Abstract

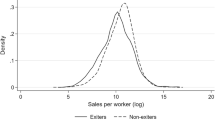

This paper uses a unique dataset from the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys in 47 economies to analyze the conditions under which firms leave heterogeneous markets. Consistent with expectations, we show that firm productivity (and age) are significant determinants of firm exit. Cross-country analysis shows, however, that the relationship between productivity as well as age and exit is mitigated by some country-level factors. In particular, we show either’s effect is substantially weakened in low-income economies, economies with limited openness to international trade, and in economies with cumbersome bankruptcy procedures. To address issues of sample attrition and selection bias presented by survey-based estimates, corrections are applied using information when a firm’s operating status is uncertain. The expected negative relationship between firm labor productivity and the likelihood of exit is robust to these corrections, as is the negative relationship between firm exit and age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

φ it could also denote the current resale value of the business.

Broadly, these are considered factors of production. While fundamental, a firm’s capital k it presents several measurement complications, including that there is no reliable way to measure it for service firms in our dataset. As a result, we do not include capital directly in our firm-level co-variates, but consider it as proxied by firm size, though size may also capture other characteristics.

It is important to note that distortions may also factor into firm productivity itself, particularly depending on how the concept is defined. For example Foster et al. (2008) lay out the difference between quantity-based and revenue-based productivity measures, noting that the latter are more often available but are unable to separate out distortions through such channels as market power or asymmetric information, each of which can affect the price and revenue function of a firm. Here, we note that the revenue function itself takes these into account and so we do not address revenue and quantity-based productivity distinctions.

There is limited evidence on the link between firm exit and entry barrier policies, the few studies available indicating that these polices do not affect exits (Box 2008).

Further, access to foreign markets enables firms to diversify sales and reduce exit risks arising from negative shocks to the domestic economy (Wagner and Gelübcke 2012; Bernard et al. 2002).

Alternatively, several studies code firm exit as a firm falling below a certain threshold of (usually) employees.

While issues of panel attrition bias have been thoroughly analyzed in numerous household (See Fitzgerald et al. 1998; Thomas et al. 2001; Alderman et al. 2000; Maluccio 2004; Khandker 2005), we have not encountered a thorough analysis of these effects in enterprise or business surveys, particularly in developing economies.

To avoid further cluttering notation we omit country-level sub-scripts.

This also includes firms that have exited the market by moving abroad or are no longer formally registered.

We note that a third naive measure of exit is to consider Group 2 as exiting. For robustness, we ran regressions testing this and find no substantive differences; results are not reported here but are available on request.

They use the Cox proportional hazard semi-parametric method to estimate firm duration or survival. While they find this to be preferable, such methods that are not generally dependent on observables require a full multi-period panel structure, which our data lacks.

Rated by the interviewer.

The initial round for Venezuela (2006) utilized a limited questionnaire and omits certain key covariates. As a result, we remove Venezuela for all analysis (n = 500) so as not to bias our results by the inclusion or exclusion of an entire survey round as new variables are introduced. Annex Table 1 provides the list of countries and survey years included in the analysis.

The annualized exit rate is computed using compounded growth formula.

As we are concerned with the average difference between the groups of exiters (attritors) and survivors within a country, the reported mean differences are the resulting coefficient(s) from an EXIT (ATTRITOR) dummy in the regression: Y = α + β 1 EXIT it + β ' COUNTRY' it + μ it where Y represents the descriptive variable of interest and the vector COUNTRY’ is a series of country fixed effects. This avoids pooling problems across disparate countries at different income levels. In the regression specifications below this is addressed by the use of country-level fixed effects and market-level co-variates.

For more information, the ES website includes a note on sampling methodology, here: http://www.enterprisesurveys.org/~/media/FPDKM/EnterpriseSurveys/Documents/Methodology/Sampling_Note.pdf

Maluccio (2004)

Maluccio (2004)

Using the svy: prefix, Stata calculates an adjusted Wald test.

For this reason and in the interest of space, we do not present further Heckman selection models here. All were run and are available upon request.

This finding, though, has not been universal: Söderbom et al. (2006), for instance, find no or little relationship between firm age and exit.

Bernard and Jensen (2007), for instance, find no significant evidence of a size effect on firm survival.

That productive firms select to exporting has been widely documented. (see for instance, Haidar (2012))

References

Agarwal, R., & Gort, M. (2002). Firm and product life cycles and firm survival. American Economic Review, 92(2), 184–190. doi:10.1257/000282802320189221.

Aldrich, H. E., & Auster, E. (1986). Even dwarfs started small: liabilities of size and age and their strategic implications. Research in Organizational Behavior, 8, 165–198.

Baily, M. N., Hulten, C. and Campbell, D. 1992“Productivity Dynamics in Manufacturing Establishments,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: Microeconomics, 187–249.

Baldwin, J., & Yan, B. (2011). The death of Canadian manufacturing plants: heterogeneous responses to changes in tariffs and real exchange rates. Review of World Economics, 147(1), 131–167. doi:10.1007/s10290-010-0079-1.

Bartelsman, E., Haltiwanger, J., and Scarpetta, S. (2004) “Microeconomic Evidence of Creative Destruction in Industrial and Developing Countries.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 3464. doi:10.1596/1813–9450-3464

Bernard, A. and Sjöholm, F. (2003). “Foreign Owners and Plant Survival”. NBER Working Papers 10039. doi:10.3386/w10039

Bernard, A., Eaton, J., Jensen, B., & Kortum, S. (2002). Plants and productivity in international trade. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1268–1290. doi:10.1257/000282803769206296.

Bloom, N, Sadun, R, and Van Reenen, J. (2012) “Management as a Technology?” mimeo, Resource document, http://web.stanford.edu/~nbloom/MAT.pdf

Box, M. (2008). The death of firms: exploring the effects of environment and birth cohort on firm survival in Sweden. Small Business Economics, 31(4), 379–393. doi:10.1007/s11187-007-9061-2.

Cable, J. and Scwalbach, J. (1991). “International Comparisons of Entry and Exit”. In P.A. Geroski and J. Schwallbach (Eds.), Entry and Market Contestability: An International Comparison (pp 257–81). Oxford, U.K. and Cambridge, MA.: Blackwell Publishing.

Cader, H. A., & Leatherman, J. C. (2011). Small business survival and sample selection bias. Small Business Economics, 37(2), 155–165. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9240-4.

Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2012). Strong Evidence for Gender Differences in Risk Taking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 83(1), 50–58. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2011.06.007.

Couwenberg, O. (2001). Survival rates in bankruptcy systems: overlooking the evidence. European Journal of Law and Economics, 12(3), 253–273. doi:10.1023/A:1012821909622.

Croson, R., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2), 448–474. doi:10.1257/jel.47.2.448.

Dewaelheyns, N., & Van Hulle, C. (2008). Legal reform and aggregate small and micro business bankruptcy rates: evidence from the 1997 Belgian bankruptcy code. Small Business Economics, 31(4), 409–424. doi:10.1007/s11187-007-9060-3.

Disney, R., Haskel, J., & Heden, Y. (2003). Entry, exit and establishment survival in UK manufacturing. Journal of Industrial Economics, 51(1), 91–112. doi:10.1111/1467-6451.00193.

Dunne, T., Roberts, M., & Samuelson, L. (1989). The growth and failure of U.S. manufacturing plants. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4), 671–698. doi:10.2307/2937862.

Ericson, R., & Pakes, J. (1995). Markov-perfect industry dynamics: a framework for empirical work. The Review of Economic Studies, 62(1), 53–82. doi:10.2307/2297841.

Eslava, M. and Haltiwanger, J. (2014). “Young Businesses, Entrepreneurship, and the Dynamics of Employment and Output in Colombia’s Manufacturing Industry”, mimeo, http://www.banrep.gov.co/sites/default/files/eventos/archivos/sem_11_cali.pdf

Faccio, M., Marchica, M. T., & Mura, R. (2016). CEO gender and corporate risk-taking. Journal of Corporate Finance. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.02.008.

Fackler, D., Schnabel, C., & Wagner, J. (2013). Establishment exits in Germany: the role of size and age. Small Business Economics, 41(3), 683–700. doi:10.1007/s11187-012-9450-z.

Fariñas, J., & Ruano, S. (2005). Firm productivity, heterogeneity, sunk costs, and market selection. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 23(7–8), 505–534. doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2005.02.002.

Fitzgerald, J., Gottschalk, P., & Moffitt, R. (1998). An analysis of sample attrition in panel data: the Michigan panel study of income dynamics. The Journal of Human Resources, 33(2), 251–299. doi:10.3386/t0220.

Foster, L., Haltiwanger, J. and Krizan, C. J. (2001). Aggregate Productivity Growth Lessons from Microeconomic Evidence, in (editors) C. Hulten, E. Dean and M. Harper, New Developments in Productivity Analysis (2001), (pp. 303–372). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.3386/w6803

Foster, L., Haltiwanger, J., & Syverson, C. (2008). Reallocation, firm turnover, and efficiency: selection on productivity or profitability? American Economic Review, 98(1), 394–425. doi:10.1257/aer.98.1.394.

Frazer, G. (2005). Which firms die? A look at manufacturing firm exit in Ghana. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 53(3), 585–617. doi:10.1086/427246.

Gelübcke, J., & Wagner, J. (2012). Foreign ownership and firm survival: first evidence for enterprises in Germany. Economie Internationale, 132, 117–139. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.843.

Greene, W. (2010). Testing hypotheses about interaction terms in nonlinear models. Economics Letters, 107(2), 291–296. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2010.02.014.

Haidar, J. (2012). Trade and productivity: self-selection or learning-by-exporting in India. Economic Modelling, 29(2012), 1766–1773. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2012.05.005.

Hallward-Driemeier, M., & Rijkers, B. (2013). Do crises catalyze creative destruction? Firm-level evidence from Indonesia. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(5), 1788–1810. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-5869.

Harhoff, D., Stahl, K., & Woywode, M. (1998). Legal form, growth and exit of west German firms. Journal of Industrial Economics, 46, 453–488. doi:10.1111/1467-6451.00083.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47, 153–161. doi:10.2307/1912352.

Hopenhayn, H. (1992). Entry, exit, and firm dynamics in long run equilibrium. Econometrica, 60(5), 1127–1150. doi:10.2307/2951541.

Hopenhayn, H., & Rogerson, R. (1993). Job turnover and policy evaluation: a general equilibrium analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 101(5), 915–938. doi:10.1086/261909.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50(3), 649–670. doi:10.2307/1912606.

Keil, T., & Pe’era, A. (2012). Are all startups affected similarly by clusters? Agglomeration, competition, firm heterogeneity, and survival. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(3), 354–372. doi:10.1007/s11747-012-0316-3.

Khandker, S. R. (2005). Microfinance and poverty: evidence using panel data from Bangladesh. The World Bank Economic Review, 19(2), 263–286. doi:10.1093/wber/lhi008.

King, R., & Levine, R. (1993). Finance, entrepreneurship, and growth: theory and evidence. Journal of Monetary Economics, 32(3), 513–542. doi:10.12691/ijefm-2-2-1.

Klapper, L. and Richmond, C. (2011). “Patterns of Business Creation, Survival and Growth Evidence from Africa”, Policy Research Working Paper 5828. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-5828

Klapper, L., Laeven, L., & Rajan, R. (2006). Entry regulation as a barrier to entrepreneurship. Journal of Financial Economics, 82(3), 591–629. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.09.006.

Levine, R. (2005). Finance and Growth: Theory and Evidence. In P. Aghion and S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth, (pp. 865–934). Netherlands: Elsevier Science.

Liu, L. (1993). Entry-exit, learning and productivity change: evidence from Chile. Journal of Development Economics, 42, 217–242. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(93)90019-J.

Liu, L. and Tybout, J. (1996). Productivity Growth in Colombia and Chile: Panel-based Evidence on the Role of Entry, Exit, and Learning. In M. Roberts and J. Tybout (Eds.), (pp. )

Maluccio, J. (2004). Using quality of interview information to assess nonrandom attrition bias in developing-country panel data. Review of Development Economics, 8(1), 91–109. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9361.2004.00222.x.

Melitz, M. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725. doi:10.1111/1468-0262.00467.

Mengistae, T. (2006) Competition and entrepreneurs’ human capital in small business longevity and growth. Journal of Development Studies, Taylor & Francis Journals, 42(5), 812–836. doi:10.1080/00220380600742050.

Olley, S., & Pakes, A. (1996). The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica, 64(6), 1263–1297. doi:10.2307/2171831

Pakes, A., & Ericson, R. (1998). Empirical implications of alternative models of firm dynamics. Journal of Economic Theory, 79(1), 1–46. doi:10.1006/jeth.1997.2358.

Pavcnik, N. (2002). Trade liberalization, exit, and productivity improvements: evidence from Chilean plants. Review of Economic Studies, 69(1), 245–276. doi:10.1111/1467-937X.00205.

Perez, S. E., Llopis, A. S., & Llopis, J. A. (2004). The determinants of survival of Spanish manufacturing firms. Review of Industrial Organization, 25(3), 251–273. doi:10.1007/s11151-004-1972-3.

Shiferaw, A. (2009). Survival of private sector manufacturing establishments in Africa: the role of productivity and ownership. World Development, 37(3), 572–584. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.004.

Soderbom, M., Teal, F., & Harding, A. (2006). The determinants of survival among African manufacturing firms. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54(3), 533–555. doi:10.1086/500030.

Thomas, D., Frankenberg, E., & Smith, J. P. (2001). Lost but not forgotten: attrition and follow-up in the Indonesia family life survey. Journal of Human Resources, 36(3), 556–592. doi:10.2307/3069630.

Thorburn, K. (2000). Bankruptcy auctions: costs, debt recovery, and firm survival. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(3), 337–368. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(00)00075-1.

Young, M., Ahstrom, D., & Bruton, G. (2004). The globalization of corporate governance in East Asia: the ‘transnational’ solution. Management and International Review, 2, 31–50. doi:10.1007/978-3-322-90997-8_3.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to two anonymous referees and the journal editors for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aga, G., Francis, D. As the market churns: productivity and firm exit in developing countries. Small Bus Econ 49, 379–403 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9817-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9817-7