Abstract

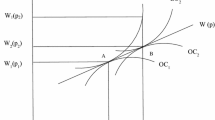

Our research clarifies the conceptual linkages among willingness to pay for additional safety, willingness to accept less safety, and the value of a statistical life (VSL). We present econometric estimates using panel data to analyze the VSL levels associated with job changes that may affect the worker’s exposure to fatal injury risks. Our baseline VSL estimates are $7.7 million and $8.3 million (Y$2001). There is no statistically significant divergence between willingness-to-accept VSL estimates associated with wage increases for greater risks and willingness-to-pay VSL estimates as reflected in wage changes for decreases in risk. Our focal result contrasts with the literature documenting a considerable asymmetry in tradeoff rates for increases and decreases in risk. An important implication for policy is that it is reasonable to use labor market estimates of VSL as a measure of the willingness to pay for additional safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See U.S. Office of Management and Budget Circular A-4, Regulatory Analysis (Sept. 17, 2003), which is available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars_a004_a-4 (Last accessed July 24, 2013); Memorandum to Secretarial Officers Modal Administrators from Polly Trottenberg, Under Secretary for Policy and Robert S. Rivkin, General Counsel, Guidance on Treatment of the Economic Value of a Statistical Life in U.S. Department of Transportation Analyses, Office of the Secretary of Transportation, U.S. Department of Transportation, 2013. Available at http://www.dot.gov/office-policy/transportation-policy/guidance-treatment-economic-value-statistical-life (Last accessed July 24, 2013); and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Valuing Mortality Risk Reductions for Environmental Policy: A White Paper,” SAB Review Draft, 2010.

For minor health effects that do not reduce the marginal utility of income, Chilton et al. (2012) report stated preference evidence indicating a narrowing of the WTA/WTP gap for more minor health effects.

If workers have a beta distribution of assessed fatal injury risks where γ is the informational content of the prior and p0 reflects the probability of an adverse outcome, the posterior probability of p *0 that prevails after observing information equivalent to one unfavorable trial outcome is (γp0 + 1)/(γ +1) > p0.

When there is time-invariant non-random attrition, the differenced data models we use will remove it along with other latent time-invariant factors (Ziliak and Kniesner 1998).

In Kniesner et al. (2012) the estimated VSL from the pooled model that included job stayers is $6.6 million. Although this is statistically the same as the pooled VSLs reported in Tables 1 and 2 here, the qualitatively lower point estimate results from dampened variation in industry/occupation fatal risk among job stayers.

A worker moving to a riskier job that poses an additional 5/100,000 risk will receive an added wage premium of $350, which is 0.7% of average annual income. Based on estimates of the income elasticity of VSL (Viscusi and Aldy 2003), the effect of such income changes on the VSL will be under 0.5%.

As part of specification checks we ran regressions similar to those in Table 1 for persons who did not change jobs. In all cases estimated VSL was either insignificant or negative. Additionally, results similar to those in Table 1 (symmetry of estimated VSL) appear when we include a dummy variable for positive change in fatal injury rate so the linear segments need not join at a common point. For more discussion of the general econometric issue see Hamermesh (1999).

Note that the subsample of “when change jobs” might involve more complicated time-varying effects, as we discuss below.

References

Altonji, J. H., & Paxson, C. H. (1988). Labor supply preferences, hours constraints, and hours-wage trade-offs. Journal of Labor Economics, 6(2), 254–276.

Bai, J. (2009). Panel data models with interactive fixed effects. Econometrica, 77(4), 1229–1279.

Brown, C. (1980). Equalizing differences in the labor market. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 94(1), 113–134.

Chilton, S., Jones-Lee, M., McDonald, R., & Metcalf, H. (2012). Does the WTA/WTP ratio diminish as the severity of a health complaint is reduced? Testing for smoothness of the underlying utility of wealth function. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 45(1), 1–24.

Hamermesh, D. S. (1999). The art of labormetrics. NBER Working Paper 6927.

Horowitz, J. K., & McConnell, K. E. (2002). A review of WTA/WTP studies. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 44(3), 426–447.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Knetsch, J. L., & Tang, F.-F. (2006). The context, or reference, dependence of economic values. In M. Altman (Ed.), Handbook of contemporary behavioral economics: Foundations and developments (pp. 423–440). New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

Knetsch, J. L., Riyanto, Y. E., & Zong, J. (2012). Gain and loss domains and the choice of welfare measure of positive and negative changes. Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis, 3(4). doi:10.1515/2152-2812.1084.

Kniesner, T. J., Viscusi, W. K., Woock, C., & Ziliak, J. P. (2012). The value of statistical life: Evidence from panel data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(1), 74–87.

Kőszegi, B., & Rabin, M. (2006). A model of reference-dependent preferences. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(4), 1133–1165.

Lillard, L. A., & Weiss, Y. (1979). Components of variation in panel earnings data: American scientists 1960–70. Econometrica, 47(2), 437–454.

List, J. (2003). Does market experience eliminate market anomalies? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 41–71.

Plott, C. R., & Zeiler, K. (2005). The willingness to pay-willingness to accept gap, the “endowment effect”, subject misperceptions, and experimental procedures for eliciting valuations. American Economic Review, 95(3), 530–545.

Schaffner, S., & Spengler, H. (2010). Using job changes to evaluate the bias of value of statistical life estimates. Resource and Energy Economics, 32(1), 15–27.

Solon, G. (1986). Bias in longitudinal estimation of wage gaps. NBER Working Paper 58.

Villanueva, E. (2007). Estimating compensating wage differentials using voluntary job changes: evidence from Germany. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 60(4), 544–561.

Viscusi, W. K. (1979). Employment hazards: An investigation of market performance. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Viscusi, W. K. (2004). The value of life: estimates with risks by occupation and industry. Economic Inquiry, 42(1), 29–48.

Viscusi, W. K. (2013). Using data from the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries to estimate the “value of a statistical life”. Monthly Labor Review, 1–17.

Viscusi, W. K., & Aldy, J. E. (2003). The value of a statistical life: a critical review of market estimates throughout the world. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 27(1), 5–76.

Viscusi, W. K., & Huber, J. (2012). Reference-dependent valuations of risk: why willingness-to-accept exceeds willingness-to-pay. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 44(1), 19–44.

Viscusi, W. K., Magat, W., & Huber, J. (1987). An investigation of the rationality of consumer valuations of multiple health risks. RAND Journal of Economics, 18(4), 465–479.

Ziliak, J. P., & Kniesner, T. J. (1998). The importance of sample attrition in life-cycle labor supply estimation. Journal of Human Resources, 33(2), 507–530.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Jack Knetsch provided insightful suggestions. This research was conducted with restricted access to BLS data. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the BLS

Appendix A

Appendix A

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kniesner, T.J., Viscusi, W.K. & Ziliak, J.P. Willingness to accept equals willingness to pay for labor market estimates of the value of a statistical life. J Risk Uncertain 48, 187–205 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-014-9192-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-014-9192-1