Abstract

Is firm growth more persistent for young or old firms? Theory gives us no clear guidance, and previous empirical investigations have been hampered by a lack of detailed data on firm age, as well as a non-representative coverage of young firms. We overcome these shortcomings using a rich dataset on all limited liability firms in Sweden during 1998–2008, covering firms of all ages and information on registered start year. Sales growth for new ventures is characterized by positive persistence, which quickly turns negative as firms get older. Young firms are more likely to have two consecutive periods of positive growth. While new firms experience an early burst of sustained growth, older firms have more erratic growth paths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In fact, this was already emphasized by Fizaine (1968) when investigating the growth of establishments in the French region of Bouches-du-Rhône.

This latter approach to determine a firm’s age is still highly accurate, but it means that for older firms our age variable cannot account for the possibility that a firm has changed the periodicity of their split financial year and consequentially measure age with a possible error of at most ±1 year.

These integer restrictions affecting employment growth data are particularly problematic for the computation of quantile regressions. In a further robustness analysis, however, we apply OLS regressions to employment growth data, and the results obtained were similar in that the autocorrelation coefficient is highest in the early years and quickly decreases (although for most ages, the autocorrelation coefficient was not clearly negative but close to zero).

For simplicity, we overlook the fact that the exponential is a continuous distribution whereas our age data is discrete.

In 1975, Sweden increase the minimum amount of capital required to start an incorporation from 5000 SEK to 50,000 SEK. This amount was increased once more in 1995 from 50,000 SEK to 100,000 SEK. Firms that registered prior to January 1 in 1995 were exempt from increasing the equity to 100,000 SEK until 1998. The reason we still see an increase in 1995 (until the last of July) is because a newly registered company had a 6-month period to have a first statutory meeting of the board. This means that a firm could have a registration date in June of 1995, but still qualify for 50,000 SEK in equity. As for the increase observed in the month of July, it is due to the registration of a large number of so-called shelf-companies.

The mode is not reported here, because the distribution is multimodal.

Growth is calculated as a function of both size at time t, and size at time t-1; hence, the first observation for growth is in year 2.

Since the distribution of age is skewed, using the mean instead of the median could be problematic if there are firms with high age in a grid-box that otherwise contains mostly young firms.

Since median age is computed with different numbers of observations over the grid, the densities in Figure 6 are therefore weighted giving more weights to cells in the grid that contains more observations. The weights are constructed by counting the number of observations in each grid-box over which the median age is computed. The resulting counts are then entered as analytical weights [aweights] in the contour plot.

All median regression estimations are performed in Stata using the qreg with the vce(robust) option. Bootstrapping our standard errors was not a viable option due to the numerous regressions undertaken at each age.

Since we are interested in the effect on growth rates, we consider the marginal effect on growth t from a unit change in growth t − 1 instead of the elasticity defined as the percentage effect change on size i , t /size i , t − 1 from a percentage change in size i , t − 1/size i , t − 2.

Excluding the age variable from the regression doubles the estimated coefficient on initial growth (not reported). Still not a strikingly high level of autocorrelation, but it suggests some form of relationship between the two variables.

Strictly speaking younger than 5 years are firms between 2 and 4 years old since the youngest firm with at least two observed consecutive growth rates is 2 years old (counted as 0 in 2006 when it was founded).

All results are available from the authors upon request.

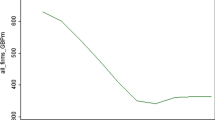

In 2008, we observed in Figure 3 that the growth dynamic of young firms between 2 and 4 years were characterized by positive autocorrelation. Following the peak of dot-com crises in 2001, positive autocorrelation could only be observed for firms of 2 years. For every other year, positive autocorrelation rates were observed for the median firm the first 2 or 3 years in its life.

For 2008 autocorrelation turned negative and significant for firms of 16 years and remained negative until firms aged 21 years, but for 2002, the negative period took place between ages 9 and 13.

Note however that notions of an “optimal size” for firms have been repeatedly rejected in the empirical literature (Coad 2009, pp100–101).

References

Almus, M., & Nerlinger, E. (2000). Testing "Gibrat's law" for young firms—empirical results for West Germany. Small Business Economics, 15(1), 1–12. doi:10.1023/a:1026512005921.

Anyadike-Danes M., Hart M. (2014). All grown up? The fate after 15 years of the quarter of a million UK firms born in 1998. Sept 14th, Mimeo.

Arrow, K. J. (1962). The economic implications of learning by doing. Review of Economic Studies, 29, 155–173. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-15430-2_11.

Audretsch, D. B. (1995). Innovation, growth and survival. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13, 441–457. doi:10.1016/0167-7187(95)00499-8.

Bamford, C. E., Dean, T. J., & Douglas, T. J. (2004). The temporal nature of growth determinants in new bank foundings: Implications for new venture research design. Journal of Business Venturing, 19, 899–919. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2003.05.001.

Barba Navaretti, G., Castellani, D., & Pieri, F. (2014). Age and firm growth: evidence from three European countries. Small Business Economics, 43(4), 823–837. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9564-6.

Barron, D. N., West, E., & Hannan, M. T. (1994). A time to grow and a time to die: growth and mortality of credit unions in New York, 1914-1990. American Journal of Sociology, 100(2), 381–421. doi:10.1086/230541.

Bettis, R., Gambardella, A., Helfat, C., & Mitchell, W. (2014). Quantitative empirical analysis in strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 35(7), 949–953. doi:10.1002/smj.2278.

Bianchini, S., Bottazzi, G., & Tamagni, F. (2016). What does (not) characterize persistent corporate high-growth? Small Business Economics, 48(3), 633–656 doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9790-1.

Bottazzi, G., & Secchi, A. (2006). Explaining the distribution of firm growth rates. RAND Journal of Economics, 37(2), 235–256. doi:10.1111/j.1756-2171.2006.tb00014.x.

Bottazzi, G., Coad, A., Jacoby, N., & Secchi, A. (2011). Corporate growth and industrial dynamics: evidence from French manufacturing. Applied Economics, 43(1), 103–116. doi:10.1080/00036840802400454.

Cabral, L. (1995). Sunk costs, firm size and firm growth. Journal of Industrial Economics, 43(2), 161–172. doi:10.2307/2950479.

Capasso, M., Cefis, E., & Frenken, K. (2014). On the existence of persistently outperforming firms. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23(4), 997–1036. doi:10.1093/icc/dtt034.

Caves, R. E. (1998). Industrial organization and new findings on the turnover and mobility of firms. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(4), 1947–1982 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2565044.

Chang, Y., Gomes, J. F., & Schorfheide, F. (2002). Learning-by-doing as a propagation mechanism. American Economic Review, 92, 1498–1520. doi:10.2139/ssrn.277131.

Chesher, A. (1979). Testing the law of proportionate effect. Journal of Industrial Economics, 27(4), 403–411.

Coad, A. (2007). A closer look at serial growth rate correlation. Review of Industrial Organization, 31, 69–82. doi:10.1007/s11151-007-9135-y.

Coad A., (2009). The growth of firms: a survey of theories and empirical evidence. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA.

Coad, A, & Planck, M. (2012). Firms as bundles of discrete resources – towards an explanation of the exponential distribution of firm growth rates. Eastern Economic Journal, 38, 189–209.

Coad, A. (2017). Firm age: a survey. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, forthcoming. doi:10.1007/s00191-016-0486-0.

Coad, A., & Hölzl, W. (2009). On the autocorrelation of growth rates. Journal of Industry Competition and Trade, 9(2), 139–166. doi:10.1007/s10842-009-0048-3.

Coad, A., & Rao, R. (2008). Innovation and firm growth in high-tech sectors: a quantile regression approach. Research Policy, 37(4), 633–648. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2008.01.003.

Coad, A., Frankish, J., Roberts, R., & Storey, D. (2013a). Growth paths and survival chances: an application of Gambler’s ruin theory. Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 615–632. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.06.002.

Coad, A., Segarra, A., & Teruel, M. (2013b). Like milk or wine: does firm performance improve with age? Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 24, 173–189. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1815028.

Coad, A., Daunfeldt, S.-O., Hölzl, W., Johansson, D., & Nightingale, P. (2014). High-growth firms: Introduction to a special issue. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23, 91–112. doi:10.1093/icc/dtt052.

Coad, A., Frankish, J. S., Roberts, R. G., & Storey, D. J. (2016). Predicting new venture survival and growth: does the fog lift? Small Business Economics, 47, 217–241. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2408027.

Collier, B. L., Haughwout, A. F., Kunreuther, H. C., Michel-Kerjan, E. O., & Stewart, M. A. (2016). Firm age and size and the financial management of infrequent shocks (No. w22612). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Daunfeldt, S.-O., & Halvarsson, D. (2015). Are high-growth firms one hit wonders? Evidence from Sweden. Small Business Economics, 44(2), 361–383. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9599-8.

Daunfeldt, S.-O., Elert, N., & Johansson, D. (2014). Economic contribution of high-growth firms: do policy implications depend on the choice of growth indicator? Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 14, 337–365. doi:10.1007/s10842-013-0168-7.

Davidsson, P., Steffens, P., & Fitzsimmons, J. (2009). Growing profitable or growing from profits: putting the horse in front of the cart? Journal of Business Venturing, 24(4), 388–406. doi:10.4337/9780857933614.00017.

Decker, R., Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R., & Miranda, J. (2014). The role of entrepreneurship in US job creation and economic dynamism. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 3–24. doi:10.1257/jep.28.3.3.

Delmar, F. (1997). ‘Measuring growth: methodological considerations and empirical results’. In R. Donckels, A. Miettinen (Eds.), Entrepreneurship and SME research: on its way to the next millennium, (pp. 190–216). Aldershot, VA: Avebury

Delmar, F., Davidsson, P., & Gartner, W. B. (2003). Arriving at the high-growth firm. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 189–216. doi:10.4337/9781781009949.00018.

Denrell, J., Fang, C., Liu, C., (2015). Chance explanations in the management sciences. Organization Science, in press.

Dunne, P., & Hughes, A. (1994). Age, size, growth and survival: UK companies in the 1980s. Journal of Industrial Economics 42(2), 115–140.

Dunne, T., Roberts, M., & Samuelson, L. (1989). The growth and failure of US manufacturing plants. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4), 671–698. doi:10.2307/2937862.

Evans, D. S. (1987). The relationship between firm growth, size and age: estimates for 100 manufacturing industries. Journal of Industrial Economics, 35, 567–581. doi:10.2307/2098588.

Fizaine, F. (1968). Analyse statistique de la croissance des entreprises selon l’âge et la taille. Revue d’économie Politique, 78, 606–620.

Folta, T. B., Delmar, F., & Wennberg, K. (2010). Hybrid entrepreneurship. Management Science, 56(2), 253–269. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1090.1094.

Fotopoulos, G., & Louri, H. (2004). Firm growth and FDI: Are multinationals stimulating local industrial development? Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 4(3), 163–189. doi:10.1023/b:jict.0000047300.88236.f1.

Garnsey, E. (1998). A theory of the early growth of the firm. Industrial and Corporate Change, 7(3), 523–556. doi:10.1093/icc/7.3.523.

Garnsey, E., & Heffernan, P. (2005). Growth setbacks in new firms. Futures, 37(7), 675–697. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1923138.

Geroski, P. A. (2000). The growth of firms in theory and in practice. In N. Foss & V. Mahnke (Eds.), Competence, governance and entrepreneurship (pp. 168–186). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gibrat, R. (1931). Les inégalités économiques. Paris: Librairie du Receuil Sirey.

Gilbert, B. A., McDougall, P. P., & Audretsch, D. B. (2006). New venture growth: a review and extension. Journal of Management, 32(6), 926–950. doi:10.1177/0149206306293860.

Goddard, J., Wilson, J., & Blandon, P. (2002). Panel tests of Gibrat's law for Japanese manufacturing. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 20, 415–433.

Greiner, L. E. (1998). Evolution and revolution as organizations grow (pp. 55–67). Harvard Business Review. doi:10.1016/s0167-7187(00)00085-0.

Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R. S., & Miranda, J. (2013). Who creates jobs? Small versus large versus young. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 347–361. doi:10.1162/rest_a_00288.

Headd, B., & Kirchhoff, B. (2009). The growth, decline and survival of small businesses: an exploratory study of life cycles. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(4), 531–550. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627x.2009.00282.x.

Helfat, C. E. (2007). Stylized facts, empirical research and theory development in management. Strategic Organization, 5(2), 185–192. doi:10.1177/1476127007077559.

Hölzl, W. (2014). Persistence, survival, and growth: a closer look at 20 years of fast-growing firms in Austria. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23(1), 199–231.

Huergo, E., & Jaumandreu, J. (2004). How does probability of innovation change with firm age? Small Business Economics, 22, 193–207. doi:10.1023/b:sbej.0000022220.07366.b5.

Ijiri, Y., & Simon, H. A. (1967). A model of business firm growth. Econometrica, 35(2), 348–355.

Lawless, M. (2014). Age or size? Contributions to job creation. Small Business Economics, 42, 815–830. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9513-9.

Levinthal, D. A. (1991). Random walks and organizational mortality. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 397–420. doi:10.2307/2393202.

Lotti, F., Santarelli, E., & Vivarelli, M. (2003). Does Gibrat's law hold among young, small firms? Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 13(3), 213–235. doi:10.1007/s00191-003-0153-0.

Lotti, F., Santarelli, E., & Vivarelli, M. (2009). Defending Gibrat's law as a long-run regularity. Small Business Economics, 32, 31–44. doi:10.1007/s11187-007-9071-0.

McKelvie, A., & Wiklund, J. (2010). Advancing firm growth research: a focus on growth mode instead of growth rate. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(2), 261–288. doi:10.4337/9780857933614.00014.

Parker, S. C. (2004). The economics of self-employment and entrepreneurship. Cambridge University Press.

Parker, S. C., Storey, D. J., & van Witteloostuijn, A. (2010). What happens to gazelles? The importance of dynamic management strategy. Small Business Economics, 35, 203–226. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9250-2.

Phillips, B. D., & Kirchhoff, B. A. (1989). Formation, growth and survival; small firm dynamics in the US economy. Small Business Economics, 1, 65–74. doi:10.1007/bf00389917.

Reichstein, T., Dahl, M. S., Ebersberger, B., & Jensen, M. B. (2010). The devil dwells in the tails: a quantile regression approach to firm growth. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 20(2), 219–231. doi:10.1007/s00191-009-0152-x.

Robson, P., & Bennett, R. (2000). SME growth: the relationship with business advice and external collaboration. Small Business Economics, 15(3), 193–208. doi:10.1023/a:1008129012953.

Shepherd, D., & Wiklund, J. (2009). Are we comparing apples with apples or apples with oranges? Appropriateness of knowledge accumulation across growth studies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(1), 105–123. doi:10.4337/9780857933614.00013.

Singh, A., & Whittington, G. (1975). The size and growth of firms. Review of Economic Studies, 42(1), 15–26.

Sorensen, J. B., & Stuart, T. E. (2000). Aging, obsolescence, and organizational innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45, 81–112. doi:10.2307/2666980.

Stanley, M. H. R., Amaral, L. A. N., Buldyrev, S. V., Havlin, S., Leschhorn, H., Maass, P., Salinger, M. A., & Stanley, H. E. (1996). Scaling behavior in the growth of companies. Nature, 379, 804–806. doi:10.1038/379804a0.

Stinchcombe, A. (1965). Social structure and organizations. In J. G. March (Ed.), Handbook of organizations (pp. 142–193). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Sutton, J. (1997). Gibrat’s legacy. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(1), 40–59 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2729692.

Tornqvist, L., Vartia, P., & Vartia, Y. O. (1985). How should relative changes be measured? American Statistician, 39(1), 43–46. doi:10.2307/2683905.

Yasuda, T. (2005). Firm growth, size, age and behaviour in Japanese manufacturing. Small Business Economics, 24(1), 1–15. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-7568-y.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Michael Anyadike-Danes, Jean Bonnet, Anders “Billy” Bornhall, Martin Carree, Marc Cowling, Michaela Niefert, the editor (Christina Guenther), two anonymous reviewers, and participants at ZEW (Mannheim), BCERC 2014 (London, Ontario) and Conférence Forum Innovation VI (Paris, France) for valuable comments and suggestions. The usual caveat applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coad, A., Daunfeldt, SO. & Halvarsson, D. Bursting into life: firm growth and growth persistence by age. Small Bus Econ 50, 55–75 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9872-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9872-8

Keywords

- Firm age

- Growth rate autocorrelation

- Sales growth

- Growth persistence

- Learning-by-doing

- Minimum efficient scale

- Growth paths