Abstract

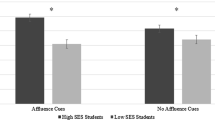

The match between a student’s academic ability and the academic ability of the student’s peers has been found to exert influence on student educational aspirations. Research on this has garnered mixed results with some finding that students whose peers have higher ability are more likely to develop a poor self-concept and lower their academic aspirations and others finding the opposite, that more able peer increase motivation and aspirations overall. While the effects of peer and student ability match on the educational aspirations of elementary and secondary students have received attention in recent years, these effects have largely been neglected in postsecondary education. In this study, I use recent postsecondary student data to see how the difference between the student’s SAT score and the mean institutional SAT affects the likelihood of the student experiencing a decrease in educational aspirations post college entry. Findings indicate that students whose scores are below the mean institutional SAT and who are attending less selective institutions are more likely to experience a decrease in future educational aspirations post college entry than students whose SAT scores are above the mean. However, students attending more selective institutions are protected from this effect, likely because of greater selection in admissions at more selective postsecondary institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The relationship between the effects of peer ability and student ability on student academic confidence and performance has been found at the elementary (see for example Hanushek et al. 2003; Hoxby 2000), middle (see for example Burke and Sass 2006), and high school level (see for example Ream and Rumberger 2008).

Children of alumni make up 10–25 % of the student body at selective institutions. At institutions that explicitly do not give preference to children of alumni that number is 2 % (Kahlenberg 2010).

“African-American applicants receive the equivalent of 230 extra SAT points (on a 1600-point scale), and being Hispanic is worth an additional 185 SAT points. Other things equal, recruited athletes gain an admission bonus worth 200 points, while the preference for legacy candidates is worth 160 points” (Espenshade and Chung 2005, p. 293). According to Espenshade and Chung (2005), there is evidence that students whose SAT score is above 1500 (pre-2006 scale) are also given some preference in that they are able to get in with lower high school grades.

Studies have cited that increasing diversity in learning environment leads to positive outcomes for all students such as being more aware of global and social issues. A diverse learning environment also has a positive effect on minority student achievement and retention (Hurtado and Guillermo-Wann 2013).

Affirmative action in postsecondary education has faced legal scrutiny and has been discontinued in several states: California (1996), Washington (1998), Michigan (2003, affirmative action was not discontinued but a predetermined amount of points cannot be awarded to applicants due to their minority status), Nebraska (2008), Arizona (2010), New Hampshire (2012), and Oklahoma (2012). The fact that affirmative action was discontinued in California and Washington prior to the sampling for the student data used in this study is not a concern as the data is nationally representative and there is evidence of racial preference in admission in all college selectivity tiers.

Hoxy and Weingarth (2005) suggest a similar mechanism, which they name the bad apple/shining light, where one very strong or very poor student can have an effect on the larger group if he exerts influence that is valued by the group. .

Grouping institutions into quartiles explains 85 % of the variation in institutional mean SAT for the postsecondary institutions included. Within quartiles, institutions have considerably similar mean institutional SAT scores, making this kind of categorization an acceptable way of indirectly controlling for institutional mean SAT.

There are additional tests (Advanced Placement (AP) test or SAT Subject Tests) that are standardized and administered nationally but are not mandatory for college applications. Furthermore, these tests are content specific and students choose what subject they want to be tested in. Also, as mentioned above, the ACT is becoming more widely used and has in 2013 caught up to the SAT so that now roughly 51 % of graduating high school students are taking the ACT and 51 % of graduating high school students are taking the SAT. This is likely because Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, Kentucky, Tennessee, Wyoming have made ACT testing of high school students mandatory (ACT 2013).

High school grades and SAT scores have a strong (r = 0.49, BPS:96/01) positive correlation. While both play an important part in college admissions, high school grades are numerically not comparable across admitted students within a postsecondary institution. Students apply from a wide variety of high schools with disparate course offerings and academic standards that result in numerically similar grade point averages conveying drastically different information about a student’s ability and preparation (Jencks and Phillips 1998). In the context of college admissions, high school grades are evaluated as a measure of the extent to which students took advantage and excelled within the bounds of the schooling environment they were placed in (Alon and Tienda 2007).

I am aware of two studies that make use of both high school record and SAT scores to determine the extent to which student’s academic credentials match the school’s academic credentials: Roderick et al. (2011), Smith et al. (2013). This method requires rich high school transcript data not available in the dataset used for this study.

An exception to this is Sacerdotes’ (2001) study of Dartmouth students and the affects of having a certain type of roommate on students own behavior.

References

ACT. (2013). Overview. Accessed July 25 2013. <http://www.act.org/products/k-12-act-test/>.

Alon, S., & Tienda, M. (2005). Assessing the mismatch hypothesis: Differences in college graduation rates by institutional selectivity. Sociology of Education, 78, 294–315.

Alon, S., & Tienda, M. (2007). Diversity, opportunity, and the shifting meritocracy in higher education. American Sociological Review, 72, 487–511.

Arcidiacono, P. (2004). Ability sorting and the returns to college major. Journal of Econometrics, 121(1–2), 343–375.

Arcidiacono, P. & Aucejo, E. & Hotz, V.J. (2013). University Differences in the Graduation of Minorities in STEM Fields: Evidence from California, IZA Discussion Papers 7227, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Astin, Alexander W. (1977). Four critical years. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Becker, S. O., & Ichino, A. (2002). Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. Stata Journal, StataCorp LP, 2(4), 358–377.

Black, D. A., & Smith, J. A. (2005). How robust is the evidence on the effects of college quality? Evidence from matching. Journal of Econometrics, Elsevier, 121(1–2), 99–124.

Bowen, W., & Bok, D. (1998). The Shape of the River: Long-term consequences of considering race in college and university admissions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Burke, M. A. & Sass, T. (2006). Classroom peer effects and student achievement, Working Papers 08-5, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Campbell, Richard T. (1983). Status attainment research: end of the beginning or beginning of the end? Sociology of Education, 56, 47–62.

Cohen, E. G. (1994). Restructuring the classroom: Conditions for productive small groups. Review of Educational Research, 64, 1–36.

College Board. (2013a). “Compare Scores.” Accessed on January 15, 2013. Available at: http://professionals.collegeboard.com/testing/sat-reasoning/scores/compare.

College Board. (2013b). “Applying 101.” Accessed on Mar 25 2013. Available at: http://bigfuture.collegeboard.org/get-in/applying.

Cole, S., & Barber, E. (2003). Increasing faculty diversity: The occupational choices of high achieving minority students. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Curtin, R., Presser, S., & Singer, E. (2005). Changes in telephone survey nonresponse over the past quarter century. Public Opinion Quarterly, 69, 87–98.

Davis, D. (1966). The campus as a frog pond: an application of the theory of relative deprivation to career decisions of college men. American Journal of Sociology, 72(I), 17–31.

Dale, S. B., & Krueger, A. B. (2002). Estimating the payoff to attending a more selective college: An application of selection on observables and unobservables. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 1491–1528.

Duran, Bernardine, & Weffer, Rafael E. (1992). Immigrants’ aspirations, high school process, and academic outcomes. American Educational Research Journal, 29, 163–181.

Espenshade, T., & Chung, C. Y. (2005). The opportunity cost of admission preferences at Elite Universities. Social Science Quarterly, 86(2), 293–305.

Gottfredson, L. S. (1981). Circumscription and compromise: A developmental theory of occupational aspirations. Journal of Counseling Psychology (Monograph), 28(6), 545–579.

Griffith, Amanda. (2009). Essays in Higher Education Economics. Cornell University Economics Department Dissertation.

Gurin, P., Dey, E. L., Hurtado, S., & Gurin, G. (2002). Diversity and higher education: Theory and impact on educational outcomes. Harvard Educational Review, 72(3), 330–366.

Gurin, P., & Epps, E. G. (1975). Black consciousness, identity and achievement: A study of students in historically black colleges. New York: Wiley Press.

Hanushek, Eric A., Kain, John F., Markman, Jacob M., & Rivkin, Steven G. (2003). Does peer ability affect student achievement? Journal of Applied Econometrics, 18, 527–544.

Harris, D. N. (2010). How do school peers influence student educational outcomes? Theory and evidence from economics and other social sciences. Teachers College Record, 112(4), 1163–1197.

Heath, Tamela. (1992). Predicting the educational aspirations and graduate plans of black and white college and university students: When do dreams become realities? Presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, Minneapolis, MN.

Hoxby, C. M., (2000). Peer effects in the classroom: Learning from gender and race variation. NBER Working Paper #7867. Cambridge, MA: NBER.

Hoxby, C. M., & Weingarth, G. (2005). Taking race out of the equation: School reassignment and the structure of peer effects. working paper.

Hurtado, S., & Guillermo-Wann, C. (2013). Diverse learning environments: Assessing and creating conditions for student success. Final Report to the Ford Foundation. University of California, Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute. Available at: <http://heri.ucla.edu/dle/DiverseLearningEnvironments.pdf>.

Jencks C, Mayer S. (1990). The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. In Inner-City Poverty in the United States, ed. L Lynn, Jr., MGH McGeary, pp. 111–85. Washington, DC: Natl. Acad. Press.

Jencks, Christopher, & Phillips, Meredith (Eds.). (1998). The black-white test score gap. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Kahlenberg, R. (Ed.). (2010). Affirmative action for the rich: Legacy preferences in college admissions. New York: Century Foundation.

Kao, G. (1995). Asian-Americans as model minorities? A look at their academic performance. American Journal of Education, 103, 121–159.

Karen, D. (2002). Changes in access to higher education in the United States: 1980–1992. Sociology of Education, 75, 191–210.

Light, A., & Strayer, W. (2000). The determinants of college completion: school quality or student ability? Journal of Human Resources, 35, 299–332.

Long, Mark. (2008). College quality and early adult outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 27(5), 588–602.

Loury, L. D., & Garman, D. (1995). College selectivity and earnings. Journal of Labor Economics, 13(2), 289–308.

Marsh, H. W. (2007). Self-concept theory, measurement and research into practice: The role of self-concept in educational psychology. Leicester: British Psychological Society.

Marsh, H. W., & Hau, K. T. (2003). Big-fish-little-pond effect on academic self-concept: A cross-cultural (26 country) test of the negative effects of academically selective schools. American Psychologist, 58, 364–376.

Melguizo, T. (2008). Quality matters: Assessing the impact of selective institutions on minority college completion rates. Research in Higher Education, 49(3), 214–236.

Naemi, B., Burrus, J., Kyllonen, P., & Roberts, R. (2012). Building a case to develop noncognitive assessment products and services targeting workforce readiness. Princeton: ETS.

Ogbu, J. U. (2003). Black American students in an affluent suburb: A study of academic disengagement. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Pascarella, Ernest T. (1985). College environmental influences on learning and cognitive development: A critical review and analysis. Pp. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. Volume 1, edited by John C. Smart. New York: Agathon.

Pascarella, E., & Terenzini, P. (2005). How college affects students. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Inc.

Ream, R. K., & Rumberger, R. (2008). Student engagement, peer social capital, and school dropout among Mexican American and Non-Latino white students. Sociology of Education, 81, 109–139.

Roderick, M., Coca, V., & Nagaoka, J. (2011). Potholes on the road to college. Sociology of Education, 84(3), 178–211.

Rosenbaum, P., & Rubin, D. B. (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70, 41–55.

Sewell, William H., Haller, A. O., & Portes, A. (1969). The educational and early occupational attainment process. American Sociological Review, 34(February), 82–92.

Sacerdote, B. (2001) Peer effects with random assignment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, CXVI, 681–704.

Shavit, Y., Arum, R., Gamoran, A., & Menahem, G. (Eds.). (2007). Stratification in higher education: A comparative study. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Smith, J., Pender, M., & Howell, J. S. (2013). The full extent of student-college academic undermatch. Economics of Education Review, 32, 247–261.

Thistlethwaite, Donald L., & Wheeler, Norman. (1966). Effects of teacher and peer subcultures upon student aspirations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 57, 35–47.

Tsui, Lisa. (1995). Boosting female ambition: How college diversity impacts graduate degree aspirations of women. Presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, Orlando, FL.

Webb, N., & Farivar, S. (1999). Developing productive group interaction in middle school mathematics. In A. M. O’Donnell & A. King (Eds.), Cognitive perspectives on peer learning (pp. 117–149). Mahwah: Lawrence, Erlbaum Associates.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jagešić, S. Student-Peer Ability Match and Declining Educational Aspirations in College. Res High Educ 56, 673–692 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-015-9366-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-015-9366-y