Abstract

This paper reports results from an economic experiment where respondents are asked to make choices between risky outcomes for themselves and others. We investigate whether subjects’ own risk preferences and gender stereotypes are reflected in the predictions they make for the risk preferences of others and the way this occurs. When predicting other people’s risk preferences, the respondents tend to use a combination of their own risk preferences and stereotypes. Moreover, when making risky choices for others, the respondents generally use a combination of their own risk preferences and their average predicted risk preference of the targeted group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The paper by Chakravarty et al. (2005) came to our attention after the experiments in this study were performed.

The default hypothesis is analogous to the false consensus effect in social psychology where people tend to overestimate the degree to which their own behaviour, attitudes, beliefs etc. are shared by other people (Ross, Greene and House 1977).

In the Chakravarty et al. study, respondents were required to predict the average risk propensity of the other participants by guessing the average choice made by all participants.

See Siegrist, Cvetkovich and Gutscher (2002) and references therein for results from studies testing the risk-as-value hypothesis.

See Loewenstein et al. (2001) for a detailed description of the Risk-as-feelings theory.

Hsee and Weber (1997) find that the risk-as-feelings hypothesis holds when the target is anonymous. However, in a second study, they find that when respondents are asked to predict the risk preferences of an individual visible to them, the results are consistent with the default hypothesis. The authors explain the results by arguing that it is easier for individuals to project their own feelings towards risk in the case where the target is vivid than when the target is abstract.

The authors conducted an experiment where subjects were required to make abstract gambling decisions as well as financially motivated risky decisions embedded in an investment or insurance context.

In addition they point out those results from survey data showing gender specific risk attitudes may be due to differences in individuals’ opportunity sets. This theory is supported partly by the results of Säve-Söderbergh (2003) who studied premium pension portfolio choices and found that, after controlling for a wide range of variables, the only significant gender difference appeared at the upper end of the risk distribution.

Eckel and Grossman also refer to a model developed by Vesterlund (1997) where if more risk-averse workers can be identified, then they (women if the stereotype is applied) face a distribution of wages that is stochastically dominated by the distribution for the less-risk-averse group even when the productivity of the two types of workers are identical.

At the time the experiment was conducted, 1 USD = 7.3 SEK

F[3,126] = 0.596, p = 0.62 and F[3,126] = 1.75576, p = 0.16 for PCEm and PCEf respectively.

Risk seekers, recognizing that they have a greater propensity for risky choices than others, would regard risk seeking as a positive characteristic and would wish to consider that they possess this admirable characteristic to a greater degree than others and would thus increase the distance between themselves and others, while the opposite would be true for extremely risk-averse individuals.

Two separate regressions were performed, using a single dependent variable Own Certainty Equivalence (OCE) and Predicted Certainty Equivalence (PCE) in each. We found the magnitude of the coefficient estimates to be similar to the pooled model.

References

Bajtelsmit, Vickie, Alexandra Bernasek and Nancy A. Jianakoplos. (1999). “Gender Differences in Defined Contribution Pension Decisions,” Financial Services Reviews 8, 1–10.

Brinig, Margaret F. (1995). “Why Can’t a Woman be More Like a Man? Or Do Gender Differences Affect Choice?” In Rita J. Simon (ed), Neither Victim nor Enemy. University Press of America.

Brooks, Peter and Horst Zank. (2005). “Loss Averse Behavior,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 31(3), 301–325.

Brown, Roger. (1965). Social Psychology. New York: Free Press.

Byrnes, James, David C. Miller, and William D. Schafer. (1999). “Gender Differences in Risk Taking: A Meta-Analysis,” Psychological Bulletin 125, 367–383.

Carlsson, Fredrik, Dinky Daruvala, and Olof Johansson-Stenman. (2005). “Are People Inequality-Averse, or Just Risk-Averse?” Economica 72(287), 375–396.

Chakravarty, Sujoy, Glenn W. Harrison, Ernan E. Haruvy, and Elisabet E. Rutström. (2005). “Are You Risk Averse Over Other People’s Money?” Indian Institute of Management, unpublished manuscript.

Eckel, Catherine C. and Phillip J. Grossman. (2002a). “Forecasting Risk Attitudes: An Experimental Study of Actual and Forecast Risk Attitudes of Women and Men,” Department of Economics, Virginia Tech, unpublished manuscript.

Eckel, Catherine C. and Phillip J. Grossman. (2002b). “Sex Differences and Statistical Stereotyping in Attitudes Toward Financial Risk,” Evolution and Human Behavior 23(4), 281–295.

Hanoch, Yaniv, Joseph G. Johnson, and Andreas Wilke. (2006). “Domain Specificity in Experimental Measures and Participant Recruitment,” Psychological Science 17(4), 300–304.

Harrison, Glenn W. (1990). “Risk Attitudes in First-Price Auction Experiments: A Bayesian Analysis,” Review of Economics and Statistics 72, 541–546.

Hersch, Joni. (1996). “Smoking, Seat Belts, and Other Risky Consumer Decisions: Differences by Gender and Race,” Managerial and Decision Economics 17(5), 471–481.

Hersch, Joni. (1998). “Compensating Differentials for Gender-Specific Job Injury Risks,” The American Economic Review 88(3), 598–607.

Holt, Charles A. and Susan K. Laury. (2002). “Risk Aversion and Incentive Effects,” The American Economic Review 92(5), 1644–1655.

Hsee, Christopher K. and Elke U. Weber. (1997). “A Fundamental Prediction Error: Self-Others Discrepancies in Risk Preference,” Journal of Experimental Psychology 126, 45–53.

Hsee, Christopher K. and Elke U. Weber. (1998). “Cross-Cultural Differences in Risk Preferences by Cross-Cultural Similarities in Attitudes Toward Risk,” Management Science 44, 107–121.

Hsee, Christopher K. and Elke U. Weber. (1999). “Cross-Cultural Differences in Risk Preference and Lay Predictions,” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 12, 165–179.

Isaac, R. Mark and Duncan James. (2000). “Just Who Are You Calling Risk-Averse?” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 20(2), 177–187.

Jianakoplos, Nancy A. and Alexandra Bernasek. (1998). “Are Women More Risk Averse?” Economic Inquiry 36, 620–630.

Johnson, Johnnie E. and Phillip L. Powell. (1994). “Decision Making, Risk and Gender: Are Managers Different?” British Journal of Management 5, 123–138.

Kachelmeier, Steven J. and Mohamed Shehata. (1992). “Examining Risk Preferences Under High Monetary Incentives: Experimental Evidence from the People’s Republic of China,” The American Economic Review 82(5), 1120–1140.

Kristiansen, Connie M. (1990). “The Role of Values in the Relation Between Gender and Health Behaviour,” Social Behaviour 5, 127–133.

Kruse, Jamie B. and Mark A. Thompson. (2001). “A Comparison of Salient Rewards in Experiments: Money and Class Points,” Economics Letters 74(1), 113–117.

Kruse, Jamie B. and Mark A. Thompson. (2003). “Valuing Low Probability Risk: Survey and Experimental Evidence,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 50, 495–505.

Levin, Irvin P., Mary A. Snyder and Daniel P. Chapman. (1988). “The Interaction of Experiential and Situational Factors and Gender in a Simulated Risky Decision-Making Task,” The Journal of Psychology 122, 173–181.

Levy, Haim, Efrat Elron, and Allon Cohen. (1999). “Gender Differences in Risk Taking and Investment Behavior: An Experimental Analysis,” The Hebrew University, unpublished manuscript.

Loewenstein, George F., Elke U. Weber, Christopher K. Hsee, and Ned Welch. (2001). “Risk as Feelings,” Psychological Bulletin 127(2), 267–286.

Pålsson, Anne-Marie. (1996). “Does the Degree of Relative Risk Aversion Vary with Household Characteristics?” Journal of Economic Psychology 17, 771–787.

Powell, Melanie and David Ansic. (1997). “Gender Differences in Risk Behaviour in Financial Decision-Making: An Experimental Analysis”, Journal of Economic Psychology 18, 605–628.

Ross, Lee, David Greene, and Pamela House. (1977). “The ‘False Consensus Effect’: An Egocentric Bias in Social Perception and Attribution Processes,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 13, 279–301.

Saha, Somnath, Glen D. Stettin, and Rita F. Redberg. (1999). “Gender and Willingness to Undergo Invasive Cardiac Procedures,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 14, 122–125.

Schecter, Alison D., Pascal J. Goldschmidt-Clermont, Glenda McKee, Donna Hoffeld, Mary Myers, Roseann Velez, Julieta Duran, Steven P. Schulman, Nisha G. Chandra, and Daniel E. Ford. (1996). “Influence of Gender, Race, and Education on Patient Preferences and Receipt of Cardiac Catheterizations Among Coronary Care Unit Patients,” American Journal of Cardiology 78(9), 996–1001.

Schmidt, Ulrich and Stefan Traub. (2002). “An Experimental Test of Loss Aversion,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 25(3), 233–249.

Schulman, Kevin A., Jesse A. Berlin, William Harless, Jon F. Kerner, Shyrl Sistrunk, Bernard J. Gersh, Ross Dube, Christopher K. Taleghani, Jennifer E. Burke, Sankey Williams, John M. Eisenberg, Jose Escarce, and William Ayers. (1999). “The Effects of Race and Sex on Physicians’ Recommendations for Cardiac Catheterization,” The New England Journal of Medicine 340, 618–626.

Shapira, Zur. (1995). Risk Taking: A Managerial Perspective. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Schubert, Renate, Martin Brown, Matthias Gysler, and Hans W. Brachinger. (1999). “Financial Decision-Making: Are Women Really More Risk Averse?” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 89, 381–385.

Siegrist, Michael, George Cvetkovich, and Heinz Gutscher. (2002). “Risk Preference Predictions and Gender Stereotypes,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 87, 91–102.

Sunden, Annika E. and Brian J. Surette. (1998). “Gender Differences in the Allocation of Assets in Retirement Savings Plans,” American Economic Review 88(2), 207–211.

Svenson, Ola. (1978). “Risks of Road Transportation in a Psychological Perspective,” Accident Analysis and Prevention 10, 267–280.

Swanson, Janice M., Suzanne L. Dibble, and Karen Trocki. (1995). “A Description of the Gender Differences in Risk Behaviors in Young-Adults with Genital Herpes,” Public Health Nursing 12, 99–108.

Säve-Söderbergh, Jenny. (2003). “Pension Wealth: Gender, Risk and Portfolio Choices,” Swedish Institute for Social Research, Ph.D. dissertation.

Tobin, Jonathan N., Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller, John P. Wexler, Richard M. Steingart, Nancy Budner, Lloyd Lense, and Joseph Wachspress. (1987). “Sex Bias in Considering Coronary Bypass Surgery,” Annals of Internal Medicine 107, 19–25.

Vesterlund, Lise. (1997). “The Effects of Risk Aversion on Job Matching: Can Differences in Risk Aversion Explain the Wage Gap?” Iowa State University, unpublished manuscript.

Wang, Penelope. (1994). “Brokers Still Treat Men Better Than Women,” Money 23, 108–110.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my gratitude to the anonymous referee and to the editor for their many constructive comments. Many thanks also to Fredrik Carlsson, Olof Johansson-Stenman, Henrik Jaldell, Peter Frykblom and Effy Crawford for their comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

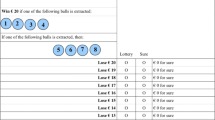

Table 4

Table 5

Table 6

Table 7

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Daruvala, D. Gender, risk and stereotypes. J Risk Uncertainty 35, 265–283 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9024-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9024-7