Abstract

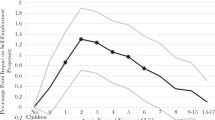

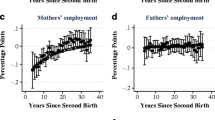

This paper studies the effect of children on the likelihood of self-employment. Having children can change preferences that are central to the decision whether to be self-employed. On the one hand, individuals’ preference for autonomy and flexibility increases when having children, which increases the willingness to be self-employed. On the other hand, having children entails a responsibility over someone else, which increases individual risk aversion and decreases the willingness to be self-employed. Using a pooled cross section of 26 years from the General Social Survey, instrumental variable estimates indicate that, in the USA, having children under the age of 18 in the household decreases the likelihood of being self-employed by 11 % (i.e., the responsibility effect dominates). This effect is considerable as a child decreases the probability of self-employment more than the increase associated with being raised by a self-employed father—one of the main determinants of self-employment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Parker (2004) also suggests that family funding may affect the decision to be self-employed, as family funds represent a big portion of all private loans. Yet, the evidence of a direct link between family funds and self-employment is still not conclusive. In this paper, I briefly discuss the role of family funding in the context of the USA.

In order to understand the mediating roles of concerns for responsibility and autonomy in the effect of children on the likelihood of being self-employed, one would ideally have measures of preferences toward risk and autonomy. Yet, in the absence of such measures, the analysis presented here is restricted to an estimation of the overall effect. This estimation is informative, nonetheless, as we expect the responsibility and autonomy effects of children in the likelihood of self-employment going in opposite directions. First, I explore whether children significantly change the likelihood of being self-employed. And then, I use the results of the estimation of the overall effect to infer which of the proposed mechanisms empirically dominates.

I chose the retail sector as the base sector given that its rate of self-employment resembles the aggregate one and is a sector which is observed frequently enough in the sample.

See Ahmad and Hoffman (2007) for a discussion on recent efforts made toward generating comparable measures of entrepreneurship.

Early definitions of entrepreneurship stressed on (i) the ability to assume risks and (ii) the enjoyment of profits when enterprises succeed. These are characteristics shared between the self-employed and entrepreneurs, including the “transformational” entrepreneurs that Lerner and Schoar (2010) refers to.

In a population where remedial self-employment is typical, i.e., with a higher prevalence of poverty, the effect could easily be the opposite to the one we find here. That is, becoming a parent could increase the chances of self-employment as a response to an increased pressure for gains when the chances of subsistence being at stake are increased.

Note, however, that a macro analysis for these variables is harder given that the definitions and methods vary between papers.

One should highlight that though a consensus reflects a majority, even the significance of these variables continue to be disputed e.g Eckel and Grossman (2008).

However, this does not mean that they have not gained in flexibility even if the total hours usually increase.

The dataset contains less years than the time-frame because the survey was not conducted in all the years. Additionally, years between 1972 and 1974 are dropped. Though those years are available they do not contain information on some of the variables used. One observation reporting 64 siblings is also dropped.

The dataset provides probabilistic weights (WTSSALL) and cluster information (SAMPCODE) which are used in all estimations, even though the results found are robust to not using the weights. Robustness checks, available for the interested reader, use samples that further exclude individuals: temporarily not working, keeping the house, unemployed, and laid off but not self-employed. Results are robust in sign and significance to these restrictions. Moreover, the magnitude of the effect is fairly robust to using a more restrictive sample.

Additionally, the results prove to be robust to the exclusion of this variable using the correspondingly bigger sample. This suggests that missing the information of this variable is not related to being self-employed.

Long-term effects of the recession in self-employment are still unclear.

A few observations report a high number of children or siblings. The results do not change significantly when excluding those observations.

It is worth noting that, until 2006 the survey was only conducted in English. After 2006 they introduced the possibility of answering the survey in Spanish.

This classification is instrumental to my exposition. Specifically, it highlights whether an individual has children and whether they live with a partner.

Even though this assumption seems somewhat strong, as was pointed out by one of the referees, to the best of my knowledge there is no reference in the literature that suggests parents may enjoy parenthood differently when doing similar jobs for themselves or others. It may be that they might spend different amounts of time with their children if self-employed, but conditional on the time working, children should bring the same level of enjoyment in one’s life.

A referee pointed out to the possibility that reverse causality might also happen between preferences and the number of children. On the one hand, indeed, there is some evidence that high risk tolerant women are more likely to delay marriage, and high risk tolerance increases fertility for the young but high risk tolerance decreases fertility for the old (Schmidt 2008). The relevant question in our case, however, is whether the number of siblings affect risk preferences. While the evidence in this regard is scarce, there are reasons to believe that the effect is rather small. For example, Guiso and Paiella (2008) find that siblings have no significant effects on risk aversion, and Eckel and Grossman (2008) finds that birth order has no effect on risk aversion. On the other hand, to the best of my knowledge there is no research studying the effects of siblings or sibling order on the preferences for autonomy.

Indeed, anecdotal evidence suggests that the capacity to underestimate the effect of children on individual preferences is fairly high.

Some papers, including (Hundley 2006; Hout and Rosen 2000), include the variable of number of brothers but do not include the number of children. Therefore, any significant effects found, for example in Hundley (2006), may result from the number of siblings working as a proxy for the number of children. Moreover, these papers do not discuss in detail the criteria to include this variable.

According to the World Development Indicators of the World Bank, by 2012 the average fertility rate in the high income countries was 1.7, 2.4 for middle income countries, and 4.1 for low income countries http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/2.17. Fertility differences were higher in 1990.

Results in both significance and sign are robust to studying instead the difference between childless individuals and those who having at least one child, or to using a probit.

The results of these tests are not presented here but are available upon request.

Given the nature of the dependent variable, using probits and probit models with continuous endogenous regressors or IVProbit would have been preferred. However, a subsequent problem remains in that the probit estimation provides high estimates when the instrumented variable is discrete and the estimates are close to zero (Wooldridge 2001, Chapt. 15). I use 2SLS results in my analysis that correspond to the best linear approximation. Nevertheless, the analysis holds in both sign and significance when IVProbit estimates are used. Results for the probit estimations are presented in Appendix A. When using probits I calculate marginal effects at the means, both directly and instrumented, so the estimates can be compared with the OLS method. As expected, effects at the means are very high when using probits.

References

Ahmad, N., & Hoffman, A. (2007). A framework for addressing and measuring entrepreneurship. Technical report, OECD, Paris, France. http://www.oecd.org/industry/business-stats/39629644.pdf.

Altonji, J. G., & Dunn, T. A. (2000). An intergenerational model of wages, hours, and earnings. The Journal of Human Resources, 35(2), 221–258. doi:10.2307/146324.

Ardagna, S., & Lusardi, A. (2008). Explaining international differences in entrepreneurship: the role of individual characteristics and regulatory constraints. In Lerner, J., & Schoar, A. (Eds.) International differences in entrepreneurship (pp. 17–62). Chicago, Illinois, USA: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226473109.001.0001. Chap. 1.

Axinn, W. G., Clarkberg, M. E., & Thornton, A. (1994). Family influences on family size preferences. Demography, 31(1), 65–79. doi:10.2307/2061908.

Blanchflower, D. G. (2000). Self-employment in OECD countries. Labour Economics, 7(5), 471–505. doi:10.1016/S0927-5371(00)00011-7.

Boden, R. J. (1996). Gender and self-employment selection: an empirical assessment. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 25(6), 671–682. doi:10.1016/S1053-5357(96)90046-3.

Boden, R. J. (1999). Flexible working hours, family responsibilities, and female self-employment. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 58(1), 71–83. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.1999.tb03285.x.

Broussard, N.H., Chami, R., & Hess, G.D. (2015). (Why) do self-employed parents have more children? Review of Economics of the Household, 13(2), 297–321. doi:10.1007/s11150-013-9190-0.

Browning, M. (1992). Children and household economic behavior. Journal of Economic Literature, 30(3), 1434–1475.

Budig, M. J. (2006). Gender, self-employment, and earnings: the interlocking structures of family and professional status. Gender & Society, 20(6), 725–753. doi:10.1177/0891243206293232.

Burton, M. D., Sørensen, J.B., & Dobrev, S.D. (2016). A careers perspective on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 40(2), 237–247. doi:10.1111/etap.12230.

Caliendo, M., Fossen, F., & Kritikos, A. S. (2014). Personality characteristics and the decisions to become and stay self-employed. Small Business Economics, 42(4), 787–814. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9514-8.

Carr, D. (1996). Two paths to self-employment?: women’s and men’s self-employment in the United states, 1980. Work and Occupations, 23(1), 26–53. doi:10.1177/0730888496023001003.

Cetindamar, D., & Gupta, V. K. (2012). What the numbers tell: the impact of human, family and financial capital on women and men’s entry into entrepreneurship in Turkey. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(1-2), 29–51. doi:10.1080/08985626.2012.637348.

Charness, G., & Jackson, M. O. (2009). The role of responsibility in strategic risk-taking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 69(3), 241–247. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2008.10.006.

Chlosta, S., Patzelt, H., Klein, S. B., & Dormann, C. (2012). Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: the moderating effect of personality. Small Business Economics, 38(1), 121–138. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9270-y.

Cramer, J. S., Hartog, J., Jonker, N., & Van Praag, C. M. (2002). Low risk aversion encourages the choice for entrepreneurship: an empirical test of a truism. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 48(1), 29–36. doi:10.1016/S0167-2681(01)00222-0.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2011). Individual risk attitudes: measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3), 522–550. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01015.x.

Drago, R., Wooden, M., & Black, D. (2009). Who wants and gets flexibility? Changing work hours preferences and life events. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 62(3), 394–414. doi:10.1177/001979390906200308.

Dunn, T., & Holtz-Eakin, D. (2000). Financial capital, human capital, and the transition to self-employment: evidence from intergenerational links. Journal of Labor Economics, 18(2), 282–305. doi:10.1086/209959.

Dunning, D., Heath, C., & Suls, J. M. (2004). Flawed self-assessment: implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(3), 69–106. doi:10.1111/j.1529-1006.2004.00018.x.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). Forecasting risk attitudes: an experimental study using actual and forecast gamble choices. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 68(1), 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2008.04.006.

Ekelund, J., Johansson, E., Järvelin, M. R., & Lichtermann, D. (2005). Self-employment and risk aversion - evidence from psychological test data. Labour Economics, 12 (5), 649–659. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2004.02.009.

Guiso, L., & Paiella, M. (2008). Risk aversion, wealth, and background risk. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(6), 1109–1150. doi:10.1162/jeea.2008.6.6.1109.

Hamilton, B. H. (2000). Does entrepreneurship pay? An empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. Journal of Political Economy, 108(3), 604–631. doi:10.1086/262131.

Hout, M., & Rosen, H. S. (2000). Self-employment, family background, and race. The Journal of Human Resources, 35(4), 670–692. doi:10.2307/146367.

Hundley, G. (2006). Family background and the propensity for self-employment. Industrial Relations, 45(3), 377–392. doi:10.1111/j.1468-232X.2006.00429.x.

Hurst, E., & Lusardi, A. (2004). Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Political Economy, 112(2), 319–347. doi:10.1086/381478.

Kahneman, D., & Snell, J. (1992). Predicting a changing taste: do people know what they will like? Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 5(3), 187–200. doi:10.1002/bdm.3960050304.

Kelley, D. J., Ali, A., Brush, C., Corbett, A. C., Lyons, T., Majbouri, M., & Rogoff, E.G. (2013). National entrepreneurial assessment for the United States of America. Technical report, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, London, UK. http://www.gemconsortium.org/docs/download/3375.

Lerner, J., & Schoar, A. (2010). International differences in entrepreneurship. In Lerner, J., & Schoar, A. (Eds.) International differences in entrepreneurship (pp. 1–13). Chicago, Illinois, USA: University of Chicago Press, 10.7208/chicago/9780226473109.001.0001.

Macpherson, D. A. (1988). Self-employment and married women. Economics Letters, 28(3), 281–284. doi:10.1016/0165-1765(88)90132-2.

Mondragón-Vélez, C., & Peña, X. (2010). Business ownership and self-employment in developing economies: the Colombian case. In Lerner, J., & Schoar, A. (Eds.) International differences in entrepreneurship (pp. 89–127). Chicago, Illinois, USA: University of Chicago Press, 10.7208/chicago/9780226473109.003.0004. Chap. 3.

Noseleit, F. (2014). Female self-employment and children. Small Business Economics, 43(3), 549–569. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9570-8.

Pahlke, J., Strasser, S., & Vieider, F. M. (2015). Responsibility effects in decision making under risk. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 51(2), 125–146. doi:10.1007/s11166-015-9223-6.

Parker, S. C. (2004). The economics of self-employment and entrepreneurship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511493430.

Rupasingha, A., & Goetz, S. J. (2013). Self-employment and local economic performance: evidence from US counties*. Papers in Regional Science, 92(1), 141–161. doi:10.1111/j.1435-5957.2011.00396.x.

Schmidt, L. (2008). Risk preferences and the timing of marriage and childbearing. Demography, 45 (2), 439–460. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0005.

Smith, T.W., Marsden, P., Hout, M., & Kim, J. (2013). General social surveys, 1972–2012-r1. Dataset. doi:10.3886/ICPSR34802.v1.

Stock, J. H., Wright, J. H., & Yogo, M. (2002). A survey of weak instruments and weak identification in generalized method of moments. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 20(4), 518–529. doi:10.1198/073500102288618658.

Wen, J.-F., & Gordon, D.V. (2014). An empirical model of tax convexity and self-employment. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(3), 471–482. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00388.

Wolff, E. N., & Gittleman, M. (2014). Inheritances and the distribution of wealth or whatever happened to the great inheritance boom? Journal of Economic Inequality, 12(4), 439–468. doi:10.1007/s10888-013-9261-8.

Wooldridge, J. (2001). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA, USA: The MIT Press.

Zagorsky, J. L. (2013). Do people save or spend their inheritances? Understanding what happens to inherited wealth. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 34(1), 64–76. doi:10.1007/s10834-012-9299-y.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Robert Oxoby, Ana Ferrer, Atsuko Tanaka, Jean-Francois Wen, Curtis Eaton, the editor and two anonymous referees for valuable comments. Generous financial support by the Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarships, provided by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council, is acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Probit results

Appendix B: Instrumented regressions using mother’s self-employment

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caballero, G.A. Responsibility or autonomy: children and the probability of self-employment in the USA. Small Bus Econ 49, 493–512 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9840-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9840-3