Abstract

This study examines whether and how the experience of poverty shapes the entrepreneurial journey. The research builds upon disadvantage theory to explore how liabilities resulting from the poverty experience can serve as obstacles to the creation of sustainable enterprises. An analysis of data from a sample of 202 entrepreneurs in poverty contexts in the USA demonstrates how liability of poorness (LOP) factors leads to the emergence of more fragile ventures. The findings further indicate that entrepreneurial alertness can moderate the effect of LOP on venture fragility. The study offers theoretical and practical suggestions for further understanding and fostering entrepreneurship as a viable solution to poverty.

Plain English Summary

How poverty conditions affect a person’s ability to start a successful business. Creating a successful business can be difficult for anyone, but especially for those who come from poverty circumstances. This study demonstrates how ventures created by poverty entrepreneurs tend to be more fragile or subject to serious decline or failure when the inevitable threat or unexpected setback occurs. Two key aspects of poverty, experienced scarcity and significant nonbusiness distractions, combine to lead entrepreneurs to create more fragile businesses. However, when a low-income individual demonstrates more entrepreneurial alertness, a variable associated with venture success, the negative effect of poverty-related variables is reduced. The findings suggest that, for entrepreneurship to be a viable pathway out of poverty, public policies and community-based programs should focus on reducing the fragility of these ventures and enhancing the opportunity recognition skills of these entrepreneurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

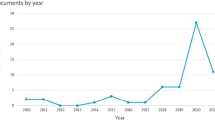

To what extent does entrepreneurship represent a solution to poverty? Recent studies suggest the poor start large numbers of businesses and many are able to improve their economic standing through venture creation (Amorós et al., 2021; Naminse & Zhuang, 2018; Slivinski, 2012). At the same time, a number of observers question the value of such ventures. They argue businesses started by the poor are generally inefficient, fail at high rates, generate few jobs and little intellectual property, and do not contribute to economic productivity (Acs & Kallas, 2008; Acs & Szerb, 2007; Shane, 2009). Morris et al. (2018) explained that those in poverty disproportionately create necessity-driven ventures that suffer from the “commodity trap,” referring to ventures that are undifferentiated and labor-intensive and have low profit margins, high unit costs, no bargaining power, and limited production capacity. As a result, they can be highly fragile businesses, especially vulnerable to shocks and setbacks such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Odeku, 2020).

Such divergent views persist despite the growing volume of scholarship addressing the poverty and entrepreneurship interface (Alvarez & Barney, 2014; Banerjee & Duflo, 2011; Bruton et al., 2013; Castellanza, 2020; Webb et al., 2013). Researchers have produced insufficient empirical evidence to address some of the most formative questions at the interface, such as the rate of start-up activity by those in poverty, failure rates and average life of these ventures, factors contributing to their success, and extent to which these ventures move people out of poverty. Poverty is a multidimensional phenomenon transcending a lack of money (Morland et al., 2002; Wilson, 1996). As such, Morris et al. (2022) concluded that low-income individuals face unique challenges when launching a venture, which they label the “liability of poorness.” The question becomes one of determining how poverty conditions influence the viability of these ventures.

The current research seeks to explore this question. We draw upon disadvantage theory (Light, 1979) to explain how the liability of poorness (LOP) increases the fragility of the businesses being created. Fragility, in this context, refers to “the venture’s vulnerability to inherent obstacles and unexpected shocks and its limited capacity to cope with adverse conditions” (Morris, 2020, p. 304). We approach the LOP in terms of two widely noted challenges faced by low-income individuals: experienced scarcity, or the effects of prolonged exposure to insufficient resources to address basic needs (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013), and an inability to maintain focus, which results from significant nonbusiness distractions (Dermott & Pomati, 2016; Morris et al., 2022).

At the same time, individuals in poverty contexts are not inherently destined to create fragile ventures. Numerous examples exist of entrepreneurs who overcame the disadvantages imposed by poverty to build successful businesses (Bandiera et al., 2013; John & Poisner, 2016). In this regard, researchers have placed significant emphasis on the importance of entrepreneurial alertness, or the ability to detect signals from the environment and recognize business opportunities, as a factor contributing to successful venture creation (Kirzner, 1999). Accordingly, we posit that individuals in poverty contexts can develop cognitive and behavioral capabilities required for expanding the range of opportunities available to them (Alvarez & Barney, 2014), which can enable those individuals to build more viable businesses. Hence, we propose that entrepreneurial alertness can moderate the effect of the LOP on venture fragility.

We develop a research model and set of hypotheses regarding these relationships. To test the hypotheses, a survey was administered to a sample of entrepreneurs from poverty and disadvantaged backgrounds in urban areas within the USA. The results support our hypotheses that poverty conditions can result in higher levels of venture fragility and that entrepreneurial alertness can alleviate the negative effects of the LOP on fragility. Hence, entrepreneurial alertness may be considered as a capability that enables poverty entrepreneurs to leverage entrepreneurship as a pathway out of poverty. Implications are drawn for theory, practice, and policy.

The research offers several contributions. First, the study sheds light on the entrepreneurial journeys of those in poverty and places overcoming fragility at the center of discussions of the efficacy of entrepreneurship as a poverty solution. Fragility has heretofore largely been examined in the context of large, established firms (e.g., Cómbita Mora, 2020; Cueva et al., 2017; Den Haan et al., 2003), with only limited examination of its role in early-stage ventures (Bartik, et al., 2020; Bottazzi, Secchi & Tamagni, 2006; Madi, 2013). Beyond understanding why, how, and the extent to which those experiencing poverty start ventures, a focus on fragility highlights the importance of examining the sustainability of these ventures. Second, our findings contribute to disadvantage theory (Boyd, 2000; Light, 1979) by showing how disadvantages associated with poverty can simultaneously direct individuals towards entrepreneurship while also leading them into potentially problematic ventures that cannot provide a pathway out of poverty. While these contrasting effects are suggested by the duality of disadvantage theory, extant research has emphasized the tendency of the disadvantaged to create informal sector and survival ventures (Boyd, 2000; Herring, 2004; Webb et al., 2013) without considering the sustainability of these ventures. Furthermore, we shed light on how understanding the nature of such disadvantages can provide direction for generating more sustainable ventures. Third, the study adds to the entrepreneurial alertness literature (Amato et al., 2017; Gaglio & Katz, 2001). Alertness has been associated with the number and quality of opportunities identified by entrepreneurs, their tendency to launch ventures, as well as the innovativeness and performance of these ventures (van Gelderin, 2008; Shane et al., 1991; Tang, 2012). This is the first work to highlight its critical role in overcoming disadvantages that derive from the poverty experience. Given that alertness can be taught and improved, the results suggest individuals affected by scarcity can develop capabilities that empower them to create sustainable ventures. These findings have important implications for entrepreneurship policy and education.

1 Research background

While a number of scholars have theorized about issues at the poverty and entrepreneurship interface (e.g., Bruton et al., 2015; Nakara et al., 2021; Neumeyer et al., 2021), most have not positioned their approach within an established theoretical framework. An exception is Santos et al. (2019), who used empowerment theory to explain how entrepreneurship can foster motivation to overcome a sense of powerlessness, a lack of resources, and limited autonomy and ultimately can help individuals gain control over their lives. Similarly, Shepherd et al. (2021) have used the status-attainment theory to understand how entrepreneurs living in Indian slums could derive a sense of worth from entrepreneurship and how their poverty experience compelled greater education for their children. Thus, prior studies have highlighted the importance of poverty entrepreneurship while also recognizing that poverty circumstances put the poor at a disadvantage in the entrepreneurial context (Bruton et al., 2021). As such, a theory of disadvantage is valuable for understanding the poverty and entrepreneurship interface.

Disadvantage theory from sociology (Boyd, 2000; Light, 1979) holds some promise in this regard, particularly in its focus on disadvantage resulting from poverty, economic exclusion, and discrimination. The theory emphasizes the duality of disadvantage when it comes to behavior, where disadvantage serves as motivator and inhibitor. On the one hand, disadvantage can provide a motivation for an individual to pursue entrepreneurship as he or she is less competitive for attractive job opportunities in the mainstream economy. This has been referred to as labor market disadvantage, and it leads individuals to strike out on their own. While the term injunctification has been used to capture a tendency to accept the status quo when in disadvantaged circumstances (Kay et al., 2009), researchers have noted a motivation tied to disadvantage that enables the person to transcend their circumstances, escape the status quo, and realize the fruits of their labors (Krishna, 2004; Williams et al., 2017). Individuals are unwilling to become victims of their circumstances, and, in some instances, their motives are altruistic, wanting something better for their families and the next generation (Rockinson-Szapkiw et al., 2016). Hence, disadvantage can induce a drive for success (John & Poisner 2016; Morris & Tucker, 2021).

When it comes to entrepreneurship, disadvantage as motivator suggests that the downsides of poverty can serve to enhance the relative attractiveness of venture creation, particularly where disadvantage results in less attractive options such as unemployment, significant underemployment, or jobs with subpar wages (Morris et al., 2022). Furthermore, a person in disadvantaged circumstances has a greater tendency to pursue risk-assumptive behavior, such as venture creation, particularly when perceiving they have little to lose (Sadler, 2000; Walton, 2018). In addition, as the individual makes progress in pursuing a venture, they are motivated to persevere in building on those results to ultimately find a pathway out of their disadvantaged circumstances (Krishna, 2004). At the same time, there is some evidence that, when the disadvantaged start ventures, the venture can become an end in itself, where the entrepreneur is motivated by the desire to be his/her own boss, and profit-making is less of a consideration (Wong, 1977; Silverman, 1999).

On the other hand, disadvantage can serve as an inhibitor when it produces constraints or barriers, particularly where it limits the ability and/or willingness of the individual to act. At least four disadvantage-related constraints have been identified: inadequate resources, insufficient capabilities, limits on access to a given opportunity, and diminished self-perceptions of one’s potential and place in society. Poverty conditions often produce all four of these constraints (Morris, et al., 2022; Payne et al., 2006; Wilson, 2012). Furthermore, when the person in poverty is part of a minority or ethnic group, entrepreneurship researchers have found evidence of opportunity-limiting discrimination from a range of different stakeholders (Jackson et al., 2018; Kuppuswamy & Younkin, 2020; Younkin & Kuppuswamy, 2019).

Such constraints can deter the poverty entrepreneur from launching businesses altogether, but, when a venture is pursued, can influence what actually gets created. Constraints can result in a greater tendency to launch survival ventures (Boyd, 2000) and businesses in the informal sector (Herring, 2004; Webb et al., 2013). They can result in entrepreneurs taking what Butler (1991) refers to as an “economic detour,” where they limit the potential of the business by focusing only on their immediate networks and people with similar backgrounds to their own, and fail to penetrate mainstream markets. They believe capital constraints and discrimination close opportunities to them in the broader economy (Silverman, 1999).

Disadvantage theory has been used to explain the entrepreneurial activity of women, immigrants, and minorities (Boyd, 2000; Cooper & Dunkelberg, 1987; Horton & DeJong, 1991; Light & Rosenstein, 1995). Light (1979) relied on this theory to explain increased entrepreneurial activity resulting from overurbanization as rural residents in developing countries move to cities and cannot find work.

In sum, disadvantaged circumstances can push the individual toward entrepreneurship while posing major challenges when developing their ventures. This duality may have important implications for the sustainability of the ventures created by the poor, a topic that has received little attention. The constraints imposed by a poverty background may lead the entrepreneur to approach the business in ways that produce more fragile and underperforming ventures. To appreciate this possibility, we need to first explore the disadvantages created by poverty when launching a venture and then clarify the concept of venture fragility.

1.1 Disadvantage, poverty, and entrepreneurship

Poverty is a key indicator of social exclusion and an underlying characteristic of many of the groups examined in disadvantage studies (e.g., Boyd, 2000; Butler, 1991; Herring, 2004). The disadvantages associated with poverty go well beyond severe financial constraints (Wilson, 1996). Other aspects of the experience that contribute to disadvantage include substandard literacy levels and school drop-out rates well above the norm (Hernandez, 2011), lack of employment opportunities and underemployment in labor-intensive and often part-time jobs with no benefits (Morris et al., 2018), inadequate housing conditions and undernutrition (Morland, et al., 2002), food insecurity (Piaseu & Mitchell, 2004), chronic medical conditions and early child mortality (Von Braun et al., 2009), teenage child-bearing and single parenthood (Maldonado & Nieuwenhuis, 2015), lack of dependable transportation (Chetty & Hendren, 2018), constant fatigue (Tirado, 2015), physical insecurity (Chronic Poverty Research Centre 2009), segregation from much of society (Wilson, 1996), and limited social networks (Weyers et al., 2008).

Morris (2020) has attempted to draw implications from the multidimensional nature of poverty for entrepreneurial activity. All entrepreneurs confront numerous obstacles as reflected in the liabilities of newness and smallness (Hannan & Freeman, 1984; Stinchcombe, 1965). However, the poverty experience can introduce an additional set of obstacles, which has been termed the liabilities of poorness. It refers to “the potential for failure of a new venture due to difficulties encountered that are traceable to the characteristics and influences deriving from a poverty background” (Morris, 2020, p. 311).

Poverty at its essence is a condition of scarcity. Daily choices must be made regarding which bills to pay and things that one must go without. The day-to-day struggle to survive and having to address immediate needs can result in the entrepreneur bringing a scarcity mindset to the venture creation process. Experienced scarcity has been associated with suboptimal decision-making and a short-term orientation (Mani et al, 2013; Shah et al., 2015). In addition, poverty can impose a number of disruptive demands that limit one’s ability to focus on building a business (Castellanza, 2020; Wilson, 2012). Examples can include the threat of eviction from one’s residence, gang violence, unexpected loss of a job, a chronic illness afflicting an uninsured family member, or a child’s school suspension or arbitrary arrest, among other everyday developments. The combination of a scarcity mindset and ongoing distractions can compromise the abilities to plan ahead, think strategically, and prepare for contingencies. Such conditions can represent a significant liability when attempting to navigate the complex demands and unanticipated developments encountered when developing a business.

1.2 LOP and venture fragility

Poverty conditions can have critical implications for the kinds of ventures created by those in poverty. Smith-Hunter and Boyd (2004) have suggested that labor market disadvantage coupled with resource disadvantage explains a tendency for the poor to create survivalist or marginal types of enterprises. Morris et al. (2018) argued that poverty conditions lead the poor to launch ventures that fall into the “commodity trap.” These are undifferentiated businesses that compete on price, are labor-intensive with high unit costs, and have limited capacity and small margins. They lack technology and key production equipment and have limited bargaining power with suppliers and customers. In short, disadvantages are likely to make the ventures of the poor more vulnerable and fragile, particularly following faulty business decisions or when encountering shocks and adverse circumstances (Van Ginneken, 2005). Fragility suggests the firm is less able to withstand these developments and more likely to be severely damaged or fail.

The limited literature on organizational fragility centers on the financial structures of large, established firms that find themselves unable to effectively respond to economic crises. Researchers have explored how external threats make firms with risky balance sheets and few liquid assets more subject to financial collapse (Cueva et al., 2017; Den Haan et al., 2003). Fragility indicates that adverse circumstances can render the organization unable to perform its functions and meet the demands of stakeholders (Cómbita Mora, 2020; Wiklund et al., 2010).

Among the few fragility studies involving small firms, Bottazzi et al. (2006) found the very smallest Italian businesses to be more fragile than firms in general. Madi (2013) explored how the relative fragility of micro and small enterprises in Brazil limited their ability to take advantage of the recovery following a global economic crisis. Bartik et al. (2020) demonstrated how the COVID-19 pandemic revealed higher than expected levels of small business fragility.

As a dispositional property, we need to better understand the role of fragility in businesses created by those in poverty and the extent to which poverty circumstances contribute to this fragility. This brings us to the current research.

1.3 Model and hypotheses

How do the disadvantages conveyed by poverty influence the manner in which venture creation is approached and the fragility of the ventures created? To address this question, we propose the research model presented in Fig. 1. Here, LOP is captured by two elements that have received considerable attention in the poverty literature, experienced scarcity and a compromised ability to focus (Banerjee & Mullainathan, 2008; Bryan et al., 2017; Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013). Its impact on venture fragility is moderated by entrepreneurial alertness, or the individual’s ability, regardless of their resource endowment, to better recognize opportunities.

Experienced scarcity can lead an individual to adopt a short-term orientation (Mani, et al, 2013). Shah et al., (2012, p. 682) argued that “scarcity creates its own mindset, changing how people look at problems and make decisions.” Immediate problems consume a disproportionate amount of the individual’s time, effort, and financial resources. Planning, anticipating, and preparing for future developments and needs and adopting a more strategic orientation become quite difficult (Banerjee & Mullainathan, 2008; Bryan et al., 2017; Wilson, 1996, 2012). In a venture context, the entrepreneur becomes more reactive or tactical in orientation, simply trying to address pressing operational needs. This sort of reactive, short-term perspective can make it difficult to think more holistically about where the business is going, set resources aside for contingencies, and build the sorts of sustained relationships that will enable the business to respond to threats and navigate through difficult times. A preoccupation with immediate problems can also mean the entrepreneur is not developing the knowledge and capabilities associated with key roles that must be filled within the enterprise, particularly roles unrelated to the problems at hand (Baum, 1996; George, 2005). Without sufficient planning, the firm cannot achieve economies in procurement and production. Such planning is also critical for the development of effective routines and procedures over time (Gong et al., 2004). As a result, the business is less prepared for adverse developments and its long-term sustainability is at risk.

A scarcity mindset is coupled with the difficulties the entrepreneur has in focusing on the business. The poverty experience can introduce a range of distractions into the daily lives of entrepreneurs (Bryan et al., 2017; Morris, 2020). It becomes difficult to concentrate on the venture and dedicate the amount of time required if one is coping with medical emergencies, food shortages, threat of eviction from one’s home, shutoff of utilities, or criminal violence, among other nonbusiness demands. While the liability of newness suggests significant learning must take place as the entrepreneur assumes the numerous roles that come into play when building a business (Baum, 1996), these nonbusiness distractions undermine the ability to learn. Lack of complete focus on the enterprise is also likely to produce operational inefficiencies, less planning, and reduced bargaining power with stakeholders. Activities associated with key roles in the business may not receive attention, while the ability to formalize and adhere to key routines can be compromised. The legitimacy of the business can suffer as stakeholders question the entrepreneur’s dedication (Fisher et al., 2017). The result is a more fragile venture. Fragility in this context suggests that the LOP has made the venture more vulnerable to adverse internal or external developments and is unable to adequately respond when they occur. As a result, the venture becomes less able to perform key functions (Cómbita Mora, 2020; Wiklund et al., 2010). The entrepreneur struggles to afford inventory, pay expenses, meet payroll demands, serve customer needs, retain employees, maintain marketing efforts, or sustain relationships with external stakeholders (Morris et al., 2022). Faced with any sort of external threat, the absence of resource slack can force the entrepreneur to reduce capacity, sell assets, or otherwise undermine the ability to create value. The firm becomes more constrained, less competitive, and less economically viable (Madi, 2013). Based on this discussion, we hypothesize:

H1: The entrepreneur’s LOP, as reflected in experienced scarcity and nonbusiness distractions, increases their venture’s fragility, such that higher levels of LOP are associated with a more fragile venture.

Entrepreneurial alertness (EA) refers to the cognitions and behaviors that enable an individual to recognize opportunities (Gaglio & Katz, 2001). It involves the ability to scan and search for information, connect disparate pieces of information, and make evaluations regarding the existence of profitable business opportunities (Tang et al., 2012). Researchers have identified a range of situational (e.g., quality of social networks) and personal (e.g., experience, values, and traits) factors that can influence alertness (Pirhadi et al., 2021; Sharma, 2019). EA has been shown to be instrumental in achieving entrepreneurial outcomes in various contexts (Amato et al., 2017). Where the entrepreneur demonstrates greater alertness, opportunities for starting a venture and addressing setbacks as it develops are more readily recognized.

The poverty experience can constrain an individual’s opportunity horizon (Alvarez & Barney, 2014; Morris et al., 2018). According to Berkman (2015), poverty restricts a person’s vision of what might be possible. It limits the information content to which one is exposed and imposes rules and norms regarding how things are done and how one gets ahead (Welter, 2011). However, aspects of the poverty experience might actually stimulate the individual’s alertness to opportunities (Light & Rosenstein, 1995). Examples include the ongoing need for creative solutions on how to feed or clothe one’s family when there is no money or the resiliency that results from confronting ongoing setbacks. Hence, while we might expect the poverty context to dampen one’s alertness (Chavoushi et al., 2021; Dana, 2007), differences in the relative levels of EA among those in poverty could have important implications. We posit that, when these levels are higher, EA can help reduce the negative impacts of the LOP when developing a venture.

EA can enable individuals in poverty to recognize more promising opportunities. It enables them to develop behavioral patterns (e.g., asking questions, following the news, and searching for information) and cognitive abilities (e.g., connecting the dots, seeing environmental trends, and identifying patterns) through practice and social learning and leverage them to overcome challenges resulting from the LOP. For example, there is evidence suggesting that alertness serves as a vehicle for approaching problem-solving from a more strategic (Roundy et al., 2018), anticipatory (Neneh, 2019; Obschonka et al., 2017), and forward-looking (Tang et al., 2012) perspective, each of which could offset the short-term orientation resulting from scarcity and the reactiveness that results from nonbusiness distractions. This discussion produces the following hypothesis:

H2: The positive effect of the entrepreneur’s LOP on their venture’s fragility is negatively moderated by EA, such that higher levels of EA reduce the positive influence of the LOP on venture fragility.

2 Research methodology

2.1 Data and sample

A cross-sectional survey methodology was employed to test the research model. A self-report questionnaire was designed and administered to early-stage entrepreneurs who come from a poverty background. Access to the desired sample was facilitated by collaboration with a national program that seeks to empower low-income entrepreneurs in urban areas. This program leverages community resources in a number of cities to provide individuals who are often underserved by local entrepreneurial ecosystems with education, mentoring, and related support to help them start and develop businesses. We reached out to the population of 460 participants in this program in four cities during a 4-month period in early 2021. The cities were selected to reflect different geographic regions (the South, West, East, and Midwest) of the United States. Given reported problems in generating responses from low-income and disadvantaged subjects (Jackson & Ivanoff, 1998; Jang & Vorderstrasse, 2019), an incentive in the form of a $15 gift card was offered for participation. From this total, 226 individuals responded to the questionnaire, representing a response rate of 49%. After eliminating 24 surveys due to incompleteness, 202 surveys were used in the analysis.

Within the final sample, 75% of responding entrepreneurs were female, a proportion similar to the overall makeup of the multicity program (see Table 2). The average age of respondents was 41 years. The number of family members living with the entrepreneur ranged from zero to eight (average of 2.7). The average venture age was 3.64 years.

3 Measures

3.1 Dependent variable

Conventional financial ratios and related measures from financial statements employed in fragility studies (e.g., Bruneau et al., 2012; Tuzcuoğlu, 2020) tend not to be available for the ventures of the poor. As a result, we relied upon subjective indicators of fragility, similar to but more extensive than those utilized by Bartik et al. (2020). We consider three major characteristics from the literature that determine the extent to which a business is fragile (Bruneau et al., 2012; Cómbita Mora, 2020; Stonebraker et al., 2007). First, we measured a venture’s “ability to handle expenses” as a proxy for the business liquidity by asking four binary questions. Specifically, we asked the participants to determine, based on the amount of money in their business bank account, whether they could cover a $500 increase in operating expenses, including business rent; pay for a $1000 piece of important equipment; take advantage of a key market opportunity for their business that would require spending $5000; and purchase a used vehicle for the business that costs $10,000. The responses to these four questions were summed to determine the business’s ability to spend cash and cover expenses. Second, we measured the business’s “ability to generate profit” by asking participants approximately how much profit they earned each month over the past 6 months. The entrepreneurs could choose from five options: “none, we have just been breaking even or losing money in some months,” “a small monthly profit, under $1,000 per month,” “a moderate monthly profit, under $5,000 per month,” “a pretty good profit, under $10,000 per month,” or “we have done well, making more than $10,000 in profit per month.” Finally, we measured the business’s “ability to raise external funding” by asking participants, “if you needed to raise money for your business today, which of the following best describes your situation?” Entrepreneurs could choose from four options: “at present it would be very hard for me to qualify for a bank loan,” “I could probably qualify for a small bank loan (under $10,000),” “I could probably qualify for a bank loan of up to $50,000,” or “I could probably qualify for a bank loan of up to $100,000 or more.” These three measures were standardized and averaged to form an overall measure of “venture fragility,” where a higher score indicates a more fragile business.

3.2 Independent variable

LOP is a reflective construct that captures a multifaceted phenomenon (Morris, 2020; Roux et al., 2015; Shah et al., 2015). We focused on two major dimensions of LOP that represent unique aspects of living in poverty, namely, “experienced scarcity” and “nonbusiness distractions.” Bryan et al. (2017) argued that these represent two of the most well-documented psychological phenomena observed among those living in poverty circumstances. To measure experienced scarcity, we developed a set of 11 items that capture how scarcity is related to the ability to address basic needs (Chakravarty & D’Ambrosio, 2006; DeSousa et al., 2020). Sample items include “I have not sought the health/medical care I needed because I could not afford it” and “I sometimes have gone hungry because I could not afford to buy more food.” To measure nonbusiness distractions, six items were employed that reflect critical life demands when experiencing poverty (Mark et al., 2018; Reinholdt-Dunne et al., 2013). Examples include “I am often distracted by outside demands that make it hard to shift my attention back to the business” and “there are issues in my life which take my attention away from my business.” All items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (“1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree”).

3.3 Moderating variable

A commonly used scale developed by Tang et al. (2012) was adopted to measure EA. The scale measures three dimensions of EA: scanning and search, association and connection, and evaluation and judgment. All items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (“1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree”).

3.4 Control variables

Personal and business-related control variables were included in the analysis. At the individual level, the effects of participant’s age, gender, and family size were accounted for, as they have been shown to impact an individual’s ability to run a business (e.g., Gielnik et al., 2017; Rosa et al., 1996a, 1996b). In addition, the effects of venture age and venture size were controlled for. Younger and smaller ventures are inherently more fragile because they are subject to the liabilities of newness and smallness (Aldrich & Auster, 1986). We included two measures of venture size—the numbers of full-time and part-time employees—because these two employee categories have differing implications for a business (Soto‐Simeone et al., 2020).

4 Analysis and results

4.1 Measurement model

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to explore the data structure. Higher than recommended thresholds of the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy (KMO > 0.5) and significance of Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.001) suggested the data is suitable for factor analysis (Thompson, 2004). With the EFA, items with higher-than-0.5 factor loadings on the first principal component were chosen for each of the constructs (three items for venture fragility, six items for each component of LOP, and all items of EA). Then, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using the main latent constructs and their observed items to finalize our measures. Given the sample size and number of constructs, the measurement model was optimized by eliminating items with relatively lower factor loadings to ensure convergence of the structural equation model. This scale purification technique for multi-item measures is a common practice (Wieland et al., 2017). Table 1 presents the final set of items, standard factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and Cronbach’s alphas for each construct. Significant and higher-than-0.4 factor loadings for all items suggest satisfactory convergent validity. In addition, the AVE for each construct was above 0.4 and higher than its common variance with any other construct, which indicates the discriminant validity thresholds were satisfied (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The alphas for all constructs were also above 0.7, suggesting appropriate measure reliability. Moreover, the common fit indices for the CFA model (chi-square/degree of freedom = 1.62, CFI = 0.93, NNFI = 0.92, AGFI = 0.83, RMSEA = 0.05, and SRMR = 0.06) indicate acceptable fit between the measurement model and the data (Hooper et al., 2008). Overall, these results suggest valid and reliable measures that can be used for hypothesis testing.

4.2 Common method variance test

Common method bias (CMB) tends to reduce the estimation of interaction effects (i.e., interaction effects are not artifacts of CMB). Hence, CMB is generally not a major concern in studies, such as the current one, that investigate interactions (Siemsen et al., 2010). Still, Harman’s single factor test was adopted to examine CMB issues. An EFA was performed using all measures while restricting the number of extracted factors to one. CMB can be a major concern if EFA results show that a significant part of the variance (> 50%) in the data is explained by a single factor (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Results indicated that less than 16% of the variance could be explained by one factor, suggesting no major CMB concerns.

4.3 Hypotheses testing

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables can be found in Table 2. Positive and significant correlations between both firm age and size and venture fragility suggest that, as expected, older and larger businesses are less fragile compared to younger and smaller ones. We standardized all variables and used hierarchical linear regression analysis for hypothesis testing.

The analysis includes regression models built along three hierarchical steps. The base model includes all control variables. The main-effect model is formed by adding the main variables (i.e., LOP and EA) to the base model, and the contingency model includes an additional term for the interaction between LOP and EA. Regression assumptions were checked using common diagnostics and the significance of the R2 change was examined using the F test. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) were less than the suggested thresholds (VIFs < 1.17), indicating no multicollinearity issue with the models (Hair et al., 1998).

Table 3 presents the results for the hierarchical regression analysis. The base model (R2 = 0.144, p < 0.001) explained 14.4% of the variance in venture fragility. As expected, the regression results suggest that venture age has a marginally significant and negative influence on fragility (β = − 0.12, p < 0.1), meaning that older firms tend to be less fragile. Regarding venture size, the results indicated no significant relationship between number of full-time employees and fragility (β = − 0.07, p > 0.1), but they did indicate a significant negative link between number of part-time employees and fragility (β = − 0.18, p < 0.05). These results are potentially important as they suggest employing part-time employees might be a more effective strategy for improving venture fragility, compared to full-time employees, as it provides greater flexibility and cost efficiency. Further, the relationship between gender and fragility is significant and positive (β = 0.26, p < 0.001), suggesting ventures run by women are more fragile.

The main-effect model (R2 = 0.205, p < 0.001) can explain the 6.1% additional variance in venture fragility (ΔR2 = 0.061, < 0.01). The model indicates that LOP has a significant and positive relationship with venture fragility (β = 0.24, p < 0.01). This result provides strong support for H1. In addition, the contingency model (R2 = 0.221, p < 0.001) can explain the 1.6% additional variability in venture fragility (ΔR2 = 0.016, p < 0.05). The interaction between LOP and EA has a significant and negative relationship with venture fragility (β = − 0.13, p < 0.05). This indicates that EA can weaken the positive influence of LOP on venture fragility, providing strong support for H2.

We further examined this interaction effect by drawing graphs for the effect of LOP on venture fragility for low, medium, and high (− 1, 0, and + 1 standard deviation) levels of EA. As illustrated in Fig. 2, higher levels of LOP lead to the emergence of more fragile businesses and the slope of line is steeper when EA is lower, which suggests a stronger positive effect of LOP on venture fragility. Table 4 provides the conditional effects of LOP on venture fragility at low, medium, and high values of EA (Hayes, 2017). As shown in Table 4, LOP has a stronger positive effect on venture fragility when EA is low (β = 0.3979, p = 0.0001) compared to when EA is medium (β = 0.2724, p = 0.0001) or high ((β = 0.1469, p = 0.0631). As another robustness test, we performed a slope difference test suggested by Dawson (2014) to examine whether the effect of LOP on venture fragility is significantly higher than zero for low and high levels of EA and found consistent results that show the effect is stronger and significant when EA is low (β = 0.40, p = 0.0001), and weaker and non-significant when EA is high (β = 0.15, p = 0.10). In fact, the nonsignificant slope difference test for high levels of EA may suggest that the destructive effects of LOP on venture fragility can be totally avoided if the entrepreneur can develop high levels of EA. In sum, ventures run by entrepreneurs who experience similar levels of LOP may suffer from varying levels of fragility depending on their EA; the more entrepreneurially alert entrepreneurs are, the less their ventures are fragile because of their LOP.

5 Discussion

Poverty continues to have a pervasive impact on people’s lives across the globe (World Bank, 2021), with entrepreneurship proposed as a potential solution (Amorós et al., 2021; Sutter et al., 2019). This study has sought to examine how situational characteristics of poverty, as reflected in the LOP, influence ventures created by the poor. Where much of the empirical work on poverty and entrepreneurship has focused on developing economies, we focused on a developed economy context, where poverty rates have not meaningfully declined over 50 years. Using disadvantage theory, we generated a sample of entrepreneurs from poverty backgrounds to examine how the experience of scarcity and the nonbusiness distractions resulting from poverty conditions influence venture fragility. The results aligned with our research model and hypotheses. Both of these LOP factors lead entrepreneurs to create ventures that are more fragile. We further probe this relationship by examining a moderating effect. The results suggest higher levels of EA can lessen the impact of LOP on fragility. Thus, EA appears to compensate for the deleterious impact of poverty conditions on how the entrepreneur approaches venture creation.

This study highlights the importance of a focus on venture fragility for advancing knowledge at the poverty and entrepreneurship interface. Research on small business fragility is quite limited. Based on the liabilities of newness and smallness (Hannan & Freeman, 1984; Stinchcombe, 1965), it can be argued that early-stage ventures are inherently fragile, at least more so than larger, better-established firms. Yet we find variability in fragility across our sample, suggesting there may be actions entrepreneurs can take which affect relative fragility, even in severely resource-constrained contexts. The abilities to set aside time for planning, not compromise future prospects by focusing purely on immediate needs, approach decision-making from a more holistic and strategic vantage point, and maintain focus in the face of significant nonbusiness demands would appear critical for developing a more resilient enterprise.

The importance of fragility as an outcome warranting study is that it represents an ongoing state that reflects the extent to which the business is in serious trouble when the inevitable threat or unexpected development materializes. Other performance measures at a given point in time may not accurately reflect how precarious the business is. Significant revenue and profit declines following some disruptive event can be symptomatic of a business that is inherently more fragile, and it is this fragility that requires attention if the organization is to become more sustainable from a sales or profit vantage point. Fragility suggests the business cannot respond adequately to setbacks or disruptions and is unlikely to be sustainable.

In addition, our findings advance disadvantage theory by showing how liabilities associated with poverty can directly extend to the venture creation process and can compromise the ability of these ventures to provide a pathway out of poverty. Prior scholarship has suggested that disadvantages associated with poverty can induce poor decision-making, resulting in sustained poverty and circumstances that keep individuals from pursuing entrepreneurship (Bryan et al., 2017; Sheehy-Skeffington & Rea, 2017). The current research goes a step further to demonstrate that when entrepreneurship is pursued, the result can be more fragile ventures, suggesting that more attention be placed on the situational constraints of poverty and their impacts across the venture development process.

As a possible extension of disadvantage theory, we see the dual aspect of disadvantage at work; furthermore, we see that these dual forces are operating simultaneously and against one another. Disadvantage both drives and inhibits the individual, where the net effect is the creation of something new, but something that is marginalized in terms of constrained potential. Disadvantage creates a kind of dialectic, where the drive to rise above poverty is in opposition to the way one thinks and one’s ability to focus. While our emphasis has been on disadvantage, poverty also can produce certain assets, such as the motivation to escape poverty, resiliency from dealing with setbacks, and creativity in finding ways to survive and support a family (Light & Rosenstein, 1995; Morris & Tucker, 2021; Wilson, 2012). In a sense, poverty assets are in conflict with poverty liabilities.

This brings us to alertness. There were entrepreneurs in our sample with higher levels of EA, where alertness contributed to making ventures less fragile. For its part, EA represents an individual-level capability that does not directly address disadvantage-induced fragility; instead, it interacts with the effects of poverty in ways that serve to counter the liability and perhaps accentuate the assets. While we did not measure the latter possibility, this is an important question for future research. It appears that the inhibiting aspects of disadvantage can push the individual into entrepreneurship (sometimes but not always out of necessity), often producing more marginal businesses, while the motivating aspects of disadvantage can pull the individual toward opportunity and creation of more sustainable ventures. As such, the linkage between disadvantage and opportunity recognition warrants further investigation (Alvarez & Barney, 2014; Baron & Ensley, 2006).

Our findings add to the literature on EA (Tang et al., 2012), suggesting that alertness can be leveraged as a resource among poverty entrepreneurs, allowing them to expand the range of possibilities for their ventures. This implies that, while poverty might be a situational phenomenon, there are individual-level factors that can offset the disadvantages associated with poverty. The challenge is to develop richer insights into how the depth and breadth of the opportunity horizons of those in poverty contexts can be expanded. Furthermore, new insights are needed into how to nurture among the disadvantaged the cognitive abilities and behavioral patterns required for EA (Hajizadeh & Zali, 2016; Ozgen & Baron, 2007). Empowering these individuals to expand their opportunity horizons and see more possibilities in their lives can complement public efforts to remove institutional barriers that cause social exclusion and discrimination, thereby helping to develop a more equal and inclusive society.

Our findings regarding gender are also noteworthy. The fact that women entrepreneurs in our sample created more fragile businesses is consistent with previous findings. Different studies have found that female-owned firms were more likely than those owned by males to close, and had lower levels of sales, profits, and employment (Kalleberg & Leicht, 1991; Robb & Wolken, 2002; Robb, 2002; Rosa et al., 1996a, 1996b). While these performance differences have been attributed to race, education and training, work experience, access to capital, and type of industry (see Fairlie & Robb, 2008 for a comprehensive review), poverty represents an additional explanation. Hence, the disadvantages confronted by women in general would appear to be exacerbated by poverty conditions, consistent with our arguments about the liabilities of poorness. As the literature stresses the emphasis by women entrepreneurs on balance between work demands and family (e.g., Agarwal & Lenka, 2015; Coleman, 2016), the difficulties in focusing on the business due to family-related distractions (e.g., effects on family members of chronic illness, food scarcity, gang influences, physical insecurity, and so forth) might be especially important in this regard.

Turning to implications for practice, the poor begin at a disadvantage when they launch ventures. This disadvantage is exacerbated by the lack of infrastructure in poorer communities and the failure of entrepreneurial ecosystems to adequately support those in poverty (Neumeyer et al., 2019; Weyers et al., 2008). Part of the challenge here is the need to tailor assistance and support to reflect the LOP and its implications for the creation of sustainable enterprises.

Experienced scarcity represents a case in point. If exposed to a prolonged period of scarcity, where one is preoccupied with short-term family survival, tradeoffs must regularly be made in what expenses are paid, and immediate exigencies take precedence over consideration for the longer-term implications of decisions. Forced to confront a host of novel issues in an unfamiliar context (i.e., a start-up venture), the entrepreneur struggles to take the kinds of actions that will produce a sustainable enterprise. It is not enough to tell the entrepreneur how important it is to plan or engage in strategic thinking. Assistance is needed in setting priorities, knowing what can and cannot be sacrificed in the short term, recognizing the interdependencies among decisions in different areas of a business, and understanding intermediate and longer-term costs of trade-off decisions. Training, mentoring, and other forms of support can also help the entrepreneur appreciate the kinds of short-term actions that can lessen venture fragility.

Similar implications can be drawn regarding nonbusiness distractions. The single mother who is working two part-time jobs while attempting to develop a business struggles to find the time to creatively leverage resources, develop novel marketing methods, or try a new production approach. She is not only the prime source of labor in what is typically a labor-intensive business, but is distracted by a host of poverty-related circumstances This represents a scenario where more enlightened public policies combined with local ecosystems that are more poverty-inclusive can play a significant role. Whether through subsidized childcare, income subsidies tied to venture progress, vouchers to cover the costs of part-time employees through the first two years of a venture, mentor–protégé programs connecting the entrepreneur to established businesses in the industry, or other creative approaches, the ability of the low-income entrepreneur to focus on venture priorities can be enhanced in ways that support sustainability.

5.1 Limitations and future research directions

These findings must be interpreted with the limitations of the study in mind. Among these is the subjective nature of the measures employed. We asked respondents to self-report their levels of experienced scarcity and nonbusiness distractions and relied on subjective indicators of venture fragility. Regarding fragility, while we attempted to rectify this concern by developing items based on prior literature, an objective measure of venture fragility might better serve the ability to capture the effects of poverty on venture outcomes.

Poverty is a complex phenomenon experienced uniquely by individuals. While all study participants came from a poverty background, we did not ascertain the extent of their poverty circumstances. Our measure of the LOP can potentially serve as a proxy indicator, but future studies might explore how various dimensions of poverty (e.g., housing stability, food security, and chronic health problems) affect those being studied. A related limitation is the lack of entrepreneurs in the sample who are not experiencing poverty. Hence, while we compared the fragility of businesses created by those who suffer varying levels of the LOP, we could not compare how fragility differs between entrepreneurs who do and do not come from poverty backgrounds. In particular, as most start-ups are arguably to some degree fragile, such a comparison would reinforce the relationship between poverty and fragility.

Finally, the cross-sectional nature of our study prevents us from understanding how the effects of poverty influence venture performance over time. Because we asked about ventures at one point in time, we lack insights into the temporal relationship between poverty and venture development. This issue is important for several reasons. First, it is unclear how (e.g., through learning during the venture development process) entrepreneurs may be able to outgrow the effects of poverty, or whether these effects remain pernicious throughout a venture’s life. Second, we assumed that less fragile ventures could provide a pathway out of poverty without being able to capture how reductions in venture fragility contribute over time to the entrepreneur’s well-being. Similarly, our research method does not allow us to infer whether and how venture fragility might actually worsen poverty conditions over time.

Based on the results, a number of important avenues for future research can be identified. Our findings suggest a need to further investigate factors that can improve or exacerbate venture fragility. Examples include characteristics of the entrepreneur (e.g., literacy and skills) and business-related factors (e.g., resourcing strategies). The results also suggest that females tend to create more fragile ventures, but richer insights are needed into possible institutional, venture-related, personal or situational factors that could help explain this gender gap.

While we explored the impact of EA, scholars might further examine the opportunity horizons of those in poverty. The issue may not simply be how alert one is to opportunities, but their alertness to higher potential opportunities. An associated question concerns how the pursuit of entrepreneurship affects opportunity horizons. The ability to escape the commodity trap and build a sustainable enterprise is tied to adaptation and acting upon new opportunities as they emerge (Morris et al., 2012; Ronstadt, 1988). To what extent does the venture experience itself change or improve the opportunities the entrepreneur is able to perceive?

Lastly, researchers might further explore the implications of fragility. Does it lead to more conservatism in decision-making, missed opportunities, and less adaptation, such that fragility results in behaviors that contribute to even greater fragility? Does it limit the socioeconomic mobility of the entrepreneur, such that addressing venture fragility becomes the key to entrepreneurship as a viable pathway out of poverty? These possibilities suggest a need for parallel investigations into both venture outcomes and family outcomes and, with the latter, research that explores multigenerational effects.

References

Acs, Z. J. & Kallas, K. (2008). State of literature on small- to medium-sized enterprises and entrepreneurship in low-income communities. In: Yago, G., Barth, J. R., & Zeidman, B. (eds.). Entrepreneurship in emerging domestic markets. Springer–Milken Institute. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-72857-5_3

Acs, Z. J., & Szerb, L. (2007). Entrepreneurship, economic growth and public policy. Small Business Economics, 28(2–3), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9012-3

Agarwal, S., & Lenka, U. (2015). Study on work-life balance of women entrepreneurs – review and research agenda. Industrial and Commercial Training, 47(7), 356–362. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-01-2015-0006

Aldrich, H. A., & Auster, E. (1986). Even dwarf started small: Liabilities of size and age and their strategic implications. In B. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior, 8 (pp. 165–198). JAI Press.

Alvarez, S. A., & Barney, J. B. (2014). Entrepreneurial opportunities and poverty alleviation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(1), 159–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12078

Amato, C., Baron, R. A., Barbieri, B., Belanger, J. J., & Pierro, A. (2017). Regulatory modes and entrepreneurship: The mediational role of alertness in small business success. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(sup1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12255

Amorós, J. E., Ramírez, L. M., Rodríguez-Aceves, L., & Ruiz, l. E. (2021). Revisiting poverty and entrepreneurship in developing countries. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 2150008. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946721500084

Bandiera, O., Burgess, R., Das, N., Gulesci, S., Rasul, I., & Sulaiman, M. (2013). Can basic entrepreneurship transform the economic lives of the poor? https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2266813

Banerjee, A.V., & Duflo, E. (2011). Poor economics: a radical rethinking of the way to fight global poverty. Public Affairs.

Banerjee, A. V., & Mullainathan, S. (2008). Limited attention and income distribution. American Economic Review, 98(2), 489–493. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.2.489

Baron, R. A., & Ensley, M. D. (2006). Opportunity recognition as the detection of meaningful patterns: Evidence from comparisons of novice and experienced entrepreneurs. Management Science, 52(9), 1331–1344. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0538

Bartik, A. W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(30), 17656–17666. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2006991117

Baum, J. A. C. (1996). Organizational ecology. In S. Clegg, C. Hardy, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational Studies (pp. 77–114). Sage.

Berkman, E. (2015). Poor people don’t have less self-control. Poverty forces them to think short-term. New Republic (September 22). Retrieved from https://newrepublic.com/article/122887/poor-people-don’t-have-less-self-control

Bottazzi, G., Secchi, A., Tamagni, F. (2006). Financial fragility and growth dynamics of Italian business firms (No. 2006/07). LEM Working Paper Series. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/89394

Boyd, R. (2000). Survivalist entrepreneurship among urban blacks during the Great Depression: a test of the disadvantage theory of business enterprise. Social Science Quarterly, 972–984. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42864032

Bruneau, C., de Bandt, O., & El Amri, W. (2012). Macroeconomic fluctuations and corporate financial fragility. Journal of Financial Stability, 8(4), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2012.02.002

Bruton, G. D., Ketchen, D. J., & Ireland, R. D. (2013). Entrepreneurship as a solution to poverty. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(6), 683–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.05.002

Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Si, S. (2015). Entrepreneurship, poverty, and Asia: moving beyond subsistence entrepreneurship. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-014-9404-x

Bruton, G., Sutter, C., & Lenz, A. K. (2021). Economic inequality—is entrepreneurship the cause or the solution? A review and research agenda for emerging economies. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(3), 106095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106095

Butler, J. S. (1991). Entrepreneurship and self-help among black Americans. State University of New York Press.

Bryan, C. J., Mazar, N., Jamison, J., Braithwaite, J., Dechausay, N., Fishbane, A., Fox, E., Gauri, V., Glennerster, R., Haushofer, J., & Vakis, R. (2017). Overcoming behavioral obstacles to escaping poverty. Behavioral Science & Policy, 3(1), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1353/bsp.2017.0007

Castellanza, L. (2020). Discipline, abjection, and poverty alleviation through entrepreneurship: a constitutive perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 106032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106032

Chakravarty, S. R., & D’Ambrosio, C. (2006). The measurement of social exclusion. Review of Income and Wealth, 52(3), 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.2006.00195.x

Chavoushi, Z. H., Zali, M. R., Valliere, D., Faghih, N., Hejazi, R., & Dehkordi, A. M. (2021). Entrepreneurial alertness: A systematic literature review. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 33(2), 123–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2012.01419.x

Chetty, R., & Hendren, N. (2018). The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility II: County-level estimates. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(3), 1163–1228. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy006

Chronic Poverty Research Centre. (2009). The chronic poverty report 2008–09: escaping poverty traps. Chronic Poverty Research Centre.

Coleman, S. (2016). Gender, entrepreneurship, and firm performance: Recent research and considerations of context. In M. L. Connerley & J. Wu (Eds.), Handbook on Well-Being of Working Women (pp. 375–391). Springer Science.

Cómbita Mora, G. (2020). Structural change and financial fragility in the Colombian business sector: a post Keynesian approach. Cuadernos de Economía, 39(80), 567–594. https://doi.org/10.15446/cuad.econ.v39n80.82562

Cooper, A.C., & Dunkelberg, W. (1987) Entrepreneurial research: old questions, new answers and methodological issues. American Journal of Small Business (Winter), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225878701100301

Cueva, D., Cortes, S, Tapia, R, Tabi, w., Torres, J, Maza, C., Uyaguari, K., & Gonzalez, M (2017). Financial fragility of companies—estimation of a probabilistic model LOGIT and PROBIT: Ecuadorian case. 12th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Lisbon, 2017, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.23919/CISTI.2017.7975927

Dana, L. P. (2007). Handbook of research on ethnic minority entrepreneurship: a co-evolutionary view on resource management. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781847209962

Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

Den Haan, W. J., Ramey, G., & Watson, J. (2003). Liquidity flows and fragility of business enterprises. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(6), 1215–1241. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(03)00077-1

Dermott, E., & Pomati, M. (2016). ‘Good’ parenting practices: How important are poverty, education and time pressure? Sociology, 50(1), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038514560260

DeSousa, M., Reeve, C. L., & Peterman, A. H. (2020). Development and initial validation of the Perceived Scarcity Scale. Stress and Health, 36(2), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2908

Fairlie, R. & Robb, A. (2008). Gender differences in business performance: evidence from the characteristics of business owners survey. IZA Discussion Paper 3718, Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor. https://repec.iza.org/dp3718.pdf.

Fisher, G., Kuratko, D. F., Bloodgood, J., & Hornsby, J. S. (2017). Legitimate to whom? Audience diversity and individual level new venture legitimacy judgments. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(1), 52–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.10.005

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Gaglio, C. M., & Katz, J. A. (2001). The psychological basis of opportunity identification: Entrepreneurial alertness. Small Business Economics, 16(2), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011132102464

George, G. (2005). Slack resources and the performance of privately held firms. Academy of Management Journal, 48(4), 661–676. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.17843944

Gielnik, M. M., Zacher, H., & Schmitt, A. (2017). How small business managers’ age and focus on opportunities affect business growth: A mediated moderation growth model. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(3), 460–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12253

Gong, Y., Baker, T., & Miner, A. S., (2004). Where do routines come from in new ventures? Proceedings, Academy of Management Annual Meetings, New Orleans, LA.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tathum, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis with readings. Macmillan.

Hajizadeh, A., & Zali, M. (2016). Prior knowledge, cognitive characteristics and opportunity recognition. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-05-2015-0110

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1984). Structural inertia and organizational change. American Sociology Review, 49, 149–164. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095567

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

Hernandez, D. J. (2011). Double jeopardy: how third grade reading skills and poverty influence high school graduation. ERIC, April, Baltimore, MD Annie E: Casey Foundation.

Herring, C. (2004). Open for business in the black metropolis: Race, disadvantage, and entrepreneurial activity in Chicago’s inner city. The Review of Black Political Economy, 31(4), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12114-004-1009-z

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Evaluating model fit: a synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature. In: 7th European conference on research methodology for business and management studies,195–200.

Horton, H., & De Jong, G. (1991). Black entrepreneurs: A socio-demographic analysis. Research in Race and Ethnic Relations, 6, 105–120.

Jackson, A. P., & Ivanoff, A. (1998). Reduction of low response rates in interview surveys of poor African-American families. Journal of Social Service Research, 25(1–2), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1300/J079v25n01_03

Jackson, W., Marino, L., Naidoo, J., & Tucker, R. (2018). Size matters: impact of loan size on measures of disparate treatment toward minority entrepreneurs in the small firm credit market. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 8, 4. https://doi.org/10.1515/erj-2018-0129

Jang, M., & Vorderstrasse, A. (2019). Socioeconomic status and racial or ethnic differences in participation: Web-based survey. JMIR Research Protocols, 8(4), e11865. https://doi.org/10.2196/11865

John, D., & Poisner D. (2016). The power of broke. Currency Publishing.

Kalleberg, A., & Leicht, K. (1991). Gender and organizational performance: Determinants of small business survival and success. Academy of Management Journal, 34(1), 136–161. https://doi.org/10.5465/256305

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., Peach, J. M., Laurin, K., Friesen, J., Zanna, M. P., & Spencer, S. J. (2009). Inequality, discrimination, and the power of the status quo. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(3), 421. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015997

Kirzner, I. M. (1999). Creativity and/or alertness: A reconsideration of the Schumpeterian entrepreneur. The Review of Austrian Economics, 11(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007719905868

Krishna, A. (2004). Escaping poverty and becoming poor: Who gains, who loses, and why? World Development, 32(1), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.08.002

Kuppuswamy, V., & Younkin, P. (2020). Testing the theory of consumer discrimination as an explanation for the lack of minority hiring in Hollywood films. Management Science, 66(3), 1227–1247. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2018.3241

Light, I. (1979). Disadvantaged minorities in self-employment. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 20(1–2), 31–45.

Light, I. H., & Rosenstein, C. N. (1995). Race, ethnicity, and entrepreneurship in urban America. Transaction Publishers.

Madi, M. A. C. (2013). Micro and small business in Brazil: Asymmetries and financial fragility. International Journal of Globalisation and Small Business, 5(3), 136–147.

Maldonado, L. C., & Nieuwenhuis, R. (2015). Family policies and single parent poverty in 18 OECD countries, 1978–2008. Community, Work & Family, 18(4), 395–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2015.1080661

Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., & Zhao, J. (2013). Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science, 341(6149), 976–980. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1238041

Mark, G., Czerwinski, M., & Iqbal, S.T. (2018). Effects of individual differences in blocking workplace distractions. Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: 1–12. New York: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173666

Morland, K., Wing, S., Diez Roux, A., & Poole, C. (2002). Neighborhood characteristics associated with location of food stores and food service places. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 22(1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00403-2

Morris, M. H. (2020). The liability of poorness: Why the playing field is not level for poverty entrepreneurs. Poverty and Public Policy, 12(3), 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/pop4.283

Morris, M. H., Kuratko, D. F., Schindehutte, M., & Spivack, A. J. (2012). Framing the entrepreneurial experience. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 11–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00471.x

Morris, M. H., Santos, S. C., & Neumeyer, X. (2018). Poverty and entrepreneurship in developed economies. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Morris, M.H., & Tucker, R. (2021). The entrepreneurial mindset and poverty. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1890096

Morris, M. H., Kuratko, D. F., Audretsch, D. B., & Santos, S. (2022). Overcoming the liability of poorness: Disadvantage, fragility and the poverty entrepreneur. Small Business Economics, 58(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00409-w

Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. Macmillan.

Nakara, W. A., Messeghem, K., & Ramaroson, A. (2021). Innovation and entrepreneurship in a context of poverty: A multilevel approach. Small Business Economics, 56, 1601–1617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00281-3

Naminse, E. Y., & Zhuang, J. (2018). Does farmer entrepreneurship alleviate rural poverty in China? Evidence from Guangxi Province. PLOS One, 13(3), e0194912. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194912

Neneh, B. N. (2019). From entrepreneurial alertness to entrepreneurial behavior: The role of trait competitiveness and proactive personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.10.020

Neumeyer, X., Santos, S. C., & Morris, M. H. (2019). Who is left out: Exploring social boundaries in entrepreneurial ecosystems. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(2), 462–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9694-0

Neumeyer, X., Santos, S. C., & Morris, M. H. (2021). Overcoming barriers to technology adoption when fostering entrepreneurship among the poor: The role of technology and digital literacy. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 68(6), 1605–1618. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2020.2989740

Obschonka, M., Hakkarainen, K., Lonka, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2017). Entrepreneurship as a twenty-first century skill: Entrepreneurial alertness and intention in the transition to adulthood. Small Business Economics, 48(3), 487–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9798-6

Odeku, K. O. (2020). The plight of women entrepreneurs during covid-19 pandemic lockdown in South Africa. Gender & Behaviour, 18(3), 16068–16074.

Ozgen, E., & Baron, R. A. (2007). Social sources of information in opportunity recognition: Effects of mentors, industry networks, and professional forums. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(2), 174–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.12.001

Piaseu, N., & Mitchell, P. (2004). Household food insecurity among urban poor in Thailand. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04023.x

Payne, R. K., DeVol, P., & Smith, T. D. (2006). Bridges out of poverty. Process Inc.

Pirhadi, H., Soleimanof, S., & Feyzbakhsh, A. (2021). Unpacking entrepreneurial alertness: how character matters for entrepreneurial thinking. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1907584

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Reinholdt-Dunne, M. L., Mogg, K., & Bradley, B. P. (2013). Attention control: Relationships between self-report and behavioural measures, and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Cognition & Emotion, 27(3), 430–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2012.715081

Rosa, P., Carter, S., & Hamilton, D. (1996a). Gender as a determinant of small business performance: Insights from a British study. Small Business Economics, 8, 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00390031

Robb, A. (2002). Entrepreneurship: A path for economic advancement for women and minorities? Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 7(4), 383–397.

Robb, A. & Wolken, J. (2002) Firm, owner, and financing characteristics: differences between female- and male-owned small businesses, Federal Reserve Working Paper Series: 2002–18. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=306800

Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. J., Spaulding, L., & Spaulding, M. (2016). Identifying significant integration and institutional factors that predict online doctoral persistence. The Internet and Higher Education, 31, 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2016.07.003

Ronstadt, R. (1988). The corridor principle. Journal of Business Venturing, 3(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(88)90028-6

Rosa, P., Carter, S., & Hamilton, D. (1996b). Gender as a determinant of small business performance: Insights from a British study. Small Business Economics, 8(6), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00390031

Roundy, P. T., Harrison, D. A., Khavul, S., Pérez-Nordtvedt, L., & McGee, J. E. (2018). Entrepreneurial alertness as a pathway to strategic decisions and organizational performance. Strategic Organization, 16(2), 192–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127017693970

Roux, C., Goldsmith, K., & Bonezzi, A. (2015). On the psychology of scarcity: When reminders of resource scarcity promote selfish (and generous) behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(4), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucv048

Sadler, M. A. (2000). Escaping poverty: Risk-taking and endogenous inequality in a model of equilibrium growth. Review of Economic Dynamics, 3(4), 704–725. https://doi.org/10.1006/redy.1999.0088

Santos, S. C., Neumeyer, X., & Morris, M. H. (2019). Entrepreneurship education in a poverty context: An empowerment perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 57, 6–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12485

Shah, A. K., Shafir, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2015). Scarcity frames value. Psychological Science, 26(4), 402–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614563958

Shah, A. K., Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2012). Some consequences of having too little. Science, 338(6107), 682–685. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.12224

Shane, S., Kolvereid, L., & Westhead, P. (1991). An exploratory examination of the reasons leading to new firm formation across country and gender. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(6), 431–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(91)90029-D

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9215-5

Sharma, L. (2019). A systematic review of entrepreneurial alertness. Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 11(2), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-05-2018-0049

Shepherd, D. A., Parida, V., & Wincent, J. (2021). Entrepreneurship and poverty alleviation: The importance of health and children’s education for slum entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(2), 350–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719900774

Sheehy-Skeffington, J., & Rea, J. (2017). How poverty affects people’s decision-making processes. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Siemsen, E., Roth, A., & Oliveira, P. (2010). Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 456–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109351241

Silverman, R. M. (1999). Black business, group resources, and the economic detour: Contemporary Black manufacturers in Chicago’s ethnic beauty aids industry. Journal of Black Studies, 30(2), 232–258.

Slivinski, S. (2012). Goldwater Institute policy report: increasing entrepreneurship is a key to lowering poverty rates (No. 254). Report.

Smith-Hunter, A. E., & Boyd, R. L. (2004). Applying theories of entrepreneurship to a comparative analysis of white and minority business owners. Women in Management Review, 19(1/2), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420410518403

Soto-Simeone, A., Sirén, C., & Antretter, T. (2020). New venture survival: A review and extension. International Journal of Management Reviews, 22(4), 378–407.

Stinchcombe, A.L. (1965). Social structure and organizations. In: Handbook of organizations. Rand McNally. 142–193.

Stonebraker, W. P., Goldhar, J., & Nassos, G., (2007). Toward a framework of supply chain sustainability: the fragility index. Proceedings. Production Operation Management Annual Conference (May). 1–27

Sutter, C., Bruton, G. D., & Chen, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(1), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.06.003

Tang, J., Kacmar, K. M. M., & Busenitz, L. (2012). Entrepreneurial alertness in the pursuit of new opportunities. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.07.001

Thompson, B. (2004). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding concepts and applications. American Psychological Association.

Tirado, L. (2015). Hand to mouth: Living in bootstrap America. Penguin.

Tuzcuoğlu, T. (2020). The impact of financial fragility on firm performance: An analysis of BIST companies. Quantitative Finance and Economics, 4(2), 310–342. https://doi.org/10.3934/QFE.2020015

Van Ginneken, W. (2005). Managing risk and minimizing vulnerability: The role of social protection in pro-poor growth. ILO.

Von Braun, J., Vargas Hill, R., & Pandya-Lorch, R. (2009). The poorest and hungry: assessments, analyses and action: an IFPRI 2020 book. International Food Policy Research Institute. https://doi.org/10.2499/9780896296602BK

Walton, A. (2018). How poverty changes your mindset. Chicago Booth Review. Retrieved from http://review.chicagobooth.edu/behavioralscience/2018/article/how-poverty-changes-your-mind-set.