Abstract

Honors colleges housed in public universities began only in the last half century, but have become nearly ubiquitous over the last 20 years. This paper, using recent data from the oldest stand-alone honors college in the country, is the first to study how the application and enrollment decisions of honors college students differ from the general population of students considering a large public university. Overall, the empirical results suggest that honors college applicants and enrollees are drawn from the right-tail of its host institution’s ability distribution, independent of residency status. Nonetheless, honors-college applicants are still more likely to enroll in selective and liberal arts institutions than the general pool of admits to a large public university, which is only partially offset by the effect of honors-college admission. It follows that honors colleges enroll academically stronger, but not the strongest, admits to a large public university.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Long (2002) finds that nearly all honors colleges are located in institutions classified as “Highly Competitive”, “Very Competitive”, or “Competitive” and that, similar to CHC, most have a separate, selective admissions process, offer special living arrangements (i.e., separate dorm or wing of a dorm), have special forms of financial aid, and make up approximately 5% of the student population.

In July 1975, the college was named Robert D. Clark Honors College to honor the vision and dedication of a UO speech professor who led the founding of the Honors College.

The admittance rate for the general population of UO applicants is 90% with an enrollment rate of 34%.

The resource fee in 2009 was a $1000 per term in the first year and slightly lower amount for each term after the first year until graduation.

The student scoring sheet data from the CHC include all applicants from 2009 and all enrollees during the three academic years. Unfortunately, two boxes of alphabetically listed applicant files were inadvertently discarded by the CHC. Thus, data for 2007 include only applicants who were denied by the CHC and whose last names begin with L to Z; whereas the 2008 data include only applicants who declined the admission offer and whose last name initials A to M. We demonstrate subsequently in Table 3 columns 1 and 2 that the alphabetically generated missing data are not systematic in nature. In fact the estimates that rely exclusively on the 2009 data are qualitatively equivalent to those that include the full three years. Thus, we use all three years of data that increase the statistical power of our estimates and generally focus on the sign and not the magnitude of the coefficients. These data limitations only apply to the applicant analysis in Table 3 that rely on the student scoring sheets in addition to other UO data sources that do not have missing data.

The total admission score possible was 30 in 2007 and became 28 in 2008 and 2009.

The inclusion of fix effects in the logit model can significantly reduce the sample size because there are 0.6% of resident students and 8% of non-resident students that are the only applicant from a particular high school. To test the sensitivity of the results to the distributional assumption of the dependent variable (i.e., OLS versus logit) and the presence of fixed effects, OLS and logit models are estimated without fixed effects and compared to the presented OLS specification with fixed effects. In general, the qualitative conclusions are robust across these three alternative specifications for the significant explanatory variables.

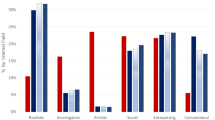

Descriptive statistics (available upon request) show that, whereas the admissions rate into the UO is approximately 90%, only 62 (50)% of in-state (out-of-state) CHC applicants are admitted to the honors college even with their stronger academic background. On the other hand, approximately 38 (16)% of CHC applicants enroll, which is lower than that of the UO that is 54 (21)% for in-state (out-of-state) students.

Separate estimates of the admissions model by residency status yield very similar findings as those for the full population. However, the coefficients on the SAT scores and high-school GPA are not significant for out-of-state students. This suggests that the CHC follows their formal admissions guideline more carefully for non-resident students than for their in-state counterparts.

Similar to these findings, enrollment estimates in Curs and Singell (2002) that use all UO applicants finds that the institution tends to lose the best students to competing institutions.

For UO applicants who do not apply to the CHC, approximately 8 and 7% respectively enroll in selective and top-100 liberal arts institutions as defined by the 2009 U.S. and World Report, and 15 and 7% respectively enroll in 4-year publics in the West and other 4-year publics. Descriptive statistics (not presented) show UO admits who choose to enroll in selective or top-100 liberal arts institutions have higher average SAT scores and high school GPA than those who choose to enroll UO and other 4-year public institutions.

References

Brewer, D. J., Eide, E. R., & Ehrenberg, R. G. (1999). Does it pay to attend an elite private college? Cross-cohort evidence on the effects of college type on earnings. Journal of Human Resources, 34(1), 104–123. Winter.

Carrell, S. E., Fullerton, R. L., & West, J. E. (2009). Does your cohort matter? Measuring peer effects in college achievement. Journal of Labor Economics, 27(3), 439–464.

Cosgrove, J. (2004). The impact of honors programs on undergraduate academic performance, retention, and graduation. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal/137

Curs, B., & Singell, L. D, Jr. (2002). An analysis of the application and enrollment processes for in-state and out-of-state students at a large public university. Economics of Education Review, 21, 111–124.

Dale, S. B., & Alan B. K. (2002), Estimating the payoff to attending a more selective college: An application of selection on observables and unobservables. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1491–1527.

Dynarski, S. (2000). Hope for whom? Financial aid for the middle class and its impact on college attendance. National Tax Journal, 53(3), 629–662.

Ehrenberg, R. G. (2002). Tuition rising: Why college costs so much. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Heller, D. E. (2008). Institutional and state merit aid: Implications for students. University of Southern California, Memo.

Hoxby, C. (1997). How The changing market structure of us higher education explains college tuition. NBER working paper No. 6323.

Hoxby, C. (1998). The return to attending a more selective college: 1960 to the present. Harvard University, Mimeo.

Long, B. T. (2002). Attracting the best: The use of honors programs to compete for students (pp. 1–27). Chicago, IL: Spencer Foundation (ERIC Reproduction Service No. ED465355).

McPherson, M. S., & Schapiro, M. (1994). Merit aid: Students, institutions, and society. Consortium for Policy Research in Education Research Report, No. 30, August.

Monks, J., & Ehrenberg, R. G. (1999). U.S. news & world report’s college rankings: Why do they matter? Change, 31(6), 43–51.

Peterson’s. (2005). Honor programs & colleges (p. 427, 4th ed.). ISBN: 978-0768921410.

Rinn, A. N. (2005). Trends among honors college students: An analysis by year in school. The Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 16(4), 157–167.

Rothschild, M., & White L. J. (1993). The University in the marketplace: Some insights and some puzzles. In C. Clotfelter & M. Rothschild (Eds.), Studies of supply and demand in higher education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sacerdote, B. (2001). Peer effects with random assignment: Results for dartmouth roommates. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2), 681–704.

Samuels, S. H. (2001). How do a get a private-college education for the price of a public with Honors. New York Times.

Sederberg, P. C. (2008). Introduction. In C. Sederberg Peter (Ed.), The honors college phenomenon. NCHC monographs series. Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press.

Seifert, T. A., Pascarella, E. T., & Colangelo, N. (2007). The effects of honors program participation on experiences of good practices and learning outcomes. Journal of College Student Development, 48(1), 57–74.

Singell, L. D. (2004). Come and stay a while: Does financial aid effect enrollment and retention at a large public university? Economics of Education Review, 23(5), 459–472.

Singell, L., Waddell, G., & Curs, B. (2006). Hope for the pell? The impact of merit-aid on needy students. Southern Economic Journal, 73(1), 79–99.

Sperber, M. (2000). End the mediocrity of our public universities. Chronicle of Higher Education.

St. John, E. P. (2003). Refinancing the college dream: Access, equal opportunity, and justice for taxpayers. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Winston, G. C. (2003). Subsidies, hierarchy and peers: The awkward economics of higher education. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(1), 13–36. Winter.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dean David Frank and Paula Braswell of the Robert D. Clark Honors College at the University of Oregon for providing the data that were essential to our research. We are responsible for any remaining errors and omissions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singell, L.D., Tang, HH. The Pursuit of Excellence: An Analysis of the Honors College Application and Enrollment Decision for a Large Public University. Res High Educ 53, 717–737 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-012-9255-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-012-9255-6