Abstract

Psychiatric conditions and sub-threshold psychiatric temperaments may influence entrepreneurs’ affect, cognition, energy, motivation, circadian rhythms, activity levels, self-concept, creativity, and interpersonal behaviors in ways that influence business outcomes. We used a self-report survey to examine the prevalence and co-occurrence of five psychiatric conditions among 242 entrepreneurs and 93 comparison participants. Mental health differences directly or indirectly affected 72% of the entrepreneurs in this sample, including those with a personal mental health history (49%) and family mental health history among the asymptomatic entrepreneurs (23%). Entrepreneurs reported experiencing more depression (30%), ADHD (29%), substance use (12%), and bipolar disorder (11%) than comparison participants. Furthermore, 32% of the entrepreneurs reported having two or more mental health conditions, while 18% reported having three or more mental health conditions. Asymptomatic entrepreneurs (having no mental health issues) with asymptomatic families constituted only 24% of the entrepreneur participants. Entrepreneurs’ psychiatric issues can affect their functioning and that of their ventures. Therefore, integrating knowledge about psychiatric conditions with research on personality traits can broaden the understanding of how mental health-related traits, states, and family history can influence entrepreneurial outcomes. We discuss methodological limitations as well as implications of our findings for entrepreneurship research and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction and theoretical context

Entrepreneurship research has examined personality traits associated with business outcomes. Related research has studied the general mental health and well-being (MWB) of entrepreneurs. By contrast, little is known about the nature, co-occurrence, and characteristics of psychiatric conditions and related sub-threshold temperaments that may be associated with these outcomes. Investigating psychiatric dimensions of entrepreneurship can enrich models of entrepreneurial personality and MWB in ways that matter for entrepreneurship research and practice. Using a self-report survey to examine the prevalence and co-occurrence of five psychiatric conditions among 242 entrepreneurs and 93 comparison participants, we found that mental health differences directly or indirectly affected 72% of the entrepreneurs in this sample, including those with a personal mental health history (49%) and family mental health history among the asymptomatic entrepreneurs (23%). Entrepreneurs reported experiencing more depression (30%), ADHD (29%), substance use (12%), and bipolar disorder (11%) than comparison participants. Furthermore, 32% of the entrepreneurs reported having two or more mental health conditions, while 18% reported having three or more mental health conditions. Asymptomatic entrepreneurs (having no mental health issues) with asymptomatic families constituted only 24% of the entrepreneur participants.

1.1 The personality characteristics of entrepreneurs

The personality of entrepreneurs has received significant attention (Baum and Locke 2004; Collins et al. 2004; Rauch and Frese 2007; Zhao et al. 2010), and meta-analyses of research findings have been conducted (Brandstätter 2011; Zhao et al. 2010; Zhao and Seibert 2006). The Big Five personality model, which specifies a set of overarching personality traits, composed of sub-traits or facets, is central to this research (Leutner et al. 2014; McCrae and Costa 2008). The Big Five traits (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) constitute enduring core propensities that are assumed to have a biological basis, and remain relatively stable over time (Digman 1990; McCrae and Costa 2008).

Entrepreneurs manifest a clear pattern of Big Five personality traits (Brandstätter 2011; Obschonka et al. 2013; Zhao et al. 2010), which consists of higher levels of extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness coupled with lower levels of agreeableness and neuroticism (Zhao et al. 2010; Zhao and Seibert 2006). The C+ O+ E+ N− A− footprint differentiates entrepreneurs from managers, the C+ O+ N− E+ footprint predicts entrepreneurial intention, and the C+ O+ E+ N− footprint predicts entrepreneurial performance (Brandstätter 2011).

Entrepreneur personality traits that do not map to the Big Five model include self-efficacy, risk propensity, internal locus of control, proactive personality, stress tolerance, need for autonomy, achievement motivation, innovativeness, and passion (Baum and Locke 2004; Brandstätter 2011; Cardon et al. 2009; Collins et al. 2004; Fuller and Marler 2009; Rauch and Frese 2007; Seibert et al. 1999; Stewart and Roth 2001). A blend of traits (self-efficacy), skills (goal setting), and motivated extraversion (communicated vision) directly affects venture growth as modulated by passion, tenacity, and new resource skill (Baum and Locke 2004). Traits that match to business tasks—including need for achievement, generalized self-efficacy, innovativeness, stress tolerance, need for autonomy, and proactive personality—associate with success (Rauch and Frese 2007).

A dynamic or “gravity” model places component personality traits within a hierarchical Entrepreneurial Personality System (EPS) in which the broad Big Five traits are viewed as pervasive and genetically determined basic tendencies (Obschonka and Stuetzer 2017). By contrast, specific traits like risk propensity, self-efficacy, and internal locus of control are regarded as learnable and more malleable. Within the EPS model, the Big Five traits are construed to exert a shaping or gravitational influence on the more distal personality characteristics which are seen as context-sensitive adaptations that guide entrepreneurial decision-making and behavior.

Personality literature leaves open questions related to the role of affect, and by extension the role of affective disorders, in entrepreneurial outcomes. Affective states linked to psychiatric conditions may modulate the influence of personality traits on entrepreneurial results. For example, entrepreneurs will be less extraverted (personality trait) when they are depressed (psychiatric condition), and entrepreneurs will take more risks (personality trait) when they are manic or inebriated (psychiatric conditions). Thus, psychiatric conditions (e.g., mania) are associated with personality traits (e.g., optimism) and affective states (positivity) that can shape entrepreneurial outcomes within the context of differing personalities under varying internal (e.g., hormonal) or external (e.g., length of day, access to capital) circumstances which may suppress or trigger (inhibit or disinhibit) symptom onset and symptom intensity fluctuations.

1.2 Entrepreneur mental health and well-being

A related literature has examined the mental health and well-being (MWB) of entrepreneurs in comparison to that of employees. MWB research derives from the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of mental health which includes both the absence of mental illness and the presence of well-being, living up to one’s potential, positive coping and adaptation, productivity, and community engagement (World Health Organization 2014).

Entrepreneur MWB studies generally find that entrepreneurship cushions the health impact of high stress (Hausser et al. 2010) and that the well-being among entrepreneurs with broad-ranging mental health issues is not lower than the overall well-being among entrepreneurs without mental health problems (Jang et al. 2015; Kawakami et al. 1996; Stephan and Roesler 2010; Torske et al. 2016). The autonomy, independence, and ownership central to entrepreneurship may cushion the self-employed against realizing the full negative impact of high stress, uncertainty, and pressure (Lewin-Epstein and Yuchtman-Yaar 1991). Stressors may be appraised as less threatening by entrepreneurs and may cause less subjective distress (Hausser et al. 2010).

Many large studies confirm these findings. One nationally representative study found that 149 German self-employed individuals did not differ from their age- and gender-matched, employed comparison participants in prevalence rates of affective disorders, anxiety disorders, or alcohol abuse (Stephan and Roesler 2010). Entrepreneurs had a lower incidence of lifetime mental health diagnoses and higher life satisfaction than the employed participants. Similarly, a study of 238 entrepreneurs and 288 managers in the USA showed no differences on measures of depression, anxiety, and anger (Rahim 1996). A study of more than 2700 US citizens found that entrepreneurs experience lower rates of emotional negativity and exercise constructive emotion and problem focused coping methods more freely and frequently than employees (Patzelt and Shepherd 2011). A study of 235 Canadian entrepreneurs and matched employed controls found no significant mental health or job satisfaction differences between these groups (Jamal 1991; Jamal and Mitchell 1980).

Elevated MWB among entrepreneurs has been linked with persistence, or tenacity and grit (Wincent et al. 2008) which can mitigate the toxic effects of stress (Patzelt and Shepherd 2011). For example, a study of 688 self-employed Americans and a matched sample of 688 employees explored the health and wellness trade-offs tied to entrepreneurship in (Cardon and Patel 2015). Entrepreneurs in this study experienced higher stress, which was associated with higher rates of positive affect and increased income. Positive affect that strengthens persistence was found to mitigate the negative impact of stress on the physical health of the entrepreneurs. A positive relationship between MWB and firm performance has been noted (Gorgievski et al. 2010; Gorgievski and Stephan 2016).

By contrast, studies conducted by Parslow et al. (2004), Binder and Coad (2013), and Saarni et al. (2008), women, entrepreneurs with employees, farmers, and necessity versus opportunity entrepreneurs demonstrated elevated mental and/or physical health challenges compared to other self-employed people. Entrepreneur MWB research has not evaluated how diagnosable psychiatric conditions might make entrepreneurs more at risk or more resilient.

1.3 Psychiatric dimensions of entrepreneurship

Abundant research on entrepreneur personality and MWB contrasts with a relative dearth of research on the psychiatric dimensions of entrepreneurship. Some popular books suggest the importance of this issue. Authors have described bipolar spectrum conditions (Gartner 2008; Ghaemi 2011), obsessive-compulsive disorders, and other severe conditions among business tycoons (Barlett and Steele 2004; Ludwig 1992) and political and military leaders (Ghaemi 2011; Hershman and Lieb 1994; Hershman and McFarlane 2002; Jamison 1995).

1.4 How psychiatric disorders interact with personality traits

Psychiatric disorders are genetically transmitted and environmentally modulated conditions that affect brain functioning (Burmeister 2015; Doherty and Owen 2014; Gratten et al. 2014; Sullivan et al. 2012, 2017) characterized by symptom clusters that may present with varying levels of severity (Goekoop and Goekoop 2014; Walter 2013). Specific temperaments are associated with specific psychiatric conditions (Clauss et al. 2015; Trofimova and Sulis 2016). Temperaments are dispositional and enduring biological response styles (Caspi and Silva 1995; Dyson et al. 2015).

Psychiatric conditions produce fluctuating states of mind that correspond to fluctuations in severity of illness. These fluctuations may warp the expression of underlying personality traits. For example, symptoms associated with anxiety disorders include worry, catastrophic thinking, and risk aversion (American Psychiatric Association 2013). When anxiety is elevated, an open-minded (personality trait) entrepreneur may be less likely to try something new due to elevated risk aversion (symptom). An extraverted (personality trait) entrepreneur may be less likely to engage with investors, customers, and employees while isolating (symptom) during a depression. The shifting cognitive-affective-behavioral state changes that result from the expression of psychiatric conditions may thus shape the expression of the entrepreneur’s personality and its impact on behaviors that produce business results.

Psychiatric symptoms (e.g., elevated creativity) that cluster with specific psychiatric conditions (e.g., bipolar disorder, depression, substance use conditions, and ADHD) (Andreasen 1987, 2008, Healey and Rucklidge 2006, 2008; Ludwig 1992; Post 1994, 1996) may be particularly relevant to entrepreneurship. As the wealth of nations has come to depend upon citizens with a wealth of notions, an elite “creative class” has emerged (Florida 2002). The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the study hypotheses and supporting literature. Section 3 explains methods. Section 4 focuses on findings, while Section 5 discusses the limitations of this study. Finally, Section 6 discusses implications for entrepreneurship theory, research, and practice.

2 Hypotheses and supporting literature

This study focused on three dimensions of psychiatric research that the existing literature suggests may be relevant to entrepreneurship. First, we examine the prevalence of a thoughtfully selected and limited set of psychiatric disorders among a sample of entrepreneurs. These conditions include depression, ADHD, anxiety, substance use disorders, and bipolar spectrum conditions. The author has provided over 5000 hours of direct psychiatric care to entrepreneurs, and these are the five conditions that have occurred most commonly among entrepreneurs in this psychiatric practice. Second, we explore the co-occurrence of psychiatric conditions, or the extent to which an entrepreneur who reports having one condition may also report having a second condition. Finally, we assess the extent to which entrepreneurs report mental health conditions among their first-degree family members. Since entrepreneurs may inherit beneficial traits (e.g., creativity and motivation) related to a psychiatric condition (e.g., bipolar disorder), without expressing the condition itself, we evaluated the extent to which asymptomatic entrepreneurs (reporting no mental health issues) report having family members with psychiatric conditions. The three dimensions of our research are put into three hypotheses below which are backed up with supporting literature.

2.1 Hypothesis 1 (H1): the prevalence of ADHD, substance use disorders, and mood disorders among entrepreneurs is likely to be greater than that among a normal comparison sample.

Existing literature identifies several psychiatric conditions that have associated traits, features, symptoms, and subthreshold temperaments that directly relate to entrepreneurship. These factors impact the affect, cognition, energy, activity, rhythmicity, and behaviors that are critical for entrepreneurship. Some examples are identified below.

2.1.1 Creativity and innovativeness

Entrepreneurs must generate creative novel ideas for innovative new businesses (Dyer et al. 2008). The proclivity to innovate is a main driver of the intention to become an entrepreneur, business creation, and business success (Hmieleski and Corbett 2006; Rauch and Frese 2007). Innovation makes companies more adaptive to change and enhances business performance (Drucker 1998; Neely and Hii 1998).

Researchers have identified a relationship between creativity and psychiatric conditions including psychosis (Kyaga et al. 2011, 2013; Ludwig 1992), bipolar disorder (Andreasen 2008; Jamison 1995; Kyaga et al. 2011; Richards et al. 1988; Santosa et al. 2007; Simeonova et al. 2005), depression (Andreasen 2008; Ludwig 1992), ADHD (Healey and Rucklidge 2006), and substance abuse (Kyaga et al. 2013; Ludwig 1992; Post 1994, 1996). Fluctuations in creativity and creative output correspond to fluctuations in mood (Jamison 1995).

2.1.2 Goal attainment, achievement motivation, and mania; goal disengagement, apathy, and depression

Goal attainment has a direct effect on venture growth (Baum and Locke 2004). Achievement motivation is significantly correlated with the choice to become an entrepreneur, with business creation, and with business success (Brandstätter 2011; Collins et al. 2004; Rauch and Frese 2007).

Several studies have indicated a correlation between bipolar spectrum conditions and high achievement (Coryell et al. 1989; MacCabe et al. 2010; Verdoux and Bourgeois 1995). Bipolar conditions and hypomanic personality have been linked to having ambitious goals, expecting to succeed, goal engagement, zealous pursuit, striving, and goal attainment (Gruber and Johnson 2009; Johnson 2004; Johnson et al. 2009). Entrepreneurs must also cope with failure and relinquish ambitious goals which cannot be attained. Clinging to unattainable goals is linked to the onset of depression, and depression causes loss of motivation (apathy) and has been shown to facilitate disengagement from unattainable goals (Koppe and Rothermund 2017).

2.1.3 Risk propensity

Risk propensity is correlated with business foundation (Brandstätter 2011). A meta-analysis of personality differences between entrepreneurs and managers reported in 12 large studies found that the risk propensity of entrepreneurs is greater than that of managers and that the largest differences are found among the entrepreneurs whose primary goal is business growth, rather than family income (Stewart and Roth 2001). Similarly, a personality study of 500 top-level executives found that the most successful executives were the biggest risk takers (MacCrimmon and Wehrung 1990).

Risk propensity and impulsivity are associated with ADHD (Bakhshani 2013; Drechsler et al. 2008; Shoham et al. 2016), bipolar spectrum conditions (Alloy et al. 2012; Reddy et al. 2014; Strakowski et al. 2010; Swann et al. 2001), substance use disorders (Birkley and Smith 2011; Feldstein and Miller 2006; Kreek et al. 2005; Lejuez et al. 2010), and the co-occurrence of these conditions (Holmes et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2011; Moeller et al. 2001; Upton et al. 2011; Zuckerman and Kuhlman 2000).

2.1.4 Bipolar disorder

Akiskal et al. (2005) studied 263 professionals affiliated with an outpatient psychiatric practice. They found that of the seven job classifications studied (physicians, lawyers, managers, industrialists, architects, journalists, and artists), self-made industrialists (entrepreneurs) had the highest rates of hyperthymic traits of all the groups studied, which was three times the rate found in a matched comparison group composed of psychiatric outpatients who did not work in these seven professions (Akiskal et al. 2005). Hyperthymic traits include the tendency to experience positive moods and emotions, and dispositional positive affect, which have been linked to a variety of both positive and negative outcomes among entrepreneurs (Baron et al. 2011, 2012). One of the current authors recognized the concordance between personality traits associated with successful entrepreneurs and those associated with bipolarity (Freeman 2013).

A longitudinal Danish registry study of over 3.4 million individuals between the ages of 20–60 born in cohorts from 1946 to 1975 determined that individuals at higher risk of bipolar disorder are more likely to be self-employed, more likely to be incorporated, and more likely to be in the top 10% of income earners (Biasi et al. 2015). This study also found that access to lithium, a medication used to treat bipolar disorder, reduces the income penalty experienced by workers with bipolar-related disabilities and further increases the likelihood that bipolar entrepreneurs will be among the top income earners. The authors suggest that bipolar traits such as elevated levels of optimism, confidence, creativity, impulsivity, and risk tolerance may contribute to these results.

Dispositional positive affect (DPA), a trait associated with hypomania, is related to positive outcomes such as career success, enriched social networks, and superior task performance (Baron et al. 2011, 2012). DPA among entrepreneurs was significantly related to product innovation and sales growth rate, two measures of firm performance in a study of 157 entrepreneurs. Findings also identified a “downside of being up” in that excessive DPA was associated with declines in firm performance.

Entrepreneurs may benefit from increased activity and energy which is found among people with bipolar disorder (Machado-Vieira et al. 2017). However, investigation of the relationship between bipolarity and entrepreneurship failed to demonstrate a main effect, indicating that such a relationship, if any, is more nuanced, moderated, and indirect (Johnson et al. 2015a). Further exploration of the overlap between entrepreneurs and those with bipolar disorder found that the following four traits common to mania risk also appeared significantly related to entrepreneurial intent: hubristic pride,Footnote 1 improvisational proclivity,Footnote 2 proactive personality, and extraversion (Johnson et al. 2018).

2.1.5 ADHD

Several authors have cited a relationship between entrepreneurship and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In a 16-year prospective study of 91 children with ADHD and 95 comparison participants, Mannuzza and colleagues determined that 19% of probands (participants with ADHD), versus 5% of controls, owned and operated their own business as adults (Mannuzza et al. 1993). A study of 306 French entrepreneurs found that those with ADHD symptoms had elevated entrepreneurial orientation (Thurik et al. 2016), a predictor of small firm survival and growth (Rauch et al. 2009). A study of 10,000 Dutch university students found that those with ADHD-like behavior had higher entrepreneurial career intentions compared to the others (Verheul et al. 2015, 2016).

Structured diagnostic interviews of 14 Swedish entrepreneurs with ADHD identified traits such as impulsivity, intuitive decision-making, and novelty seeking that facilitate entrepreneurial behavior (Wiklund et al. 2016b). Significantly higher values in entrepreneurial tendency measures and a significantly higher marginal probability of being entrepreneurs were found among 103 ADHD participants in a survey that included 167 comparison participants (Dimic and Orlov 2014). Dopamine receptor genes have been associated with sensation seeking, novelty seeking, entrepreneurship, and ADHD (Nicolaou et al. 2011). Taken together, this body of research suggests a positive fit between entrepreneurship capacities and ADHD-like symptoms of heightened creativity, risk taking, innovation, proactive behavior, and novelty and sensation seeking. Entrepreneurship may offer a unique opportunity for people with ADHD-like behaviors to excel.

Studies also suggest that other ADHD-like qualities may adversely impact entrepreneurial outcomes. These include lower rates of conscientiousness, higher rates of urgency, impatience, difficulties completing uninteresting or repetitive tasks, inattentiveness, over-relying on intuitive decision-making, and preferring quick action over thoughtful analysis, which sometimes leads to acting without thinking (Organ et al. 2016; Wiklund et al. 2016a). As a result, entrepreneurs with ADHD had mixed results in bookkeeping, accounting, and some critical business decisions, and yet entrepreneurship still provides more opportunities for them to excel then being an employee (Wiklund et al. 2016b).

2.1.6 Addiction

“Entrepreneurship addiction,” the compulsion to create and grow new ventures (serial entrepreneurship) has been compared to other behavioral addictions such as gambling. Aspects of entrepreneurship may activate neural reward circuits and disinhibit and reinforce the compulsive and addictive behaviors of entrepreneurs who may be predisposed and vulnerable to addiction (Murdoch et al. 2007; Spivack et al. 2014). Substance use disorders (SUDs) have been noted among entrepreneurs in a number of different occupations and may be a way in which entrepreneurs cope with stress (Leignel et al. 2014; Lin et al. 2003).

Substance use disorders are also known to be associated with features of entrepreneurship, such as chronic stress, impulsivity, ADHD, depression, and mood conditions (Brady and Sinha 2005; Dawe et al. 2004). One study found no significant relationship between substance use disorders involving “soft” recreational drugs (such as cannabis, ecstasy, LSD, and mushrooms) and occupational attainment, but “harder,” more addictive drugs (such as heroin and cocaine) have been found to correlate with unemployment (MacDonald and Pudney 2000). The use of “soft drugs” may not harm the performance of entrepreneurs and may facilitate coping. For example, elevated levels of psychological distress were associated with increased alcohol and cigarette use in one study of 2435 self-employed professionals (Leignel et al. 2014).

2.2 Hypothesis 2 (H2): entrepreneurs will report a greater number of co-occurring mental health conditions than will participants in a comparison sample

This paper proposes that many traits associated with entrepreneurial success are also features of diagnosable psychiatric disorders. For example, risk propensity is associated with ADHD, bipolar spectrum conditions, and SUDs. Consequently, we suggest that entrepreneurs who are highly endowed with a plethora of successful personality traits may also be expected to have a greater number of diagnosable psychiatric conditions. Most entrepreneurs seen in the principal investigator’s psychiatric practice present with two or more co-occurring conditions. However, the authors could not identify any prior research addressing the co-occurrence of additional mental health conditions among entrepreneurs with an index diagnosis.

The co-occurrence of two or more mental health conditions affecting individuals with psychiatric diagnoses is common and has been studied in several large samples. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication interviewed a representative sample of 9282 English-speaking American adults to determine the lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental health conditions. This study found a 46% lifetime occurrence of any mental health condition, an 18.3% lifetime occurrence of one mental health condition, a 27.7% lifetime occurrence of two or more conditions, and a 17.3% lifetime occurrence of three or more conditions (Kessler et al. 2005). This same study found a 26.2% 12-month occurrence of any mental health condition, a 14.4% 12-month occurrence of one mental health condition, a 5.8% 12-month occurrence of two mental health conditions, and a 6% 12-month occurrence of three or more mental health conditions (Kessler et al. 2005). A large body of research indicates that the five conditions investigated in this study are highly comorbid with each other as well as with additional diagnoses (Alegría et al. 2010; Bernardi et al. 2012; Biederman et al. 1995; Brawman-Mintzer et al. 1993; de Graaf et al. 2002; Faraone et al. 2012; Kessler et al. 2006; McElroy et al. 2001; McGough et al. 2005; Sachs et al. 2000; Simon et al. 2004).

Co-occurring mental health conditions may empower entrepreneurs by moderating the way in which an index condition is expressed. For example, anxiety plus ADHD is one pattern of condition co-occurrence. Fear (anxiety) such as fear of failure can mitigate the impulsivity, disinhibition, and lower conscientiousness that is common among those with ADHD. Investigators propose that entrepreneurs may use their anxiety to self-regulate and compensate for impulsive behaviors otherwise inherent to their ADHD (Organ et al. 2016).Twenty-five percent of people with ADHD also have co-occurring anxiety conditions (Schatz and Rostain 2006), which may partially inhibit the impulsivity associated with ADHD.

2.3 Hypothesis 3(H3): the first-degree relatives of asymptomatic entrepreneurs are likely to have more mental health conditions than the first-degree relatives of asymptomatic comparison participants

Many entrepreneurs may have no mental health conditions. Could these asymptomatic entrepreneurs be the high-functioning, well-adjusted, and resilient ambassadors of families with a higher-than-expected prevalence of mental health conditions? If so, the families of asymptomatic entrepreneurs may be burdened by mental health challenges while the asymptomatic entrepreneurs may be blessed with just enough of the disease-related creativity, energy, optimism, and other advantageous qualities that empower them to succeed, without being burdened by more extreme mental health symptoms that result in disability.

Little is known about mental health conditions among the families of entrepreneurs. However, previous research has shown that first- and second-degree family members of bipolar probands are high achievers across several domains that are important for entrepreneurship (Higier et al. 2014). For example, as compared to bipolar probands and normal controls, the unaffected identical twins of people with bipolar disorder demonstrate superior cognitive and interpersonal traits that seem important for entrepreneurship, including enhanced social ease, confidence, assertiveness, intelligence, verbal learning, verbal fluency, extraversion, sociability, optimism, and resilience.

Coryell et al. (1989) found that the first-degree relatives of bipolar probands, including relatives with bipolar spectrum conditions, had significantly higher educational and occupational achievement than the close family members of people with other mental health conditions. Other studies conducted over the last 100 years have reached similar conclusions (Bagley 1973; Johnson 2004; MacCabe et al. 2010; Monnelly et al. 1974; Verdoux and Bourgeois 1995; Woodruff et al. 1968).

Creativity and innovativeness are foundational aptitudes of entrepreneurs. The close family members of bipolar probands have been shown to have high levels of creativity (Andreasen 1987; Richards et al. 1988). People with bipolar spectrum conditions were found to be over-represented in the scientific and artistic occupations, and conditions identified among their first-degree relatives include schizophrenia, anorexia nervosa, and autism (Kyaga et al. 2013). Male relatives of people with schizophrenia were shown to be overrepresented in a listing of prominent people (Karlsson 1970).

Drawing on the findings of heightened accomplishment and creativity in families of those with mental health conditions, particularly bipolar disorder, we assessed the possibility that unaffected entrepreneurs may come from families with a significant prevalence of mental health conditions.

3 Methods

The researchers used self-report survey instruments to gather data about the reported prevalence, co-occurrence, and familiality of five psychiatric conditions among a sample of entrepreneurs and a comparison group. Data was analyzed from 76 MBA student and faculty pool participants, 149 psychology students, and 110 entrepreneurs not affiliated with the university. Participants from either recruitment group who reported a history of self-employment or founding or co-founding a for-profit or non-profit business were categorized as entrepreneurs (n = 242). Participants who did not endorse this question served as the comparison participants in the comparison (“control”) category (n = 93). Research procedures were approved by the University of California Berkeley Institutional Review Board before data was collected.

3.1 Participants

All participants completed informed consent procedures online and verified that they were at least 18 years of age. The study was advertised as a study of entrepreneurship and personality. All measures were completed online. Participants completed multiple measures, including items not described here.

Participants were from two primary recruitment groups. The first recruitment group (N = 239) was composed of undergraduate psychology students (N = 157) as well as MBA graduate students and faculty members (N = 82). This group was recruited through the research participation pools of a large public university website listing multiple studies. Undergraduate psychology students received course credit for participation. MBA graduate students and faculty members were paid $15 for study participation. Total survey duration for this group was 1 h and included multiple measures not reported here.

The second recruitment group (N = 210) consisted of entrepreneurs who were recruited through study advertisements posted on entrepreneurship websites and newsletters, at entrepreneurship conferences, meet-up groups, and organizations, by viral outreach marketing, and by circulation to associates of the principal investigator. The total duration of the measure taken by entrepreneurs was 10–15 min.

After excluding participants for failing catch items (e.g., “please select two as your answer”) and incomplete responses, data was analyzed from 76 MBA student and faculty pool participants, 149 psychology students, and 110 entrepreneurs. Participants from either recruitment group who endorsed, “Have you ever been self-employed, a business founder, or a business co-founder (including non-profit businesses) (Zhang et al. 2009)” were categorized as entrepreneurs (n = 242). Participants who did not endorse this question served as the comparison participants in the comparison (“control”) category (n = 93).

The combined sample was predominantly male (70.5%). Average age was distributed: 22.7% between the ages of 18–30 years old, 25% between the ages of 31–39 years old, and 24.5% between the ages of 41–49 years old. Participants identified as 72.9% Caucasian, 12.8% other, 10% Asian, 3.8% Middle Eastern, and 0.5% African American. This dataset has been referenced in three prior publications (Johnson et al. 2015a, b; Johnson et al. 2015).

3.2 Measures

To report personal and family mental health history, participants completed a self-report measure of psychiatric history for self and first- (parents, siblings, or children) and second- (aunts, uncles, grandparents) degree family members. Participants indicated whether they had experienced personal or family diagnoses of ADHD, substance use conditions, bipolar disorder, depression, or anxiety. In addition, items covered a history of suicide attempt and psychiatric hospitalization among the participants and their family members and completed suicides among family members. The self-report instrument was based upon the Family History of Risk for Mania (FIRM) (Algorta et al. 2013), a self-report instrument which surveys a more limited set of conditions.

3.3 Analysis plan

To determine whether entrepreneurs and the non-entrepreneurial comparison group differed in either their personal psychiatric or family psychiatric histories, we conducted a series of chi-square tests and t tests, with alpha = 0.05. Two-tailed tests were used.

4 Findings

In the present section, we will confront the three hypotheses with our data using five figures. Figures 1 and 2 present data in support of H1 (the prevalence of ADHD, substance use disorders, and mood disorders among entrepreneurs is likely to be greater than that among a normal comparison sample); Figure 3 presents data in support of H2 (entrepreneurs will report a greater number of co-occurring conditions than will participants in a comparison sample), while Figs. 4 and 5 present data in support of H3 (the first-degree relatives of asymptomatic entrepreneurs are likely to have more mental health conditions than the first-degree relatives of asymptomatic comparison participants).

4.1 How many entrepreneurs and controls report having mental health conditions (ADHD, alcohol/drugs, bipolar, depression, anxiety)?

As shown in Fig. 1, more of the entrepreneurs in this study, 119 (49% of the 242) reported having a mental health condition than did the non-entrepreneurs, of whom 30 (32% of the 93) reported having a mental health condition (Χ2 = 8.67, n = 327, p < 0.01). Figure 1 shows support for H1 (the prevalence of ADHD, substance use disorders, and mood disorders among entrepreneurs is likely to be greater than that among a normal comparison sample.)

4.2 Which mental health conditions do entrepreneurs and controls endorse having?

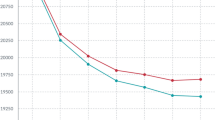

Entrepreneurs in the study reported higher rates of ADHD (Χ2 = 21.71, n = 310, p = < 0.01), substance use (Χ2 = 4.48, n = 319, p = 0.03), depression (Χ2 = 8.46, n = 311, p < 0.01), and bipolar disorder (Χ2 = 9.09, N = 311, p < 0.01) than comparison participants. As illustrated in Fig. 2, entrepreneurs did not report higher rates of anxiety than did participants in the comparison sample (Χ2 = 0.62, n = 305, p = 0.43). Figure 2 also shows support for H1 (the prevalence of ADHD, substance use disorders, and mood disorders among entrepreneurs is likely to be greater than that among a normal comparison sample). Mood disorders include both depression and bipolar disorder. Note that anxiety levels are comparable between the two groups.

4.3 How many co-occurring mental health conditions do entrepreneurs versus controls report having?

Figure 3 illustrates that the entrepreneurs in this sample reported more co-occurring mental health conditions than did the comparison participants (t(175) = 4.01, N = 328, p < 0.01). In this sample, 32% of entrepreneurs reported two or more co-occurring mental health conditions, and 18% reported three or more co-occurring conditions. Figure 3 shows support for H2 (entrepreneurs will report a greater number of co-occurring mental health conditions than will participants in a comparison sample).

4.4 How many asymptomatic entrepreneurs versus controls report mental health conditions among their first-degree relatives?

Figure 4 illustrates that the asymptomatic entrepreneurs in this sample, those who report no prior psychiatric history, were twice as likely to report one or more mental health conditions among their first-degree relatives than were the asymptomatic comparison participants, a difference that was statistically significant (Χ2 = 10.68, n = 175, p < 0.01). Figure 4 shows support for H3 (the first-degree relatives of asymptomatic entrepreneurs are likely to have more mental health conditions than the first-degree relatives of asymptomatic comparison participants).

4.5 What is the prevalence of mental health conditions among entrepreneurs and their immediate families (first-degree relatives)?

Figure 5 shows that asymptomatic entrepreneurs with symptomatic families (diagnosable mental health conditions reported among parents, siblings, and/or children) constitute 23% of the entire sample of 242 entrepreneurs, while asymptomatic entrepreneurs with asymptomatic families constitute 24% of the entire study sample of 242 entrepreneurs. Figure 5 shows support for both H1 (the prevalence of ADHD, substance use disorders, and mood disorders among entrepreneurs is likely to be greater than that among a normal comparison sample) and H3 (the first-degree relatives of asymptomatic entrepreneurs are likely to have more mental health conditions than the first-degree relatives of asymptomatic comparison participants).

Reviewed in conjunction with the results displayed in Fig. 1 and shown again here, 72% of the entrepreneurs in this sample either reported a personal mental health history (49%) or were asymptomatic yet reported a family mental health history (23%). By contrast, 48% of the comparison participants in this sample either report a personal mental health history (32%) or were asymptomatic yet reported a family mental health history (16%).

Taken together, we find support for the three hypotheses. Entrepreneurs report a higher lifetime mental health burden (H1) because they have higher levels of specific conditions and more co-occurring conditions (H1 and H2) and because more of their family members have mental health problems (H3). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the absolute difference in lifetime mental health burden between the entrepreneurs and comparison participants in this sample (49 vs. 32%), as well as the prevalence of specific conditions among both groups (elevated mood disorders, ADHD, and substance use conditions among the entrepreneurs). Figure 3 shows support for H2 (entrepreneurs will report a greater number of co-occurring mental health conditions than will participants in a comparison sample). Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the absolute difference in mental health burden between the family members of asymptomatic entrepreneurs and asymptomatic comparison participants in this sample (48 vs. 24%) and the greater impact of mental health conditions on entrepreneurs and their families compared with the impact of mental health conditions on comparison participants and their families (72 affected vs. 48% affected).

5 Limitations

These results are limited by reliance on self-report measures, vulnerability to shared method variance, possible selection bias, comparison group characteristics, and study design considerations. Therefore, the current findings must be considered preliminary.

5.1 Self-report measures

This study relied upon self-reported measures of personal and family mental health history, which may be subjective, and limited by awareness of family concerns, understanding of psychiatric terms, and unwillingness to describe potentially stigmatizing information (Furnham 1986; van de Mortel 2008).

Self-report mental health surveys may underestimate the lifetime prevalence of mental health conditions (Takayanagi et al. 2014), including ADHD (Kooij et al. 2008), bipolar spectrum conditions (Merikangas et al. 2007), depression (Hunt et al. 2003), and alcoholism (O’Farrell and Maisto 1987). A related concern is that the instrument used to assess mental health in this study has not been validated with this population. Future research on this subject should include a broader array of validated, condition-specific psychometric instruments and interview-based diagnostic assessments.

5.2 Shared method variance

People who tend to answer yes to most questions could skew findings to suggest a larger correlation between entrepreneurship and mental health concerns (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

5.3 Selection bias

The entrepreneur participants in this convenience sample may have been attracted by or interested in the mental health issues being examined. Future research could control for the possibility of selection bias by using a registry-based approach to data collection in which priming, recruitment channels, and non-response are not methodological issues.

5.4 Validity of the comparison group

This study relied upon a convenience comparison sample. On average, comparison participants were younger than the entrepreneurs. Since more entrepreneurs may have reached or passed the median age of onset for substance use conditions (age 19–23 years) and mood conditions (age 25–32 years), lifetime mental health conditions among the comparison sample may be underreported (Kessler et al. 2005). The comparison participants were drawn from a prestigious school and may have had fewer mental health issues by virtue of this signal of academic success. Future research should include a demographically matched comparison group of employees from the same economic sectors as the entrepreneurs.

6 Interpretation and conclusion

This study builds upon previous findings about entrepreneurs’ personality and mental health and well-being (MWB) by examining the prevalence and co-occurrence of five psychiatric conditions commonly found among entrepreneurs and the family psychiatric history of entrepreneurs with and without psychiatric conditions. Psychiatric conditions and their related states and traits appear important for understanding entrepreneurial affect, cognition, motivation, behavior, outcomes, and well-being. Current findings add to a growing body of work suggesting that mental health symptoms and conditions, in individuals and their family members, may co-occur with highly advantageous outcomes that benefit both the individual and society. Understanding the strengths and vulnerabilities associated with personal and familial mental health histories may contribute to improved entrepreneurial outcomes and to the development of protective resources for entrepreneurs. Here, we address an interpretation of the findings, plus some implications for entrepreneurship theory, research, and practice.

6.1 Prevalence and co-occurrence of mental health conditions among entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurs in this sample were more likely to report having a lifetime history of any mental health condition (49%), depression (30%), ADHD (29%), substance use conditions (12%), and bipolarity (11%) than were comparison participants.

Symptomatic entrepreneurs in this study also reported a greater number of co-occurring mental health conditions than were reported by symptomatic comparison participants. While 49% of entrepreneurs in this sample report having any mental health condition, 32% of the entrepreneurs report having two or more mental health conditions and 18% report having three or more mental health conditions.

6.2 Family history of mental health conditions

Twenty-three percent of the entrepreneurs in this sample who reported no prior psychiatric history also described more psychiatric conditions among their first-degree family members than were found among the first-degree relatives of asymptomatic comparison participants.

Mental health differences thus directly or indirectly affected 72% of the entrepreneurs in this sample, including those with a personal mental health history (49%) and family mental health history among the asymptomatic entrepreneurs (23%). Asymptomatic entrepreneurs with asymptomatic families constituted only 24% of the entrepreneur participants. (Data on this issue was missing for 4% of the entrepreneurs surveyed.)

High rates of bipolar disorder have been previously reported among the relatives of creative and high-achieving individuals (Coryell et al. 1989; Kyaga et al. 2011, 2013). Mental health conditions that occur among first-degree family members of asymptomatic entrepreneurs may be associated with (or confer) propensities, characteristics, and subthreshold features that are adaptive and advantageous to the asymptomatic entrepreneurs themselves without causing disabilities. This would be parallel to the finding that symptomatic bipolar relatives of symptomatic bipolar probands are also high achievers (Coryell et al. 1989; MacCabe et al. 2010; Verdoux and Bourgeois 1995) and have personality traits that may be advantageous for entrepreneurship (Higier et al. 2014). The cognitive, affective, and behavioral propensities associated with these conditions may foster the pursuit of entrepreneurship under the right environmental circumstances.

6.3 Implications for theory, research, and practice

The findings presented above suggests the possibility of building upon person-centered entrepreneurship research and entrepreneurship mental health and well-being (MWB) studies with a more expansive model that encompasses psychiatric issues. Future research could examine the prevalence of other conditions among entrepreneurs. The relationship between symptom onset and business outcomes such as entrepreneurial entry or exit remains to be clarified. Understanding, exploiting, and managing the specific strengths and vulnerabilities associated with specific psychiatric conditions can contribute to improved entrepreneurship education, executive coaching, business outcomes, and firm survival.

Notes

Hubristic pride measures overly confident beliefs and feelings about one’s self-worth (Tracy et al. 2007).

Improvisational proclivity is theorized to reflect one’s tendency to seek out opportunities that require resourcefulness and creativity (e.g., “I identify ways in which resources can be recombined to produce novel products.”) (Hmieleski and Corbett 2006).

References

Akiskal, K., Savino, M., & Akiskal, H. (2005). Temperament profiles in physicians, lawyers, managers, industrialists, architects, journalists, and artists: a study in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 85(1–2), 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2004.08.003.

Alegría, A. A., Hasin, D. S., Nunes, E. V, Liu, S.-M., Davies, C., Grant, B. F., & Blanco, C. (2010). Comorbidity of generalized anxiety disorder and substance use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(9), 1187-95–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05328gry.

Algorta, G., Youngstrom, E., Phelps, J., Jenkins, M., Youngstrom, J., & Findling, R. (2013). An inexpensive family index of risk for mood issues improves identification of pediatric bipolar disorder. Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029225.

Alloy, L. B., Bender, R. E., Whitehouse, W. G., Wagner, C. A., Liu, R. T., Grant, D. A., et al. (2012). High behavioral approach system (BAS) sensitivity, reward responsiveness, and goal-striving predict first onset of bipolar spectrum disorders: a prospective behavioral high-risk design. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(2), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025877.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5 (5th.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Andreasen, N. C. (1987). Creativity and mental illness: prevalence rates in writers and their first-degree relatives. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(10), 1288–1292. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.144.10.1288.

Andreasen, N. C. (2008). The relationship between creativity and mood disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(2), 251–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2015.10.004.

Bagley, C. (1973). Occupational class and symptoms of depression. Social Science and Medicine, 7(5), 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-7856(73)90042-5.

Bakhshani, N.-M. (2013). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and high risk behaviors. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors and Addiction, 2(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijhrba.12817.

Barlett, D. L., & Steele, J. B. (2004). Howard Hughes: his life and madness (Reissue ed.). New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Baron, R. A., Hmieleski, K. M., & Henry, R. A. (2012). Entrepreneurs’ dispositional positive affect: the potential benefits - and potential costs - of being “up.”. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(3), 310–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.04.002.

Baron, R. A., Tang, J., & Hmieleski, K. M. (2011). The downside of being “up”: entrepreneurs’ dispositional positive affect and firm performance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 5(2), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.109.

Baum, J., & Locke, E. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.587.

Bernardi, S., Faraone, S. V., Cortese, S., Kerridge, B. T., Pallanti, S., Wang, S., & Blanco, C. (2012). The lifetime impact of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Psychological Medicine, 42(4), 875–887. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171100153X.

Biasi, B., Dahl, M., & Moser, P. (2015). Career effects of mental health. Cambridge, MA. doi: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2544251.

Biederman, J., Wilens, T., Mick, E., Milberger, S., Spencer, T. J., & Faraone, S. V. (1995). Psychoactive substance use disorders in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): effects of ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(November), 1652–1658. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.152.11.1652.

Binder, M., & Coad, A. (2013). Life satisfaction and self-employment: a matching approach. Small Business Economics, 40(4), 1009–1033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9413-9.

Birkley, E. L., & Smith, G. (2011). Recent advances in understanding the personality underpinnings of impulsive behavior and their role in risk for addictive behaviors. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 4(4), 215–227.

Brady, K. T., & Sinha, R. (2005). Co-occurring mental and substance use disorders: the neurobiological effects of chronic stress. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1483, 162(8), 1483–1493. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1483.

Brandstätter, H. (2011). Personality aspects of entrepreneurship: a look at five meta-analyses. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(3), 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.07.007.

Brawman-Mintzer, O., Lydiard, R. B., Emmanuel, N., Payeur, R., Johnson, M., Roberts, J., et al. (1993). Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 150(8), 1216–1218. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.150.8.1216.

Burmeister, M. (2015). Genetics of psychiatric disorders, a primer. Focus: the Journal of Lifelong Learning in Psychiatry, 4(3), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1176/foc.4.3.317.

Cardon, M. S., & Patel, P. C. (2015). Is stress worth it? Stress-related health and wealth trade-offs for entrepreneurs. Applied Psychology, 64(2), 379–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12021.

Cardon, M. S., Wincent, J., Singh, J., & Drnovsek, M. (2009). The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 511–532. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2009.40633190.

Caspi, A., & Silva, P. A. (1995). Temperamental qualities at age three predict personality traits in young adulthood: longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Child Development, 66(2), 486–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00885.x.

Clauss, J. A., Avery, S. N., & Blackford, J. U. (2015). The nature of individual differences in inhibited temperament and risk for psychiatric disease: a review and meta-analysis. Progress in Neurobiology, 127, 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.03.001.

Collins, C. J., Hanges, P. J., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of achievement motivation to entrepreneurial behavior: a meta-analysis. Human Performance, 17(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327043HUP1701_5.

Coryell, W., Endicott, J., Keller, M., Andreasen, N., Grove, W., Hirschfeld, R. M. A., & Scheftner, W. (1989). Bipolar affective disorder and high achievement: a familial association. American Journal of Psychiatry, 146(8), 983–988. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.146.8.983.

Dawe, S., Gullo, M. J., & Loxton, N. J. (2004). Reward drive and rash impulsiveness as dimensions of impulsivity: implications for substance misuse. Addictive Behaviors, 29(7), 1389–1405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.004.

de Graaf, R., Bijl, R. V., Smit, F., Vollebergh, W. A. M., & Spijker, J. (2002). Risk factors for 12-month comorbidity of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders: findings from the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(4), 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.620.

Digman, J. M. (1990). Personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology, 41(1), 417–440. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.002221.

Dimic, N., & Orlov, V. (2014). Entrepreneurial tendencies among people with ADHD. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 13(3), 187–204.

Doherty, J. L., & Owen, M. J. (2014). Genomic insights into the overlap between psychiatric disorders: implications for research and clinical practice. Genome Medicine, 6(4), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/gm546.

Drechsler, R., Rizzo, P., & Steinhausen, H. C. (2008). Decision-making on an explicit risk-taking task in preadolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Neural Transmission, 115(2), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-007-0814-5.

Drucker, P. F. (1998). The discipline of innovation. Harvard Business Review, 76(6), 149–157.

Dyer, J. H., Gregersen, H. B., & Christensen, C. (2008). Entrepreneur behaviors, opportunity recognition, and the origins of innovative ventures. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(4), 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.59.

Dyson, M. W., Olino, T. M., Durbin, C. E., Goldsmith, H. H., Bufferd, S. J., Miller, A. R., & Klein, D. N. (2015). The structural and rank-order stability of temperament in young children based on a laboratory-observational measure. Psychological Assessment, 27(4), 1388–1401. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000104.

Faraone, S. V., Biederman, J., & Wozniak, J. (2012). Examining the comorbidity between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar I disorder: a meta-analysis of family genetic studies. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(12), 1256–1266. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010087.

Feldstein, S. W., & Miller, W. R. (2006). Substance use and risk-taking among adolescents. Journal of Mental Health, 15(6), 633–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230600998896.

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class: and how it is transforming community and everyday life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Freeman, M. A. (2013). Achievement, innovation, and leadership in the affective spectrum. 166th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. San Francisco.

Fuller, B., & Marler, L. E. (2009). Change driven by nature: a meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.05.008.

Furnham, A. (1986). Response bias, social desirability and dissimulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 7(3), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(86)90014-0.

Gartner, J. D. (2008). The hypomanic edge: the link between (a little) craziness and (a lot of) success in America. Simon and Schuster.

Ghaemi, S. (2011). A first-rate madness: uncovering the links between leadership and mental illness. New York: Penguin Press.

Goekoop, R., & Goekoop, J. G. (2014). A network view on psychiatric disorders: network clusters of symptoms as elementary syndromes of psychopathology. PLoS One, 9(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112734.

Gorgievski, M. J., Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., van der Veen, H. B., & Giesen, C. W. M. (2010). Financial problems and psychological distress: investigating reciprocal effects among business owners. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(2), 513–530. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X434032.

Gorgievski, M. J., & Stephan, U. (2016). Advancing the psychology of entrepreneurship: a review of the psychological literature and an introduction. Applied Psychology, 65(3), 437–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12073.

Gratten, J., Wray, N. R., Keller, M. C., & Visscher, P. M. (2014). Large-scale genomics unveils the genetic architecture of psychiatric disorders. Nature Neuroscience, 17(6), 782–790. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3708.

Gruber, J., & Johnson, S. L. (2009). Positive emotional traits and ambitious goals among people at risk for mania: the need for specificity. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 2(2), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2009.2.2.176.

Hausser, J. A., Mojzisch, A., Niesel, M., & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2010). Ten years on: a review of recent research on the Job Demand-Control (-Support) model and psychological well-being. Work and Stress, 24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678371003683747.

Healey, D. M., & Rucklidge, J. J. (2006). An investigation into the relationship among ADHD symptomatology, creativity, and neuropsychological functioning in children. Child Neuropsychology, 12(6), 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297040600806086.

Healey, D. M., & Rucklidge, J. J. (2008). The relationship between ADHD and creativity. The ADHD Report, 16(3), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1521/adhd.2008.16.3.1.

Hershman, D., & Lieb, J. (1994). A brotherhood of Tyrants: manic depression & absolute power. Amherst, N.Y: Prometheus Books.

Hershman, D., & McFarlane, A. (2002). Hershman & McFarlane children act handbook. Bristol: Jordan.

Higier, R. G., Jimenez, A. M., Hultman, C. M., Borg, J., Roman, C., Kizling, I., et al. (2014). Enhanced neurocognitive functioning and positive temperament in twins discordant for bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(11), 1191–1198. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13121683.

Hmieleski, K., & Corbett, A. (2006). Proclivity for improvisation as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Managment, 44(1), 45–63.

Holmes, M. K., Bearden, C. E., Barguil, M., Fonseca, M., Monkul, E. S., Nery, F. G., et al. (2009). Conceptualizing impulsivity and risk taking in bipolar disorder: importance of history of alcohol abuse. Bipolar Disorders, 11(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00657.x.

Hunt, M., Auriemma, J., & Cashaw, A. C. A. (2003). Self-report bias and underreporting of depression on the BDI-II. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80(1), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_10.

Jamal, M. (1991). Job stress, satisfaction, and mental health: an empirical examination of self-employed and non-self-employed Canadians. Journal of Small Business Management, 35(4), 48–58.

Jamal, M., & Mitchell, V. (1980). Work, nonwork, and mental health: a model and a test. Industrial Relations, 19(1), 88–93.

Jamison, K. R. (1995). Manic-depressive illness and creativity. Scientific American, 272(2), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0295-62.

Jang, S.-Y., Jang, S.-I., Bae, H.-C., Shin, J., & Park, E.-C. (2015). Precarious employment and new-onset severe depressive symptoms: a population-based prospective study in South Korea. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 41(4), 329–337. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3498.

Johnson, S. L. (2004). Defining bipolar disorder. In Psychological treatment of bipolar disorder (pp. 3–16). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Johnson, S. L., Eisner, L. R., & Carver, C. S. (2009). Elevated expectancies among persons diagnosed with bipolar disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 48(2), 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466509X414655.

Johnson, S. L., Freeman, M. A., & Staudenmaier, P. J. (2015a). Manic tendencies are not related to being an entrepreneur, intending to become an entrepreneur, or succeeding as an entrepreneur. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173(March), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.049.

Johnson, S. L., Freeman, M. A., & Staudenmaier, P. J. (2015b). Mania, risk, overconfidence, and ambition. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(7), 611–621.

Johnson, S. L., Madole, J., & Freeman, M. A. (2018). Mania risk and entrepreneurship: overlapping personality traits. Academy of Management Perspectives.

Johnson, S. L., Murray, G., Hou, S., Staudenmaier, P. J., Freeman, M. A., & Michalak, E. E. (2015). Creativity is linked to ambition across the bipolar spectrum. Journal of Affective Disorders, 178, 160–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.021.

Karlsson, J. (1970). Genetic association of giftedness and creativity with schizophrenia. Hereditas, 66, 177–182.

Kawakami, N., Iwata, N., Tanigawa, T., Oga, H., Araki, S., Fujihara, S., & Kitamura, T. (1996). Prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in a working population in Japan. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 38(9), 899–905. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-199609000-00012.

Kessler, R. C., Akiskal, H. S., Ames, M., Birnbaum, H., Greenberg, P., & Hirschfeld, R. M. a, et al. (2006). Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of U.S. workers. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(9), 1561–1568. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1561.

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617.

Kooij, S., Marije Boonstra, A., Swinkels, S. H. N., Bekker, E. M., De Noord, I., & Buitelaar, J. K. (2008). Reliability, validity, and utility of instruments for self-report and informant report concerning symptoms of ADHD in adult patients. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11(4), 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054707299367.

Koppe, K., & Rothermund, K. (2017). Let it go: depression facilitates disengagement from unattainable goals. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 54, 278–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.10.003.

Kreek, M. J., Nielsen, D. A., Butelman, E. R., & LaForge, K. S. (2005). Genetic influences on impulsivity, risk taking, stress responsivity and vulnerability to drug abuse and addiction. Nature Neuroscience, 8(11), 1450–1457. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1583.

Kyaga, S., Landén, M., Boman, M., Hultman, C. M., Långström, N., & Lichtenstein, P. (2013). Mental illness, suicide and creativity: 40-year prospective total population study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(1), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.010.

Kyaga, S., Lichtenstein, P., Boman, M., Hultman, C., Långström, N., & Landén, M. (2011). Creativity and mental disorder: family study of 300 000 people with severe mental disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(5), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085316.

Lee, S. S., Humphreys, K. L., Flory, K., Liu, R., & Glass, K. (2011). Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 328–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.006.

Leignel, S., Schuster, J. P., Hoertel, N., Poulain, X., & Limosin, F. (2014). Mental health and substance use among self-employed lawyers and pharmacists. Occupational Medicine, 64(3), 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqt173.

Lejuez, C. W., Magidson, J. F., Mitchell, S. H., Sinha, R., Stevens, M. C., & De Wit, H. (2010). Behavioral and biological indicators of impulsivity in the development of alcohol use, problems, and disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(8), 1334–1345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01217.x.

Leutner, F., Ahmetoglu, G., Akhtar, R., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2014). The relationship between the entrepreneurial personality and the Big Five personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 63(June), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.042.

Lewin-Epstein, N., & Yuchtman-Yaar, E. (1991). Health risks of self-employment. Work and Occupations, 18(3), 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888491018003003.

Lin, S. K., Lee, C. H., Pan, C. H., & Hu, W. H. (2003). Comparison of the prevalence of substance use and psychiatric disorders between government- and self-employed commercial drivers. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 57(4), 425–431. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01142.x.

Ludwig, A. M. (1992). Creative achievement and psychopathology: comparison among professions. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 46(3), 330–356. https://doi.org/10.1680/udap.2010.163.

MacCabe, J. H., Lambe, M. P., Cnattingius, S., Sham, P. C., David, A. S., Reichenberg, A., et al. (2010). Excellent school performance at age 16 and risk of adult bipolar disorder: national cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry: the Journal of Mental Science, 196(2), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.060368.

MacCrimmon, K. R., & Wehrung, D. A. (1990). Characteristics of risk taking executives. Management Science, 36(4), 422–435. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.36.4.422.

MacDonald, Z., & Pudney, S. (2000). Illicit drug use, unemployment, and occupational attainment. Journal of Health Economics, 19(6), 1089–1115. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-6296(00)00056-4.

Machado-Vieira, R., Luckenbaugh, D. A., Ballard, E. D., Henter, I. D., Tohen, M., Suppes, T., & Zarate, C. A. (2017). Increased activity or energy as a primary criterion for the diagnosis of bipolar mania in DSM-5: findings from the STEP-BD study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15091132.

Mannuzza, S., Klein, R. G., Bessler, A., Malloy, P., & LaPadula, M. (1993). Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50(7), 565–576. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820190067007.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (2008). Empirical and theoretical status of the five-factor model of personality traits. The SAGE Handbook of Personality theory and assessment, 1, 273–294. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849200462NV-1.

McElroy, S. L., Altshuler, L. L., Suppes, T., Keck Jr., P. E., Frye, M. A., Denicoff, K. D., et al. (2001). Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(3), 420–426. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.420.

McGough, J. J., Smalley, S. L., McCracken, J. T., Yang, M., Del’Homme, M., Lynn, D. E., & Loo, S. (2005). Psychiatric comorbidity in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings from multiplex families. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(9), 1621–1627. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1621.

Merikangas, K., Akiskal, H., Angst, J., Greenberg, P., Hirschfeld, R., Petukhova, M., & Kessler, R. (2007). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(5), 543–552. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543.

Moeller, F. G., Barratt, E. S., Dougherty, D. M., Schmitz, J. M., & Swann, A. C. (2001). Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(11), 1783–1793. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783.

Monnelly, E., Woodruff, R., & Robins, L. (1974). Manic-depressive illness and social achievement in a public hospital sample. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 50(3), 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1974.tb08217.x.

Murdoch, A., Haynie, J., & Schindehutte, M. (2007). Serial entrepreneurs: entrepreneuring behaviors as psychological addiction (summary). Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 27(6).

Neely, A., & Hii, J. (1998). Innovation and business performance: a literature review. The Judge Institute of Management Studies, University of Cambridge.

Nicolaou, N., Shane, S., Adi, G., Mangino, M., & Harris, J. (2011). A polymorphism associated with entrepreneurship: evidence from dopamine receptor candidate genes. Small Business Economics, 36(2), 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9308-1.

O’Farrell, T., & Maisto, S. (1987). The utility of self-report and biological measures of alcohol consumption in alcoholism treatment outcome studies. Advances in Behaviour Research & Therapy, 9(2–3), 91–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(87)90010-5.

Obschonka, M., Schmitt-Rodermund, E., Silbereisen, R. K., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2013). The regional distribution and correlates of an entrepreneurship-prone personality profile in the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom: a socioecological perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(1), 104–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032275.

Obschonka, M., & Stuetzer, M. (2017). Integrating psychological approaches to entrepreneurship: the Entrepreneurial Personality System (EPS). Small Business Economics, 49(1), 203–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9821-y.

Organ, D., O’Flaherty, B., & Bogue, J. (2016). ADHD and fear of failure: an empirical study exploring their link to new venture performance. In R&D Management Conference 2016 “From Science to Society: Innovation and Value Creation” (pp. 1–11). Cambridge, UK.

Parslow, R. A., Jorm, A. F., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., Strazdins, L., & D’Souza, R. M. (2004). The associations between work stress and mental health: a comparison of organizationally employed and self-employed workers. Work and Stress, 18(3), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/14749730412331318649.

Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2011). Negative emotions of an entrepreneurial career: self-employment and regulatory coping behaviors. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(2), 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.08.002.

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Post, F. (1994). Creativity and psychopathology. A study of 291 world-famous men. British Journal of Psychiatry, 164(July), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.165.1.22.

Post, F. (1996). Verbal creativity, depression and alcoholism. An investigation of one hundred American and British writers. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 168(5), 545–555. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.168.5.545.

Rahim, A. (1996). Stress, strain, and their moderators: an empirical comparison of entrepreneurs and managers. Journal of Small Business Management, 34(1), 46.

Rauch, A., & Frese, M. (2007). Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: a meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 16(4), 353–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320701595438.

Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G. T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: an assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00308.x.

Reddy, L. F., Lee, J., Davis, M. C., Altshuler, L., Glahn, D. C., Miklowitz, D. J., & Green, M. F. (2014). Impulsivity and risk taking in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(2), 456–463. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.218.

Richards, R., Kinney, D. K., Lunde, I., Benet, M., & Merzel, P. (1988). Creativity in manic-depressives, cyclothymes, their normal relatives, and control subjects. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(3), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.97.3.281.

Saarni, S. I., Saarni, E. S., & Saarni, H. (2008). Quality of life, work ability, and self employment: a population survey of entrepreneurs, farmers, and salary earners. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 65(2), 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2007.033423.

Sachs, G. S., Baldassano, C. F., Truman, C. J., & Guille, C. (2000). Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with early- and late-onset bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(3), 466–468. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.466.

Santosa, C. M., Strong, C. M., Nowakowska, C., Wang, P. W., Rennicke, C. M., & Ketter, T. A. (2007). Enhanced creativity in bipolar disorder patients: a controlled study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 100(1–3), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.013.

Schatz, D. B., & Rostain, A. L. (2006). ADHD with comorbid anxiety. Journal of Attention Disorders, 10(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054706286698.

Seibert, S. E., Crant, J. M., & Kraimer, M. L. (1999). Proactive personality and career success. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(3), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.416.

Shoham, R., Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S., Aloni, H., Yaniv, I., & Pollak, Y. (2016). ADHD-associated risk taking is linked to exaggerated views of the benefits of positive outcomes. Scientific Reports, 6(Oct), 34833. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep34833.

Simeonova, D. I., Chang, K. D., Strong, C., & Ketter, T. A. (2005). Creativity in familial bipolar disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 39(6), 623–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.01.005.

Simon, N. M., Otto, M. W., Wisniewski, S. R., Fossey, M., Sagduyu, K., Frank, E., et al. (2004). Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(12), 2222–2229. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2222.

Spivack, A. J., McKelvie, A., & Haynie, J. M. (2014). Habitual entrepreneurs: possible cases of entrepreneurship addiction? Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 651–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.11.002.

Stephan, U., & Roesler, U. (2010). Health of entrepreneurs versus employees in a national representative sample. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 717–738. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909x472067.

Stewart, W., & Roth, P. (2001). Risk propensity differences between entrepreneurs and managers: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.1.145.

Strakowski, S. M., Fleck, D. E., DelBello, M. P., Adler, C. M., Shear, P. K., Kotwal, R., & Arndt, S. (2010). Impulsivity across the course of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 12(3), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00806.x.

Sullivan, P. F., Agrawal, A., Bulik, C. M., Andreassen, O. A., Børglum, A. D., Breen, G., et al. (2017). Psychiatric genomics: an update and an agenda. American Journal of Psychiatry. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17030283.

Sullivan, P. F., Daly, M. J., & O’Donovan, M. (2012). Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: the emerging picture and its implications. Nature Reviews Genetics, 13(8), 537–551. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3240.

Swann, A., Anderson, J., Dougherty, D., & Moeller, G. (2001). Measurement of inter-episode impulsivity in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research, 101(2), 195–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00249-3.

Takayanagi, Y., Spira, A. P., Roth, K. B., Gallo, J. J., Eaton, W. W., & Mojtabai, R. (2014). Accuracy of reports of lifetime mental and physical disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(3), 273. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3579.

Thurik, R., Khedhaouria, A., Torrès, O., & Verheul, I. (2016). ADHD symptoms and entrepreneurial orientation of small firm owners. Applied Psychology, 65(3), 568–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12062.

Torske, M. O., Bjørngaard, J. H., Hilt, B., Glasscock, D., & Krokstad, S. (2016). Farmers’ mental health: a longitudinal sibling comparison—the HUNT study, Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 42(6), 547–556. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3595.