Abstract

This paper examines how the distribution of skills, organizational diseconomies of size, and the introduction of a minimum wage affect the total output of the economy and the relative size and average per capita income of employees, solo self-employed, and employers, in a market equilibrium from occupational choices of individuals with different skills. The model explains the heterogeneity observed among occupational groups beyond employers and employees, and predicts differences in the sing of the association between entrepreneurs’ rates and economic development depending on the entrepreneurs’ type. The introduction of a minimum wage leads to involuntary solo self-employed, more skilled voluntary solo self-employed, and fewer employers. A minimum wage lowers total output and has income redistribution effects: income per capita decreases in the individuals in the two extremes of the skills’ distribution and increases in the middle class.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Precisely, who is an entrepreneur is determined according to behavioral and occupational criteria (Sternberg and Wennekers 2005). The former considers entrepreneurs as those individuals who innovate (Acs and Audretsch 1988; Audretsch and Keilbach 2004; Wong et al. 2005; Minniti and Lévesque 2010) and/or start a business (Carree et al. 2002; Hurst and Lusardi 2004; Reynolds et al. 2005; Cagetti and De Nardi 2006; Acs et al. 2008). From an occupational point of view, entrepreneurs are self-employed people who own and/or manage a business (Evans and Jovanovic 1989; Evans and Leighton 1989; Blanchflower and Oswald 1998). This paper only considers heterogeneity among entrepreneurs from occupational choices.

The contribution of entrepreneurship to economic development has attracted the interest of national governments and supranational organizations such as the World Bank, OECD, and the European Commission; academics (Parker 2004; Audretsch et al. 2006; Baumol 2010; to name a few of the book reviews); and ambitious data collection projects such as GEM (Reynolds et al. 2005) and COMPENDIA (van Stel 2005).

We omit other friction sources such as liquidity or financial constraints (Evans and Jovanovic 1989; Guiso et al. 2004, Hurst and Lusardi 2004), product market regulations (Klapper et al. 2006), personal income taxes (Blau 1987; Gentry and Hubbard 2000; Parker and Robson 2004), and labor market regulations (Ardagna and Lusardi 2010).

The complete list of occupational groups includes many of the entrepreneurial types reported in Wennekers et al (2010). The distinction between the voluntary and involuntary self-employed resembles the GEM distinction between opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs, although this paper considers the entrepreneurial action as an occupational choice and not a decision to start a particular business. Additionally, the occupational groups in this paper are part of a market equilibrium solution in which the number of entrepreneurs is determined together with the number of employees and unemployed.

Skills are not directly observable but are reasonably correlated with human capital variables such as the education, experience, and family background of the working population, which differ among workers in different occupations (Evans and Leighton 1989; Evans and Jovanovic 1989; Dawson et al. 2014). Other variables suggested as determinants of occupational choices—e.g., preferences for independent work, risk aversion, and personal wealth—have mixed empirical support (Landier and Thesmar 2009).

In Lucas’ (1978) original paper, individuals differ only in entrepreneurial skills and had the same operational skills. Jovanovic (1994) assumed that individuals were endowed with two skills, operational and managerial. Garicano (2000) and Garicano and Rossi-Hansberg (2006) modeled production in cognitive organizational hierarchies where managers and workers specialized in problem-solving of different complexities; there was optimal matching between entrepreneurs and employees in the market equilibrium. Roessler and Koellinger (2012) also modeled the market equilibrium with occupational choices where employees could be complementary rather than substitutive (as in this paper); there was an optimal matching between entrepreneurs and employees.

Models on organization point to the cost of loss of control (Williamson 1967; Calvo and Wellisz 1978), agency costs (Holmstrom 1979; Rosen 1982), and cost of information processing and communication (Garicano 2000) as determinants of the centralization and decentralization of decisions in hierarchies.

Blau (1987) explained the observed differences in the self-employed rates in US industries as the consequences of differences in production technologies of the solo self-employed versus business owners. Salas-Fumás and Sanchez-Asin (2013a) found that, based on Spanish data, industry differences in self-employment rates were more pronounced for solo self-employed than for employers.

We first computed the equilibrium value of e 2 from the first expression (which only depends on the exogenous parameters m, k, β, and e M). Next, we computed the equilibrium values of e 1 and w * from the second and third expressions.

The range of reasonable values of parameter β will have to be determined empirically. From the condition that determines the profit-maximizing value of operational skills E, the compensation to employees supply the total skills E is equal to a proportion 1 − β of the total output. National Accounts data from different countries show that the compensation to salaried employees represents about 60 % of the total value added. The other 40 % includes the costs of the capital input service and the entrepreneurial rents. In our model with inputs operational and entrepreneurial skills and no capital services, values of parameter β above 0.4 would be quite unrealistic. The signs of the comparative static analysis for changes in β in Table 1 are obtained for values of β between 0 and 0.4.

We created a table similar to Table 1 for an economy with only two occupational choices (no solo self-employment) and found that the signs of the comparative static exercise changed with two or three occupational choices. This is relevant because the occupational choice models for policy analysis (Braguinsky et al. 2011; Garicano et al. 2013) considered only two choices, whereas a realistic case would have three choices.

For m = 3, i.e., a minimum wage equal to one-third of the average equilibrium wage, the number of individuals working as employees under no minimum wage who become unemployed or involuntary solo self-employed is reduced to 8.4 %, but their average income as self-employed is lower than when m = 2 because their average skills are also lower.

Under these conditions, Eq. (34) implies that \( {{e^{*} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{e^{*} } {e_{M} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {e_{M} }} = 1 \), which supports this result.

With β = 1, denoting extreme organizational size diseconomies and no market frictions, Eq. (14) converges to (13) with k = 1. Each individual works as a solo self-employed, and the total output produced is the sum of the individual outputs. With respect to the distribution of skills in the base scenario, this total output is 3,700, 33 % lower than the maximum output with β = 0.

See also Kuznets (1966), Yamada (1996), and Gollin (2008). Other research postulates a U- or L-shaped relationship between self-employment rates and per capita income of different countries, so the negative association between the two variables is only significant to certain level of per capita income, beyond which it would be flat or slightly positive (see Carree, et al. 2002, 2007; Wennekers et al. 2010 for a review). Our results could explain this empirical regularity as due to the fact that the self-employed in low-income countries are primarily involuntary self-employed, while in high-income countries they belong to the group of voluntary solo self-employed and employers.

References

Acs, Z., & Audretsch, D. (1988). Innovation in small and large firms: An empirical analysis. American Economic Review, 78(4), 678–690.

Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Klapper, L. F. (2008). What does “entrepreneurship” data really show? Small Business Economics, 31(3), 265–281.

Ardagna, S., & Lusardi, A. (2010). Explaining differences in entrepreneurship. The role of characteristics and regulatory constraints. In J. Lerner & M. Schoar (Eds.), International differences in entrepreneurship (pp. 63–88). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2004). Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Regional Studies, 38(8), 949–959.

Audretsch, D. B., Keilbach, M., & Lehmann, E. (2006). Entrepreneurship and economic growth. New York: Oxford University Press.

Banerjee, A. V., & Newman, A. F. (1993). Occupational choice and the process of development. Journal of Political Economy, 101(2), 274–298.

Baumol, W. (2010). The micro-theory of innovative entrepreneurship. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Betcherman, G. (2014). Labor market regulations: What do we know about their impacts in developing countries? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6819. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2417517.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (1998). What makes an entrepreneur? Journal of Labor Economics, 16(1), 26–60.

Blau, D. M. (1987). A time series analysis of self-employment in the US. Journal of Political Economy, 95(3), 445–467.

Bloom, N., Garicano, L., Sadun, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2009). The distinct effects of information technology and communication technology on firm organization. National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER Working Paper No. 14975. http://www.nber.org/papers/w14975.pdf?new_window=1.

Bloom, N., Sadun, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2012). The organization of firms across countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(4), 1663–1705.

Bögenhold, D., & Fachinger W. (2007). Renaissance of Entrepreneurship? Some remarks and empirical evidence for Germany. Zentrum für Sozialpolitik Universität Bremen. ZeS-Arbeitspapier Nr. 2/2007. http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/3186/.

Braguinsky, S., Branstetter, L., & Regateiro, A. (2011). The incredible shrinking of Portuguese firms. National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER Working Paper No. 17265.

Burstein, A. T., & Monge-Naranjo, A. (2009). Foreign know-how, firm control, and the income of developing countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(1), 149–195.

Cagetti, M., & De Nardi, M. (2006). Entrepreneurship, frictions, and wealth. Journal of Political Economy, 114(5), 835–870.

Calvo, G. A., & Wellisz, S. (1978). Supervision, loss of control and the optimal size of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 86(5), 943–952.

Carree, M., van Stel, A., Thurik, R., & Wennekers, S. (2002). Economic development and business ownership: An analysis using data of 23 OECD countries in the period 1976–1996. Small Business Economics, 19(3), 271–290.

Carree, M., van Stel, A., Thurik, R., & Wennekers, S. (2007). The relationship between economic development and business ownership revisited. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(3), 281–291.

Dawson, C., Henley, A., & Leteille, P. (2014). Individual motives for choosing self-employment in the UK: Does region matter? Regional Studies, 48(5), 804–822.

Eeckhout, J., & Jovanovic, B. (2012). Occupational choice and development. Journal of Economic Theory, 147(2), 657–683.

Evans, D., & Jovanovic, B. (1989). An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), 808–827.

Evans, D., & Leighton, L. S. (1989). Some empirical aspects of entrepreneurship. American Economic Review, 79(3), 519–535.

Fritsch, M., Kriticos, A., & Rusakova, A. (2012). Who starts a business and who is self-employed in Germany. Jena Economic Research Papers # 001-2012, Friedrich Schiller University and Max Planck Institute of Economics Jena. http://www.uiw.uni-jena.de/images/stories/04research/publications2012/2012-001.pdf.

Garicano, L. (2000). Hierarchies and the organization of knowledge in production. Journal of Political Economy, 108(5), 874–904.

Garicano, L., LeLarge, C., & Van Reenen, J. (2013). Firm size distortions and the productivity distribution: Evidence from France. National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER Working Paper No. 18841.

Garicano, L., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2006). Organization and inequality in a knowledge economy. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(4), 1383–1435.

Gennaioli, N., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2013). Human capital and regional development. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1), 105–164.

Gentry, W., & Hubbard, R. (2000). Tax policy and entrepreneurial entry. American Economic Review, 90(2), 283–287.

Gindling, T. H., & Newhouse, D. (2012). Self-employment in the developing world. World Bank Policy Research WP 6201. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-6201.

Gollin, D. (2008). Nobody’s business but my own: Self-employment and small enterprise in economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 55(2), 219–233.

Guiso, L., Sapieza, P., & Zingales, L. (2004). Does local financial development matter? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(3), 929–969.

Henrekson, M., Sanandaji, T., 2014. Small Business Activity does not Measure Entrepreneurship. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science of the USA. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307204111.

Holmstrom, B. (1979). Moral hazard and observability. Bell Journal of Economics, 10(1), 74–91.

Hurst, E., & Lusardi, A. (2004). Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Political Economy, 112(2), 319–347.

ILO. (2013). World of Work Report 2013. Repairing the economic and social fabric. International Labour Organization. International Institute for Labour Studies. Geneva, Switzerland.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of Industry. Econometrica, 50(3), 649–670.

Jovanovic, B. (1994). Firm formation with heterogeneous management and labor skills. Small Business Economics, 6(4), 185–191.

Kihlstrom, R., & Laffont, J. (1979). A general equilibrium entrepreneurial theory of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 87(4), 719–748.

Klapper, L., Laeven, L., & Rajan, R. G. (2006). Entry regulation as a barrier to entrepreneurship. Journal of Financial Economics, 82(3), 591–629.

Kuznets, S. (1966). Modern economic growth. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). Trust in large organizations. American Economic Review, 87(2), 333–338.

Landier, A., & Thesmar, D. (2009). Financial contracting with optimistic entrepreneurs. Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 117–150.

Lerner, J., & Schoar, A. (Eds.). (2010). International differences in entrepreneurship. Chicago, IL: National Bureau of Economic Research. University of Chicago Press.

Lucas, R. (1978). On the size distribution of firms. The Bell Journal of Economics, 9(2), 508–523.

Malchow-Møller, N., Markusen, J. R., & Skaksen, J. R. (2010). Labour market institutions, learning and self-employment. Small Business Economics, 35(1), 35–52.

Minniti, M., & Lévesque, M. (2010). Entrepreneurial types and economic growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(3), 305–314.

Neumark, D., & Wascher, W. L. (2007). Minimum wages and employment. Foundations and Trends in Microeconomics, 3(1–2), 1–182. doi:10.1561/0700000015.

Parker, S. C. (2004). The economics of self-employment and entrepreneurship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parker, S. C., & Robson, M. (2004). Explaining international variations in self-employment: Evidence from OECD countries. Southern Economic Journal, 71(2), 287–301.

Poschke, M. (2008). Who becomes an entrepreneur? Labor market prospects and occupational choice. IZA Discussion Paper No. 3816. Version July 2012. http://markus-poschke.research.mcgill.ca/papers/mposchke_occchoice.pdf.

Reynolds, P. D., Bosma, N., Autio, E., Hunt, S., Servais, I., Lopez-Garcia, P., et al. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 205–231.

Roessler, Ch., & Koellinger, Ph. (2012). Entrepreneurship and organization design. European Economic Review, 54(5), 888–902.

Rosen, S. (1981). The economics of superstars. American Economic Review, 71(5), 845–858.

Rosen, S. (1982). Authority, control, and the distribution of earnings. The Bell Journal of Economics, 13(2), 311–323.

Salas Fumás, V., & Sanchez-Asin, J. J. (2013). Information and trust in hierarchies. Decision Support Systems, 55(4), 988–999.

Salas-Fumás, V., & Sanchez-Asin, J. J. (2013a). The management function of entrepreneurs and countries’ productivity growth. Applied Economics, 45(17), 2349–2360.

Salas-Fumás, V., & Sanchez-Asin, J. J. (2013b). Entrepreneurial dynamics of the self-employed and of firms: a comparison of determinants using Spanish data. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 9(3), 417–446.

Schmitt, J. (2013). Why does the minimum wage have no discernible effect on employment? CEPR. Center for Economic and Policy Research. Report February 2013. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage-2013-02.pdf.

Stenholm, P., Acs, Z. J., & Webker, R. (2013). Exploring country-level institutional arrangements on the rate and type of entrepreneurial activity. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(1), 176–193.

Sternberg, R., & Wennekers, S. (2005). Determinants and effects of new business creation using global entrepreneurship monitor data. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 193–203.

van Stel, A. (2005). COMPENDIA: Harmonizing business ownership data across countries and over time (1972–2002). International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1(1), 105–123.

Wennekers, S., van Stel, A., Carree, M., & Thurik, R. (2010). The relationship between entrepreneurship and economic development: is it U-shaped? Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 6(3), 167–231.

Williamson, O. (1967). Hierarchical control and optimal firm’s size. Journal of Political Economy, 75(2), 123–138.

Wong, P. K., Ho, Y. P., & Autio, E. (2005). Entrepreneurship, innovation and economic growth: evidence from GEM data. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 335–350.

Yamada, G. (1996). Urban informal employment and self-employment in developing countries: Theory and evidence. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 44(2), 289–314.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the project ECO2009-13158 MICINN-PLAN NACIONAL I+D, and CREVALOR-DGA-FSE. The authors thank the valuable comments and suggestions from the two anonymous reviewers and from the Journal Editor on previous versions of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: The market equilibrium solution for the power production function and the uniform distribution of skills

This appendix shows the calculations used to obtain the market equilibrium solution for the occupational choice problem formulated in Sect. 3. We recall that the skills of the individuals are uniformly distributed in the interval [e m , e M ], and the production function of an employer with skills e combined with E units of operational skills from salaried employees is given by

The profit-maximizing demand for skills from (3) and (19) is equal to

Substituting back into the profit function, we obtain

The market equilibrium conditions with only two occupational choices, employers and employees, (Eqs. (4) and (5) in the main text) are

Based on the Eq. (21), we can solve for skill price (as a function of e *):

Substituting into Eq. (22), we obtain the equilibrium level of skills that makes the choice between being an employee or an entrepreneur–manager indifferent (e *):

There are \( \frac{{e_{\text{M}} - e^{*} }}{{e_{\text{M}} - e_{\text{m}} }} \) employers and \( \frac{{e^{*} - e_{0} }}{{e_{\text{M}} - e_{\text{m}} }} \) employees in the equilibrium. The remainder \( \frac{{e_{0} - e_{\text{m}} }}{{e_{\text{M}} - e_{\text{m}} }} \) are unemployed (when e 0 > e m or e * > (2 m − 1)e m , from (15)). The equilibrium average of employees per employer, as a span of control (ASC *), is equal to

The total produced output is given by \( Q^{*} = \mathop \smallint \nolimits_{{e^{*} }}^{{e_{M} }} e^{1 + \beta } \left( {E^{*} \left( e \right)} \right)^{1 - \beta } {\text{d}}H(e) \):

1.1 Voluntary and involuntary solo self-employment

1.1.1 Voluntary solo self-employment

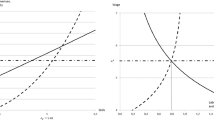

The voluntary solo self-employed are individuals who have sufficient skills to work as salaried employees but choose to be self-employed without employees. In the two-choice economy of employers and employees, an individual with skills e working as an employee makes an income of w(e *)e where w(e *) is the equilibrium price per unit of skill (23). An equilibrium of employers and employees is not sustainable if R(e), the income from solo self-employment, is higher than the salaried-employee income w(e *)e for some e ≤ e *. Because salary is increasing and linear in e and income from self-employment is increasing and convex in e, a necessary condition for an equilibrium with voluntary solo self-employed is that R(e) intersects w(e *)e from below at some value of e < e *. Conversely, the maximum value of k for which the equilibrium with employers and employees is sustainable is k c for which the revenue of the highest skilled employee as self-employed, R(e *), is equal to the salary as employee, w(e *) e *: R(e *) = w(e *)e *, or θβ β(1 − β)1−β e *2 = θk c e *2. Therefore,

If k < k c then for e < e *, income as a solo self-employed is always lower than income as a salaried employee, whereas if k > k c , then at e *, income as a self-employed is higher, and therefore, the intersection between R(e) for this value of k and w(e *)e occurs at a value of e < e *.

1.1.2 Involuntary self-employment

The indifference condition for people with skills lower than e 0 working as (involuntary) self-employed or staying unemployed is R(e s ) = θke 2 s = U. Solving this equation derives the following equation

1.1.3 Market equilibrium solution

The equations that determine the critical levels of skills e 2 and e 1 as a function of the price per unit of skill w are

Solving Eqs. (29) and (30), we obtain

and

The equilibrium value e 2 and the equilibrium price per unit of skill obtained from this value were dependent on the condition that the supply of employee skills equals the demand of skills by employers

Taking into account (31) and (32), the solution to this equation is

The solution e 2 in (33) is substituted into (32) to obtain the equilibrium value of e 1; we can then obtain \( e_{0} = {\text{Max}}\left( {\frac{{e_{1} }}{2m - 1},e_{m} } \right) \). There are \( \frac{{e_{M} - e_{2} }}{{e_{M} - e_{m} }} \) persons working as employers–managers in the equilibrium; \( \frac{{e_{2} - e_{1} }}{{e_{M} - e_{m} }} + \frac{{e_{0} - e_{s} }}{{e_{M} - e_{m} }} \) own-account self-employed and \( \frac{{e_{1} - e_{0} }}{{e_{M} - e_{m} }} \) salaried employees. The number of persons remaining out of work in the economy is \( \frac{{e_{s} - e_{m} }}{{e_{M} - e_{m} }} \). The average span of control is \( \frac{{e_{1} - e_{0} }}{{e_{M} - e_{2} }} = \frac{{e_{1} }}{{e_{M} - e_{2} }}\frac{2(m - 1)}{2m - 1} \).

The total produced output in the equilibrium with three occupational choices is

In substituting the values of the demand for skills E *(w, e *), we obtain, after certain arrangements, the following solution

Appendix 2: Comparative static analysis in Table 1

We will now outline the proof of the comparative static analysis in Table 1. In all cases, the comparative static results correspond to the case when e 1 > (2 m − 1)e m and e s = e m ; the reservation income U is arbitrarily set equal to zero.

1.1 Number of employers

The number of employers in the equilibrium is equal to

where (e 2/e M ) is given by (33).

1.1.1 Changes in the distribution of skills

We compare the equilibrium value in (35) for the original distribution of skills [e m , e M ] with the equilibrium value under the new distribution [e m + d, e M + d], where d is a positive constant for the mean increasing case and with an equilibrium value under the distribution [e m − d, e M + d] for the variance increase case.

Because (e 2/e M ) is independent of the skills distribution parameters in Eq. (34), all of the effects from the changes in the skills distribution parameters in the equilibrium number of employers are explained by the sign of the differences between the ratio \( \frac{{e_{m} }}{{e_{M} }} \) and the ratios \( \frac{{e_{m} + d}}{{e_{M} + d}} \) and \( \frac{{e_{m} - d}}{{e_{M} + d}} \). The expression \( \frac{{e_{m} + d}}{{e_{M} + d}} \) is higher than \( \frac{{e_{\text{m}} }}{{e_{\text{M}} }} \), whereas the ratio of \( \frac{{e_{m} - d}}{{e_{M} + d}} \) is lower. Therefore, a higher mean with an equal variance in skills distribution increases the number of employers in the equilibrium. A higher variance of the skills distribution with an equal mean reduces the equilibrium number of employers–managers.

1.1.2 Organizational size diseconomies

The equilibrium number of employers in (35) depends on the organizational diseconomies parameter β through the term (e 2/e M ) in (33). The sign of the derivative of (e 2/e M ) with respect to β is undetermined, so the change in the number of employers resulting from changes in the organizational size diseconomies parameter can be either positive or negative. As indicated in the text, the sign shown in Table 1 near the question mark is obtained from the simulations of the market equilibrium for a long list of combinations of values of the model parameters. The simulations indicate that higher values of β are expected to be associated with a higher number of employers.

1.1.3 Productivity parameter k and minimum wage

Based on (33), (e 2/e M ) increases with k and decreases with m. Therefore, the equilibrium number of employers decreases when the comparative disadvantage from the lack of specialization of the own-account self-employed is lower (a higher k). Higher values of m imply a lower endogenous minimum wage, which creates a higher number of employer–managers in the equilibrium.

1.2 Voluntary solo self-employed

Taking into account (32), the number of voluntary solo self-employed in the equilibrium is equal to

1.2.1 Distribution of skills

Because (e 2/e M ) and k are independent of the extreme values of the uniform distribution, the effective sign from the changes in the mean and variance of the distribution of skills on the equilibrium number of voluntary solo self-employed is the same as for the aforementioned employer–managers.

1.2.2 Organizational size diseconomies

The indeterminacy in the sign of the changes in (e 2/e M ) to the changes in β implies that the sign of the changes in the number of voluntary solo self-employed from the changes in the organizational size diseconomies is ambiguous. The simulations suggest a positive effect of β on the number of voluntary solo self-employed.

1.2.3 Productivity parameter k and minimum wage

Based on (33), (e 2/e M ) increases with k and decreases with m. Accounting these results, the equilibrium number of voluntary solo self-employed in (36) increases when the comparative disadvantage from the lack of specialization in solo self-employed is lower (higher k), and it decreases as the minimum wage becomes lower (higher m).

1.3 Involuntary solo self-employed

The equilibrium number of involuntary solo self-employed is given by the following (remembering that e s = e m ):

All the terms in (37) appear in the equilibrium values of the aforementioned employers and voluntary solo self-employed. Therefore, we already know the sign of the changes in these terms from the changes in the model parameters.

1.3.1 Distribution of skills

We compare the value of (37) with the respective value for the new distribution of skills with higher mean and equal variance [e m + d, e M + d] for d positive. It is straightforward that (37) increases with d positive, so the number of involuntary solo self-employed decreases as the average skills increase (for a given variance). We then repeat the exercise with the new distribution with equal mean and higher variance [e m − d, e M + d]. Now, the comparison of the respective values of (37) for d equal and greater than zero provides the opposite results: the number of involuntary solo self-employed increases with the dispersion of the distribution of skills for the equal mean.

1.3.2 Organizational size diseconomies

The indeterminacy in the sign of the changes in (e 2/e M ) to the changes in β implies that the sign of the changes in the number of voluntary solo self-employed from the changes in the organizational diseconomies is ambiguous. However, the numerical analysis shows that the number of involuntary solo self-employed will be lower in economies with higher organizational size diseconomies.

1.3.3 Productivity parameter k and minimum wage

Based on the numerator of (37), the equilibrium number of the involuntary solo self-employed decreases with the parameter k and with a lower minimum wage (higher m). These findings imply a lower number of involuntary solo self-employed.

1.4 Employees

The equilibrium number of employees is given by

Because (e 2/e M ) is independent of the extreme values of the uniform distribution, the sign of the effect of the changes in the mean and the variance of the distribution of skills on the equilibrium number of voluntary solo self-employed and employees is the same as for the aforementioned employers.

The number of employees decreases with k and increases with m (the term \( \frac{2(m - 1)}{2m - 1} \) in (38) increases with m).

1.5 Unemployment

Unemployment occurs when e s > e m . The number of individuals with a lower skills level that are unwilling to become solo self-employed in the economy is given by

Shifts to the right of the distribution of skills (with a constant variance) lower unemployment, but a higher variance for a given mean increases unemployment.

Unemployment increases with the reservation rent U and decreases with positive productivity shocks (higher θ) and higher k.

1.6 Average span of control

The endogenous variable of interest now is

The average span of control is independent of the bounds of the skills distribution and therefore independent of the mean and the dispersion of skills. The sign of the changes in the average span of control to changes in k an m is undetermined. The calculations indicate that the average span of control increases with parameter k and with a lower relative minimum wage (higher m). Furthermore, the higher organizational size diseconomies imply a lower average span of control, so long as (e 2/e M) also decreases with β.

1.7 Produced output

The endogenous variable is now the total produced output from (34). The output increases with the mean of the skills distribution for a given variance and with the variance in the skills for a given mean. The positive effect on the total output from the higher upper bound, e M + d, is higher than the negative effect from the change in the lower bound of the distribution, e M − d.

The total output decreases with β in the range of reasonable values. It increases with k and m (lower relative minimum wage).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Medrano-Adán, L., Salas-Fumás, V. & Sanchez-Asin, J.J. Heterogeneous entrepreneurs from occupational choices in economies with minimum wages. Small Bus Econ 44, 597–619 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9610-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9610-4