Abstract

The paper exploits the “Mad Cow” crisis as a natural experiment to gain knowledge on the behavioral effect of new health information. The analysis uses a detailed data set following a sample of households through the crisis. The paper disentangles the effect of non-separable preferences across time from the effect of previous exposure. It shows that new health information interacts in a non-monotonic way with disease susceptibility. Individuals at low or high risk of infection do not respond to new health information. The results show that individual behavior partly offsets the effect of new health information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Consumers learned about the crisis on March 20, 1996, so their reactions to the news are observed during 13 weeks. This is enough to study their immediate reaction but not longer term behavior.

Adda and Cornaglia (2006) document a related trade-off for tobacco consumption.

The country of origin of the beef was not recorded, because, up to 1997, it was not legal to reveal the country of origin to the consumer for “fear of distortions” on the beef market. Yet, shortly after the crisis, the French retail industry set up a label on domestic beef, which was assumed to be safer than foreign beef. In April 1996, the consumer had then the choice between French and foreign beef, but the precise origin of the foreign beef was not indicated. At the time of the crisis, French cows had also been diagnosed with BSE, so it is not clear whether the label was very meaningful. There is no indication that the introduction of this label changed the aggregate demand for beef.

With hindsight, this does not appear to be a rational behavior as these cuts are closer to the spine and therefore more likely to lead to contamination. However, at the time of the crisis, there was not extensive knowledge about the transmission of the disease, especially among consumers.

In France, the awareness of a link between beef, cholesterol and coronary heart diseases (CHD) is lower than in many other countries. France has the lowest rate of CHD in the world together with Japan. The rate is about three times lower than in the USA, and four times lower than in the UK. The consumption of beef is mostly determined by cultural differences across regions.

The first stage indicates that the instruments have power with F tests with associated p values of 0 for all endogenous variables.

We do not find statistical evidence of gender differences for younger children.

However, the fact that parents cannot split from their teenagers gives these children some bargaining power.

We also estimated a tobit model which takes into account the truncation at zero, as expenditures cannot be negative. Consumers with a small stock might have little scope to reduce their consumption, which might explain why they respond less to the crisis. We found that the results are comparable to the one in Table 3.

We are grateful to W. Kip Viscusi for suggesting this point.

Becker and Mulligan (1997) discuss the case of an endogenous discount factor.

References

Adda, Jérôme and Francesca Cornaglia. (2006). “Taxes, Cigarette Consumption and Smoking Intensity,” American Economic Review 96(4), 1013–1028.

Antoñanzas, Fernando, W. Kip Viscusi, Joan Rovira, Francisco J. Braña, Portillo Fabiola, and Iirineu Carvalho. (2000). “Smoking Risks in Spain: Part I Perception of Risks to the Smoker,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 21(2/3), 161–186.

Becker, Gary S. and Casey B. Mulligan. (1997). “The Endogenous Determination of Time Preference,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(3), 729–758.

Becker, Gary S. and Kevin M. Murphy. (1988). “A Theory of Rational Addiction,” Journal of Political Economy 96(4), 675–699.

Bourguignon, François. (1999). “The Cost of Children: May the Collective Approach to Household Behavior Help?” Journal of Population Economics 12(4), 503–521.

Browning, Martin and Pierre-André Chiappori. (1998). “Efficient Intra-Household Allocations: A General Characterization and Empirical Tests,” Econometrica 66(6), 1241–1278.

Chesher, Andrew. (1997). “Diet Revealed? Semiparametric Estimation of Nutrient Intake-Age Relationships,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 160(3), 389–428.

Deaton, Angus and John Muellbauer. (1980). “An Almost Ideal Demand System,” American Economic Review 70(3), 312–326.

Ehrlich, Isaac and Hiroyuki Chuma. (1990). “A Model of the Demand for Longevity and the Value of Life Extension,” Journal of Political Economy 98(4), 761–782.

Farrell, Phillip and Victor Fuchs. (1982). “Schooling and Health: The Cigarette Connection,” Journal of Health Economics 1, 217–230.

Green, Peter J. and Bernard W. Silverman. (1994). Nonparametric Regression and Generalised Linear Models: A Roughness Penalty Approach. London: Chapman and Hall.

Gruber, Jonathan. (2001). “Risky Behavior among Youth: An Economic Analysis.” In Jonathan Gruber (ed), Risky Behavior Among Youth: An Economic Analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hurd, Michael, Daniel MacFadden, and Angela Merrill. (2001). “Predictions of Mortality among the Elderly.” In David Wise (ed), Themes in the Economics of Aging. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hurd, Michael D. and Kathleen McGarry. (1995). “Evaluation of the Subjective Probabilities of Survival in the Health and Retirement Study,” Journal of Human Resources 30(0), S268–292.

Hurd, Michael D. and Kathleen McGarry. (2002). “The Predictive Validity of Subjective Probabilities of Survival,” Economic Journal 112(482), 966–985.

Khwaja, Ahmed, Frank Sloan, and Sukyung Chung. (2006). “The Effects of Spousal Health on the Decision to Smoke: Evidence on Consumption Externalities, Altruism and Learning within the Household,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 32(1), 17–35.

McElroy, Marjorie. (1990). “The Empirical Content of Nash Bargained Household Behavior,” Journal of Human Resources 25, 559–583.

Nichèle, Véronique and Jean-Marc Robin. (1995). “Simulation of Indirect Tax Reforms Using Pooled Micro and Macro French Data,” Journal of Public Economy 56, 225–244.

Pollak, Robert A. (1970). “Habit Formation and Dynamic Demand Functions,” Journal of Political Economy 78(4), 745–763.

Viscusi, W. Kip and Joni Hersch. (2001). “Cigarette Smokers as Job Risk Takers,” Review of Economics and Statistics 83(2), 269–280.

Viscusi, W. Kip (1990). “Do Smokers Underestimate Risks?” Journal of Political Economy 98(6), 1253–1269.

Viscusi, W. Kip (1993). “The Value of Risks to Life and Health,” Journal of Economic Literature 31, 1912–1946.

Viscusi, W. Kip (1997). “Alarmist Decisions with Divergent Risk Information,” The Economic Journal 107, 1657–1670.

Viscusi, W. Kip, Welsey A. Magat, and Joel Huber. (1987). “An Investigation of the Rationality of Consumer Valuations of Multiple Health Risks,” Rand Journal of Economics 18(4), 465–479.

Viscusi, W. Kip and Michael J. Moore. (1989). “Rates of Time Preference and Valuations of the Duration of Life,” Journal of Public Economics 38, 297–317.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I am grateful to SECODIP, the Observatoire des Consommations Alimentaires, to Christine Boizot for research assistance, to Gary Becker, Russell Cooper, Christian Dustmann, Valérie Lechene, Costas Meghir, Jean-Marc Robin, W. Kip Viscusi, Tim Besley, an anonymous referee and to seminar participants at Boston University, ESEM, Harvard University, INRA, INSEE, LSE, University of Bristol, University of Chicago, University College London and University of Toulouse for comments and suggestions. The usual disclaimer applies.

Appendix

Appendix

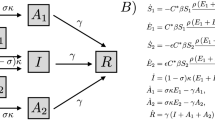

The first order condition of model 1 is:

where u i and V i denote the partial derivative of the utility function and second period indirect utility function with respect to the ith argument. First differentiating this expression gives:

which can be written more compactly as:

so that:

Standard restrictions on the shape of the utility function imply that u i > 0, u ii < 0, V i > 0, V ii < 0. Moreover, the definition of the survival probability implies that \(\partial \pi(S,\kappa)/\partial S=\pi_1\le 0\) and that \(\partial \pi(S,\kappa)/\partial \kappa=\pi_2\le 0\), if individuals perceive that nvCJD is a threat to life.

If u 12 ≥ 0 (beef and other meat products are complements) and the relationship between survival and beef consumption is concave (π 11 ≤ 0, then \(\tilde{A}_B\le 0\), \(\tilde{A}_p\le 0\) and \(\tilde{A}_y \ge 0\). The effect of health information on consumption of beef is equal to:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adda, J. Behavior towards health risks: An empirical study using the “Mad Cow” crisis as an experiment. J Risk Uncertainty 35, 285–305 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9026-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9026-5