Abstract

Technological activities of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have received considerable attention from researchers and policy makers since the mid-1980s. Small firms could nurture entrepreneurship and facilitate the creation and application of new ideas. In spite of their potential in generating innovations, it is also observed that SMEs shy away from formal R&D activities, and the firm size itself seems to be a barrier for R&D activities. SMEs operating in developing countries face extra hurdles to investing in R&D. Given the massive share of SMEs, it becomes crucial to realize their developmental potential in developing countries. In this paper, we study the drivers of R&D activities in SMEs in Turkish manufacturing industries by using panel data at the establishment level for the 1993–2001 period. Our findings suggest that SMEs are less likely to conduct R&D, but if they overcome the first obstacle of conducting R&D, they spend proportionally more on R&D than the LSEs do. R&D intensity is higher in small than in large firms. Moreover, public R&D encourages firms to intensify their R&D efforts. The impact of R&D support is stronger for small firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

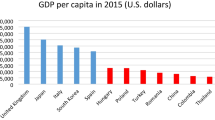

Privatization of public assets has attracted substantial FDI after 2002, and annual FDI inflows reached US$ 9.8 billion in 2005 and US$ 19.8 billion in 2006.

In the same period, imports increased at almost the same rate, from US$ 7.9 billion in 1980 to US$ 22.3 billion in 1990, and US$ 54.5 billion in 2000.

Number of employees is used as the size criterion. Establishments employing fewer than 250 people are classified as “small and medium-sized enterprise” (SME). Large-scale enterprises (LSE) employ 250 or more people. “Foreign firms” are those joint ventures where foreign ownership is 10% or more.

The economy achieved very high growth rates after the 2001 crisis (the average annual growth rate of GDP was 7% in 2002–2007).

There are a number of other schemes to support R&D activities. The Ministry of Finance allows for tax credits for R&D expenses. Up to 20% of the corporate taxes within the period of R&D activity can be delayed for 3 years without interest, provided that the delayed amount does not exceed the R&D expenditure. However, the number of firms applying for tax credits remained limited. For details, see SPO (2004). During the 1990s, Turkey introduced a number of new laws and regulations (a new law on intellectual property rights in 1994, the competition law in 1994, and the law on technology development zones in 2001), and several institutions that form the building blocks of a national system of innovation were established or reorganized.

The R&D Survey covers manufacturing and some service sectors (most importantly, the software sector). Since the ASMI covers only manufacturing, the data on non-manufacturing firms in the R&D survey and R&D support clients databases were not used. During the matching process for manufacturing firms, it is found that the data for some firms in the R&D database were missing in the ASMI database. However, the share of R&D expenses of these firms was less than 5% of total R&D expenses.

For example, one of the major R&D performers and the leading consumer durables producer, Arcelik, established its R&D division in 1991 (www.arcelik.com.tr/).

“Technology transfer” refers to transferring technology from abroad by know-how and license agreements.

We calculated capital stock at the firm level by using the perpetual investment method.

“Sector” is defined at the ISIC (revision 2) 4-digit level. “Region” refers to provinces in Turkey (NUTS 3-digit level). Some of the provinces with a few manufacturing establishments are merged together. These provinces are located mostly in the eastern part of the country.

Time dummies are included in all models to control for exogenous changes in R&D costs and macroeconomic shocks.

We use OECD’s classification of technology intensity. Since there are not many firms operating in high-tech industries, they are classified together with the medium-tech industries.

The GMM-System estimates with all variables (column 3 in Table 8) suggest that the R&D intensity model is not dynamic because the lagged R&D intensity variable has insignificant coefficients. In such a case, there is no need to use the GMM-System method because it is specifically developed for the estimation of dynamic models. When the size-lagged R&D intensity interaction is excluded from the model, the lagged R&D intensity variable becomes statistically significant (column 4).

This specification defines the change in the performance of R&D performers relative to the performance of non-performers in 1 year after conducting R&D. We also estimate 2-year performance (Pit+2 – Pit ), by comparing those that performed R&D at time t + 1 and t, but not at time t − 1, with those that did not perform R&D in any year from t − 1 to t + 1.

The “psmatch2” program by Leuven and Sianesi (2003) is used for propensity matching.

References

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1988). Innovation in large and small firms: An empirical analysis. American Economic Review, 78, 678–690.

Aerts, K., & Schmidt, T. (2008). Two for the price of one? Additionality effects of R&D subsidies: A comparison between Flanders and Germany. Research Policy, 37, 806–822.

Czarnitzki, D., & Fier, A. (2002). Do innovation subsidies crowd out private investment? Evidence from the German service sector. Konjunkturpolitik––Applied Economics Quarterly, 48, 1–25.

David, P. A., Hall, B. H., & Toole, A. A. (2000). Is public R&D a complement or substitute for private R&D? A review of econometric evidence. Research Policy, 29, 497–529.

De Negri, J. A., Lemos, M. B., & De Negri, F. (2006). Impact of R&D incentive program on the performance and technological efforts of Brazilian industrial firms. Office of Evaluation and Oversight Working Paper No. 14/06. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Duguet, E. (2004). Are R&D subsidies a substitute or a complement to privately funded R&D? An econometric analysis at the firm level. Revue d’Economie Politique, 112, 245–274.

González, X., & Pazó, C. (2008). Do public subsidies stimulate private R&D spending? Research Policy, 37, 371–389.

Hall, B., & van Reenen, J. (2000). How effective are fiscal incentives for R&D? A review of the evidence. Research Policy, 29, 449–469.

Heckman, J. J., LaLonde, R. J., & Smith, J. A. (1999). The economics and econometrics of active labor market programs. In A. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 3A, pp. 1865–2097). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Hyytinen, A., & Toivanen, O. (2005). Do financial constraints hold back innovation and growth? Evidence on the role of public policy. Research Policy, 34, 1385–1403.

Klette, T. J., Moen, J., & Griliches, Z. (2000). Do subsidies to commercial R&D reduce market failures? Microeconometric evaluation studies. Research Policy, 29, 471–495.

Lach, S. (2002). Do R&D subsidies stimulate or displace private R&D? Evidence from Israel. Journal of Industrial Economics, 50, 369–390.

Lenger, A., & Taymaz, E. (2006). To innovate or to transfer? A study on spillovers and foreign firms in Turkey. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 16, 137–153.

Leuven, E., & Sianesi, B. (2003). PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing (Version 3.0.0). http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html. Accessed 10 March 2008.

Lööf, H., & Hesmati, A. (2005). The impact of public funding on private R&D investment. New evidence from a firm level innovation study. Centre of Excellence for Studies in Science and Innovation Electronic Working Paper No. 06. Stockholm: The Royal Institute of Technology.

Mohnen, P., Nadiri, M. I., & Prucha, I. (1986). R&D production structure and productivity growth in the U.S., Japanese and German manufacturing sectors. European Economic Review, 30, 749–772.

Nadiri, M. I., & Schankerman, M. (1981). The structure of production, technological change and the rate of growth of total factor productivity in the bell system. In T. G. Cowing & R. E. Stevenson (Eds.), Productivity measurement in regulated industries (pp. 219–247). New York: Academic Press.

OECD. (2002). Frascati manual: Proposed standard practice for surveys of research and experimental development. Paris: OECD.

Özçelik, E., & Taymaz, E. (2008). R&D support programs in developing countries: The Turkish experience. Research Policy, 37, 258–275.

Potters, L., Ortega-Argilés, R., & Vivarelli, M. (2008). R&D and productivity: Testing sectoral peculiarities using micro data. IZA Discussion Paper No. 3338, Bonn.

Smith, J. A., & Todd, P. E. (2005). Does matching overcome LaLonde’s critique of nonexperimental estimators? Journal of Econometrics, 125, 305–353.

State Planning Organization (2004). Devlet yardımlarını değerlendirme özel ihtisas komisyonu raporu. SPO Publication No. 2681. Ankara: SPO.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the IPTS workshop on “Drivers and Impacts of Corporate R&D in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises” on September 19, 2008. We would like to thank our discussant Werner Bönte, the special issue editor Marco Vivarelli and workshop participants for their valuable comments and suggestions. This paper is partly based on an evaluation study on the effects of R&D support programs financed by the Technology Development Foundation of Turkey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Taymaz, E., Üçdoğruk, Y. Overcoming the double hurdles to investing in technology . Small Bus Econ 33, 109–128 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9181-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9181-y