Chinese cultural value (i.e., the inclusion of human sentiments and feelings in a business setting, also the exchange of favors) (C. L. Wang et al., 2008). Therefore, compared to a Western context, companies in China whose strategic decisions have a long‐term orientation are more likely to develop socially responsible activities as these activities are manifestations of renqing (T. Wang & Bansal, 2012). In this study, and in line with, for example, Zahra et al. (2004), Bearden et al. (2006), and Le Breton-Miller and Miller (2006), we adopt the entrepreneurial viewpoint on long-term orientation. LTO is defined as “the tendency to prioritize the long-range implications and impact of decisions and actions that come to fruition after an extended time period” (Lumpkin et al., 2010, p. 241). We thus consider LTO as a firm-level strategy that reflects the entrepreneur’s preference for long-term (and thus future) successes and achievements (Brigham et al., 2014; Lumpkin & Brigham, 2011).

The way firms see the future determines their strategy and decision-making process. That is, some firms may reinvest a large share of their profits into R&D to anticipate changes in the business landscape, whereas other firms rather invest their profits in consolidating their current state, assuming a status quo in the business environment (Brigham et al., 2014; Cambra-Fierro & Polo-Redondo, 2008). Business practices often show that companies with a long-term focus outperform companies with a shorter time horizon. For example, Samsung’s strong long-term orientation is often seen as a key reason why it could take a significant market share away from its rivals, such as Nokia and Motorola (Evans, 2019).

Given the importance of LTO in understanding business performance, many studies examine its effects and drivers. For example, scholars find that LTO is driven by strategy, leadership, culture, organizational capability (O’Regan & Ghobadian, 2004), ownership, control, knowledge of the business, CEO tenures, considerations for a later generation (Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2006), firm size, and consumer satisfaction (Polo-Redondo & Cambra-Fierro, 2007). Research also shows that a strong LTO is beneficial for companies because it facilitates the maintenance of long-lasting relationships with company stakeholders, which in turn, is considered to be a key success factor for many companies and an important way to achieve a competitive advantage (Polo-Redondo & Cambra-Fierro, 2007). Further, LTO shifts the attention away from quick gains and short-term profits toward future, long-term successes and achievements. A strong LTO also leads to innovation and risk-reducing strategies (Brigham et al., 2014; Flammer & Bansal, 2017). Hence, LTO can be considered as a safeguard for the firm and as a strategy to maintain the competitive advantage of the firm in the future (Brigham et al., 2014; Flammer & Bansal, 2017; Gentry et al., 2016).

Interestingly, compared to large firms, SMEs are mostly associated with a short-term orientation (O’Regan & Ghobadian, 2004) due to more limited resources. The combination of a smaller workforce with an oftentimes dynamic environment urges SMEs to focus on short and daily operations rather than long-term strategies, especially in emerging countries (Covin & Slevin, 1989; Falkner & Hiebl, 2015; Vanderstraeten et al., 2020a, 2020b). This is unfortunate, in particular, because SMEs constitute a very large proportion of firms around the world and are foundational for economic development (Block et al., 2007; WTO, 2016). They provide a livelihood for many workers and families in emerging countries (OECD, 2017, 2020), where they are often the last resort for the poor in the form of small, less-formal jobs (Tambunan, 2008; World-Bank, 2020). A better understanding of the antecedents of long-term orientation might provide opportunities for the government to develop policies aimed at stimulating SMEs’ long-term orientation, as such positively impacting company growth and economic development at large.

However, even though SME behavior is – due to its informal and simple organizational structure (Rauch et al., 2005) – deeply rooted in the entrepreneur’s personality (Brammer et al., 2012; Child et al., 2017) and her/his perceptions (Brouthers et al., 1988), there are only a few empirical studies focusing on the role of individual-level characteristics on a firm’s LTO (Watson, 2013; Zheng et al., 2020). The current paper adds to this literature stream. As such, we follow researchers such as Handrito and colleagues (2020, 2021), Hermans and colleagues (2017), Slabbinck and colleagues (2018), and Xue and colleagues (2021), who recently stressed the importance of such individual-level characteristics in relation to an SME’s orientations, goals setting, engagements, and performance.

2.2 Human Basic Needs and LTO

Personality is a multi-faceted concept with at least three distinguishable aspects: values, traits, and motives (Hofer et al., 2008; Winter et al., 1998). This study focuses on motives because they are capable of answering “why” a person’s behavior is performed (Engel et al., 2002). Because people initiate and persist in behaviors that provide satisfaction, as well as behavior that prevents dissatisfactions and disappointments while also fulfilling human basic needs (McClelland & Franz, 1992), we posit that one’s motives may determine whether or not they opt for LTO, as well as the extent to which they opt for LTO.

Human basic needs theory posits that motives are formed in early life through (pre-linguistic) affective learning experiences (Schultheiss & Kollner, 2014; Schultheiss & Schultheiss, 2014). That is, a person’s behavior in her/his later life is influenced by the treatment given by her/his caregiver during her/his childhood (Bender & Woike, 2010). In the case of positive affective learning experiences, an individual is, in her/his later life, more likely to react automatically and more favorably to a situation that calls upon the former learning experience (McClelland et al., 1989). To illustrate, toddlers who were motivated to take care of themselves (e.g., eating without help, applauded when doing things on their own) will, later in their life, also get satisfaction when they manage to do (complicated) things on their own (McClelland & Pilon, 1983). Put more generally, if a person’s orientation, selection, and continuation of behavior are in line with her/his human basic needs, she/he will get satisfaction and experience greater well-being (Bender & Woike, 2010; McClelland, 1987).

Interestingly, human basic needs theory makes a clear distinction between explicit and implicit needs (McClelland et al. (1989). Explicit needs are related to controlled or conscious information processing and propositional reasoning, while implicit needs are related to automatic or non-conscious information processing (McClelland et al., 1989; Schultheiss & Brunstein, 2010; Slabbinck et al., 2018). Importantly, explicit and implicit needs operate independently from each other, each influencing different types of behavior (Kollner & Schultheiss, 2014; Perugini et al., 2010). That is, explicit needs predict immediate and short-term behaviors that are subject to conscious thought and deliberation, such as self-reflective appraisals, the judgment of others, and deliberate choices, whereas implicit needs predict long-term and spontaneous effort-related task performance (Perugini et al., 2010; Schultheiss & Brunstein, 2010). Because LTO, by definition, is a construct that is related to long-term and future behaviors and because the execution of long-term goals requires a lot of effort and persistence, we focus on implicit needs rather than on explicit needs (Bernecker & Job, 2010; Schultheiss & Brunstein, 2001; Slabbinck et al., 2011).

Further, implicit needs theory is distinguished into three different needs: the need for power (nPower), the need for affiliation (nAffiliation), and the need for achievement (nAchievement) (McClelland et al., 1989). nAffiliation refers to the need or desire to achieve, maintain, or restore positive relationships with others (Heyns et al., 1958). nPower relates to the need to impact others and the desire to be seen and recognized by others (Winter, 1973). Finally, nAchievement is a motive that energizes individuals to engage in challenging and risky tasks that improve their performance or their own standards of excellence (Litwin, 1966; McClelland, 1965; Schultheiss & Brunstein, 2010).

In general, the need for achievement motivates people to work independently and to be responsible for their own performance (Atkinson & Litwin, 1960; de Charms et al., 1968; Litwin, 1966). We focus on nAchievement because it is linked to entrepreneurial activity in general (Collins et al., 2000; Hansemark, 2003; McClelland, 1965; Ryan et al., 2011; Sagie & Elizur, 1999) and long term business performance in specific. For example, McClelland (1961) shows that on a national level, nAchievement predicts long-term entrepreneurial success and the choice to become an entrepreneur. Also, on an individual level, McClelland (1965) illustrates that students high in nAchievement are more likely to pursue an entrepreneurial occupation in their later life. In addition, Ramsay et al. (2017) show that nAchievement scores of owner-managers and top executives predicted increased hiring, output, and investment in their companies over time as well as future decision-making. In line, Slabbinck et al. (2018) demonstrate that start-ups grow faster when they are managed by achievement-motivated entrepreneurs. Recently, Handrito et al. (2020) show that SMEs owned by entrepreneurs with high nAchievement are associated with a higher degree of internationalization.nAchievement is also closely linked to many aspects that are connected to LTO. Miller and Toulouse (1986) found that nAchievement is related to a preference for formal and sophisticated structures. They also show that nAchievement motivated CEOs are more ambitious and desire to have as much control over their environments as possible. They do not want anything left to chance. Thus they carefully analyze situations so that they can proactively manipulate rather than having to react to their customers and competitors. nAchievement driven entrepreneurs also habitually spend their time thinking about doing things better (Atkinson, 1958). All these examples illustrate that nAchievement motivated persons in general and entrepreneurs, in particular, put a lot of effort into activities to mitigate and minimize future risks. LTO is also related to the adoption of risk-reducing strategies (Brigham et al., 2014; Flammer & Bansal, 2017). That is, an increase in time horizon activates a person’s awareness of risks and hence leads to greater consideration of risk in decision-making (Flammer, 2013). As high-need-for-achievement individuals exhibit a greater preference for moderate risks than individuals low on need for achievement (McClelland, 1985, Pang, 2010, Spangler, 1992), adopting strategies with the potential to reduce the risk of high-risk behaviors are of a particular interest for them. Put differently, achievement motivated people prefer to take calculated risks during the decision-making process (Atkinson, 1957; Cooper, 1983; Spangler, 1992), and an LTO may provide them with the conditions that allow them to take calculated risks. Also, as LTO requires entrepreneurs to have a long-term commitment to achieve long-term and challenging goals, which is consistent with the activities that energize and motivate a person’s need for achievement, we hypothesize that:

-

H1: nAchievement positively relates to the level of the SME’s long-term orientation

2.3 Perception of Institutional Entrepreneurial Support and LTO

Institutionalists believe that the development of entrepreneurial activities is heavily affected by the surrounding institutions (Bosma et al., 2018; Schmitz et al., 2016; Urbano et al., 2019). The strength of the institutional entrepreneurial support that surrounds the companies is heavily related to the entrepreneurial activity and performance of the company and the country in general (Bowen & De Clercq, 2008; Walter & Block, 2016). Valdez and Richardson (2013) argue that the institution (Busenitz et al., 2000) sets norms and standards of behavior, reinforcing certain behaviors and ways of thinking of society in general and entrepreneurs in specific. The institution is also seen as a shared value that governs social and economic behavior and exchange in a certain country (Chiles et al., 2016; Gupta et al., 2014).

Countries with a high level of institutional entrepreneurial support tend to have a high level of entrepreneurial activity compared to countries with low-level entrepreneurial support (Dehghanpour Farashah, 2015; Valdez & Richardson, 2013). This is because residents living in a high-level entrepreneurial support country feel that the institutions they rely on and the shared values they live with support entrepreneurial activities. A well-elaborated system of incentives and rewards, combined with supportive social norms and cultural values, substantially decreases the risk of starting and expanding a business (Bruton et al., 2008). Importantly, institutional support does not only explain differences in entrepreneurial activity between countries (Spencer & Gómez, 2004; Valdez & Richardson, 2013) but also the perceptions of institutional entrepreneurial support explain individual differences in entrepreneurial activity (Gupta et al., 2014; Manolova et al., 2008; Urbano et al., 2019). Roxas and Coetzer (2012), for example, show that the entrepreneur's perception of the country’s institutional entrepreneurial environment is related to the environmental sustainability orientation of her/his firm. Also, Urban and Kujinga (2017) demonstrate that perceived institutional support is positively associated with the entrepreneur's social entrepreneurial intention. Recently, Xiao et al. (2022) show that the level of institutional support in China positively affects a firms’ entrepreneurial mindset.

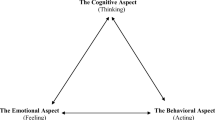

Yet, important to note is that the term “institution” is a multidimensional construct comprising three dimensions: a regulative, normative, and cognitive dimensions (Bruton et al., 2010; Busenitz et al., 2000), which are all related to entrepreneurial activities (Parboteeah et al., 2008; Quer et al., 2019; Valdez & Richardson, 2013; Vanderstraeten, et al., 2020a, 2020b; Zhang et al., 2011). This study builds upon these findings and investigates the role of the entrepreneur’s perception of each of the institutional dimensions on her/her SME’s LTO.

2.4 The Regulative Institutional Dimension and LTO

The regulative dimension refers to the formal structure of the laws, economic policies, formal regulations, and the role that the government takes in assisting entrepreneurs in each country (Busenitz et al., 2000; Manolova et al., 2008). Regulation consists of rules, monitoring, and sanctions to make sure that the policy is obeyed (Veciana & Urbano, 2008). Thus, they impact the entrepreneur’s future actions (Valdez & Richardson, 2013). A good regulative framework facilitates the establishment of a long-term business strategy (Veciana & Urbano, 2008) because it secures the legitimacy for the future survival of the business (Bruton et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2017). However, if entrepreneurs perceive that the regulative framework is weak — for example, if it does not equally support all companies and only accommodates the interests of a limited number of stakeholders — then business uncertainty and risks are too high, which limits the possibility to establish a long-term business strategy. Therefore, the perception that institutions strongly support regulations is essential for promoting LTO. In sum, when entrepreneurs perceive that regulations support businesses and reduce uncertainty (Bylund & McCaffrey, 2017), people will feel confident in the regulative environmental support which triggers their willingness to engage in entrepreneurial activities in the long run and set conditions that favor the development long-term goals. Empirically, on a country level, strong supportive regulations in OECD countries indeed foster long-term investments and economic growth (Wehinger, 2011). Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

H2a: The entrepreneur’s perception of the supportiveness of institutional regulations is positively related to the SME’s long-term orientation.

2.5 The Normative Institutional Dimension and LTO

The normative dimension covers the shared values of society and involves social norms, values, beliefs, and assumptions about humans and how to behave in society (Bruton et al., 2010; Kostova, 1997), including religion (Assouad & Parboteeah, 2017; Parboteeah et al., 2008). The normative dimension defines how entrepreneurial activities are perceived in society (Busenitz et al., 2000; Su et al., 2017). Interestingly, even though the normative dimension is less formal, it is well-accepted as legitimate (Doh et al., 2009), tends to be stable over time, consistent (Hitt, 2016), and is difficult to change (Ahlstrom & Bruton, 2010). In addition, because of its informality, the normative value is well-developed and an important institutional pillar in emerging economies (García-Cabrera et al., 2016), where cultures and norms are often turned into a social obligation (Valdez & Richardson, 2013).

Good institutional entrepreneurial support constitutes a society that provides easy coordination for anyone who needs detailed information and knowledge to determine her/his future actions (Gupta et al., 2014). A culture that perceives entrepreneurship as a respectable career, or put differently, a culture with a supportive entrepreneurial normative dimension, appreciates risky behaviors, such as the establishment of a new venture, and constitutes a fruitful environment for entrepreneurial activities (Bowen & De Clercq, 2008; Bruton et al., 2010). Such a supportive social environment may also facilitate the execution of a long-term strategy (Fitzsimons & Shah, 2008), and people’s motivation to pursue their long-term goals is most likely higher in such environments (Fitzsimons & Finkel, 2010; Laurin et al., 2011). A typical Chinese cultural value that is closely related to the notion of a supportive environment is renqing. Empirically, C. L Wang et al. (2008) demonstrate that renqing is positively associated with the long-term orientation of Chinese business-to-business relationships. In sum, if an entrepreneur perceives that she/he is surrounded by a society that embraces entrepreneurial behavior and where achieving a long-term entrepreneurial goal is seen as something to be proud of, it is more likely that his/her business will have a long-term orientation. Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

H2b: The entrepreneur’s perception of the supportiveness of the social (normative) environment is positively related to the SME’s long-term orientation.

2.6 The Cognitive Institutional Dimension and LTO

The cognitive dimension is defined as “the knowledge and skills possessed by the people in a country pertaining to establishing and operating a new business” (Busenitz et al., 2000:995). It also refers to social knowledge shared by people (Veciana & Urbano, 2008). Manolova et al. (2008) perceive the cognitive dimension as everything that is learned through social and formal interactions by living and growing up in society. It is formed through education and training, then it turns into a belief in the expected standard of behavior, in this case, entrepreneurial behavior. The cognitive dimension construct is closely related to both the cultural as well as the individual characteristics of the entrepreneur and, in general, operates at the individual level in terms of culture and language (Bruton et al., 2010).

A growing body of literature demonstrates a positive relation between knowledge, cognitive resources, and an orientation focusing on the future. A meta-analysis, for example, shows that the tendency to prefer smaller, sooner rewards to larger, later ones, also known as delay discounting, is related to cognitive ability, with better performance on measures of intelligence and cognitive control predicting reduced discounting rates (Shamosh & Gray, 2008). Also, compared to new and inexperienced managers, well-established and experienced (thus, knowledgeable) managers are more likely to install and instigate long-term goals in their ventures (Peng & Shekshnia, 1993; Welter & Smallbone, 2011). In a similar vein, Miller and Xu (2020) find that the level of education of the CEO positively corresponds to their LTO strategy. Finally, Busenitz and Lau (1996) find a direct relation between entrepreneurial cognition and a longer time horizon. These examples strongly hint toward the idea that in an environment in which entrepreneurial knowledge thrives, a longer time horizon is more prevalent. Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

H2c: The entrepreneur’s perception of the entrepreneurial knowledge in its surrounding is positively related to the SME’s long-term orientation.

2.7 Moderating Effects of the Perceived Institutional Entrepreneurial Support

In this section, we argue that strong perceived institutional entrepreneurial support may create a business environment that is especially attractive for the needs of achievement-motivated entrepreneurs. Need for achievement motivated people specifically tend to engage in challenging tasks or activities that have a moderate level of risk, giving them the opportunity to succeed or to master those tasks (McClelland et al., 1953; Pang, 2010). Moreover, they dislike activities that threaten their opportunities (Brody, 1963; Chen et al., 2012; Handrito et al., 2020), such as corruption and favoritism while doing business. A perception of strong institutional entrepreneurial support may reduce the perceived level of risk that is typically associated with entrepreneurial activities (Bowen & De Clercq, 2008), thus reducing the uncertainty in business to an acceptable level for entrepreneurs seeking moderate risk levels.

Specifically, good business regulations increase transparency and reduce the risk that goes with becoming an entrepreneur to a moderate level. Thus, a strongly regulated business environment may be particularly attractive for achievement-oriented entrepreneurs. We expect that a strong regulative framework provides the necessary condition for a highly nAchievement motivated entrepreneur to orient her/his business towards long-term success. Similarly, if the surrounding environment allows people to take risks and does not blame people if they fail with their business (i.e., a strong normative dimension) or if the environment provides ample opportunities to train and acquire the cognitive capabilities needed to be a successful entrepreneur (i.e., a strong cognitive dimension), this may particularly stimulate nAchievement motivated entrepreneurs to orient their business to long-term successes. Hence, we hypothesize:

-

H3a: An SME managed by a high nAchievement motivated entrepreneur will tend to be more long-term oriented if the entrepreneur perceives that the institutional regulations support the businesses.

-

H3b: An SME managed by a high nAchievement motivated entrepreneur will tend to be more long-term oriented if the entrepreneur perceives that the surrounding institutional norms support the businesses.

-

H3c: An SME managed by a high nAchievement motivated entrepreneur will tend to be more long-term oriented if the entrepreneur perceives that she/he is capable of accessing knowledge that supports the businesses.

3 Methodology

3.1 Data Collection

The data is part of a larger study on SME behavior in a developing country; Indonesia. We recruited SME owners that are listed in the database of the Indonesian East Java Bureau of SME Affairs in 2017 and extended this sample by means of snowballing (see further). We selected the province of East Java because of its relatively high economic growth (5.45 percent) compared to the national average (5.07 percent) in 2017 (BPS, 2018a, 2018b). The East Java Province is also representative of Indonesia’s general economic and business activities.

In Indonesia, there are several definitions of an SME. According to Law n° 20/2008 regarding Micro, Small, and Medium-sized Enterprises, a small enterprise is defined as a company with annual sales between 300 and 2.500 million Rupiah (i.e., between 20,000 and 160,000 Euro) as well as an annual net worth between 50 and 500 million Rupiah (i.e., between 3,200 and 32,000 Euro). A medium-sized enterprise is a company with annual sales between 2.5 and 50 billion Rupiah (i.e., between 160,000 and 3,200,000 thousand Euro) and annual net worth between 0.5 and 10 billion Rupiah (i.e., between 32,000 and 645,000 Euro). The Bureau of Statistics in Indonesia (BPS) defines SMEs based on the number of employees: a company with 5–19 employees is a small enterprise, and one with 20–99 employees is a medium-sized enterprise. Finally, the Central Bank of The Republic of Indonesia defines small and medium-sized enterprises as companies with maximum assets worth 600 million Rupiah, excluding land and buildings (i.e., 38,000 Euro), and annual sales less than 1 billion Rupiah (i.e., 65,000 Euro). We combined these prerequisites and only selected companies fitting the most ‘strict’ SME conditions, in the case that two different categorizations are possible. The reason is simple: given that we examine personality characteristics, it is important not to include large firms. Thus, the stricter the definition of an SME, the better.

The database comprises 627 SMEs that received incentives, participated in workshops, or joined networking events organized by the government to stimulate firm internationalization. Data collection comprised three stages: first, we contacted all 627 SMEs to ensure that they were eligible and willing to participate in our study. Second, we scheduled an on-site visit to collect the data. Third, ten well-trained surveyors visited the SMEs for interviewing and data collection. To avoid miscommunication, the surveyors contacted the SMEs one week prior to the on-site visits.

The data collection took place between April and September 2018, well before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. On average, each on-site visit took between 60–75 min, including the introduction, the interview, and breaks to minimize fatigue (Olson, 2016; Rubin & Rubin, 2011). We opted for on-site data collection because this ensured that the right person participated in the study and that the participants correctly interpreted the questions. Moreover, face-to-face data collection provides participants with the possibility to ask for clarification of the questions, which reduces ambiguity (Malhotra et al., 2017).

We contacted 485 SMEs by phone and 142 SMEs by mail. We only mailed companies when their phone number was not mentioned on the contact list. We received 113 positive responses out of the 485 calls. From the 142 mails, 18 mails were returned due to invalid or changed addresses and 13 SMEs responded positively. This resulted in an overall response rate of 20.1 percent (126 respondents). This response rate is acceptable and in line with recent studies in emerging Southeast Asian economies where participation in on-site data collection is relatively low and where a tradition of participation in surveys and research is not well established (Isobe et al., 2000; Pangarkar, 2008; Pangarkar & Klein, 2004). Reasons for not participating were unmotivated rejections to participate (184 SMEs), the enterprises no longer existing (78 SMEs), and no answer or reply after several attempts (239 SMEs).

As the database contains only the company name of the SME, the name of the owner, the address, the phone number, and the email address, we cannot check non-response bias by comparing, for example, the age, gender, and performance indicators between the respondents and their SMEs and the non-respondents and their SMEs. However, as most of our participants were recruited by phone, we asked SME owners who rejected the survey invitation or who withdrew their participation why they did so. None of the reasons indicated that a particular type or niche of SME owners refrained from participation, minimizing the impact of non-response bias on our results.

While the surveyors were in the field visiting the participating companies, they were instructed to search for eligible companies that were not listed in the database of the East Java Bureau of SME Affairs. As such, we also relied on snowball sampling, allowing us to increase the representativeness of our sample. In Indonesia, many SMEs are not listed because they do not formally register themselves, and many do not attend government events (Mourougane, 2012). This snowball sampling strategy resulted in an additional 52 companies yielding a total sample of 178 SMEs. Out of these 178 responses, two participants requested to withdraw their data, resulting in a final sample of 176 cases. The demographic characteristic of SME respondents is presented in Table 1.

To minimize response bias, we instructed respondents that there are no “right” or “wrong” answers and assured them that their personal identity would be protected and used for academic purposes only (Francioni et al., 2015). To confirm that there are minimal differences between the sample that originates from the database of the East Java Bureau of SME Affairs and the sample obtained through snowball sampling, we conducted independent sample t-tests on their level of internationalization (t = -1.968, df 174, sig 0.051), the number of employees (t = -3.034, df 174, sig 0.003), profit (t = 0.446, df 161, sig 0.656), age of the entrepreneur (t = 0.646, df 174, sig 0.519), and gender (Chi2 = 0.040, sig 0.862). Even though we found a significant difference in the number of employees, the results indicate that the bias that may arise from the two groups we investigate is minimal. As we mainly focus on individual-level characteristics, the difference in the number of employees, a firm-level characteristic, should have a minimal effect on the outcomes of our study. Yet, we added the number of employees as a control variable to our models (see below).

3.2 Measurement Instruments

The implicit need for achievement is measured using the Operant Motive Test (OMT: Kuhl & Scheffer, 1999). The OMT is a reliable and valid measure of implicit need for achievement (Baumann et al., 2005; Kazen & Kuhl, 2011; Schüler et al., 2015). In addition, the OMT works well with the backgrounds and abilities of our respondents. As many respondents are middle and low-educated people who are not familiar with writing long responses to survey questions, techniques that require long and well-elaborated responses are less suited. Unlike other motives measurement techniques, such as Picture Story Exercise (PSE) (Schultheiss & Brunstein, 2010), OMT only requires short answers. Moreover, many of our respondents have limited experience with computers, making digitalized assessment methods such as the Brief Implicit Association Test (BIAT) (Slabbinck et al., 2018) also less suitable.

To complete the OMT, participants were exposed to 15 schematic drawings (see Fig. 1 for an example), one at a time, and were asked to write down in a short form (i.e. a short sentence or some keywords) their spontaneous associations to the following four questions: (1) What is important for the person in this situation and what is the person doing?; (2) How does the person feel?; (3) Why does the person feel this way?; and (4) How does the story end?

The OMT drawings are selected and validated in such a way that the responses are indicative of the participant’s inner, underlying motives (Scheffer et al., 2003; Schüler et al., 2015). For example, if the drawing depicts a man climbing a mountain, the participant can either think that “reaching the top, not quitting” is important for the man in the drawing or that “climbing the mountain faster than anyone else” is the main driver of that man. In the first case, the answer represents the need for achievement, whereas in the latter case, the story instead represents another motive: need for power (Kuhl & Scheffer, 1999).

To construct the individual nAchievement scores, three well-trained coders followed the guidelines from Kuhl and Scheffer (1999). The manual provides strict guidelines on how answers need to be scored. Each picture was scored 1 (one) if the response contained strong references to any of the five themes that are indicative of the specific motive (nAchievement) and scored 0 (zero) if no reference to a specific motive was present. The inter-rater reliability amongst three coders was high (α = 0.975).

We measured the perception of institutional entrepreneurial support by adopting the Country Institutional Profile scale of Busenitz et al. (2000). This 13-item scale is the default method to measure the perception of the institutional environment and has been applied in many studies in various countries (Gupta et al., 2014; Manolova et al., 2008; Parboteeah et al., 2008). The scale consists of three dimensions: regulative (5 items), normative (4 items), and cognitive (4 items). We used a four items long-term orientation (LTO) scale of Wang and Bansal (2012), which is inspired by the futurity concept of Venkatraman (1989). We also included several control variables. We included gender (0 = Female, 1 = Male) and education (0 = Low & Middle, 1 = Higher) because Parboteeah et al. (2008) show that gender and education affect the relationship between the institutional profile and entrepreneurial behavior. We divided education into dichotomous categories because the behavioral difference between higher (i.e., university) and lower educated people are large in Indonesia. Next to gender and education also the age of the owner, age of the firm, size of the firm (based on the number of employees), and sector of the industry (1 = art and handicraft 0 = others) are included as control variables because they may impact a firm’s strategic options (Cavusgil & Naor, 1987; Hsu et al., 2013).

Because we only relied on a single source of information (that is, the entrepreneur), common method bias may be a concern. In order to prevent common method bias, we used different formats to assess our study variables: (a) an open-ended question for the assessment of implicit motives (the Operant Motive Test, see further) and (b) a five-point Likert scale to assess the perception of institutional entrepreneurial support (PIES), and long-term orientation (LTO). Using different measurement formats reduces the likelihood of common method variance bias (Chang et al., 2010). Moreover, we also instructed participants to take a short break during the survey to avoid fatigue. This also increases the temporal separation of items, reducing a participant’s tendency to use the previous answer for the next section (Podsakoff et al., 2012).

To validate our measures, we first subjected all Likert-scale items to a confirmatory factor analysis with varimax rotation and maximum likelihood with intended to four variables; LTO, Regulative, Normative, and Cognitive. We decided to omit the regulative item with the negative factor loading (Reg 2) and reran the factor analysis. We then also examined cross loading factors amongst those items and found that there is a minor issue between item on cognitive (Cog4) with normative variable. The resulting factor loadings are presented in Table 2, along with the composite reliability scores, Cronbach Alpha values, and the Average Variance Extracted scores. All statistics indicate that the measured constructs were reliable (Hair, 2010).

Next to the procedural precautions, we also undertook several statistical tests to check (ex-post) for common method bias. First, a single factor test shows that the extraction of total variance explained by one factor is 38.4%. Even though this value is below the minimum level (50%) for a bias in the estimates of the relationship between our constructs of interest (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986), we explored the potential bias that stems from the usage of common methods further by means of a series of Confirmatory Factor Analyses, using the Lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012). The results of these CFAs showed that linking each variable to a single construct, a common method factor, rather than to their intended theoretical constructs resulted in a significant drop in model fit (Podsakoff et al., 2003, 2012) \(\Delta {}^{2}=373.66, \Delta df=6, p<.0001\), suggesting that common method bias is minor issue in our analyses. Additional tests on the outcomes of the CFAs showed that the heterotrait-monotrait criterion (HTMT) and the Fornell and Larcker criterion are both met, providing further evidence for discriminant validity (see Tables 3 and 4). For each construct, individual scores were calculated as mean scores of the corresponding scale’s individual items.

4 Results

In our sample, the majority of SMEs are led by older people, and 75% of the firms has been in business for more than 11 years old (see Table 1). Moreover, the majority of our respondents have a low to middle educational background. These data are in line with Indonesian official business statistics (BPS, 2018a).

Table 5 shows the correlations among the study variables and indicates that the implicit need for achievement and the three dimensions of PIES are significantly and positively correlated with LTO. Yet, we do not find significant correlations between nAchievement and the PIES dimensions. To confirm these results, we further performed a series of hierarchical OLS regressions. The results are presented in Table 6. In the first model, Model 0, we regressed LTO on the control variables. We then added nAchievement in Model 1 and the three PIES dimensions in Model 2. We followed this approach because the correlations between the three PIES dimensions are relatively high (see Table 5). We finally added the interaction terms of nAchievement with each of the PIES dimensions in Model 3. Compared to Model 2, the addition of the interaction terms in Model 3 increased the Adj R2 with 1.2% into 27.1% with F = 6.006, sig 0.000. The negative effect of the age of the firm indicates that young SMEs tend to be more long-term oriented compared to old SMEs.

Further, Models 1, 2 and 3 portray positive and significant associations between nAchievement and LTO. These results provide support for H1. Model 2 indicates that amongst the three PIES dimensions, the regulative and normative dimensions have a (close to) significant and positive relationship with LTO whereas the cognitive dimension is not significantly related to LTO. Model 2 also indicates that it is important to include all dimensions of the PIES construct in the analysis. Even though only H2a and H2b are supported with respect to H2a is sig at < 0.10. Contrary to our expectation and based on the results reported in Model 3, with moderation effects, we only find a significant moderating effect of the regulative dimension on the relationship between nAchievement and LTO. Therefore, H3a is supported, while H3b and H3c are not supported.

To further test the moderating effect of the regulative dimension, we performed a simple slope analysis (Hayes, 2017) and plotted the interaction in Fig. 2. The result shows that all interactions are significant at any level of the regulative dimension: low (Mean—1SD): t(172) = 0.33, p = 0.014, medium (Mean): t(172) = 0.40, p = 0.01, and high (Mean + 1SD): t(172) = 0.47, p = 0.008.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

The results of our study clearly indicate that goal setting is associated with the entrepreneur’s personality (Brammer et al., 2012; Child et al., 2017) and her/his personal perceptions (Brouthers et al., 1988). More specifically, the positive and significant relation between nAchievement and LTO indicates that nAchievement, which is a deeply rooted entrepreneurial motive, plays an essential role in long-term business behavior of SMEs, as such, supporting McClelland’s (1965) and Pang’s (2010) findings. Our findings also support the idea that the perception of the institutional context is not only related to the LTO of an SME, but also that these institutional perceptions interact and channel the impact of implicit needs on behavior, in our case, LTO (Brueckner et al., 2021; Duncan & Peterson, 2010).

Our findings supplement the literature in several ways. First, we contribute to the need for Achievement literature, both in business as well as in psychology research. Our results support the general idea that nAchievement is strongly associated with entrepreneurial orientations, goals, and behaviors (Handrito et al., 2020; Sagie & Elizur, 1999; Wu et al., 2007; Xue et al., 2021). Previous research already showed that nAchievement is linked to several aspect that are connected to LTO, like risk-taking (McClelland, 1985; Pang, 2010; Spangler, 1992). Our research extends these findings and shows that the entrepreneur’s level of nAchievement is directly linked to the time orientation of her/his business.

Second, by introducing PIES as new determinant of LTO, we also add to institutional theory (Gupta et al., 2014; Manolova et al., 2008). At least in the scope of SMEs, we show that perceptions of the firm’s surrounding context (i.e., PIES) are related to the firm’s strategic orientation. Overall, our findings shed more light on the complex relationship between perceived institutional entrepreneurial support (PIES) and indices of entrepreneurial orientations and behaviors. While we expected direct and positive relations with LTO for all three dimensions of PIES, we only found direct and positive relations for the perceptions of the regulative and the normative dimension, but not for the cognitive dimension. Perhaps unintendedly, our results confirm previous research in which results do not point towards a univocal effect of PIES. For example, in Parboteeah et al.’s (2008) large country study on the effects of the cognitive, normative, and regulative institutional dimensions on traditional gender role attitudes of managers, only the normative dimension seems to be related to the managers' traditional gender role attitudes. In addition, Bowen and De Clercq (2008) find that regulations are negatively related to high-growth entrepreneurial activity, and Valdez and Richardson (2013) find in multi-national and macro-level entrepreneurship studies that there is only a positive and significant relation between the normative and cognitive dimensions and entrepreneurial opportunity-based activities.

Our findings also support the idea that the perception of the institutional context interacts and channels the impact of implicit needs on behavior (Brueckner et al., 2021; Duncan & Peterson, 2010). We theorize and empirically show that LTO is a complex firm-level behavior which is related to deeply rooted individual characteristics (i.e. motives) and perceptions of the firm’s surrounding context (i.e., PIES). We go beyond most previous research by illustrating that these individual-level characteristics do not operate in a vacuum but interact with each other. More specifically, the significant moderation of the perception of the regulative dimension on the relationship between nAchievement and LTO shows that the entrepreneur’s perception of stimulating entrepreneurial regulations plays an important role in the long-term orientation of the country’s entrepreneurial companies. We also expected positive interactions between nAchievement and the normative and cognitive dimensions. The absence of these interactions further confirm that the different dimensions of PIES do not have univocal relations with behavior, and hint toward other societal, contextual and cultural variables that intervene with the PIES dimension.

A plausible explanation for these mixed results, is the cultural context of Indonesia. Since the start of the reform era in 1998, business regulations and other entrepreneurship-related regulations have been improved. The improvements on the (perceptions of the) regulative dimension is, for example, reflected in Indonesia’s rank on the World Bank Ease of Doing Business Index which has increased from 91 out of 189 in 2016 to 73 out of 190 countries in 2020. During the same era, the entrepreneurial activity and perceived opportunity rates also increased in Indonesia (GEM, 2021). According to our theorizing, the improved perception of the regulative institutional environment may thus have alleviated the perceived risk level which should have stimulated entrepreneurs to set long-term objectives, and this especially among nAchievement motivated entrepreneurs.

The cultural context may also explain the non-significant moderation effect of the perceived normative dimension on LTO. That is, choosing an entrepreneurial career has a negative connotation in Indonesia. As in many developing countries, being an entrepreneur in Indonesia is often the result of an imperfect formal workforce market structure (Bruton et al., 2012; OECD, 2018). Entrepreneurship is often and generally considered to be a temporal choice; individuals choose an entrepreneurial career to deal with an economically difficult situation and are expected to switch to a civil servant or other formal jobs from the moment their personal economic situation allows them to do so. In other words, in a country like Indonesia, being an entrepreneur is not one-on-one related to the pursuit of personal ambitions and innovation. This might explain why we do not find an interaction effect between nAchievement motivated owners and the perceived normative institutional dimension when dealing with LTO. A likewise reasoning holds for the absence of an interaction between the cognitive PIES dimension and nAchievement. At the time that the majority of our respondents attended primary and secondary school access to education was often restricted, and entrepreneurship-related topics did not receive primordial attention (GEM, 2018). This limited entrepreneurship-related knowledge may explain why the cognitive dimension is not directly translated into the SMEs’ LTO and why there is no interaction effect between nAchievement motivated SME owners and the entrepreneurial knowledge prevalent in society-at-large. All in all, our mixed results may thus be interpreted as a strong call to introduce more complex models to study LTO and many other entrepreneurial outcome variables.

Lastly, the theoretical advancements could not have been made without the research methods we used. For the assessment of nAchievement, we introduced the OMT, a novel method for the assessment of the implicit need for achievement. However, the OMT is, and similar to most other implicit measures, quite labor intensive, both from a participant’s and a researcher’s point of view. This may hamper further applications of this and other implicit measures. However, as our results would most likely not have been found if we relied on traditional self-report measures, also novel and more efficient implicit measures could be adopted (see e.g., Slabbinck & Spruyt, 2022). Thus, we hope that our approach will inspire other researchers to use our adopted and other novel methods for the assessment of implicit needs and other implicit personality constructs (see, e.g., Slabbinck et al. (2018), Slabbinck and Spruyt (2022), Uhlmann et al. (2012) or Bing et al. (2007) for overviews). Also regarding the assessment of the institutional country profiles, we show that Busenitz’ institutional entrepreneurial scale (2000) is not only useful for studying differences in entrepreneurial activities between countries, but also within a country, on an individual level and using it as a perceptional measure of the prevalent entrepreneurial support in the institutional environment. We also show that this scale is applicable in developing and emerging economies such as Indonesia. This finding is in line with Busenitz et al. (2000), Manolova et al. (2008), and Gupta et al. (2014), who apply the institutional entrepreneurial support scale to study behavioral and/or perceptual differences between and within emerging countries in Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Hungary, Latvia) and four Rapid Evolving Major Economies (REME) (Brazil, China, India, and South Korea).

Our study has also practical implications for policymakers and institutions that aim to improve the entrepreneurial mindset in their country. Our results clearly indicate that the entrepreneur’s personal motives and perceptions of institutional entrepreneurial support must be taken into account in order to foster LTO. Hence, policymakers and other institutions, such as schools and universities, should not only increase their efforts to strengthen the institutional entrepreneurial profile but they should also take care of how these efforts are perceived by potential and current entrepreneurs. Effective communications and training programs may be helpful from that perspective.

Of course, our study is not flawless. First, our study is cross-sectional. Thus, we cannot claim any causal relationship among the variables. A larger sample, the inclusion of other countries, and longitudinal studies provide intriguing pathways for future research. Second, the correlations between the three dimensions of PIES are found. Even though all tests on convergent and discriminant validity were satisfactory, our concern that common method bias may have impacted our findings cannot be fully alleviated. Thus, to avoid these concerns in future studies, better scales, especially for the measurement of the PIES dimensions should be developed, the number of respondent must be increased or other research methods and designs should be used. Third, even though all estimated models reached significance, and the addition of new variables improved model fit (see Table 6), the explained variance of our final model was still relatively low (Adj R2 = 0.271). This indicates that there are possibly other personality dimensions that explain the SME’s LTO. Future research may further explore this avenue, and, for example, investigate the effects of the other motives (i.e., need for power and need for affiliation), personality traits, and the interplay between implicit and explicit motives and traits. Fourth, our study focuses on LTO, as LTO may have positive outcomes on company growth and economic development (WTO, 2016). Though, a single and exclusive focus on long-term objectives may be too much of a good thing. This exclusive focus may cause SMEs to miss golden opportunities that may not be fully in line with the SME’s long-term objectives. Thus, we recommend including both short and long-term orientation in future studies in order to better understand the dynamics between the companies’ time orientations, the characteristics of the entrepreneurs, and the performance of their SMEs. Fifth, our sample is dominated by the art and handicraft sector. Thus, the generalizability of our research may only be possible for similar industries, especially in developing and emerging countries.

Data availability

The dataset used in this research is available upon request via the corresponding author.

References

Ahlstrom, D., & Bruton, G. D. (2010). Rapid Institutional Shifts and the Co-evolution of Entrepreneurial Firms in Transition Economies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 531–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00373.x

Al Omoush, K. S., Al-Qirem, R. M., & Al Hawatmah, Z. M. (2017). The degree of e-business entrepreneurship and long-term sustainability: An institutional perspective. Information Systems and E-Business Management, 16(1), 29–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10257-017-0340-4

Apers, C., Lang, J. W. B., & Derous, E. (2019). Who earns more? Explicit traits, implicit motives and income growth trajectories. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110(November 2018), 214–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.12.004

Assouad, A., & Parboteeah, K. P. (2017). Religion and innovation. A country institutional approach. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 15(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2017.1378589

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64, 359–372.

Atkinson, J. W. (1958). Motives in fantasy, action, and society: A method of assessment and study. Oxford.

Atkinson, J. W., & Litwin, G. H. (1960). Achievement motive and test anxiety conceived as motive to approach success and motive to avoid failure. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 60(1), 52–63.

Baumann, N., Kaschel, R., & Kuhl, J. (2005). Striving for Unwanted Goals Stress Dependent Discrepancies Between Explicit and Implicit Achievement Motives reduce Subjective Well-Being and Increase Psychosomatic Symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(5), 781–799.

Bearden, W. O., Money, B., & Nevins, J. L. (2006). A Measure of Long-Term Orientation: Development and Validation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(3), 456–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070306286706

Bender, M., & Woike, B. A. (2010). Learning and Memory Correlates of Implicit Motives. In O. C. Schultheiss & J. C. Brunstein (Eds.), Implicit Motives (pp. 211–244). Oxford University Press.

Bernecker, K., & Job, V. (2010). Assessing implicit motives with an online version of the picture story exercise. Motivation and Emotion, 35(3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-010-9175-8

Bing, M. N., LeBreton, J. M., Davison, H. K., Migetz, D. Z., & James, L. R. (2007). Integrating implicit and explicit social cognitions for enhanced personality assessment: A general framework for choosing measurement and statistical methods. Organizational Research Methods, 10(1), 136–179.

Block, J. H., Thams, A., München, T. U., & Berlin, F. U. (2007). Long-term orientation in family and non-family firms: A bayesian analysis. Humboldt University. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/25231

Bosma, N., Content, J., Sanders, M., & Stam, E. (2018). Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth in Europe. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0012-x

Bowen, H. P., & De Clercq, D. (2008). Institutional context and the allocation of entrepreneurial effort. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(4), 747–768. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgnave.jibs.8400343

BPS. (2018a). Pertumbuhan Ekonomi Indonesia Triwulan IV 2017. In Setianto & P. A. Kurniawan (Eds.), Berita Resmi Statistik. Badan Pusat Statistik. https://www.bps.go.id/pressrelease/2018a/02/05/1519/ekonomi-indonesia-triwulan-iv-2017--tumbuh-5-19-persen.html

BPS. (2018b). Pertumbuhan Ekonomi Jawa Timur 2018b. In K. Agus (Ed.), Berita Resmi Statistik. Badan Pusat Statistik Jawa Timur. https://jatim.bps.go.id/pressrelease/2019/02/06/1056/pertumbuhan-ekonomi-jawa-timur-tahun-2018b.html

Brammer, S., Hoejmose, S., & Marchant, K. (2012). Environmental Management in SMEs in the UK: Practices, Pressures and Perceived Benefits. Business Strategy and the Environment, 21, 423–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.717

Brigham, K. H., Lumpkin, G. T., Payne, G. T., & Zachary, M. A. (2014). Researching Long-Term Orientation: A Validation Study and Recommendations for Future Research. Family Business Review, 27(1), 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486513508980

Brody, N. (1963). N Achievement, test Anxiety, and Subjective Probability of Success in Risk Taking Behavior. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66(5), 413–418.

Brouthers, K. D., Andriessen, F., & Nicolaes, I. (1988). Driving blind: Strategic decision making in small companies. Long Range Planning, 31(1), 130.

Brueckner, J., Bosak, J., & Lang, J. W. B. (2021). Connect vs conquer? CEO gender and implicit motives. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 36(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-01-2019-0061

Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Obloj, K. (2008). Entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Where are we today and where should the research go in the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, January, 1–18.

Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H.-L. (2010). Institutional Theory and Entrepreneurship: Where Are We Now and Where Do We Need to Move in the Future? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x

Bruton, G. D., Duane Ireland, R., & Ketchen, D. J. (2012). Toward a research agenda on the informal economy. Academy of Management Perspectives, 26(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0079

Busenitz, L. W., & Lau, C. (1996). A cross-cultural cognitive model of new venture creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879602000403

Busenitz, L. W., Gomez, C., & Spencer, J. W. (2000). Country institutional profiles: Unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 994–1003.

Bylund, P. L., & McCaffrey, M. (2017). A theory of entrepreneurship and institutional uncertainty. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(5), 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.05.006

Cambra-Fierro, J. J., & Polo-Redondo, Y. (2008). Long-term orientation of the supply function in the SME context. International Small Business Journal, 26(5), 619–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242608094032]

Cavusgil, S. T., & Naor, J. (1987). Firm and management characteristics as discriminators of export marketing activity. Journal of Business Research, 15(3), 221–235.

Chang, S. J., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2010). From the editors: Common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(2), 178–184. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27752488

Chen, S., Su, X., & Wu, S. (2012). Need for achievement, education, and entrepreneurial risk-taking behavior. Social Behavior and Personality, 40(8), 1311.

Child, J., Hsieh, L. H. Y., Elbanna, S., Karmowska, J., Marinova, S., Puthusserry, P., Tsai, T., Narooz, R., & Zhang, Y. (2017). SME international business models: The role of context and experience. Journal of World Business, 52(5), 664–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2017.05.004

Chiles, T. H., Bluedorn, A. C., & Gupta, V. K. (2016). Beyond Creative Destruction and Entrepreneurial Discovery: A Radical Austrian Approach to Entrepreneurship. Organization Studies, 28(4), 467–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840606067996

Collins, C. J., Locke, E. A., & Hanges, P. J. (2000). The relationship of need for achievement to entrepreneurial behavior: A meta-analysis. University of Maryland.

Collins, C. J., Hanges, P. J., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of achievement motivation to entrepreneurial behavior: a meta-analysis. Human Performance, 17, 95–117.

Cooper, W. H. (1983). An achievement motivation nomological network. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(4), 841–861.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms In hostile and benign environment. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75.

de Charms, R., Carpenter, V., Klausmeirer, H. J., & O’Hearn, G. T. (1968). Measuring motivation in culturally disadvantaged children. In Research and development toward the improvement of education. WI: Educational Research Services

Dehghanpour Farashah, A. (2015). The effects of demographic, cognitive and institutional factors on development of entrepreneurial intention: Toward a socio-cognitive model of entrepreneurial career. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 13(4), 452–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-015-0144-x

Doh, J. P., Howton, S. D., Howton, S. W., & Siegel, D. S. (2009). Does the Market Respond to an Endorsement of Social Responsibility? The Role of Institutions, Information, and Legitimacy. Journal of Management, 36(6), 1461–1485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309337896

Duncan, L. E., & Peterson, B. E. (2010). Gender and Motivation for Achievement, Affiliation–Intimacy, and Power. In J. C. Chrisler & D. R. McCreary (Eds.), Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology (pp. 41–62). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1467-5_31.

Engel, G., Olson, K. R., & Patrick, C. (2002). The personality of love: Fundamental motives and traits related to components of love. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 839–853.

Evans, L. (2019). Samsung’s Organizational Culture & Its Characteristics (An Analysis). Panmore Institute. http://panmore.com/samsung-organizational-culture-corporate-cultural-characteristics-analysis

Falkner, E. M., & Hiebl, M. R. W. (2015). Risk management in SMEs: A systematic review of available evidence. The Journal of Risk Finance, 16(2), 122–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/jrf-06-2014-0079

Fitzsimons, G. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2010). Interpersonal Influences on Self-Regulation. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(2), 101–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721410364499

Fitzsimons, G. M., & Shah, J. (2008). How goal instrumentality shapes relationship evaluations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 319–337.

Flammer, C. (2013). Corporate Social Responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Academy of Management Journal, 56(3), 758–781.

Flammer, C., & Bansal, P. (2017). Does a long-term orientation create value?. Evidence from a regression discontinuity. Strategic Management Journal, 38, 1827–1847. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj

Francioni, B., Musso, F., & Cioppi, M. (2015). Decision-maker characteristics and international decisions for SMEs. Management Decision, 53(10), 2226–2249. https://doi.org/10.1108/md-03-2015-0094

Gao, C., Zuzul, T., Jones, G., & Khanna, T. (2017). Overcoming Institutional Voids: A Reputation-Based View of Long-Run Survival. Strategic Management Journal, 38(11), 2147–2167. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2649

García-Cabrera, A. M., García-Soto, M. G., & Durán-Herrera, J. J. (2016). Opportunity motivation and SME internationalisation in emerging countries: Evidence from entrepreneurs’ perception of institutions. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(3), 879–910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0386-7

GEM. (2018). Indonesia Entrepreneurial Framework Condition. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. http://gemconsortium.org/economy-profiles/indonesia

GEM. (2021). 2020/2021 Global Report. In Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-20202021-global-report

Gentry, R., Dibrell, C., & Kim, J. (2016). Long-term orientation in publicly traded family businesses: Evidence of a dominant logic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(4), 733–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12140

Gielnik, M. M., & Frese, M. (2013). Entrepreneurship and poverty reduction: Applying I-O psychology to microbusiness and entrepreneurship in developing countries. In J. B. Olson-Buchanan, L. K. Bryan, & L. F. Thompson (Eds.), Using I-O psychology for the greater good: Helping those who help others (pp. 394–438). Routledge, Taylor Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203069264

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Nunez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J. L., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106–137.

Gupta, V. K., Guo, C., Canever, M., Yim, H. R., Sraw, G. K., & Liu, M. (2014). Institutional environment for entrepreneurship in rapidly emerging major economies: The case of Brazil, China, India, and Korea. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(2), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-012-0221-8

Habbershon, T. G., & Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 7(1), 1–26.

Hair, J. F. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. Prentice Hall.

Handrito, R. P., Slabbinck, H., & Vanderstraeten, J. (2020). Enjoying or refraining from risk? The impact of implicit need for achievement and risk perception on SME internationalization. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 27(3), 317–342. https://doi.org/10.1108/ccsm-03-2019-0068

Hansemark, O. C. (2003). Need for achievement, locus of control and the prediction of business start-ups: A longitudinal study. Journal of Economic Psychology, 24(3), 301–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-4870(02)00188-5

Hermans, J., Slabbinck, H., Vanderstraeten, J., Brassey, J., Dejardin, M., Ramdani, D., & van Witteloostuijn, A. (2017). The power paradox: Implicit and explicit power motives, and the importance attached to pro-social organizational goals in SMEs. Sustainability, 9(11), 2001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112001

Heyns, R., Veroff, J., & Atkinson, J. W. (1958). Motives in fantasy, action, and society. In Motives in fantasy, action, and society (pp. 205–218).

Hitt, M. A. (2016). International strategy and institutional environments. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 23(2), 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1108/ccsm-11-2015-0168

Hofer, J., Busch, H., & Kiessling, F. (2008). Individual Pathways to Life Satisfaction: The Significance of Traits and Motives. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(4), 503–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-007-9086-x

Hoffmann, C., Wulf, T., & Stubner, S. (2014). Understanding the performance consequences of family involvement in the top management team: The role of long-term orientation. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 34(3), 345–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242614550500

Hofstede, G. (1980). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do american theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, Summer.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Hsu, W.-T., Chen, H.-L., & Cheng, C.-Y. (2013). Internationalization and firm performance of SMEs: The moderating effects of CEO attributes. Journal of World Business, 48(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2012.06.001