Abstract

Some scholars assert that entrepreneurship has attained “considerable” legitimacy. Others assert that it “is still fighting” for complete acceptance. This study explores the question, extrapolating from studies of an “elite effect” in which the publications of the highest ranked schools differ from other research-intensive schools. The most elite business schools in the USA, but not the UK, are found to allocate significantly more publications to mathematically sophisticated “analytical” fields such as economics and finance, rather than entrepreneurship and other “managerial” fields. The US elites do not look down upon entrepreneurship as such. They look down upon journals that lack high mathematics content. Leading entrepreneurship journals, except Small Business Economics Journal (SBEJ), are particularly lacking. The conclusion argues that SBEJ can help the field’s legitimacy, but that other journals should not imitate analytical paradigms.

Plain English Summary Academic snobs shun entrepreneurship journals. A goal for snobs is to exhibit superiority over others. For business professors, one way to do this is with mathematically sophisticated, analytical publications. Entrepreneurship journals, Small Business Economics excepted, do this relatively infrequently. These journals focus on the lives, activities, and challenges of diverse entrepreneurs. In the USA, the most elite business schools, compared with not-quite elite business schools, allocate significantly more of their articles to the journals of analytical fields such as economics, and fewer to entrepreneurship journals. This pattern is not found in the UK, where elites may have other ways to signal superiority. These elites, who accommodate entrepreneurship researchers, could pioneer with outputs of both relevance and scholarly quality, through collaboration between their practice-based and research-based professors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A panel of editors for entrepreneurship journals drew an attentive audience. Professor Ian MacMillan, founding editor of the Journal of Business Venturing (JBV), introduced his then-start-up journal. To explain its novelty, he proclaimed it as “double-blind reviewed.” To this, Professor James Thompson, editor of the Journal of Small Business Management (JSBM), objected that his journal, too, was double-blind reviewed. However, MacMillan was merely being tactful. He avoided stating the obvious: JBV aimed to be the first entrepreneurship journal for research of the highest quality. At the time (1985), the field offered few dedicated options for scholarly publication. No entrepreneurship journals were covered by the Web of Science (i.e., Social Sciences Citation Index). The American Journal of Small Business had yet to morph into Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, Small Business Economics, and Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal had yet to appear. The International Small Business Journal was not yet professionally managed. Moreover, guidelines for authors in JSBM showed that its goals were practical, not scholarly. “All manuscripts… should be prepared with business readers… in mind. Highly sophisticated statistical or mathematical analyses and strictly theoretical academic discussions should be avoided” (Anonymous, 1985, unpaginated).Footnote 1

James Thomson was a professor at West Virginia University, a research-focused but non-elite institution. By contrast, by establishing “entrepreneurship as an academic subject at a renowned business school such as Wharton School of Business,” MacMillan brought “legitimacy to the field” (Landström, 2010, p. 295). This study explores Landström’s claim of legitimacy. Specifically, it explores the academic legitimacy of its dedicated journals. Academic legitimacy is not an ivory tower matter. It is required for a scholarly field to sustain and reproduce itself. It is required for supervising doctoral students, adding or replacing tenure-track faculty, and tenuring promising scholars (Hambrick & Chen, 2008; March, 2018).

A dozen years ago and more, the legitimacy of entrepreneurship as an academic field was described as incomplete, “marginal,” and “partial” (Katz, 2008, pp. 551, 562; Kuratko, 2005, p. 587). Compared with better-established fields, such as finance, it emphasized “relevance for external stakeholders” at the expense of a dominant scholarly paradigm (Audretsch et al., 2015) with “common theoretical frameworks” (Landström & Harirchi, 2019, p. 525). These are required for academic legitimacy (Abbott, 2001, p. 145). Recently, however, Landström and Harirchi found evidence of a transformation of entrepreneurship research, thanks to “robust and theory-based quantitative studies [using] sophisticated statistical techniques,” and concluded that “over the last decade, entrepreneurship as a scholarly field has… gained increased academic legitimacy” (Landström & Harirchi, 2019, p. 507). Similarly, Shepherd—a well-placed observer—proclaimed that “by every measure the field now enjoys considerable academic acceptance and legitimacy as a scholarly discipline” (2015, p. 419). According to Welter et al. (2017), the field has become “extraordinarily legitimate.” By contrast, Wood (2020) argued that “entrepreneurship… is still fighting for universal recognition as a fully legitimated academic field” (p. 1).

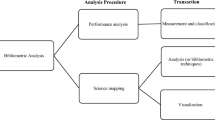

This study was inspired by my experiences on the faculties of four North American business schools. I observed the high value placed on methodological sophistication. This study was also inspired by findings and omissions in prior research on the “elite effect,” whereby publications from elite institutions differ favorably from nearly elite institutions. In this study, I try to fill gaps in this research. Using bibliometric methods, I am able to specify, and plausibly explain, the limits to legitimacy still remaining for entrepreneurship journals.

One of the gaps in previous work is comparison of elite effects across national systems. Another gap is a narrow focus on numbers of articles (Joy, 2006), numbers of citations to journals of publication (Chan & Liano, 2009) and (less often) citations to the scholars’ articles (Ahn et al., 2014). Previous work on the elite effect has not evaluated the prestige of the journals of publication. Furthermore, prior research on the elite effect in publishing did not ask whether scholars in the highest ranked schools differ on types of outcomes. For example, do they allocate their efforts to different disciplines or different types of disciplines? The elite effect has been found only when the highest ranked agents score higher than the next highest ranked agents on the same outcome. For example, Oyer and Schaefer (2019) found that graduates of the first through tenth ranked law schools earned “considerably” more than graduates of law schools ranked 11 through 20.

After this introduction, section 2 considers the prior research. Section 3 presents the study’s five research questions, which include a comparison between publication patterns in the UK and the USA. Section 4 explains the method and robustness checks. The method is bibliometric. Section 5 presents the results, including a post hoc exploration. Section 6, on the discussion and conclusions, reflects on implications for scholars in the entrepreneurship field, and for people who influence publications, such as journal editors and deans.

2 2Prior literature

2.1 Rankings of entrepreneurship journals

Optimism about legitimacy, by Shepherd, and Landström and Harirchi is supported by data about entrepreneurship journals, as McMullen (2019) reports. Field journals reflect the status of the field and attract, or fail to attract, submissions from capable scholars (Hambrick & Chen, 2008; Stewart & Miner, 2011; Wood, 2020). Those in entrepreneurship do very well in major listings. In the UK’s Association of Business School (ABS) list, ET&P and JBV rank at A*, the highest level, while SBE and SEJ rank at A. In the Australian Business Dean’s Council list, ET&P and JBV also rank at A*, the highest level, while ISBJ, JSBM, SBE, SEJ, and Entrepreneurship and Regional Development (ERD) rank at A. ET&P, JBV, and SEJ are included in the influential Financial Times 50 (FT50) list. Table 1 lists these entrepreneurship journals, except ERD, and the 19 other FT50 journals in the sample for this study. Leading entrepreneurship journals have very high impact factors. We can see that the widely noted 2-year impact factor (JIF) for ET&P, JBV, and SEJ has risen dramatically, by 4.23 times, over the past decade, ranking above almost all the journals in the list, including the finance journals.

2.2 Impact factors compared with measures of prestige

Table 1 also shows a less hopeful sign. Increased impact factors have not been matched by similar increases in SJR scores. Impact factors measure the “popularity” of journals, whereas Scimago SJR scores in Scopus (and Eigenfactor scores in Web of Science) measure “prestige.” Prestige derives from citations from highly regarded journals, as compared with popularity, which derives from all journals regardless of quality (Bollen et al., 2006; Franceschet, 2010). Impact factors are poor measures of legitimacy, particularly as signs of recognition from leading scholars, who often work in leading universities. As Abbott (2001), p. 141) observed, legitimacy is valued most highly “in elite universities” (Abbott, 2001, p. 141). Perhaps the reason that entrepreneurship’s legitimacy has been incomplete, as Katz, Kuratko, and Wood believed, is because it has not reached the highest ranks of schools.

Due to normative and “cultural-cognitive” isomorphic pressures (Scott & Biag, 2016, pp. 37–38), elite universities and publications by their faculty are the models imitated by a wide range of schools (Harman & Wood, 1990; Siltaoja et al., 2019). Despite countervailing efforts to achieve distinctiveness (Vakkayil & Chatterjee, 2017), isomorphic pressures create “an ongoing homogenization in terms of publication and productivity among the top-500 universities in the world” (Hallfman & Leydesdorff, 2010, p. 69). The model that is emulated is that of the most illustrious universities, such as Harvard and Chicago (Medoff, 2006). The influence of elite universities, and their heightened sensitivity to academic prestige, focus my efforts in this study on the publication patterns of elite compared with not-quite-elite business schools.

2.3 Elite effects

“The rich are not like us,” offered F. Scott Fitzgerald. Ernest Hemingway replied, “yes, they have more money” (Bernard, 1965: 14). Was either of them right, metaphorically, about publications from elite business schools? Do elite schools differ in publications from non-elite, research-intensive schools? If so, are the differences merely quantitative, as Hemingway might have expected? Or are they also qualitative, as Fitzgerald might have expected? If there are qualitative differences, do these reflect differences in attention to management education or, instead, to scholarly prestige? Prior studies have demonstrated an “elite effect” of university affiliation on publications. Compared with scholars in other major research universities, those affiliated with the highest ranked universities produce larger numbers of journal articles (Joy, 2006) that are more highly cited (Ahn et al., 2014) and published in journals with higher citations (Chan & Liano, 2009). Similarly, scholars in the best-resourced universities produce the most scientific output (Lepori et al., 2019). Furthermore, this effect “has increased… in the last three decades” (Kim et al., 2009 p. 355).

3 Research questions

3.1 Questions, not hypotheses

Hypothesizing in this study runs the risk of HARKing—hypothesizing after the results are known (Kerr, 1998). Legitimate hypothesizing is not feasible for two reasons. One is the complexity of uncontrolled factors affecting the outcome. The other is the lack of theory to motivate hypotheses. The literature offers observations about changes in entrepreneurial scholarship, but not a theory of changes in its legitimacy. We also lack theory from the “elite effect” studies, which are purely descriptive. One way to demonstrate this point is the approach they take to the concept of “elite.” They adopt an uncritical, common-sense meaning, elsewhere defined as “superiority in meaningful measures” (Hartmann, 2007, p. 2); in this case, rankings. This meaning is assumed in much other work on elite education, such as Kim et al. (2009) and Oyer and Schaefer (2019). I follow this common practice in order to explore the top-ranked schools, but recognize that the meanings of “elite,” and the related expression “world class,” have been socially constructed (Siltaoja et al., 2019; Wedlin, 2006) and should be interpreted in its social context.

3.2 Five questions

The first question sets the context for entrepreneurship journals, as representatives of managerial, rather than analytical, fields. Do elite effects exist, whether positive or negative, for analytical, managerial, and entrepreneurship journals? Elite effects are positive if elites allocate significantly more to the type of journal in question, and vice versa. Because we lack strong reasons to classify the journals by category, these effects will be examined journal-by-journal.

Second, do elite effects, should they exist, improve for entrepreneurship journals over the prior decade? For example, is there a negative elite effect in the first period but a neutral effect in the second period? Is there a neutral effect in the first period and a positive effect in the second period? The third question is similar. Does the allocations of publications to entrepreneurship journals increase, for each category of school, over the decade? Fourth, do the results apply only to entrepreneurship journals in the FT50 list, or do they apply to other leading, but non-FT50 entrepreneurship journals?

3.3 US–UK comparisons

The fifth question is, do the allocations of publications to entrepreneurship journals differ between the USA and the UK? This study examines possible elite effects within the same nation, because higher education systems differ across nations (Pezzoni et al., 2012). I examine publications in business schools in the USA and the UK, which differ in their environments for entrepreneurship research (Aldrich, 2012). These are the largest and second largest countries for publications in scholarly business journals (Chan et al., 2007). They are currently the only systems of business schools large enough to examine elite effects, which compare several elites with larger numbers of major research business schools. (This will no doubt change.) They are also similar in national cultures (Ronen & Shenkar, 2013). Nonetheless, business schools in the two countries are different enough that their publication patterns might differ (Lampel, 2011). Üsdiken (2014) found that UK business school scholarship has remained less influenced by US styles of research than have other countries. Major UK business schools are young, as Cambridge launched its MBA in 1991 and Oxford in 1996. Other elite UK business schools at that time were only about 40 years old (Anderson, 2006: Chap. 4). Another difference is that elite business schools in the USA are all housed in prestigious universities, but this is not the case in the UK, where Cranfield, widely seen as an elite MBA school, is part of a major engineering university, but not an elite institution. The same could also be claimed for Cass, part of City, University of London.

American universities are highly diverse, UK universities less so (Rowlands, 2017; Scott & Biag, 2016). The USA has major private research universities, the UK does not (Arum, Gamoran, and Shavit, 2007). Diversity in the USA has meant that “institutional rivalry has always marked American higher education to a greater extent than in other countries” (Bok, 2003: 14). However, since the mid-1980s, the UK system has experienced increasing rivalry for discretionary funding as state support declined (Anderson, 2006, Chap. 11; Foskett, 2011). UK business schools experienced an increasing concern for their ranking and chances for “global elite” status, and responded with managerialism and marketization.

4 Method

4.1 Sample of business schools

The sample of universities for the USA is the 115 universities with the highest levels of research activity in the Carnegie Foundation classification, covering the closest (2015) academic year. “Elites” are not compared with universities that are clearly inferior. Eight universities (such as Brown, Princeton, and Cal Tech) that lack business schools were dropped, as were schools with research masters but not MBAs (e.g., LSE and UCL). For the UK, the Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) and Times Higher Education (THE) rankings were used to determine how many universities are equivalent in global ranking to the 115 US universities. Nine schools were dropped from the sample for fewer than five publications in the sample, leaving 102 US schools and 38 UK schools. Only main campuses are counted, and only the graduate (MBA) school if distinct from the undergraduate school (as with Virginia).

4.2 Delineating the elite MBA institutions

To differentiate between elite and less elite, or “research business schools,” the MBA rankings are for 2016, as an estimate of the lead times from research concept to publication. The overall measure of 2016 MBA rankings in Poets & Quants was used. It is a weighted average of rankings from Business Week, Financial Times, Forbes, The Economist, and U.S. News for the USA and all but the latter for the UK. Rankings are contestable; none are definitive. However, studies in cognate fields (public administration and sociology) suggest that ranking are quite stable, especially towards the top (Fowles et al., 2016), and the delineation between “elite” and non-elite departments is enduring (Weakliem et al., 2012). Because rankings of the MBA programs are the basis of delineation, the term “elite” refers to that basis only.

Rankings do not provide unequivocal boundaries between elite and research schools. Exclusivity is a requirement for elite status (Leibenstein, 1950), yet a larger set of elite universities provides a conservative way to test elite effects. Thus, the sample was split in two ways. Based on relatively large discrepancies in rankings, 14 US business schools were classed as the “stringent” elite: Berkeley, Chicago, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Duke, Harvard, Michigan, MIT, Northwestern, Pennsylvania, Stanford, Virginia, and Yale. Seven UK business schools were classed as “stringently” elite: Cambridge, Cranfield, Lancaster, LBS, Manchester, Oxford, and Warwick. Next, the samples were split into quartiles. This created a US “quartile elite” that adds Carnegie Mellon, Emory, Indiana, North Carolina, Notre Dame, N.Y.U., Rice, Texas, UCLA, and Washington. By the same token, Cass, Durham, Imperial, and Strathclyde were added to form the UK quartile elite.

4.3 Sample of journals

Table 1 showed the sample of journals. It was designed to compare the allocation of publication by elite with non-elite business schools, across analytical fields and those that (in the critics’ view) should be more, not less, developed. Reviewing the critical literature and searching in ProQuest yields six scholarly fields that are widely promoted as needing more attention: entrepreneurship and innovation (Spender, 2014), ethics and social responsibility (Dyllick, 2015), information systems (Thomas et al., 2013), international management (Jain & Stopford, 2011), operations (Lambert & Enz, 2015), and “soft skills” and organizational behavior (Pfeffer & Fong, 2002). The six fields were broadly defined.

To control for one influence on the allocation of publications across journals, I sampled only those included in the Financial Times 50 (FT50) list. This is only one ranking list, but an influential one. I selected 22 journals for the managerial fields, and nine that cover analytical fields. Based on SJR scores, I added the three most prestigious non-FT50 entrepreneurship journals, International Small Business Journal, Journal of Small Business Management, and Small Business Economics, in order to compare them with the three FT50 journals. I excluded three important analytical journals. Because we wish to see the effects of factors influencing business schools, and the rankings to delineate elites are based on business schools, not universities, I counted only authors with at least a joint affiliation in a business school. A consequence of this decision was omitting three FT50 economics journals. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Journal of Political Economy, and Review of Economic Studies seldom note affiliations below the university level.

4.4 Measures and analysis

Many disciplines have recently discouraged the use of p values in reporting findings (e.g., Gardner & Altman, 1986, in medicine). I follow the advice of Gardner and Altman (1986), Meyer et al. (2017), and Schwab (2015), presenting the results with 95%confidence intervals as estimates of differences between classes of schools, with an estimate of effect size; in this case, Glass’ Δ. Probabilities are interpreted as follows: disjoint confidence intervals mean that the samples differ, P < 0.05. Overlapping confidence intervals mean there is no difference between the samples, P > 0.05. Effect sizes are interpreted with the “conventional” heuristic of 0.2 standard deviations meaning “small,” 0.5 meaning “medium,” and 0.8 meaning “large” (Schäfer & Schwarz, 2019, for limitations of heuristics absent the research context). Confidence intervals are presented in tables rather than graphs. These results are complex as it is; graphs would be overwhelming. Therefore, bolding and underlining in the tables are used to draw attention to significant results. The tables provide all details for interested readers. Fortunately, the results, reported below, are straightforward.

The SJR was used as the measure for journal prestige because it is size-independent and draws from a larger sample of publications than the Eigenfactor score (González-Pereira et al., 2010). One other judgment was needed. Should authorships be discounted by numbers of co-authors? Studies of scholarly output do so (Abramo et al., 2013) This is appropriate for such a purpose, even though “universities generally do not fully discount… in promotion, tenure, and salary decisions” (Hollis, 2001, p. 526) However, discounting is not appropriate when the research question is the relative association of types of universities to scholarly fields. Unlike most bibliometric studies, this study does not compare authors or journals; it compares business schools. Thus, the unit of observation is the undiscounted authorship. Authorships are the unit of measurement as they reflect allocation of scholarly work, regardless of number of authors.

4.5 Two robustness checks

Two robustness checks examine my categorization of the 22 journals into analytic and managerial categories. The first correlates journals based on shared school authorships. This required an adjacency matrix representing the number of school authorships shared by each journal. It was created with the sum of the cross-minimums method in UCINET6, transforming a two mode matrix of schools-by-journals to a one mode matrix of journals mapped onto journals (Borgatti et al., 2002). This method is used with valued, non-negative data, as in this study (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005, Chap. 6). I used Johnson’s hierarchical method to cluster a correlation matrix of the adjacency matrix. The clustering, shown in Fig. 1, is similar to the categorization of journals used in this study, but there are differences. As expected, the major disjunction, at r = 0.485, is between all nine of the analytical journals and all six of the entrepreneurship journals. The entrepreneurship journals cluster together at a minimum correlation of 0.793. The strongest cluster among them, at 0.881, is ET&P, JBV, and JSBM. However, only four other managerial journals cluster with the entrepreneurship journals: Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of International Business Studies, Journal of Operations Management, and Research Policy. An egregious misclassification is OBHDP, with its 0.956 correlation with finance and OR journals.

Clustering of journals by business school of authorship. Johnson’s hierarchical method, using UCINET 6 (Borgatti et al., 2002) for transforming to a single mode matrix (sum of minimums method), creating a correlation matrix, and clustering. Figures in the leftmost column are Pearson’s r

A second check is counting the number of articles with Greek mathematical letters. This required a list of such letters and an iterative process to see which such letters are in fact used in the sample. I did not use α, β, μ, or σ, because they are widely used in statistics. I used 17 letters: Γ, γ, Δ, δ, ε, ζ, Θ, θ, Λ, λ, Σ, Φ, φ, Ψ, ψ, Ω, and ω. As a more discriminating set, I also used Θ, θ, Λ, and λ.Footnote 2 Although these sets have only face validity, they served to discriminate amongst the journals, as shown in Table 9. Journals classed as “analytical” have much higher percentages of articles with these letters. The entrepreneurship journals, except SBE, have especially low percentages. These results help explain the relatively low clustering of JFQA with the other finance journals, but leave unexplained the results for OBHDP.

5 Results

5.1 Elite effects: US schools

Question 1 asked whether elite effects exist, either positive or negative, for analytical, managerial, and entrepreneurship journals. Results are reported in Table 2. For each time period there are nine analytical journals and two delineations of elites, and thus 18 possible elite effects (Table 2). With US schools in 2008–2009, we find 10 such effects, all positive, with elites allocating significantly more of their publications to these analytical journals than do the major research business schools. Effect sizes are large in six and medium in two of the cases. With US schools in 2018–2019, we find 13 elite effects, all positive, with 11 having large effect sizes and two with medium effect sizes. Thus, we see a strong orientation among elite US schools in favor of analytical journals.

Compared with major research business schools, US elites publish more in analytical journals, and correspondingly less in managerial journals. Out of 20 possible elite effects for the latter journals, eight are negative for 2008–2009 and 13 are negative for 2018–2019 (Table 3). Effect sizes are small in 10 cases and medium in eight. However, the later period also saw one positive elite effect (for OBHDP), which had the only large effect size. Results are similar for the entrepreneurship journals, which could be classified as managerial. Out of 12 possible elite effects, five are negative for 2008–2009 and six are negative for 2018–2019, with five small and one medium effect sizes (Table 4). This is the flip side of the preference for US elites to publish in relatively analytical, mathematically intense journals.

5.2 Elite effects: UK schools

Elite effects in UK business schools do not show the bias towards analytical journals that we find for elite US schools. UK schools show fewer elite effects (Tables 5, 6, and 7). With analytical journals, in both periods, there are four elite effects, all positive with large effect sizes. In both periods, the elites also allocate more publications to the Journal of Finance than research schools, with a large effect size, but with overlapping confidence intervals.Footnote 3 With managerial journals, in both periods, there are two elite effects for the Journal of Business Ethics, both negative and with large effect sizes. For entrepreneurship journals, there are no elite effects in the second period, and one negative effect for ISBJ, with a medium effect size, in the first period.

5.3 Change over the decade

Question 2 asked, do elite effects improve for entrepreneurship journals over the decade? For example, is there a negative elite effect in the first period but a neutral effect in the second period? Is there a neutral effect in the first period and a positive effect in the second period? In only two cases does an elite effect change, but in each case for the worse. For the US stringent elite, JBV has a neutral elite effect in the first period and a negative effect in the second. For the UK stringent elite, ISBJ has a neutral elite effect in the first period and a negative effect in the second. Question 3 asked whether allocations to entrepreneurship journals increased, in any category of school. Here, we see one sign of change, and it is an improvement. The allocation to JSBM significantly increased among the UK research schools. However, the pattern is stasis over the decade, contrary to the optimistic view of Landström and Harirchi (2019).

5.4 Other differences in allocations of publications

Question 4 asked if the results apply only to entrepreneurship journals in the FT50 list, or also to other leading, but non-FT50 entrepreneurship journals. US elites appear to prioritize FT50 journals, but we cannot conclude that the FT50 entrepreneurship journals receive more elite attention than leading non-FT50 journals (ISBJ, JSBM, and SBE). For this comparison, there are 54 journal dyads (three FT50 journals paired with three non-FT50 journals, three categories of schools, and two time periods). In 38 dyads, the differences are not significant. In five cases, the FT50 journals receive significantly more allocations. All of these apply to US research schools. In 11 cases, the non-FT50 journals receive more than the FT50 journals, in all cases with UK schools. Three cases apply to quartile elites and the other eight to research schools.Footnote 4

Question 5 asked if the allocation of publications to entrepreneurship journals differs between the USA and the UK. As the differences in elite effects suggest, with fewer among the UK schools, differences in allocations do exist, but these are the minority. There are 36 dyads of the same journal, year, and class of school. In 28 of these cases, the differences are not significant. In five cases, the UK schools allocate significantly more publications to entrepreneurship than the US schools, and in three cases the reverse is true.Footnote 5

5.5 Post hoc exploration

For purposes of the analyses above, business schools were aggregated into categories and publications were expressed relative to a school’s total works in the sample. We can also explore the individual elite schools, expressing entrepreneurship publications in absolute terms. We can also extend the time period to 5 years, 2015–2018, for the same reason that Journal Impact Factors are expressed for both 2 and 5 years: 2 years may have more anomalies than five. Results in absolute terms for each elite school are presented in Table 8. As with so much of scholarship, the results are highly skewed (Seglen, 1992). By this token, the US stringent elites skew to the bottom, largely ignoring the entrepreneurship journals. The main distinction is between that set of schools and all the others. We also see some schools, with MIT and Stanford standing out, that have well-known teaching programs but little interest in the entrepreneurship field journals. Stanford’s program demonstrates the elite predilection for analytical fields, as the academic head of its entrepreneurship program is an operations research professor.

6 Discussion and conclusions

6.1 Limitations

This study is based on archival data. These have the advantages of being widely available and non-obtrusive. However, the results are static. We cannot infer directionality of causation. This study also concerns only one aspect of business school stature—publications—although this measure does show a striking congruence between elite standing of both the university and the business school. Moreover, the relationship between approaches to management learning and the disciplinary focus of research is unknown. I have relied on an assumption, based only on my experience in research-oriented business schools, that research-active faculty wield the most influence on the curriculum and the prevailing conception of student learning. This assumption is, however, consistent with in the perceptions of McMullen (2019) and Wood (2020).

6.2 The USA is not the world

We see elite effects in both the UK and the US business schools, but we also see differences; in particular, the greater variation in UK publications. The impetus for elitism and the modes for its expression differ, as institutional norms are culturally and historically contingent (Vakkayil & Chatterjee, 2017; Veblen, 1918 [1899]: 133). For example, the greater age of the UK universities might afford their faculties more autonomy from external pressures, in the direction of either prestigious or managerial disciplines. Norms are also path-dependent. Compared with the staffing of US business schools by many economists, UK schools hired sociologists (Paul Tracey, personal communication). Furthermore, unlike the USA, the UK schools face a common set of scholarly standards, and the Research Assessment Exercise and Research Excellence Framework, along with the ABS and FT journal lists, appear to have leveled the playing field amongst disciplines (Pidd & Broadbent, 2015).

6.3 What should entrepreneurship scholars do going forward?

Should entrepreneurship scholars respond to these findings by trying to raise the prestige of their field still further, with US elites in particular, by imitating the analytical paradigms of economics and finance? According to Landström (2018; Landström & Harirchi, 2019), increases in the acceptance of entrepreneurship have followed just such a shift in method and in theory. Similar emulation has helped the acceptance of strategic management (Hambrick & Chen, 2008) and family business (Stewart, 2018). We have reason to think it could continue to work for entrepreneurship as well. US elites do not seem to deemphasize entrepreneurship scholarship as such; they deemphasize the non-analytical fields more generally. Moreover, the field does have a relatively analytical journal that helps the field’s legitimacy, Small Business Economics. (If finance can have the “Journal of Financial Economics,” can SBE be called the “Journal of Entrepreneurial Economics”?)

6.4 Implications for influencers: journal editors and deans

Editors of entrepreneurship journals affect the scholarly orientation of entrepreneurship professors. They could seek to increase the prestige of their journals with more mathematically sophisticated articles. They could incite this by judicious use of special issue topics and special issue editors. Alternatively, they could stay the course, and seek out works that serve the full range of enterprising students, and practitioners, in their myriad cultural, social, and affective contexts. The crux of our choices is who we wish to serve with our research. If we wish to serve only “enterprising individuals [seeking] lucrative opportunities in the form of economic rents, and downplaying social structure, context, and the remarkable heterogeneity of human desires” (Baker & Welter, 2017, p. 170; also Welter et al., 2017), we can get by only with economics-oriented scholarship and, for that matter, the dominance of teaching by non-research faculty. However, entrepreneurship is “an inherently heterogeneous phenomenon” (Audretsch et al., 2015, p. 709). Therefore, I hope we sustain a focus on scholarship that is deeply bound with relevance.

I hope we explore even more, not just exploit the prevailing templates of research (Shepherd, 2015). One hopeful trend is an increasing number of entrepreneurship journals with Web of Science standing. Younger journals with good 2019 JIF or SJR scores include the International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research (JIF 3.529; SJR 0.967), the International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal (JIF 3.472; SJR 1.164), and the Entrepreneurship Research Journal (JIF 1.643; SJR NA). Family Business Review (JIF 5.212; SJR 2.608) and the Journal of Family Business Strategy (JIF 3.927; SJR 1.763) also publish entrepreneurship research. Alternatives in outlets promote more innovation in publication. They help us resist perceived constraints on “theoretical eclecticism” (Aldrich, 2012, p. 1248) and help us explore uniquely entrepreneurial constructs (Wood, 2020).

Deans in elite US business schools might be pleased to note the findings in this study. However, shunning dedicated entrepreneurship research creates an important opportunity cost. Although the effort would not be easy, deans and other leaders could spur collaborative studies among practice-savvy instructors and entrepreneurship researchers. This could generate outputs with various media, which would be “useful for theory and practice” (Lawler et al., 1999). Such outputs would have positive “societal impact,” a key goal of the AACSB (AACSB, 2020). Perhaps the UK elites, and all schools that accommodate both scholarly and practice-based professors, are already leading the way in such an enterprise.

Notes

I remember this exchange clearly, but fallible memory is my source here. The panel would have been in the 1985 ICSB World Conference, held in Montreal, Canada. Thanks to Jerry Katz and George Solomon for filling in details for me.

Where possible, I used computer searches with journal ISSNs. In two cases, Journal of Management Information Systems and Review of Financial Studies, I counted articles manually.

We can assert that disjoint confidence intervals indicate difference, but the assertion that overlapping confidence intervals indicate insignificance (the heuristic used here) is not strictly true (Greenland et al., 2016).

For the US research schools, in the first period, ET&P receives significantly more than ISBJ and SBE and SEJ more than ISBJ. In the second period, ET&P and JBV receive more than ISBJ. For the UK quartile elites, in the first period, SBE receives significantly more than ET&P, and ISBJ and SBE receive more than SEJ. For the UK research schools, ISBJ receives more than both JBV and SEJ in the first period. In the second period, ISBJ and SBE both receive significantly more than any of the FT50 entrepreneurship journals.

The UK allocations are significantly higher for JBV among stringent elites in the second period, for ISBJ among the quartile elites in the first period and among the research schools in both periods, and for SBE among quartile elites in the first period. The US allocations are significantly higher for SEJ among research schools in the first period, for JSBM among research schools in the first period, and for SBE among research schools in the second period. There are no significant differences for ET&P.

References

AACSB. (2020). 2020 guiding principles and standards for business accreditation: Engagement, innovation, impact. Tampa, FL, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and Singapore: Author. https://www.aacsb.edu/-/media/aacsb/docs/accreditation/business/standards-and-tables/2020%20business%20accreditation%20standards.ashx?la=en&hash=E4B7D8348A6860B3AA9804567F02C68960281DA2

Abbott, A. (2001). Chaos of disciplines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Rosati, F. (2013). The importance of accounting for the number of co-authors and their order when assessing research performance at the individual level in the life sciences. Journal of Informetrics, 7(1), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2012.11.003.

Ahn, J., Oh, D.-h., & Lee, J. D. (2014). The scientific impact and partner selection in collaborative research at Korean universities. Scientometrics, 100(1), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-013-1201-7.

Aldrich, H. E. (2012). The emergence of entrepreneurship as an academic field: A personal essay on institutional entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 41(7), 1240–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.03.013.

Anderson, R. (2006). British universities: Past and present. London: Hambledon Continuum.

Anonymous. (1985). Guidelines for authors. Journal of Small Business Management non-indexed pages.

Audretsch, D. B., Kuratko, D. F., & Link, A. N. (2015). Making sense of the elusive paradigm of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 45(4), 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9663-z.

Baker, T., & Welter, F. (2017). Come on out of the ghetto, please! Building the future of entrepreneurship research. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 23(2), 170–184. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2016-0065.

Bernard, S. F. (1965). The economic and social adjustment of low-income, female-headed families. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Brandeis University.

Bollen, J., Rodriguez, M. A., & Van de Sompel, H. (2006). Journal status. Scientometrics, 69(3), 669–687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-006-0176-z.

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Freeman, L. C. (2002). UCINET 6 for Windows: Software for social network analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

Chan, K. C., & Liano, K. (2009). Threshold citation analysis of influential articles, journals, institutions and researchers in accounting. Accounting and Finance, 49(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-629X.2007.00254.x.

Chan, K. C., Chen, C. R., & Cheng, L. T. W. (2007). Global ranking of accounting programmes and the elite effect in accounting research. Accounting and Finance, 47(2), 187–220.

Dyllick, T. (2015). Responsible management education for a sustainable world: The challenges for business schools. Journal of Management Development, 34(1), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-02-2013-0022.

Foskett, N. (2011). Markets, government, funding and the marketisation of UK higher education. In M. Molesworth, R. Scullion, & E. Nixon (Eds.), The marketisation of higher education and the student as consumer, 25–38. London: Routledge.

Fowles, J., Frederickson, H. G., & Koppell, J. G. S. (2016). University rankings, evidence and a conceptual framework. Public Administration Review, 76(5), 790–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12610.

Franceschet, M. (2010). The difference between popularity and prestige in the sciences and in the social sciences: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 4(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2009.08.001.

Gardner, M. J., & Altman, D. J. (1986). Confidence intervals rather than P values: Estimation rather than hypothesis testing. British Medical Journal, 292(15), 746–750. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.292.6522.746.

González-Pereira, B., Guerrero-Bote, V. P., & Moya-Anegón, F. (2010). A new approach to the metric of journals’ scientific prestige: The SJR indicator. Journal of Informetrics, 4(3), 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2010.03.002.

Greenland, S., Senn, S. J., Rothman, K. J., Carlin, J. P., Poole, C., Goodman, S. N., & Altman, D. G. (2016). Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: A guide to misinterpretations. European Journal of Epidemiology, 31(4), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0149-3.

Hallfman, W., & Leydesdorff, L. (2010). Is inequality among universities increasing? Gini coefficients and the elusive rise of elite universities. Minerva, 48(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-010-9141-3.

Hambrick, D. C., & Chen, M.-J. (2008). New academic fields as admittance-seeking movements: The case of strategic management. Academy of Management Review, 33(1), 32–54. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.27745027.

Hanneman, R., & Riddle, M. (2005). Introduction to social network analysis. http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/nettext/Introduction_to_Social_Network_Methods.pdf

Harman, G., & Wood, F. (1990). Academics and their work under Dawkins: A study of five NSW universities. Australian Academic Researcher, 17(2), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03219473.

Hartmann, M. (2007). The sociology of elites. London: Routledge.

Hollis, A. (2001). Co-authorship and the output of academic economists. Labour Economics, 8(4), 503–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-5371(01)00041-0.

Jain, S. C., & Stopford, J. (2011). Revamping MBA programs for global competitiveness. Business Horizons, 54(4), 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.03.001.

Joy, S. (2006). What should I be doing and where are they doing it? Scholarly productivity of academic psychologists. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(4), 346–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/2Fj.1745-6916.2006.00020.x.

Katz, J. A. (2008). Fully mature but not fully legitimate: A different perspective on the state of entrepreneurship education. Journal of Small Business Management, 46(4), 550–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2008.00256.x.

Kerr, N. L. (1998). HARKing: Hypothesizing after the results are known. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2(3), 196–217. https://doi.org/10.1207/2Fs15327957pspr0203_4.

Kim, E. I., Morse, A., & Zingales, L. (2009). Are elite universities losing their competitive edge? Journal of Financial Economics, 93(3), 353–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.09.007.

Kuratko, D. F. (2005). The emergence of entrepreneurship education: Development, trends, and challenges. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 29(5), 577–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/2Fj.1540-6520.2005.00099.x.

Lambert, D. M., & Enz, M. G. (2015). We must find the courage to change. Journal of Business Logistics, 36(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12078.

Lampel, J. (2011). Torn between admiration and distrust: European strategy research and the American challenge. Organization Science, 22(6), 1655–1662. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0608.

Landström, H. (2010). Ian MacMillan. In Pioneers in entrepreneurship and small business research. International Studies in Entrepreneurship, 8, 295–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-23633-3_11.

Landström, H., & Harirchi, G. (2019). ‘That’s interesting!’ in entrepreneurship research. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(S2), 507–529. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12500.

Lawler III, E. E., Mohrman Jr., A. M., Mohrman, S. A., Ledford Jr., G. E., Cummings, T. G., & Associates. (1999). Doing research that is useful for theory and practice. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Leibenstein, H. (1950). Bandwagon, snob, and Veblen effects in the theory of consumers’ demand. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 64(2), 183–207. https://doi.org/10.2307/1882692.

Lepori, B., Geuna, A., & Mira, A. (2019). Scientific output scales with resources: A comparison of US and European universities. PLoS One, 14(10), e0223415. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223415.

March, J. G. (2018). Some thoughts on the development of disciplines, with particular attention to behavioral strategy. Advances in Strategic Management, 39, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0742-332220180000039001.

McMullen, J. S. (2019). A wakeup call for the field of entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(3), 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.02.004.

Medoff, M. H. (2006). Evidence of a Harvard and Chicago Matthew effect. Journal of Economic Methodology, 13(4), 485–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501780601049079.

Meyer, K. E., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Beugelsdijk, S. (2017). What’s in a p? Reassessing best practices for conducting and reporting hypothesis testing research. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(5), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-017-0078-8.

Oyer, P., & Schaefer, S. (2019). The returns to elite degrees: The case of American lawyers. ILR Review, 72(2), 446–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0019793918777870.

Pezzoni, M., Sterzi, V., & Lissoni, S. (2012). Career progress in centralized academic systems: Social capital and institutions in France and Italy. Research Policy, 41(4), 704–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.009.

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. T. (2002). The end of business schools? Less success than meets the eye. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 1(1), 78–95. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2002.7373679.

Pidd, M., & Broadbent, J. (2015). Business and management studies in the 2014 Research Excellence Framework. British Journal of Management, 26(4), 569–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12122.

Ronen, S., & Shenkar, O. (2013). Mapping world cultures: Cluster formation, sources and implications. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(9), 867–897. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.42.

Schäfer, T., & Schwarz, M. A. (2019). The meaningfulness of effect sizes in psychological research: Differences between sub-disciplines and the impact of potential biases. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, article 813. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00813.

Schwab, A. (2015). Why all researchers should report effect sizes and their confidence intervals: Paving the way for meta-analysis and evidence-based management practices. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 39(4), 719–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/2Fetap.12158.

Scott, W. R., & Biag, M. (2016). The changing ecology of U.S. higher education: An organization field perspective. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 46, 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0733-558X20160000046002.

Seglen, P. O. (1992). The skewness of science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 43(9), 628–638. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199210)43:9%3C628::AID-ASI5%3E3.0.CO;2-0.

Shepherd, D. A. (2015). Party on! A call for entrepreneurship research that is more interactive, activity-based, cognitively hot, compassionate, and pro-social. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(4), 489–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.02.001.

Siltaoja, M., Juusola, K., & Kivijärvi, M. (2019). ‘World-class’ fantasies: A neocolonial analysis of international branch campuses. Organization, 26(1), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1350508418775836.

Spender, J. C. (2014). The business school model: A flawed organizational design? Journal of Management Development, 33(5), 429–422. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-02-2014-0019.

Stewart, A. (2018). Can family business loosen the grips of accounting, economics, and finance? Journal of Family Business Strategy, 9(3), 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2018.06.001.

Stewart, A., & Miner, A. S. (2011). Prospects for family business in research universities. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 2(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2011.01.005.

Thomas, H., Thomas, L., & Wilson, A. (2013). The unfulfilled promise of management education (M.E.): The role, value and purposes of ME. Journal of Management Development, 32(5), 460–476. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711311328255.

Üsdiken, B. (2014). Centres and peripheries: Research styles and publication patterns in ‘top’ US journals and their European alternatives, 1960-2010. Journal of Management Studies, 51(5), 764–789. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12082.

Vakkayil, J., & Chatterjee, D. (2017). Globalization routes: The pursuit of conformity and distinctiveness by top business schools in India. Management Learning, 48(3), 328–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1350507616679347.

Veblen, T. (1918 [1899]). The theory of the leisure class: An economic study of institutions (New Edition). New York: The New Modern Library.

Weakliem, D. L., Gauchat, G., & Wright, B. R. E. (2012). Sociological stratification: Change and continuity in the distribution of departmental prestige, 1965-2007. The American Sociologist, 43(3), 310–327.

Wedlin, L. (2006). Ranking business schools: Forming fields, identities and boundaries in international management education. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Welter, F., Baker, T., Audretsch, D. B., & Gartner, W. B. (2017). Everyday entrepreneurship: A call for entrepreneurship research to embrace entrepreneurial diversity. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 41(3), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/2Fetap.12258.

Wood, M. S. (2020). Editorial: Advancing the field of entrepreneurship: The primacy of unequivocal “A” level entrepreneurship journals. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(5), 106019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stewart, A. Who shuns entrepreneurship journals? Why? And what should we do about it?. Small Bus Econ 58, 2043–2060 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00498-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00498-1