Abstract

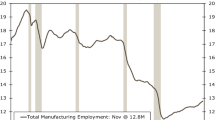

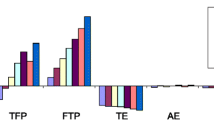

The German chemical manufacturing industry experienced major downsizing between 1992 and 2004, with the average size of firms shrinking by nearly half during this period. This study uses modern frontier efficiency analysis to investigate the determinants of this downsizing. Based on reliable census data, the results of this analysis suggest that firms were not primarily concerned with improving technical efficiency, but with establishing an optimal scale of production. The proportion of scale-efficient firms has been persistently increasing, and downsizing is found to be a rational conduct because all scale-inefficient firms have continually operated under the decreasing returns portion of technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This equality ensures that firm j is compared only to firms of similar size; such a convexity restriction is not utilized under a CRS assumption, where firms of different sizes might be compared, that is, \(\sum\nolimits^N_{j=1}z_j\) might be greater/smaller than unity.

This inequality ensures that firm j is not compared to other firms that are considerably larger, but it may be compared to smaller firms.

Scale efficiency measures how close the manufacturing firm is to its potentially optimal scale. The measure of scale efficiency for output orientation shows the expansion magnitude of output vector to the optimal scale on the estimated frontier.

Aggregate figures are published annually in Fachserie 4, Reihe 4.3 of Kostenstrukturerhebung im Verarbeitenden Gewerbe (German Federal Statistical Office various years). The data for year 1994 are not available.

Industry “Manufacture of chemicals, chemical products and man-made fibres,” NACE.24 in accordance with the Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community.

Though the production theory framework requires real quantities, using expenditures as a proxy for inputs in the production function is a practice often found in the literature (e.g., Paul and Nehring 2005).

Unfortunately, the Cost Structure Census does not give the number of hours worked, which is a conventional metric used as a proxy for labor. It does, however, give the number of employees; however, this number is not used in the analysis for the following reason. There is some evidence that manufacturing firms have increased outsourcing—Grossman and Helpman (2005) claim that “... Firms seem to be subcontracting an ever expanding set of activities, ranging from product design to assembly, from research and development to marketing, distribution, and after-sales service.” Using the number of employees would belie important information about the actual amount of labor used in the generating value added. Moreover, using aggregate labor compensation enables different qualities of labor to be accounted for.

In response to demand from the scientific community for microdata of official statistics in Germany, the Federal Statistical Office established Research Data Centers (http://www.forschungsdatenzentrum.de) in March 2002. Today, analysis of the representative data set can be accomplished at secured sites at 16 locations across Germany. All estimations for this article were carried out at the German Research Data Center in Berlin using remote computation.

Bias correction introduces additional noise (greater variance of bootstrapped scores), which might result in the mean-square error of the bias-corrected score being larger than that of simple DEA estimate. This is especially true for the multidimensional setting. Therefore Simar and Wilson (2008) propose not using bias-correction unless \(\frac{|\widehat{bias_j}|}{\sigma_j} > \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\) or more conservatively \(\frac{|\widehat{bias_j}|}{\sigma_j} > \frac{1}{4};\) where \(\sigma _{j}\) is the standard deviation of bootstrapped efficiency scores, \(\widehat{\theta}^*_{jb}.\) In the sample used here, in 1992, for example, the minimum, the mean, and the maximum of \(\frac{|\widehat{bias_j}|}{\sigma_j}\) are 1.103, 2.038, and 2.940, respectively, which indicates not very large variance of bootstrapped scores introduced by bootstrap procedure. This makes using bias-correction legitimate for this particular case.

The system of cross-holdings leads to ownership concentration, which is associated with weak corporate governance.

The full set of results appears in Appendix A (Electronic Supplementary Material).

The approach requires that the size of each of the n individual tests, α l , be chosen much smaller than the global or overall size of the test, α g . More specifically, \(\alpha_{l} =1-(1-\alpha_{g} )^{1/n}.\) For example, α l = 0.00007327 for n = 700 and α g = 0.05; α l = 0.0001505 for α g = 0.1.

Only in 1997 is one firm out of 220 scale inefficient due to increasing returns to scale

Such a closeness to 100% might make one doubtful about the power of the test. Hence, I looked at the raw, that is, not bootstrapped, values of η j (Eq. 13), which turned out to be approximately 0.98 on average. This is very close to 1, implying that, on average, distances to the VRS and NIRS frontiers are almost equal, which practically precludes the increasing returns to scale nature of scale inefficiency. Bootstrapped tests back this up.

In 1994, 54% of total sales went for exports.

These firms make up roughly 13% of all German chemical firms.

This is feasible since the inputs are in real monetary terms.

References

Alvarez, R., & Crespi, G. (2003). Determinants of technical efficiency in small firms. Small Business Economics, 20, 233–244.

Audretsch, D. B., & Elston, J. A. (1997). Financing the German Mittelstand. Small Business Economics, 9, 97–110.

Audretsch, D. B., & Elston, J. A. (2006). Can institutional change impact high-technology firm growth?: Evidence from Germany’s Neuer Markt. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 25(1), 9–23

Baily, M. N., Bartelsman, E.J., & Haltiwanger, J. (1996). Downsizing and productivity growth: Myth or reality? Small Business Economics, 8, 259–278.

Baily, M. N., Bartelsman, E.J., & Haltiwanger, J. (2001). Labor productivity: Structural change and cyclical dynamics. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(3), 420–433.

Baldwin, J. R. (1995). The dynamics of industrial competition: A North American perspective. NY: Cambridge University Press.

Banker, R. D. (1984). Estimating most productive scale size using Data Envelopment Analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 17(1), 35–44.

Bartelsman, E. J., & Doms, M. (2000). Understanding productivity: Lessons from longitudinal microdata. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), 569–594.

Bathelt, H. (1995). Global competition, international trade, and regional concentration: The case of the German Chemical Industry during the 1980s. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 13, 395–424.

Bathelt, H. (2000). Persistent structures in a turbulent world: The division of labor in the German Chemical Industry. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 18, 225–247.

Baumol, W. J., Panzar, J. C., & Willig, R. D. (1988). Contestable markets and the theory of industry structure. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Caves, R. E., & Barton, D. R. (1990). Efficiency in U.S. manufacturing industries. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cazals, C., Florens, J.-P., & Simar, L. (2002). Nonparametric Frontier estimation: A robust approach. Journal of Econometrics, 106, 1–25.

Daouia, A., & Simar, L. (2007) Nonparametric efficiency analysis: a multivariate conditional quantile approach. Journal of Economics, 140, 375–400.

Färe, R., & Grosskopf, S. (1985). A nonparametric cost approach to scale efficiency. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 87, 594–604.

Färe, R., Grosskopf, S, & Knox Lovell C. A. (1994a). Production Frontiers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Färe, R., Grosskopf, S., Norris, M., & Zhang, Z. (1994b). Productivity growth, technical progress, and efficiency change in industrialized countries. American Economic Review, 84(1), 66–83.

Färe, R., & Zelenyuk, V. (2003). On aggregate Farrell efficiencies. European Journal of Operational Research, 146, 615–620.

Farrell, M. J. (1957). The measurement of productive efficiency. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General), 120(3), 253–290.

Franks, J., & Mayer, C. (2001). Ownership and control of German Corporations. The Review of Financial Studies, 14(4), 943–977.

Freeman, C. (1990). Technical innovation in the world chemical industry and changes of techno-economic paradigm. In: C. Freeman, & L. Soete (Eds.), The new exploitations in the economics of technical change (chapter 4) (pp. 74–91). London: Pinter Publishers.

German Federal Statistical Office. (various years). Cost Structure Census (Kostenstrukturerhebung im Verarbeitenden Gewerbe), Vol. Fachserie 4, Reihe 4.3, Stuttgart: Metzler-Poeschel.

Grossman, G., & Helpman, E. (2005). Outsourcing in a global economy. Review of Economic Studies, 72, 135–159.

Helpman, E., & Rangel, A. (1999). Adjusting to a new technology: Experience and training. Journal of Economic Growth, 4, 359–383.

Kneip, A., Park, B. U., & Simar, L. (1998). A note on the convergence of non-parametric DEA estimators for production efficiency scores. Econometric Theory, 14, 783–793.

Kneip, A., Simar, L., & Wilson, P. W. (forthcoming). Asymptotics and consistent bootstraps for DEA estimators in nonparametric frontier models. Econometric Theory. doi:10.1017/S0266466608080651.

Kumar, J. (2003). Ownership structure and corporate firm performance. Working Paper Series, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research.

Landau, R., & Arora, A. (1999). The chemical industry: From the 1850’s until today. Business Economics, 34(4), 7–15.

Maindiratta, A. (1990). Largest size-efficient scale and size efficiencies of decision-making units in data envelopment analysis. Journal of Econometrics, 46, 57–72.

Nickell, S. J. (1996). Competition and corporate performance. Journal of Political Economy, 104(4), 724–746.

Paul, C. J. M., & Nehring, R. (2005). Product diversification, production systems, and economic performance in U.S. agricultural production. Journal of Econometrics, 126, 525–548.

Ray, S. C. (2007). Are some Indian banks too large? An examination of size efficiency in Indian banking. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 27(1), 41–56.

Ray, S. C., & Desli, E. (1997). Productivity growth, technical progress, and efficiency change in industrialized countries: Comment. American Economic Review, 87(5), 1033–1039.

Shephard, R. W. (1970). Theory of cost and production functions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Silverman, B. W. (1986). Density estimation for statistics and data analysis. London: Chapman and Hall.

Simar, L. (2003). Detecting outliers in Frontier models: A simple approach. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 20, 391–424.

Simar, L., & Wilson, P. W. (1998). Sensitivity analysis of efficiency scores: how to bootstrap in nonparametric Frontier models. Management Science, 44, 49–61.

Simar, L., & Wilson, P. W. (2002). Non-parametric tests of returns to scale. European Journal of Operational Research, 139, 115–132.

Simar, L., & Wilson, P. W. (2008). Statistical inference in nonparametric Frontier models: recent developments and perspectives. In H. O. Fried, C. A. Knox Lovell, & S. S. Schmidt (Eds.), The measurement of productive efficiency (chapter 4, pp. 421–521). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swift, T. K. (1999). Where is the chemical industry going? Business Economics, 34(4), 32–41.

Wenger, E., & Kaserer, C. (1998). The German system of corporate governance: A model which should not be imitated. In S. W. Black & M. Moersch (Eds.), Competition and convergence in financial markets: The German and Anglo-American Models (chapter 3, pp. 41–78). Amsterdam: North-Holland Elsevier Science.

Weston, J. F., Johnson, B. A., & Siu, J. A. (1999). Mergers and acquisitions in the global chemical industry. Business Economics, 34(4), 23–31.

Acknowledgments

The research on this project benefited from comments by Tom Coupé, Roy Gardner, Christian Hirschhausen, and Andreas Stephan. The research also benefited from comments from participants of the 4th International Industrial Organization Conference, the North American Productivity Workshop IV, the 33rd EARIE Conference, and the Comparative Analysis of Enterprise (Micro) Data (CAED) Conference, 2006. I also thank Ramona Pohl at the German Research Data Center in Berlin for support and help with this project, and the two referees for valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Badunenko, O. Downsizing in the German chemical manufacturing industry during the 1990s. Why is small beautiful?. Small Bus Econ 34, 413–431 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9142-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9142-x