Abstract

The growing focus on the blue economy is accelerating industrial fishing in many parts of the world. This intensification is affecting the livelihoods of small-scale fishers, processors, and traders by depleting local fishery resources, damaging fishing gears, putting fishers' lives at risk, and compromising market systems and value chain positions. In this article, we outline the experiences, perspectives, and narratives of the small-scale fishing actors in Ghana. Drawing on qualitative interview data, we examine the relationship between small-scale and industrial fisheries in Ghana using political ecology and sustainable livelihood approaches. We demonstrate how industrialised, capital-intensive fishing has disrupted the economic and social organisation of local fishing communities, affecting incomes, causing conflicts, social exclusion and disconnection, and compromising the social identity of women. These cumulative impacts and disruptions in Ghana's coastal communities have threatened the viability of small-scale fisheries, yet coastal fishing actors have few capabilities to adapt. We conclude by supporting recommendations to reduce the number and capacity of industrial vessels, strictly enforce spatial regulations, and ensure "blue justice" against marginalisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Small-scale fisheries account for around 40% of global fish catch and support over 113 million fishery workers along the value chain globally, with at least 45 million women involved (IHH 2021; Teh and Sumaila 2013). In developing countries, small-scale fisheries are also critical components of the domestic fishery chains and economies of coastal communities, supporting livelihoods, nutrition needs, and social well-being (Schorr 2005). Moreover, small-scale fisheries' contributions transcend their economic values to encompass social, relational, and historical networks (IHH 2021; O'Neill and Crona 2017).

Globally, the expansion of large-scale ocean fisheries has significantly impacted small-scale fisheries by achieving unprecedented levels of overfishing and overproduction (Longo et al. 2011; Mansfield 2010). Despite initiatives to reduce overfishing, over the last few decades in many locations, governments, international organisations, and multilateral institutions have promoted the industrialisation of the fisheries sector in the pursuit of economic progress and modernisation (Mansfield 2010; Overå, 2011). Scholars have documented the unequal relations between developed and developing countries in terms of technological advancement and investment in industrial fishing because of the global south's limited resources (Belhabib et al. 2015; Okafor-Yarwood and Belhabib 2020). They have also highlighted the imbalance in subsidy allocation between large- and small-scale fisheries, with most of the harmful subsidies going to industrial fishing businesses (Schuhbauer et al. 2020; Sumaila et al. 2019, 2016). For example, the role of fisheries subsidies in the success of Chinese distant trawler fleets in developing countries in Africa and Asia is a global concern for fisheries management (Belhabib et al. 2015; Mallory 2016). According to Mallory (2016), China spent over $6.5 billion on fisheries subsidies in 2013, 95 percent of which were harmful to sustainability. These subsidies, of which 94% are fuel subsidies, are linked to unsustainable fishing practices in developing countries, including overfishing, overcapacity, and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing (Mallory 2016).

Recent studies have underscored the contribution of the global fisheries industry to climate change through large fuel consumption and have emphasised the substantial effects of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems (Sala et al. 2022; Wang and Wang 2022; Sumaila et al. 2011; Ficke et al. 2007). Recent estimates indicate that worldwide fishing industry emissions increased by 28% in total between 1990 and 2011 and that fisheries produced 179 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent Greenhouse gases (4% of global food production) (Parker et al. 2018). The growth in global fisheries emissions is mostly attributable to increased harvests by fuel-intensive industrial fisheries activities, which depend heavily on fossil fuels for fishing, searching for fish (trawling), and handling, including refrigeration and industrial processing (Sala et al. 2022; Parker et al. 2018). Small-scale fisheries also contribute to the global fisheries' fossil fuel consumption, which comprises mostly of travel to and from fishing grounds. However, most of their passive fishing gear is set and hauled manually or with small motor power, making them one of the world's most efficient forms of animal protein production (Parker and Tyedmers 2014).

In addition, the expansion of industrial bottom trawling activities by industrial fishing vessels has considerably contributed to the loss of ocean biodiversity (Kuczenski et al. 2022; McConnaughey et al. 2020). A recent assessment by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (2022), for example, highlights that in marine systems, industrial fishing has had the most impact on biodiversity in the past 50 years through overexploitation. Industrial fishing corporations cover at least 55 percent of the oceans, concentrated in the north-east Atlantic, north-west Pacific, and upwelling zones off the coasts of South America and West Africa (IPBES, 2022). In many developing countries, these trends in global fisheries have created significant social and economic legacies for small-scale fisheries, marine ecosystems, and food security (Kolding and van Zwieten 2011; Pauly et al. 2005).

The literature on the "tragedy of the commons" (Hardin 1998) has frequently been referenced to explain over-exploitation of fisheries, with less emphasis on the influence of industrialisation (Feeny et al. 1996; McWhinnie 2009). Yet technical advancements in the fisheries sector have accelerated resource depletion, particularly since the second half of the twentieth century (Campling and Colás, 2021). Some researchers contend that fisheries resource exploitation has been intensified by the global industrial revolution facilitated by capital-intensive fishing and private capital accumulation (Berkes et al. 2006; Longo and Clausen 2011; Mansfield 2010). Industrialisation and technology have accelerated the expansion and exploitation of marine fisheries in many developing countries beyond their management capability (Berkes et al. 2006; Eriksson et al. 2015). These global patterns of marine resource exploitation have been described as "contagious resource exploitation" (Eriksson et al. 2015, p. 435), a "tragedy of the commodity" (Longo and Clausen 2011, p.316) and profit-driven "roving banditry" (Berkes et al. 2006, p.1557). We build on this critical lens to demonstrate how the industrial fishing transitions in Ghana have negatively affected small-scale coastal fishing livelihoods.

Recent global and regional initiatives to define Africa's oceans and coastal frontiers as a "blue economy" have intensified (African Union, 2019; Economic Commission for Africa, 2016; European Investment Bank 2021). While stakeholders use the term blue economy in very different ways (Silver et al. 2015; Smith-Godfrey 2016) and the types of implementation vary, the concept aligns closely with green economy paradigms that aim to stimulate economic growth through the maritime economy while safeguarding ecological sustainability and fostering social inclusion (Bennett et al. 2019; Smith-Godfrey 2016). Numerous African nations, including Seychelles, Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, and South Africa, are exploring blue economy initiatives (Bolaky 2020). Expanding industrial fishing is a major component of Ghana's blue economy. In particular, the National Policy for the Management of Marine Fisheries Sector 2015–2019 is framed to create employment, contribute to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and generate foreign exchange revenue through fisheries (Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development (MoFAD, 2015, p.1). We draw on this framing to argue that industrial fishing seems likely to intensify and expand in Ghana. Recent developments, such as offshore petroleum exploration and temporary closed-season fishing restrictions, have put coastal fisheries in Ghana under some threat (Adjei and Overå, 2019; Owusu and Andriesse 2020). In addition, unlike other sectors of the blue economy in Ghana, industrial fishing directly competes with small-scale fishing for coastal fisheries resources, degrading fisher communities' sustainable livelihoods and resilience systems (Nolan 2019; Seto 2017). While acknowledging small-scale fishers' human agency and capacity for adaptation, such measures are limited to coping actions (Freduah et al. 2018) and do not address the fundamental impact of industrial fishing in Ghana.

In most developing countries, fishery problems have deep historical, cultural, and political roots (Bavinck 2005; Okeke-Ogbuafor et al. 2020). In this study of fisheries livelihoods, we used a qualitative approach to draw on the experiences, views, and narratives of small-scale actors who are usually excluded from fisheries management (Martins et al. 2018). We discuss the impacts of industrial fishing on small-scale livelihoods, emphasising the need for inclusion and protection of small-scale fishing in Ghana's aspirations for the blue economy. Our paper broadly contributes to the growing blue justice literature aimed at safeguarding small-scale fisheries globally.

Methods and materials

Ghana's industrial fishing transformation

After beginning in the 1950s as part of a state-led development reform strategy to maximise catch of Ghana's then enormous fish stocks and as an economic strategy to modernise and diversify the economy, the industrialisation of the country's fisheries expanded by the early 2000s to incorporate joint ventures and lease finance agreements (Akpalu and Eggert 2021; Bank of Ghana 2008; Nunoo et al. 2014). According to reconstructed data from the Sea Around Us Initiative, Ghanaian fisheries had much higher catches per unit of effort in the 1950s compared to more recent decades, despite low productivity (see Pauly and Zeller, 2015 for full methods and data description). In 1952, the Colonial Fisheries Department imported two 30-foot motorised boats from the United Kingdom for testing purposes, which proved effective and led to the establishment of a local boatyard production corporation (Acquay 1992; Akyeampong 2007). In the 1960s, Ghana's first president, Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah, established the State Fishing Corporation (SFC), acquired state trawler fishing vessels, and constructed cold storage facilities, including the expansion of the Tema Harbour (Bennett and Bannerman 2002; Overå, 2011). By the 1970s, the SFC fleet had grown to 34 vessels operating in Ghana and neighbouring nations. However, with ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1982, these vessels were repatriated to Ghana's limited continental shelf, increasing strain on its maritime waters (Akpalu and Eggert 2021; Atta-Mills et al. 2004). The SFC subsequently collapsed due to Ghana's economic challenges, political instability, and technical and managerial difficulties (Bank of Ghana 2008; Nunoo et al. 2014).

A fisheries law (Fisheries Decree, 1979) established the framework for joint ventures (JVs), allowing Ghanaians to control at least 50% of JV firms. This policy reform has been described as the first significant step towards expanding foreign private sector participation in industrial trawler fishing in the country (Acquay 1992). In the 1980s, in response to Ghana's economic decline, the government implemented a structural adjustment program (SAP) with the support of the World Bank (Acquay 1992; Bennett 2002). As part of the SAP, Ghana's currency was devalued, trade barriers were removed, inefficient state-owned enterprises were privatised, and the civil service was restructured. Acquay (1992) observed that the SAP had three broad implications for Ghana's maritime fisheries. First, the devaluation was an incentive for JV firms to expand and intensify their harvests and exports. In contrast, locally owned fishing firms, including the SFC, were forced to liquidate due to high overhead costs from imported fishing inputs and gear. Second, foreign direct investment increased, leading to the significant growth of JV industrial trawlers from Europe and Asia. Third, the Fishery Department's staff numbers were reduced and employment was restricted, affecting its capacity to research, manage, and enforce the reduction in excess fishing in Ghana.

A subsequent fisheries law (Fisheries Act 625, 2002) limited foreign capital in industrial fishing to tuna (Akpalu and Eggert 2021). The law also restricted industrial trawling to Ghanaians, the government, or a company or partnership wholly owned by Ghanaians, and it prohibited foreign beneficiary ownership. It also permitted lease-type financing agreements with foreign firms, such as hire-purchase, chartering, and rental of vessels and fishing gear. While these reforms sought to maximise local gains from Ghana's industrialisation and increase domestic economic growth through fisheries resources (Bennett 2002), local entrepreneurs resorted to leasing from Chinese companies due to the difficulty of raising domestic financing to run capital-intensive industrial trawlers. However, these lease-type commercial arrangements evolved into what has been labelled as an illegal strategy (EJF2018) used by distant-water fishing companies to control industrial trawler fishing (Belhabib et al. 2020, 2015), and by 2021, they were the only agreements permissible for trawler fishing in Ghana. For instance, Ghanaian entrepreneurs might obtain the licences while their Chinese partners provide finance and retain significant portions of the profit. In most instances, trawler captains and fishing company managers are Chinese, while Ghanaians serve as casual crew.

The proliferation of Chinese trawlers, which target most of the local catch, has resulted in these stocks' dramatic decline (EJF 2018; Failler and Binet 2011). A recent stock assessment by the Ghana Fisheries Commission shows increased fishing effort over the last decade, yet the fleet's catch per unit of effort has decreased except for the tuna fleet (MoFAD 2015). Local fishers began purchasing rejected fish from commercial trawlers in reaction to the reduction in catch rates (Nunoo et al. 2009). This increased demand for "trash fish" (locally called saiko) and bycatch resulted in a massive domestic market boom and encouraged transhipment involving local community entrepreneurs. Thus, the depletion of coastal fisheries in Ghana has primarily been due to licenced trawlers either operating in the artisanal fishing zone or employing illicit fishing gear and conducting illegal transhipments (Nunoo et al. 2014). Although the steady growth in the number of small-scale fishing canoes has also compounded the decline of coastal fisheries, this study examines the impacts of industrial fisheries on small-scale fishing chains.

The geographical range of operations for different fisheries types is divided into the Inshore Exclusive Zone and the Exclusive Economic Zone. In principle, Ghana's Inshore Exclusion Zone is reserved for small-scale fishing (Fisheries Act 625, 2002), but this is rarely the case in practice. Local Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) data indicates that all industrial trawler arrests in Ghana between 2007 and 2015 related to territorial violations (Friends of the Nation 2015). The small-scale fishing sector in Ghana consists of motorised and non-motorised canoes ranging in length from 3 to nearly 20 m (MoFAD 2015). Ghana has an open-access policy for small-scale fisheries, although the Fisheries Law (Act 625) stipulates that in order to fish, small-scale fishers must first register with their local district assembly. Approximately 200,000 fishers operate around 12,000 small-scale fisheries canoes in 334 fishing community landing centres in Ghana (Adjei and Overå, 2019). Small-scale fishers frequently employ beach seines, line, set nets, gillnets (locally called ali), and drift gill nets (Lazar 2018). Most of the small-scale catch is processed and marketed in domestic markets in the local and bigger cities, with a considerable amount also exported to neighbouring Togo, Benin, Cote d'Ivoire, and Nigeria (Ayilu 2016). However, the total catch volume of small pelagic catch targeted by the local small-scale fisheries has steadily declined over the years, putting local livelihoods under threat (Fig. 1). Fishers have adapted their livelihoods through both legal and illegal measures, such as internal and external migration (Bortei-Doku 1991; Overå, 2005), as well as fishing with explosives, poisons, aggregating devices, and monofilament nets (Freduah et al. 2018). Small-scale processors leverage smokeless ovens (Ahotor and FAO-Thiaroye Technique) to minimise processing losses resulting from burns to the fish and to improve fish quality for premium prices (Mindjimba et al. 2019; Seyram 2020).

Source: Lazar et al. (2018), reproduced with permission

Graph showing the average landings of small pelagic stocks (red line) and fishing effort (number of canoes) (blue bars) from 1990 to 2016.

Study areas

The study was conducted in two of Ghana's coastal regions, the Western Region and the Greater Accra Region (Fig. 2). These regions are the country's industrial and commercial centres, with considerable infrastructure, including Ghana's only two commercial ports and its two largest industrial fishing ports, Sekondi-Takoradi and Tema. Ghana's industrial vessel fleets are classified into three categories: the semi-industrial sector, the industrial sector (mostly comprised of trawlers), and industrial foreign tuna vessels. Together, these two regions have 15 of Ghana's 26 coastal administrative districts, with the total small-scale fisher population estimated at about 26,000 in the Greater Accra Region and 34,000 in the Western Region (Dovlo et al. 2016).

This study focuses on eight fishing communities that are important fishing towns for small pelagic catches in the two regions, with fish processing and trading being the primary occupations of most of the women residents. The key features of the study locations and districts are summarised in Table 1, and their locations in Fig. 2. Table 1 shows the number of small-scale fishing fleets and people who engage in fishing in the various localities, as well as the average catch quantities, underscoring the importance of small-scale fishing to the local economies. These communities were drawn from seven of the coastal administrative districts where small-scale fishing constitutes a significant economic activity, and they were purposively selected (Marshall and Rossman 2014) for one or all of the following reasons: (1) their proximity to the commercial fishing port where the industrial fishing vessels land and begin their fishing; (2) their contribution to small-scale fisheries catch; and (3) their listing as a community in Ghana's Fisheries Scientific Division's Marine Canoe Survey Framework of the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development (Dovlo et al. 2016). Ghana's Fisheries Scientific Division's Marine Canoe Survey indicate that the catch quantities in the communities vary based on a number of reasons, including the number of fishers, the variation in fishing capability in terms of fishing gears, and the seasonal fluctuations in the fishery across the coastal villages.

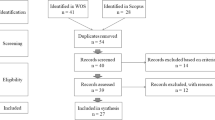

Data collection

Our data triangulation approach in this study included in-depth individual interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) (Jonsen and Jehn 2009). Field data were collected between January 2021 and June 2021, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic. The lead author participated in most field interviews using video conferencing software (Zoom.us).Footnote 1 During the data collection period, domestic restrictions were eased, and fishing recommenced in the local coastal communities. The interviews were conducted using a COVID-19 safe-research protocol checklist (McDougall et al. 2020) and Ghana Health Service (2021) COVID-19 health advice protocols.

In Ghanaian coastal communities, the chief fisherman and chief fish processor are the traditional custodians of fisheries and relate with external stakeholders on behalf of fishing actors (Ameyaw et al. 2021; Bennett and Bannerman 2002). These community leaders constituted the key informants for the in-depth interviews (n = 16) (i.e. two key informant interviews in each community). The FGDs (n = 2) in each community included one (n = 1) with five small-scale fishers and another one (n = 1) with five fish processors/traders. The participants who formed the FGDs (n = 16) were part of the governing council of the chief fisherman and the chief fish processor, and they were drawn from different landing beaches within the community. In total, we conducted 16 interviews and 16 FGDs were conducted, comprising 96 participants across the communities: Western Region (24 men, 24 women) and Greater Accra Region (24 men, 24 women). These participants had been involved in the local fisheries of the community for at least a decade and had extensive experience and history regarding local fisheries livelihoods. In Ghana, both men and women are actively involved in small-scale fisheries. However, the division of labour is sex-segregated; with few exceptions, males work as fishers and women work as processors/traders (Walker 2001). We purposively recruited both fishers (men) and processors/traders (women) to reflect this gendered division of labour in Ghana's small-scale fisheries value chain.

All informants verbally consented to participate in the study. The topics covered during the focus group discussions (FGDs) and individual key informant interviews (KEIs) included the effects of declining coastal fisheries on social cohesion and inclusion, community conflicts and disconnections, fish trading and processing, income level and the day-to-day livelihoods of fishing actors, as well as coastal cultural institutions, including traditions, norms and identity. The interviews lasted 30 to 60 min on average. Field interviews were conducted in Ga and Fante, two of the native languages spoken in the study communities. The fourth co-author is fluent in the Fante language and conducted those interviews. The Ga interviews were conducted with the assistance of an interpreter.

Data analysis

The interviews were recorded with permission, translated, and transcribed. The Fante interviews were translated verbatim into English by the fourth co-author and the Ga interviews were translated into English using an interpreter; both sets of interviews were then transcribed. We used thematic content analysis, which involved the reading, scrutinising, identifying themes, and threading up of themes from the transcripts. First, the transcribed interviews notes were read manually to identify key emerging trends. Second, the interview notes were imported into NVIVO 12 for coding and theme comparison for validity. The lead author initially coded the data, which was subsequently validated by the second co-author. We generated seven themes in total from the coding, which were then integrated and qualitatively analysed using the assets conceptualisation of the sustainable livelihoods framework (Allison and Ellis 2001; Scoones 2015). Additionally, direct quotations from selected participants are used where appropriate to provide a complete argument.

The theoretical framing for the data analysis draws from the sustainable livelihood framework and political ecology. Building on Sen's (1981) concepts of entitlements and capabilities, the sustainable livelihood framework focuses on various aspects of livelihoods, including the vulnerability context, asset portfolios, livelihood strategies, and institutions that mediate the ability to attain (or fail to attain) such outcomes (Chambers and Conway 1992; DfID 1999; Sen 1981). The framework outlines the assets and activities required by people and households to meet their livelihood needs and deal with pressures, disruptions, and perturbations (Scoones 2015). In particular, the sustainable livelihood framework examines the interrelationships of people's assets (human, financial, physical, natural, and social) and the pursuit of their livelihoods at the individual, household, or community level (Scoones 1998). This analytical approach has been extensively used to study various aspects of livelihoods, including vulnerability, impacts of shocks, and adaptive responses (Allison and Ellis 2001; Ferrol-Schulte et al. 2013). Livelihoods become vulnerable when the assets required for their social, economic, and ecological systems to adapt, adjust, and respond are weakened or eroded (Adger 2006).

In West Africa, fisheries development and management projects first adopted the sustainable livelihood framework to assess small-scale fisheries in the 1990s (Allison and Horemans 2006; DfID 1999). In the current study, we used the sustainable livelihood framework specifically to explain the impacts of marine industrial fishing on the livelihood assets of small-scale fishers (Bennett and Dearden 2014; Owusu and Andriesse 2020). As a result, the sustainable livelihood framework's existing five capital assets—human, financial, physical, natural, and social—have been reorganised as economic (including financial and physical), social, and natural assets. This reorganisation revealed how specific livelihood assets are related, which is particularly useful for assessing fishers' livelihood prospects and limitations.

The interview data reflects the interactions between small-scale and industrial fishers in Ghanaian fishing communities, with a focus on the livelihood assets most impacted by these interactions. By fishing with nets, canoes, and other fishing gear, as well as by fish processing and trading, these communities derive incomes principally from economic assets, both financial and physical. Their social assets include their culture, history, and social networks, which all revolve around everyday fishing. The ocean is a natural asset that which includes the fishers' knowledge of its ecology along with the value-chain players' competence and capabilities.

Despite the usefulness of the sustainable livelihood framework, it has been criticised for insufficiently incorporating the dynamics of power and historical patterns of change in mediating access to environmental resources (De Haan and Zoomers 2005). In our analysis, in addition to emphasising the importance of livelihood assets, we also use a political ecology approach that emphasises the importance of "scale, history, conflict and power relations" (Nolan 2019, p. 12), which influence resource access and the politics around fishers' livelihoods (Robbins 2011; Bryant 1992). Ghanaian industrial fishing emerged as a historical outcome, hence its growth into coastal areas represents a capitalist expansion and the failure of fisheries management underscores power imbalances (Nolan 2019; Mansfield 2010). In summary, we used the intersecting theoretical underpinnings of SLA and political ecology to explore how the expansion of industrial fishing in Ghana has interrupted and damaged not only the sustainable livelihood assets of coastal fisheries actors, but also their ability to respond effectively.

Limitations

The research focused on understanding the concerns of small-scale fisheries. However, the inability to interview industrial fishers due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the difficulty with access constitute a limitation. To address this gap, we reviewed existing literature and drew on the authors' experiences as fisheries researchers in developing countries, particularly the first author's Ghanaian experiences. While this research addresses issues raised in the literature and allegations made by the small-scale fishers and processors we interviewed, it does not seek to provide factual evidence of specific instances of wrongdoing.

Results and discussion

This section provides a qualitative explanation of the disruption to local fisheries actors' economic, social, cultural, natural, and human assets, as well as the reduction in their livelihoods and well-being caused by industrial-scale fishing activities. The results in this section constitute common themes based on the responses, comments, and experiences of the actors interviewed regarding the impacts of the industrial fishing.

Economic (financial and physical) assets

Income and livelihood

In Ghana, access to sufficient fish, in terms of both quality and quantity, is no longer a privilege reserved for local communities; it is now available to technologically advanced foreign commercial trawlers (Nolan 2019; Nunoo et al. 2014). The expansion of industrial trawlers' activities into local fishing grounds, mostly at night, has caused small-scale fishers to withdraw, allowing industrial trawlers to exploit and overfish the pelagic species. The industrial vessels use adapted fishing gear (for example, illegal small-mesh nets) to target these species in coastal protected areas. The number of industrial fishing vessels has increased in Ghana through massive Chinese investment (Akpalu & Eggert 2021; EJF 2018), a situation that has affected how, where, what, and for how long local fishers can actually catch. For instance, in Ghana's inshore exclusive zone, fishers participating in this study reported conflict with industrial and/or semi-industrial trawler vessels that led to the destruction of physical assets (canoes and fishing nets) and injuries to crew members. The local fishermen explained that losing fishing gear hampers their primary economic activity and source of income. In the coastal communities, the construction of a wooden canoe and the acquisition of an outboard motor and fishing nets represents a lifetime investment for local fishers. They acquire such equipment and gear primarily through the sale of personal property or by taking out small loans. They explained that when such investments are damaged, the consequence on family livelihoods becomes "hard". Moreover, the way fishers conduct their fishing trips in Ghana has also changed due to the increased activities of industrial vessels. The duration of fishing, the distances travelled, and the frequency of fishing trips have all been disrupted. A local fisherman claimed:

We are no longer able to leave our net out at sea during the night or [to] fish, which is a common practice in Ghana. That's what we all do in our communities; it's the best technique for us, but we can't do it anymore because of these large vessels in our fishing zones (Fisherman, May 21, 2021)

The loss of access to and control over fisheries resources in Ghana has affected the incomes and livelihoods of these local fishers. Small-scale fisheries households that were economically secure are now poorer compared to the average household in Ghana's coastal regions (Ofori-Danson et al. 2013). Local fishers use their physical assets (fishing gear) to acquire economic assets (harvest fish); therefore, these dimensions are intertwined in terms of achieving or not achieving their livelihood goals. However, by disrupting their physical assets, the increase in industrial fishing exploitation has negatively affected these fishers' economic participation. The research participants also accused industrial fishing vessels of direct rivalry in fish marketing by using freezing technologies to preserve the freshness of small pelagic catch. One local processor told us:

They [small-scale fishers] waste so much fuel because they have to travel so far, and by the time they land, the little fish they harvested would have also gone bad, and we can't afford to pay a high price for bad fish (Fish processor/trader, July 29, 2021)

Fish trading and processing

Coastal women involved in the processing and selling of fish claimed they are in a precarious position due to declining coastal fisheries, and that obtaining the required quantity of fish from local communities has become difficult and sometimes impossible. They now need to travel long distances to different community landing beaches to buy fish in small quantities. A processor said:

When we are unable to get fish from this beach, we must travel to other communities such as Edina and Fetteh to purchase fresh fish. As a result, the fish becomes more expensive, and selling it becomes a difficulty (Fish processor/traders, March 10, 2021)

Additional operational costs include transportation and ice. Unable to meet their increased operational costs associated with the declining fisheries, local fishers have increased catch prices disproportionately, which affects the profits of the processors/traders. The local women explained that apart from the difficulty in obtaining fresh fish, the marketing of processed fish has also become challenging because it has become more expensive for consumers due to the associated operational expenses and shortages.

Additionally, most of the fish traders explained that they can no longer store fish and thus maintain competitive prices due to the fishers' insistence on prompt payment. They mostly stockpile the smoked fish for better prices—sometimes up to a month—but due to the fisheries' decline, they are unable to store smoked fish for a lengthy period due to fishers' demands. As a result, processed fish are occasionally sold at lower prices. One fish trader said:

The fishermen bother us to get their money back within one or two days after giving you the fish. So, we are unable to keep the fish on the shelf for long. We have no choice but to sell it at whatever price is offered to us. When this happens, we are always at a loss (Fish processor/trader, May 26, 2021)

Furthermore, the local processors claimed the control of small-scale fishery markets has shifted away from them to a small group of financially well-resourced businesswomen who are mostly from the communities but do not belong to the small-scale fisheries local networks and who obtain illegally transhipped small pelagic fish species (saiko) from industrial trawlers. These individuals also enjoy a consistent supply with little operational cost and frequently supply fish to markets at a discounted retail price. By maintaining the market monopoly over customers and distorting the prices of locally processed fish, such actors disadvantage the local processors, who are mostly local women facing large operating costs and a limited supply. A chief fish processor explained:

Businesswomen from the city with money have taken over our job because they call the shots at the shores and at the markets. When you go to the market, there is fish alright, but about 95% of the fish in the market comes from the industrial trawler fishers (Chief fish processor/trader, February 15, 2021)

Social assets

Social exclusion and disconnection

The small-scale fisheries decline has impacted the organisation and interactions of Ghana's coastal fishing communities, both at the state level and within the local communities. Small-scale fisheries actors are being excluded from local fishing organisations at the community level due to livelihood disruption caused by the decline of local fisheries. Historically, the communities along the coast have been linked and organised through kinship and occupation (Bortei-Doku 1995; Kronenfeld 1980). Thus, local fishing community members demonstrate solidarity through these kinship networks and established social and economic groups. Fishing for small-scale commercial purposes and fish processing is one of the most socially organised economic activities in the coastal communities, with fishers and processors/traders supporting each other both financially and non-financially during celebratory social occasions. Boat owners and crew members share a close bond, living and working together as a family and finding personal fulfilment via fishing, while fishers gathering daily at the local landing beach strengthens the community cohesion. Women participants reported that when they gather on the shore to buy fish, they discuss their sexual and family lives. A female local processor recalled:

This area [the landing beach] serves as a gathering place for women; we came here to wait for the canoes and, while waiting, we discussed our families and women's issues (Chief fish processor/trader, January 30, 2021).

Another woman said:

That joyful period of our lives has passed; we no longer see one another daily (Fish processor/trader, April 23, 2021)

The participating local actors explained that these support structures have been affected by the declining incomes and other disruptions in fishing activities. They claimed small-scale fishermen are disengaging from coastal communities' shared goals and identities. A fisherman explained:

We fishermen were born into a loving and supportive community, but the current situation caused by the industrial trawlers has shifted that sense of community. We want and desire to assist each other, but the resources to provide that level of assistance are simply not available. The community thinks fishers have no place and reputation anymore (Fisherman, April 19, 2021)

These subjective social, well-being, and economic interactions considerations have been significantly disrupted in the Ghanaian coastal fisheries. Fishermen told us of emotional encounters with crew members who had to relocate to different towns due to low catches. Moreover, fishing community connections at local landing beaches, processing sites, or markets have all been weakened. A chief fisherman said:

We support one another, mend and drag each other's fishing nets while singing Indigenous rhythms; this served as a customary way of invocating the ancestral spirits of the sea and our fathers who lived and worked as fishers in this community (Chief fisherman, July 1, 2021)

Local fishermen told us that the state has failed to protect and prioritise their livelihoods at the broader state level, so they feel disconnected from the successive administrations. The relationship between government institutions (national and local) and Indigenous fishers over fisheries management, citizenship responsibilities, and governance has remained antagonistic because of the saiko activities of the industrial fishers. Local fishers and local NGOs attribute the decline in small-scale fisheries to political decisions that have allowed industrial vessels into maritime space and to subsequent failures to manage illegal activities (EJF 2018). During a focus group discussion with local fishermen, one participant summarised this concern:

As a community, we are united in our belief that the government has failed us. They have let us down. Governments' unpopular decisions over the years to expand industrial fishing have ruined our livelihoods. We do not appear to matter to the government; if we did, more would have been done to alleviate our plight. From artisanal fishermen to women processors, nothing about us is significant to the government (Fisherman, June 1, 2021)

Conflict and social cohesion

Emerging evidence reveals a decline in social cohesion because of increased fisheries conflicts between small-scale fishers, between small-scale fishers and fishmongers, and between processors, traders and customers (Ameyaw et al. 2021; Alexander et al. 2018). In coastal Ghana, conventional norms that assign rights to cast nets and harvest fish based on first sighting are now flouted, and fishermen frequently disagree over who spotted the fish first. A fisher explained:

What happens is that when we notice a canoe throwing its net in a particular area of the sea, it indicates that they have spotted fish, so we also get close to cast our net … in such situations, our nets overlap on each other and that can result in a heated argument and fight at sea (Fisherman, April 2, 2021)

Furthermore, as observed by Overå (2003), the prerequisite for the success of female entrepreneurs in Ghanaian coastal fisheries is a loyal and trustworthy male (fisherman) partner. However, the decline in small-scale fisheries has affected women's cooperation with local fishers. Women processors provide fuel for the fishing trip and, in some cases, help fishers repair their fishing gear. They also often become responsible for crewmembers' food, mainly using the profit from the sale of processed fish. In exchange, the fishers deliver the catch to these processors/traders. The processors explained that the decline in profits due to the limited supply and the associated operational cost has affected their ability to meet the expected expenditures for the fishing trips. As a result, most fishers have become disloyal and sell their catch to the highest bidder. Many fish processors do not have immediate cash reserves for payment and rely on the conventional fisher-processor arrangement, which is now dysfunctional. Besides, the catch price in the coastal communities is commonly determined by a committee of local fish processors (or chief fish processors), but fishers now disregard this convention as they look for the highest bidder. Moreover, the lack of catch frequently results in misunderstandings between fishers and the fish processors/traders who sponsor the fishing trips.

Heritage, traditions, and norms

Fishing communities in Ghana are inextricably linked to broader socio-cultural beliefs, traditions, and taboos as a source of identity and social well-being (Bennett 2002; Dosu 2017). The declining economic status of fishing discourages young adults from pursuing it as an occupation. Local fishers and processors/traders explained that their responsibility is to bequeath the fishing tradition by initiating young family members into adulthood with fishing gear and equipment to begin their working lives. For chief fishermen's families, this is particularly important as the elder male son must inherit the father's fishing occupation to retain the "chief fisher" title in that family. A Chief fisherman reported:

When I ask my son to help me mend my fishing net, he refuses. He's not interested in learning about my work, let alone applying it … it means he disapproves of my occupation. That's how badly we are losing our family heritage (Chief Fisherman, February 25, 2021)

Additionally, industrial fishers disregard local community norms by, for example, violating restrictions prohibiting fishing on designated non-fishing days (most commonly Tuesday) and during coastal festivities. Local festivals are celebrated at the end of the fishing season at the community level. During abundant catches, a portion of each daily catch is set aside for these seasonal and calendar celebrations. The fishermen explained that the decline in coastal fisheries and fishing livelihood has significantly impacted the local social activities that define their identity as fishers. One of them summarised the situation:

At the end of the fishing year, we saved money for drinks, food, clothes, and gifts for each crew member. We did so because we had a good catch and wanted to keep celebrating our fishing heritage. We felt a strong sense of community and joy, but all these memorable days are gone because of the China saiko fishers (Chief fisherman, May 19, 2021)

Women's identity and prestige: "a good wife"

Gender concerns have not been adequately addressed in most studies of fishing livelihoods (Harper et al. 2017; Harper et al. 2013; Torell et al. 2019). In Ghana, the economic position, identity, and social prestige of coastal women are linked to small-scale fisheries, which are important sources of income for them (Coastal Resources Center 2018). Women exclusively control and make decisions regarding post-harvest management activities; they purchase the local catch, process it, and then market it (Ameyaw et al. 2020; Torell et al. 2019). Generally, women in small-scale fisheries use their income to maintain their homes, and a portion of the fish is consumed by the household (Harper et al. 2013; Weeratunge et al. 2010).

According to the local women we spoke to, the processing and trading in small-scale fisheries have traditionally been female occupations, proudly passed down from generation to generation. However, the women claimed that in most communities, fishers now bypass them to sell the catch to former fishermen. Members of fishing crews who have lost their livelihoods because of declining fisheries have assumed the role of intermediaries between fishermen and women traders and processors. The women revealed that former crewmembers exploit both their relational advantage with the fishers and their ability to travel out to sea to obtain the fish. The women, who are primarily involved in either processing or marketing, are unable to meet fishers offshore to collect the catch. The leader of the processors explained:

One major concern for us here is that the fish selling and processing business was traditionally the preserve of women. But now the men have taken up this occupation … the fishermen will sell the fish to men traders offshore, who will, in turn, sell it to buyers [women] on shore. The China people have caused all these problems, because the men would have gone fishing and we the women control the processing and trading (Chief fish processor/trader, January 28, 2021)

In this context, the women frequently blamed the Chinese investors in industrial fishing and their Ghanaian allies (politicians, fisheries managers, and businesspeople) for their livelihood predicaments.

The decline in small-scale fisheries has added to the burdens of coastal women. Processors and traders claimed that their social standing as "good wives" has deteriorated due to their inability to access food from the fish business. Local fish traders/processors are culturally responsible for maintaining their homes and the crew members with the proceeds from their fish businesses. Based on their traditional role as fishers' wives, the women said they have lost their social status, as well as becoming impoverished. Bartering fish for other food supplies to meet the family's nutrition needs is no more common. One processor said:

Food was not bought with money; the women who brought foodstuffs from other communities to our market gave it out to us and in return, took fish … things have gotten out of hand and I feel like am not a woman (Fish processor/trader, June 8, 2021)

Natural assets

Ecological damage and fishing capacity

Local knowledge helps small-scale fishers determine where to fish, how to fish, and what species to target. It constitutes their human capital. Local fishers reported that industrial fishing vessels either use technology to crush rocks or trawl the seabed to catch crustaceans, destroying specific ocean features and fauna and severely altering the marine ecosystem and landscape. This affects their ability to forecast changes in the fishing seasons and to predict coastal fishery behaviour—a traditional practice. A chief fisherman explained:

These vessel operators have machines that have broken all the rocks into pieces in order to catch octopus, shrimps and crabs. They have wiped out the sea's features which we use as signals to trace the fish or target the fish with the appropriate gear (Chief fisherman July 24, 2021)

Fishing around areas where dolphins and whales are observed, particularly on the western side of Axim and Half-Assini, is usually productive (Banful 2021). However, such mammals are more difficult to find due to industrial trawlers' intensive harvesting of them (Van Waerebeek and Perrin 2007). For example, the International Whaling Commission (IWC 2021) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN 2010) classified Atlantic humpback dolphins and the West African manatees as vulnerable or critically endangered, due largely to their deaths as bycatch, targeted capture, habitat degradation, and prey depletion due to overfishing. Additionally, fishers participating in this study said that seasonal variations have become unpredictable due to industrial trawlers' destructive activities, which affect trip planning. One fisher explained:

Every fish has its seasonal time they come down. Herrings and salmon are in July, August, and September. Anchovies come every three months. Lobsters and octopus stay at one place in the sea … all this has changed because of the trawler people (Fisherman April 5, 2021)

While small-scale fishers emphasise the role of industrial trawling, other anthropogenic factors such as climate change are also likely to exacerbate fishing decline and contribute to the livelihood vulnerability of communities in Ghana (Freduah et al. 2017; Pabi et al. 2015).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the modernisation of Ghana's historical fisheries (Overå, 2011) and the current blue economy aspirations of industrial fishing have considerably impacted coastal fishing livelihoods in that country. As innovation and globalisation accelerate marine transformation, research into coastal fishing livelihoods is becoming crucial to understanding their social, economic, and ecological effects. Blue economy initiatives, which have been compared to earlier maritime transitions are putting pressure on poorer coastal communities, particularly small-scale fisheries. In the context of Ghana, industrial fishing seems likely to intensify and overwhelm small-scale fishing in pursuit of the blue economy, with considerable economic and social consequences for coastal livelihoods. We found in Ghana that industrial fishing has already harmed fisheries resources, caused damage to gear, weakened the local market systems, and diminished the positions of coastal fishing actors (i.e., small-scale fishers and traders), thereby jeopardising the economic, social, and cultural formations associated with the country's coastal fishing value chains. With the multiple dimensions of coastal fisheries' livelihoods now eroding, the sustainability of the value chains is also at risk of collapse. The small-scale fisheries and the coastal communities in Ghana may be approaching a "tipping point" (Serrao-Neumann et al. 2016) beyond which they cannot operate as they have in the past.

Fisheries scientists and environmental non-governmental organisations are optimistic that recent progress by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) at its 12th Ministerial Conference to address the issue of 'harmful' fisheries subsidies on a global scale will help to reduce the phenomena (WTO 2022). While these international actions are underway to address the effects of fisheries subsidies, their success may eventually have beneficial spillover effects at the local level for small-scale fisheries. In the case of Ghana at the moment, we recommend that the government of Ghana take immediate steps to reduce the number and capacity of industrial fishing vessels to enable local small-scale fisheries to rebuild. The Ghana Fisheries Management Plan (2015–2019) made a similar proposal to cut all fleet sizes to reduce overcapacity in the country's coastal waters (MoFAD 2015). However, the management plan expired in 2019 without any tangible actions and the political will to implement the proposal. Establishing a closed fishing season for both the industrial fishing fleet and small-scale fishing in Ghana during the past few years is a big step towards allowing adult fish to spawn and increasing their production. Nonetheless, this management decision has severely impacted coastal fishing actors who have no other source of income or investments to rely on during the restricted fishing season. Additionally, we recommend that the recently established Fishery Enforcement Unit (FEU) strictly enforce the country's law on fisheries' spatial limits. Moreover, donor-funded initiatives to implement participatory and co-management in Ghana's fisheries and to build marine protected areas (Kassah and Asare 2022) must provide an equitable and inclusive space for small-scale fishing as a matter of social and economic rights (Jentoft et al. 2022; Bennett et al. 2019). As a form of adaptation, future research may examine the social and political agency available to small-scale operators in Ghana.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the research participants' confidentiality and privacy concerns, the datasets collected for this research may not be made publicly available except in limited circumstances.

Notes

The lead author could not travel to Ghana for the interviews, therefore he worked with the fourth co-author, who was in Ghana.

References

Acquay HK (1992) Implications of structural adjustment for Ghana’s marine fisheries policy. Fish Res 14(1):59–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-7836(92)90073-3

Adger WN (2006) Vulnerability. Glob Environ Chang 16(3):268–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.006

Akpalu W, Eggert H (2021) The economic, social and ecological performance of the industrial trawl fishery in Ghana: application of the FPIs. Mar Policy 125:104241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104241

Akyeampong E (2007) Indigenous knowledge and maritime fishing in West Africa: the case of Ghana. Tribes Tribals 1:173–182

Alexander SM, Bodin Ö, Barnes ML (2018) Untangling the drivers of community cohesion in small-scale fisheries. Int J the Commons 12(1):519–547. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.843

Allison EH, Horemans B (2006) Putting the principles of the sustainable livelihoods approach into fisheries development policy and practice. Mar Policy 30(6):757–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2006.02.001

Allison EH, Ellis F (2001) The livelihoods approach and management of small-scale fisheries. Mar Policy 25(5):377–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-597X(01)00023-9

Adjei M, Overå R (2019) Opposing discourses on the offshore coexistence of the petroleum industry and small-scale fisheries in Ghana. Extr Ind Soc 6(1):190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2018.09.006

Ameyaw AB, Breckwoldt A, Reuter H, Aheto DW (2020) From fish to cash: analysing the role of women in fisheries in the western region of Ghana. Mar Policy 113:103790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103790

Ameyaw GA, Tsamenyi M, McIlgorm A, Aheto DW (2021) Challenges in the management of small-scale marine fisheries conflicts in Ghana. Ocean Coast Manag 211:105791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105791

Atta-Mills J, Alder J, Sumaila UR (2004) The decline of a regional fishing nation: the case of Ghana and West Africa. Nat Res Forum 28(1):13–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0165-0203.2004.00068.x

Africa Union (2019). African blue economy strategy. Nairobi, Kenya: https://www.au-ibar.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/sd_20200313_africa_blue_economy_strategy_en.pdf

Ayilu, R. K., Fabinyi, M., & Barclay, K. (2022). Small-scale fisheries in the blue economy: Review of scholarly papers and multilateral documents. Ocean & Coastal Management, 216, 105982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105982

Ayilu RK, Antwi-Asare TO, Anoh P, Tall A, Aboya N, Chimatiro S, & Dedi S (2016) Informal artisanal fish trade in West Africa: improving cross-border trade. Penang, Malaysia: WorldFish. Program Brief: 2016–37. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12348/3864

Banful K (2021) Nobody likes dolphin meat, but times are hard. Los Angeles Review of Book. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/nobody-likes-dolphin-meat-but-times-are-hard/ (accessed 6 April 2022)

Bank of Ghana (2008) The fishing sub-sector and Ghana's economy. Retrieved from https://www.bog.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/fisheries_completerpdf.pdf

Bavinck M (2005) Understanding fisheries conflicts in the South -a legal pluralist perspective. Soc Nat Resour 18(9):805–820. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920500205491

Belhabib D, Cheung WWL, Kroodsma D, Lam VWY, Underwood PJ, Virdin J (2020) Catching industrial fishing incursions into inshore waters of Africa from space. Fish Fish 21(2):379–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12436

Belhabib D, Sumaila UR, Lam VW, Zeller D, Le Billon P, Kane EA, Pauly D (2015) Euros vs. Yuan comparing European and Chinese fishing access in West Africa. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118351

Bennett E (2002) The challenges of managing small-scale fisheries in West Africa. CEMARE Rep 7334:61

Bennett E, Bannerman P (2002) The management of conflict in tropical fisheries. CEMARE Final Technical Report, 7334

Bennett NJ, Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Blythe J, Silver JJ, Singh G, Andrews N, Sumaila UR (2019) Towards a sustainable and equitable blue economy. Nat Sustain 2(11):991–993. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0404-1

Bennett NJ, Dearden P (2014) Why local people do not support conservation: community perceptions of marine protected area livelihood impacts, governance and management in Thailand. Mar Policy 44:107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2013.08.017

Berkes F, Hughes TP, Steneck RS, Wilson JA, Bellwood DR, Crona B, Worm B (2006) Globalisation, roving bandits, and marine resources. Science 311(5767):1557–1558. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1122804

Bolaky B (2020) Operationalising blue economy in Africa: the case of south west Indian Ocean, ORF Issue Brief No. 398, September 2020, Observer Research Foundation

Bortei-Doku E (1991) Migrations in artisanal marine fisheries among Ga-adangbe fishermen and women in Ghana. In: Haanonsen IM, Diaw CM (eds) Fishermen’s migration in West Africa. IDAF, Cotonou

Bortei-Doku E (1995) Kinsfolk and workers: social aspects of labour relations among Ga-Dangme Coastal fisherfolk. ORSTROM, 134–151. https://hdl.handle.net/10535/5780

Bryant RL (1992) Political ecology: an emerging research agenda in Third-World studies. Polit Geogr 11(1):12–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/0962-6298(92)90017-N

Campling L, Colás A (2021) Capitalism and the sea: the maritime factor in the making of the modern world. London Verso Books

Chambers R, Conway G (1992) Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century, IDS Discussion Paper 296, Brighton: IDS

Childs JR, Hicks C (2019) Securing the blue: political ecologies of the blue economy in Africa. J Polit Ecol 26(1):323–340. https://doi.org/10.2458/v26i1.23162

Coastal Resources Center (2018) Fisheries and food security: a briefing from the USAID/Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project, January 2018. The USAID/Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP). Narragansett, RI: Coastal Resources Center, Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island. GH2014_POL055_CRC 15 pp. Report on analysis of non-traditional exports

Cohen PJ, Allison EH, Andrew NL, Cinner J, Evans LS, Fabinyi M, Ratner BD (2019) Securing a just space for small-scale fisheries in the blue economy. Front Mar Sci 6:171. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00171

De Haan L, Zoomers A (2005) Exploring the frontier of livelihoods research. Dev Chang 36(1):27–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2005.00401.x

DfID (1999). Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. Department for International Development (DFID), London, UK

Dosu, G. (2017). Perceptions of socio-cultural beliefs and taboos among the Ghanaian fishers and fisheries authorities. A case study of the Jamestown fishing community in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana (Master's thesis, The Arctic University of Norway)

Dovlo E, Amador K, Nkrumah B (2016) Report on the 2016 Ghana Marine Canoe Frame Survey. Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development, Fisheries Scientific Survey Division, Information Report No 36

Economic Commission for Africa (2016) Africa's Blue economy: a policy handbook. Economic Commission for Africa, Retrieved from https://www.uneca.org/publications/africas-blue-economy-policy-handbook

Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF). (2018). China's hidden fleet in West Africa: a spotlight on illegal practices within Ghana's industrial trawl sector. Environmental Justice Foundation, London, UK. [online] URL: https://ejfoundation.org/reports/ chinas-hidden-fleet-in-west-africa-a-spotlight-on-illegal-practiceswithin-ghanas-industrial-trawl-sector

Eriksson H, Österblom H, Crona B, Troell M, Andrew N, Wilen J, Folke C (2015) Contagious exploitation of marine resources. Front Ecol Environ 13(8):435–440. https://doi.org/10.1890/140312

European Investment Bank, (2021). African and European Blue Economy leaders share sustainable investment best practices. https://www.eib.org/en/press/all/2021-124-african-and-european-blue-economy-leaders-share-sustainable-investment-best-practices (accessed 13 October 2021)

Failler P, Binet T (2011) A critical review of the European Union West African fisheries agreements. Oceans the new frontier. AFD, IDDRI, TERI, 166–170

Feeny D, Hanna S, McEvoy AF (1996) Questioning the assumptions of the" tragedy of the commons" model of fisheries. Land Econ. https://doi.org/10.2307/3146965

Ferrol-Schulte D, Wolff M, Ferse S, Glaser M (2013) Sustainable livelihoods approach in tropical coastal and marine social–ecological systems: a review. Mar Policy 42:253–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2013.03.007

Ficke AD, Myrick CA, Hansen LJ (2007) Potential impacts of global climate change on freshwater fisheries. Rev Fish Biol Fish 17(4):581–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-007-9059-5

Freduah G, Fidelman P, Smith TF (2018) Mobilising adaptive capacity to multiple stressors: insights from small-scale coastal fisheries in the Western Region of Ghana. Geoforum 91:61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.026

Freduah G, Fidelman P, Smith TF (2017) The impacts of environmental and socio-economic stressors on small scale fisheries and livelihoods of fishers in Ghana. Appl Geogr 89:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.09.009

Friends of the Nation (2015). Baseline for prosecutions: summary of fisheries arrests and prosecution in the western and eastern commands. Narragansett, RI: Coastal Resources Center, Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island and Friends of the Nation. GH2014_POL013_FoN. 30 pp

Ghana Statistical Service (2010). Population and Housing Census Report. https://statsghana.gov.gh

Ghana Health Service (2021). Covid-19: Ghana's outbreak response management updates. Retrieved from https://www.ghanahealthservice.org/covid19/ (accessed 29 June 2021)

Hardin G (1998) Extensions of “the tragedy of the commons.” Science 280(5364):682–683. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.280.5364.682

Harper S, Grubb C, Stiles M, Sumaila UR (2017) Contributions by women to fisheries economies: insights from five maritime countries. Coast Manag 45(2):91–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2017.1278143

Harper S, Zeller D, Hauzer M, Pauly D, Sumaila UR (2013) Women and fisheries: contribution to food security and local economies. Mar Policy 39:56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2012.10.018

Havice E, Campling L (2021) Industrial fisheries and oceanic accumulation. In: Akram-Lodhi H, Dietz K, Engels B, McKay BM, Elgar E (eds) Handbook of critical agrarian studies. Edward Elgar Publishing, United Kingdom

IHH (2021). A virtual webinar providing a "first-look" at some key findings from the upcoming Illuminating Hidden Harvest (IHH) report. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2dheBvXcABE (accessed January 2022)

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (2022) Thematic assessment of the sustainable use of wild species of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.6448567

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (2021). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.3. Online at: http://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed 23 October 2021)

International Whaling Commission (IWC 2021). Humpback Dolphins. Online at https://iwc.int/humpback-dolphin (accessed 23 October 2021)

Jentoft S, Chuenpagdee R, Said AB, Isaacs M (2022) Blue justice small-scale fisheries in a sustainable ocean economy. MARE publication series. Springer, Cham

Jonsen K, Jehn KA (2009) Using triangulation to validate themes in qualitative studies. Qual Res Organ Manag 4(2):123–150. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465640910978391

Kassah JE, Asare C (2022) Conflicts in the artisanal fishing industry of Ghana: reactions of fishers to regulatory measures. In: Blue justice pp. 99–118. Springer: Cham

Kolding J, van Zwieten PA (2011) The tragedy of our legacy: how do global management discourses affect small scale fisheries in the south?: In: Forum for development studies Vol 38, pp 267–297, Routledge

Kronenfeld D (1980) A formal analysis of Fanti Kinship terminology (Ghana). Anthropos 75(3/4):586–608

Kuczenski B, Poulsen CV, Gilman EL, Musyl M, Geyer R, Wilson J (2022) Plastic gear loss estimates from remote observation of industrial fishing activity. Fish Fish 23(1):22–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12596

Lazar N, Yankson K, Blay J, Ofori-Danson P, Markwei P, Agbogah K, Bannerman P, Sotor M, Yamoah KK, Bilisini WB (2018) Status of the small pelagic stocks in Ghana in 2018. Scientific and Technical Working Group. USAID/Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP). Coastal Resources Center, Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island. GH2014_SCI_082_CRC. 16 pp

Longo SB, Clausen R (2011) The tragedy of the commodity: the overexploitation of the Mediterranean bluefin tuna fishery. Organ Environ 24(3):312–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026611419860

Marshall C, Rossman GB (2014) Designing qualitative research. Sage Publications, London

Mallory TG (2016) Fisheries subsidies in China: quantitative and qualitative assessment of policy coherence and effectiveness. Mar Policy 68:74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.01.028

Mansfield B (2010) Modern industrial fisheries and the crisis of overfishing. In: Global political ecology (pp 98–113), Routledge

Martins IM, Medeiros RP, Di Domenico M, Hanazaki N (2018) What fishers’ local ecological knowledge can reveal about the changes in exploited fish catches. Fish Res 198:109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2017.10.008

McConnaughey RA, Hiddink JG, Jennings S, Pitcher CR, Kaiser MJ, Suuronen P, Hilborn R (2020) Choosing best practices for managing impacts of trawl fishing on seabed habitats and biota. Fish Fish 21(2):319–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12431

McDougall C, Akester M, Notere Boso D, Choudhury A, Hasiba Z, Karisa H, Scott J (2020). Ten strategies for research quality in distance research during COVID-19 and future food system shocks. Penang, Malaysia: CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems. Program Brief: FISH-2020–11

McWhinnie SF (2009) The tragedy of the commons in international fisheries: an empirical examination. J Environ Econ Manag 57(3):321–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2008.07.008

Mindjimba K, Rosenthal I, Diei-Ouadi Y, Bomfeh K & Randrianantoandro A (2019) FAO-Thiaroye processing technique: towards adopting improved fish smoking systems in the context of benefits, trade-offs and policy implications from selected developing countries. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Paper no. 634. Rome. FAO. 160 pp

Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development (MoFAD) (2015). National fisheries management plan, Government of Ghana pp 48

Nolan C (2019) Power and access issues in Ghana’s coastal fisheries: A political ecology of a closing commodity frontier. Marine Policy 108:103621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103621

Nunoo F, Boateng JO, Ahulu AM, Agyekum KA, Sumaila UR (2009) When trash fish is treasure: the case of Ghana in West Africa. Fish Res 96(2–3):167–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2008.10.010

Nunoo FKE, Asiedu B, Amador K, Belhabib D, Lam V, Sumaila R, Pauly D (2014) Marine fisheries catches in Ghana: historic reconstruction for 1950 to 2010 and current economic impacts. Rev Fish Sci Aquac 22(4):274–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/23308249.2014.962687

O’Neill ED, Crona B (2017) Assistance networks in seafood trade–a means to assess benefit distribution in small-scale fisheries. Mar Policy 78:196–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.01.025

Ofori-Danson PK, Sarpong DB, Sumaila UR, Nunoo F, Asiedu B (2013) Poverty measurements in small-scale fisheries of Ghana: a step towards poverty eradication. J Curr Res J Soc Sci 5(3):75–90

Okafor-Yarwood I, Belhabib D (2020) The duplicity of the European Union common fisheries policy in third countries: evidence from the Gulf of Guinea. Ocean Coast Manag 184:104953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.104953

Okeke-Ogbuafor N, Gray T, Stead SM (2020) Is there a “wicked problem” of small-scale coastal fisheries in Sierra Leone? Mar Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.02.043

Overå R (2003) Gender ideology and manoeuvring space for female fisheries entrepreneurs. Inst Afr Stud Res Rev 19(2):49–62

Overå R (2005) Institutions, mobility and resilience in the Fante migratory fisheries in West Africa. Trans Hist Soc Ghana 9:103–123

Overå R (2011) Modernisation narratives and small-scale fisheries in Ghana and Zambia. Forum Dev Stud 38(3):321–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2011.596569

Owusu V, Andriesse E (2020) From open access regime to closed fishing season: lessons from small-scale coastal fisheries in the Western Region of Ghana. Mar Policy 121:104162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104162

Pabi O, Codjoe SNA, Sah NA, & Appeaning Addo I (2015) Climate change linked to failing fisheries in coastal Ghana. IDRC. http://hdl.handle.net/10625/54163

Parker RW, Blanchard JL, Gardner C, Green BS, Hartmann K, Tyedmers PH, Watson RA (2018) Fuel use and greenhouse gas emissions of world fisheries. Nat Clim Chang 8(4):333–337. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0117-x

Parker RW, Tyedmers PH (2015) Fuel consumption of global fishing fleets: current understanding and knowledge gaps. Fish Fish 16(4):684–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12087

Pauly D, Zeller D (Eds.) (2015) Catch reconstruction: concepts, methods and data sources. Online Publication. Sea around us. University of British Columbia. www.seaaroundus.org

Pauly D, Watson R, Alder J (2005) Global trends in world fisheries: impacts on marine ecosystems and food security. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 360(1453):5–12

Robbins P (2011) Political ecology: a critical introduction. Wiley, London

Sala A, Damalas D, Labanchi L, Martinsohn J, Moro F, Sabatella R, Notti E (2022) Energy audit and carbon footprint in trawl fisheries. Sci Data 9(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01478-0

Schuhbauer A, Skerritt DJ, Ebrahim N, Le Manach F, Sumaila UR (2020) The global fisheries subsidies divide between small- and large-scale fisheries. Front Mar Sci 7:539214. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.539214

Schorr DK (2005) Artisanal fishing: promoting poverty reduction and community development through new WTO rules on fisheries subsidies-an issue and options paper. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Economics and Trade Branch (ETB) Geneva.

Scoones I (2015) Sustainable livelihoods and rural development. Blackpoint, Nova Scotia, Fernwood Pub

Scoones I (1998) Sustainable rural livelihoods: a framework for analysis, IDS Working Paper 72, Brighton: IDS

Sen A (1981) Poverty and famines: an essay on entitlement and deprivation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Seto KL (2017) Local fishery, global commodity: conflict, cooperation, and competition in Ghana’s coastal fisheries (Doctoral dissertation, UC Berkeley)

Serrao-Neumann S, Davidson JL, Baldwin CL, Dedekorkut-Howes A, Ellison JC, Holbrook NJ, Morgan EA (2016) Marine governance to avoid tipping points: can we adapt the adaptability envelope? Mar Policy 65:56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.007

Seyram DE (2020) Factors influencing the use of "Ahotor" oven among fish smokers in Ghana (Doctoral dissertation, University of Ghana)

Silver JJ, Gray NJ, Campbell LM, Fairbanks LW, Gruby RL (2015) Blue economy and competing discourses in international oceans governance. J Environ Dev 24(2):135–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496515580797

Smith-Godfrey S (2016) Defining the blue economy. Marit Aff J Natl Marit Found India 12(1):58–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/09733159.2016.1175131

Sumaila UR, Ebrahim N, Schuhbauer A, Skerritt D, Li Y, Kim HS, Pauly D (2019) Updated estimates and analysis of global fisheries subsidies. Mar Policy 109:1036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103695

Sumaila UR, Lam V, Le Manach F, Swartz W, Pauly D (2016) Global fisheries subsidies: an updated estimate. Mar Policy 69:189–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.026

Sumaila UR, Cheung WW, Lam VW, Pauly D, Herrick S (2011) Climate change impacts on the biophysics and economics of world fisheries. Nat Clim Chang 1(9):449–456. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1301

Teh LC, Sumaila UR (2013) Contribution of marine fisheries to worldwide employment. Fish Fish 14(1):77–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2011.00450.x

Torell E, Bilecki D, Owusu A, Crawford B, Beran K, Kent K (2019) Assessing the impacts of gender integration in Ghana’s fisheries sector. Coast Manag 47(6):507–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2019.1669098

Van Waerebeek K, Perrin WF (2007) Conservation status of the Clymene dolphin in West Africa. In: Document CMS/ScC14/Doc. 5 presented to 14th Meeting of the CMS Scientific Council

Walker BLE (2001) Sisterhood and seine-nets: engendering development and conservation in Ghana’s marine fishery. Prof Geogr 53(2):160–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00277

Wang Q, Wang S (2022) Carbon emission and economic output of China’s marine fishery–a decoupling efforts analysis. Marine Policy 135:104831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104831

Weeratunge N, Snyder KA, Sze CP (2010) Gleaner, fisher, trader, processor: understanding gendered employment in fisheries and aquaculture. Fish Fish 11(4):405–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00368.x

WTO, (2022). Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies. Retrieved from https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT/MIN22/33.pdf&Open=True (accessed 23 August 2022)

Funding

This research is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship as part of the first author’s PhD, and by the Australian Research Council (DP180100965) awarded to the second author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author conceptualised the research, obtained ethical approval, and wrote the first draft. The second and third authors supervised the research and contributed to analysis. The first and fourth authors conducted the fieldwork and managed data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Human Research Ethics Committee of University of Technology Sydney gave ethical approval for this study. Fieldwork procedures followed the required ethical guidelines, and all participants provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayilu, R.K., Fabinyi, M., Barclay, K. et al. Blue economy: industrialisation and coastal fishing livelihoods in Ghana. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries 33, 801–818 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-022-09749-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-022-09749-0