Abstract

People often discriminate based on negative or positive stereotypes about others. Important examples of this are highlighted by the theory of ambivalent sexism. This theory distinguishes sexist stereotypes that are negative (hostile sexism) from those that are positive (benevolent sexism). While both forms of sexism are considered wrong toward women, hostile sexism seems intuitively worse than benevolent sexism. In this article, we ask whether the difference between discriminating based on positive vs. negative stereotypes in itself makes a morally relevant difference. We suggest that it does not. By examining a number of prominent accounts of what makes discrimination wrong, we defend the Moral Irrelevance View according to which stereotype valence is irrelevant to the moral evaluation of discrimination, all else equal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

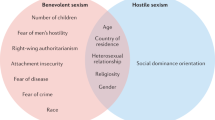

Negative stereotypes attribute traits or skills that are generally evaluated unfavorably by the person holding the stereotype (and society more broadly).Footnote 1 If an employer does not hire Amanda because they hold the negative stereotype that women are stupid (and that Amanda would therefore perform poorly on the job), they hold a negative stereotype toward Amanda. Positive stereotypes, on the other hand,'attribute traits or skills that are generally evaluated favorably by the [person holding the stereotype]' (Davis 2016, p. 486). If an employer does not hire Bella because they hold the positive stereotype that women are highly intelligent (and that Bella would therefore get bored at the job and perform poorly), they hold a positive stereotype toward Bella. According to the theory of ambivalent sexism (Glick and Fiske 2001), Amanda is subject to hostile sexism, whereas Bella is subject to benevolent sexism (see, e.g., Barreto and Doyle 2023).

Intuitively, it might seem that discriminating based on a negative stereotype is morally worse than discriminating based on a positive stereotype. For example, in research on how people perceive ambivalent sexism,'benevolent sexism is considered more acceptable [than hostile sexism], and at times even flattering' (Barreto and Doyle 2023, p. 100; see also Moya et al. 2007). Such verdicts are captured by the following view:

The Moral Relevance View: All else equal, stereotype valence is relevant to the moral evaluation of discrimination.

According to the Moral Relevance View, what the former employer does (discriminating based on a negative stereotype) is worse than what the latter employer does (discriminating based on a positive stereotype). On this view, it is morally worse to believe of another that they are stupid qua their group membership than that they are intelligent qua their group membership. The Moral Relevance View contrasts with the following view:

The Moral Irrelevance View: All else equal, stereotype valence is irrelevant to the moral evaluation of discrimination.

According to this view, what the former employer does is not morally worse than what the latter employer does. This is true even though the former believes that the candidate is stupid, and the latter believes that the candidate is intelligent.

Which view is right? In this paper, we argue that the Moral Relevance View cannot survive scrutiny. There is no plausible ground underlying the Moral Relevance View that can explain why stereotype valence in itself is relevant to the wrongness of discrimination. Thus, our paper supports, at least indirectly,Footnote 2 the Moral Irrelevance View. This is significant for several reasons. First, there is an intuitive pull in the Moral Relevance View, as we alluded to above when we pointed out that empirical studies find that people take benevolent sexism to be more acceptable than hostile sexism. So if this view cannot be defended, we should be aware of not simply assuming the truth of this view when doing moral evaluations (for instance, of different kinds of sexism). Second, our investigation will show that prominent accounts of the wrongness of discrimination support the Moral Irrelevance View. This means that if our arguments are true and you want to hold on to the Moral Relevance View, you would need to find an alternative account of discrimination’s wrongness. That it speaks to the question of what makes discrimination wrongful is another significant upshot of the present investigation.

Before we move on, we would like to distinguish the question in which we are interested from related, but ultimately different, questions. First, stereotypes may be true or false (Beeghly 2021). For instance, suppose it were true that women are, on average, more intelligent than people from other groups. If so, the latter employer in the examples considered in the beginning may hold a true stereotype. An interesting question is whether it is worse to hold false, as opposed to true, stereotypes.Footnote 3 But our question is different. We are interested in whether the trait or skill attributed is generally considered favorable or unfavorable. So we want to hold fixed, when examining negative and positive stereotypes, the truth/falsity dimension. Second, a person being stereotyped might be either harmed or benefited by being stereotyped, e.g., not getting or getting the job. It is probably worse to discriminate based on a stereotype when doing so harms the discriminatee than when it benefits them. But this is not our focus. Again, we want to hold fixed, when examining negative and positive stereotypes, the harm/benefit dimension. Relatedly, it might be that, in general, it has worse consequences for a person to be the target of a negative stereotype than a positive stereotype. But that is compatible with our argument. What we say is that, all else equal (and thus holding harm constant), it is not morally worse to discriminate based on a negative stereotype than a positive stereotype. Think, again, of the cases with which we started, in which both Amanda (the person being negatively stereotyped) and Bella (the person being positively stereotyped) did not get the job precisely because they were stereotyped. Here the contingent harms are held constant. We want to argue that there is no non-contingent difference in moral wrongness between discriminating based on negative and positive stereotypes.Footnote 4

Exploring the Moral Relevance View and the Moral Irrelevance View

We will go about exploring the Moral Relevance View and the Moral Irrelevance View in the following way. If stereotype valence is to make a non-contingent moral difference to the moral evaluation of discrimination—such that the Moral Relevance View is true—we need an argument that explains what this difference is. Since we are interested in whether stereotype valence makes a difference to the moral evaluation of discrimination, it is natural to turn to arguments for why discrimination is wrong, when it is. This is what we will do in this section. To be clear, our analysis should not be read as suggesting that the authors behind these arguments themselves believe that there is reason to subscribe to the Moral Relevance View. They might or might not do so. Our discussion is intended as an investigation of what follows from their arguments.

Eidelson’s Account

So, let us explore whether different accounts of the wrongness of discrimination lend support to the Moral Relevance View or the Moral Irrelevance View.Footnote 5 A prominent account is Eidelson’s disrespect-based account. According to this view, discrimination is wrong when and because it is disrespectful. So, the relevant question for our purposes is whether it is more disrespectful to hold a negative than a positive stereotype. To answer this question, we must start by laying out Eidelson’s account. Building on Darwall (1977), the notion of respect that is central to Eidelson’s account is recognition respect. To show recognition respect for a person, one must'take seriously and weigh appropriately the fact that they are persons in deliberating about what to do' (Darwall 1977, p. 38; quoted in Eidelson 2015, p. 76). A person has two attributes, which one must respect to show recognition respect for their standing as a person. The first is that the person has moral value in themselves (and an equal value to other persons), and the second is that the person is an autonomous being (Eidelson 2015, p. 79).

The following interest thesis represents one central requirement to respecting a person’s equal moral value:

The Interest Thesis: To respect a person’s equal value relative to other persons one must value her interests equally with those of other persons, absent good reason for discounting them. (Eidelson 2015, p. 97)

Giving lower weight to Woman’s interests than to Man’s interests simply because she is a woman (and he is a man) is to fail the interest thesis and is therefore to disrespect her.

Does a person violate the interest thesis to a larger extent by negatively stereotyping than by positively stereotyping? To focus the discussion, let us continue with the example with which we started, namely the stupid/intelligent stereotypes. So, suppose Amanda and Bella are applying for a job at Employer’s company. And suppose, as in the original example, that the Employer, due to the stupid/intelligent stereotypes, decides not to hire any of them, but instead hires a candidate about whom they do not hold any stereotypes. If the interest that is to be respected in this case is their interest in getting the job, it seems that Employer fails the interest thesis both in relation to Amanda and Bella, and that to the same extent (see also Eidelson 2015, p. 114).

Perhaps it might be argued that one has a stronger interest in not being considered stupid qua group membership than in being considered intelligent qua group membership. If so, the Employer holding these stereotypes is more disrespectful to Amanda than Bella. But why would that be the case? We must remember that in these cases, the stereotype at work pertains to the candidates’ group membership. Presumably, the interest that must be respected in these cases is their interest in being considered and treated as an individual (the account focuses on recognition respect, recall).Footnote 6,Footnote 7 But, if so, then it is captured by the second part of Eidelson’s theory (to which we turn later in this section). Perhaps there is a contingent reason for why one might have a stronger interest in not being considered stupid qua group membership than in being considered intelligent qua group membership. Perhaps. But since we are exploring whether discriminating based on negative and positive stereotypes are unequally non-contingently wrong, that is neither here nor there. Thus, it seems that with respect to the interest thesis, Employer does equally wrong by discriminating based on the negative and the positive stereotype. After all, the candidates are treated similarly: they are denied the job because Employer holds a stereotype about them.

Another reason for thinking that negatively stereotyping is morally worse than positively stereotyping is differences in contempt,'understood as willful defiance of normative authority' (Eidelson 2015, p. 95). According to Eidelson (2015, p. 105),'[y]ou do not show contempt for something whenever you fail to respect it as you should. Rather, contempt has a more positive aspect. In particular, contempt seems to involve a refusal to respect something—a kind of defiance of what you at some level realize its significance to be'. Classical bigots willfully repudiate to attend to the interests of the discriminatee—they are not just inattentive to these interests. And according to Eidelson (2015, p. 106),'it is especially bad to deny or refuse to recognize people’s value as persons, as compared to simply failing to recognize it'. In view of Eidelson’s appeal to examples involving'textbook racists' and'bigots' (2015, p. 105), it seems that contempt usually involves negative stereotypes. Perhaps it is not possible to act contemptuously based on a positive stereotype. Does this mean that Eidelson’s theory, with the notion of contempt, supports the Moral Relevance View?

First, as Muñoz and Baron-Schmitt (forthcoming, p. 6) argue,'[t]o prove an Asymmetry […] it is not enough to establish the absence of a minimal pair', for example, by showing that discrimination based on negative stereotypes can involve contempt whereas discrimination based on positive stereotypes cannot. We must distinguish the Moral Relevance View from'Asymmetry of Possibilities' (cf. Muñoz and Baron-Schmitt (forthcoming), p. 6). In other words, it may be the case that:

For some S, A would contemptuously refuse to recognize B’s value as a person by discriminating against B based on a negative stereotype, but there is no possible S* in which A would contemptuously refuse to recognize B’s value as a person by discriminating against B based on a positive stereotype. (cf. ibid.)Footnote 8

If there is an Asymmetry of Possibilities, this does not disprove the Moral Irrelevance View. The Moral Irrelevance View says that if an agent can contemptuously refuse to recognize another person’s moral value through their discriminatory act based on a positive stereotype, then doing so is morally similar to contemptuously refusing to recognize another person’s moral value through negative stereotype discrimination (Muñoz and Baron-Schmitt forthcoming, p. 6).

Second, even if we assume that this is not true, we will argue that it is possible to act contemptuously based on a positive stereotype. Imagine for example an employer, who admires and generally thinks higher of women than men. But since the employer is malevolent, he finds pleasure in watching women fail precisely because he believes women are'higher beings'. For this reason, the employer lays down obstacles for their female employees.Footnote 9 It seems that this employer willfully repudiates to attend to the interests of the discriminatee, i.e., the employer acts out of contempt based on a positive stereotype. Compare this with a case where an employer acts in exactly similar ways, but now based on a negative stereotype. It seems far from clear that the former acts less wrongly than the latter; and if there is a difference, contempt does not explain it.

Now, let us turn to the second requirement of recognition respect. To respect a person as an autonomous being requires:

(i) taking evidence of her autonomous choices seriously in forming judgments about her and (ii) making judgments about her likely behavior in a way that respects her capacity, as an autonomous individual, to choose how to act for herself. (Eidelson 2015, p. 130)

The former—the character condition—is backward-looking and requires that one pays attention to how the person has exercised their autonomy in the past: their choice of commitments, values, personal projects, etc. The latter—the agency condition—is forward-looking and requires that one recognizes the person as an autonomous individual with the capacity to chart their own course, however (perhaps badly) they have chosen in the past.

If we focus, first, on the agency condition, it is hard to see why there would be a difference between being positively and negatively stereotyped in this sense. When Employer treats the candidates as if they are not autonomous beings—assuming that the candidates will behave in particular ways qua their group membership—they are treating both of them as if they are incapable of charting their own future course.

And the same goes for the character condition as long as we assume, as we should, that they are equally qualified for the position. Remember, the Moral Relevance View and the Moral Irrelevance View include an all else equal clause. Thus, to examine whether stereotype valence makes a difference to the moral evaluation of discrimination, all else equal, we need what Muñoz and Baron-Schmitt (forthcoming, p. 5) refer to as a minimal pair: two cases in which the only difference is that in one case the person holds a negative stereotype, and in the other the person holds a positive stereotype. If we were to assume that Amanda and Bella were unequally qualified due to their past choices, cf. the character condition, we would not have a minimal pair. And we would be unable to tell whether discriminating based on negative stereotypes is non-contingently morally worse than discriminating based on positive stereotypes.

Perhaps, it might be argued, you would be more willing to consent to being positively stereotyped than being negatively stereotyped. So the latter will violate your autonomy more than the former. If so, the agency condition will be violated more in the negative stereotype case than in the positive stereotype case. We have two responses to this argument. First, why would one be more willing to consent to being positively stereotyped than negatively stereotyped? If one cared about being treated as an individual whose autonomy is respected, it would seem that one should be equally unwilling to consent in the two cases. Second, even if it were true that, in many instances, a person would be more willing to consent to being positively stereotyped, this will not work in this context since, remember, we need a minimal pair. If we assume consent in one case, but not in the other, or if we assume less consent in one case than in the other, we no longer have a minimal pair. So we should assume that they would be equally (un)willing to consent to being positively and negatively stereotyped. Thus, we conclude that, according to Eidelson’s disrespect account, there is no non-contingent moral difference between negatively and positively stereotyping.Footnote 10

Arneson’s Animus

Arneson’s mental state-based account of the wrongness of discrimination emphasizes two wrong-making properties: animus and prejudice. According to Arneson (2006, p. 787),'wrongful discrimination occurs only when an agent treats a person identified as being of a certain type differently than she otherwise would have done from unwarranted animus or prejudice against persons of that type'. Arneson argues that discrimination from positive prejudice is wrongful for the same reason as discrimination from negative prejudice (in both cases, the discriminating agent fails to apply'reliable and epistemically nondefective rules and procedures' (Arneson 2006, p. 788; quoted by Eidelson 2015, p. 149, fn42)). Since his view of the stereotype property clearly does not challenge the Moral Irrelevance View, we will not discuss this property further. Of particular interest to our investigation in this paper is his focus on animus, which he defines as'hostility or, more broadly, a negative attitude, an aversion' (Arneson 2006, p. 787). Importantly, animus is defined as a negative attitude. So, perhaps this can provide a moral difference between negatively and positively stereotyping. After all, it might be argued that negatively stereotyping involves a negative attitude—and thus animus—whereas positively stereotyping does not. As Eidelson (2015, p. 112) puts it,'animus, as Arneson construes it, is fundamentally asymmetric or directional: partiality towards the interests of whites does not necessarily imply animus towards blacks, for instance'.

For two reasons, we do not think that Arneson’s argument supports the Moral Relevance View. First, why should it be worse to hold a negative attitude than a positive attitude, assuming that you hold the attitude qua the target’s group membership? After all, in both cases you ascribe properties to the individual irrespective of the individual’s actual properties. That is, it seems that there might be an equivalent of animus in the case in which you hold a positive belief based on the target’s group membership. We could call that posimus. A parallel might be helpful here. According to Hellman (2008), discrimination is wrong when and because it is demeaning. To demean is to express that another is'a lesser' (Hellman 2008, p. 29). But then there is also the case where you express that the other is'a morer'; as having higher status than they in fact have. We could call this ennobling others. Whereas to demean is to express lower status than the person in fact has, to ennoble is to express higher status than the person in fact has. It is not clear that the ennobled agent is treated less wrongly than the demeaned agent. After all, they are both treated differently than they ought to be treated. And the negative and positive trait they are attributed and treated on behalf of may be equally far away from how they ought to be treated given their moral status.Footnote 11 Similarly, it is not clear why animus is worse than posimus. In fact, this speaks to our final criticism of this proposal.

Second, there is a natural error theory for why we might believe that animus is worse than posimus. We might implicitly assume that the consequences for the targeted individual are worse in the negative case than in the positive case (i.e., that the former will be harmed in a way that the latter will not) (Moreau 2016).Footnote 12 But this is a contingent matter. And in the examples with which we are concerned, the consequences are identical in the negative and the positive case, namely that they do not get the job because they are being stereotyped.Footnote 13 For these reasons, we do not believe that appealing to animus can explain why there is a non-contingent moral difference between negatively and positively stereotyping.

Relational Equality

According to relational egalitarianism, a prominent view of justice, justice requires that people relate as equals (see, e.g., Anderson 1999; Lippert-Rasmussen 2018; Scheffler 2015). Discrimination is wrong, on this view, when, and because, it entails unequal relations.Footnote 14 Stereotyping is thus wrong when, and because, it entails unequal relations.Footnote 15 If negative stereotyping entails relational inequality in a way that positive stereotyping does not, then relational egalitarianism can provide a justification of the Moral Relevance View. And, arguably, a plausible one, considering that most people accept that relational egalitarianism at least provides a sufficient condition for injustice.Footnote 16

In fact, we must distinguish two different relational egalitarian views when it comes to stereotyping:

The Causal View: Discriminating based on stereotypes is wrong when, and because, it causes unequal relations.

The Constitutive View: Discriminating based on stereotypes is wrong when, and because, it is constitutive of unequal relations.Footnote 17

Whereas the Causal View points to the causal effects of discriminating based on stereotypes, the Constitutive View points to discriminating based on stereotypes being wrong when, and because, it is constitutive of unequal relations. So, if relational egalitarianism is to vindicate the Moral Relevance View, it must be the case that negatively stereotyping causes, or is constitutive of, unequal relations in a way that positively stereotyping is not.

To explore whether this is the case, we must start by clarifying what it takes to relate as equals. According to many relational egalitarians, X and Y relate as equals if, and only if, they (i) regard each other as equals, and (ii) treat each other as equals (see, e.g., Lippert-Rasmussen 2018, p. 117; Miller 1997, p. 224). Thus, if, say, Racist discriminates against Victim because they believe Victim is morally inferior due to their race, Racist fails to regard and treat Victim as an equal. And this is unjust according to relational egalitarianism.

With this in hand, let us start by analyzing negatively and positively stereotyping on the Causal View. Again, let us return to the example with which we started in which Amanda is negatively stereotyped (considered too stupid, because of group membership, to be qualified for the job) and Bella is positively stereotyped (considered too intelligent, because of group membership, to be qualified for the job), and the job goes to Carly who is not stereotyped by Employer. Clearly, qua negatively stereotyping Amanda, Employer might cause an unequal relationship between the two of them. After all, they treat Amanda worse than she ought to be treated, i.e., they deny her the job merely because they stereotype her. Moreover, it seems that Employer might also cause an unequal relation between Amanda and Carly. By treating Amanda as one who may be—who is fitting to be—stereotyped, and Carly as one who may not be, Employer may treat Amanda as an inferior in relation to Carly and thus cause an unequal relation in which Carly stands as a superior in relation to Amanda.

But, importantly, the same may be said in relation to Bella. Employer might cause an unequal relationship between themselves and Bella. After all, they treat Bella worse than she ought to be treated, i.e., they deny her the job merely because they stereotype her. And Employer treats Bella as one who is fit to be stereotyped, and Carly as one who is not, and may thus cause an unequal relationship between Bella and Carly. Indeed, it is hard to see that there should be any difference between the negative and positive stereotyping cases in this regard.

Perhaps one might respond that Employer treats Amanda more as an inferior than they treat Bella (although they treat both of them as inferior), by taking her to be stupid, rather than intelligent. And that, therefore, the negative stereotyping case is worse than the positive stereotyping case. This supports the Moral Relevance View.

But to see why this response fails,Footnote 18 it is useful to look to a reason which has been taken to ground relational egalitarianism, a reason which explains why it is unjust to relate as unequals. Lippert-Rasmussen (2018, p. 172, Ch. 7) suggests that fairness underlies relational egalitarianism:'it is unfair if people are differently situated if the fact that they are differently situated does not reflect their differential exercise of responsibility' (Lippert-Rasmussen 2018, p. 207). Assuming this view, it does not seem more unfair to deny Amanda the job than to deny Bella the job. They are both denied the job because they are being stereotyped which means that they are situated identically in relation to Carly; they are worse off than Carly in a way that does not reflect differential exercises of responsibility, and this is unfair. So if unfairness determines why the unequal relation is unjust, it seems that there is no non-contingent moral difference between negatively and positively stereotyping people according to the Causal View. This supports the Moral Irrelevance View.

Let us now turn to the Constitutive View. As Berker (2013, p. 346) explains,'X is an “upward” constitutive means to S [when] X’s occurrence, happening, or existence (partially or entirely) constitutes S’s obtaining'. To apply this to our discussion, we can say that stereotyping (X) is an upward constitutive means to an unequal relation (S) when the occurrence, happening, or existence of stereotyping (partially or entirely) constitutes an unequal relation obtaining. It seems that discriminating based on negative and positive stereotypes are symmetrical in this regard since the attitudes and treatments are relevantly identical in the two cases. As explained above, both Amanda and Bella are judged unworthy of the job, and are thus denied the job, because of being stereotyped. So if negative stereotyping is constitutive of an unequal relation, so is positive stereotyping. Another way of seeing this is through the following example:

Carlton: Bella works as a bouncer at a night club. She is instructed to admit at most a few Black persons per night. Bella herself is Black and working class. One night a group of wealthy private school boys arrive. Among them is Carlton, a Black student with a rich Belair background. Bella lets in all the rich white boys but sends Carlton away. (Schmidt 2022, p. 1378)

In introducing this example, Schmidt aims to show that how A (Bella) treats B (Carlton) might constitute relational inequalities between B (Carlton) and C (Carlton’s friends) (Schmidt 2022, p. 1389). This is constitutive of relational inequality between Carlton and his friends because Carlton is treated worse than his friends merely because of his race. Now, we can make the same point in our job cases. In the negative stereotyping case, how Employer treats Amanda is constitutive of relational inequality between Amanda and Carly (the one who gets the job) because Amanda is treated worse than Carly merely because of her group membership. And the same is true in the positive stereotyping case: how Employer treats Bella is constitutive of relational inequality between Bella and Carly (who gets the job) because Bella is treated worse than Carly merely because of her group membership. Moreover, it is constitutive of relational inequality to the same extent precisely because Amanda and Bella are treated the way they are for exactly the same reason, namely because of their group membership. There is no non-contingent moral difference between negatively and positively stereotyping according to the Constitutive View. Thus, this supports the Moral Irrelevance View. And it shows, more generally, that relational egalitarians should judge stereotype valence to be irrelevant to the moral evaluation of discrimination, all else equal.

Hellman’s Account

Another account of the wrongness of discrimination deserves attention. According to Hellman (2008), discrimination is wrong when and because it is demeaning. Hellman (2017, p. 102) suggests that:

‘Demeaning’ […] has two aspects: an expressive dimension and a power dimension. First, a demeaning action or policy expresses that a person or group is of lower status (the expressive dimension); and, second, the actor or institution expressing this meaning must have sufficient social power for this expression to have force (the power dimension).

Does this account support the Moral Relevance View? First, it seems clear that the power dimension of an act does not depend on whether the stereotype underlying the act is of a positive or negative kind. In other words, the power dimension should be held constant when discussing whether Hellman’s account supports the Moral Relevance View.

If we instead consider the expressive dimension, Hellman writes that'[t]he meaning the policy [or act] expresses is the objectively best interpretation of it in the particular culture, at the particular time' (Hellman 2017, p. 100). In our view, it seems likely that negatively stereotyping will more often be considered demeaning than positively stereotyping. For example, if we compare the negative stereotype of being stupid with the positive stereotype of being intelligent, it seems that, in most contexts, discrimination based on the negative stereotype is more likely to express that the discriminatee is inferior.

However, this does not preclude that one may express that a person is morally inferior when discriminating against them based on positive stereotypes. For example, benevolent sexism based on positive stereotypes can express that women are inferior. Imagine, in this context, an employer who refrains from making a female employee responsible for a major task because he thinks that women are dutiful and he therefore is afraid of overburdening the female employee. To be clear, it is not because he thinks that the female employee cannot handle the extra work (i.e., there is no latent negative stereotype at play), but because he thinks that it would be unfair to put too much work on the dutiful woman. It seems, however, that—in societies with a history of women having worse conditions for advancing in the labor market—this discriminatory behavior is likely to express that the female employee is inferior to male employees who are not spared from tasks by the employer in similar ways. Consider in this context that Hellman (2017, p. 105) stresses that her account of the wrongness of discrimination'denies the significance of intentions'. Even though the employer seems to have good intentions, the wrongness is determined by the social meaning of his discriminatory action (not his intention).Footnote 19 Accordingly, it seems that Hellman’s account of the wrongness of discrimination does not give us reason to support the Moral Relevance View.

It might be argued that stereotype valence is relevant in the sense that discrimination based on a positive stereotype does not have the capacity to express as much inferiority as discrimination based on a negative stereotype has. For example, discrimination based on hatred against black people may seem to express inferiority to a greater extent than any discrimination based on positive stereotypes about black people could ever express. However, as argued in relation to Eidelson’s account, the Moral Irrelevance View does not require the possibility of wronging A to the same extent through discrimination based on a positive stereotype as discrimination based on a negative stereotype. Instead, the Moral Irrelevance View says that if an agent (with sufficient power) can express that another person is morally inferior through their discriminatory act based on a positive stereotype, then doing so is morally like doing the same based on a negative stereotype (Muñoz and Baron-Schmitt, forthcoming, p. 6). In any case, why should benevolent sexism not be able to express as much inferiority as hostile sexism? Expressivist arguments are contingent arguments (Brennan and Jaworski 2015, p. 1057; Mogensen 2019, p. 91). Thus, we can easily imagine circumstances in which benevolent sexism expresses as much (or perhaps even more) inferiority as (than) hostile sexism.

Moreau’s Account

According to Moreau (2020), discrimination can be wrong for more than one reason. Discrimination may be wrong because it involves (i) unfair subordination; (ii) deliberative unfreedom; and/or (iii) denying people access to basic goods. We discussed subordination in section C, so we will set that aside. Before focusing on (ii), we will briefly illustrate why (iii) does not support the Moral Relevance View.

In her argument for the view that some of the wrongness of discrimination has to do with denying people basic goods (that is, goods the access to which is essential to participate fully and equally in society), Moreau (2020, pp. 144–145) asks us to consider the following Wackenheim case from 1999:

Wackenheim, who lives with the condition known as “dwarfism,” challenged bans on the sport of dwarf-tossing imposed by several municipalities in France. […] People with dwarfism don protective clothing and are thrown by the competitors onto air mattresses, with the winning competitor being the one who can throw the dwarf the farthest. […] Wackenheim argued that, as a person living with dwarfism, he had so few employment opportunities that dwarf-tossing was his one hope of having a steady job and a steady income, and that “dignity consists in having a job.” […] [I]n French society at the moment, dwarf-tossing is one of the only jobs available to people with dwarfism. So the opportunity to be employed in the sport of dwarf-tossing is, right now, a basic good for him. Without this opportunity, he cannot participate fully in French society; and so he cannot be, or be seen as, an equal.

Moreau argues that the bans might be justified all things considered if dwarf-tossing can be argued to involve wrongful subordination of people living with dwarfism. However, she argues that even if so,'there is a meaningful sense in which Wackenheim still has a residual moral objection to them' (Moreau 2020, p. 146). The bans on dwarf-tossing denies Wackenheim—and other people living with dwarfism—a basic good. It is clear that this conclusion, that bans on dwarf-tossing denies Wackenheim a basic good, follows irrespective of whether the policy-makers introduce the ban based on positive or negative stereotypes about people living with dwarfism. As Moreau’s example clearly illustrates, the wrongness of denying people access to a basic good does not pertain to the mental state or deliberation of the discriminating agent. So the basic goods part of Moreau’s account supports the Moral Irrelevance View.

Now, let us turn to deliberative freedom. According to Moreau,'this is the freedom to deliberate about one’s life, and to decide what to do in light of those deliberations, without having to treat certain personal traits (or other people’s assumptions about them) as costs, and without having to live one’s life with these traits always before one’s eyes' (Moreau 2020, p. 84). As is clear from this understanding, deliberative freedom involves that one is not imposed costs because of one’s personal social traits, but it also involves not having to think about these traits when deliberating about what to do. Now, consider the benevolent sexism case described above where an employer spares the female employee from significant tasks because he thinks that this might overburden the employee whom he considers to be dutiful qua her gender, i.e., he discriminates based on a positive stereotype. In this case, it seems that there is a relevant sense in which the female employee lacks deliberative freedom in a problematic way: the employer’s assumptions about her gender might involve costs for her in the sense that she is deprived of some opportunities for advancing in her job; at least, her gender has been'made an issue' (expression from Moreau 2020, p. 85) in a relevant sense.

According to Moreau, we only have a right to certain deliberative freedoms. Specifically, she suggests that autonomy, or respect for people'as beings who are equally capable of being autonomous' (p. 90), can help explain which deliberative freedoms people have a right to, i.e., which deliberative freedoms it would be wrong to deny people. This involves respecting people’s choices and letting people'live their lives in accordance with these choices, without being unfairly hindered by other people’s assumptions about who they are or who they ought to be' (p. 90). This underlying focus on autonomy seems to substantiate that the benevolent sexist employer not only restricts the deliberative freedom of the female employee; he restricts a deliberative freedom that the female employee has a right to. The employer’s positive stereotype about how women are closes off certain options from the female employee. The fact that the employer acts on a positive stereotype and not a negative stereotype does not seem to make any moral difference to whether the person’s autonomy is respected (cf. our discussion of Eidelson’s agency condition in Sect. 2A).

Objection

We have argued that according to prominent accounts of what makes discriminating wrong, stereotype valence is irrelevant to the moral evaluation of discrimination, all else equal. Some might think that this view has implausible implications. For example, the Moral Irrelevance View might be seen as suggesting that affirmative action based on negative stereotypes about the intended beneficiaries (e.g., that women have innate shortcomings making them less able to'compete on their own'), is not morally worse than affirmative action based on positive stereotypes (e.g., that women have particular skills that are beneficial for workplaces).Footnote 20 Intuitively, there seems to be a relevant difference between the two cases of affirmative action. Accordingly, it seems to be a counterexample to the Moral Irrelevance View if, as it seems, it suggests otherwise.

In response to this objection, we will stress the importance of the'all else equal' clause. It seems likely that our difference in intuitions pertaining to the two cases of affirmative action can be explained by factors that, for our purposes, should be held constant. For example, as we say in the introduction, the (in)accuracy of one’s stereotype might plausibly affect the wrongness of acting on this stereotype (see, e.g., Eidelson 2015, p. 174). It seems likely that this factor varies across the two cases, i.e., that only the positive stereotype is true. Another factor, which seems relevant to the wrongness of acts based on stereotypes, is the extent to which the intended beneficiaries of affirmative action consent to the measure. For example, affirmative action, which is pursued against the will of the intended beneficiaries, seems to show lack of recognition respect for the beneficiaries’ autonomy (cf. Eidelson 2015, chap. 6), or it might deny them a deliberative freedom that they have a right to. In the above case, if women consent to affirmative action based on the positive stereotype, but not to affirmative action based on the negative stereotype, this seems to imply that the latter is morally worse, but it does not show that the Moral Irrelevance View is false because the presence or absence of consent must be held constant across the two cases, i.e., we need a minimal pair.

In this context, if the intended beneficiaries do not consent to affirmative action across the two cases, another thing that varies is whether the policy is paternalistic.Footnote 21 Affirmative action based on the view that hiring women is good for the workplace does not seem to be paternalistic (the positive stereotype case), whereas affirmative action based on the view that hiring women is good for those women who are unable to get the job on their own because of innate shortcomings (the negative stereotype case) seems to be paternalistic.Footnote 22 It is a common view that paternalism is pro tanto wrongful because disrespectful of the autonomy or agency of the people interfered with (see, e.g., Eidelson 2015, p. 142; Enoch 2016; Feinberg 1986, p. 59; Groll 2012, p. 707; Shiffrin 2000, p. 220). Accordingly, this difference in paternalism between the two cases might explain differences in their wrongfulness (and in our intuitive reactions to them). However, nothing precludes that one can act with a positive stereotype and a paternalistic motive at the same time. Consider, for example, cases of benevolent sexism similar to the example of the employer who wants to protect the interests of the dutiful women. To test whether any differences in wrongness stem from the difference between employing positive and negative stereotypes, the paternalism factor should also be held constant.

In addition, it seems likely that affirmative action based on a positive stereotype is less harmful to the intended beneficiaries, e.g., because it has less stigmatizing consequences, than affirmative action based on negative stereotypes. The social meaning of the two policies may also vary, but, as pointed out above, what a policy expresses is a contingent matter, and we are interested in the non-contingent wrongness of stereotyping people.

So there are plausible error theories for why we may intuitively think that affirmative action based on negative stereotypes is worse than affirmative action based on positive stereotypes. But that does not challenge the Moral Irrelevance View.

Conclusion

One might intuitively think that it is non-contingently morally worse to believe of another that they are stupid qua their group membership than that they are intelligent qua their group membership. If that intuitive judgment is correct, that would support the Moral Relevance View according to which, all else equal, stereotype valence is relevant to the moral evaluation of discrimination. In this paper, we have challenged this Moral Relevance View. We have argued that prominent accounts of the wrongness of discrimination support the Moral Irrelevance View: a view according to which, all else equal, stereotype valence is irrelevant to the moral evaluation of discrimination. Some may still be leaning toward the Moral Relevance View. If so, they would need to find a new account of discrimination’s wrongness. This is one significant upshot of the present investigation.

Notes

Here, we borrow from Davis’s (2016, p. 486) understanding of positive stereotypes (which we also mention shortly; see also Khaitan 2015, p. 54). More generally, we may define stereotypes as'beliefs about an individual’s characteristics by inference from the characteristics statistically associated with groups of which the individual is a member' (Arneson 2006, p. 788, n28; see also Moreau 2016, pp. 284, 286).

Indirectly in the sense that we cannot totally exclude the possibility that there is a reason, different from those we discuss, which can ultimately justify the Moral Relevance View. But we do not think that this is particularly likely given the reasons we discuss, and since we believe that our arguments for why the different reasons do not support the Moral Relevance View apply, mutatis mutandis, to such potential reasons as well.

Some hold the view that discrimination is asymmetrical in the sense that it is impossible to discriminate against privileged groups. To not exclude such people from our investigation, we will only discuss examples involving stereotyping against marginalized groups in what follows. For those who do not have such an asymmetrical view, cases involving stereotyping of privileged groups will also be relevant. Here, the literature on testimonial injustice and credibility boosts may be helpful, e.g., a member of a privileged group, such as a white man, may be positively stereotyped such that their testimony is given more credit than the evidence suggests it should have (see, e.g., Davis 2016; Medina 2013). What we will argue in what follows also applies to stereotyping privileged people. We thank an anonymous reviewer for raising this issue.

Since our question is whether there is a non-contingent moral difference between negatively and positively stereotyping a person, we set aside the harm-based account of discrimination, most prominently put forward by Lippert-Rasmussen (2014; see also Rasmussen 2019), which explains discrimination’s wrongness by appealing to a contingent matter, namely harm.

This also speaks to the autonomy aspect of Eidelson’s view (to which we turn shortly).

We adapt their original formulation to the suggestion of contempt under consideration. Their original formulation of The Asymmetry of Possibilities says:'For some S: I would violate your rights by φ-ing you in S, but there is no possible S* in which I φ myself' (Muñoz and Baron-Schmitt forthcoming, p. 6).

This case is inspired by Lippert-Rasmussen’s (2006, pp. 182–184) case of a person performing cruel and unnecessary experiments on non-human animals, despite the person’s belief that non-human animals and humans have equal moral status. According to Eidelson (2015, p. 107), this person seems to act contemptuously.

This conclusion is in line with Eidelson’s assessment of the case by Arneson (2006, p. 788) of Antebellum abolitionists in the United States who held positive stereotypes about black slaves, but according to Eidelson still'may have failed to appreciate the autonomy of individual black people just as much as contemporary racists do. Like those who regard black people as prone to violence, those who took them to be loyal or compassionate by nature thereby demeaned their standing as autonomous agents' (Eidelson 2015, p. 149).

The Hellman example is only for illustrative purposes. We will discuss Hellman’s account of the wrongness of discrimination in Section 2D.

See Fourie (2022) for why, from the point of view of relational equality, it can be bad for you to be better off than others. This shows that we should not simply assume that it does not have negative consequences when one is treated better than one ought to be.

And there are other cases where being positively stereotyped is disadvantageous. Indeed, as Khaitan (2015, p. 54) explains,'even positive stereotypes which a society correctly views as positive can have disadvantageous effects—assumptions about women’s care-giving nature results in them being saddled with most of the child-rearing responsibilities while men can focus on their career advancement'.

Note that not all unequal relations may be unjust according to relational egalitarianism. Arguably, a plausible account of relational egalitarianism will distinguish between just and unjust unequal relations, given that some unequal relations do not seem unjust at all, e.g., unequal relations between teacher and student, and parent and child. Indeed, the pervasiveness problem precisely points out that relational egalitarians must provide a way of distinguishing just and unjust unequal relations (Scheffler 2005, pp. 17–18).

We adopt this distinction from Peña-Rangel (2022, p. 23) and modify it to our purposes. In fact, Peña-Rangel also points to a third view, namely an expressive view. We do not discuss this now, as we will discuss an expressive view when we, in section 2D, turn to Hellman’s view of the wrongness of discrimination.

We also suspect that this response is mostly driven by the implicit assumption that it is more harmful to be conceived as too stupid than too intelligent. But, remember, we need a minimal pair, so we hold constant the extent to which Amanda and Bella are being harmed by being stereotyped. So what we say here is consistent with it being, for contingent reasons, worse to be conceived as too stupid than too intelligent qua group membership.

Since Hellman'denies the significance of intentions' (Hellman 2017, p. 105), one might question why we consider her account to begin with. After all, whether or not the discrimination in question is based on a positive or negative stereotype has to do with the reasons for which the discriminating agent is acting. In response, we emphasize that Hellman’s view is complex in that it considers some internal mental states of the discriminating agent morally relevant to the wrongness of discrimination (ibid.). For this reason, it seems warranted to consider whether it, on her account, makes a morally relevant difference that the discriminating agent acts on a positive stereotype as opposed to a negative stereotype.

Paternalism may be understood as'unwelcome benevolent interference' (Grill 2018).

E.g., Bengtson and Pedersen (2024) argue that affirmative action is often paternalistic toward the intended beneficiaries who oppose the measures.

References

Anderson, Elizabeth. 1999. What is the point of equality? Ethics 109(2): 287–337.

Anderson, Elizabeth. 2010. The imperative of integration. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Arneson, Richard. 2006. What is wrongful discrimination? San Diego Law Review 43(4): 775–807.

Barreto, Manuella, and David M. Doyle. 2023. Benevolent and hostile sexism in a shifting global context. Nature Reviews Psychology 2: 98–111.

Beeghly, Erin. 2018. Failing to treat persons as individuals. Ergo 5: 687–711.

Beeghly, Erin. 2021. What’s wrong with stereotypes? The falsity hypothesis. Social Theory and Practice 47(1): 33–61.

Bengtson, Andreas, and Lyngby Pedersen. 2024. Affirmative action, paternalism, and respect. British Journal of Political Science 54 (2): 422–436.

Berker, Selim. 2013. Epistemic teleology and the separateness of propositions. The Philosophical Review 122(3): 337–393.

Brennan, Jason, and Peter Jaworski. 2015. Markets without symbolic limits. Ethics 125(4): 1053–1077.

Cahn, Stephen M. 2002. The affirmative action debate. New York: Routledge.

Darwall, Stephen L. 1977. Two kinds of respect. Ethics 88(1): 36–49.

Davis, Emmalon. 2016. Typecasts, tokens, and spokespersons: A case for credibility excess as testimonial injustice. Hypatia 31(3): 485–501.

Eidelson, Benjamin. 2013. Treating people as individuals. In Philosophical foundations of discrimination law, ed. Deborah Hellman and Sophia Moreau. 203–227. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eidelson, Benjamin. 2015. Discrimination and disrespect. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Enoch, David. 2016. II—What’s wrong with paternalism: Autonomy, belief, and action. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 116 (1): 21–48.

Feinberg, Joel. 1986. Harm to self. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fourie, Carina. 2022. How being better off is bad for you: Implications for distribution, relational equality, and an egalitarian ethos. In Autonomy and equality: Relational approaches. ed. Natalie Stoljar and Kristin Voigt. 169–194. New York: Routledge.

Glick, Peter, and Susan T. Fiske. 2001. An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist 56(2): 109–118.

Grill, Kalle. 2018. Paternalism by and towards groups. In The Routledge handbook of paternalism. ed. Jason Hanna and Kalle Grill. 46–58. Milton: Routledge.

Groll, Daniel. 2012. Paternalism, respect, and the will. Ethics 122(4): 692–720.

Hellman, Deborah. 2008. When is discrimination wrong? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hellman, Deborah. 2017. Discrimination and social meaning. In The Routledge handbook of the ethics of discrimination, ed. K. Lippert-Rasmussen. 91–107. London: Routledge.

Khaitan, Tarunabh. 2015. A theory of discrimination law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lippert-Rasmussen, Kasper. 2006. The badness of discrimination. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 9: 167–185.

Lippert-Rasmussen, Kasper. 2011. We are all different: Statistical discrimination and the right to be treated as an individual. The Journal of Ethics 15: 47–59.

Lippert-Rasmussen, Kasper. 2014. Born free and equal? A philosophical inquiry into the nature of discrimination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lippert-Rasmussen, Kasper. 2018. Relational egalitarianism: Living as equals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lippert-Rasmussen, Kasper. 2020. Making sense of affirmative action. New York: Oxford University Press.

Medina, José. 2013. The epistemology of resistance: Gender and racial oppression, epistemic injustice, and the social imagination. New York: Oxford University Press.

Miller, David. 1997. Equality and justice. Ratio 10(3): 222–237.

Mogensen, Andreas L. 2019. Meaning, medicine, and merit. Utilitas 32: 90–107.

Moles, Andres, and Tom Parr. 2019. Distributions and relations: A hybrid account. Political Studies 67(1): 132–148.

Moreau, Sophia. 2016. Equality rights and stereotypes. In Philosophical foundations of constitutional law, ed. David Dryzenhaus, and Malcolm Thorburn. 283–304. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moreau, Sophia. 2020. Faces of inequality: A theory of wrongful discrimination. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moya, Miguel, Peter Glick, Francisca Expósito, Soledad de Lemus, and Joshua Hart. 2007. It’s for your own good: benevolent sexism and women’s reactions to protectively justified restrictions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 33(10): 1421–1434.

Mulligan, Thomas. 2018. Justice and the meritocratic state. New York: Routledge.

Muñoz, Daniel and Nathaniel Baron-Schmitt. (forthcoming). Wronging oneself. Journal of Philosophy

Peña-Rangel, David. 2022. Political equality, plural voting, and the leveling down objection. Politics Philosophy & Economics 21(2): 122–164.

Rasmussen, Katharina Berndt. 2019. Harm and discrimination. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 22: 873–891.

Schauer, Frederick. 2003. Profiles, probabilities, and stereotypes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Scheffler, Samuel. 2005. Choice, circumstance and the value of equality. Politics Philosophy and Economics 4(4): 5–28.

Scheffler, Samuel. 2015. The practice of equality. In Social equality: On what it means to be equals, ed. C. Fourie, F. Schuppert, and I. Wallimann-Helmer. 21–44. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schmidt, Andreas T. 2022. From relational equality to personal responsibility. Philosophical Studies 179: 1373–1399.

Shiffrin, Seana V. 2000. Paternalism, unconscionability doctrine, and accommodation. Philosophy and Public Affairs 29(3): 205–250.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hugo Cossette-Lefebvre, Søren Flinch Midtgaard, Lauritz Aastrup Munch and two anonymous reviewers for Res Publica for helpful comments on previous versions of the article. We also thank the handling editor, Christie Hartley, for her editorial guidance. Finally, we thank the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF144) for funding.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Aarhus Universitet

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bengtson, A., Pedersen, V.M.L. Ambivalent Stereotypes. Res Publica (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-024-09670-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-024-09670-2