Abstract

This paper investigates strategic monitoring behavior within group lending. We show that monitoring efforts of group members differ in equilibrium due to the asymmetry between members in terms of future profits. In particular, we show that the entrepreneur with the highest future profits also puts in the highest monitoring effort. Moreover, monitoring efforts differ between group members due to free-riding: one member reduces her level of monitoring if the other increases her monitoring effort. This effect is also at play when we introduce a group leader into the model. The individual who becomes the group leader supplies more monitoring effort than in the benchmark case. We empirically test the model using data from a survey of microfinance in Eritrea and show that the group leader attaches more weight to future periods than nonleaders in the group, which may explain why a large part of total monitoring is done by the leader.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Lack of access to credit is generally seen as one of the main reasons why many people in developing economies remain poor. Usually, the poor have no access to loans from the banking system, because they cannot put up acceptable collateral and/or because the costs for banks of screening and monitoring the activities of the poor, and of enforcing their contracts, are too high to make lending to this group profitable. Since the late 1970s, however, the poor in developing economies have increasingly gained access to small loans with the help of so-called microfinance programmes. Especially during the past 10 years, these programmes have been introduced in many developing economies. Between December 1997 and December 2005 the number of microfinance institutions increased from 618 to 3,133. The number of people who received credit from these institutions rose from 13.5 million to 113.3 million (84% of them being women) during the same period (Daley-Harris 2006).

Many microfinance programs are characterized by so-called joint liability. With joint liability lending the group of borrowers is made responsible for the repayment of the loan; if one group member does not repay her loan, others may have to contribute so as to ensure repayment. In many cases, groups are small, consisting of 5–10 members. The broad consensus in the economic literature is that it mitigates problems of asymmetric information related to providing loans. However, most theoretical models on joint liability lending take a rather simple approach as to how group lending mitigates these problems. Basically, most models assume that all members monitor each other and that monitoring efforts of members are equal.

Usually, one of the members of the group is appointed to become the group leader, a position for which anyone from the group may volunteer. The group leader may have different tasks and the exact contents of these tasks may differ among group lending programs. However, the group leader usually is the intermediary between the group and the program staff, who regularly reports to the program’s staff on the performance and sustainability of the group. Moreover, the group leader usually chairs group meetings, collects the installment payments from group members and transfers them to the credit officer, visits group members regularly and discusses business- and/or group-related problems, and calls for extra group meetings if repayment problems occur. Again, depending on the characteristics of the group lending program, group leaders may or may not be paid for their activities.

Existing literature has hardly dealt with the specific role of the group leader as part of the group lending mechanism. However, based upon the above description, it seems reasonable to assume that in most cases the group leader plays a prominent role in the functioning of the group. Many questions remain unanswered, though, such as why someone wants to become group leader, whether they contribute to mitigating moral hazard behavior, and whether or not they help improving the repayment performance of groups. Whereas the latter two questions have been addressed empirically in two recently published papers (Hermes et al. 2005 and 2006), the first issue remains unresolved. Given the fact that the activities of the group leader are costly and assuming that she/he is not financially paid for these activities, the question arises why someone would volunteer to become group leader. We present a theoretical model that explains why this is the case. We also provide preliminary evidence supporting the main outcomes of the theoretical model.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly describes the main characteristics of existing models of joint liability lending. In Sects. 3–8 we provide a new theoretical framework analyzing group interaction, particularly focusing on strategic behavior of individual group members, as well as of the group leader. Section 3 describes the basic model for a group lending programme with three asymmetric borrowers. In Sect. 4 we derive the condition stating that moral hazard is present if there is no peer monitoring. Section 5 presents the monitoring technology, for both the group leader and the other group members. Section 6 discusses the benchmark case in which there is no group leader. In Sect. 7, we introduce a group leader and derive equilibrium monitoring levels for the case in which the most profitable entrepreneur is the leader, as well as for the case in which the second most profitable individual becomes the group leader. Section 8 endogenizes on the choice of group leadership. This is followed by a preliminary empirical test of the model in Sect. 9. Section 10 concludes.

2 Joint liability lending

Generally speaking, microfinance programmes provide credit to the poor, either through joint liability group lending, or through individual-based lending. While the latter comes close to traditional banking, involving a direct relationship between the programme and an individual, the joint liability lending approach uses groups of borrowers to which loans are made. Currently, the majority of microfinance borrowers have access to loans through group lending programmes. According to one recent survey of a sample of microfinance programmes, only 16% of these made use of so-called group lending to provide credit to the poor, yet they served more than two-thirds of all borrowers from the microfinance programmes included in the survey (Lapenu and Zeller 2001).

With joint liability lending the group of borrowers is made responsible for the repayment of the loan, i.e., all group members are jointly liable. Thus, if one group member does not repay her loan, others may have to contribute so as to ensure repayment. Nonrepayment by the group means that all group members will be denied future access to loans from the programme. In this way, group lending creates incentives for individual group members to screen and monitor other members of the group and to enforce repayment in order to reduce the risk of having to contribute to the repayment of loans of others and to ensure access to future loans. Thus, joint liability group lending stimulates screening, monitoring, and enforcement of contracts among borrowers, reducing or erasing the agency costs of the lender. Moreover, the group lending structure is also expected to be more effective in providing such activities as compared with the lender, because group members usually live close to each other and/or have social ties (also referred to as social capital in the existing literature). They are therefore better informed about each other’s activities. Since joint liability group lending stimulates screening, monitoring, and enforcement within the group, and since it improves the effectiveness of these activities due to geographical proximity and close social ties, repayment performance of group loans is expected to be high.

Several theoretical models confirm that joint liability group lending leads to increasingly more effective screening, monitoring, and enforcement among group members. Some of these models explicitly focus on the properties of joint liability lending related to mitigating information asymmetries. For example, models by Stiglitz (1990) and Varian (1990), Banerjee et al. (1994), Armendáriz de Aghion (1999), and Chowdhury (2005) explicitly deal with moral hazard and monitoring problems, showing how joint liability may help to solve these problems. Ghatak (1999, 2000) and Gangopadhyay et al. (2005), among others, provide models focusing on adverse selection and screening. Some other models specifically discuss the role of social ties within group lending in improving repayment performance of groups. The work of Besley and Coate (1995) and Wydick (2001) falls into this category of models.

Despite the fact that there are several theoretical analyses explaining how joint liability group lending may solve problems of information asymmetry, there are hardly any models explicitly focusing on different types of interaction between group members and the consequences for individual behavior. In particular, models do not pay attention to strategic behavior of individuals within a group. Existing theoretical models typically assume that the lending group consists of only two identical persons. In this setting, peer monitoring is necessarily mutual in order to make the joint liability contract work (Armendáriz de Aghion 1999). However, if the group consists of more than two members, the monitoring effort of an individual member may well depend on the monitoring effort of her peers, giving rise to the possibility of strategic behavior.

The model of Armendáriz de Aghion (1999) provides the first attempt to study the monitoring behavior of individuals in a lending group with more than two borrowers. In her setup, the group consists of three individuals who all can monitor each other to see whether one is unable or unwilling to meet her debt repayment, or stated differently, whether or not a group member defaults strategically. The model focuses on the partial equilibrium in which one of the group members is monitored by the other two. The two monitoring individuals are assumed to be symmetric, leading to a unique symmetric equilibrium in which both monitors put in an equal level of monitoring.

However, in reality, interests of group members may diverge, which may lead to asymmetric monitoring incentives. One clear example of this is the situation in which expected future profits are different for different group members. If this is the case, members have different interests in having access to future loans from the program. This in turn gives members different incentives to monitor the other group members. These different incentives among individuals to monitor each other may also explain why some individuals volunteer to become a group leader.

The model we present in the following sections makes use of the idea that group members may strategically behave when it comes to monitoring each other to explain why individuals volunteer for being the group leader, even if this is a costly task. In particular, we investigate strategic decisions concerning peer monitoring in a group lending program with three borrowers. We start by assuming that the lending group consists of three asymmetric entrepreneurs and that these entrepreneurs only differ from each other with respect to the future profits their projects generate. It is also assumed that the two individuals with the highest future payoffs put high effort into their projects to increase the probability that the loan is continued. The borrower with the project that has lowest future profitability shirks on putting effort into her project if she is not monitored, because the higher disutility when supplying more effort dominates the higher expected (future) profits due to the increased probability that the loan is continued. This thus gives the other two borrowers an incentive to monitor. In the benchmark model, in which there is no group leader, we obtain that in equilibrium the individual with the highest future payoffs provides the highest level of peer monitoring. This is due to two effects. First, the borrower with the highest expected future profits cares most about the continuation of the loan, which gives her the highest incentive to monitor. Second, because both monitors take into account each other’s optimal monitoring strategies, the second most profitable entrepreneur reduces her monitoring effort as a result of the high monitoring effort provided by the most profitable borrower. Vice versa, given the lower level of peer monitoring of the second most profitable entrepreneur, the most profitable borrower increases her monitoring effort even more. Analogously to quantity in a strategic duopoly, monitoring effort levels are strategic substitutes.

Next, we introduce the presence of a group leader. This means that one of the individuals in the group has to become the group leader, or otherwise the group cannot be formed. We argue that, despite the obligation to fulfil various tasks, being a group leader can be beneficial, because the leader has extra monitoring options that the nonleaders do not have; for example, a group leader chairs group meetings, plans meetings when there are repayment problems, etc. Assuming a convex monitoring cost function, these extra monitoring options reduce the per-unit costs of monitoring effort.

We first show that, in the presence of a group leader, and assuming that it is exogenously determined who the leader will be, the equilibrium monitoring effort of the borrower who now is the leader is higher than in the benchmark case, while the level of peer monitoring of the nonleader is lower. This is due to the fact that monitoring is a strategic substitute. Second, we find that, in the case in which the choice of group leadership is endogenous, the individual with the highest future payoffs under certain circumstances volunteers to be the group leader, even if she has to incur a disutility of performing the cumbersome tasks that come with the leadership. Due to the more efficient monitoring, the leader exerts more monitoring effort on the individual with the least profitable project to increase the probability that the loan will be continued.

3 The basic model

We consider three risk-neutral entrepreneurs who have the option to invest in a risky project, but need funds from a risk-neutral outside investor (hereafter, the bank) to finance the investment project. These entrepreneurs are denoted by A, B, and C and initially have no wealth. The funds needed by each entrepreneur are normalized to 1. In the remainder of the analysis the debt repayments, denoted by d G, are exogenously given in such a way that the expected profits of the bank are always zero or positive.Footnote 1 Furthermore, A, B, and C can only obtain funds if they form a lending group together. If it is required by the lending program, the group must choose one member to be the group leader, otherwise the group will not be formed and projects are cancelled.

In the first period that the project is carried out, the expected payoff of a project only depends on the effort supplied by the entrepreneur who undertakes this specific project. Let p j be the probability that the project will be a success with effort level j, where j = H, L, and p H > p L . The difference between these probabilities is given by Δp = p H − p L . In this context, j is the effort level of the project-specific entrepreneur and is therefore the single determinant of probability of success. Next, R 1 > 0 is the first-period payoff of the project when the project succeeds and R 1 = 0 is the output when the project is not successful. This first-period payoff is equal for all three entrepreneurs. The expected returns for the three group members in the first period become μ j = p j R 1, with Δμ = ΔpR 1. However, putting in high effort gives the entrepreneurs more disutility than putting in low effort. We monetize this disutility from providing effort by defining a parameter c j , j = H, L, and Δc = c H − c L > 0.

If each borrower repays her debt, all group members obtain a new loan, which is needed to continue the project in the following period. If one or more group members default on their debt, the nondefaulting member has to repay for them, otherwise the group lending program is stopped. If the projects are continued, the payoffs in the next period, denoted by R i2 , i, i = A, B, C are not the same across group members. Moreover, entrepreneurs B and C cannot perfectly observe the second-period payoffs of A, but do know that A’s payoffs in the second period are randomly distributed on the interval [0, M]. It is assumed that A herself exactly knows what her second-period payoffs are. For ease of exposition and because our analysis is concentrated on B and C monitoring A, we assume that the payoffs in the second period of B and C are perfectly observable by all and are equal to R B2 = 2M and R C2 = 3M, respectively. This means that, in the second period, C’s project is always more profitable than B’s project, and therefore it is in the best interest of C that the loan be continued.Footnote 2

Next, it is assumed that B and C always put in high effort, independently of the actions of the other group members, and moreover it is assumed that A always shirks on putting in effort if she is not monitored. The conditions for these assumptions to hold are stated in the next section. The latter assumption means that the moral hazard problem is present, giving group members B and C a reason to monitor member A. A monitor imposes a social cost Z on someone who is caught shirking. The probability that someone who monitors catches a shirking peer is given by γ i . The monitor herself can choose this probability and will always choose γ i = 1 if choosing so does not come at a cost, because this gives the maximal threat of a social sanction to the peer who is monitored.Footnote 3 However, we will assume that monitoring is costly, which means that setting a higher probability for detecting a shirking group member also means higher costs. The crucial aspect in the analysis is the assumption that the per-unit monitoring costs are lower for the group leader than for the nonleaders in the group, which may work as an incentive to become the group leader. In the next section, we treat this issue in more detail.

The model consists of four periods and the timing is as follows: at t = 0, the entrepreneurs form a group, (if needed) decide on who becomes the group leader, and borrow the funds from the bank.Footnote 4 In the next period each entrepreneur chooses the effort to put into the project and the monitoring effort. At t = 2, payoffs are realized and the total debt claim is paid off if at least one entrepreneur is successful. The bank continues the loan only if all loans are repaid. A social sanction Z is imposed if someone is caught providing low effort. At t = 3, the entrepreneurs realize a certain payoff R i2 in case the projects were continued at t = 2 and a zero payoff otherwise. Hereafter, the world ends.

4 Moral hazard

First, we show under what condition the moral hazard problem exists in this model. In this context, moral hazard occurs if entrepreneur A provides low effort, given that entrepreneurs B and C do not monitor A. This leads B and C to monitor A’s behavior, because low effort by A reduces their expected profits. In order to derive the condition for the existence of moral hazard, we determine the optimal choices for entrepreneur A. As we have already assumed, B and C will always choose to provide high effort, so that the total payoffs for A equal

The first element of π A j gives the expected profits for A when all projects turn out to be successful. Note that, in this situation, A only has to repay her own debt claim and joint liability plays no role in this case. For the following case, A does have to repay for one of her peers, because this peer was not successful, while A (and B or C) was. We assume that each of the successful ones come up with half of the debt claim the bank has on the defaulting peer. In the third case, A even has to pay for both peers, because she was the only one who had a positive payoff. The fourth element gives profits if A’s project failed, but at least one of her peers is able to repay for her. Notice that, although A does not obtain any profits in the first period, the second-period profits are obtained due to the joint liability structure of the loan. In the last case, none of the entrepreneurs were successful, which results in the loan being stopped at t = 1 and second-period profits cannot be obtained. From this, we get that the expected payoff for entrepreneur A flowing from the project is given by

To ensure that the moral hazard problem is present, we assume throughout the paper that

Assumption 1

Assumption 1 assures that A always puts in low effort if she is not monitored. Therefore, B and C have an incentive to monitor A, given that the social cost that can be imposed on A if she is caught shirking is high enough. Moreover, from assumption 1 we know that B and C always supply high effort, because they both have second-period profits at least as high as 2M, which is higher than the benefits from providing low effort.

5 Monitoring technology

In the previous section, we stated that group members B and C always fully monitor if monitoring is costless. However, this assumption is not realistic, which is why we only consider the case where monitoring is costly. To see why someone who monitors others incurs costs, notice that monitoring requires putting in efforts, devouring (a substantial amount of) resources and time that the group member could otherwise have spent on her own project. As we shall demonstrate below, the crucial aspect in our model is that the group leader has a different monitoring cost function than the nonleaders within the group. More formally, we state that the monitoring cost function of a nonleader in the group is given by

while for a leader the monitoring cost function is denoted by

where γ i is the individual monitoring effort of entrepreneur i, i = B, C, and κ is an efficiency parameter; it is assumed that this parameter is the same for B and C. From this, we get that in our analysis the per-unit monitoring costs are lower for the group leader than for the nonleaders.

To justify the different cost functions for the leader and nonleader, we argue the following: it is fair to say that the group leader has at least all the monitoring options the others have, and very likely, has some extra options the others do not have. As was explained above, a group leader chairs group meetings, plans meetings when there are repayment problems, etc. Moreover, it is assumed that the additional monitoring options available to the group leader are as effective as the options all group members (i.e., the leader and the nonleaders) have, which means that these additional options can be treated as a duplication of the monitoring possibilities of the nonleaders. Next, we argue that the monitoring options are subject to a decline in marginal effectiveness, hence the quadratic term in the cost functions. Solving the simple cost-minimization problem of the group leader shows that the leader divides her monitoring effort equally over the different options, which results in the cost function given by Eq. 3.

In the next section we first discuss the case in which the group does not have a group leader and all group members have the same monitoring cost functions. The results we obtain from this case are mainly used as a benchmark case, which we compare with the results we get if we model the presence of the group leader.

6 Monitoring without group leadership

In the case when there is no group leader, B and C have the same cost function, which is given by Eq. 2. To determine the optimal monitoring efforts, we not only have to know the cost structure of monitoring, but also the benefits of it. Clearly, the benefits of monitoring are that the probability that A will supply high effort increases, given that the monitor can impose a high enough social sanction on A if A is caught shirking. Note that the probability that A is monitored effectively by at least one peer equals ΓA = 1 − (1 − γ B)(1 − γ C), which means that B’s decision to monitor clearly depends on C’s monitoring decision and vice versa. Given that they both provide high effort, the extra profits B and C make when A supplies high effort equal

with i = B, C.

From this, we can see that the extra profits B and C make when A provides high effort equal the difference in probability of success times a term that both depends on joint liability and second-period profits. Remember that we assumed that the second-period profits are always higher for C than for B. This means that B and C are asymmetric in the sense that they have a different valuation for A’s effort level. As we will see below, this results in an asymmetric equilibrium. The extra profits that B and C make if A puts in high effort have to be multiplied by the change in probability that A provides high effort to calculate the expected profits of monitoring. Therefore, the net expected profits of supplying monitoring effort γ i equal

with i = B, C.

For the sake of exposition, we use \( x \equiv {{\left( {\left( {1{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}} - p_{H} } \right)p_{H} d^{\rm G} + 2(1 - p_{H} )^{2} M} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {\left( {1{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}} - p_{H} } \right)p_{H} d^{\rm G} + 2(1 - p_{H} )^{2} M} \right)} M}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} M} \) and \( y \equiv {{\left( {\left( {1{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}} - p_{H} } \right)p_{H} d^{\rm G} + 3(1 - p_{H} )^{2} M} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {\left( {1{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}} - p_{H} } \right)p_{H} d^{\rm G} + 3(1 - p_{H} )^{2} M} \right)} M}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} M} \) in the remainder of the analysis. Maximizing expected profits with respect to monitoring efforts yields first-order conditionsFootnote 5

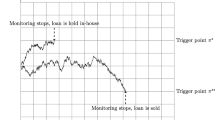

These first-order conditions can be seen as reaction functions, as both entrepreneurs make their monitoring decision dependent on the monitoring level of the other. Moreover, the levels of monitoring effort are strategic substitutes in the sense that an entrepreneur reduces her monitoring effort if the other increases her effort (see also Fig. 1). We can then formulate the following proposition:

Proposition 1

Given that no one in the group is the leader and that entrepreneurs simultaneously decide on their monitoring effort, the entrepreneur with the highest second-period payoffs puts in the highest monitoring effort.

Proof

The proof is fairly simple. Substituting the first-order conditions into each other gives equilibrium monitoring efforts \( \gamma_{\text{B}} = {\frac{(\alpha \kappa \,-\, yZ)xZ}{{(\alpha \kappa )^{2}\, -\, xyZ^{2} }}} \) and \( \gamma_{\text{C}} = {\frac{(\alpha \kappa \,-\, xZ)yZ}{{(\alpha \kappa )^{2} \,-\, xyZ^{2} }}} \). We get that γ C > γ B if x < y, which holds by assumption. This gives that the entrepreneur with the highest second-period payoffs, which is C, puts in more monitoring effort than the one with the lower second-period payoffs, which is B. QED.

This result is due to two different causes. First, entrepreneur C has higher second-period payoffs, which means that she has more interest in the continuation of the loan than B and benefits more from the monitoring efforts. Secondly, because B knows that it is most beneficial for C that A is monitored effectively, she also realizes that C puts in a substantial amount of monitoring effort. This reduces the incentive for B to supply monitoring effort.

7 Monitoring with group leadership

In the above analysis, we abstracted from the issue of group leadership and assumed that the group did not need a group leader. However, in reality we often see that a lending group needs a leader, who is the intermediary between the outside investor and the group itself. As we already discussed, a leader is likely to have more monitoring options than the nonleaders, which reduces per-unit monitoring costs. If this is the case, it may be beneficial for an entrepreneur to become the group leader, even if being a group leader means having to perform some (other than monitoring) cumbersome tasks. The (utility) loss of executing these tasks is modeled by introducing the fixed costs F that the group leader has to incur. These fixed costs will be introduced in the model in the next section, where we endogenize the choice to become the leader. In this section, however, we exogenously determine who will be the group leader.

7.1 Monitoring with C as group leader

Suppose that entrepreneur C is the group leader. In this case the monitoring cost function of C is given by Eq. 3, while the monitoring cost function of B remains that given by Eq. 2. The expected profits of monitoring equal

where γ GLCB and γ GLCC are the monitoring efforts of B and C, respectively, when entrepreneur C is the leader. The first-order conditions boil down toFootnote 6

We can formulate the following proposition:

Proposition 2

Given that the entrepreneur with the highest second-period profits becomes the group leader and that the entrepreneurs simultaneously choose their monitoring level, the leader now monitors more than in the case where there is no leader, while the nonleader monitors less compared with the situation in which there is no group leader.

Proof

From Eq. 8, we obtain equilibrium monitoring levels equal to \( \gamma_{\text{B}}^{\text{GLC}} = {\frac{(\alpha \kappa \,-\, 2yZ)xZ}{{(\alpha \kappa )^{2}\, -\, 2xyZ^{2} }}} \) and \( \gamma_{\text{C}}^{\text{GLC}} = {\frac{2(\alpha \kappa\, -\, xZ)yZ}{{(\alpha \kappa )^{2}\, -\, 2xyZ^{2} }}} \). Comparing these outcomes with the equilibrium levels when the group has no leader, we see that γ GLCB < γ B and γ GLCC > γ C if ακ > xZ, which holds by assumption. QED.

The intuition behind this is as follows: due to the lower monitoring costs and given a certain monitoring effort of B, C wants to monitor A more, i.e., her reaction function shifts outwards. Anticipating this, B supplies less monitoring effort than in the case where there is no leader. Notice that this is the result of the monitoring efforts being strategic substitutes (see also Fig. 2).

Although the per-unit costs of monitoring for C are lower in this case than if there is no group leader, it can be shown that the total monitoring costs of C are now higher due to the higher level of monitoring effort that C puts in.Footnote 7 One may think that, given this result, C is never willing to be the leader. Notice, however, that because of the different monitoring levels in both cases the probability that A is effectively monitored (and therefore the probability that A provides high effort) also differs between the cases. We get that if ακ > xyZ, this probability is higher in the case where C is the leader than when there is no leader in the group. Later, when we endogenize the choice of becoming the leader, we will be more specific about the equilibrium costs and benefits for C when she is the leader.

7.2 Monitoring with B as group leader

If B is the group leader, we can perform a similar kind of analysis as if C were the leader, but now with the monitoring cost function for B given by Eq. 3, while C’s monitoring cost function is stated by Eq. 2. We then come to the following proposition.

Proposition 3

If the entrepreneur with the lower second-period payoffs is the group leader, her monitoring effort is higher than in the case where there is no group leader, while the monitoring effort of the entrepreneur with the highest profits in the second period, i.e., the nonleader in this situation, is now lower. Moreover, the leader may monitor more or less than the nonleader, depending on the debt claim of the bank and the difference between the profits both entrepreneurs can generate in the second period. For our choice of second-period payoffs of B and C, R 2B = 2M andR 2C = 3M, the leader (B) puts in more monitoring effort than the entrepreneur with the highest second-period payoffs (C).

Proof

Again, from the first-order conditions we obtain equilibrium monitoring levels of B and C equal to \( \gamma_{\text{B}}^{\text{GLB}} = {\frac{2(\alpha \kappa \,-\, yZ)xZ}{{(\alpha \kappa )^{2}\, -\, 2xyZ^{2} }}} \) and \( \gamma_{\text{C}}^{\text{GLB}} = {\frac{(\alpha \kappa \,-\, 2xZ)yZ}{{(\alpha \kappa )^{2} \,- \, 2xyZ^{2} }}} \), respectively. Comparing these levels with the equilibrium levels in the case when there is no group leader gives that B monitors more and C monitors less if ακ > yZ, which holds by assumption. Next, the monitoring level of B is higher than the level of C if 2x > y, or if \( \left( {1{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}} - p_{H} } \right)p_{H} d^{\rm G} + (1 - p_{H} )^{2} (2R_{\text{B}}^{2} - R_{\text{C}}^{2} ) > 0 \). Substituting the exogenously given second-period returns into this condition gives \( \left( {1{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}} - p_{H} } \right)p_{H} d^{\rm G} + (1 - p_{H} )^{2} M > 0, \) which yields that for these payoffs B monitors more than C. However, if the difference in second-period payoffs is high and the debt claim is low, it may be that 2x < y, in which case the leader monitors less than the nonleader. QED.

Again, it can be shown that the total monitoring costs of the group leader are higher than in the case where there is no leader.

8 Endogenous choice of group leadership

In the above analysis it was exogenously given which entrepreneur would be the leader. However, if the group members are free to choose whether they will lead the group, in equilibrium all entrepreneurs follow their best strategy. We only focus on equilibria in which entrepreneur B and C are willing to become the group leader, otherwise there would be no leader and the group would not exist.Footnote 8 We then come to the following proposition.

Proposition 4

If the entrepreneur with the highest second-period payoffs volunteers to be the group leader, the entrepreneur with the lower profits in the second period always agrees with this. Therefore, we have a self-enforcing equilibrium in which the former will always be the group leader.

Proof

To see why it is always more profitable for B that C is the group leader instead of herself, notice that we already obtained that the total monitoring costs for B are higher if she herself is the leader than if C leads the group. Moreover, on the benefit side, the probability that A is monitored effectively is higher in the case that C takes the leadership than in the situation where B is the leader if (1 − γ GLCB )(1 − γ GLCC ) < (1 − γ GLBB )(1 − γ GLBC ). This condition is always satisfied given that y > x. Concluding, for B the costs are higher while the benefits are lower if B instead of C is the group leader, which makes it unprofitable for B to be the leader if C volunteers to lead the group. QED.

Now we have to determine under which condition entrepreneur C is willing to be the group leader. In contrast to B, there are two opposing effects for C if she is the group leader. On the one hand, being the leader means incurring a fixed cost and higher monitoring costs (F), but on the other hand, the probability of effective monitoring under C’s leadership is higher.

Proposition 5

If \( F < {\frac{{y\left( {{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}}y \,-\, x} \right)(\alpha \kappa Z)^{2} + (xyZ^{2} )^{2} }}{{((\alpha \kappa )^{2}\, -\, 2xyZ^{2} ){}^{2}}}}, \) entrepreneur C volunteers to lead the group. Footnote 9

Proof

As we already pointed out, if C leads the group instead of B the probability that A is monitored effectively is higher. Therefore, the extra benefits C makes by being the leader equal \( \Updelta \Uppi_{\text{C}} = \Uppi_{\text{C}}^{\text{GLC}} - \Uppi_{\text{C}}^{\text{GLB}} = {\frac{{\alpha^{2} \kappa^{3} yZ^{2} (y \,-\, x)}}{{((\alpha \kappa )^{2} \,-\, 2xyZ^{2} ){}^{2}}}} \). However, being the leader means incurring both a fixed cost F and higher total monitoring costs. For C, the extra costs of being group leader equal \( \Updelta C_{\text{C}} = C(\gamma_{\text{C}}^{\text{GLC}} ) - C(\gamma_{\text{C}}^{\text{GLB}} ) = {\frac{{\left( {{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}}(\alpha \kappa )^{2} \,-\, (xZ)^{2} } \right)(yZ)^{2} }}{{((\alpha \kappa )^{2} \,-\, 2xyZ^{2} ){}^{2}}}} \). This means that entrepreneur C volunteers to be the group leader if ΔΠ − ΔC – F > 0, or if \( F < {\frac{{y\left( {{\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}}y \,- \,x} \right)(\alpha \kappa Z)^{2} + (xyZ^{2} )^{2} }}{{((\alpha \kappa )^{2} \,-\, 2xyZ^{2} ){}^{2}}}} \). QED.

Figure 3 illustrates the extra profits entrepreneur C makes if she instead of B is the leader for parameter values p L = 0.2, p H = 0.5, κ = 8, and 0 ≤ M ≤ 10. For small values of M, the condition ακ > 2yZ is violated. For the feasible range of M we see that the extra profits decrease as M increases. The intuition behind this result is that, as M becomes bigger, the relative difference between the profitability of B’s project and C’s project, and therefore the difference in monitoring effort provided, becomes smaller. This means that the probability that A is monitored effectively is not much higher in the case that C is the leader than if B leads the group.

The main conclusions from the theoretical model is that the group member with the highest expected second-period payoff has the strongest incentive to volunteer to become the group leader, since the additional returns from increasing efforts to monitor A’s behavior are higher, taking into account the fact that B will lower monitoring efforts due to strategic behavior. These conclusions lead us to specify the following empirically testable hypothesis:

Hypothesis

Group members with projects that generate high future profits will volunteer to become the group leader. For these members future access to loans is more important, which means that they value future access to loans more highly than do other group members.Footnote 10

9 The role of the group leader: empirical evidence from Eritrea

9.1 Microfinance in Eritrea

In this next section, we test the hypothesis derived at the end of Sect. 8, using data from a questionnaire among individuals participating in two joint liability programs in Eritrea. In the year 2000 (the year in which we conducted our survey) there were two group lending programs operating in Eritrea. The Saving and Micro Credit program (SMCP) is active since 1996 and is part of the Eritrean Community Development Fund (ECDF), a government-related fund. The funding for this program comes from the Eritrean government, the World Bank, and from grants from a number of individual donor countries. The Southern Zone Saving and Credit Scheme (SZSCS) started in 1994 and was launched by the Agency for Co-operation and Research in Development (ACORD), a British nongovernmental organization (NGO). SMCP has activities all over the country, whereas SZSCS concentrates its efforts in the southern part of Eritrea.

The activities and organization of both programs are very similar. They are both active in rural as well as urban areas. The borrowers in both programs are active as retailers, farmers or small-scale producers. Both programs are set up along the lines of the Grameen Bank model. Groups are formed through self-selection; they consist of 3–7 members. After a group is accepted by one of the two programs, the group has to select a group leader. This selection is random, which means that in principle the group can select any one of its members and that any member can volunteer to become the leader. The group leader is the intermediary between the group and the program staff (i.e., the program’s credit officer and/or the village credit committee or bank). He/she has to regularly report to the program’s staff on the performance and sustainability of the group. Moreover, he/she has to chair group meetings, collect the installment payments from group members and transfer them to the credit officer, visit group members regularly and discusses business- and/or group-related problems, and call for extra group meetings if repayment problems occur. Based on this description of tasks, we conclude that the group leader plays a prominent role in the functioning of the group. Being a group leader is a voluntary activity; it does not generate any (financial) remuneration.

9.2 The data

During 2000 we conducted a survey among 111 groups, of which 59 were in SMCP and 52 were in SZSCS. Most of these groups were based in small villages and secondary towns of Eritrea. In the survey we asked questions about the socioeconomic characteristics of the group members, as well as about the saving and repayment performance of individual group members. In addition, we included questions on the group formation process, the existence of social ties, and on processes of screening, monitoring, and enforcement within groups. From each group we aimed at selecting the group leader and one or more other members to answer the questions.Footnote 11 Part of the questions was submitted to both the group leader and the other member(s) of each group; another part of the questions was specifically asked to the group leader. The survey was carried out only once, which means we have cross-sectional static data (i.e., only data for one year).

Through the questionnaire we obtained information from 351 group members, of whom 102 were group leaders. Of the total sample of group members, 167 were participating in the SZSCS program and 184 in the SMCP program. Within the sample, 196 borrowers were females (56%) and 155 were males. The majority (68%) of the respondents had no or only primary education. The average monthly income of group members was 1,017 Nakfas, the national currency of Eritrea (approximately USD 75Footnote 12). Trade (63%) and farming (17%) were the main occupations of group members; many of them usually had two (or more) occupations at the same time. On average, groups were composed of 4.5 members, with a median of four, ranging from a minimum of three to a maximum of seven members. The number of loan cycles (or loan rounds) that groups had completed up to the interview ranged from a minimum of two to a maximum of seven with an average of 3.6 cycles. Group loans ranged from 750 Nakfa (USD 54) to 8,500 Nakfa (USD 607), with mean and median loan size of 3,948 Nakfa (USD 282) and 3,500 Nakfa (USD 250), respectively. Loan terms varied from 3 to 24 months. Group members mainly used the loans for working capital purposes. Most respondents indicated they had never applied for a loan from a commercial bank.

Of the 102 group leaders, 46 were in a group in the SZSCS program and 56 in a group of the SMCP program; 54 of them were males (53%) and 48 were females. Group leaders’ income was somewhat higher (1,109 Nakfa, or USD 79) than the average income level of all group members in the sample. They were also very similar to the average group member in terms of occupation: 60% of them were active in trade, whereas 15% were active in farming.

9.3 The methodology

The survey allows us to investigate why an individual volunteers to become group leader. In the survey we have information on several characteristics of individual members such as age, sex, education, religion, marital status, income, primary activity, and whether they have access to finance other than microfinance. Moreover, we have information about the extent to which individuals know the other members of the group and whether they have prior information about them. We also have information about several group characteristics. However, in the context of this study, group-level characteristics cannot be used, since the dependent variable indicates whether or not an individual is the group leader, and every group has a group leader. This rules out the possibility of a multilevel analysis including both group- and individual-level characteristics.Footnote 13

Of particular interest for our analysis in this paper is a variable in the survey that indicates the value a group member attaches to having access to loans from the credit program in the future. This variable is called VFACCESS and takes values ranging from 1 (=very high value) to 4 (=very low value). Group members that value future access to loans higher than other members are expected to have projects that generate high future profits and they are therefore more willing to volunteer to become the group leader. If this is true, we expect to find a negative correlation between being a group leader and the value of VFACCESS (negative because of the way this variable has been measured).

To test this hypothesis of the negative relationship between being the group leader and VFACCESS, we set up an empirical model, in which the dependent variable LEADER is a dummy variable that takes a value of 1 if a group member is the leader and the value 0 otherwise. In the analysis, we use a probit estimator, which enables us to establish the determinants influencing the probability that someone is a group leader. Next to the variable VFACCESS we use a list of control variables measuring individual characteristics of group members that may influence the probability that someone is the group leader. In particular, we have three main groups of individual characteristics: one referring to personal characteristics, one referring to economic characteristics, and one referring to information that an individual has about the other group members.

The group of personal characteristics consists of the following variables:

-

AGE is the age of the group member (in years);

-

EDUCATION measures the educational background of the group member, ranging from 1 (=illiterate) to 4 (=has finished secondary education);

-

MARRIED is a dummy variable, being 1 if the group member is married and 0 if he/she is not; and

-

MOSLEM is a dummy variable, being 1 if the group member is a Moslem and 0 otherwise.

AGE is included in the model as it may be argued that there is a higher probability that older members are elected as the leader. Older members are more experienced and have more authority vis-à-vis younger group members. EDUCATION may be related to becoming the group leader: more highly educated members may have more authority based upon their knowledge skills vis-à-vis other members. MARRIED is included based on the premise that, if an individual is married and may thus have a family to support, he/she has more incentives to make the group successful in order to be able to obtain access to finance. Approximately half the Eritrean population is Sunni Moslem and the other half is Christian. For the religious dummy MOSLEM we have no a priori expectations with respect to how religion may influence the probability of someone becoming the group leader.

The economic characteristics are:

-

INCOME is the monthly income of the group member, in Nakfas;

-

CREDIT is a dummy variable taking the value 1 if the group member has had access to any other type of external finance (i.e., loans from a commercial bank, moneylender, family or friends, or trade credit) and 0 if this is not the case;

-

TRADER is a dummy variable, being 1 if the group member’s main occupation is being a trader and 0 otherwise; and

-

FARMER is a dummy variable, being 1 if the group member’s main occupation is being a farmer and 0 otherwise.

We include INCOME as an explanatory variable explaining why an individual may become group leader based on the idea that someone earning a higher income may be seen as more economically successful in the past, making this person the best candidate of being the leader. CREDIT is included because individuals having access to other financial sources may care less about obtaining microfinance loans, making them also less eager to become the group leader. We include TRADER and FARMER to take into account the potential effect that differences in economic activities may have on the probability of someone becoming the group leader.

Finally, the group of variables referring to the information that an individual has about the other group members consists of the following variables:

-

BORN is a dummy variable taking the value 1 if the group member was born in the same area where the survey was held and 0 if this is not the case;

-

KNOWACT is a dummy variable, being 1 if the group member indicates he/she has information about the activities of the other group members related to the use of the loan and 0 if he/she indicates not having this information;

-

KNOWMEM is a dummy variable, being 1 if the group member indicates he/she knew the other group members before the group was formed and 0 if he/she indicates this was not the case;

-

KNOWSALES is a dummy variable, being 1 if the group member indicates he/she knows the monthly sales of the other group members and 0 if this is not the case;

-

LIVE is the number of years that the individual has lived in the area where he/she was interviewed; and

-

CHGROUP is a dummy variable taking the value 1 if the group member indicates he/she has ever been a member of another group and 0 if this is not the case.

The above listed variables are all proxies for the extent to which an individual has information about his/her fellow group members and their activities and behavior. BORN, LIVE, and CHGROUP are indirect measures of having this type of information. If someone is born or has lived for a long time in the community where the group resides, he/she is expected to have more information about the people who live there. On the other hand, if an individual has changed groups one or more times, this may reduce the information he/she may have regarding the activities related to the use of the loan. KNOWACT, KNOWMEM, and KNOWSALES are more direct measures of the information an individual has about the activities and behavior of the other group members. The fact that an individual has more information about his/her fellow group members may give this individual an advantage vis-à-vis the other members, making him/her a potentially good candidate to become the group leader.

In conclusion, the complete empirical model can be specified as follows:

In this model, PERS is a vector of variables representing personal characteristics, ECON is a vector of variables referring to economic characteristics, and INFO is a vector of variables covering the informational characteristics of individual group members. Thus, in the complete version of the model we have 15 control variables, as well as the variable of interest, i.e., VFACCESS.

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics of the variables listed above. The table shows that majority of the group members attach a high value to future access to loans from the program, as the mean value of VFACCESS is 1.4 and the median is 1. As was discussed briefly above, most group members have no more than primary education: the mean of the variable EDUCATION is 2.1, and the median is 2. Most group members are married. A minority of them appears to be Moslem; this does not reflect the religious distribution in Eritrea, as half of the total population is reported to be Moslem. This may be due to the fact that the survey was carried out mainly in the highlands of the country, which is predominantly Christian. Most individuals report that they have no other sources of credit, meaning that access to credit from the microfinance programs may be important for them. Information about fellow group members, at least in terms of knowing them before they entered the group and knowing the type of their activities, is fairly high: 80–90% of the individuals in the sample report they have this type of information. At the same time, they have no information about the success of these activities: only 5% report having information about the monthly sales of their fellow group members. Finally, a small minority of the group members in our sample changed lending groups in the past.

In Table 4 in the appendix we provide the full correlation matrix of all variables we use in our empirical analysis. In general terms, the correlations reported in this table are low and we therefore do not expect to be confronted with problems of multicollinearity when running regression models.Footnote 14

9.4 Empirical results

Table 2 presents the results of the estimations. As was mentioned above, we apply the probit estimation methodology. The estimations are carried out as follows. First, we estimate the complete model, including all personal, economic, and informational variables, along with the variable of interest in the analysis, i.e., VFACCESS. Next, we delete variables for which we find the coefficient not being significant at the 10% level and re-estimate the reduced version of the model. We repeat this procedure until we are left with a model that only includes variables for which we find statistically significant coefficients.Footnote 15, Footnote 16

In the first column of Table 2 we show the estimations of the complete model. The results show that two variables are statistically significant. First of all, and most important in the context of our analysis, the variable of interest, i.e., VFACCESS, is significant and has the expected negative sign. This result supports our hypothesis that the probability of someone being a group leader is related to the value a group member attaches to having access to loans from the credit program in the future. Group members that value future access to loans more highly than other members (i.e., lower values of VFACCESS) are expected to have projects that generate high future profits and they are therefore more willing to volunteer to become the group leader. Next to this outcome, the variable EDUCATION is statistically significant and has a positive sign. We interpret this as evidence that individuals who have higher levels of education have a higher probability of being a group leader. Finally, the results in column [1] show that some of the other variables are sometimes close to being statistically significant; this holds for the variables MOSLEM, INCOME, and one of the two economic activity dummies (TRADER).

As explained in Sect. 9.3, the variable EDUCATION is measured using an ordinal scale that runs from 1 (the individual is illiterate) to 4 (the individual has finished secondary education). However, interpretation of this variable may be difficult, since it assumes that the distance between 1 and 2 is similar to the distance between 3 and 4. To come around this problem, we replace the EDUCATION variable by four dummy variables:

-

ILLITERATE is a dummy variable taking the value 1 if the individual is illiterate and 0 otherwise;

-

PRIMARY is a dummy variable taking the value 1 if the individual has finished primary education and 0 otherwise;

-

JSECONDARY is a dummy variable taking the value 1 if the individual has finished junior secondary education and 0 otherwise; and

-

SECONDARY is a dummy variable taking the value 1 if the individual has finished secondary education and 0 otherwise.

Next, we re-estimate the complete model, including three educational dummy variables.Footnote 17 The results are shown in column [2] of Table 2. The results are comparable to those presented in column [1]. Again, VFACCESS is negative and statistically significant. Moreover, the variable JSECONDARY is significant and positive, indicating that individuals having finished junior secondary education have a higher probability of being a group leader. We interpret this as evidence that higher levels of education are associated with someone becoming the leader. The other educational dummy variables are not statistically significant. The variable TRADER is also statistically significant and has a negative sign, indicating that being a trader reduces the probability that a person is the group leader. Finally, the variable MOSLEM is positive and significant, meaning that individuals who are Moslem have a higher probability of being a group leader. As was discussed in Sect. 9.3 we have no explanation for why there may be a positive association between being a Moslem and being a group leader. The other variables in the model are not statistically significant, although again the variable INCOME is relatively close to being significant.

The comment with respect to the interpretation of the variable EDUCATION may also apply to the variable VFACCESS. Again, we use an ordinal scale running from 1 to 4. When analyzing the distribution of the four values that VFACCESS can take, it turns out that the majority of the observations take the value 1 or 2. Whereas in 240 cases the value of VFACCESS is a 1 and in 91 cases it takes the value 2, in only 15 cases does it take the value 3 and in only 5 cases does it take the value 4. Therefore, we decided to create a new dummy variable (VFACCESS01), which takes the value 0 if VFACCESS is 1 and the value 1 if VFACCESS is 2, 3 or 4. Thus, we turn the ordinal variable into a variable that distinguishes between low and high levels of VFACCESS. With this newly created dummy variable we re-estimated the complete model. The results, shown in column [3], reveal that the outcomes are once again similar to those reported in columns [1] and [2]. The variable VFACCESS01 is statistically significant and has the expected sign. Thus, our main result is robust for different specifications of the access variable. Moreover, JSECONDARY, MOSLEM, and TRADER remain statistically significant and have the same sign as in the previous model outcomes. The results for the other variables are also in line with the ones shown earlier.

Next, we delete all variables for which we do not find statistically significant results. This leaves us with a model that only includes four variables: VFACCESS01, JSECONDARY, MOSLEM, and TRADER. If we run this reduced model (column [4]), the results show that the TRADER variable is no longer significant. The final result of the analysis is presented in column [5]. This model only contains variables for which we find significant results, i.e., VFACCESS01, JSECONDARY, and MOSLEM.

Based on the model presented in column [5], the conclusion we may draw is that, first of all, the probability of someone being a group leader is related to the value a group member attaches to having access to loans from the credit program in the future. This outcome is in line with the main message of our theoretical model presented in the first part of this paper. Moreover, higher levels of education, and especially having finished junior secondary education, is associated positively with being a group leader, indicating that higher educated members have more authority based upon their knowledge skills vis-à-vis the other members, making them better suited to become the group leader. Finally, being a Moslem is associated positively with being the leader. As we do not have a clear explanation for this finding, future research may focus on investigating what is behind this relationship. All other control variables fail to be statistically significant.

9.5 Robustness test

As a robustness test, we again analyze the relationship between being a group leader and the value a group member attaches to having access to loans from the credit program in the future, taking into account a potentially important personal characteristic, i.e., gender. This variable was not taken into account in the above analysis, since the groups in the Eritrean microfinance programs can be one of the three following types: all group members are men, all members are women, or members can have mixed gender (i.e., both men and women). The impact of gender on the probability of someone being a group leader can only be usefully studied for the mixed groups; for the all-men and all-women groups, the gender is determined by definition.

Therefore, as an additional control variable we add the variable GENDER to the vector of personal characteristics as specified in Eq. 1. GENDER is a dummy variable, being 1 if the group member is a male and 0 if the group member is a woman. We hypothesize that GENDER may be positively related to the probability of being the group leader. In the context of the cultural setting of the Eritrean society, which is still relatively traditional and patriarchal, men may have a higher chance of becoming group leader than women. Of the 111 groups, 47 consist of both male and female members (i.e., are mixed groups). In total, we have data for 167 individuals being member of one of these mixed groups.

We run exactly the same regression models as those presented in Table 2. The results are shown in Table 3. The main result of these additional analyses is that, first of all, the value of having access to future loans is an important determinant of the probability of someone being a group leader, which supports the results we reported in Table 2. Secondly, gender is also an important determinant of being a group leader. In particular, since the variable GENDER is significant and positive, being a male increases the probability of someone being a group leader, which confirms our hypothesis concerning the association between gender and leadership.Footnote 18 All other variables, including JSECONDARY and MOSLEM, are not statistically significant for the subsample of individuals who are members of mixed groups.Footnote 19

10 Conclusions

This paper has studied strategic monitoring behavior within a group lending setting, both for the case with and without the presence of a group leader. We have shown that in both cases the monitoring efforts of the borrowers in the group differ from each other in equilibrium, as a result of the asymmetry between these borrowers. The entrepreneur with the project that generates the highest future profits also puts in the highest monitoring effort. However, the difference between the effort levels of the two monitoring group members (B and C) is not only due to the difference in interest with respect to the continuation of the loan, but is also caused by a free-riding effect. Given that in our setting monitoring effort is a strategic substitute, one borrower reduces her level of monitoring if the other increases her monitoring effort.

This effect is also at play when we introduce a group leader into the model. The individual who becomes the group leader will supply more monitoring effort than in the benchmark case, because of the reduced per-unit monitoring costs. As a consequence, the nonleader free-rides on the higher level of monitoring of the leader and reduces her monitoring effort. We also obtained that, in equilibrium, the total monitoring costs of the leader are higher than in the benchmark case, even if the per-unit costs are lower. Still, it can be beneficial for the most profitable entrepreneur to volunteer to be the group leader. The probability that the least profitable borrower is monitored effectively in that case is higher than if another group member is the leader. Therefore, if the most profitable group member becomes the group leader, this maximizes the probability that the least profitable borrower puts high effort into her project. We point out that the results we have found are consistent with the empirical findings of Hermes et al. (2005). They conclude that, for the case of Eritrea, a large part of total monitoring is put in by the group leader.

We test our theoretical model using information from a survey we did among 351 group members of 111 lending groups in Eritrea in 2000. The survey allows us to investigate why an individual volunteers to become group leader. In the survey we have information on several characteristics of individual members such as age, gender, education, religion, marital status, income, primary activity, whether they have access to finance other than microfinance, and whether they have information about the other members of the group. Moreover, we have information about the value a group member attaches to having access to loans from the credit program in the future. This last variable allows us to empirically test the theoretical model. Individuals attaching higher value to having access to future loans from the program are expected to have projects that generate high future profits and may therefore have more incentives to repay group loans, thereby securing future access to finance. This, in turn, provides incentives to volunteer to become the group leader, as this position provides additional means to increase the probability of repayment of the group loan.

As explained in Sect. 9, the survey was carried out only once, which means we have cross-sectional static data (i.e., only data for one year). We acknowledge that this may be a shortcoming of the empirical analysis, since our aim is to analyze the dynamics of the group formation process. This means that, in order to qualify as a test of our theoretical model, we make two important assumptions. First, the group leaders we interviewed during the survey in 2000 were the same persons who were selected as leader when the group in which they participate was formed. Second, the perceptions regarding future profits of projects did not change since the group was formed.Footnote 20

If we accept this shortcoming of the available data, however, the results shown in Sect. 9 provide supporting evidence for the outcomes of the theoretical model. In particular, we find strong evidence that the probability of someone being a group leader is related to the value a group member attaches to having access to loans from the credit program in the future. This outcome is in line with the main message of our theoretical model presented in the first part of this paper. This main result is robust to different specifications of the access variable.

The paper should be seen as a first attempt to model strategic behavior in a group lending setting and, using our basic framework, to explain the voluntary aspect of group leadership. However, we are aware of the partial equilibrium character of our model, which is the result of the assumption that the two most profitable entrepreneurs always put high effort into their projects. Relaxing this assumption would result in a more general equilibrium in which every individual monitors but is also monitored herself. Moreover, the timing of the model could be adjusted, so that borrowers do not simultaneously decide on their monitoring effort. Notice that this may in fact reflect reality, as nonleaders might have a tendency to postpone the monitoring of peers until after the leader has monitored. This would make the group leader a Stackelberg leader in monitoring, which alters monitoring incentives within the group. Next, the entrepreneurs could be considered as being risk averse instead of risk neutral, which probably also changes the equilibrium levels of monitoring in the lending group. Our first idea is that, with risk-averse entrepreneurs, the total monitoring effort will be higher, because individuals want to minimize the risk that they lose future payoffs. However, it is not clear how this result may be influenced when there is a group leader. This needs to be investigated further. We leave this and other questions put forward above for future research.

Notes

The assumption that d G is exogenously given implies that the bank does not maximize profits. We assume that the bank breaks even if B and C put in high effort and A provides low effort, which is the case if there is no monitoring. Since in this case the expected payoff for the investor equals EΠBANK = 3((1 − (1 − p H )2(1 − p L ))d G − 1), the break-even condition boils down to d G = 1/(1 − (1 − p H )2(1 − p L )). As we will show below, there are situations in which A does provide high effort. The expected payoff for the bank then becomes EΠBANK = 3((1 − (1 − p H )3)d G − 1), which is strictly positive. Although we are aware of the fact that the zero-profit condition for the investor is a standard assumption in the literature, adopting this would heavily complicate our analysis, without yielding important additional insights. In this light, see Besley and Coate (1995) and Chowdhury (2005), who also take the debt claim as an exogenous parameter.

Because it does not change the analysis drastically, we consider for simplicity that the returns in the second period are independent of the effort level.

We assume that the entrepreneur who is monitored can perfectly observe the probability that she will be caught if she puts in low effort.

It is assumed that there is no discounting between periods.

We assume ακ > yZ, which ensures that 0 < γ B < 1 and 0 < γ C < 1. This means that we only have to consider interior solutions.

In this situation, we assume ακ > 2yZ, so that we again only consider interior solutions.

More formally, the monitoring costs for C in the case where there is no group leader equal \( C(\gamma_{\text{C}} ) = {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$\kappa $} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {\kappa 2}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$2$}}\left( {{\frac{(\alpha \kappa \,-\, xZ)yZ}{{(\alpha \kappa )^{2} \,- \,xyZ^{2} }}}} \right)^{2} , \) while C’s monitoring costs are \( C(\gamma_{\text{C}}^{\text{GL}} ) = {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$\kappa $} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {\kappa 4}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$4$}}\left( {{\frac{2(\alpha \kappa \,-\, xZ)yZ}{{(\alpha \kappa )^{2} \,-\, 2xyZ^{2} }}}} \right)^{2} \) if she herself is the group leader. The former is smaller than the latter if \( (\alpha \kappa )^{2} \left( {\sqrt 2 - 1} \right) + xyZ^{2} \left( {2 - \sqrt 2 } \right) > 0, \) which always holds.

Here, we assume that the costs of being the group leader F are high enough that it is never profitable for A to be the leader, even if the other two are not willing to lead the group. Moreover, we assume that F is low enough to ensure that B and C want to take the leadership if the group would otherwise not exist (see also footnote 9).

If the costs of being the group leader \( F \ge {\frac{{y(y/2 \,-\, x)(\alpha \kappa Z)^{2} + (xyZ^{2} )^{2} }}{{((\alpha \kappa )^{2} \,- \, 2xyZ^{2} )}}}, \) B and C need to negotiate about who will become the group leader. Since for C the stakes are higher, we expect that B has a better bargaining position and C ends up being the group leader. However, in this paper we abstract from bargaining issues and focus on the case where \( F < {\frac{{y(y/2 \,-\, x)(\alpha \kappa Z)^{2} + (xyZ^{2} )^{2} }}{{((\alpha \kappa )^{2} \,-\, 2xyZ^{2} )}}} \).

One referee pointed out that our model could also be used to explain the group formation process, i.e., the future leader may be the one who has mobilized the group. In this context, our model can be interpreted as follows: If the costs of leading the group are not too high, the entrepreneur with the highest expected second-period payoffs has incentives to form a group. She needs to form a group in order to be able to get access to a loan in the second period and realize her second-period project. Because of this she also has strong incentives to make sure the group makes it to the second period, meaning that she is willing to become the leader. The fact that she volunteers to become the leader enables her to attract other (less profitable) entrepreneurs to form a group. These less profitable entrepreneurs are willing to join the group, since the leadership (and the costs associated with this) is taken by the most profitable group leader, whereas at the same time they get access to finance as well. We thank the reviewer for pointing out this alternative interpretation of our model.

For 9 of the 111 groups we were unable to ask questions to the group leader.

Using an exchange rate of USD 1 = 14 Nakfa. This was the official exchange rate at the time the data for this research were gathered.

Group-level variables may, however, moderate the impact of individual characteristics on the probability of being the group leader. This possibility is investigated explicitly later on, when we investigate the impact of gender on the probability of someone being a group leader.

Correlations between the variables LIVE and AGE and between LIVE and BORN are relatively high (see bold values in the appendix table). These high values do make sense given the definitions of the variables. In the empirical analysis discussed below we ran regressions with and without inclusion of LIVE and AGE and/or LIVE and BORN at the same time. In both cases the regression results were almost exactly the same.

The econometric approach we have taken is also known as the general-to-specific approach and was suggested by the referee, for which we would like to think him/her. Another way of approaching the econometric modeling is to take the specific-to-general (or bottom-up) approach, which starts from a small model, including only theoretically correct variables and then tests various specifications of this smaller model. One important advantage of the general-to-specific approach is that “…the statistical consequences from excluding relevant variables are usually considered more serious than those from including irrelevant variables.” (Brooks 2002, pp. 209–210). We also used the alternative approach, starting with a specification that only includes the VFACCESS variable, and then subsequently adding the control variables one by one, until the complete model is specified. After estimating the complete model we then deleted all variables for which we are unable to find a statistically significant coefficient. This approach generates exactly the same outcomes as the ones we discuss in the main text. The results of the alternative approach are available from the authors on request.

In Table 2 we report the marginal effects of the independent variables on the dependent variable, instead of the coefficient estimations, because in the context of a probit model the marginal effects are more meaningful for considering the partial effects of the independent variables on the dependent variable.

The variable SECONDARY has been left out of the regression for reasons of singularity.

As one referee indicated, it would have been interesting to further analyze the impact of gender on the probability of being a group leader, for example by evaluating whether gender works differently in male- versus female-dominated groups. Unfortunately, our data do not allow us to test this. As explained in Sect. 9.2, we have information for the group leader and one or more other group members, meaning that we do not have information for all members in a group. This does not allow us to determine whether a mixed group is male or female dominated.

Admittedly, comparison of the results in Table 2 with those presented in Table 3 is somewhat difficult, because the results presented in Table 3 are based on a subsample of the data we have used to obtain the results presented in Table 2. This may explain why we find different results regarding the control variables in the two tables. Most importantly, however, the results regarding VFACCESS and VFACCESS01 remain unchanged in both sets of analyses.

In future work, we aim to analyze the dynamics of the group formation process as described in the theoretical model by using panel data, in which we actually know whether or not the group leader has changed since the group was formed and whether perceptions regarding future profits have remained constant over time.

References

Armendáriz de Aghion, B. (1999). On the design of a credit agreement with peer monitoring. Journal of Development Economics, 60, 79–104.

Banerjee, A., Besley, T., & Guinnane, T. (1994). Thy neighbor’s keeper: The design of a credit cooperative with theory and a test. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109, 491–515.

Besley, T., & Coate, S. (1995). Group lending, repayment schemes and social collateral. Journal of Development Economics, 46, 1–18.

Brooks, C. (2002). Introductory econometrics for finance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chowdhury, P. R. (2005). Group-lending: Sequential financing, lender monitoring and joint liability. Journal of Development Economics, 77, 415–439.

Daley-Harris, S. (2006). State of the microcredit summit campaign report 2006. Washington, DC: Microcredit summit campaign.

Gangopadhyay, S., Ghatak, M., & Lensink, R. (2005). Joint liability lending and the peer selection effect. The Economic Journal, 115, 1005–1015.

Ghatak, M. (1999). Group lending, local information and peer selection. Journal of Development Economics, 60, 27–50.

Ghatak, M. (2000). Screening by the company you keep: Joint liability lending and the peer selection effect. The Economic Journal, 110, 601–631.

Hermes, N., Lensink, R., & Mehrteab, H. T. (2005). Peer monitoring, social ties and moral hazard in group lending programmes: Evidence from Eritrea. World Development, 33, 149–169.

Hermes, N., Lensink, R., & Mehrteab, H. T. (2006). Does the group leader matter: The impact of monitoring activities and social ties of group leaders on the repayment performance of group-based lending in Eritrea. African Development Review, 18, 72–97.

Lapenu, C., & Zeller, M. (2001). Distribution, growth and performance of microfinance institutions in Africa, Asia and Latin America, FCND discussion paper 114, Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Stiglitz, J. (1990). Peer monitoring and credit markets. World Bank Economic Review, 4, 351–366.

Varian, H. (1990). Monitoring agents with other agents. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 146, 153–174.