Abstract

In Germany, the productivity of professional services, a sector dominated by SME, declined by 40 percent between 1995 and 2014. Similar developments can be observed in several other European economies. Using a German dataset with 700,000 firm-level observations, we analyze this largely undiscovered phenomenon in professional services, the fourth largest sector of the business economy in the EU-15, which provides important inputs to the economy and has experienced substantial growth in both output and employment since the turn of the millennium. We find that changes in the value chain explain about half of the decline and that increases in part-time employment account for another small part. Contrary to expectations, the entry of micro and small firms is not responsible for the decline, despite their lower productivity levels. Further, we cannot confirm the conjecture that weakening competition has led to an increase in the number of unproductive firms remaining in the markets and that this has led to a lower average productivity.

Plain English Summary

Professional services suffered in many European countries over almost two decades a dramatic decline in productivity of up to 40 percent.

Our research adds a new piece to understanding the puzzling slowdown of the overall productivity growth. The productivity losses of professional services, a sector dominated by micro and small firms, reached between 1995 and 2014 up to 40 percent in several European economies, while this industry shows at the same time a substantial growth of almost 50 percent in the number of persons employed since the millennium. This study examines several possible explanations for the productivity losses. About half of the decline can be attributed to changes in the value chain. Another small part is due to the increase of part-time employment. Against expectations, the massive influx of new firms, which are mostly micro and small firms, is not at the core of the problem. We also find no evidence for a weakening of competitive pressure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The decline in labor productivity growth is a central concern underlying the slowed economic progress in many industrialized countries. Potential explanations range from measurement problems (Ahmad et al. 2017; Syverson 2017; Byrne et al. 2016), a lack of competition (De Loecker et al. 2020), a lack of knowledge diffusion (Andrews et al. 2015, 2016, 2019), decreasing returns to R&D (Bloom et al. 2020; Malerba and Orsenigo 2015; Gordon 2012), declining business dynamics (Bijens and Konings 2018; Alon et al. 2018; Decker et al. 2016), expansive monetary policy (Gropp et al. 2020; McGowan et al. 2017), to the structural changes toward more services (Nordhaus 2021; Hartwig and Krämer 2019; Duernecker et al. 2016; Oulton 2013, 2001), among others. In this context, the productivity development of one major part of the service sector, professional services, an industry dominated by micro and small firms, stands out: professional services not only experienced a reduction in labor productivity growth, but a severe drop in productivity over two decades. This decline is observable in several continental European countries and amounts, inter alia, to 40 percent in Germany in the 1995 to 2014 period before it started to slightly recover.

This dramatic decline is worrying for various reasons. Professional services carry considerable economic weight. With a growth of almost 50 percent in the number of persons employed since the millennium, this sector shows substantial growth among all sectors of the European business economy.Footnote 1 Thus, they are particularly important for the labor market. Furthermore, nearly 10 percent of total value added of the business economy is produced by professional services, which made them the fourth largest sector in the EU15 in 2017. Moreover, as the professional services industry provides important intermediate inputs to the whole economy, negative productivity effects in this sector have critical repercussions for the productivity of the rest of the economy.

This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to empirically assess various potential causes for the productivity decline in professional services (Owalla et al. 2021). Thus, it adds to the understanding of the overall slowdown in productivity growth. Specifically, we analyze whether, and to what extent, composition and competition effects are the driving forces behind the falling labor productivity. The former includes changes in the workforce, the vertical supply chain, and the firm size composition of the sector. During the observation period, professional services experienced a massive entry of small and micro firms. At the same time, empirical studies show that micro and small firms have lower productivity levels than large firms (Medrano-Adán et al. 2019; Moral-Benito 2018). Therefore, we study whether the growing number of micro and small firms depresses aggregate productivity growth in professional services. Firm size is also relevant when considering potential competition effects. The literature assumes a positive relationship between productivity and competition (Backus 2020; Grullon et al. 2019; Hsieh and Rossi-Hansberg 2019). Declining competitive pressures could lead to unproductive firms remaining in the market or to reducing overall incentives to increase productivity. Using firm-level markups over marginal costs as a proxy for market power, we analyze whether competitive pressure has declined during the observation period and whether it had dampening effects on aggregate labor productivity. We distinguish between firms of different size classes in our analysis, as micro and small firms might face a different competitive environment than medium and large firms.

In our analysis, we focus on Germany using an official and representative firm-level dataset with 706,140 observations for the 2003 to 2017 period collected by the Federal Statistical Office. We find that about half of the productivity decline can be explained by changes in the firms’ vertical integration and the growing usage of intermediate goods and services, while the increase in part-time employment is responsible for a further minor part of the decline. Against expectations, the massive entry of small and micro firms plays no role in explaining the decline in aggregate productivity. Put differently, micro and small firms are not to blame for the drop in productivity in professional services. Moreover, markups decreased in the majority of the industries, suggesting that competitive pressure rather increased over the observation period and is unlikely to have caused the productivity decline.

As the picture of the main drivers of this massive drop remains incomplete, we close our analysis by outlining further explanations that need to be evaluated by future research. Suggestive evidence points to price mismeasurement in some of the industries, which affects measured labor productivity growth. Another question that deserves further attention and requires appropriate data sources is whether increasing complexity and bureaucracy necessitates additional labor input, this way driving average labor productivity down.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The subsequent section describes the productivity development in professional services and the repercussions on aggregate productivity development in the whole business economy. Section 3 discusses potential reasons for the productivity decline and explains the empirical strategy. Section 4 presents the results. The findings are discussed in Section 5 and 6 concludes.

2 Productivity decline in professional services and its impact

2.1 Productivity development of professional services in Europe

Professional services are a part of business services and comprise a variety of professions; including, among others, lawyers, consultancy, advertising, leasing activities, and travel agencies (see Appendix A). The decline in labor productivity in this sector is not just a German phenomenon, it is observed in several European economies. Figure 1 shows the development of labor productivity in professional services between 1995 and 2017, the longest period for which data are provided by Eurostat. The figure reveals that labor productivity in 2017 is below the level of 1995 in eight of thirteen countries and has significantly increased only in Sweden. Thus, in many economies, professional services are less efficient these days than in the late 1990s. In some countries, the loss in productivity is strikingly large: Greece, Luxembourg, Germany, and Italy stand out, with respective declines of 46 percent, 44 percent, 37 percent, and 35 percent by 2017; with the latter two among the Europe’s economic heavyweights. These countries are accompanied by Finland, Denmark, and Portugal. However, professional services in the latter two states managed to recoup some of their losses in the years after 2009. This points to another pattern in the data: toward the end of the observation period, we observe stagnation or modest recovery in some countries.

Taking the example of Germany, we can identify two opposing trends that led to the measured decline in labor productivity in Europe. Professional services experienced the second highest employment growth in the German business economy between 1995 and 2017, with the number of employees more than doubling over this period. As a result, the share of professional services in total employment rose from 5.2 percent in 1995 to 9.6 percent, making professional services the 4th most important sector in the business economy after manufacturing, trade, and administrative and support services.Footnote 2 On the other hand, output, as measured by value added, increased only at the same rate as in the rest of the economy (see Appendix D, Fig. 11, left panel). As a result of these two opposing trends, aggregate labor productivity in professional services — defined as real value added over employees — decreased by about 37 percent until 2017, which is the most pronounced decline among all sectors of the German business economy (see Figs. 13 and 14 in Appendix D).

2.2 The effect on overall productivity growth in the economy

This massive decline affected productivity growth for the whole economy, as the aggregate productivity growth is an employment-weighted average of labor productivity growth in all industries. Through a simple decomposition approach, we show how the productivity decline in professional services restrains labor productivity in the overall economy. We follow De Loecker et al. (2020) and decompose aggregate labor productivity growth in the German business economy between 1995 and 2017 at the sector level between professional services and the rest of the business economy. This allows us to determine how much of the productivity growth is attributable to productivity gains within sectors (within-industry effect), to labor force reallocation between sectors (between-industry effect), as well as to joint changes in productivity and labor force reallocation (interaction effect). The formula is given by

with \(s_t^i=(L_t^i/ L_t)\) denoting sector i’s labor share in the business economy at time t, \(\Delta s^i\) is defined as \(\Delta s^i = s^i_{2017}- s^i_{1995}\) and \(\Delta LP^i\) as \(\Delta LP^i = LP^i_{2017}- LP^i_{1995}\). The results are listed in Table 1. We observe two main effects: The shift of the labor force toward professional services positively contributed to productivity growth between 1995 and 2017 since average labor productivity in professional services is higher than in the rest of the economy (between-industry effect). The productivity decline in professional services, however, restrained overall productivity growth. While productivity growth in the rest of the economy was positive, shifting average productivity by hypothetical 15,848 EUR/employee — holding the labor force allocation constant in its 1995 values — the productivity decline in professional services, ceteris paribus, reduced the growth potential of overall labor productivity by 13 percent; i.e., 1,981 EUR/employee (within effect). In addition, the fact that parts of the labor force were reallocated from sectors with positive average productivity growth toward a sector with declining productivity, negatively affected overall productivity growth (interaction effect).

Therefore, the existence of a sector where productivity growth in many European countries is not only slowing down but actually negative constitutes another explanation for the sluggish aggregate productivity growth observed in European countries. These results might be seen as a confirmation of theories explaining the slowdown in productivity growth by a structural change toward services (Nordhaus 2021; Duernecker et al. 2016; Oulton 2013, 2001). The so-called Baumol disease postulates inherently lower productivity growth potentials in services. We show that productivity can even be negative in some service sectors, further exacerbating the productivity effect of a structural shift toward services. However, note that the productivity development in professional services is not representative of productivity growth among all service sectors and that some services — like information and communications — accumulated extraordinary productivity gains since 1990 (Fig. 14 in Appendix D).

A productivity decline in an important supply industry can also restrain productivity growth in the rest of the economy if the supplying firms deliver less output or output of lower quality for the same unit price. Furthermore, knowledge dissemination could be reduced if, as a consequence, the set of firms contracting for professional services shrinks or prevents other firms from taking full advantage of the knowledge embedded in the services that professional service firms provide. In fact, professional services, together with transportation, are the second most important industries after manufacturing with respect to the provision of intermediate goods and services to other industries. In 2016, professional services provided 10 percent of all intermediate goods and services from domestic production used in the German economy against 27 percent provided by manufacturing (Table 6 in Appendix C). In absolute terms, the largest share of professional service production outside of business services goes to manufacturing, finance, real estate, and trade, which combined contributed one-half to total domestic value added creation in 2019. Hence, the productivity decline in the professional services industry since the 1990s may have dampened aggregate productivity growth, as professional services provide fundamental services for a wide range of industries.

In sum, we find that professional services experienced a significant and continuous deterioration of labor productivity over a long time span. It can be considered the worst performing sector in the German business economy, whose productivity loss has had a measurable negative effect on productivity growth in the entire economy. Furthermore, the sectors’ crucial role as a supplier of intermediates in the economy might have further negative effects on aggregate productivity growth, even though these effects are difficult to quantify.

3 Potential reasons for the productivity decline and estimation strategy

This study assesses various factors that may explain the decline of productivity, starting with explanations that we summarize as composition effects (Section 3.1). We then examine the role of the market environment, as the decline in productivity might be driven by changes in competition (Section 3.2). The analysis uses official German data at different levels of aggregation with a focus on the firm, industry, and sector levels. The firm-level data stems from the annual survey of service firms conducted by the Federal Statistical Office (AfiD-Panel Dienstleistungsunternehmen), available for 2003 to 2017, which contains between 29,000 and 65,000 observations per year in professional services.Footnote 3 The advantage of these data is that it is a representative sample of all German professional service firms. The data contain detailed information on various firm characteristics, including value added, spending for intermediates, investment, turnover, and employees. Data at the industry (NACE 2-digit) and sector level (NACE 1-digit) is taken from the national accounts, which are based on the same firm-level data and have been projected to the national level by the Federal Statistical Office.

3.1 Composition effects

A key question of the analysis concerns the composition of the firm population in terms of firm size. Between 2004 and 2017, the number of firms in professional services more than doubled (see Appendix C, Table 4). Most of these new entrants were micro- and small-sized firms. It is an established fact that larger firms are, generally, more productive (Medrano-Adán et al. 2019; Moral-Benito 2018). It is argued that the firm entry and growing number of micro and small firms might be a driver of the productivity decline (Flegler and Krämer 2021). Therefore, we examine whether changes in the size composition of the industry account for the decline in aggregate labor productivity. In other words, we test whether the small and micro-sized firms are at the heart of the productivity problem in professional services. To analyze this question, we apply a simple decomposition method exploiting the fact the aggregate labor productivity growth is an employment-weighted average of productivity growth in different size classes. The underlying hypothesis of composition effects is that a change in the composition of the industry is causing the decline in productivity, i.e., that the decline is a mere statistical effect. Inter alia, if all firms keep their productivity constant over time but there are more small firms entering the market, the aggregate productivity would decrease without any economic reason. Thus, decomposing productivity growth among size classes allows us to determine whether the productivity decline is a mere statistical effect or whether fundamental changes took place in the sector that affected all firms in this industry (e.g., changes in the market structure and changed production processes).

Formally, we follow (De Loecker et al. 2020) and decompose productivity growth by firm size into a within-size-effect that measures the contribution of each size class’ internal productivity changes, a between-size-effect that accounts for labor force reallocation between firms of different size, and an interaction effect that measures the joint impact of both. We distinguish between micro-sized firms (micro) and small to large firms (sml). The formula is given by

with \(s_t^i=(L_t^i/L_t)\) denoting size class’ i’s labor share in professional services at time t, \(\Delta s^i\) is defined as \(\Delta s^i=s^i_{t_1}-s^i_{t_0}\) and \(\Delta LP^i\) as \(\Delta LP^i=LP^i_{t_1}-LP^i_{t_0}\). Due to the NACE revision in 2008, we consider the periods 2004 to 2007 and 2008 to 2017 separately. A negative between-size effect would indicate that the disproportional increase of micro-sized firms negatively contributes to productivity growth through labor force reallocation from high-productive to low-productive firms.

The second composition effect concerns changes in the workforce. During the observation period, the share of part-time workers in Germany nearly doubled from 16 percent in 1995 to 29 percent in 2017 (Destatis 2021a). Detailed data for professional services is available from 2008 onwards. There, part-time work increased from 15 percent in 2008 to 24 percent in 2017 (Destatis 2021b). Using descriptive analysis, we test whether the sharp increase in employment observed in professional services is explained by the growing importance of part-time work. If so, the numbers for labor productivity — which are based on the number of employees — would hardly be comparable over time and the decrease in productivity would reflect changes in the composition of the workforce instead of declining competitiveness.

A third potential explanation focuses on changes in the value-added chain. The vertical integration of production has declined throughout the economy over the past decades. This is illustrated by the fact that the average expenditure for intermediates per employee in the German business economy has risen by 46 percent between 1995 and 2017; in some sectors, such as finance and IT, it has risen by up to 300 percent (see Appendix D, Fig. 12). If the use of intermediates has grown faster than gross output over time, labor productivity — defined as the ratio of value added, i.e., gross output minus intermediates, to employees — must, ceteris paribus, decrease. Using descriptive analysis, we evaluate whether the slow growth in value added is due to an increased usage of intermediate goods and services as well as whether labor productivity would follow a similar trend if it was calculated with the gross production value instead of value added. Comparing both measures reveals the extent to which changes in the composition of value added are responsible for the decline in productivity.

3.2 Changes in competition

The conventional view in the economic literature is that competition and productivity are positively linked, i.e., an increase in competitive pressure reduces managerial slack, fosters innovation, and reallocates resources from less productive firms to more productive firms (Backus 2020; Grullon et al. 2019; Hsieh and Rossi-Hansberg 2019). If the relationship also holds in the inverse case, a decrease in competitive pressure would affect aggregate productivity in a negative way by facilitating managerial slack, reducing the need for innovation, and allowing unproductive firms to stay in the market. The second part of the analysis examines how competition has changed over time and whether these changes might have been the driving force for the observed decline in productivity.

3.2.1 Market structure

Markets for professional services differ to some degree from markets in other industries, since parts of the offered services can be considered credence goods. This means that even after experiencing the product, the buyer cannot fully ascertain its quality and, in most cases, firms provide both the diagnosis and the treatment (Emons 1996). The results are customer-tailored solutions and markets that are characterized by a high degree of price and quality intransparency (Dulleck and Kerschbamer 2006; Mimra et al. 2016). For example, customers of legal services have difficulties in judging the quality of a legal advice or the necessary steps for taking their cases to court. In that sense, it is often difficult for the customer to evaluate which parts of the performed service are really necessary, but also whether relevant treatments are not performed. Furthermore, many of these markets are highly localized, often with little international competition due to language barriers and specific national rules. Finally, in many countries, market entrance in some of the professions is not as straightforward as in others. In Germany, persons wishing to work as a lawyer, architect, certified public accountant, tax counselor, or veterinarian must register with the relevant national association or chamber before entering the market.

To remedy some of these aforementioned issues, the German legislature decided to regulate output prices for certain professional services. These comprise legal services, architectural and engineering activities, tax counseling, and veterinary activities. For these professions, the legislature publishes detailed fee schedules consisting of two-part tariffs with a lump sum fee for specific treatments and a variable fee depending on the value of litigation or construction.

Since the 2000s, the European Commission pushes for intensifying competition in professional services; for instance, as part of the EU Internal Market Directive in 2006 and with several infringement procedures against Germany for alleged violation of EU competition rules (EC 2015, 2018b, c, a). The consequences are an increasing number of exemptions from the price regulation (e.g., extralegal activities, allowance for side agreements with time-based rates, and lump sum payments) and the suspension of the fee schedule for architects and engineers following a ruling by the European Court of Justice in 2019.

In sum, competition may be hampered in parts of German professional services by the fact that several of the services can be characterized as credence goods, by the fact that markets are highly localized, and because of barriers to entry. Although European policy aims at fostering competition in services, it is unclear how successful these policies are.

However, while regulation is important for a number of professional services, this does not mean that all German professional services are regulated. The regulated industries account for about 40 percent of turnover, half of the employees, as well as half of total value added that is created in this sector. Quite a number of industries, namely advertising, management and consultancy activities, accounting activities, as well as research and development activities, are unregulated meaning that prices are set freely.

3.2.2 Estimation of markups

To measure changes in competition, we analyze the evolution of firm-level markups. Markups are defined as the margin between output price and marginal costs of production (Hall 1988; De Loecker 2011b). When competition is fierce, firms usually set output prices close to marginal costs plus some margin for covering fixed costs. Decreasing competitive pressure allows firms to increase the output price beyond that level and to generate additional profit margins. De Loecker et al. (2020) show that markups in the US have increased by 40 percent between 1980 and 2016, arguing that the rise in markups translates an increase in market power and reduced pressure from competitors. Studies for Germany show more nuanced results: Ganglmair et al. (2020) find that markups only moderately increased between 2007 and 2015, exhibiting a rather unstable trend in the service sector. Their measure of services comprises not only business services but also transport (NACE category H), accommodation and food (category I), information and communication (category J), as well as real estate (category L). Furthermore, their dataset is biased toward large firms and, thus, is not fully representative of the German professional service industries, which is dominated by micro-sized firms (see Appendix C, Table 4).

We estimate markups in the professional service industries applying the approach developed by De Loecker and Warzynski (2012) and De Loecker et al. (2020) with industry-specific production functions at the 2-digit-level (see, e.g., Ganglmair et al. 2020; De Loecker et al. 2020; Andrews et al. 2019; De Loecker et al. 2016, for further applications). Assuming a Leontief production function in intermediate goods and services \(M_{it}\) and two other inputs, capital \(K_{it}\) and labor \(L_{it}\), an estimate for firm-level markups is given by

with \((p_MM_{it})/S_{it}\) denoting the firm’s expenditure share for intermediate goods and services in the gross production value, \({\hat{\epsilon }_{it}}\) is an estimate for the output measurement error, and \(\hat{\mu }^l_{it}\) stems from the second term in the Leontief production function. It is defined as the output elasticity for labor times payroll over gross production value and corresponds to an estimate for the markup over marginal costs in a gross production values function with the two inputs labor and capital. We provide further details and an intuition for the estimation routine in the Appendix, Section B.

4 Results

4.1 Composition effects

The vast majority of new entrants in the market are micro and small-sized firms: Their number increased by more than a quarter of a million between 2004 and 2017 (see Table 4 in Appendix C).Footnote 4 In addition, we find that average productivity decreases with firm size: micro firms in professional services are significantly less productive than small firms, which in turn are less productive than medium-sized companies etc. (Fig. 2). The strong growth in the number of small and micro firms together with their subdued labor productivity might underly the reduced aggregated sectoral productivity. Therefore, we analyze whether changes in the average firm size could explain the negative trend in aggregate productivity growth by decomposing productivity growth according to Eq. 2.

Table 2 presents the results. The last row shows that labor productivity fell by a total of EUR 2,373 per worker between 2004 and 2017. However, the between-size effect is positive, i.e., the changes in composition of the firm population between 2004 and 2017 had a positive impact on labor productivity growth. The reason is that the number of firms in the different size categories increased at the same pace (see Fig. 3) and that the increase of the larger firms was accompanied by a relatively larger increase in persons employed in large firms. Therefore, the share of persons employed in micro firms actually decreased over the years despite the massive entry of micro firms. Hence, the labor force reallocation positively impacted productivity growth. The results hold true if we join micro and small firms within one category (see Table 5 in Appendix C). Thus, the decomposition analysis reveals that the massive entry of micro-sized firms did not cause the decline in aggregate productivity.

Another potential cause for the measured productivity decline might be the growing importance of part-time work, which changes the composition of the workforce. In order to verify the relevance of this explanation, we contrast productivity growth based on the total number of hours worked with productivity growth based on the number of employees. Figure 4 shows that labor productivity based on hours worked performed slightly better between 1998 and 2008, but continues to deteriorate as well. The gap between both productivity measures widens toward the end of the observation period, cumulating in a difference of 5 percentage points in 2017. However, against a total decline of 37 percentage points between 1995 and 2017, this difference remains small. Hence, we conclude that the composition of the workforce in professional services, i.e., the growth in part-time work, only explains a minor part of the downward trend in labor productivity.

Labor productivity based on hours worked vs. number of employees. Source: Destatis (2020b)

Finally, we analyze whether changes in the vertical integration of production plays a role in the decrease of productivity. Figure 5 compares the evolution of productivity based on value added with productivity based on the gross production value for the 1995 to 2017 period. Both time series follow a similar trend until 2013, but the decline is less pronounced with gross production value (−18 percent) than with value added (−39 percent) and the gap between them widens over time. In other words, the increasing use of intermediate goods was not accompanied by a more parsimonious use of employees, leading to productivity losses that increased throughout the observation period. Therefore, vertical disintegration within firms plays a substantial role in the productivity decline, accounting for about half of the productivity loss between 1995 and 2017.

Labor productivity based on value added vs. gross production value. Source: Destatis (2020b)

Using sectoral input-output data provided by the Federal Statistical Office allows us to shed more light on the nature of the intermediate goods and services consumed by professional services firms. In addition to the high internal interdependence, the most important inputs in professional services come from the IT sector, e.g., in the form of software, IT system administration, and web-related programming services (Table 7 in Appendix C). In the R&D sector, inputs from the manufacturing industry also play a major role, while expenses for licenses and usage fees from various media outlets are particularly important in the field of advertising and marketing. Among all sections of professional services, we observe proportionally high expenses for rents. Yet, the share of rents in total intermediate expenditure decreased between 2004 and 2017 in all size classes (Fig. 6). Hence, although important in absolute terms, rents and leasing costs do not drive the increased expenditure of intermediate goods and services. Unfortunately, the microdata do not allow us to disentangle the expenditures for intermediate goods and services any further, thus we cannot analyze their evolution over time in more detail.

4.2 Competition and market structure

A little less than half of the productivity decline is still unexplained. Therefore, we also address the question whether declining competitive pressure could have reduced incentives to eliminate slack in production or could have allowed unproductive firms to stay in the market. To measure competitive pressure, we analyze the evolution of average markups over marginal costs as an indicator for the firms’ market power. We removed the top and bottom 1 percent of the observations to avoid having results that might be driven by outliers.Footnote 5

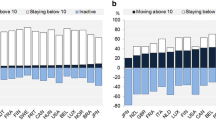

We find that the markups in the regulated industries, such as legal and accounting services or architecture and engineering activities, are, on average, higher than in the unregulated industries (Fig. 7a). However, they follow the same trend over time: markups in the regulated and unregulated industries fell by an average of 6 percent between 2004 and 2014 (Fig. 7b). Zooming more closely into the industries, we see that markups declined in all industries through 2015 with the exception of management and consulting services, where they remained fairly stable, as well as architecture and engineering activities, where they increased over time (Fig. 15b in Appendix D). The decreasing pattern seems to be consistent across firm size. If we weight the mean by the gross production value, the picture does not change much (Fig. 16 in Appendix D).

However, plotting the markup by firm size reveals another interesting aspect (Fig. 8). We find that micro firms have the highest markups, which is in line with the results of Ganglmair et al. (2020). The latter suggest that smaller firms are less exposed to competitive pressure as their business focus is narrower (niche firms). As in their study, the observation of a gap between small and large firms is strikingly consistent across industries in our analysis (see Fig. 17 in Appendix D). This makes us draw a different conclusion. The labor share in micro firms could be downwardly biased if owners working in the firm do not or only incompletely report their own wages.Footnote 6

In sum, we find evidence for a decline in price margins over marginal costs within all size classes. Taken together with the observed substantial entry into the market since 1995, these factors largely indicate that competitive pressure in professional services has increased since the 2000s. This is at odds with the significant fall in labor productivity within all size classes and suggests that changes in competitive pressure are unlikely to explain the observed decline in labor productivity.

5 Discussion and outlook

5.1 Hampered substitution

In the previous analysis, we show that when we consider sales per employee, the decrease in productivity is only half as strong as the decrease in productivity when measured in value added per employee. This is a puzzling result because, in the long run, the substitution of in-house production by intermediates should be followed by one of two possible adjustment strategies: Either firms lay off parts of the workforce that are no longer needed or firms increase sales, using the freed workforce productively in other parts of production that remain in-house.Footnote 7 Of course, if sales growth is sufficiently strong, the total workforce may also grow despite an intensified use of intermediates. This has been the case for several decades in the German automobile industry and in information and communication services. It remains an open question for future research why firms in professional services, on average, have evidently increased employment so much and simultaneously raised their consumption of intermediate goods and services despite a modest development in sales. We address this issue also in the following subsection.

5.2 Increasing complexity, bureaucracy

Besides highlighting the relevance of intermediates in explaining the decrease in value added per employee, Section 4.1 also reveals that total sales per employee have been declining for a long time. This decline amounts to 18 percent between 1995 and 2017 (see Section 4.1, Fig. 5). In fact, professional services as well as administrative and support services are the only sectors apart from real estate that experienced negative sales by employee growth over that period (Fig. 18 in Appendix D). Since we deflated sales and purged them of any price effect, it means that physical output per employee has decreased.

A decreasing average output by employee is difficult to conceive of for many of the respective professions, such as lawyers, engineers, and auditors. Certainly, work in some fields might have become more complex, in particular in R&D, where some researchers argue that ideas are becoming harder to find (Bloom et al. 2020). However, the physical productivity of the employees will not have decreased, i.e., there is no reason to believe that an engineer in the year 2020 is less capable than in the year 1995. It is more probable that the increased complexity of the work creates additional workload that either slows down the production process (e.g., stricter environmental and safety regulations complicate the planning process of bridges or buildings) or requires additional staff (IT system administrator, social media officer, funding administrator). It is important to note that the increased complexity not only relates to possibly increased government regulations, but also includes the consequences of digitization (e.g., IT department, software) and the Internet age (e.g., website, social media). Another source of complexity could be changed demand patterns, i.e., higher customer expectations (Flegler and Krämer 2021).

But why do professional service firms not sufficiently innovate their business routines to become more efficient at handling the (presumably) increased complexity of tasks and why are they unable to make efficient use of intermediate goods and services (see Section 5.1)?Footnote 8 One potential reason could be insufficient investments into human capital. Specifically, investments into on-the-job training could be crucial in that context as they would allow firms to increase their absorptive capacity (Black and Lynch 2001; Cirillo et al. 2021). The importance of investments into human capital for achieving productivity gains is documented in various settings (Bosma et al. 2004; Black and Lynch 1996; Boothby et al. 2010; Audretsch et al. 2020). It appears that in the service sector, technological innovations alone do not bring about a breakthrough if they are not accompanied by the ability to absorb these technical innovations (Runst and Thomä 2021). Thus, our paper contributes to the discussion on lacking (human capital) investments to leverage the benefits of digitization (Siachou et al. 2021; Cirillo et al. 2021).

The increased complexity of the work is not just confined to professional services, of course, but it could be more relevant in knowledge-intensive services than in manufacturing or low-skilled services. Output per employee in manufacturing will, to a much greater extent, be driven by the capital used, i.e., by technological innovations. Ancillary services and regulation might be of less relevance in construction, gastronomy, or cleaning. It remains an open question, though, why other knowledge-intensive services, like finance, real estate, or communication and information, should have been less affected or whether they better managed to cope with the growing complexity. One potential reason could be that knowledge dissemination between firms works out better in these sectors and that these firms invest more in process innovation.

5.3 Past excess returns

The second part of the analysis focused on the state of competition in the markets, as weakened competition could be another source for aggregate productivity decline. However, the results indicate a tendency for increasing rather than decreasing competition. Although this finding contrasts with our initial expectation regarding the cause of the productivity decline, it is an inherently interesting result. It might be seen as evidence that past EU policies have succeeded in fostering competition in these particular markets following the EU Service Directive in 2006. Future research should look more deeply into entry and exit dynamics within these markets and study whether the implementation of the EU policies indeed allowed more firms from abroad to enter the German market, or whether it is mostly competition among domestic firms that has increased. Unfortunately, our data does not allow for such an analysis.

A second question that emerges is why productivity has not increased due to more intense competition. A possible explanation could be that competition was so severely restricted in the past that firms were able to generate massive excess returns. If these were large enough, firms could have achieved high levels of value added and subsequently high values of labor productivity. If markups then decrease over time due to fiercer competition, value added per worker would also decline. Hence, one interpretation would be that the decreasing labor productivity is actually the result of fiercer competition. However, there is little empirical evidence for this. For the argument to be true, we would expect markup levels to have been much higher in professional services than in other industries in the past. We find no such evidence, at least not for the period for which microdata is available. Figure 8 in Section 4.2 shows that average markups have not been abnormally high in the past, and were generally below 1.1 for most of the firms, except for micro firms.Footnote 9

5.4 The role of prices

Finally, we return on the price deflation routines used to compute deflated monetary values in order to make them comparable over time. Unless physical inputs and outputs are available, it is standard to analyze productivity using deflated values. In production function estimations, the mismeasurement of prices can lead to biased output elasticities and, thus, to incorrect productivity estimates. Klette and Griliches (1996), Foster et al. (2008), Katayama et al. (2009), De Loecker (2011a), Collard-Wexler and Loecker (2016), Grieco et al. (2016), and De Loecker et al. (2016) provide detailed discussions on this issue for production function estimations. Yet, we will show that labor productivity is also affected by the chosen price deflator and we will explore the role of price corrections in the assessment of labor productivity growth in more detail.

The present analysis either directly used the deflated values at the industry level, as published by the Federal Statistical Office, or it deflates nominal values (e.g., in the micro data) with the official price indices at the two-digit industry level. The latter are also published by the Federal Statistical Office.

The collection of prices to calculate the price indices in professional services is notoriously difficult due to the market characteristics discussed in Section 3.2.1. Detailed price indices per 4-digit industry are only publicly available for a subgroup of industries within professional services. Information for activities of head offices (NACE division 70.1), bookkeeping (divisions 69202 and 69204), R&D (division 72), other activities (division 74), and veterinary activities (division 75) are missing. Furthermore, the time series only start in 2003 and 2006. By contrast, aggregate data for professional services are available from 1991 onwards.

Figure 9 plots the evolution of the published price indices against the inflation rate and the deflator time series for value added. The jump of the price indices in the regulated industries (legal services, tax accounting, architecture and engineering activities) between 2012 and 2014 stems from an adjustment of the fee schedule with an average increase of 10 to 20 percent.Footnote 10 The figures reveal two key insights. First, it becomes clear that output prices in professional services — as published by the Federal Statistical Office — increased more slowly than the inflation rate up to 2012. This suggests that real income in these industries declined over the years. The adjustment of the fee schedule in 2013 resolved this issue for the regulated industries, whose price erosion was overcompensated by the reform. Second, the deflator time series for value added (black line) develops close to the producer price indices of the regulated industries (Fig. 9a), but more strongly than the price indices of unregulated industries (Fig. 9b). This could indicate that the official price indices for value added rely to a larger extent on the easily available prices for the regulated sectors, despite the fact that these sectors account for only 40 percent of the total turnover, half of the employees, and half of total value added (see section 3.2.1).

Producer price indices in professional services. Source: Destatis (2020c)

To further examine this, Figure 10 compares nominal and real labor productivity growth. For convenience, we report both the officially deflated values and CPI-adjusted values to approximate real values. Figure 10a reveals that all measures of labor productivity show a similar trend until 2009, after which nominal labor productivity starts to significantly recover. Thus, a first and important finding is that labor productivity in professional services has fallen for ten continuous years, regardless of whether nominal or real value added is used. Hence, price indices and price corrections cannot be the cause for the decline in productivity in this period.

Labor productivity growth in professional services, different deflator. Source: Destatis (2020b)

Second, there is a strong divergence in developments after 2009 (Fig. 10b). This divergence is clearly more pronounced if labor productivity is calculated using officially published real value added than when deflating nominal value added with the CPI. Together with the observed close proximity between value added deflators and the PPI of the regulated industries, this raises the question of whether the officially published price corrections for value added are too large. In other words, the negative labor productivity growth after 2009, based on real value added, might be exaggerated to a certain extent.

6 Conclusion

We provide first evidence on the dramatic decline in labor productivity of up to forty percent since the 1990s for German professional services, which includes, among others, architecture and engineering services, marketing research, and tax and legal consulting. As of 2017, the firms in this industry work with an efficiency that is more than a third lower than in the mid-1990s. Thus, the negative growth in labor productivity in this industry, which is also observed in several other Western European economies, contributes to the general analysis of why overall productivity growth has slowed since the 1980s — an issue that is a source of increasing concern for politicians and academics.

Half of the surprising decline in productivity among professional services is explained by changes in the firms’ vertical integration and the growing use of intermediate goods and services, while the increase in part-time employment is responsible for a further minor part of the decline. However, the underlying causes of this development remain unclear. It is likely that it is increasingly challenging for these firms to provide their services; for example, due to more red tape, increased regulatory requirements such as environmental requirements for engineering services, and increased customer requirements in consulting. Furthermore, fixed costs could also be increasing, which might be only inadequately covered by the price index for intermediate goods.

Interestingly, larger companies, where the effect of the growing usage of intermediate goods may also have a greater impact, face similar productivity losses as small and micro firms. Thus, there is no evidence supporting the expectation that small and micro firms are the primary drivers of the productivity decline in this industry. Additionally, the assumption that the productivity loss is a consequence of reduced competition in this industry could not be confirmed. Rather, our analysis indicates a tendency for intensified competition. The latter finding might also explain why labor productivity in professional services stabilized since 2014. Although this study provides some explanations for the productivity decline, our analysis remains incomplete with respect to the underlying causes of this decline. To this end, additional research is needed.

Notes

The business economy captures economic activities in which market forces are predominant. Statistically, this includes all NACE Rev. 2 sections from Mining (B) to Administrative Services (N), with the exception of some financial branches. See also https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Business_economy

Perhaps surprisingly, administrative and support services (NACE N) experienced the strongest employment growth among all sectors of the business economy. However, this sector includes temporary agency workers and, thus, is not comparable to the rest of the economy, as its employees work in different brunches of the economy but are statistically part of NACE section N.

Note that professional services (NACE M) did not exist as a proper NACE category before 2008. At that time, professional service firms were instead scattered across other categories or were not part of the industry classification at all. In fact, one of the main reasons for the ISIC/NACE revision in 2008 was the recognition of the rising importance and diversity of service firms, which up to that point were insufficiently identifiable in NACE. We use Dierks et al. (2019) to identify professional service firms before 2008.

The EU size class definition is used. See https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/sme-definition_en

We also had to discard observations after 2015 since a new sample design in 2016 makes observations hardly comparable over time. The problem is mostly resolved when using population weights, which were used in the labor productivity graphs (Figs. 2 and 3) as well as Table 2 and Appendix C Tables 4 and 5. Unfortunately, it is not possible to use population weights in the markup estimation routine.

While this phenomenon could, in principle, occur among larger firms, the distorting effect on labor share will be particularly pronounced for micro firms. First, because their wages are relatively more important in the total payroll due to a smaller workforce and, second, because micro-business owners are more likely to work in the firms. A downward bias in the labor share causes an upward bias in the markup estimate as can be seen from Eq. (7) in Appendix B. Self-employment is relatively widespread in professional services, particularly in the context of micro firms with up to 10 employees, which would explain the gap between micro firms and firms of other size classes in our results.

Of course, it does not need to be the identical workforce. Some of the employees no longer needed might lose their jobs, e.g., because they lack the necessary qualification, while firms simultaneously hire new employees to cope with growing sales.

For instance, software and IT infrastructure should support the firms in their core business and speed up the production process (Sandulli et al. 2012), but it seems that considerable (labor) resources in these firms are also spent on maintaining this infrastructure, countervailing any productivity gains in the core business.

We give an intuition for the high markups of micro-sized firms in Section 4.2.

Prices for the lump sum fees had not been adjusted since 2004 (legal services), 2009 (architecture and engineering), and 1998 (tax consulting).

References

Ackerberg, D. A., Caves, K., & Frazer, G. (2015). Identification properties of recent production function estimators. Econometrica, 83(6), 2411–2451.

Ahmad, N., Ribarsky, J., and Reinsdorf, M. (2017). Can potential mismeasurement of the digital economy explain the post-crisis slowdown in GDP and productivity growth? OECD Statistics Working Papers. No. 2017/09.

Alon, T., Berger, D., Dent, R., & Pugsley, B. (2018). Older and slower: The startup deficit’s lasting effects on aggregate productivity growth. Journal of Monetary Economics, 93(1), 68–85.

Andrews, D., Criscuolo, C., and Gal, P. (2015). Frontier firms, technology diffusion and public policy: Micro evidence from OECD countries. OECD Productivity working papers No. 2.

Andrews, D., Criscuolo, C., and Gal, P. (2016). The best versus the rest: The global productivity slowdown, divergence across firms and the role of public policy. OECD Productivity working papers No. 5.

Andrews, D., Criscuolo, C., and Gal, P. (2019). The best versus the rest: Divergence across firms during the global productivity slowdown. CEP Discussion Paper 1645.

Audretsch, D., Kritikos, A. S., & Schiersch, A. (2020). Microfirms and innovation in the service sector. Small Business Economics, 55(4), 997–1018.

Aw, B. Y., Roberts, M. J., & Xu, D. Y. (2011). R&D investment, exporting, and productivity dynamics. American Economic Review, 101(4), 1312–44.

Backus, M. (2020). Why is productivity correlated with competition? Econometrica, 88(6), 2415–2444.

Bijens, G., & Konings, J. (2018). Declining business dynamism in Belgium. Small Business Economics, 54(4), 1201–1239.

Black, S., & Lynch, L. (1996). Human-capital investments and productivity. American Economic Review, 86(2), 263–267.

Black, S., & Lynch, L. (2001). How to compete: The impact of workplace practices and information technology on productivity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(3), 434–445.

Bloom, N., Jones, C., Van Reenen, J., & Webb, M. (2020). Are ideas getting harder to find? American Economic Review, 110(4), 1104–1144.

Boothby, D., Dufour, A., & Tang, J. (2010). Technology adoption, training and productive performance. Research Policy, 39(5), 650–661.

Bosma, N., van Praag, M., Thurik, R., & de Wit, G. (2004). The value of human and social capital investments for the business performance of startups. Small Business Economics, 23(3), 227–246.

Byrne, D. M., Fernald, J. G., and Reinsdorf, M. B. (2016). Does the United States have a productivity slowdown or a measurement problem? Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper 2016-03.

Cirillo, V., Fanti, L., Mina, A., and Ricci, A. (2021). Digitalizing firms: Skills, work organization and the adoption of new enabling technologies. LEM Working Paper Series, 4.

Collard-Wexler, A., & De Loecker, J. (2015). Reallocation and technology: Evidence from the US steel industry. American Economic Review, 105(1), 131–171.

Collard-Wexler, A. and Loecker, J. D. (2016). Production function estimation with measurement error in inputs. NBER Working Paper No. 22437.

De Loecker, J. (2011). Product differentiation, multiproduct firms, and estimating the impact of trade liberalization on productivity. Econometrica, 79(5), 1407–1451.

De Loecker, J. (2011). Recovering markups from production data. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 29(3), 350–355.

De Loecker, J., Eeckhout, J., & Unger, G. (2020). The rise of market power and the macroeconomic implications. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 561–644.

De Loecker, J., Goldberg, P. K., Khandelwal, A. K., & Pavcnik, N. (2016). Prices, markups, and trade reform. Econometrica, 84(2), 445–510.

De Loecker, J. and Scott, P. T. (2016). Estimating market power: Evidence from the US brewing industry. NBER Working Paper Series, 22957.

De Loecker, J., & Warzynski, F. (2012). Markups and firm-level export status. American Economics Review, 102(6), 2437–2471.

Decker, R., Haltwanger, J., Jarmin, R., & Miranda, J. (2016). Declining business dynamism: What we know and the way forward. American Economic Review, 106(5), 203–207.

Destatis (2020a). Input-output table \(2016\). GENESIS 81511-0004, Federal Statistical Office.

Destatis (2020b). National accounts, domestic product 2019. Fachserie, 18, 1.1.

Destatis (2020c). Producer price index for services: Germany, years, sector. GENESIS 61311-0003, Federal Statistical Office.

Destatis (2021a). Employment. Part-time/Full-time workers: 1985-2019. GENESIS 12211-0011, Federal Statistical Office.

Destatis (2021b). Statistics on employees with social securitity contributions: 2008-2020. GENESIS 13111-0004, Federal Statistical Office.

Dierks, S., Schiersch, A., & Stede, J. (2019). Industry conversion tables for German firm-level data. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik, 240(5), 677–690.

Doraszelski, U., & Jaumandreu, J. (2013). R&D and productivity: Estimating endogenous productivity. Review of Economic Studies, 80(4), 1338–1383.

Duernecker, G., Herrendorf, B., & Ákos Valentinyi (2016). Unbalanced growth slowdown. Mimeo.

Dulleck, U., & Kerschbamer, R. (2006). On doctors, mechanics, and computer specialists: The economics of credence goods. Journal of Economic Literature, 44(1), 5–42.

EC (2015). Fixed tariffs for architects and engineers. Infringement Procedure against Germany 2015(2057), European Commission.

EC (2018a). First batch of non-conformity checks of the professional qualifications directive 2005/36/EC as revised by directive 2013/55/EU Infringement Procedure against Germany 2018(2171), European Commission.

EC (2018b). Possible violation of articles 6-8 of the Services Directive - points of single contact. Infringement Procedure against Germany 2018(2376), European Commission.

EC (2018c). Second batch of non-conformity checks of the professional qualifications directive 2005/36/EC as revised by directive 2013/55/EU. Infringement Procedure against Germany 2018(2291), European Commission.

Emons, W. (1996). Credence goods and fraudulent experts. RAND Journal of Economics, 28(1), 107–119.

Eurostat (2008). NACE Rev. 2: Statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community. Eurostat Methologies and Working Papers, KS-RA-07-015-EN-N.

Flegler, P. and Krämer, H. (2021). Das Produktivitätsparadoxon der unternehmensbezogenen Dienstleistungen. ifo Schnelldienst, 74:38–45

Foster, L., Haltiwanger, J., & Syverson, C. (2008). Reallocation, firm turnover, and efficiency: Selection on productivity or profitability? American Economic Review, 98(1), 394–425.

Ganglmair, B., Hahn, N., Hellwig, M., Kann, A., Peters, B., & Tsanko, I. (2020). Price markups, innovation, and productivity: Evidence from Germany. Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh: Research report.

Gordon, R. J. (2012). Is U.S. economic growth over? Flatering innovation confronts the six headwinds. NBER Working Paper No. 18315.

Grieco, P. L., Li, S., & Zhang, H. (2016). Production function estimation with unobserved input price dispersion. International Economic Review, 57(2), 665–690.

Gropp, R., Ongena, S., Rocholl, J., & Saadi, V. (2020). Are US industries becoming more concentrated? IWH Discussion Papers No. 12/2020.

Grullon, G., Larkin, Y., & Michaely, R. (2019). Are US industries becoming more concentrated? Review of Finance, 23(4), 697–743.

Hall, R. E. (1988). The relation between price and marginal cost in U.S. industry. Journal of Political Economy, 96(5), 921–947.

Hartwig, J., & Krämer, H. (2019). The growth disease at 50 – Baumol after Oulton. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 51(C), 463–471.

Hsieh, C.-T. , & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2019). The industrial revolution in services. NBER Working Paper, 25968.

Katayama, H., Lu, S., & Tybout, R. J. (2009). Firm-level productivity studies: Illusions and a solution. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 27(3), 403–413.

Klette, T. J., & Griliches, Z. (1996). The inconsistency of common scale estimators when output prices are unobserved and endogenous. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11(4), 343–361.

Levinsohn, J., & Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Review of Economic Studies, 70(2), 317–341.

Malerba, F., & Orsenigo, L. (2015). The evolution of the pharmaceutical industry. Business History, 57(5), 664–687.

McGowan, M. A., Andrews, D., & Millot, V. (2017). The walking dead? Zombie firms and productivity performance in oecd countries. OECD Working Papers No. 1372.

Medrano-Adán, L., Salas-Fumás, V., & Sanchez-Asin, J. J. (2019). Firm size and productivity from occupational choices. Small Business Economics, 53, 243–267.

Mimra, W., Rasch, A., & Waibel, C. (2016). Price competition and reputation in credence goods markets: Experimental evidence. Games and Economic Behavior, 100(6), 337–352.

Moral-Benito, E. (2018). Growing by learning: Firm-level evidence on the size-productivity nexus. SERIEs, 9, 65–90.

Mundlak, Y., & Hoch, I. (1965). Consequences of alternative specifications in estimation of Cobb-Douglas production functions. Econometrica, 33(4), 814–828.

Nordhaus, W. D. (2021). Are we approaching an economic singularity? Information technology and the future of economic growth. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 13(1), 299–332.

Olley, S., & Pakes, A. (1996). The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica, 64(6), 1263–1297.

Oulton, N. (2001). Must the growth rate decline? Baumol’s unbalanced growth revisited. Oxford Economic Papers, 53(4), 605–627.

Oulton, N. (2013). Has the growth of real gdp in the uk been overstated because of mismeasurement of banking output? National Institute Economic Review, 224(1), R59–R65.

Owalla, B., Gherhes, C., Vorley, T., & Brooks, C. (2021). Mapping SME productivity research: A systematic review of empirical evidence and future research agenda. Small Business Economics, online first.

Parrotta, P., Pozzoli, D., & Pytlikova, M. (2014). Labor diversity and firm productivity. European Economic R, 66(C), 144–179.

Peters, B., Roberts, M., Vuong, V., & Fryges, H. (2017). Estimating dynamic R&D choice: An analysis of costs and long-run benefits. RAND Journal of Economics, 48(2), 409–437.

Runst, P., & Thomä, J. (2021). Does personality matter? Small business owners and modes of innovation: Small Business Economics, online first.

Sandulli, F., Fernández-Menéndez, J., Rodríguez-Duarte, A., & López-Sánchez, J. (2012). The productivity payoff of information technology in multimarket SMEs. Small Business Economics, 39(1), 99–117.

Siachou, E., Vrontis, D., & Trichina, E. (2021). Can traditional organizations be digitally transformed by themselves? The moderating role of absorptive capacity and strategic interdependence. Journal of Business Research, 124(1), 408–421.

Syverson, C. (2017). Challenges to mismeasurement explanations for the US productivity slowdown. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 165–186.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). On estimating firm-level production functions using proxy variables to control for unobservables. Economics Letters, 104(3), 112–114.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tomaso Duso, Pio Baake, two anonymous referees, the participants of the IO Brown Bag Seminar at DIW Berlin and of the INNOMSME workshop in Athens for helpful comments and suggestions. Special thanks to the team at the Federal Statistical Office Berlin-Brandenburg.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work received funding from the research grant “INNOMSME” (project number: 01UI1802), provided by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A. Definition of business services

In this appendix, we briefly describe which economic activities are summarized under business services and why the study focuses on professional services. Business services, or MtN, is used by German Statistical Offices for the sum of two NACE sections: professional, scientific, and technical activities (section M) — we use the shorted name professional services — as well as administrative and support activities (section N), which we call administrative services. They comprise a variety of professions; including, for instance, lawyers, consultancy, advertiser, leasing activities, and travel agencies (see Table 3).

The productivity decline is not confined to professional services, but is more broadly found among all business services (MtN, see Fig. 14 in Appendix D). However, administrative services (NACE N) contain employment placement and temporary employment agencies (division N78). This may bias the labor productivity measures, because the tremendous growth in temporary agency work over the last decades is not related to internal employment in this division since temporary agency workers usually work in other industries. In order to avoid such bias, we focus on professional services (NACE M) in our analysis.

Appendix B. Markup estimation

1.1 B.1 Calculation of the price margins over marginal costs

We closely follow De Loecker et al. (2020) and use firm-level production data to estimate markups, i.e., price margins over marginal costs. The strategy was initially proposed by De Loecker (2011b) and De Loecker and Warzynski (2012) and, unlike previous approaches, does not require any assumptions on a specific demand system. This is particularly useful for estimating markups in professional services, as markets in this industry are highly intransparent and factors other than prices (e.g., reputation) play an important role for determining consumer choices.

We assume that firms decide on the optimal size of their labor force in a cost minimization problem, which can be expressed by the following Lagrangian function

where \(r_t\) denote the user costs of capital varying with year t, \(K_{it}\) is firm i’s capital stock, \(L_{it}\) is the number of employees who each receive an average firm-level wage \(w_{it}\), \(p_M M_{it}\) denotes the expenditure for intermediate goods and services, and \(Q_{it}\) is the output that the firm produces per year. If \(Q(\cdot )\) is continuous and twice differentiable, the first-order condition with respect to labor is given by

where \(\lambda _{it}\) are the marginal costs of production at a given level of output. Furthermore, the formal definition of the output elasticity of labor is given by

Using Eqs. 5 and 6, we can calculate firm-specific markups \(\mu ^l_{it}\), i.e., the price margin over marginal costs, as

Since the true output is usually not observed in the data, we correct the markup formula for the log measurement error \(\epsilon _{it}\) and obtain the following estimate for the firm-level markup

1.2 B.2 Production function estimation

The calculation of the markups requires an estimate of the output measurement error and of the output elasticity of labor. We assume a production function with three inputs, capital \(K_{it}\), labor \(L_{it}\), and intermediate goods and services \(M_{it}\), used to produce the gross production value \(S_{it}=P_{it}Q_{it}\). The observed output can differ from the true output by some measurement error \(\epsilon _{it}\) and production depends on unobservable total factor productivity \(\Omega _{it}\). Both labor and intermediate goods and services are flexible, static inputs that can be adjusted within one year with negligible adjustment costs. Ackerberg et al. (2015), Levinsohn and Petrin (2003), and Doraszelski and Jaumandreu (2013) stress that output elasticities are difficult to identify in the presence of more than one flexible input. Therefore, we follow De Loecker et al. (2020), De Loecker and Scott (2016) and Ganglmair et al. (2020) by assuming a Leontief production function given by

that is estimated separately within each NACE 2-digit industry. The true functional form of \(f(\cdot )\) is approximated by a translog function with

where lower-case letters denote logs, \(\tau _{r}\) are region fixed effects, and \(\eta _{b}\) controls for the firm’s legal form. We apply the control function approach of Ackerberg et al. (2015), which was initially proposed by Olley and Pakes (1996) to estimate the output elasticity of labor. The identification strategy exploits the fact that current shocks to productivity will immediately affect firms’ demand of a fully flexible, static input, but not those of dynamic inputs, which react more slowly to productivity shocks, given the adjustment costs. The inverted input demand function of a static, flexible input can then be used to express productivity in terms of observables. We use the input demand for intermediate goods and services to express productivity as

and replace productivity in Eq. 10 with Eq. 11. Furthermore, we assume that productivity follows a first-order Markov process with

The production function is estimated in a two-step GMM procedure, where the output elasticities are identified from the moment conditions \(\mathbb {E}[l_{it-1},k_{it}|v_{it}]=0\). Applying the approach of Ackerberg et al. (2015), we consider the possibility that total factor productivity correlates with input choice, a well-known simultaneity problem that otherwise leads to biased estimates of the output elasticities Mundlak and Hoch (1965); Levinsohn and Petrin (2003); Olley and Pakes (1996); Wooldridge (2009). The control function approach is widely applied to determine total factor productivity in various industries and to obtain unbiased estimates for the output elasticities (e.g., De Loecker et al. (2020); Peters et al. (2017); De Loecker et al. (2016); Collard-Wexler and De Loecker (2015); Doraszelski and Jaumandreu (2013); Parrotta et al. (2014); De Loecker (2011a); Aw et al. (2011)). Finally, De Loecker et al. (2020) and De Loecker and Scott (2016) stress that the estimate for the markup in Eq. 8 is incomplete under a Leontief production technology. In this case, \(\lambda _{it}=\lambda ^l_{it}+\lambda ^m_{it}\) holds, since both conditions of the Leontief function have to be met simultaneously, which requires taking the first-order condition of Eq. 4 for both parts of \(Q(\cdot )\). The price margin over marginal costs is then defined as

The second component \(\lambda ^m_{it}\) of the marginal costs can be derived from the first-order condition with respect to the intermediate input and is equal to \(p_M/\theta ^M_{it}\). The output elasticity for the intermediate input is easily computed by rearranging \(Q_{it}=\theta ^M_{it}M_{it}\). Inserting both in the equation above yields

Using the definition of the gross production value \(S_{it}=P_{it}Q_{it}\) and correcting for the output measurement error, we obtain the final markup estimate

Appendix C. Tables

Appendix D. Figures

Employment and value added growth in German industries since 1995. Source: Destatis (2020b)

Average expenditure for intermediate goods and services per employee. Source: Destatis (2020b)

Labor productivity growth in German professional services since 1995. Source: Destatis (2020b)

Labor productivity growth in the German business economy since 1995. Source: Destatis (2020b)

Labor productivity growth based on sales in the German economy since 1995. Source: Destatis (2020b)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kritikos, A.S., Schiersch, A. & Stiel, C. The productivity shock in business services. Small Bus Econ 59, 1273–1299 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00625-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00625-6