Abstract

The paper proposes a descriptive model of firm growth which assumes that learning processes are conditional on existing competencies of the firm and its founders. We suggest the idea that firms who do not grow under all realizations of potentially profitable opportunities can be considered as zero-learning. In order to explain why some firms are zero-learning and how these are different from growing ones, we put forward and discuss the hypothesis that both start-up size and founders’ pre-entry history affect the firm’s ability to adjust to market. Using a sample of 3,905 Italian firms born in 1999 and 2000, we find that individual competencies influence start-up size, but not directly growth. We also find a significant nonlinear relationship between start-up size and growth, implying that firms which were born smaller than a given size grow significantly less. The results support the hypothesis that multiple and heterogeneous growth processes coexist and that the growth process of microfirms below a given organizational threshold may be structurally different, in the long run, from that of firms starting up above that threshold.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

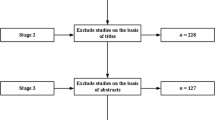

Unioncamere carried out several waves of surveys. However in this work we use the surveys on firms born in 1999 and 2000 only, since the questionnaires, which have been partially modified across waves, better suit our research interests.

The cleaning procedure followed the EUROSTAT guidelines, which recommend the classification of a new firm registration as “true” whenever it is not possible to find an existing firm sharing with the new one two features out of: (i) location, (ii) sector of activity, and (iii) team of founders. The share of false entries in each cohort of new Italian firms in period 1998–2000 was, on average, 40% (Osservatorio Unioncamere sulla demografia delle imprese 2003, p. 10).

The number of observations drawn from each stratum was determined as the average between proportional and optimal sampling.

The refusal rate was about 11% in the two surveys. This unusually high response rate may be explained by considering the institutional role of the Chambers of Commerce in the business sector.

Firms that were classified as nonsurviving by the interviewer (on the basis of firm’s statements) do not need to be formally deleted from the Businesses Register. Indeed, the definition does not refer to the administrative status of the firm. Nonsurviving firms are those: (i) which definitively stopped their activity (11.58%), (ii) whose activity is temporarily “suspended” (1.54%), (iii) that have not started their activity yet (0.79%), and (iv) other (0.18%).

Unfortunately, we do not have information on turnover or value added. Indeed, according to Italian law, firms with the legal form of “ditta individuale” do not need to complete a formal public balance sheet. The large majority of firms in the sample fall into this category. As a result, we were unable to match our data with public data on balance sheets to obtain measures of firm performance other than workforce growth.

On the same grounds, we acknowledge the ongoing debate about possible distortions in firm growth process due to Italian employment protection law (EPL), which introduced more severe rules for dismissing employees in firms having more than 15 employees. Recent empirical evidence shows that possible “threshold effects” around 15 employees in the size and growth distribution of Italian firms is quantitatively negligible (Schivardi and Torrini 2004; Boeri and Jimeno, 2005).

According to official statistics, construction is the only sector where an uncommonly high employment growth rate took place during the observation period, thus indicating a possible regularization effect (ISTAT 2002, ISTAT 2003a). We checked the robustness of all empirical results with the exclusion from the sample of the construction sector.

In our opinion, the selected criterion is valid in distinguishing firms that show significant growth over the sample period from all the others, both in terms of the univariate distribution of absolute and relative growth, and consistent with previous empirical literature (see, as examples, Cooper et al. 1994; Bruderl and Preisendorfer 2000). We adopted several thresholds to test the robustness of results. No significant departures from the results showed in this section have been observed.

In order to remove the problems of biased estimates and artificially small standard errors that would arise whenever the stratification design is not included in the analysis we adopt a pseudo-maximum-likelihood estimation. This accounts for complex survey designs, adopting the linearization method for deriving standard errors. The linearization method uses a first-order Taylor series to approximate standard errors, which are nonlinear functions of the population parameters (Levy and Lemeshow 1999).

The estimation has been run after deleting from the sample the observations reporting missing values in the explanatory variables, thus reducing the number of usable cases to 3,075.

References

Acs, Z., & Audretsch, D. B. (1987). Innovation, market structure and firm size. Review of Economics and Statistics, 69(4), 567–574.

Aldrich, H. (1999). Organizations evolving. London: Sage.

Åstebro, T., & Bernhardt, I. (2005). The winner’s curse of human capital. Small Business Economics, 24(1), 63–78.

Atkeson, A., & Kehoe, P. J. (2002). Measuring organizational capital. NBER WP 8722.

Bhattacharjee, A. (2005). Models of firm dynamics and the hazard rate of exits: Reconciling theory and evidence using hazard regression models. CRIEFF Discussion Papers 0502, Centre for Research into Industry, Enterprise, Finance and the Firm.

Black, S. E., & Lynch, L. M. (2005). Measuring organizational capital in the new economy. In C. Corrado, J. Haltiwanger, & D. Sichel (Eds.), Measuring capital in the new economy. National Bureau of Economic Research Studies in Income and Wealth, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Boeri, T., & Jimeno, J. F. (2005). The effects of employment protection: Learning from variable enforcement. European Economic Review, 49(8), 2057–2077.

Bruderl, J., & Preisendorfer, P. (1998). Network support and the success of newly founded business organizations. Small Business Economics, 10, 213–225.

Bruderl, J., & Preisendorfer, P. (2000). Fast growing businesses. International Journal of Sociology, 30(3), Fall, 45–70.

Buenstorf, G., & Klepper, S. (2005). Heritage and agglomeration: The akron tire cluster revisited. Papers on Economics and Evolution 2005–08, Max Planck Institute of Economics, Evolutionary Economics Group.

Cabral, L. M., & Mata, J. (2003). On the evolution of the firm size distribution: Facts and theory. American Economic Review, 93(5), 1075–1091.

Carpenter, R. E., & Rondi, L. (2006). Going public to grow? Evidence from a panel of Italian firms. Small Business Economics, 27, 387–407.

Caves, R. E. (1998). Industrial organization and new findings on the turnover and mobility of firms. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(4), 1947–1982.

Colombo, M. G., Delmastro, M., & Grilli, L. (2004). Entrepreneurs’ human capital and the start-up size of new technology-based firms. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 22(8–9), 1183–1211.

Colombo, M. G., & Grilli, L. (2005). Does founders’ human capital affect the growth of new technology-based firms? A competence-based perspective. Research Policy, 34, 795–816.

Cooper, A. C., Gimeno-Gascon, J. F., & Woo, C. Y. (1994). Initial human and financial capital as predictors on new venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 371–395.

Duchesneau, D. A., & Gartner, W. B. (1990). A profile of new venture success and failure in an emerging industry. Journal of Business Venturing, 5(5), 297–312.

Dunne, T., Roberts, M. J., & Samuelson, L. (1988). Patterns of firm entry and exit in US manufacturing industries. RAND Journal of Economics, 19(4), 495–515.

Dunne, T., Roberts, M. J., & Samuelson, L. (1989). The growth and failure of U.S. manufacturing plants. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4), 671–698.

Ericson, R., & Pakes, A. (1995). Markov-perfect industry dynamics: A framework for empirical work. Review of Economic Studies, 62(1), 53–82.

Evans, D. S. (1987a). The relationship between firm growth, size and age: estimates for 100 manufacturing firms. Journal of Industrial Economics, 35(4), 567–581.

Evans, D. S. (1987b). Tests of alternative theories of firm growth. Journal of Political Economy, 95(4), 657–674.

Evans, D. S., & Jovanovic, B. (1989). Estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), 808–827.

Fagiolo, G., & Luzzi, A. (2006). Do liquidity constraints matter in explaining firm size and growth? Some evidence from the Italian manufacturing industry. Industrial and Corporate Change, 15(1), 1–39.

Fazzari, S. M., Hubbard, R. G., & Petersen, B. C. (1988). Financing constraints and corporate investment. Brooking Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 141–195.

Gibrat, R. (1931). Les inegalites economiques. Paris: Librairie du Recueil Sirey.

Gimeno, J., Folta, T. B., Cooper, A. C., & Woo, C. Y. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(4), 750–783.

Hall, B. H. (1987). The relationship between firm size and firm growth in the US manufacturing sectors. Journal of Industrial Economics, 3(4), 583–606.

Harhoff, D. (1998). Are there financing constraints for R&D and investment in german manufacturing firms? Annales d’Economie et de Statistique, 49/50.

Harhoff, D., Stahl, K. M., & Woywode, M. (1998). Legal form, growth and exit of West German firms. Empirical results for manufacturing, construction, trade and service industries. Journal of Industrial Economics, 46(4), 453–488.

Helfat, C. E., & Lieberman, M. B. (2002). The birth of capabilities: Market entry and the importance of pre-history. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(4), 725–760.

Helfat, C. E., & Raubitschek, R. S. (2000). Product sequencing: Co-evolution of knowledge, capabilities and products. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 961–980.

Hvide, H. K. (2005). Firm size and the quality of entrepreneurs. CEPR Discussion Papers 4979.

ISTAT. (2002). Rilevazione trimestrale delle forze lavoro. Roma: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica.

ISTAT. (2003a). Rilevazione trimestrale delle forze lavoro. Roma: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica.

ISTAT. (2003b). La Misura dell’Occupazione non Regolare nelle Stime di Contabilità Nazionale: un’Analisi a Livello Nazionale e Regionale. Anni 1992–2001. Roma: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50(3), 649–670.

Klepper, S. (2001). Employee startups in high-tech industries. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(3), 639–674.

Klepper, S. (2002). The capabilities of new firms and the evolution of the US automobile industry. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(4), 645–665.

Klepper, S., & Sleeper, S. (2005). Entry by spinoffs. Management Science, 51(8), 1291–1306.

Lazear, E. P. (2002). Entrepreneurship. NBER Working Paper No. W9109.

Levy, P. S., & Lemeshow, S. (1999). Sampling of populations (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Lippman, S. A., & Rumelt, R. P. (1982). Uncertain imitability: An analysis of interfirm differences in efficiency under competition. Bell Journal of Economics, 13(2), 418–438.

Lotti, F., & Santarelli, E. (2004). Industry dynamics and the distribution of firm sizes: A non-parametric approach. Southern Economic Journal, 70(3), 443–466.

Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (1994). Life duration of new firms. Journal of Industrial Economics, 42(3), 227–245.

Nås, S. O., & Sandven, T. (2005). Innovation and FIRM DEMOGRAPHY: Two aspects of industrial renewal. Mimeo.

Nås, S. O., Sandven, T., Eriksson, T., Andersson, J., Tegsjö, B., Lehtoranta, O., & Virtaharju, M. (2003). High-tech spin-offs in the Nordic countries: Main report. STEP report 23-2003.

Osservatorio Unioncamere sulla Demografia delle Imprese. (2003). Le Nuove Imprese in Italia nel Triennio 1998–2000. Roma: Centro Studi.

Pakes, A., & Ericson, R. (1998). Empirical implications of alternative models of firms dynamics. Journal of Economic Theory, 79(1), 1–45.

Reynolds, P. D. (1997). Who starts new firms? Preliminary explorations of firms-in-gestation. Small Business Economics, 9, 449–462.

Roberts, E. B. (1991). Entrepreneurs in high technology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schivardi, F., & Torrini, R. (2004). Firm size distribution and EPL in Italy. Bank of Italy Discussion Paper 504.

Shane, S. (2000). Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organization Science, 11(4), 448–469.

Shane, S. (2001). Technological opportunities and new firm creation. Management Science, 47(2), 205–220.

Shane, S. (2003). A general theory of entrepreneurship. The individual-opportunity nexus. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Signorini, L. F. (2000). Lo Sviluppo Locale. Un’Indagine della Banca d’Italia sui Distretti Industriali. Roma: Donzelli.

Stuart, R. W., & Abetti, P. A. (1990). Impact of entrepreneurial and management experience on early performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 5, 151–162.

Sutton, J. (1997). Gibrat’s legacy. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(1), 40–59.

Thompson, P., & Klepper, S. (2005). Spinoff entry in high-tech industries: Motives and consequences. Working Papers 0503, Florida International University, Department of Economics.

Traù, F. (Ed.). (1999). La Questione Dimensionale nell’Industria Italiana. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Von Hippel, E. (1988). The sources of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wagner, J. (1994). The post-entry performance of new small firms in German manufacturing industries. Journal of Industrial Economics, 42(2), 141–154.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bonaccorsi, A., Giannangeli, S. One or more growth processes? Evidence from new Italian firms. Small Bus Econ 35, 137–152 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9131-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9131-0