Abstract

Scholars and practitioners continue to recognize the crucial role of entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs) in creating a conducive environment for productive entrepreneurship. Although EEs are fundamentally interaction systems of hierarchically independent yet mutually dependent actors, few studies have investigated how interactions among ecosystem actors drive the entrepreneurial process. Seeking to address this gap, this paper explores how ecosystem actor interactions influence new ventures in the financial technology (fintech) EE of Singapore. Guided by an EE framework and the use of an exploratory-abductive approach, empirical data from semi-structured interviews is collected and analyzed. The findings reveal four categories representing both the relational perspective, which features interaction and intermediation dynamics, and the cultural perspective, which encompasses ecosystem development and regulatory dynamics. These categories help explain how and why opportunity identification and resource exploitation are accelerated or inhibited for entrepreneurs in fintech EEs. The present study provides valuable contributions to scholars and practitioners interested in EEs and contributes to the academic understanding of the emerging fintech phenomenon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

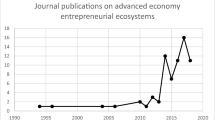

The concept of entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs) has gained extensive attention in recent years (Malecki, 2018; Roundy, 2016; Spigel & Harrison, 2018) due to its explanatory power, which combines social, institutional, and relational aspects (Brown & Mason, 2017). However, the growing focus on EEs has caused many unexplored and underexplored areas to emerge, so scholars have called for theoretical and empirical studies to help fill gaps in the literature (Audretsch et al., 2018; Brown & Mason, 2017; Spigel, 2017; Stam, 2015). For example, scholars have stressed the need to explore ecosystem dynamics, conceptualized as interactions that occur among entrepreneurs and ecosystem actors, by adopting a network approach (e.g., Alvedalen & Boschma, 2017; Brown & Mason, 2017; Motoyama & Knowlton, 2017). Existing studies focus on the causal relations between individual ecosystem actors or EEs as a whole and entrepreneurial output but remain relatively silent on how interactions between different ecosystem actors contribute to new venture creation (Alvedalen & Boschma, 2017; Stam, 2015). In response, the present study employs Brown and Mason’s (2017) taxonomy to investigate four ecosystem categories: entrepreneurial actors, resource providers, connectors, and entrepreneurial culture. Other prominent EE frameworks (e.g., Isenberg, 2011; Spigel, 2017) have included these elements; however, they have focused either on an ecosystem’s composition (Isenberg, 2011) or relationships between ecosystem attributes (Spigel, 2017). Conversely, Brown and Mason’s (2017) conceptualization attempts to capture the full complexity of EEs through their underlying dynamics.

Traditionally, empirical investigations (e.g., Audretsch & Belitski, 2017; Liguori et al., 2019; Neck et al., 2004; Spigel, 2017) have primarily viewed EEs from the entrepreneur’s perspective. At the same time, scholars have argued that entrepreneurship is not an independent act but one that takes place in a society of interrelated actors (Stam, 2015) who might not be directly related to entrepreneurial ventures. This may include established firms, universities, public institutions, and capital providers (Isenberg, 2010). As such, EEs are interaction systems that consist of hierarchically independent yet mutually dependent ecosystem actors (Autio, 2016). It is further argued that the role of these actors is downplayed in EE studies; for instance, Brown and Mason (2017) state that established organizations play a vital role in ecosystems because they attract human resources, incubate startups, and usually serve as first customers. For these reasons, scholars have called for studies to explore the interplay among other actors in the external environment (Cavallo et al., 2018; Ghio et al., 2019; Nicotra et al., 2018). In addition, recent studies (e.g., Motoyama & Knowlton, 2017; Neumeyer et al., 2019) have begun exploring multiple perspectives, empirically investigating stakeholders like investors, government actors, incubator managers, and academics. Building on these efforts, we investigate the dynamics between entrepreneurs and ecosystem actors in EEs. Thus, we go beyond typical empirical investigations in the EE literature to explore the experiences of a diverse set of ecosystem actors with profound influence on the success—or failure—of entrepreneurship.

Not all context-specific knowledge can be readily transferred to other contexts due to its distinctive characteristics; hence, we may assume that ecosystem dynamics in certain industry-specific EEs are different compared to other contexts (Autio et al., 2014). Building on this argument, we focus our empirical investigation on the financial industry, which has been profoundly impacted by digitalization, and look particularly at the financial technology (fintechFootnote 1) phenomenon. In addition to the effect of digitalization on the identification and acquisition of entrepreneurial opportunities (Autio et al., 2018), fintech is characterized by the proliferation of newcomers, financial stability risks (Anagnostopoulos, 2018; Li et al., 2020; Magnuson, 2018), and changes in the regulatory environment (Arner et al., 2015). These characteristics challenge and reshape the existing dynamics among ecosystem actors (Gazel & Schwienbacher, 2020; Haddad & Hornuf, 2019; Hornuf et al., 2020).

The present exploratory study addresses the following research question (RQ): How are ecosystem dynamics accelerating or inhibiting new ventures in fintech EEs? We answer this RQ through an empirical investigation of the fintech EEFootnote 2 of Singapore, which has recently emerged as a leading fintech hub and is now ranked third globally behind the UK and the USA (Findexable, 2020). The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) reported the presence of 1100 fintech firms in 2019, compared to fewer than 100 in 2016 (MAS, 2020b). Additionally, 2019 saw the value of investment deals more than double to US$861 million, with 40% of the capital raised by digital payment fintechs (Accenture, 2020). These achievements are no accident, as Singapore has cultivated a favorable climate for fintech, with MAS functioning as both regulator and innovation catalyst, giving it a first mover advantage in Asia and around the world. Despite this growth, little academic attention has been paid to Singapore, unlike other fintech EEs such as the UK and China (Lin, 2019).

Methodologically, we answer the RQ through a qualitative research design employing an exploratory-abductive approach (Dubois & Gadde, 2002) as a steppingstone to propose theoretical propositions. In-depth semi-structured interviews are conducted with a diverse set of fintech ecosystem actors in Singapore. For data analysis, the Gioia method (Gioia et al., 2013) is coupled with systematic combining (Dubois & Gadde, 2002), following a non-linear, non-positivistic approach to theory generation.

Through this study, we extend the existing knowledge of EEs by offering a set of theoretical propositions on the dynamics of fintech ecosystems, thus responding to numerous calls for empirical studies (e.g., Audretsch et al., 2018; Spigel, 2017). We also extend the scholarly understanding of how the fintech context is linked to the EE literature stream (Lee & Shin, 2018). Additionally, by employing Brown and Mason’s (2017) EE framework, the present study contributes to the emerging fintech phenomenon, which remains underexamined and anecdotal in management research (Puschmann, 2017). Last, this study contributes to practice by informing entrepreneurs about opportunities to access networks and exploit resources; practical implications for policymakers are also identified.

The paper is structured as follows: in the next section, we briefly introduce the concept of EEs and establish fintech as an industry-specific ecosystem. We then review the theoretical approach adopted and the EE framework that guides the empirical investigation. A case description is accompanied by an explanation of the research process before the empirical findings are presented. The discussion section suggests theoretical propositions, discusses the obstacles within the fintech EE, and describes the implications of this study for both theory and practice; a brief conclusion follows.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Entrepreneurial ecosystems

Acs et al. (2017), among others, position the EE concept within the strategy literature, linking it directly to ecosystem concepts that first included business ecosystems (Moore, 1993). The EE concept differs from prior literature (e.g., national and regional innovation systems) by its emphasis on entrepreneurs as focal actors and on the social, institutional, and relational aspects of ecosystem actors (Brown & Mason, 2017; Nicotra et al., 2018; Stam, 2015). It is used as a framework to explain social interactions among actors in the entrepreneurship process and local environment (Spigel & Harrison, 2018). Audretsch and Belitski (2017) define EEs as “institutional and organizational as well as other systemic factors that interact and influence identification and commercialization of entrepreneurial opportunities” (p. 1031). The authors refer to EEs as geographically bounded cities like Boston, characterized by the presence of supportive academic institutions, policies and infrastructure, industry actors, support organizations, entrepreneurial culture, and investment power (Audretsch & Belitski, 2017). All these elements influence the creation of local ventures by facilitating knowledge sharing and access to resources (Colombelli et al., 2019; Neck et al., 2004; Spigel, 2017). EE scholars are currently investigating the dynamics among ecosystem actors rather than simply identifying the role played by ecosystem elements in entrepreneurial activity (Audretsch et al., 2018; Di Fatta et al., 2018; Ghio et al., 2019).

Qualitative investigations of EEs have examined geographical locations rather than specific industries (McAdam et al., 2019; Scheidgen, 2020; Spigel, 2017). For instance, Spigel (2017) explores new ventures operating in various industries in the ecosystems of Calgary and Waterloo in Canada. While these studies provide valuable contributions to our knowledge of EEs, their findings are not industry specific. That said, it is not a given that all knowledge from empirical investigations of EEs can be generalized across industries because of differences in the characteristics of each sector. Hence, we may assume that the role of ecosystem actors in certain industry-specific EEs differs in other contexts like digitalized industries (Autio et al., 2018). Digitalization in this setting reduces “the dependency of new ventures on cluster-specific spatial affordances for entrepreneurial opportunities, while also alleviating some of the spatial constraints of opportunity pursuit and enabling new ventures to experiment with and discover business models that exploit opportunities external to the cluster” (Autio et al., 2018, p. 80). On this basis, we narrow our investigation to the financial sector due to the proliferation of market participants, associated risks to financial stability, changes in the regulatory environment, and other contextual conditions such as access to infrastructure, talent, and capital. Taken together, these factors challenge the existing dynamics among key ecosystem actors and consequently the creation and growth of new fintech ventures (Gazel & Schwienbacher, 2020; Hornuf et al., 2020; Svensson et al., 2019). The next section describes the complex fintech landscape.

2.1.1 Fintech EEs

According to Autio et al. (2018), digitalization affects both the type of entrepreneurial opportunities being formed and how such opportunities are sought by founders. Hence, the digital economy provides numerous opportunities for newcomers to innovate and potentially challenge established institutions in the targeted sectors (Gazel & Schwienbacher, 2020). The financial sector offers a good example of how digitalization has enabled fintech newcomers to aggressively penetrate the market, forcing traditional financial institutions (FIs) to become more open to market engagement through strategic alliances or incubation programs (Hornuf et al., 2020). According to PwC, 88% of incumbents are concerned about losing revenue to fintech entrants, whereas 82% expect an increase in partnerships with fintechs in the next 3 to 5 years (PwC, 2017). Changes in financial market dynamics are considerably recent to this context which has traditionally been characterized by low innovation levels (Beck et al., 2016), creating a void between research and practice due to the lack of empirical data exploring the fintech phenomenon (Anagnostopoulos, 2018). This is not to overlook academic contributions on niche fintech segments such as initial coin offerings (ICOs) or crowdfunding (e.g., Adhami et al., 2018; Vismara, 2016). Rather, there is a need for more studies that explore fintech as a phenomenon capturing a broader range of technology-powered financial service providers (e.g., Gazel & Schwienbacher, 2020; Haddad & Hornuf, 2019; Hornuf et al., 2020). This is particularly important when fintech innovations (e.g., crowdfunding or ICOs) complement the growth of other fintech segments in ways like raising capital. While fintech is about not only new ventures but also traditional FIs and technology firms, this study focuses on startups due to their economic impact and disruptive innovations (Palmié et al., 2019). Hence, we use the term “fintech EEs” to represent new ventures and entrepreneurs as focal actors in the financial industry endeavoring to deliver “new business models, applications, processes or products” (Financial Stability Board, 2017, p. 7).

It is important to study the fintech phenomenon, given the increasing numbers of market participants across diverse segments like digital payments, wealth management, crowdfunding, lending, capital market, and insurance (Lee & Shin, 2018). Accenture has reported that, since 2005, fintech providers have captured a third of total global banking revenues (Accenture, 2018). A more recent report enumerates the presence of 90 fintech unicornsFootnote 3 globally by early 2020 with an aggregated value of approximately US$500 billion (Crunchbase, 2020). Over the past decade, global investment in fintech grew roughly ninefold, with US$43 billion invested in 2019 compared to US$5 billion in 2010 (Crunchbase, 2020). Financial regulation scholarship has commonly depicted traditional FIs as the primary drivers of instability and systemic risk to economies (Magnuson, 2018). This argument may no longer be the only valid explanation in light of the increased market penetration of fintech newcomers that decentralize and automate financial services in new ways that lead to three main challenges (Anagnostopoulos, 2018; Li et al., 2020; Magnuson, 2018). First, fintechs are more vulnerable to external market shocks, either because adequate stress-testing may have not been carried out in drastic situations (Anagnostopoulos, 2018) or due to a lack of industry experience and understanding of financial regulations (Philippon, 2016). Second, regulators can scarcely monitor the activities of fintech firms due to their exponential developmental pace. Alibaba’s Yu’E Bao (a fund management fintech) illustrates how rapidly fintech firms can grow, surpassing JP Morgan’s US fund to become, in a mere nine months, the world’s largest market fund. In this scenario, the Chinese regulator’s passive approach would have been inadequate to identify and interfere in the event of systemic threats (Anagnostopoulos, 2018). Aside from the need to keep up with fintechs, regulators must also acquire critical expertise to sustain quality supervision (Boot et al., 2021). Third, fintechs are incentivized to adopt non-cooperative behaviors, partly due to ambition to become a frontrunner and achieve short-term gains, but also because most fintech investors are venture capitalists who demand accelerated growth (Magnuson, 2018). Additionally, such hastiness can raise questions about the integrity of fintechs; Thakor (2020) presented instances of overlending and scandals from P2P lending platforms that lead to investors departing as well as negative effects on market stability. Taken together, these challenges may mean that fintech firms pose greater systemic risk concerns than established FIs (see Magnuson, 2018 for an overview). Not only this, a recent empirical investigation showed that risk spillovers from fintechs to established FIs are positively correlated with the systemic risk of FIs (Li et al., 2020).

In addition to the above characteristics that distinguish the fintech context from others, the role of regulators has been subject to extensive discussions due to regulation’s double-edged sword: regulatory intervention can either impede or support innovation (Alaassar et al., 2020; Cumming & Schwienbacher, 2018; Haddad & Hornuf, 2019). For example, regulations may not support the different and unbundled way fintechs operate in; lenders and borrowers are instantly matched in crowdfunding platforms powered by Big Data analytics, in contrast to bank loans based on long-term relationships (Navaretti et al., 2017). Adding to this complex scenario, fintech newcomers may lack crucial knowledge of regulatory frameworks to navigate through this space (Arner et al., 2015). Furthermore, enabling technologies allow the delivery of financial services to underserved users and unbanked individuals, which affects existing value networks and may pressure FIs to down-scale or relocate due to lower demand (Anagnostopoulos, 2018).

Based on the above, we may argue that rules of the game in financial markets have changed; new fintech players have emerged alongside a supportive ecosystem in the external environment (Block et al., 2018). For example, academic institutions have begun to establish educational programs to upskill talent (Kursh & Gold, 2016). Support organizations are creating accelerator programs and co-working spaces (Arner et al., 2015; Block et al., 2018). Financial market regulators have introduced new initiatives like regulatory sandboxesFootnote 4 and innovation hubs (Jenik & Lauer, 2017; Zetzsche et al., 2017), whereas capital providers have ensured the availability of funds (Haddad & Hornuf, 2019). Other fintech ecosystem actors include technology firms, government institutions, and traditional FIs (Lee & Shin, 2018). While comparing fintech EEs to other ecosystems is beyond the scope of this study, we acknowledge that financial markets share similarities with other industries like the energy sector or pharmaceuticals in terms of stringent regulations and use of enabling technologies. However, we argue that industry-specific characteristics like the increase of market participants coupled with the ability to scale rapidly, large amounts of raised capital, and impact on financial stability, make the fintech context relevant for dedicated research. Within this vibrant environment, ecosystem actors interact to access resources and exploit opportunities, thereby transforming the status quo of the ecosystem dynamics in financial markets. That said, given that the fintech literature remains in its nascency (Gazel & Schwienbacher, 2020), there remains a lack of evidence-based research that explores the dynamics of fintech EEs, a gap that the present study seeks to fill. Figure 1 visualizes the salient features of fintech EEs within broader EEs.

2.2 Conceptualizing ecosystem dynamics

Entrepreneurial dynamics commonly refers to the lifecycle of startups: creation, growth, and stability or exit (Kazanjian, 1988). The existing entrepreneurship literature (e.g., Gartner, 1985) argues that interaction among actors in the external context may impact entrepreneurial dynamics. For instance, Grimaldi and Grandi (2005) investigated the influence of interaction among incubators and incubatees on entrepreneurial creation dynamics, while Pena (2004) examined the growth dynamics resulting from such interactions. More recently, Alaassar et al. (2020) explored the impact of interactions on the practices of fintech startups and regulators in the context of regulatory sandboxes. However, none of these studies use an ecosystem perspective to capture the role of other actors (Cavallo et al., 2018). Neck et al. (2004) conducted one of the first studies to investigate the interactions of founders with multiple actors in entrepreneurial systems; they conclude that regional entrepreneurial activity is influenced by the collective effort of ecosystem actors. In this literature stream, Spigel (2017) argues that successful EEs should not necessarily be determined based on high rates of entrepreneurship but rather by how interactions among ecosystem actors foster entrepreneurial activity. That said, existing research has largely focused on identifying what defines ecosystems in terms of actors and factors that impact entrepreneurial activity while overlooking relational factors that explain how ecosystem elements interact (Alvedalen & Boschma, 2017; Ghio et al., 2019; Stam, 2015). On one hand, the literature assumes that interactions among entrepreneurs can inspire newcomers to start a business with exemplary role models and provide direct business support through mentorship (Brown & Mason, 2017). On the other, interactions among ecosystem actors have been highlighted as crucial to fostering collaboration with local entrepreneurs and providing them access to resources (Feld, 2012). An empirical investigation of EEs in St. Louis, Missouri, supports this finding, indicating that “the way in which entrepreneurs interact and form relationships, leading to support, learning, and growth, was substantially influenced by the way support organizations interacted and by the way the support that they offered was structured” (Motoyama & Knowlton, 2017, p. 27). It can thus be argued that entrepreneurial dynamics is at the core of understanding how ecosystems succeed in creating a supportive environment for entrepreneurship (Stam, 2015). On this basis, following Cao and Shi (2020), we conceptualize ecosystem dynamics as interactions that occur among entrepreneurs and ecosystem actors.

2.3 Theoretical approach

A network approach is employed to guide the empirical investigation in this research, emphasizing the importance of the relational view to entrepreneurship to enable founders to access resources in the external environment (Aldrich & Zimmer, 1986). This approach is characterized by the relations among network actors, which can be in the form of communicating information, exchanging services, or, in a normative sense, expectations and obligations (Aldrich & Zimmer, 1986). Given the qualitative nature of this work, a metaphorical analysis is conducted to explore the relationships between ecosystem actors rather than an analytical assessment that quantitatively measures network structures, a distinction introduced by Bergenholtz and Waldstrøm (2011). Metaphorical studies imply the presence of diverse social interactions among network actors (e.g., Santoro & Chakrabarti, 2002), while analytical studies approach networks in a more formal manner, examining particular social structures through, for instance, social network analysis (e.g., Díez-Vial & Montoro-Sánchez, 2016).

2.3.1 EE framework

Most cited EE frameworks include Isenberg (2011) and Spigel (2017). Isenberg (2011) reports that successful ecosystems are influenced by six domains: a supportive culture, enabling policies, access to sufficient capital, availability of a talent pool, accessible markets, and a diversified set of support organizations and infrastructure. Spigel (2017) develops and empirically investigates a framework comprised of three main attributes that play key roles in the early development of new ventures. These attributes consist of cultural (common norms and values), social (networks to ensure resource acquisition and knowledge flow), and material (tangible elements including policy and governance). While both frameworks involve similar domains, they differ in their emphasis on the composition of ecosystems (Isenberg, 2011) or the relationships among an ecosystem’s attributes (Spigel, 2017). Using these frameworks as a starting point, the present study adopts the conceptualization offered by Brown and Mason (2017) because it attempts to capture the full complexity of ecosystems by investigating the underlying dynamics of four coordinative categories. These include entrepreneurial actors, resource providers, connectors, and entrepreneurial culture. In this study, we use this conceptualization to assist with data collection and data analysis, guiding the exploration of variance that emerges empirically in each category. Each category is described below, and Fig. 2 presents the research model.

adapted from Brown and Mason (2017)

Exploring ecosystem dynamics;

Entrepreneurial actors are widely considered by scholars to be focal actors in EE frameworks (Isenberg, 2011; Spigel, 2017; Stam, 2015). While the concept of EEs may imply that relational factors mediate entrepreneurial activity in the local context, Brown and Mason (2017) argue that recognition needs to be given to non-local interactions that occur between founders and external actors. The role of entrepreneurial actors is crucial for the growth of ecosystems because interactions among entrepreneurs positively impact the perceptions of individuals toward entrepreneurship through spillover effects like the transfer of knowledge, startup spirit, and other resources. This process is referred to as entrepreneurial recycling and can involve entrepreneurial actors who function as serial entrepreneurs, intermediaries, advisors, mentors, and board members. Relatedly, this process may foster investment in local EEs as entrepreneurs re-invest in newcomers following successful exits (Brown & Mason, 2017). That said, the availability of knowledgeable entrepreneurs in an ecosystem is also linked to the presence and quality of universities and research institutions, which can raise the level of competence for entrepreneurial actors (Neck et al., 2004; Nicotra et al., 2018). Additionally, the generation of academic spin-offs is increasingly cited as a key role of local universities (e.g., Meoli et al., 2019).

Entrepreneurial resource providers facilitate the transfer of resources into growing firms by providing sources of financing, support structures, and public sector services (Brown & Mason, 2017). Specifically, financial capital providers may include traditional banks, VCs, business angels, and alternative funding sources like microfinance, crowdfunding, and P2P lending (Bruton et al., 2015). As for support structures, these commonly take the form of incubation models such as business incubators and accelerators (Mian et al., 2016) that enable startups through mentoring, co-working spaces, access to networks, capital, knowledge, and so on (Bøllingtoft & Ulhøi, 2005). Lastly, public sector intervention in ecosystems is an important measure to combat market entry barriers such as regulation and access to capital. The creation of regional venture capital funds that facilitate business angel networks and indirect support of incubation models is a commonly employed solution (Mason, 2009). Additionally, policymakers may enable entrepreneurs’ practices by eliminating inhibiting policies or easing regulations (Nicotra et al., 2018).

Entrepreneurial connectors support EEs by mediating relationships, connecting entrepreneurs to ecosystem actors like investors, industry partners, and mentors. Thus, founders overcome the resource deficiencies that inhibit their access to financial and knowledge capital; accordingly, new venture creation is facilitated (Brown & Mason, 2017; Sullivan & Ford, 2014). Entrepreneurial connectors can also be former founders and serial entrepreneurs or organizations and programs funded by industry or the state (Brown & Mason, 2017).

Entrepreneurial culture is conceptualized as norms, attitudes, and contributions regarding entrepreneurship at the societal level (Brown & Mason, 2017; Isenberg, 2011). The literature stresses the importance of a positive entrepreneurial culture in supporting social capital in EEs because it fosters the relationships between entrepreneurs and other ecosystem actors (Nicotra et al., 2018). These relationships attract ambitious entrepreneurs and thus lead to a higher number of startups scaling into larger firms that are either acquired or undertake an initial public offering (Brown & Mason, 2017; Saxenian, 1996). However, EEs can also have a culture that inhibits entrepreneurs simply because entrepreneurship is not valued or is perceived negatively by a society (Isenberg, 2011).

3 Method

We rely on a qualitative research design using an exploratory-abductive approach (Dubois & Gadde, 2002) to develop new explanations in the form of theoretical propositions. This approach is well suited to studying a new phenomenon with limited knowledge and to facilitate “theory development rather than theory generation” (Dubois & Gadde, 2002, p. 559). An exploratory approach using in-depth interviews with multiple stakeholders has also been deemed necessary in the fintech context (e.g., Mention, 2020).

3.1 Case description

We deliberately selected Singapore as our empirical case to investigate ecosystem dynamics. Singapore is a high-income, entirely urban country of more than 5.6 million people with high internet connectivity (82.1%) and per capita cell phone (1.5) rates (Medici, 2019). It ranks second in the world for ease of doing business and fourth for starting a business (World Bank Group, 2020) and is well-recognized as a global hub where east meets west, fostering a unique business culture (Suseno & Standing, 2018). Singapore’s financial market is the world’s fifth most competitive financial center, according to the Global Financial Centre Index (Morris et al., 2020), and second globally in digital competitiveness in the IMD Digital Competitiveness Ranking (Bris & Cabolis, 2020). Specific to fintech EEs, the Findexable Global Fintech Index ranked Singapore as third behind the UK and the USA (Findexable, 2020). We further extend our case description to discuss how Singapore enjoys a commanding lead in the fintech race, creates a conducive environment for fintechs, and fosters international collaboration.

Singapore has recently emerged as a leading fintech hub, having pioneered several initiatives. First, the API Exchange (APIX) is an open-architecture platform to help FIs discover fintechs and allow FIs and fintechs to collaboratively design and run experiments. Second, the Singapore FinTech Festival (SFF), the world’s largest fintech event, fosters connection and collaboration, with 60,000 attendees in 2019. Third, Sandbox Express, a support instrument to fast-track testing activities (unlike the mainstream regulatory sandbox with longer approval times; MAS, 2020b). These initiatives are in addition to publicly funded grants to support business development at the national and international levels, the creation of innovation labs, and the adoption of enabling technologies (Lin, 2019; MAS, 2020a). On the regulatory front, MAS has also made key legislative changes to enable fintech innovations, including the Payment Services Act, which regulates payment systems and service providers like digital payment tokens (MAS, 2020d).

Singapore sustains a fintech-conducive EE in two main ways. The first is creating platforms to connect fintechs to local and non-local ecosystems, each serving a specific objective. The ASEAN Financial Innovation Network is a regional initiative to help FIs and fintechs through platforms like APIX. Business sans Borders is a transnational innovation platform for small- and medium-sized enterprises. The Singapore FinTech Association is a non-profit organization that facilitates collaboration among stakeholders in the fintech ecosystem. Moreover, the FinTech Research Platform is an investment and partnership space that connects investors and FIs to fintechs (Lin, 2019; MAS, 2020b). The second way Singapore provides a fintech-friendly EE is by fostering cooperation with international counterparts. As of Q2 2020, MAS had signed 33 agreements to promote innovation in financial markets through information sharing, referrals and joint projects (MAS, 2020c).

3.2 Sampling

This study used purposive and snowball sampling procedures to recruit interviewees and achieved triangulation by investigating the perspectives of different ecosystem actors (Patton, 1990). Our selection criteria consisted of (1) being currently engaged as an entrepreneurial actor (e.g., founder, role model, serial entrepreneur), resource provider (e.g., investor, advisor, regulator, researcher), or connector (e.g., incubator manager, former founder) in the financial market industry with respect to any fintech segment and (2) being based in Singapore. Using these criteria, a list of the best-funded fintech startups was established using CrunchBase. Support organizations, VCs, and other relevant ecosystem actors were identified through online searches, including an online talent portal available through the Singapore FinTech Association. More than 125 eligible participants were contacted through LinkedIn; further interactions occurred with 38 participants. Ongoing interviews were then conducted upon participant agreement, and snowball sampling was used to recruit additional interviewees. Using this approach, a total of 19 interviews were conducted. The participants comprised of nine entrepreneurs, six support organization managers, three VCs, and one regulator. Most participants had multiple roles in fintech EEs (both local and non-local), including mentor, investor, and educator. Table 1 provides an overview of the participants.

3.3 Data collection and analysis

The interviews, which lasted an average of 50 min, were conducted remotely through Skype (8 of 19 were video calls) between January and March 2020 and followed a semi-structured format. Recorded calls were transcribed and prepared for analysis. Since different ecosystem actors participated, the interview guide was adapted to explore each participant perspective. Open-ended questions that focused on exploring participants’ current and previous experiences of the ecosystem were posed to participants, including how the fintech EE looked to them, which ecosystem actors they interact(ed) with, and how they access(ed) networks and exploit(ed) resources (Fig. 1). Additionally, the interviews explored the relationships among ecosystem actors and their influence on practices like networking, financing, supporting, and connecting.

For data analysis, we combined the Gioia method, which provides a two-step process to achieve systematic data reduction (Gioia et al., 2013), with an abductive approach that keeps prior research in the frame and enables an analytical framework to guide the analysis and confront theory (Dubois & Gadde, 2002). As such, a process of systematic alternation between the framework, the literature, empirical data, and the case analysis was carried out (Dubois & Gadde, 2002). For the first round of coding, which resulted in 1st order concepts, we started with the preconceptions of the EE framework (Brown & Mason, 2017). Thus, we began coding with a preliminary scheme to explore categories that describe the role of each actor’s perspective with respect to his or her interactions with other ecosystem actors, access to networks and resources, and perceived attitudes and norms. As we progressed, additional categories emerged inductively; more patterns were then identified, and categories were distilled as presented. Hence, this round of analysis resembles a combination of data-driven and theory-driven approaches. For the second round of coding, abstract themes that describe ecosystem dynamics were created, which required shifting back and forth between the literature and analysis (Dubois & Gadde, 2002). Once relationships were established and relevant concepts connected, we considered the possibility of further distilling the 2nd order themes into aggregated dimensions (Gioia et al., 2013). The NVivo 12 software package was used to facilitate the analytical procedure (Gaur & Kumar, 2018).

4 Findings

In this section, we report the findings that emerged from the analysis of interview data to explore the influence of ecosystem dynamics on startups in Singapore. The findings reflect the perspective of entrepreneurial actors, resource providers, and connectors. Figure 3 outlines how the data was processed into aggregated dimensions that capture the relational and cultural perspectives.

4.1 Relational perspective

4.1.1 Interaction dynamics

Our analysis of the perspectives of entrepreneurial actors captured two categories in which social interactions occur and create value in Singapore’s fintech EE: (1) co-creation with fintech startups and (2) resource recycling.Footnote 5 From the perspective of all ecosystem actors, two categories captured the role of (3) governmental actions and (4) financial and knowledge capital transfer in enabling (or impeding) interaction dynamics. Additionally, an interaction pattern of (5) horizontal networks was common to all perspectives that emerged from the data.

In terms of fintech startup co-creation, the data suggests that fintechs work together through formal or informal agreements to access market data or integrate solutions from other players to provide a holistic solution. For example, one interviewee said, “they [a Hong Kong-based bank] wanted to build a digital bank. They selected us to be the core banking technology. Over the last two years, 43 different vendors and partners have contributed towards delivering the end product. We had to work with a payment processor provider [a UK-based fintech startup] to deliver the end state’s architecture. We now have a partnership credential with that provider that we use when approaching other banks” (Ent-7). Our findings also reveal that established startups leverage other channels like local accelerators to connect with early-stage fintechs for assistance with technology utilization or development of proof of concept (PoC). Notably, the founders we interviewed had multiple roles in the ecosystem, such as mentorship in support associations or platforms. Through these engagements, entrepreneurs can benefit in different ways, including potential partnerships and access to data. Our findings revealed that fintech startups are willing to work with emerging fintechs that provide niche solutions to unregulated segments of financial markets that are growing rapidly but lack the support of resource providers and the endorsement of regulators. For example, one entrepreneur said, “we have two clients that are fintech firms setting up as private exchanges, competing with actors like the SG [Singapore] Exchange and the London Stock Exchange to facilitate active trade in unlisted startups on an exchange. Through our network of analysts, we help by providing research on unlisted companies, which also isn’t easy to come across” (Ent-4).

For the second category, resource recycling, we found that fintech startups can play a central role in circulating resources within financial markets; this view surfaced with respect to banks and FIs that either integrate fintech solutions or use their efficient infrastructures. A startup interviewee reported that “one of our partnering banks uses our remittance infrastructure to improve remittance service for their bank customers” (Ent-2). Another fintech startup operating in the capital market space to provide a platform for independent research analysts shared its important ecosystem role of increasing the visibility of corporates to investors: “Through our partnership with the SG Exchange, we provide the corporates with the ability to access the platform, their listed corporates, be discovered by analysts, and get invested in by the investors. Again, there’s a shared interest. And we have a commercial relationship with the SG Exchange, which recently became a small investor in us” (Ent-4). Another and even more interesting perspective emerging from the data describes the contribution of entrepreneurial actors to the regulatory change process: “What you read there [on MAS] is basically what our community is telling MAS as to how they should tackle emergent fintech issues. For example, over an 18-month period, we had discussions with MAS through workshops where we were teaching them what bitcoin and crypto are and what’s happening in its underlying world. The outcome of these discussions was the Payment Services Act” (Ent-8). In terms of talent, we also found evidence indicating that smaller fintech startups face difficulty in retaining talent. One interviewee said, “when banks want to get their latest payments app built, they engage consulting firms like Accenture that will then go to win that contract by telling the bank that they’ve got many people with FinTech experience; they get those people by tearing out developers working in a fintech. The fintech sector is relatively young; that makes the ecosystem less capable of retaining [talent]” (Ent-4).

Further, our analysis revealed the role of governmental actions in supporting fintech innovators. A common view among interviewees was the leading role played by MAS in providing this support through active engagement with the fintech community. One entrepreneur said, “I discussed with MAS the possibility of running a thought leadership series on moving core banking onto the cloud, and they’re willing to facilitate a roundtable to have participants from the industry come together to discuss this” (Ent-7). Looking more closely at these engagements, another interviewee expressed the time-intensive nature of pursuing regulatory clarification: “The senior executives at MAS are very interested in what we’re doing, looking to push us forward and drive new ideas, but the reality of dealing with the regulators has been somewhat more step by step in nature, meeting different teams and departments within the regulatory authority” (Ent-6). We also found that regulators leverage other channels to engage with fintech startups; one of the interviewed incubator managers said that “MAS would connect with startups through incubators like ours; during the program phase, they would organize and attend different sessions, providing information on the offered infrastructure solutions or covering aspects like how to access regulatory sandboxes” (EC-12). Our findings also revealed the role of other governmental authorities in addition to MAS, as one interviewee noted: “A year after inception we started exploring development grants. We connected with Enterprise Singapore and received a grant from them for innovation and R&D. The agency also connected us with potential clients” (Ent-1).

For the fourth category, financial and knowledge capital transfer, the data provides insights into the role of VCs, business angels, and mentors. Some of the startups we interviewed shared their experiences in fundraising before fintech gained the attention of VCs. One entrepreneur said, “as we were trying to run a new kind of network in the capital market space in 2014, there wasn’t a lot of early-stage formalized VCs; business angels were the only ones present to back us with some equity funding. Then, within a year, we were able to start to tap into those early-stage VCs, and that ecosystem started to kick off. It’s firms like Wavemaker and Jungle Ventures who have backed us” (Ent-4). Another recurring view surfaced from incubation model actors with respect to connecting startups to VCs: “We have to be very convinced about the startup itself before we take it in or connect it to our own network in terms of funding possibilities. If we take the startup to a selected VC, they expect us to have done the required due diligence, that we’re convinced the startup has all the ingredients for possible success” (EC-13). A similar perspective was shared by one of the interviewed VCs, illuminating the interaction dynamics at the evaluation stage: “The due diligence process takes a bit longer because we want to ensure that we feel comfortable with the people establishing the startups; we want to spend some time to see how they behave, to know what their values are, and to learn whether their values are aligned with ours. How emotionally resilient are they? Do we think they’ve got the skills to be a successful CEO? And so on” (RP-16). From a mentoring perspective, many interviewees felt that VCs play a major role in providing active non-financial support by giving startups access effectively for free to their in-house expertise. At a strategic level, it was reported that VCs provide industry-specific knowledge, assist with go-to-market strategies, and help startups identify potential pitfalls in their value propositions. That said, startups may also access knowledge capital through traditional mentors that are commonly provided as part of an incubation model program or through support associations and platforms. One incubator manager said, “mentors enrich our capabilities and support offering; those are the experts that we don’t have internally. For example, we don’t have an investment banker as part of the core team, so this is something we can tap into through mentors. We reach out to our mentor networks that can then really give startups honest feedback and field insights on a voluntary basis; we don’t have any paid partnerships with mentors” (EC-12).

For the fifth category, horizontal networks, our evidence uncovered how ecosystem actors interact through a variety of events and channels. All interviewees applauded the efforts of the government and MAS in making Singapore’s financial market a global networking hub, with the SFF cited as an inclusive arena for connecting key stakeholders. Although this may be true, our interviewees also indicated the presence of abundant amateur actors and scammers in the ecosystem. In addition to the SFF, some interviewees reported that hackathons were a good avenue to meet VCs, accelerators, and like-minded entrepreneurs, while others said they connected with non-local clients through events held outside Singapore. One interviewee said, “I started building the InsurTech community here in Singapore and, with a few other people, founded and ran some of the earlier conferences in 2016 and 2017. I am also the founder and general secretary of an insurance association that has around 2,000 insurance buyers across Asia. Through that, I’m well networked into the community of insurers, brokers, and other technology firms” (Ent-6). As to virtual networking platforms, the common view of LinkedIn among entrepreneurs was captured by one founder: “LinkedIn is essentially my CRM [customer relationship management] system and one of my key tools for building my network. I currently have more than 10,000 global contacts that have been built up over my entire career, all of which would be financial services folks. If I need to reach out to a company, I’ll search the name of the company and there’s a very good chance that I already know someone at the management level, either directly or one degree away, which allows me to have the right conversations with the right people” (Ent-7). As evidence of how entrepreneurs leverage multiple roles in the ecosystem, another interviewee had the advantage of accessing clients and achieving credibility through affiliation with a fintech network: “AFTA [Asia Fintech Angels] provide me with opportunities to meet vetted fintechs, which helps me cut through the noise and work out who I should be talking with to provide my services” (RP-15). We also found evidence indicating that a VC firm mobilizes its mentoring position and co-location in an entrepreneurial hub to select investees, giving it the opportunity to interact closely with startups and determine whether there is something unique that can be scaled up. This happens by first observing the startups at an early stage, while being screened to access an accelerator program, and then interacting with them as mentors throughout acceleration that spans across three months.

4.1.2 Intermediation dynamics

As for mediating access to networks and critical resources, three categories emerged from the analyzed data describing the role of a selected actor or channel in connecting entrepreneurs within local ecosystems. These include (1) incubation models, (2) government solutions, and (3) platforms. Another prominent category revealed how (4) cross-border connections mediate access to non-local ecosystems.

For the first category, our findings showed that incubation models like business incubators and accelerators play an intermediary role among ecosystem actors and fintech entrepreneurs. Thus, directly connecting tenants to ecosystem actors, hosting networking events, or working with VCs that look for startups with a particular profile. A common view highlighted by incubation model actors was their ability to make the right connections, which saves entrepreneurs valuable time. One accelerator manager said, “being able to connect our tenants with the right person provides massive support, because nobody wants to take time off their busy schedule to find out who the right person is. We have corporate advisors working directly with startups to help with integration, because many corporates could be using legacy systems, providing technical support and industry insights. This saves a lot of trial and error for startups” (EC-11). The same interviewee was asked to provide an example of a use case reflecting this intermediary role: “We introduced one of our tenants to the government technical house GovTech, which helped solve bottlenecks in the technical process. Through our corporate networks, we have also connected that startup with multiple corporates, resulting in a six-digit deal. We also helped them raise $4–5 million by introducing them to our network of VCs” (EC-11). Hackathons emerged again as a networking mechanism, this time from the incubator perspective: “Our corporates demand hackathons because they give greater visibility to individuals or fintech startups unfamiliar to banks; they are a great way to recruit for the corporates” (EC-12). We also found, from the perspective of VCs, strong relations with incubation models to drive the top of the VC deal flow funnel, as one interviewee said: “We have built our own global networks of accelerators. We review many entrepreneurs from them and, when we like a very early-stage technology startup, we initiate direct discussions. And we now find it easy to do it without being present in that geography” (RP-17). Notably, this finding differs from our previously presented evidence showing how VCs benefit from their local presence in entrepreneurial hubs to interact with potential investees by highlighting how non-local ecosystem dynamics also allow VCs to exploit incubation model networks to find investees.

As to government-led solutions, the data revealed the intermediary role played by MAS, GovTech, and Enterprise Singapore in the fintech EE. One of the MAS infrastructure solutions, APIX, was mentioned by several interviewees, with two divergent discourses emerging. The first expressed the importance of this solution: “APIX helps FIs and startups to connect. It solves the problem of the long PoC process and asymmetric information that a startup faces when engaging with FIs” (RP-18). Although this may be true for some actors, a second view reflected reservations about APIX, as one entrepreneur put it: “I don’t think that signing up to it [APIX] is incredibly valuable because the ecosystem is small right now. And what this platform solves is essentially a discoverability issue. It’s not difficult to find companies now because of digital networks. Another issue is the quality ranking of application programming interfaces (APIs); it’s kind of arbitrary and opaque” (Ent-7). Our findings also revealed the common use of MyInfo, a GovTech data sharing service that simplifies the onboarding of new users. One interviewee said, “we were one of the early adopters of MyInfo, which allows individuals to easily do cross-border payments as part of our KYC [know-your-customer] process; once they log in, they can authorize the disclosure of their personal information to us” (Ent-2). The intermediary role of another agency, Enterprise Singapore, the startup support arm of the government, also became clear. According to one encounter related by an entrepreneur, Enterprise Singapore connected his startup to local hospitals and healthcare providers and directed it to access public funding opportunities.

Our evidence revealed the emergence of platforms as a third category that enables intermediation. Two main perspectives were expressed: the role of APIs as technology intermediary platforms and support organizations that provide a platform for networking. The proliferation of API technology arose in discussions of intermediary solutions, as one entrepreneur put it: “Previously, banks were one-stop shops providing various financial services through a special infrastructure including their own processors, data lakes, and servers. However, with the advent of API technology—which we call an un-bundling of the banks—what is now happening is the re-bundling of the banks through APIs; this way, we plug into a bank’s system to extract or access data through real-time algorithms. This can be achieved without having to build new infrastructures” (Ent-7). While the APIX platform presented in the above concept rests on the application of API technology to facilitate interaction among fintechs and FIs, it is also distinct by being a cross-border, government-led solution. Moreover, our findings show evidence of support associations acting as platform leaders, facilitating collaboration among entrepreneurs and ecosystem resource providers through a variety of solutions that includes providing access to VC databases exclusive to its members. One manager said, “we have a non-public database of 150 VCs based in Singapore; we segregate them by preferred startup stage for investment to perform good matching” (RP-18). Some interviewees even shared positive experiences in co-working spaces, which could be a conducive platform for networking and resource sharing. While these platforms may have enabled most fintech segments, our findings revealed that other types such as cryptocurrencies have not benefited from advantages like access to finance because they operated in an unregulated environment. Relatedly, one of the entrepreneurs indicated that the advent of ICOs as an alternative finance source changed this situation, giving crypto fintechs the opportunity to access capital while bypassing traditional intermediaries like VCs, support organizations, and FIs.

The fourth category, cross-border connections, reflects the mediating role of actors like VCs, Enterprise Singapore, and incubation models in connecting entrepreneurs to global networks. The most common view emerging from the data was that VCs play a substantial role in helping startups access networks and resources in other parts of the world, a theme expressed by both entrepreneurs and incubation model actors. For example, one entrepreneur said, “we are backed by Vertex Venture and Fullerton Financial holdings, who are well connected with the Ministry of Finance in Malaysia; they helped us access the regulatory jurisdiction by expediting the financial license application since we were one of the earliest cross-border payment fintechs” (Ent-2). The same founder also said that they were currently seeking VCs in Latin America to access regulatory and incumbent networks in that region. The government agency Enterprise Singapore was also commonly discussed among fintechs, with one entrepreneur noting that “we were able to obtain support from them [Enterprise Singapore], not just in the form of grants, but in the form of having physical people on the ground across the world, who guided us in terms of accounting access, legal support, office space; their support was there for us at a very early startup stage” (Ent-4). Another government initiative that arose was the SFF event, which serves as a channel to connect with non-local ecosystem networks like VCs and potential partners. We also found evidence indicating that incubation models leverage their global presence to provide local entrepreneurs with access to foreign networks. Along these lines, one VC shared his experience of using external networks to scout for investment projects: “There are two parts to this relationship: first, we access academics from the University of Waikato, University of Queensland, and La Trobe University for their cybersecurity expertise, to help us with technical due diligence. Second, 10% of our fund is allocated toward commercialization projects with university researchers who might be onto a good idea, which we identify through this relationship” (RP-16).

4.2 Cultural perspective

4.2.1 Ecosystem development dynamics

Two categories emerged from the cultural perspective: (1) ecosystem readiness and (2) openness to support.

For the first category, the empirical findings revealed two recurring views related to the preparedness of ecosystem actors. One perspective that emerged from entrepreneurs reflected the stage of fintech in retrospect, as one participant put it: “Early-stage conferences in 2014 and 2015 were very conceptual. There was a lot of talk on AI [artificial intelligence] with little to no action; nobody knew what we mean by this, what specific solution this is, what problem this is solving, and who the customers are. Fast forward to today; everyone feels a lot more confident that they could see where and how the innovation needs to happen and why it’s going to win or lose” (Ent-4). On the cryptocurrencies and blockchain side, it was reported that before 2017 only a few participants attended events and conferences; however, with rising bitcoin prices, that all changed. The presence of entrepreneurial role models as early drivers of the cryptocurrency and blockchain ecosystem is notable in this setting. Our findings indicate that only a handful of individuals were active in this segment prior to 2017, hosting workshops and conferences; one of these individuals is the founder and managing director of the cryptocurrency association in Singapore that has growing global importance. Further, we found evidence indicating that entrepreneurs played an important role in educating ecosystem actors including VCs, who at earlier stages were less convinced about the need for disruption, the identified problems and solutions, market size, and so on. This required layer of education was reported to be more crucial for fintechs operating in segments outside the digital payment space. Regarding this issue, one VC said, “many of the VC providers lack the necessary expertise in the cyber area to do a sufficiently thorough due diligence of the opportunities. They tend to be conservative and stay away. That’s a big factor in why there hasn’t been as much money flowing into cybersecurity startups” (RP-16). Beyond the problem of a potential lack of knowledge, another VC pointed out the issue of poor exit rates for over US$100 million in Singapore in comparison to established ecosystems like London or New York. According to the VC, not exiting at that threshold will make it difficult to justify an investment from an economic point of view. The second view, interestingly, draws on the experience of a non-local incubator who accessed the fintech ecosystem in Singapore to find that actual readiness deviates from external perceptions: “Before we decided to come to Singapore, we’d done our research and had built our network; Singapore looked more mature on the outside, but we soon learned that their digital infrastructure and mindset is not ready. Even though everybody speaks about fintech and they seem to know what they’re talking about, as soon as we have more in-depth discussions, we realize no, they are not at a point where we can apply our own model that we’ve created in Switzerland. A lot of the banks that we’ve encountered here still believe that they can pull it off on their own. If they have an innovation lab, they think that’s enough. The banks here have this very internal focus, which stops them from seeing the challenges that they are facing. Even when collaborating with startups, it’s on a very ad hoc basis and with an unstructured process” (EC-12). Importantly, this finding contrasts with the retrieved evidence from locally established incubation models who did not disclose similar concerns about the technical or cultural readiness of FIs.

As for the second category, openness to support emerged from our data to indicate a vibrant scene with ecosystem actors open to connecting and sharing their experiences. These views arose in different perspectives, including VCs and support organizations. For example, one VC said, “on a voluntary basis we would help very early-stage startups; for instance, we provided a female founder of a technology business with mentorship: just acting as professional coaches, bouncing ideas back and forth, suggesting ways to go about things” (RP-16). Another aspect that was mentioned is the presence of government-backed organizations like SG Innovate that organize talks that are free of charge. Even from the perspective of entrepreneurial actors, we found evidence that may indicate an openness to engage: “In our view, everything is interconnected, and the solution has to be holistic, and you’re not going to get that on your own. We engage our solution with many other players, whether they’re disruptors or those that are to be disrupted” (Ent-4). That said, our findings also indicated banks’ reluctance to collaborate with fintechs, though this view varies from country to another. For example, one of the cross-border payment firms still face resistance from incumbents: “Some banks think that by supporting fintech its putting risk on their whole operations and on their compliance; we do come across banking or FI partners that would suddenly cease operations” (Ent-2). Relatedly, we found that some fintech segments like cryptocurrency providers are unable to access normal banking services. One of the interviewees operating this type of fintech said, “it’s impossible to open a bank account to cover the normal operation of a business because banks are still being threatened by cryptocurrency projects” (Ent-8). Moreover, our findings revealed a support orientation favoring business-to-business (B2B) fintechs, from the perspective of both support organizations and VCs. One interviewee said, “we prefer B2B fintechs because these founders would usually have worked in a FI, have identified a particular problem area and have the deep domain knowledge that’s required to successfully navigate the entire market” (EC-10). One VC added, “we find it easier to define the conditions for success in B2B providers because they tend not to be a winner-take-all approach” (RP-17). Along the lines of providing advantages to selected fintech businesses, our findings also reveal differential willingness to support fintechs practicing regulatory arbitrage, non-employment of local talent, or compliance with other policies, all of which limit opportunities to access local ecosystem resources. These findings are elaborated in our discussion of regulatory dynamics.

4.2.2 Regulatory dynamics

As to regulatory dynamics, our findings fell into two categories, predominantly capturing entrepreneurial actors’ perspectives: (1) attitude toward regulators and (2) regulatory contributions.

For the first category, our empirical evidence revealed views about regulators that emerged largely from foreign entrepreneurs based in Singapore, one of whom said, “I am convinced that every fintech will say the same thing: the less interaction you have with the regulator, the better. It is unlikely they understand exactly what it is you’re doing. Startups are likely to be faced with a whole bunch of regulation, interpretation, and case law based on businesses that have existed a long time before theirs did and based on an ecosystem which looked completely different. For example, the ease of dissemination of information globally via a platform like ours is not addressed in most financial regulation” (Ent-4). The absence of uniformity between regulators was a consistent pattern; these views concur with the highlighted evidence on the role of governmental actions in supporting fintech innovators, though from the relational perspective. For example, there is misalignment between the C-level executives who strongly advocate for fintech and the other regulatory officers with whom startups will interact with once they approach MAS: “[The officers] don’t care about any of that stuff that those 20 people talk about. They’ve got a lot of paperwork to fill in, rules and regulations to follow, putting you in the wrong boxes, trying to make you apply for different things” (Ent-4). Talking about the same issue, another interviewee said, “it took me 15 months to get into the regulatory sandbox. It was still a time-consuming process, and I know the senior management at MAS would like to make that faster” (Ent-6). Another important point is that certain areas are more regulated than others, which may create prohibitively high hurdles, as one interviewee put it: “If you move into areas like wealth or asset management, it becomes very expensive: one thing is paying the license fee, but you also need to have two employees who are Singaporean with at least five years of experience” (Ent-5). The same entrepreneur added that fundraising in these areas is difficult, as investors would normally want to see at least some revenues generated prior to making any investments, and it is impossible to generate revenues without a license. When asked about how to overcome regulatory barriers, entrepreneurs emphasized a pragmatic approach to dodge regulators, including the creation of safe regulatory covers and careful selection of the regulatory jurisdiction in which to operate. For example, one entrepreneur said, “we try to do international arbitrage; getting an asset management license in Switzerland is much easier than in Singapore, despite the fact that we are sitting here” (Ent-5). More interestingly, our findings indicate that foreigners establishing a business need to have an inside director who is a Singaporean citizen or permanent resident: “If you found a startup company and you tried to do it bootstrapped, you will not be able to get a work permit for yourself; this can be a showstopper for incorporating in Singapore. That’s why we incorporated it in London. Now, we are looking to enter an accelerator program to be in a better position to raise capital; however, we may not qualify as we are not incorporated here” (Ent-5). Another possible implication of this issue emerged from a VC: “We’ve not been able to access any of the support offered by the development arm for fund managers because we’re not Singaporean enough, even though we are incorporated here, which makes us ineligible for many other support programs” (RP-16).

As for the second category, regulatory contributions were found to have a positive impact on a culture conducive to entrepreneurial actors and the fintech EE more broadly. The regulator said that MAS, unlike other regulatory authorities, has a market development objective and thus has a dual role focused on both regulation and innovation. Recent contributions such as the Payments Service Act surfaced among interviewees operating in the cryptocurrency space, as highlighted under resource recycling in regard to entrepreneur–regulator collaboration during this process of regulatory change. This finding, however, indicates how such regulatory intervention is perceived by entrepreneurial actors; one entrepreneur said that “the new act is a big leap forward because new regulatory frameworks state what you can do under which circumstances” (Ent-5). Another recurring contribution was the regulatory sandbox; a primary benefit of this mechanism was allowing participants to waive a large investment in financial licenses until the end of their exemption periods (if they opt to proceed). One VC told us that “the sandbox provides a safe harbor to launch and allows us to de-risk some of the more innovative financial products and be able to launch them without necessarily fearing that the regulator will wake up one day and pull the plug” (RP-14). Relatedly, one of the entrepreneurs criticized the role of regulatory sandboxes in driving innovation, stating that regulators spontaneously launched sandboxes overlooking how they should operate: “I don't think they did it well enough. But then, I wouldn't expect a regulator to do that, because regulators aren't innovators. They're policy people” (Ent-7). That said, we found evidence of supportive top-level regulators demonstrating commitment to improving financial markets by confronting incumbents. One entrepreneur said, “a MAS fintech officer recently posted, ‘No more PoC for free,’ which reflects what startups very often have to deal with when engaging with banks” (Ent-5).

5 Discussion and implications

In addition to the findings presented above, we discuss a few important observations from which our theoretical propositions are derived; we then devote a section to present the main barriers ecosystem actors face, followed by the implications of this study.

Given that fintech is an emerging phenomenon, some unregulated segments like blockchain and cryptocurrencies face unequal acceptance from ecosystem actors like banks, VCs, and regulators. Under these ecosystem conditions, our empirical evidence indicates that these institutional voids give rise to the formation of a new ecosystem spearheaded by entrepreneurial role models. In turn, this enables novel fintech segments to grow, as indicated by one of the interviewed early affiliates in the blockchain and cryptocurrency community. In line with the previous EE literature (e.g., Goswami et al., 2018; Kuratko et al., 2017), it may be deduced that the entrepreneurial commitment of earlier fintech affiliates creates value in EEs. Such value creation not only constitute of helping newcomers to access existing resources but also and more importantly by acting as catalysts to establish the key building blocks of an ecosystem. This may include a support association that provides mentorship and acts as an intermediary between ecosystem actors like regulators and FIs. Thus, allowing fintech entrants to exploit opportunities and contribute to system-level outcomes such as business model innovations (Autio et al., 2018; Cao & Shi, 2020). We can further postulate that the presence of institutional voids causes early entrepreneurial affiliates in novel fintech segments to create a support ecosystem, thus accelerating entrepreneurial identification and exploitation of opportunities in fintech EEs. We therefore suggest that.

-

P1: Institutional voids precipitate first-comer members to create supportive ecosystems, facilitating efficient access to and exploitation of resources for forth comer startups.

Another important observation is that entrepreneurs play a central role in shaping future fintech regulations through their interactions with regulators. For example, the Payment Services Act was reported to have been co-created with entrepreneurial actors. While we recognize that the important role of the government in Singapore’s fintech EE goes beyond traditional support like financing R&D and controlling market demand (Doblinger et al., 2019), our findings lead us to postulate the existence of a relational rather than a hierarchical governance model (see Colombelli et al., 2019 for an overview). As such, entrepreneurs drive the interaction dynamics of collaboration. This view is also supported by the presence of different social clusters contingent on the fintech segment, with a specialized support infrastructure built around them. For example, we found that blockchain and cryptocurrency startups have support associations and incubation models offering specialized services, which confirms the fundamental feature of EEs as smaller ecosystems located inside larger ones (Brown & Mason, 2017). While this finding is well supported in the literature, our study confirms the presence of nested geographies in digitalized industries. Our findings further demonstrate the hierarchical governance of the government through MAS, this time in regard to intermediary solutions; it functions as a centralized infrastructure solution provider to govern the intermediary dynamics of collaborationFootnote 6 between fintechs and incumbents. While this may be expected, given the fundamental role of regulators in securing financial markets against systemic risks, our findings suggest that MAS has incentivized banks and FIs to open their own innovation labs in the past 2 years. Resultantly, indicating that almost all banks in Singapore now have their own labs. Similarly, intermediary platforms like APIX were established to promote collaboration among incumbents and newcomers. These efforts represent the dual role of this regulator, which is focused on both regulation and innovation. However, this orientation may disfavor business-to-consumer (B2C) fintechs in the EE and thus weaken competition in financial markets, which is currently an unexplored topic in the literature; recent contributions have focused on collaboration among—rather than competition between—banks and fintechs (Hornuf et al., 2020). Based on the above discussion, we suggest the following propositions:

-

P2a: Entrepreneurs drive the interaction dynamics of collaboration in fintech EEs, contributing positively to the co-creation of fintech-friendly regulations and support infrastructures.

-

P2b: The dual role of the regulator ensures the governance of intermediary dynamics between ecosystem actors, affecting the development of fintech innovations.

Another heavily debated aspect of EE research is spatial boundedness; common explanations of EEs propose the need for close geographic proximity with ecosystem actors to foster localized interactions and knowledge flow (Brown & Mason, 2017). However, digitalization has been argued to reduce such spatial contingencies (Autio et al., 2018). Our findings confirm that founders are able to access new markets and opportunities remotely, though this is often found to be facilitated by intermediaries like VCs and government agencies or platforms like APIs. Similarly, our findings reveal that VCs not only play the role of financial and knowledge capital providers but also mediate access to non-local networks, including regulatory authorities. In so doing, they may help fintechs overcome a primary cause of failure by successfully deploying their solutions beyond national boundaries (Mention, 2020). This latter function of VCs is merely explored in the existing management literature (Clayton et al., 2018) and merits much more detailed study. Notably, our findings also indicate that VCs discover potential investees without having to be present in the same geography, thanks to digitalization and connectedness to local actors like incubators and accelerators. On this basis, it may be deduced that.

-

P3: Digitalization and the presence of localized intermediary actors positively affect entrepreneurial actors’ accessibility to non-local ecosystems, which drives opportunity exploitation.

Moreover, foreign entrepreneurs residing in Singapore shared their view of regulators, emphasizing a bureaucratic and entrepreneurial-unfriendly system, due to factors like unfavorable labor market regulations and fear of incurring high compliance costs, which may drive entrepreneurs to other jurisdictions. Such regulatory arbitrage emerged from our evidence and is consistent with the literature (Cumming & Schwienbacher, 2018). These findings may also be associated with studies indicating that jurisdictions with stronger regulatory enforcement have lower VC investments in fintechs (e.g., Cumming & Schwienbacher, 2018). While our findings cannot confirm a relationship between investment levels and regulatory enforcement in Singapore, they do indicate another reason for lower investments; namely, the lack of VCs’ technical and industry knowledge. As a result, VCs ability to conduct appropriate due diligence is affected, especially in novel fintech segments. This perspective may contradict earlier findings in the literature that acknowledge VCs for their investment decision-making abilities (e.g., Nahata, 2008). However, a closer look at the literature (e.g., Cumming & Schwienbacher, 2018) reveals that VCs operating in smaller financial centers with fewer exit opportunities are more likely to be inexperienced and as such may not be capable of conducting rigorous due diligence. We argue that this is not necessarily the case for Singapore, given its strong fintech presence.Footnote 7 Other possible explanations are the existence of immature VCs during boom periods (Cumming & Schwienbacher, 2018); however, this would explain higher investment rates rather than the contrary. Nevertheless, it is still unclear why VCs may lack the required knowledge to perform due diligence and then invest in novel fintech segments; this is a promising avenue for future research. More importantly, our findings also indicated the role of the fintech EE in moderating VCs’ possible lack of critical knowledge. Specifically, we found evidence of how a VC firm mobilizes their mentoring position and co-location in an accelerator to interact with potential investment candidates over a longer period of time to assess the characteristics and features of the entrepreneurial team, along with the solution. In this regard, the same VC also reported utilizing multiple non-local ecosystem university institutions to conduct technical due diligence. We therefore suggest that.

-

P4: VCs’ lack of industry and technical knowledge of novel fintech segments can be compensated for through co-location to enable interaction with potential investees and collaboration with ecosystem actors to assist with due diligence.