Abstract

The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between acquisitions and mobility of knowledge workers and managers in small technology companies and how individual skills and capabilities moderate this relationship. Relying on the matched employer–employee data of the Swedish high-tech sectors from 2007 to 2015, we find that acquisitions increase the likelihood of employee departures, mainly in the form of switching to another employer, but that these acquisition effects are weaker for employees with technological competences. By contrast, the acquisition effects are found to be weaker for employees with managerial competences only when acquirers have a strong employee retention motive. When acquirers do not have a strong retention motive, managers, compared to other employees, are more likely to exit the (national) labor market after acquisitions. Our results suggest that the retention motive is a critical condition to explain post-acquisition employee turnover. Both technological and managerial competences are the types of human capital valued by acquirers when they have a strong retention motive.

Plain English Summary

Over recent decades, the increasing importance of high-skilled knowledge workers has been reflected in the changing nature of acquisitions. In high-tech sectors, human capital has become a major asset that is valued or even targeted by many acquirers, especially when target firms are small technology ventures. However, extant literature has exclusively focused on the antecedents of post-acquisition turnover of executives in large public companies. How do acquisitions impact on the mobility of knowledge workers and managers in small technology firms? Drawing on the perspective of human capital theory, this study focuses on the role of technological and managerial skills of employees in post-acquisition employee turnover. Based on the matched employer–employee data of the Swedish high-tech sectors from 2007 to 2015, we find the following results. First, acquisitions increase the likelihood of employee departures. Second, the departures are mainly in the form of changing jobs. Third, the acquisition effects are weaker for employees with technological competences. Fourth, the acquisition effects are weaker for employees with managerial competences when acquirers have a strong employee retention motive. When acquirers do not have a strong retention motive, managers, compared to other employees, are more likely to exit the (national) labor market after acquisitions. Our findings show that retention of technological competences, compared to retention of managerial competences, is less dependent on the retention motive. This may suggest that technological capability is a more core source of competitiveness in a small technology firm. An implication of this study is that future research on post-acquisition employee mobility should go beyond management teams and give more attention to knowledge professionals with technological competences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Human resource management is a critical element which matters for post-acquisition integration and performance (Larsson and Finkelstein, 1999). Scholars have emphasized the importance of retention of employees of acquired firms in facilitating post-acquisition knowledge transfer and integration, particularly for acquisitions in knowledge-intensive sectors (Park et al., 2018; Ranft and Lord, 2000). However, acquisitions are usually followed by large-scale employee departures (Krug et al., 2014; Walsh, 1988; Wu and Zang, 2009). Who leaves and who stays? It is essential to advance our understanding of what factors cause and influence employee mobility of acquired firms following an acquisition.

Over recent decades, the increasing importance of high-skilled knowledge workers has been reflected in the changing nature of acquisitions. In high-tech sectors, human capital has become a major asset that is valued or even targeted in many acquisitions, especially when target firms are small technology ventures (Colombo and Grilli, 2005; Ranft and Lord, 2000). The term “acqui-hiring” has recently emerged to describe the phenomenon of gaining access to target employees through acquisitions of small firms. This has become a new trend for many technology companies in Silicon Valley, such as Google and Facebook, to obtain talented engineers (Chatterji and Patro, 2014; Coyle and Polsky, 2013). However, extant literature has exclusively focused on the antecedents of post-acquisition turnover of executives of large public companies (Hambrick and Cannella, 1993; Krug and Hegarty, 1997; Krug et al., 2014; Walsh, 1988). So far, no attention has been paid to how acquisitions influence employees of small technology ventures, especially those knowledge workers who are perceived as the knowledge core of acquired firms (Paruchuri et al., 2006).

To fill this gap, this study seeks to advance the understanding of how acquisitions impact on mobility of knowledge workers and managers in small technology companies. More specifically, we explore whether and when there exist acqui-hiring effects on post-acquisition mobility (i.e., when acquisitions exhibit negative effects on employee departures). Previous theories suggest that acquisitions, as a disruptive event, cause major organizational change and uncertainty, which may lead to new job matching processes between employees and employers. This could be reflected as a higher employee turnover shortly after acquisitions in acquired firms. We posit that if acqui-hiring effects exist, that is, human capital is the major assets valued by acquirers, the new matching/selection processes following acquisitions should be influenced by human capital characteristics. We hypothesize that individual skills and capabilities moderate the relationship between acquisitions and employee departures. We focus on the role of technological and managerial skills of employees of acquired firms, given that they are both argued to constitute the major source of competence of a small technology firm.

The existing literature has emphasized two important factors when explaining what causes the phenomenon of high turnover rates of executives following an acquisition. The first is acquisition motive, which is related to involuntary turnover. Earlier studies focus on the motive of corporate control. This strand of research argues that managerial teams use acquisitions as a mechanism of market discipline to compete for the management of corporate resources (Jensen and Ruback, 1983; Manne, 1965). Managerial teams of acquiring firms are thus expected to replace inefficient managerial teams of acquired firms after acquisitions to realize potential synergy gains (Lowenstein, 1983). The second factor is psychological state, which is related to voluntary turnover. This group of studies turns to the factors related to executives’ psychological attributes or perceptions, such as perceptions of lost job status or autonomy or fears of alienation, which are found to be positively associated with post-acquisition departure of target executives (Hambrick and Cannella, 1993; Krug and Nigh, 2001; Krug et al., 2014). Little is known about the role of human capital in post-acquisition employee mobility. One exception is the study by Buchholtz et al., (2003), which finds that acquiring firms tend to retain the CEOs who are expected to generate higher returns from investment in their human capital. Although this study distinguishes between general and specific human capital, it focuses on the role of human capital accumulation, e.g., using CEO age and tenure as proxies for human capital. To the best knowledge of the authors, there has been no systematic study exploring how post-acquisition turnover of employees is influenced by specializations of individual skills or capabilities.

This study employs matched employer–employee data on the population of Swedish firms to test our hypotheses. We follow knowledge workers and managers of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the Swedish high-tech sectors from 2007 to 2015. We adopt two measures of employee departures. The first measure focuses on total departures, that is, departures without considering how the individuals leave their current jobs. The second measure distinguishes departures by switching to another job from departures by exiting the labor market. We compare the differences in mobility both between acquired firms and non-acquired firms and before and after acquisitions. We observe that individuals show a lower propensity of departure in acquired firms than non-acquired firms before acquisitions. We use an entropy balancing approach (Abadie et al., 2010; Distel et al., 2019) to account for the self-selection bias where less mobile individuals are more likely to choose to work at acquired firms. Using high-dimensional fixed effects models which account for heterogeneity at both individual and firm levels, we find that acquisitions increase the likelihood of employee departures, mainly in the form of switching to another employer, but the acquisition effects are weaker for employees with technological skills. However, the acquisition effects are weaker for employees with managerial skills only when acquirers have a strong employee retention motive. When acquirers do not have a strong retention motive, managers, compared to other employees, are more likely to exit the (national) labor market after acquisitions.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we discuss the theoretical framework and propose the hypotheses. In Section 3, we present the data and methodology. In Section 4, we report the results. Finally, in Section 5 we discuss the implications and conclude the paper.

2 Theoretical framework and hypotheses

2.1 Organizational change and employee turnover

Employee turnover involves both involuntary and voluntary turnover. Involuntary turnover is independent of the control of employees, referring to job cessation caused by external or unexpected events, such as an organization’s management strategies or the death of the employee (Morrell et al., 2001). On the contrary, voluntary turnover refers to job cessation initiated by employees. Voluntary turnover can be explained by a wide range of factors, e.g., job satisfaction, job alternatives, individual traits, psychological status, organizational factors, and job performance (Jackofsky, 1984; Lee and Mitchell, 1994; March and Simon, 1958; Morrell et al., 2001, 2004a; Morrison and Robinson, 1997). Organizational change is a salient factor which is related to both involuntary and voluntary turnover. It often entails a significant transition in organizational structure, culture, or business strategy. In this sense, organizational change may trigger a set of implementation strategies from the management to strive for the intended aims. These initiatives may include downsizing or restructuring programs and could thus lead to large-scale involuntary turnover. Moreover, organizational change brings instability, uncertainty, and possibly feelings of disenchantment (Baron et al., 2001), leading to a “shock” prompting thoughts of job searching or employees’ final decisions to leave voluntarily (Lee and Mitchell, 1994; Morrell et al., 2004a, 2004b).

2.2 Acquisition effects from the perspective of human capital theory

Human capital theory views employee turnover as a result of evaluations of human capital investment (Becker, 1962; Buchholtz et al., 2003). This process is jointly influenced by three sets of factors: individual characteristics, employer (and job) characteristics, and job matching processes between individuals and employers (Fujiwara-Greve and Greve, 2000; Granovetter, 1981; Jovanovic, 1979). Acquisitions involve transactions of ownership rights between legal bodies (Lindholm, 1994). After the ownership change, both new owners and existing employees may reevaluate the expected returns of human capital investment from their own perspectives. This could break the current equilibrium of employee–job matches in target firms.

2.2.1 Acquisition effects on involuntary turnover

From the perspective of employers, new owners may have different insights about which human capital to invest in. All acquisitions are driven by some specific motives. Post-acquisition integration and implementation strategies are directed by the major motives behind acquisitions. For example, mergers and acquisitions in the 1960s or 1970s were mainly driven by the purposes of corporate growth/diversification or financial synergies (Kolev et al., 2012; Matsusaka, 1993). In this case, large-scale layoffs are expected as the outcome of removing redundancy after acquisitions to realize operational synergies (Trautwein, 1990). Over recent decades, acquisitions are more often driven by gaining access to capabilities or even human capital per se (Arora et al., 2001; Chatterji and Patro, 2014; Coyle and Polsky, 2013). In this case, new owners may be more precise about which human capital they value and invest in. Post-acquisition employee turnover can be seen as a process of selecting and integrating human resources by acquirers. No matter which motives an acquirer holds, an acquisition could cause a reshuffle of human resources and lead to a higher involuntary turnover on average.

2.2.2 Acquisition effects on voluntary turnover

From the perspective of employees, acquisitions may trigger shocks and thus alter their evaluation of whether they continue investing in firm-specific human capital in the current organization. Previous studies find that post-acquisition turnover of target executives is much influenced by their perceptions of social status after acquisitions (Hambrick and Cannella, 1993; Krug and Nigh, 2001). After acquisitions, executives in acquired firms may perceive or worry about situations like lost job status/autonomy or alienation, which are found to be positively related to post-acquisition departures (Hambrick and Cannella, 1993; Krug and Nigh, 2001; Krug et al., 2014). Although existing empirical evidence concentrates mainly on post-acquisition mobility of top executives, there is indirect evidence showing that other employees are also influenced by acquisitions. A study by Paruchuri et al. (2006) shows that the productivity of technical personnel, especially those who lost their social status after an acquisition, is much impaired by post-acquisition integration. Hence, the first hypothesis is proposed as follows:

H1: Employees in acquired firms have a higher likelihood of job departures after acquisitions than employees in non-acquired firms.

2.3 Moderating effects of human capital

2.3.1 Moderating effects on involuntary turnover

Human capital contains an individual stock of knowledge, skills, and capabilities which can generate future returns through investment therein (Becker, 1962). Prior studies argue that employees with high-quality human capital, such as high levels of innate ability, better education, or rich working experience, are at an advantage in terms of relative bargaining power, job status, or authority (Campbell et al., 2012; Castanias and Helfat, 2001). One reason is because high-quality human capital constitutes a major component of a firm’s competitive advantage, which is expected to create important value for employers (Barney, 1991; Campbell et al., 2012). It is also because employers may worry about losing high-quality human assets to competitors, which may cause unfavorable knowledge leakage (Wezel et al., 2006). In this sense, acquiring firms may view investment in high-level human capital as a rational decision and thus prefer to retain employees with high-level human capital relative to low-level human capital. However, this prediction is based on the assumption that the human capital is the type valued by the acquirer. If the human capital is not the type valued by the acquirer, the acquirer is less motivated to invest in this type of human capital and thus tends to replace these employees. In this situation, the higher the level of human capital of an employee, the more likely it is that the employee will be replaced because the new owner tends to save the high costs of maintaining these employees.

2.3.2 Moderating effects on voluntary turnover

As pointed out by Ranft and Lord (2000), unlike other types of assets, human assets cannot be purchased or owned outright. Even though new owners may intend to retain some employees, these employees can still choose to leave. The literature reveals that psychological perception of social status is a key mechanism influencing post-acquisition voluntary turnover of target executives (Hambrick and Cannella, 1993; Krug and Nigh, 2001). If an employee possesses the type of human capital valued by the acquirer, the acquirer tends to launch retention programs to promote the retention of this type of employee after acquisition. In this situation, the higher an employee’s level of human capital, the less likely it is that the employee will confront psychological loss induced by the acquisition. One reason could be that the employee with a high level of human capital is the main target of these programs and thus feels more that his/her value is recognized and appreciated by the new owner. Another reason could be that the employee with a high level of human capital has stronger bargaining power relative to the new owner or more external job alternatives and is thus less likely to worry about losing their job status/autonomy or being replaced after acquisition. By contrast, for an employee without the type of human capital valued by the acquirer, he/she is more likely to experience status loss or worry about losing social status after acquisition, which may prompt the decision process of quitting. Especially employees with a high level of human capital could be more sensitive to job satisfaction, because they may value a feeling of accomplishment from work more than employees with a low level of human capital. On the other hand, employees with a high level of human capital may have more external job alternatives, which may motivate them to react more actively to their worry of losing job status or satisfaction (Jackofsky, 1984). In this situation, the higher an employee’s level of human capital, the more likely it is that the employee will confront psychological loss induced by the acquisition.

Thus, how human capital moderates the relationship between acquisitions and employee turnover depends on the condition of whether the human capital is the type valued by the acquirer.

2.3.3 Technological skills and capabilities

Individuals do not only possess divergent levels of knowledge, skills, or capabilities, but also specialize in different subjects. Technological capability has been recognized as one major source of a firm’s competence (Colombo and Grilli, 2005; Ranft and Lord, 2000). According to the knowledge-based view, technological capabilities are argued to be mainly embodied in the complex knowledge of individuals (Grant, 1996; Kogut and Zander, 1992; Ranft and Lord, 2000). For example, learning-by-hiring of scientists or inventors has been highlighted as one critical mechanism for firms to search for technologically distant knowledge (Kaiser et al., 2018; Palomeras and Melero, 2010; Rao and Drazin, 2002; Rosenkopf and Almeida, 2003; Tzabbar, 2009). This makes professionals with technological competences targeted assets for many acquisitions or even the major motive that drives acquisitions (Chatterji and Patro, 2014; Coyle and Polsky, 2013). Moreover, a large amount of evidence in the mobility literature shows that the mobility of technical or R&D (research and development) personnel is a major source of knowledge diffusion or spillovers (Kaiser et al., 2015; Moen, 2005, 2007). This may lead employers to worry about losing professionals with key technological capabilities to competitors and undermining the competences of the firms. Thus, we expect that technological skills and competences are the type of human capital valued by acquiring firms and acquiring firms tend to retain the employees with technological skills after acquisitions.

From the perspective of individuals, employees with the human capital valued by acquirers are expected to be less likely to confront psychological loss induced by the acquisitions. Thus, we expect that employees with technological skills are less likely to leave voluntarily after acquisitions than other employees with a similar level of human capital. We propose our second hypothesis as follows.

H2: Employees in acquired firms have a higher likelihood of job departures after acquisitions, but the effects are weaker for employees with technological skills.

2.3.4 Managerial skills and capabilities

Similarly, managerial capability is another major source of firms’ competence (Castanias and Helfat, 2001). Managers are a group of employees who possess key knowledge of the firm and relational capital with the stakeholders (Krug et al., 2014). When it comes to small ventures, managerial skills and capabilities required for these types of organizations are particularly different from those for large incumbent firms (see, e.g., Krishnan and Scullion, 2017). Studies show that small firms facilitate the development of entrepreneurial human capital, as small firms are important agents for spawning new entrepreneurs (Elfenbein et al., 2010). For acquisitions that are driven by gaining access to technologies and capabilities, acquiring firms need not only technological capabilities, but also the corresponding managerial capabilities and experience to facilitate knowledge integration and to better manage the acquired personnel who are used to the organizational culture of small firms. It is also possible that some firms are searching for managers who could combine entrepreneurial skills and managerial experience to help create entrepreneurial capacity in acquiring firms (Lavie, 2006). As managerial knowledge is usually tacit and requires a long-term experiential learning process to accumulate (Castanias and Helfat, 1991), it is difficult to obtain through education or on-the-job training in an organization which lacks a nurturing environment of entrepreneurship.

On the other hand, acquisitions could also be driven by the motive of corporate control. In such a scenario, efficient managerial teams could use acquisitions as a mechanism of market discipline to replace inefficient managerial teams of acquired firms (Jensen and Ruback, 1983; Lowenstein, 1983; Manne, 1965). Then, acquirers are more likely to replace target managers, on the one hand to save operational costs, on the other hand to eliminate potential resistance from target managers and increase control of acquired firms (Krug et al., 2014).

From the perspective of individuals, managers (especially top executives) may be more likely to confront status or psychological loss after acquisitions and choose to leave voluntarily even if their skills are valued by the new owners because they are used to being the decision-makers of the target firm and have their own images on how to develop and manage the firm (Buchholtz et al., 2003). This may be especially true for the owner-managers who are also the founders of the firms. An owner-manager may value non-pecuniary benefits more, such as autonomy, from his/her work as an entrepreneur (Hamilton, 2000; Hundley, 2001). In this sense, owner-managers may be more likely to leave voluntarily, compared to non-owner-managers who are hired as professional managers with less emotional attachment to the acquired firms.

Being a manager may exert opposite effects on post-acquisition departures. The opposite effects could offset each other, and it is difficult to draw the definite hypotheses concerning the net moderating effects. Thus, we propose a set of competing hypotheses as follows.

H3a: Employees in acquired firms have a higher likelihood of job departures after acquisitions, but the effects are weaker for employees with managerial skills.

H3b: Employees in acquired firms have a higher likelihood of job departures after acquisitions, and the effects are stronger for employees with managerial skills.

H3c: Employees in acquired firms have a higher likelihood of job departures after acquisitions, and the effects are not significantly different for employees with managerial skills.

3 Data and empirical strategy

3.1 Data

We test our hypotheses using the matched employer–employee data compiled by Statistics Sweden (SCB) for the period of 2007–2015. The data from SCB contain anonymized matched employer–employee statistics of the whole population of Swedish firms and working population. We have access to detailed firm and labor market information, such as firm dynamics, firm-level characteristics (e.g., firm size, industry), individual labor market records (e.g., age, gender, education level, education subject, occupation, business owners). We assemble a longitudinal dataset containing variables at both individual and firm levels.

3.1.1 Identifying SMEs in high-tech sectors

In the present study, we define small technology firms as SMEs in high-tech industries in both manufacturingFootnote 1 and knowledge-intensive services. High-tech sectors are identified according to the Eurostat typology (NACE Rev. 2).Footnote 2 Following the definition from the European Commission (2009), we identify SMEs as firms with less than 250 employees. To capture the relatively young firms, we only include the SMEs founded after 1990.

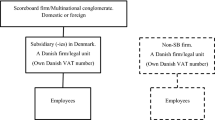

3.1.2 Identifying acquired firms (treatment group) and non-acquired firms (control group)

We identify independent SMEs from 2007 to 2013 and follow them until 2015.Footnote 3 An acquisition is identified when a firm’s ownership is observed to change from being independent to being controlled by an existing business group (Andersson and Xiao, 2016). To avoid acquisitions made for the purpose of share restructuring instead of real changes of owners, we exclude acquisitions when acquirers and targets share the same organizational numbers. We also exclude SMEs with more than one ownership change during the observation period because frequent and multiple ownership changes make it difficult to link acquisition effects to a specific acquisition. To build a control group, we identify non-acquired firms as SMEs which are independent during the whole observation period. In Appendix 4, we show the detailed procedures of how we build the sample of firms.

3.1.3 Linking individuals to firms.

At the individual level, we identify the employees who worked in acquired or non-acquired firms when the firms were observed in the data for the first time. Since the present study focuses on post-acquisition mobility of knowledge workers and managers, we only keep individuals with professional or managerial positions. In Appendix 1, we discuss the details of how we identify knowledge workers and managers.

We follow the individuals over time to identify whether the individual has experienced any change in employer. For individuals in acquired firms, we follow them until the fourth year after acquisitions. The first reason is to remain consistent with previous studies (e.g., Buchholtz et al., 2003; Hambrick and Cannella, 1993), so that we can compare the results with those of previous research. The second reason is because post-acquisition integration and restructuring activities are found to concentrate within 4 years after acquisitions (Xiao, 2018).

The final dataset is organized in a person-year format, containing 87,974 observations. The treatment group contains 13,372 observations and the control group contains 74,602 observations. At firm level, the final dataset contains 831 acquired firms and 14,658 non-acquired firms. About 92% of the firms are in high-tech knowledge-intensive services sectors and the remaining 8% are in high-tech manufacturing sectors. At the individual level, the dataset contains 23,165 individuals.Footnote 4

3.2 Variables

3.2.1 Dependent variables.

We distinguish between three types of employee status: stay, switch, and exit. The reference state is stay, which refers to the situation when an employee remains in the target firm. Switch refers to the situation when an employee switches to a job at another firm. Exit refers to the situation when an individual drops out of the (national) labor market, for example to be unemployed, or to become a student or move outside the country.

3.2.2 Independent and moderating variables

-

Acquisition status

Acquisition status is coded as one at the time of and after target firms experienced ownership changes.

-

Technological/managerial skills

As discussed in Section 2.3, managerial skills much depend on experiential learning processes to accumulate. Managers, especially those in small firms, could have diverse education or subject backgrounds.Footnote 5 We thus use work content with managerial responsibilities as proxy for managerial skills.

Comparatively, educational background is more important for the identification of technological skills. The accumulation of technological skills requires some entry level of technological knowledge and competences, which are usually acquired through formal education. As technology is related to applications of scientific knowledge in practices and industries, we use education background (based on their highest education) in engineering disciplines as proxy for technological skills.

3.2.3 Control variables

We follow the literature and use a set of indicators to proxy the levels of three types of human capital: general, firm-specific, and industry-specific human capital.

-

General human capital

We construct the dummy variable of college to indicate educational level, with one referring to individuals who have education at or above college level (≥ 2 years post-secondary education). The variable of age is used to indicate general work experience of an employee.

-

Firm-specific human capital

The variables of tenure and salary are used to measure individual firm-specific human capital at target firms. We construct tenure by tracing the records of employers from 1990 (the earliest available year for individual data to which we have access), calculating the number of years that the individual worked in the target firm. The variable of salary is annual salary income (in thousands of Swedish Kronor). We deflate salary by using the CPI index with the base year of 2007.

-

Industry-specific human capital

We use industry experience to measure industry-specific human capital. This variable is calculated based on the number of years that the individual worked in the target industry (two-digit NACE level). Because of the frequent updates of industry classification schemes over time, we can only measure this variable consistently until 2010. For individuals who worked in a firm entering after 2010, this variable is missing. We thus only include this variable in the robustness check.

It is quite common that business owners of target firms also work in their own firms. However, the post-acquisition mobility of owners may be influenced by some restrictive agreements, such as non-compete agreements. We thus include a variable of owner to distinguish the individuals who were business owners from the other employees.

We also include the variables of gender and children to control for the impacts of gender and having young children on employee mobility (Albrecht et al., 2018; Valcour & Tolbert, 2003). Children is measured on whether the individual has any children under 18 years old.

The literature on labor economics and industrial organization holds that mobility of workers is a matching and sorting process which is closely associated with firm characteristics and outcomes (see, e.g., Haltiwanger et al., 1999). To account for the potential impacts of determinants at organizational level, we include a set of firm-level/industry-level variables.

-

Industry

To account for the potential differences in employee mobility between manufacturing and service sectors, we distinguish firms in high-tech manufacturing sectors (Manu) from high-tech knowledge-intensive services sectors (the reference group).

-

Firm size

Firm age and size are widely recognized as two fundamental indicators of firm attributes (Evans, 1987; Jovanovic, 1982). Since our sample focuses on young firms (over 90% ≤ 10 years old, over 70% ≤ 5 years old), firm age is highly correlated with individual tenure. Thus, we only include Firm size (measured by number of employees) of target firms to account for its potential impacts on employee mobility.Footnote 6

-

Firm productivity

To account for the different levels of performance between firms, we include the variable of Productivity, defined as value-added per employee. Productivity is deflated by using the CPI index with the base year of 2007. To reduce the potential measurement error, e.g., the existence of unreliable values, we exclude the observations if the values of value added are below the 5th percentile. We only include this variable in the robustness check because of missing values.

In addition, we include year dummy variables to account for potential impacts of the macro-economic situation on employee mobility. Except for dependent variables, acquisition status, and year dummy variables, all the other variables are time-invariantFootnote 7 and measured when firms/individuals were observed in the data for the first time.

3.3 Empirical strategy

As the outcome of our analysis is a binary response, non-linear regressions are usually used for estimations. However, non-linear models, like the logit or probit model, suffer from the problem of interpretability, especially for interaction terms. Studies point out that the moderating effect in a non-linear model is not indicated by the estimated coefficient, sign, or statistical significance of the interaction term (Ai and Norton, 2003; Wiersema and Bowen, 2009). Moreover, since moderating effects in a non-linear model depend on the joint values of all the model variables (Wiersema and Bowen, 2009), it is difficult to summarize and present the effects.

Given this situation, we use linear probability regression as the benchmark model for estimations. In recent years, more scholars have emphasized the merits of using a linear probability model as an alternative for non-linear models on many occasions (Hellevik, 2009; Von Hippel, 2015). Since the main interest of this study is on the moderating effects, the use of a liner model would make the interpretation of results more intuitive. Moreover, Hellevik (2009) shows that the impact of violating the homoscedasticity assumption, which was argued to be one major disadvantage of linear probability model for modeling a binary dependent variable, is quite marginal. In practice, this violation can be solved by calculating heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors.

Since the individual data are collected from multiple years and nested within firms, we include fixed effects at both individual and firm levels to control for heterogeneity at individual and firm levels (high-dimensional fixed effects estimator). The benchmark model of our analysis is displayed in Model (1). To test moderating effects, we extend the model by including the interaction terms between acquisition and moderators (see Model (2)).

\({y}_{ijt}\) refers to the employee status for individual i at firm j in year t, with 1 indicating the individual has left the firm and 0 otherwise; \({acqui}_{jt}\) is the acquisition status for firm j in year t, with 1 indicating that the firm has been acquired; \({tech}_{i}\) refers to individual i with technological skills; \({manager}_{i}\) refers to individual i with managerial skills; \({\theta }_{i}\) is the individual-level fixed effect; \({\mu }_{j}\) is the firm-level fixed effect; \({\rho }_{t}\) is year dummy variables; and \({\varepsilon }_{ijt}\) is the error term.

Since the present study aims to explore acquisition effects on employee mobility, a potential endogeneity may arise if more (or less) mobile individuals are more likely to choose to work in acquired firms. To account for the potential self-selection biases, we use an entropy balancing approach to pre-balance the data based on observed covariates (Abadie et al., 2010; Distel et al., 2019). Like other matching strategies, the rationale of entropy balancing is to make treatment and control group as “similar” as possible so that the treatment can be assumed as a “random” event conditional on observed characteristics. The balancing is achieved by constructing a synthetic control group, which is a weighted average of control observations (Abadie et al., 2010). With this approach, scholars do not need to assume any functional form or intervene in the balancing process (Distel et al., 2019). This is one major advantage that distinguishes the approach from other matching strategies, such as propensity score matching or coarsened exact matching (Bandick and Görg, 2010; Grimpe et al., 2019). In our regression analysis, we employ all the control variables to balance between treatment and control groups. The weights created by entropy balancing are inserted into regressions to account for the potential self-selection biases.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive analysis

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics of the main variables. In terms of dependent variables, about 16% of the individuals have experienced job departures. A total of 12% have switched to a different firm and 4% have dropped out of the (national) labor market. In terms of independent and moderating variables, 9% of the individuals work in acquired firms, 43% of the individuals have a background in engineering fields, and 20% are managers. The average employee in our dataset is about 42 years old and has worked in the firm for 3 years and in the industry for 8 years. The annual salary is about 320,000 SEK (2007 price level) on average. In addition, 56% of the individuals have (at least) college education, 86% are males, and 46% have one or more children under 18 years old. It is interesting to note that 62% of the individuals are also owners of the firms. In terms of firm-level characteristics, around 10% of the individuals work in the (high-tech) manufacturing sectors. The average firm has 8 employees and the value added per employee is about 630,000 SEK (2007 price level). The correlation matrix for independent variables is shown in Table 7 in Appendix 2.

Table 2 displays the switch/exit ratios for three different acquisition status groups: treatment group (before acquisitions), treatment group (after acquisitions), and control group. The upper panel of Table 2 reports the switch/exit ratios of all individuals (knowledge workers and managers) between each group. When we focus on the total switch ratios, it is clear that the treatment group (before acquisitions) has the lowest switch ratio (8.74%), followed by the control group (12.23%) and the treatment group (after acquisitions) (15.10%). The pattern of switch is persistent even if we compare the switch ratios over time. When it comes to the total exit ratios, the treatment group (before acquisitions) still has the lowest exit ratio (2.02%), but the control group has the highest exit ratio (4.37%), followed by the treatment group (after acquisitions) (2.77%). The pattern of exit is also persistent over time, except for in 2012 when the exit ratio is slightly higher for the treatment group (after acquisitions) than the control group. The lower panel of Table 2 reports the total switch/exit ratios of employees with technological and managerial skills between groups, respectively. The patterns of switch or exit between groups are similar to those that emerge when focusing on all individuals. However, compared to all individuals, the increases of ratios of both switch and exit after acquisitions than before acquisitions for the treatment group are lower for employees with technological skills but higher for managers. The results of Table 2 reveal that individuals who work in acquired firms show a lower propensity to switch jobs or exit the labor market before acquisitions; acquisitions tend to increase departure by switching job or exiting the labor market; and the increase of departure ratios seems to be smaller for employees with an engineering background but higher for managers.

We pre-balance the data between treatment and control groups based on the entropy balancing approach. We compare the mean values of covariates between the treatment and control groups before and after balancing, respectively, in Table 8 in Appendix 2.Footnote 8 It is noted that there are no significant differences in mean values of covariates after balancing.

4.2 Regression analysis

In the regression analysis, we adopt two measures of employee departures. The first measure focuses on total departures, regardless of how individuals leave their current jobs. The second measure distinguishes departures by switching to other jobs from departures by exiting the (national) labor market. Table 3 presents the results of acquisition effects on job departures based on Model (1). Before we include entropy balancing weights, acquisitions are found to increase total job departures significantly. Employees in acquired firms are associated with a

7% higher probability to leave their firms after acquisitions. However, when we distinguish the effects between departure routes, we find different effects of acquisitions on switch and exit. Employees in acquired firms are associated with an 8% higher probability to move to a different firm but a 1% lower probability to exit the labor market. After we include entropy balancing weights, the magnitudes of acquisition effects on both total departures and switch decrease. However, the sign of acquisition effects on exit flips to positive but becomes insignificant after controlling for the self-selection effects. The results confirm that, compared to their counterparts in non-acquired firms, employees in acquired firms are indeed more likely to leave their firms after acquisitions. Therefore, H1 is supported. Moreover, the job departures after acquisitions are mainly in the form of switching to another job.

Table 4 presents the results based on Model (2), where the interaction terms are added. The coefficients of interaction terms capture the moderating effects—the impacts of technological or managerial skills on the relationship between acquisitions and job departures. From the panel which does not include entropy balancing weights, it is noted that the coefficients of acqui*tech are all negative and significant, regardless of whether we take account of total departures or whether we distinguish between departure routes. By contrast, the moderating effect of managerial skills is only significant (positive) when the dependent variable is exit. The moderating effects exhibit a similar pattern even after including entropy balancing weights. The results confirm that the acquisition effects on job departures are weaker for employees with technological skills. Therefore, H2 is supported. When we focus on total departures in general, we do not find that the acquisition effects on job departures are significantly different for managers. However, when we distinguish between departure routes, managers, compared to other employees, are found to be more likely to exit the (national) labor market after acquisitions.

Since we only find insignificant moderating effects of managerial skills on total departures and switch, this makes it difficult for us to differentiate the mechanisms of how managerial skills influence acquisition effects on total departures and switch. The insignificant finding may be because managers do not differ from other employees in terms of post-acquisition total departures or switch. It may also be because managerial skills exert opposite moderating effects on total departures or switch, which offset each other and thus cannot be captured by the net moderating effect. To better illuminate the role of managerial skills in total departures and switch, we separate the moderating effects by differentiating the acquisition motives. We construct the variable retention to measure whether acquirers show a strong interest in retaining employees on average after acquisitions. We use the employee retention motive to proxy for the acquisition motive of gaining access to target capability/human capital. The rationale is that if an acquirer is strongly driven by the motive of gaining access to target capability/human capital, it is more likely to use financial incentives after acquisition, such as salary raise, to promote the retention of employees. By focusing on acquisitions that are strongly driven by the motive of gaining access to target capability/human capital, we can lower the potential influences from acquisitions with the other motives, such as corporate control, on post-acquisition involuntary turnover. To construct the variable, we first measure the average salary growth among all individuals (knowledge workers and managers) within each acquired firm. The individual salary growth is calculated by taking log-differences of individual salary (2007 price level) between the acquisition year and the year before. Second, an acquirer is identified as the one that has a strong retention motive if its acquired firm has a high level of average salary growth after acquisition. To determine whether an average salary growth is high, we use two different cut-off values: 0% and 1.32%, where 0% is used to capture the firms with a positive post-acquisition average salary growth, and 1.32%, which is the average annual inflation rate between 2007 and 2015,Footnote 9 is used to capture the firms whose average salary growth is higher than the average annual inflation rate. The descriptive statistics of the average salary growth and the variable of retention are displayed in Table 9 in Appendix 2. It is noted that there are 145 acquired firms which have missing values on average salary growth. With the retention variable, we divide the treatment group sample without missing values on average salary growth into two sub-samples. We re-estimate Model (2) with entropy balancing weights by comparing each sub-sample of the treatment group with the control group. Table 5 reports the results when the retention is measured with a cut-off value set at 0%. In the robustness check in Appendix 3, we test whether the main findings are sensitive when the cut-off value is set at 1.32%.

The left panel of Table 5 displays the results when comparing the control group with the treatment group whose acquirers have a strong retention motive. For comparison, the right panel of Table 5 displays the results when comparing the control group with the treatment group whose acquirers do not have a strong retention motive. By comparing the results between the two panels, we highlight the following findings related to the role of technological and managerial skills.Footnote 10 First, managerial skills show significantly negative moderating effects on both total departures and switch when acquirers have a strong retention motive. Second, the negative moderating effect of technological skills on switch is only statistically significant when acquirers have a strong retention motive. Third, when acquirers have a strong retention motive, technological and managerial skills affecting the relationship between acquisitions and employee departures is mainly in the form of affecting (job) switch. By contrast, when acquirers do not have a strong retention motive, technological and managerial skills affecting the relationship between acquisitions and employee departures is mainly in the form of affecting (job) exit.

We also find that managers, compared with other employees, are more likely to exit the labor market after acquisitions. Our sample contains a large share of business owners (62%) and about 21% of the owners are also managers (about 13% owner-managers in the sample). One explanation could be that the owner-managers tend to use acquisition as an entrepreneurial exit strategy. Entrepreneurial exit refers to the situation where an entrepreneur exits the business that he/she has founded (DeTienne, 2010). As discussed in Section 2.3, owner-managers may especially be affected by acquisitions and choose to leave due to status or psychological loss. To test this explanation, we divide the whole sample into two sub-samples, one including only owners and the other one excluding owners. We re-estimate Model (2) with entropy balancing weights for each sub-sample and report the results in Table 6. The left panel of Table 6 displays the results when including only owners, and the right panel displays the results when excluding owners. By comparing the results between the two panels, we find that the positive moderating effect of managerial skills on exit is only significant in the sub-sample of owners. This finding provides a support to the explanation that owner-managers tend to use acquisition as an entrepreneurial exit strategy. Furthermore, when an entrepreneur chooses to leave the company after acquisition, no matter whether voluntarily or involuntarily, he/she would show a tendency to leave by exiting the labor market for two possible reasons. First, it is common that acquirers use non-compete agreements to restrict the potential competition from key employees (Marx and Fleming, 2012). In this case, if an owner-manager chooses to leave the acquired firm after acquisition, switching to another employer or starting a new firm in a similar field could be temporarily blocked due to the non-compete agreement. It is also possible that cashed-out owner-managers reorient their career path as angel investors after acquisitions (Wright et al., 1998). In this case, the owner-manager chooses a different career path which cannot be captured by the traditional labor market data.

To summarize the main findings, first, acquisitions increase the likelihood of employees (knowledge employees and managers) leaving their current employers in general (H1). Second, post-acquisition departures of employees in acquired firms are mainly in the form of switching to another job. Third, the acquisition effects on employee departures are weaker for individuals with technological skills (H2). Fourth, the acquisition effects on employee departures are weaker for employees with managerial skills when acquirers have a strong employee retention motive (H3a, conditional on the retention motive). When acquirers do not have a strong retention motive, managers, compared to other employees, are more likely to exit the (national) labor market after acquisitions.

In Appendix 3, we conduct a set of robustness checks to test the robustness of our main findings.

5 Discussion and conclusion

This paper studies the relationship between acquisitions and mobility of knowledge workers and managers in small technology companies and how individual skills and capabilities moderate the relationship. Our results show that acquisitions increase the likelihood of knowledge employees leaving their current employers, which is consistent with the findings from previous research that focuses on target executives (Krug et al., 2014; Walsh, 1988). We also find that post-acquisition departures of employees in acquired firms are mainly in the form of switching to another job. However, the acquisition effects on employee departures are found to be weaker for individuals with technological skills. When it comes to managerial skills, the pattern is less clear-cut. The acquisition effects are weaker for employees with managerial skills only when acquirers have a strong employee retention motive. When acquirers do not have a strong retention motive, managers, compared to other employees, are more likely to exit the (national) labor market after acquisitions.

Our findings generally support the arguments that acquisition motive is a critical factor influencing post-acquisition employee turnover, and that individual skills and capabilities moderate the relationship between acquisitions and target employee departures. Moreover, we find that even if focusing only on acquirers who have a strong retention motive, acquirers would not retain all high-skilled knowledge workers but are precise about which human capital they value and invest in. Our study demonstrates that both technological and managerial capabilities are the types of human capital valued by acquirers when they have a strong retention motive. In this situation, post-acquisition employee turnover can be seen as a new job matching/selection process, where new owners acqui-hire employees with technological and managerial skills.

In addition, the retention motive allows us to better illuminate the different mechanisms of how technological and managerial skills affect the relationship between acquisitions and employee turnover. When acquirers have a strong retention motive, technological and managerial skills affecting the relationship between acquisitions and employee departures is mainly in the form of affecting (job) switch. By contrast, when acquirers do not have a strong retention motive, technological and managerial skills affecting the relationship between acquisitions and employee departures is mainly in the form of affecting (job) exit. This suggests that the retention motive plays a more important role in (job) switch than (job) exit for employees with technological and managerial skills, supporting our argument that human capital in acquired firms are actively selected after acquisitions by acquirers even if when they have a strong retention motive.

We find that acquirers tend to retain employees with technological skills regardless of whether acquirers have a strong retention motive. By contrast, retention of managers is conditional on acquirers having a strong retention motive. This shows retention of technological skills, compared to retention of managerial skills, is less dependent on the retention motive. One explanation for this could be that technological capability is a more core source of competitiveness in a high-tech SME, fulfilling the four criteria of a firm’s sustainable competitive advantage: valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and not substitutable (Barney, 1991). Regardless of whether acquirers have a strong retention motive, they have to depend on the retention of technological capabilities to get what they value from target firms.

However, managerial teams in acquired firms are comparatively easy to replace if they are not efficient, which may reflect the existence of market discipline effects (Jensen and Ruback, 1983; Manne, 1965) in acquisitions of small technology firms. This may explain why managers are found to be more likely to exit the labor market after acquisitions. Besides, it is also possible that managers tend to leave voluntarily as they are more likely to confront status or psychological loss after acquisitions. Especially, our findings show that the positive moderating effect of managerial skills on exit only exists in the sub-sample of owners. This may suggest that owner-managers tend to use acquisition as an entrepreneurial exit strategy. However, this assumption can only be fully corroborated in future studies when more precise information on the reasons behind the departure of the owners can be collected.

The present paper contributes to the literature in a threefold manner. First, this study provides new insights to the field by showing how acquisitions impact on target knowledge workers and managers in small technology firms. Extant studies have exclusively focused on post-acquisition turnover of executives in large public companies. However, the nature of acquisitions has been changing substantially over recent decades. Acquisitions of small private firms have been a popular strategy for large incumbents to source technological capabilities externally (Andersson and Xiao, 2016; Desyllas and Hughes, 2008). The main assets and competences of a small technology venture are argued to be embedded in the human capital of its founding team and key employees (Colombo and Grilli, 2005; Ranft and Lord, 2000). In this sense, knowledge workers with technological competences are supposed to be the key assets that acquiring firms strive to retain, or on many occasions, even to be the major motive that drives acquisitions (Chatterji and Patro, 2014; Coyle and Polsky, 2013). Our findings support this argument and suggest future research on post-acquisition employee mobility should go beyond management teams and give more attention to knowledge professionals, which may shed important light on post-acquisition transfer and integration processes.

Second, the present study shows that specializations of individual skills and capabilities matter for post-acquisition knowledge selection, which complements the extant research which either neglects the role of human capital or focuses only on levels of human capital (Buchholtz et al., 2003).

Third, the present study provides a systematic analysis of post-acquisition employee mobility based on large-scale data. Previous studies on this topic have depended either on small-scale surveys or on post-acquisition observations of employees in acquired firms (see, e.g., Buchholtz et al., 2003; Hambrick and Cannella, 1993; Krug and Hegarty, 1997, 2001; Walsh, 1988). A lack of control groups fails to account for the natural rate of employee turnover, which limits the interpretation and generalizability of the findings in a broader context. A lack of pre-acquisition observations fails to control for time-invariant heterogeneity between individuals, which may bias the results and limit the causal inference of the findings. Our dataset derives from the whole population of Swedish firms and contains both acquired and non-acquired firms and information both before and after acquisitions. Relying on fixed-effects models combined with an entropy balancing approach, our analysis accounts for time-invariant heterogeneity at both individual and firm levels and the potential self-selection bias. Our analysis also distinguishes between departure routes. With this information, our findings shed important light on by which route individuals leave their jobs.

One limitation of the present study is that we cannot measure acquisition motives directly. The motives behind acquisitions are a critical element which not only characterizes the nature of acquisitions but also influences post-acquisition implementation and integration processes. We believe that to distinguish the motives of the acquirers could be a critical point of departure to address the changing nature of acquisitions and disentangle the complexity of post-acquisition activities. We suggest that future research could focus on the emergence of new acquisition motives and explore how acquisitions are used innovatively to cope with the accelerating technological change.

Another limitation of the present study is that we cannot distinguish between voluntary and involuntary turnover. The distinction between voluntary and involuntary turnovers would allow us to better differentiate the different mechanisms of how acquisitions impact on employee turnover. We suggest that future research could use surveys to collect data to distinguish the two turnover routes, which will further advance our understanding of the relationship between acquisitions and employee turnover.

It should be noted that the entropy balancing approach can only account for the self-selection biases that arise from observed heterogeneity between treatment and control groups. The approach cannot handle the self-selection biases that arise from non-observed heterogeneity. That is, if there are omitted variables that predict the treatment but cannot be observed in the data, the estimates with entropy balancing weights are still biased. Although our data allows us to include a large set of individual and firm-level variables to account for the heterogeneity between employees, we cannot rule out the possibility of non-observed variables that bias the results. In this sense, we are cautious to make any causal inferences regarding the findings.

Notes

We include both high-tech and medium–high-tech manufacturing because medium–high-tech manufacturing may also include some important tech firms. Our main findings are robust when we exclude medium–high-tech manufacturing industries.

In this way, we can observe at least 1 year after acquisitions for acquired firm.

There are 1335 individuals who have worked in more than one target firm at different times. We follow them separately as they could have different occupations or firm-specific human capital.

Among the managers, about 46% have an educational background in the field of engineering, and about 10% have an educational background in the field of business administration or economics.

We have conducted a robustness check by including also firm age. The results (available upon request) show that our main findings hold.

One reason is because the changes for most of the control variables are quite marginal over the observation period, such as variables related to educational level or background. Time-invariant variables can capture the main characteristics between individuals and firms and are less prone to multi-collinearity problems. Since we use a fixed-effects model in this analysis, including time-varying variables with limited variation will increase the multicollinearity problem. Another reason is because there are more missing values for time-varying variables. Using time-varying variables we would lose many observations in regressions. Nevertheless, we have conducted a robustness check by including the time-varying variables (except for age and tenure, each of which is a perfect linear function of fixed effects). The results (available upon request) show that our main findings hold even after controlling for time-varying control variables.

All continuous variables are logged.

Based on annual rates of consumer price index from Statistics Sweden.

From Table 5, we observe that the coefficient of acquisition on total departures/switch is larger when acquirers have a strong retention motive than when acquirers do not have a strong retention motive. To test whether the coefficients of acquisition are significantly different between the two regressions, we create an interaction term between acquisition and motive and test whether the moderating effects are significantly different based on the joint sample of acquired firms (since both acquisition and motive only apply to acquired firms). The results (available upon request) show negative moderating effects on total departures / exit, but a positive moderating effect on switch. However, the moderating effect (negative) is only significant when the outcome variable is exit. That is, employees in acquired firms whose acquirers have a strong retention motive are less likely to exit the labor market after acquisitions.

References

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2010). synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105(490), 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2009.ap08746

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80(1), 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1765(03)00032-6

Albrecht, J., Bronson, M. A., Thoursie, P. S., & Vroman, S. (2018). The career dynamics of high-skilled women and men: Evidence from Sweden. European Economic Review, 105, 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2018.03.012

Andersson, M., & Xiao, J. (2016). Acquisitions of start-ups by incumbent businesses: A market selection process of “high-quality” entrants? Research Policy, 45(1), 272–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.10.002

Arora, A., Fosfuri, A., & Gambardella, A. (2001). Markets for technology and their implications for corporate strategy. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(2), 419–451. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/10.2.419

Bandick, R., & Görg, H. (2010). Foreign acquisition, plant survival, and employment growth. Canadian Journal of Economics, 43(2), 547–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5982.2010.01583.x

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Baron, J. N., Hannan, M. T., & Burton, M. D. (2001). Labor pains: Change in organizational models and employee turnover in young, high-tech firms. American Journal of Sociology, 106(4), 960–1012. https://doi.org/10.1086/320296

Becker, G. S. (1962). Investment in human capital: a theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5, Part 2), 9–49. https://doi.org/10.1086/258724

Buchholtz, A. K., Ribbens, B. A., & Houle, I. T. (2003). The role of human capital in postacquisition CEO departure. The Academy of Management Journal, 46(4), 506–514. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040642

Campbell, B. A., Ganco, M., Franco, A. M., & Agarwal, R. (2012). Who leaves, where to, and why worry? Employee mobility, entrepreneurship and effects on source firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(1), 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.943

Castanias, R. P., & Helfat, C. E. (1991). Managerial resources and rents. Journal of Management, 17(1), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700110

Castanias, R. P., & Helfat, C. E. (2001). The managerial rents model: Theory and empirical analysis. Journal of Management, 27(6), 661–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(01)00117-9

Chatterji, A. and Patro, A. (2014). Dynamic capabilities and managing human capital. Academy of Management Perspectives. 28(4), 395–408. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43822377

Colombo, M. G., & Grilli, L. (2005). Founders’ human capital and the growth of new technology-based firms: A competence-based view. Research Policy, 34(6), 795–816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.03.010

Coyle, J. F., & Polsky, G. D. (2013). Acqui-hiring. Duke Law Journal, 63(2), 281–346.

Desyllas, P., & Hughes, A. (2008). Sourcing technological knowledge through corporate acquisition: Evidence from an international sample of high technology firms. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 18(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hitech.2007.12.003

DeTienne, D. R. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.05.004

Distel, A. P., Sofka, W., de Faria, P., Preto, M. T., & Ribeiro, A. S. (2019). Dynamic capabilities for hire – how former host-country entrepreneurs as MNC subsidiary managers affect performance. Journal of International Business Studies. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00274-0

Elfenbein, D. W., Hamilton, B. H., & Zenger, T. R. (2010). The small firm effect and the entrepreneurial spawning of scientists and engineers. Management Science, 56(4), 659–681.

Eriksson, T., & Kuhn, J. M. (2006). Firm spin-offs in Denmark 1981–2000: Patterns of entry and exit. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 24(5), 1021–1040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2005.11.008

European Commission. (2009). Commission Staff Working Document. SEC (2009) 1350 final. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

Evans, D. S. (1987). The relationship between firm growth, size, and age: Estimates for 100 manufacturing industries. Journal of Industrial Economics, 35(4), 567–581. https://doi.org/10.2307/2098588

Fujiwara-Greve, T., & Greve, H. R. (2000). Organizational ecology and job mobility. Social Forces, 79(2), 547–585. https://doi.org/10.2307/2675509

Granovetter, M. (1981). Toward a sociological theory of income differences. In I. Berg (ed.), Sociological Perspectives on Labor Market, pp. 11–47.

Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171110

Grimpe, C., Kaiser, U., & Sofka, W. (2019). Signaling valuable human capital: Advocacy group work experience and its effect on employee pay in innovative firms. Strategic Management Journal, 40, 685–710. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2957

Haltiwanger, J. C., Lane, J. I., & Spletzer, J. R. (1999). Productivity differences across employers: the roles of employer size, age, and human capital. The American Economic Review, 89(2), 94–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/117087

Hambrick, D. C. and Cannella, A. A. (1993). Relative standing: a framework for understanding departures of acquired executives. The Academy of Management Journal, 36(4), 733–762. https://www.jstor.org/stable/256757

Hamilton, B. H. (2000). Does entrepreneurship pay? An empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. Journal of Political Economy, 108(3), 604–631. https://doi.org/10.1086/262131

Hellevik, O. (2009). Linear versus logistic regression when the dependent variable is a dichotomy. Quality & Quantity, 43(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-007-9077-3

Hundley, G. (2001). Why and when are the self-employed more satisfied with their work? Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 40, 293–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/0019-8676.00209

Jackofsky, E. F. (1984). Turnover and job performance: An integrated process model. The Academy of Management Review, 9(1), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/258234

Jensen, M. C., & Ruback, R. S. (1983). The market for corporate control: The scientific evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 11(1), 5–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(83)90004-1

Jovanovic, B. (1979). Job matching and the theory of turnover. Journal of Political Economy, 87(5), 972–990. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1833078

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50(3), 649–670. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1912606

Kaiser, U., Kongsted, H. C., Laursen, K., & Ejsing, A. K. (2018). Experience matters: The role of academic scientist mobility for industrial innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 39(7), 1935–1958. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2907

Kaiser, U., Kongsted, H. C., & Rønde, T. (2015). Does the mobility of R&D labor increase innovation? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 110, 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2014.12.012

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science. 3(3), 383–397. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2635279

Krishnan, T. N., & Scullion, H. (2017). Talent management and dynamic view of talent in small and medium enterprises. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.10.003

Kolev, K., Haleblian, J. & McNamara, G. (2012). A review of the merger and acquisition wave literature. In: D. Faulkner, S. Teerikangas and R. J. Joseph. (eds). The handbook of mergers and acquisitions. Oxford, Oxford University Press: Chapter 2.

Krug, J. A., & Hegarty, W. H. (1997). Postacquisition turnover among U.S. top management teams: an analysis of the effects of foreign vs. domestic acquisitions of U.S. targets. Strategic Management Journal, 18(8), 667–675. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3088182

Krug, J. A., & Hegarty, W. H. (2001). Predicting who stays and leaves after an acquisition: a study of top managers in multinational firms. Strategic Management Journal, 22(2), 185–196. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3094314

Krug, J. A., & Nigh, D. (2001). Executive perceptions in foreign and domestic acquisitions: An analysis of foreign ownership and its effect on executive fate. Journal of World Business, 36(1), 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-9516(00)00055-9

Krug, J. A., Wright, P., & Kroll, M. J. (2014). Top management turnover following mergers and acquisitions: solid research to date but still much to be learned. Academy Of Management Perspectives, 28(2), 147–163https://www.jstor.org/stable/43822047

Larsson, R. and Finkelstein, S. (1999). Integrating strategic, organizational, and human resource perspectives on mergers and acquisitions: a case survey of synergy realization. Organization Science, 10(1), 1–26. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2640385

Lavie, D. (2006). Capability reconfiguration: An analysis of incumbent responses to technological change. The Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159190

Lee, T. W., & Mitchell, T. R. (1994). An alternative approach: The unfolding model of voluntary employee turnover. The Academy of Management Review, 19(1), 51–89. https://doi.org/10.2307/258835

Lindholm, Å. (1994). The economics of technology-related ownership changes: A study of innovativeness and growth through acquisitions and spin-offs (Doctoral dissertation). Chalmers University of Technology, Department of Industrial Management and Economics.

Lowenstein, L. (1983). Pruning deadwood in hostile takeovers: A proposal for legislation. Columbia Law Review, 83(2), 249–334. https://doi.org/10.2307/1122101

Manne, H. G. (1965). Mergers and the market for corporate control. Journal of Political Economy, 73(2), 110–120. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1829527.

March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. Wiley.

Marx, M., Fleming L. (2012). Non-compete agreements: barriers to entry … and exit? Innovation Policy and the Economy. 12, 39–64. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1086/663155

Matsusaka, J. G. (1993). Takeover motives during the conglomerate merger wave. The RAND Journal of Economics, 24(3), 357–379. https://doi.org/10.2307/2555963

Moen, J. (2005). Is mobility of technical personnel a source of R&D spillovers? Journal of Labor Economics, 23(1), 81–114. https://doi.org/10.1086/425434

Moen, J. (2007). R&D spillovers from subsidized firms that fail: Tracing knowledge by following employees across firms. Research Policy, 36(9), 1443–1464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.06.004

Morrell, K., Loan-Clarke, J., & Wilkinson, A. (2001). Unweaving leaving: The use of models in the management of employee turnover. International Journal of Management Reviews, 3(3), 219–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2370.00065

Morrell, K. M., Loan-Clarke, J., & Wilkinson, A. J. (2004a). Organisational change and employee turnover. Personnel Review, 33(2), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480410518022

Morrell, K., Loan-Clarke, J., & Wilkinson, A. (2004b). The role of shocks in employee turnover. British Journal of Management, 15(4), 335–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2004.00423.x

Morrison, E. W., & Robinson, S. L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. The Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 226–256. https://doi.org/10.2307/259230

Paruchuri, S., Nerkar, A., & Hambrick, D. C. (2006). Acquisition integration and productivity losses in the technical core: Disruption of inventors in acquired companies. Organization Science, 17(5), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0207

Palomeras, N., & Melero, E. (2010). Markets for inventors: Learning-by-hiring as a driver of mobility. Management Science, 56(5), 881–895.

Park, H. D., Howard, M. D., & Gomulya, D. M. (2018). The impact of knowledge worker mobility through an acquisition on breakthrough knowledge. Journal of Management Studies, 55(1), 86–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12320

Ranft, A. L., & Lord, M. D. (2000). Acquiring new knowledge: The role of retaining human capital in acquisitions of high-tech firms. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 11(2), 295–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1047-8310(00)00034-1

Rao, H., & Drazin, R. (2002). Overcoming resource constraints on product innovation by recruiting talent from rivals: A study of the mutual fund industry, 1986–94. The Academy of Management Journal, 45(3), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069377

Rosenkopf, L. and Almeida, P. (2003). Overcoming local search through alliances and mobility. Management Science. 49(6), 751–766. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4134022

Statistics Sweden. (2016). Longitudinell integrationsdatabas för Sjukförsäkrings- och Arbetsmarknadsstudier (LISA) 1990–2013. Arbetsmarknad Och Utbildning Bakgrundsfakta, 2016, 1.

Trautwein, F. (1990). Merger motives and merger prescriptions. Strategic Management Journal. 11(4), 283–295. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2486680

Tzabbar, D. (2009). When does scientist recruitment affect technological repositioning? The Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 873–896. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.44632853

Valcour, P. M., & Tolbert, P. (2003). Gender, family and career in the era of boundarylessness: Determinants and effects of intra- and inter-organizational mobility. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(5), 768–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/0958519032000080794

Von Hippel, Paul. (2015). Linear vs. logistic probability models: which is better, and when? Statistical Horizons. URL: https://statisticalhorizons.com/linear-vs-logistic. Date of access: Sep.2, 2021.

Walsh, J. P. (1988). Top management turnover following mergers and acquisitions. Strategic Management Journal, 9(2), 173–183. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2486031

Wezel, F. C., Cattani, G., & Pennings, J. M. (2006). Competitive implications of interfirm mobility. Organization Science, 17(6), 691–709. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25146071

Wiersema, M. F., & Bowen, H. P. (2009). The use of limited dependent variable techniques in strategy research: Issues and methods. Strategic Management Journal, 30(6), 679–692. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.758

Wright, M., Westhead, P., & Sohl, J. (1998). Editors’ introduction: Habitual entrepreneurs and angel investors. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22(4), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879802200401

Wu, J. S., & Zang, A. Y. (2009). What determine financial analysts’ career outcomes during mergers? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 47(1), 59–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2008.11.002

Xiao, J. (2018). Post-acquisition dynamics of technology start-ups: drawing the temporal boundaries of post-acquisition restructuring process. Papers in Innovation Studies Paper no. 2018/12, CIRCLE Working Paper. Lund, Sweden: Lund University.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for helpful comments from Editor Rui Baptista, as well as two anonymous referees.

Funding