Abstract

We examine the moderating role of being a supervisor for meaning and autonomy of self-employed and employed workers. We rely on regression analysis applied after entropy balancing based on a nationally representative dataset of over 80,000 individuals in 30 European countries for 2005, 2010, and 2015. We find that being a self-employed supervisor is correlated with more work meaningfulness and autonomy compared with being a salaried supervisor working for an employer. Wage supervisors and self-employed supervisors experience similar stress levels and have similar earnings, though self-employed supervisors work longer hours. Moreover, solo entrepreneurs experience slightly less work meaningfulness, but more autonomy compared with self-employed supervisors. This may be explained by the fact that solo entrepreneurs earn less but have less stress and shorter working hours than self-employed supervisors.

Plain English Summary

Simplified summary and main conclusions. Being your own boss provides more work autonomy and meaning than working for an employer. However, the extent to which self-employed and employed people experience more autonomy and work meaningfulness depends on whether they supervise others or not. Solo entrepreneurs tend to have slightly more autonomy but less work meaningfulness than self-employed supervisors. Salaried employees with managerial duties experience higher levels of both work meaningfulness and autonomy compared with colleagues without such duties, meanwhile. Thus, the principal implication of this study is that the well-being benefits of self-employment depend on whether self-employed and employed people manage others.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Despite long working hours, low incomes, uncertainty, and high levels of stress, self-employment is widely considered to be one of the most desirable occupations. Over a third of all Europeans, for example, aspire to work for themselves (European Commission, 2013). But why do so many people dream of becoming their own boss even if objectively they may end up with more stressful and challenging working conditions?

One possible explanation for this “puzzling” observation is that self-employment, as a self-directed activity, provides more autonomy and control over one’s work. In turn, higher levels of autonomy can lead to the fulfillment of other basic psychological needs such as competence and relatedness that can further improve one’s sense of well-being and vitality (Nikolaev et al., 2020; Shir et al., 2019; Stephan et al., 2020).Footnote 1 Indeed, survey evidence reveals that one of the most common motivations for starting a business, especially in advanced economies, is to gain more freedom by escaping the drudgery of working for others (European Commission, 2013). Therefore, understanding how self-employment contributes to individual fulfillment and well-being is of “utmost importance” to business scholars (Wiklund et al., 2019, p. 579; Boudreaux et al., 2021).

More recently, entrepreneurship scholars have started studying essential boundary conditions of the relationship between self-employment and well-being. For example, self-employed people who are pushed into entrepreneurship due to a lack of alternatives (i.e., “necessity entrepreneurs”) are less likely than those who start a business to capture opportunities (i.e., “opportunity entrepreneurs”) to experience high levels of job satisfaction and autonomy (Stephan, 2018). However, we still lack sufficient evidence regarding other important job characteristics, such as whether one’s job requires managing others, that can explain well-being differences between the self-employed and employed (Burke & Cowling, 2020a). Moreover, despite the ample evidence that self-employment promotes job satisfaction, other well-being outcomes are less well-understood in the context of entrepreneurship. In this regard, several recent papers have called for more research on the effect of self-employment on eudaimonic aspects of well-being such as work meaningfulness (Ryff, 2019; Stephan, 2018; Wiklund et al., 2019).Footnote 2

Our study contributes to this line of research by examining to what extent the benefits of self-employment in terms of work autonomy and meaningfulness depend on whether people employ and manage others. We specifically focus on two dimensions of perceived well-being—work meaningfulness and autonomy—that have not received much attention in the literature on self-employment and well-being. Work meaningfulness reflects activities that individuals view as purposeful and worthwhile and bring external appreciation and fulfillment (Rosso et al., 2010). As a self-directed and emotional journey, characterized by a deep sense of purpose, self-employment can lead to higher levels of work meaningfulness (Nikolova & Cnossen, 2020; Stephan et al., 2020). Meaningful work is important because it predicts outcomes such as absenteeism, quit intentions, and organizational commitment (Nikolova & Cnossen, 2020; Rosso et al., 2010; Steger et al., 2012). Moreover, it is an intrinsically valuable aspect of people’s work lives (Ryff, 2017) and critical to job crafting and understanding the benefits of different career choices.

We also focus on the implications of supervising others for work autonomy. Having autonomy entails that work outcomes depend on workers’ own initiative and effort rather than superiors or procedures (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). As such, working conditions allowing for self-direction, self-organization, and independence contribute to one’s sense of work autonomy.

Understanding whether the well-being benefits of self-employment depend on supervising others is important because the vast majority of small businesses tend to be sole proprietorships that rarely grow beyond a single employee—the original owner (e.g., Parker, 2009).Footnote 3 Recent research has pointed out that solo entrepreneurs such as freelancers play a critical role in providing a specialist expertise and knowledge to firms by allowing them to adopt more flexible and agile business models that can help them respond to a dynamically changing business environment (e.g., Burke & Cowling, 2020a). However, while research has already started exploring the effect of solo entrepreneurship on job creation, innovation, and various firm-level outcomes (e.g., Burke & Cowling, 2020b, c), far less is known about non-monetary outcomes associated with running a business solo.

Using nationally representative data of over 80,000 individuals in 30 European countries for 2005, 2010, and 2015, this paper shows that being self-employed is associated with more meaningfulness and autonomy, but supervising others moderates the relationship. Self-employed supervisors have higher levels of work meaningfulness and autonomy compared with managers who are not self-employed. At the same time, contrary to previous studies (e.g., Prottas & Thompson, 2006), we find that the solo self-employed derive the highest levels of autonomy relative to any other worker group. This finding corroborates recent work underscoring the heterogeneity among the self-employed and the solo self-employed (e.g., Burke & Cowling, 2020a, b; Pantea, 2020; van Stel & van der Zwan, 2020), but also highlights that there could be important regional differences that future research can explore.

Overall, our results suggest that the solo self-employed experience high levels of autonomy and meaning. Our finding may indirectly explain the trends documented in the literature that an increasing number of people are choosing to become solo self-employed (Burke & Cowling, 2020a, c; Shane, 2008). Understanding if, when, and why managing others brings autonomy and work meaningfulness is also critical for developing work practices that increase work motivation and worker well-being, which are key to organizational success. However, more research is needed to show the causal nature of these relationships.

2 Self-employment, work meaningfulness, and work autonomy

Meaningful work perceptions reflect the degree to which people believe that what they do at work has personal significance, contributes to finding meaning in life, facilitates personal growth, and positively impacts the greater good (Lepisto & Pratt, 2017; Martela & Riekki, 2018; Steger et al., 2012). Studies find that those who engage in entrepreneurship—a self-directed process that is more deeply aligned with a person’s intrinsic values, needs, skills, and interests—are more likely to derive meaning from their jobs than other workers (Nikolova & Cnossen, 2020; Stephan et al., 2020). This is because self-employment starts with the choice to do what one considers worth doing. Many entrepreneurs are deeply passionate about their ventures beyond the mere financial gain (Cardon et al., 2012). Forming such profound identity connections is a manifestation of the personal significance most self-employed people derive from their work as they pour time, energy, and passion into developing their ventures.

Work autonomy refers to the degree to which a “job provides substantial freedom, independence, and discretion to the individual in scheduling work and determining the procedures to be used in carrying it out” (Hackman & Oldham, 1976, p. 258). The self-employed enjoy a higher degree of work autonomy and control compared to employees because they have more freedom when choosing the substance of their work, how to complete various work tasks, and, ultimately, why they want to pursue a particular course of action (e.g., Nikolaev et al., 2020; Stephan, 2018).Footnote 4 This makes them more likely to design their work to be consistent with their strengths, values, needs, and competencies, leading to greater person-environment fit (Baron, 2010). In turn, the self-employed are more likely than wage employees to pursue activities that allow them to express their identity in an authentic way, one that is consistent with their purpose and long-term goals (Baron, 2010).

3 Supervising others, work autonomy, and meaning

We expect supervisors to derive a greater level of autonomy and meaning relative to those who do not manage others. This might be because managing others brings a sense of self-efficacy and empowerment or because managers receive more timely and accurate information and have more opportunities to participate in decision-making (Johnson, 2000). Supervisors may also receive more recognition for their work because their role within the organization is more visible than that of other employees (Johnson, 2000). In addition, an essential feature of being a manager is motivating employees, which requires clearly communicating why one’s job matters, how it fits within the bigger picture and can help the company achieve its mission. Supervisors may also derive more meaning from their jobs by coaching and advising subordinates, which can leave them with a greater sense of relatedness because they have a more visible impact on the well-being of others.

4 Meaning and autonomy at work: the moderating role of managing others

While the self-employed derive greater autonomy and meaning from their work than salaried employees, we argue that supervising others can be a vital job feature that moderates this relationship. Specifically, it is unclear whether managers working for an employer and solo entrepreneurs derive similar well-being benefits relative to self-employed people who employ and supervise others. These questions are highly relevant for individuals who consider (solo) self-employment careers.

Self-employed people who have employees (i.e., subordinates) tend to be more optimistic and growth-oriented business owners who are driven by a mission and a sense of purpose (Dellot, 2014). In turn, future growth aspirations and a sense of long-term purpose can be particularly impactful for an entrepreneur’s sense of achievement, personal growth, autonomy, and meaning (Nikolaev et al., 2020; Wiklund et al., 2003). Entrepreneurs who employ others are also more likely to perceive that they have lower workloads, more time to spend on favored tasks, and greater control over their company and future than solo entrepreneurs (Wiklund et al., 2003). This is because they can delegate more repetitive and less mentally stimulating tasks to their employees. For example, instead of inputting transactions in the books, they can spend their time analyzing and forecasting trends that can determine the company’s future direction. While wage-employed supervisors can also delegate tasks to others, they are often constrained by the nature of their more specialized positions. For example, various organizational rules, practices, and procedures may restrict the extent to which they can hire new employees, alleviate their own workloads, spend more time on favorable tasks, and, more generally, have input on the company’s mission and future.

H1. Self-employed supervisors experience greater work autonomy and meaning relative to wage-employed supervisors.

The research on whether solo entrepreneurship is associated with autonomy compared with supervisor self-employment is relatively scarce. In one study from the USA, Prottas and Thompson (2006) find that business owners who supervise and employ others have slightly higher autonomy levels than solo entrepreneurs, but they also have more job pressure. On the other hand, having employees increases job demands and stress (Hessels et al., 2017), thus constraining the autonomy and the ability to derive work meaningfulness compared to the solo self-employed.

While some solo entrepreneurs can be freedom-loving or driven by the opportunity to showcase their creative talents (Burke & Cowling, 2020a), others tend to be survivors who are struggling to make ends meet, in part due to the competitive markets in which they operate (Dellot, 2014). The solo self-employed may also experience more uncertainty, job insecurity, and income volatility than the self-employed who employ others. They are also more likely to work extended work hours, face intense time-pressures, and perceive various role-ambiguities since they lack the option to delegate responsibilities to others (Parker, 2018). Because solo entrepreneurs have no supervisors and colleagues, they may lack social support (Gumpert & Boyd, 1984; Stephan, 2018). As such, solo entrepreneurs may experience less autonomy and control over their work schedules relative to those who supervise others (both self-employed and employed supervisors). Thus, we hypothesize that:

H2: Solo-entrepreneurs experience less work autonomy and meaning compared to self-employed supervisors.

5 Methods

5.1 Data and analysis sample

We test our hypotheses using pooled cross-sectional data from the European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS) for 2005, 2010, and 2015 for over 80,000 individuals living in 30 European countries. We obtained the data from the UK Data Service (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2007; 2012; 2017; 2019). This rich dataset contains worker-level information on work meaningfulness, self-employment, and personal and job characteristics, including supervising others.

The analysis sample focuses on respondents from countries polled in all three waves, i.e., the current 27 European Union Member States, the UK, Turkey, and Norway. Holding the country composition constant over time increases the comparability of the results. Each country sample contains about 1000 individuals, though certain countries are oversampled in particular years. Table A1 details the number of observations per country, year, and self-employment status in the final analysis sample.

We restrict the analysis sample to individuals with one employer to avoid spillovers of work meaningfulness and autonomy across different jobs. Furthermore, we exclude those reporting to be self-employed and simultaneously working in the public sector. Due to a low number of observations, we exclude workers in joint private–public organizations, those in nonprofit sectors, and “other” sectors. Since the armed forces sector is primarily public and has only a few observations, we also drop this sector. We restrict the analysis sample to the set of observations with non-missing information on work meaningfulness, autonomy, self-employment, and supervisor status, i.e., the critical variables in this analysis (Table 1 and Table A1). For all other variables, to prevent loss of information, we include all observations, including the missing ones, as explained below.

5.2 Variables

5.2.1 Dependent variables

Our dependent variables are work meaningfulness and autonomy, both of which are composite indices created using polychoric principal component analysis, which is a data reduction procedure incorporating the ordered scale of the underlying items (Olsson, 1979). We scale both indices to range between 0 and 100 and, for ease of interpretation, standardize them to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. The information in Table 1 details the creation of these indices.

First, following the literature (Nikolova & Cnossen, 2020; Stephan et al., 2020), we create work meaningfulness based on two items in the EWCS (“You have the feeling of doing useful work” and “Your job gives you the feeling of work well done”), which are both measured on a scale ranging from 1 (always) to 5 (never). We reversed the range from 1 (never) to 5 (always) so that higher values on the original scale indicate greater meaningfulness perceptions. The two items have a correlation of 0.6, which is moderately high. The scale reliability coefficient, Cronbach’s α, is 0.75, meanwhile, indicating the appropriateness of combining these variables into an index. Stephan et al. (2020) demonstrate that a meaningful work index based on these items highly correlates with other known scales in the literature, including Steger’s Work as Meaning Inventory (WAMI), which is the most well-known in the literature.Footnote 5

Second, like in Stephan et al. (2020), we measure autonomy as a multi-dimensional index combining (1) ability to choose or change the order of tasks, (2) ability to select or change methods of work, and (3) ability to choose or change speed or rate of work (Cronbach’s α = 0.78). These variables capture task autonomy, i.e., the ability to control and self-organize the working process.

5.2.2 Key independent variable and moderator

Our key independent variable, “self-employed,” distinguishes between those owning their own business and a comparison of “salaried workers,” i.e., wage employees in the private and public sectors. The self-employed are those who own their own business or work as freelancers and may be working alone or employ others.Footnote 6, Footnote 7 The survey unfortunately does not distinguish between incorporated and unincorporated businesses.Footnote 8

Furthermore, supervisor status, which is a binary indicator for whether the respondent manages other people or not, is both a key independent variable and a moderator. In separate regressions, we also consider the number of people the respondent supervises. Because the distribution of this variable is very right-skewed (skewness = 54.5, kurtosis = 4335.5), we take its natural logarithm. While the binary supervisor status captures the consequences of holding a managerial position at the extensive margin, the (natural log of the) number of people supervised captures the intensive margin of supervisory status.

5.2.3 Control variables

Following other papers in the literature based on the EWCS (e.g., Aleksynska, 2018; Nikolova & Cnossen, 2020), the control variables include standard job characteristics such as income, working hours, tenure (number of years in the current position), job advancement opportunities, and job insecurity, as well as socio-demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and marital status (Table 1). These variables correlate with the probability of being self-employed/supervisor and work meaningfulness and autonomy. In addition to these controls, we include year-, country-, and industry-fixed effects, and interview controls—duration (in minutes), number of people present during the interview, interview month, and interview day—to account for their influence on survey answers. These fixed effects and controls help adjust for unobserved confounders that might otherwise be related to labor market status, meaning, and autonomy.

To avoid bias from dropping observations with missing information, for all control variables, we include the missing observations in the regressions by creating an additional category denoting no answer/refusals/do not know answers. For example, the variable male is coded as 1 if the respondent is female, 2 if the respondent is male, and 3 if there is missing information regarding the respondent’s gender. We form separate dummy variables for males, females and those with missing information on gender, with males as the reference. We transform continuous variables into categorical ones, and we include an additional category to denote the missing information (see Table 1). Finally, for all categorical variables, the first category is always the reference (omitted) category in the analyses.

5.3 Econometric model

To test our hypotheses, we estimate the following regression model using ordinary least squares (OLS) with entropy balancing weights. In alternative specifications, we also apply Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM) weights. Specifically, for each individual i in period t, working in industry j, and living in country c is

where DV is our dependent variable (work meaningfulness or autonomy); SELF denotes our measure of self-employment; SV denotes our supervisor measure; \(SELF\times SV\) is an interaction between the self-employment and supervisor status variables; X is a vector of control variables (income, education, household size, working hours, tenure, job advancement opportunities, job insecurity, age, gender, marital status, and the number of children). Our regression models either include a dummy indicator for supervisor status or the natural log of the number of employees supervised. Moreover, \({\beta }_{1}\), \({\beta }_{2}\), and \({\beta }_{3}\) are the parameters of interest and \(\gamma\) denotes a vector of parameters for the control variables; \(\mu\), \(\lambda\), and δ, denote country, industry, and year fixed effects, respectively. \({\varepsilon }_{it}\) is our stochastic error term, and the subscripts i, c, t, and j relate to the individual, country, time, and industry, respectively.

The main empirical challenge to identifying the causal effects of self-employment and supervisor status on work meaningfulness and autonomy is self-selection. We have two potentially endogenous variables (self-employment and supervisory status), which poses a further complication. Specifically, individuals with certain unobservable characteristics or preferences may be more likely to become self-employed or supervisors. For example, individuals who value work meaningfulness and autonomy or have a high entrepreneurial aptitude may be more likely to start their own business. Similarly, those who do not like taking responsibility and managing others may choose to work as subordinates rather than managers.

Ideally, we would have liked to rely on a randomized control trial eliminating such selection issues, whereby self-employment and supervisor status are randomly allocated. However, such a study is not feasible. An alternative would be to find instruments for self-employment and supervisor status, which would predict both of these variables while being uncorrelated with the error term of Eq. (1) above. Admittedly, finding such a set of instruments is non-trivial. Given these methodological issues, providing a causal estimate of the true consequences of self-employment and being a supervisor is challenging. Nevertheless, to the extent possible, we attempt to deal with selection issues by relying on an OLS regression using entropy balancing weights. While we have two endogenous variables, the method only allows us to deal with selection for one of them, and we focus on self-employment.

Specifically, in a first step, we rely on a non-parametric matching procedure called entropy balancing (Hainmueller, 2012). This preparatory step creates comparable groups of statistically identical individuals based on their observable characteristics, except that one individual is self-employed and the other is not. The second step involves estimating a weighted regression of self-employment and being a supervisor on work meaningfulness and autonomy using the entropy balancing weights. Admittedly, this procedure eliminates issues related to selection on observables, but not necessarily selection on unobservables. Like other matching techniques, with entropy balancing, we have to assume that the selection on unobservables is correlated with the selection on observables.

The entropy balancing method is arguably more econometrically and practically advantageous compared with standard propensity score and other matching methods. The main advantages include efficiency, improved covariate balance, and removing the need to tinker with the tolerance levels and the choice of the covariates (Hainmueller, 2012). First, entropy balancing allows for matching on both moments of the covariate distribution, both the mean and the variance, which is more precise and superior to matching only on the mean as most other matching methods do. Second, the entropy balancing does not drop observations without exact matches, which allows us to keep the sample composition between OLS estimations and the entropy balancing constant and makes the results directly comparable. Third, the generated weights allow achieving balance in terms of the mean and variance of the covariate distribution of both the treated (self-employed) and comparison (salaried employee) groups. Fourth, the entropy balancing takes into account all covariates, while other matching techniques require picking and choosing matching covariates, which is based on researcher discretion and introduces bias.

To calculate the entropy balancing weights, we rely on Stata’s ebalance user-written package (Hainmueller & Xu, 2013). We ensure that the treated and comparison groups are statistically identical along all control variables based on their means and variances. The balancing test results are available in Appendix Table A3.

In robustness checks, we compare our results with simple OLS regressions (Table A4) and weighted OLS regressions using another technique, Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM) (Table 4). Unlike propensity score matching (PSM), the advantage of CEM is that CEM does not estimate the probability of being treated. This method is also advantageous when there are continuous matching covariates or covariates with a lot of categories (Greifer & Stuart, 2021). Instead, it coarsens the covariates in strata and assigns weights to individuals depending on how close they are to the treated group (Gustafsson et al., 2016; Iacus et al., 2009, 2012; King & Nielsen, 2019). As with the entropy balancing, these matching weights are particularly useful as they can be included in subsequent regression analyses.Footnote 9 The main reasons why we did not select the CEM as the main method for the analysis are that it involves researcher discretion in choosing the matching covariates and that it drops observations for which no match is found (Greifer & Stuart, 2021). Our CEM estimations use a matched sample with a total of 58,001 observations, matching on select covariates—age, gender, education, household size, marital status, and number of children. We ensure that the treated and comparison groups are statistically identical along all control variables based on their means. The balancing test results are available in Table A5 in the Appendix, and the matching diagnostics indicate a successful match, as reported by the decreased L1 statistic in Table A6 (as compared to Table A5).

6 Results

6.1 Descriptive statistics

The self-employed have higher work meaningfulness and autonomy perceptions than their wage counterparts (Table 2). Specifically, the mean work meaningfulness for the self-employed is 52.6 (median = 58.7), compared with an average value of 49.5 for salaried (i.e., wage) employees (median = 52.7). Similarly, the self-employed enjoy higher levels of autonomy compared with wage employees. The mean (median) level of autonomy perceptions for the self-employed is 57.1 (58.8) compared with 48.7 (51.3) for wage employees.

Furthermore, Table 2 provides information about the differences in the individual and job characteristics between the self- and wage-employed. In addition to having more autonomy and meaning, business owners are also more likely to be supervisors (30%) compared to wage employees (14%). Among supervisors, the average number of people supervised is 12.6 employees. For the self-employed, it is 6, and for the non-self-employed, it is 15.2 (not shown in Table 2). At the same time, the average number of workers supervised is slightly lower for the self-employed (1.8) compared with 2.1 for wage employees.

Table 2 further details that the self-employed also work longer hours, are more likely to be older, high-income, male, and are less likely to have tertiary education than private and public sector employees. Table 2 demonstrates that business owners differ from wage employees along several dimensions, which is why our empirical analyses take into account these characteristics as matching and control variables.

6.2 Baseline empirical results

Table 3 presents the baseline results based on OLS regressions applied using entropy balancing weights. Specifically, models (1)–(4) provide results for work meaningfulness as the outcome, while in models (5)–(8), the dependent variable is autonomy. The main difference between models (1) and (2), and models (3) and (4), respectively, is the supervisor variable measurement as either a binary or continuous variable. We only report the coefficient estimates related to the variables of interest for brevity, but Table A2 details the full econometric output.

Models (1)–(2) and (5)–(6) of Table 3 confirm other studies’ findings that being your own boss comes with considerable autonomy and meaningfulness benefits compared with wage employees. Specifically, the self-employment work meaningfulness premium is about 2.9–3.0 points on a scale of 0–100 and is statistically significant. A natural question is how big or small this coefficient estimate actually is. Evaluated at the overall sample mean of 50 for work meaningfulness, this is about 6%, which is a relatively moderate impact. Given that the work meaningfulness and autonomy indices are standardized to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10, this corresponds to a difference of about 28–29% of a standard deviation compared to wage employees.Footnote 10 This is an economically significant difference and is especially relevant given that work meaningfulness determines a range of labor market outcomes (Nikolova & Cnossen, 2020; Rosso et al., 2010). Examining models (5)–(6) of Table 3, the autonomy premium of self-employment is about 65–67% of a standard deviation compared to wage employees. Evaluated at the sample mean of 50, this constitutes about 13%.

Table 3 also demonstrates that managing others brings meaningfulness and autonomy compared to being a non-supervisor. Based on the magnitude of the coefficient estimate of the supervisor variable (models (1) and (5)), the difference in work meaningfulness (autonomy) between supervisors and non-supervisors is 8.6% (17%) of a standard deviation. In addition, models (2) and (6) indicate that the number of people the respondent manages positively influences work meaningfulness and autonomy. Specifically, since the number of subordinates is natural log-transformed, we can interpret its coefficient estimate as the autonomy/meaningful consequences of roughly doubling the number of people supervised.

6.3 Empirical tests of H1 and H2

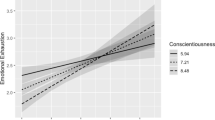

Importantly, Table 3 furnishes empirical tests of Hypotheses 1 and 2, which stipulate the moderating role of being a supervisor for work meaningfulness and autonomy by relying on an interaction term. Specifically, we examine whether and how the relationship between work status (i.e., self-employment or wage employment) and work meaningfulness and autonomy depends on supervising others. We have also calculated the predicted values for all groups based on models (3) and (7) for ease of interpretation and presentation.

The first comparison we are concerned about is between self-employed supervisors vs. wage-employed supervisors (H1). To test this hypothesis, Fig. 1 reports the predicted work meaningfulness for both groups, based on the results presented in model (3) of Table 3. The results suggest that the predicted work meaningfulness of self-employed supervisors is 53 points on a scale from 0–100, whereas that of wage-employed supervisors is 50.59 points on the same scale. In other words, the meaningfulness benefit of being a self-employed supervisor rather than a wage-employed supervisor is the difference of 2.41 points. This difference is statistically significant (F-stat = 74.14, p-value = 0.000). Its magnitude is also modest but economically meaningful: we observe a 4.8% increase in work meaningfulness for self-employed supervisors compared to wage-employed supervisors when evaluated at the sample mean of 50.

Regarding autonomy, based on model (7) of Table 3, Fig. 2 demonstrates that self-employed supervisors experience about 3.19 points more autonomy than wage-employed supervisors (56.86 vs. 53.67, F-stat = 259.42, p-value = 0.0000). The magnitude is economically meaningful: we observe a 5.94% increase in autonomy for self-employed supervisors compared to wage-employed supervisors when evaluated at the sample mean of 50. All in all, these results demonstrate that being a self-employed supervisor provides greater levels of autonomy and work meaningfulness compared with having a similar position for those who are not self-employed. This evidence supports Hypothesis 1.

Furthermore, the intensive margin results in Figs. 3 and 4 provide interesting nuances. Figure 3, based on model (4), demonstrates that this advantage for the self-employed is only up to managing about 55 employees (ln (55) = 4). Beyond that point, there is no difference between the work meaningfulness levels of wage employees and the self-employed. In addition, the intensive margin analysis in Fig. 4 suggests that the advantage for the self-employed supervisors is up until about 55 employees. Beyond that point, salaried supervisors experience more autonomy compared with the self-employed supervisors.

Next, we turn to Hypothesis 2, which postulates that solo self-employment provides fewer autonomy and meaningful benefits than being a self-employed supervisor. The coefficient estimates of the interaction terms in models (3) and (7) and the predicted values in Figs. 1 and 2 demonstrate nuanced results. Specifically, while being a self-employed supervisor is marginally more meaningful than working alone as your own boss, solo entrepreneurs experience substantively more autonomy. The solo self-employed’s predicted work meaningfulness is at 52.42 points, while it is at 53 points for the self-employed supervisor. This difference is very small—approximately a 1.11% increase in work meaningfulness, evaluated at the sample mean of 50. Yet, the difference is statistically significant (F-stat = 10.43, p-value = 0.0012). For autonomy, the solo entrepreneurs’ predicted autonomy levels are at 57.14 points, while self-employed supervisors are at 56.86. Again, this is a rather modest difference (less than 1%), but it is statistically significant (F-stat = 4.38, p-value = 0.0363).

These results may seem paradoxical at first. Nevertheless, they are in line with empirical evidence suggesting that solo entrepreneurs may lack social support (Binder & Blankenberg, 2021) but have more significant preferences for autonomy (van Stel & van der Zwan, 2020). The desire for autonomy and freedom is one of the most important motivations for starting a business (European Commission, 2013; van Gelderen & Jansen, 2006). At the same time, managing others brings work meaningfulness to the self-employed supervisors, likely because it ensures interactions with colleagues and taking responsibility for one’s employees. Yet, it may also bring them less autonomy relative to their solo counterparts because of the associated job demands and stress (Hessels et al., 2017). Therefore, our results only partially support H2.

All in all, Table 3 and Figs. 1 and 2 demonstrate that self-employed supervisors have the highest levels of perceived work meaningfulness compared to any other group. However, it is the solo self-employed who enjoy the greatest benefits of autonomy. This finding may explain the recent increase in solo entrepreneurship in Europe (van Stel & van der Zwan, 2020).

6.4 Robustness checks

Table 4 replicates our findings using Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM) estimation and demonstrates that the results are not sensitive to the matching method. The results are qualitatively similar to the estimates using the entropy balancing method. In contrast to the entropy balancing, the CEM uses a matched sample with a total of 58,001 observations, matching on select covariates—age, gender, education, household size, marital status, and number of children. The matching diagnostics indicate a successful match, as reported by the decreased L1 statistics in Tables A5 and A6 in the Appendix. Overall, the results appear robust to the choice of matching techniques.

In addition, Table A4 reports the OLS results, which generally show similar magnitudes of the coefficient estimates as those based on the two matching techniques. This suggests that our results are generally robust to certain self-selection issues.

Furthermore, in Appendix Table A7, we demonstrate that our baseline findings are insensitive to restricting the regression to the set of common non-missing observations for all analysis variables. The results appear to be slightly smaller in magnitude compared to the baseline specifications. The interaction terms in models (3) and (4) turn insignificant instead of being marginally statistically significant, though they retain their signs and magnitudes. Limiting the sample to the set of non-missing observations does not alter our main conclusions, providing further confidence in our results.

6.5 Potential explanations and alternative dependent variables

This section explores potential explanations for our main findings that (i) self-employed supervisors derive more autonomy and work meaningfulness compared with wage supervisors and (ii) solo entrepreneurs have slightly more autonomy and slightly less meaningfulness compared with self-employed supervisors. To that end, we utilize additional dependent variables capturing stress, working hours, and income (Table 5). The number of observations differs from those in the main analyses in Table 3 due to the availability of these additional dependent variables. For ease of interpretation, Figs. A1–A3 in the Appendix demonstrate the associated marginal effects. First, based on Figs. A1–A3, wage supervisors and self-employed supervisors have statistically indistinguishable levels of predicted stress levels (F-stat = 0.04, p-value = 0.8428), and income (F-stat = 0.60, p-value = 0.4384), and self-employed supervisors have higher predicted working hours, conditional on all of the included controls and entropy balancing weights (F-stat = 12.97, p-value = 0.0003). Yet, despite that, our results demonstrate that they derive more meaningfulness and autonomy from the work that they do, compared with their wage counterparts. This finding suggests that being a self-employed supervisor brings intrinsic work benefits compared with being a wage supervisor.

Second, the findings in Table 5 and Figs. A1–A3 indicate that self-employed supervisors have higher stress, longer working hours, but also higher incomes than solo entrepreneurs. All differences are statistically significant (p-value = 0.0000). The fact that self-employed supervisors are more financially successful may be one reason why they experience slightly more work meaningfulness than solo entrepreneurs. At the same time, the solo self-employed enjoy less stressful and intense working lives, contributing to their higher levels of autonomy.

7 Discussion and conclusion

This study finds that while being your own boss significantly increases autonomy and meaning at work, these non-pecuniary benefits depend on managing others. Self-employed supervisors derive higher perceived work meaning and autonomy compared to managers who are not self-employed. These work meaningfulness and autonomy premia for the self-employed supervisors are despite working longer hours and earning the same as wage supervisors, suggesting that being a self-employed supervisor brings tangible non-monetary benefits not captured by conventional measures of working conditions.

At the same time, however, solo entrepreneurs experience slightly higher levels of work autonomy than self-employed supervisors, even though they experience marginally lower work meaningfulness. This finding is interesting and fits with recent results on the solo self-employed in Europe (e.g., Burke & Cowling, 2020c; van Stel & de Vries, 2015; van Stel & van der Zwan, 2020). In particular, the share of the solo self-employed in Europe has increased in the past decades because firms are looking for more agile and flexible work forms (Burke & Cowling, 2020b, c) and because many workers seek autonomy (van Stel & van der Zwan, 2020). In addition, solo entrepreneurship may be more compatible with home working and caregiving (Kim & Parker, 2020), which may not be more meaningful than being self-employed and employing others but certainly provides freedom and flexibility.

To our knowledge, our paper is the first to demonstrate that the solo self-employed end up experiencing more autonomy compared with any other workers. Of course, the group of solo self-employed is quite diverse (CRSE, 2017). It includes both the precariously employed low-wage necessity entrepreneurs and the highly educated and high-earning freelancers. Yet, our results are not consistent with a precarious employment explanation and indicate that solo entrepreneurs do not perceive these conditions as constraining their autonomy. This may be because solo entrepreneurs experience their working lives as less stressful than supervisors who are self-employed or working as wage employees (Fig. A3). In addition, solo entrepreneurs may have fewer job demands, but high job control or can better manage their work-life balance or family obligations (Kara & Petrescu, 2018). For example, research finds that freelancers in the UK report greater leisure satisfaction than other self-employed workers and salaried employees (van der Zwan et al., 2020). Yet, despite these autonomy benefits, solo self-employment does not bring the same fulfillment and purpose as supervisor self-employment, likely because it limits the ability to communicate and form relationships at work.

Our findings advance the literature in several ways. First, like other papers, we show that entrepreneurship and self-employment can drive important subjective well-being outcomes such as work meaningfulness in addition to job satisfaction and autonomy. However, it is unclear to what extent these outcomes are related to each other. For instance, higher levels of autonomy may allow people to derive more meaning from their work. Similarly, meaningful work can moderate the relationship between autonomy and job satisfaction such that people who have less autonomy at work may still derive high levels of job satisfaction from their work if they find their jobs more meaningful. Given the relevance of work meaningfulness and autonomy for various organizational and well-being outcomes such as withdrawal intentions and organizational commitment (Rosso et al., 2010; Steger et al., 2012), a natural next step will be to examine what other factors may contribute to feelings of meaningfulness at work for both the self-employed and the employed.

Second, and more importantly, our results imply that not all self-employed people derive the same level of autonomy and meaning from their work. Specifically, we find that self-employed supervisors are slightly more likely to experience higher levels of meaning at work relative to entrepreneurs who do not manage others. Yet, as explained, the level of autonomy that the solo self-employed have exceeds that of any other worker group. In that sense, our paper identifies a critical boundary condition in the literature on well-being and entrepreneurship. This is important because many people find entrepreneurship a desirable career option primarily due to its benefits in terms of autonomy.

Nevertheless, our results should be interpreted with caution as they are not causal. The main challenge to identifying causal results is the self-selection in self-employment and supervisory roles. While we have attempted to mitigate these issues using entropy balancing, CEM, and by providing additional robustness checks, we cannot rule out endogeneity issues.

Against this backdrop, our paper leaves many opportune avenues for future research for which additional panel data and causal techniques are urgently needed. For example, longitudinal data availability will allow for further refinement of the methods employed to study the relationships and hypotheses proposed in this paper. They will enable us to understand how work meaningfulness and autonomy change over the entrepreneurial journey for the same individuals. Panel data will also allow using techniques that account for the self-selection into different occupational positions (e.g., solo vs. self-employed supervisor). They will also furnish an understanding of whether career transitions and entrepreneurial failure alter entrepreneurs’ ability to derive meaningfulness from work. In addition, this study’s results are based on a European sample of relatively economically advanced countries. It is an open question of whether the same findings apply in other contexts, and especially in developing countries, where the nature of entrepreneurship is more precarious and necessity-driven.

Notes

Economists typically think of eudaimonic well-being as having meaning and purpose in life (Fabian, 2020; Graham & Nikolova, 2015; Nikolova & Graham, 2020; OECD, 2013). Yet, psychologists view eudaimonic well-being as multi-dimensional and comprising aspects, such as competence, autonomy, personal growth, and relatedness (Ryff, 1989, 2014, 2019). In this paper, we use the terms “work meaning” and “work meaningfulness” synonymously.

For example, in the European Union, about 70% of all self-employed do not have employees (OECD, 2017).

For example, in European countries, most self-employed (about 80%) can set their working hours, and about half can determine the content and order of their tasks (Eurostat, 2018). This allows them to approach their work following their convictions and beliefs, making choices independently of others, which, in turn, can lead to the fulfillment of their basic psychological need for autonomy (Shir et al., 2019).

The most widely-accepted multi-dimensional scale in the psychology literature is the Work as Meaning Inventory (WAMI) (Bailey et al., 2019; Steger et al., 2012), which conceptualizes and measures work meaningfulness as a multi-dimensional eudaimonic state, comprising positive meaning (i.e., a job that the individual views as meaningful), meaning-making through work (i.e., work that enables making sense of the world), and greater good motivations (i.e., having a socially useful job). WAMI reflects individuals’ perceptions about having a job that is worthwhile, meaningful, and has broader social value added. Unfortunately, the WAMI is not collected in any nationally representative survey data, which has limited its use to ad-hoc studies in the psychology literature. Consequently, like in Nikolova and Cnossen (2020), we created a meaningful work measure based on available information in nationally-representative data that most closely matches the WAMI dimensions.

Economists typically define entrepreneurship in terms of business ownership and self-employment, while business scholars prefer studying the behavioral choices related to starting a new venture. As such, in the business literature, entrepreneurship is typically defined in terms of opportunity recognition and new business venture creation amidst risk and uncertainty (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006; Parker, 2018; Shir, 2015). A vast literature in economics uses self-employment data (e.g., Fairlie (1999), Fossen (2020), and Parker and Robson (2004)).

In 2015, the EWCS interviewers had to clarify the following: “By ‘employee’ we mean someone who gets a salary from an employer or a temporary employment agency. ‘Self-employed’ includes people who have their own business or are partners in a business as well as freelancers.” In addition, the questionnaire instructions specified that: “Respondents who work as an employee for their own business should be coded as self-employed. Members of producers’ cooperatives should also be coded as self-employed. Family workers should determine which alternative matches their situation best” (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2015, p. 5). The 2005 and 2010 waves do not include such instructions. To account for possible variations in the measurement of self-employment across the survey waves, we include time and industry fixed effects in the analyses.

Incorporated businesses are arguably a better proxy for entrepreneurship. Incorporated businesses perform cognitive tasks requiring creativity and flexibility, while unincorporated businesses typically engage in non-cognitive activities, such as carpentry, transportation, or landscaping (Levine & Rubinstein, 2017).

To obtain a successful match, the procedure must reduce the distance between all variables (Iacus et al., 2019, 2012). We report the L1 distance for all variables to compare the imbalance measurement before treatment (Appendix Table A5) and after treatment (Appendix Table A5). The L1 distance should be smaller post-treatment for a successful match. A zero indicates no difference between the groups in that category, and the multivariate L1 distance provides an indication of the overall imbalance measurement. A successful match will also reduce this statistic. The results suggest a successful match, since the L1 statistic for each variable as well as the multivariate L1 statistic is smaller in Appendix Table A5 than in Appendix Table A4. As a result, we are able to use the matching weights in our empirical analysis to adjust for the self-selection concern.

Compared with the coefficient estimate for the richest income quartile of about 1, for example, the self-employment premium related to meaningfulness of about 2.9–3.0 points is about 2–3 times larger. Compared with the coefficient estimate for job advancement opportunities of 3.4, the self-employment work meaningfulness premium is a bit smaller.

References

Aleksynska, M. (2018). Temporary employment, work quality, and job satisfaction. Journal of Comparative Economics, 46(3), 722–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2018.07.004

Bailey, C., Yeoman, R., Madden, A., Thompson, M., & Kerridge, G. (2019). A review of the empirical literature on meaningful work: Progress and research agenda. Human Resource Development Review, 18(1), 83–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484318804653

Baron, R. A. (2010). Job design and entrepreneurship: Why closer connections= mutual gains. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(2/3), 370–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.607

Binder, M., & Blankenberg, A.-K. (2021). Self-employment and subjective well-being. In K. F. Zimmermann (Ed.), Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics: Springer Verlag.

Boudreaux, C., Elert, N., Henrekson, M., & Lucas, D. (2021). Entrepreneurial accessibility, eudaimonic well-being, and inequality. Small Business Economics forthcoming.

Burke, A., & Cowling, M. (2020a). The role of freelancers in entrepreneurship and small business. Small Business Economics, 55(2), 389–392.

Burke, A., & Cowling, M. (2020b). On the critical role of freelancers in agile economies. Small Business Economics, 55(2), 393–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00240-y

Burke, A., & Cowling, M. (2020c). The relationship between freelance workforce intensity, business performance and job creation. Small Business Economics, 55(2), 399–413.

Cardon, M. S., Foo, M. D., Shepherd, D., & Wiklund, J. (2012). Exploring the heart: Entrepreneurial emotion is a hot topic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00501.x

CRSE. (2017). The true diversity of self-employment. London: Centre for Research on Self-Employment (CRSE). http://www.crse.co.uk/research/true-diversity-selfemployment.

Dellot, B. (2014). Salvation in a Start-up?: The Origins and Nature of the Self-employment Boom. RSA Action and Research Centre in partnership with Etsy.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Plenum Press.

European Commission (2013). Flash Eurobarometer 354 (entrepreneurship in the EU and Beyond): GESIS Datenarchiv, Köln. ZA5789 Datenfile Version 1.0.0, https://doi.org/10.4232/1.11590.

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2007) European working conditions survey 2005 [Data collection]. UK Data Service. sn: 5639. 10.5255/UKDA-SN-5639-1.

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2012) European working conditions survey 2010 [Data Collection]. UK Data Service. .https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6971-1

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2015). 6th European working conditions questionnaire.

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2017). European working conditions survey 2015 [Data Collection]. 4th edition. UK Data Service. sn: 8098. https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-8098-4.

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2019). European working conditions survey integrated data file, 1991–2015. [Data Collection]. 7th edition. UK Data Service. sn: 7363. https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-7363-7.

Eurostat (2018). Labour Force Survey (LFS) ad-hoc module 2017 on the self-employed persons — Assessment report — 2018 edition. Retrieved from Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-statistical-reports/-/KS-39-18-011.

Fabian, M. (2020). The coalescence of being: A model of the self-actualisation process. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00141-7

Fairlie, R. W. (1999). The absence of the African-American owned business: An analysis of the dynamics of self-employment. Journal of Labor Economics, 17(1), 80–108. https://doi.org/10.1086/209914

Fossen, F. M. (2020). Self-employment over the business cycle in the USA: A decomposition. Small Business Economics, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00375-3

Graham, C., & Nikolova, M. (2015). Bentham or Aristotle in the development process? An empirical investigation of capabilities and subjective well-being. World Development, 68, 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.11.018

Greifer, N., & Stuart, E. A. (2021). Matching methods for confounder adjustment: An addition to the epidemiologist’s toolbox. Epidemiologic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxab003

Gumpert, D., & Boyd, D. (1984). The loneliness of the small-business owner. Harvard Business Review, 62(6), 18.

Gustafsson, A., Stephan, A., Hallman, A., & Karlsson, N. (2016). The “sugar rush” from innovation subsidies: A robust political economy perspective. Empirica, 43(4), 729–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-016-9350-6

Hackman, R. J., & Oldham, G. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(2), 250–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90016-7

Hainmueller, J., & Xu, Y. (2013). ebalance: A Stata package for entropy balancing. Journal of Statistical Software, 54(7), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v054.i07

Hainmueller, J. (2012). Entropy balancing for causal effects: A multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Political Analysis, 20(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpr025

Hessels, J., Rietveld, C. A., & van der Zwan, P. (2017). Self-employment and work-related stress: The mediating role of job control and job demand. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(2), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.10.007

Iacus, S. M., King, G., & Porro, G. (2009). CEM: Software for coarsened exact matching. Journal of Statistical Software, 30(9), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v030.i09

Iacus, S. M., King, G., & Porro, G. (2012). Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpr013

Johnson, J. J. (2000). Differences in supervisor and non-supervisor perceptions of quality culture and organizational climate. Public Personnel Management, 29(1), 119–128.

Kara, A., & Petrescu, M. (2018). Self-employment and its relationship to subjective well-being. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 16(1), 115–140.

Kim, N. K. N., & Parker, S. C. (2020). Entrepreneurial homeworkers. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00356-6

King, G., & Nielsen, R. (2019). Why propensity scores should not be used for matching. Political Analysis, 27(4), 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2019.11

Lepisto, D. A., & Pratt, M. G. (2017). Meaningful work as realization and justification: Toward a dual conceptualization. Organizational Psychology Review, 7(2), 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386616630039

Levine, R., & Rubinstein, Y. (2017). Smart and illicit: Who becomes an entrepreneur and do they earn more? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2), 963–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw044.

Martela, F., & Riekki, T. J. (2018). Autonomy, competence, relatedness, and beneficence: A multicultural comparison of the four pathways to meaningful work. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1157. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01157

McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 132–152. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.19379628

Nikolaev, B., Boudreaux, C. J., & Wood, M. (2020). Entrepreneurship and subjective well-being: The mediating role of psychological functioning. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 44(3), 557–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719830314

Nikolova, M., & Cnossen, F. (2020). What makes work meaningful and why economists should care about it. Labour Economics, 65, 101847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2020.101847

Nikolova, M., & Graham, C. (2020). The economics of happiness. In K. F. Zimmermann (Ed.), Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics. Cham: Springer Verlag.

Olsson, U. (1979). Maximum likelihood estimation of the polychoric correlation coefficient. Psychometrika, 44(4), 443–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296207

OECD (2017), Solo self-employment in the European Union, 2002-16: Number of self-employed without employees and proportion among total self-employment (15-64 years old), in The Missing Entrepreneurs 2017: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, doi: https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264283602-graph4-en.

OECD. (2013). OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being. OECD Publishing.

Pantea, S. (2020). Self-employment in the EU: Quality work, precarious work or both? Small Business Economics, 1–16.

Parker, S. C., & Robson, M. T. (2004). Explaining international variations in self-employment: Evidence from a panel of OECD countries. Southern Economic Journal, 287-301. https://doi.org/10.2307/4135292

Parker, S. C. (2018). Introduction. In S. C. Parker (Ed.), The Economics of Entrepreneurship (2nd ed., pp. 1–18). Cambridge University Press.

Parker, S. C. (2009). The economics of self-employment and entrepreneurship. Cambridge University Press.

Prottas, D. J., & Thompson, C. A. (2006). Stress, satisfaction, and the work-family interface: A comparison of self-employed business owners, independents, and organizational employees. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(4), 366–378. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.4.366

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Ryff, C. D. (2014). Self realization and meaning making in the face of adversity: A eudaimonic approach to human resilience. Journal of Psychology in Africa (south of the Sahara, the Caribbean, and Afro-Latin America), 24(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2014.904098

Ryff, C. D. (2017). Eudaimonic well-being, inequality, and health: Recent findings and future directions. International Review of Economics, 64(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-017-0277-4

Ryff, C. D. (2019). Entrepreneurship and eudaimonic well-being: Five venues for new science. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(4), 646–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.09.003

Shane, S. A. (2008). The illusions of entrepreneurship. Yale University Press.

Shir, N. (2015). Entrepreneurial Well-being: The Payoff Structure of Business Creation: Stockholm School of Economics.

Shir, N., Nikolaev, B. N., & Wincent, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship and well-being: The role of psychological autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(5), 105875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.05.002

Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711436160

Stephan, U. (2018). Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: A review and research agenda. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(3), 290–322. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0001

Stephan, U., Tavares, S. M., Carvalho, H., Ramalho, J. J., Santos, S. C., & van Veldhoven, M. (2020). Self-employment and eudaimonic well-being: Energized by meaning, enabled by societal legitimacy. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(6), 106047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106047

van der Zwan, P., Hessels, J., & Burger, M. (2020). Happy free willies? Investigating the relationship between freelancing and subjective well-being. Small Business Economics, 55(2), 475–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00246-6

van Gelderen, M., & Jansen, P. (2006). Autonomy as a start-up motive. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000610645289

van Stel, A., & van der Zwan, P. (2020). Analyzing the changing education distributions of solo self-employed workers and employer entrepreneurs in Europe. Small Business Economics, 55(2), 429–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00243-9

van Stel, A., & de Vries, N. (2015). The economic value of different types of solo self-employed: A review. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 13(2), 73–80.

Wiklund, J., Nikolaev, B., Shir, N., Foo, M.-D., & Bradley, S. (2019). Entrepreneurship and well-being: Past, present, and future. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(4), 579–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.01.002

Wiklund, J., Davidsson, P., & Delmar, F. (2003). What do they think and feel about growth? An expectancy–value approach to small business managers’ attitudes toward growth. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(3), 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.t01-1-00003

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Editor Thomas Åstebro and two anonymous referees for extensive comments and feedback. In addition, we have benefitted from the comments and suggestions of Antje Schmitt, Marjan Gorgievski, and participants at the 2020 Entrepreneurship Research Meeting at the University of Groningen. Finally, we thank Viliana Milanova for proofreading the final version of the manuscript. All errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nikolova, M., Nikolaev, B. & Boudreaux, C. Being your own boss and bossing others: the moderating effect of managing others on work meaning and autonomy for the self-employed and employees. Small Bus Econ 60, 463–483 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00597-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00597-z