Abstract

This paper discusses a novel kind of argument for assessing the moral significance of acts of lying and misleading. It is based on considerations about valuable social norms that might be eroded by these actions, because these actions function as signals. Given that social norms can play an important role in supporting morality, individuals have a responsibility to preserve such norms and to prevent ‘cultural slopes’ that erode them. Depending on whether there are norms against lying, misleading, or both, and how likely it is that they might be eroded, these actions can thus have different moral significance. In cases in which the rule ‘do not lie’, as a relatively simple rule, functions as a ‘focal point’, acts of misleading are often morally preferable. In other words, in such cases the possibility of ‘cultural slopes’ can ground a context-dependent slippery slope argument for a moral difference between lying and misleading.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In ordinary moral life, we often draw a distinction between ‘lying’, in the sense of making an assertion one knows not to be true, often in order to deceive someone (see e.g. Feehan and Chisholm 1977, p. 152) and ‘misleading’ (in the sense of other strategies that lead another person to adopting a wrong belief, but without uttering a straightforward lie). Take the following situation: A, an employee, asks B, the team leader, about a position that she has advertised, because a friend of his wants to apply: ‘Is the position still open?’ B has already picked a candidate, but because the position is officially still open, she cannot tell him.Footnote 1 Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that B is morally justified in preferring her candidate, for example because this person is a very good fit and is in dire need of a job. In one scenario, she tells A ‘Sure, I haven’t decided yet’, which is a lie. In another scenario, she replies to A’s question in a misleading way, for example by saying: ‘Oh, I’m sure we’ll find a good person’. Let us assume that in both scenarios, A ends up with a wrong belief about the position still being open. Is there any reason for drawing a moral distinction between these scenarios?

In contrast to the commonsensical assumption that there might be a moral difference here, many philosophers have come to the conclusion that there is no morally relevant difference between lying and misleading, because both violate the basic prohibition of deception. Williams, for example, contrasts open lies with ‘conversational implicatures’ that send wrong messages to listeners, as when a person says ‘Someone opened your mail’, which is usually not taken to mean that it was the speaker herself (Williams 2002, pp. 96–97).Footnote 2 As Williams discusses, different thinkers, notably in the Catholic tradition, have argued for an exceptionless prohibition on lying. Confronted with cases in which lies seem to be justified, such as the often-cited ‘murderer-at-the-door’cases, they have argued for the permissibility of other forms of misleading (Williams 2002, pp. 100ff.). Williams is sceptical whether such a distinction can be defended: in many cases, he holds, ‘it makes no difference whether deceit takes the form of lying or of something else’ (Williams 2002, p. 108).

Jennifer Saul (2012, chap. IV) has recently summarised this debate and scrutinised various arguments that claim to establish a moral difference between lying and misleading. For example, some authors have suggested that in cases of misleading, the listener has to draw an inference, which gives her a more active, and hence more responsible, role in the communicative process. It has also been suggested that someone who misleads a listener often has to make greater efforts, which might be seen as an expression of circumspection. But Saul shows that these differences are not sufficient for grounding a moral distinction between lying and misleading: they can either be refuted by counterexamples, or they fail to live up to arguments about what does or does not make a moral difference in other contexts. She concludes that when one considers only the act in question, there is no morally relevant distinction between lying and misleading. Rather, we often mix up judgements about an agent’s character with judgements about the act (Saul 2012, pp. 86ff.).

In this paper I discuss a novel kind of argument for a possible difference in moral significance between acts of lying and misleading; it may not be the only explanation for such a difference, but it is one that can explain the intuition about the existence of such a difference in a number of cases. In moral theorising the rightness or wrongess of actions is often considered in isolation. I argue that we should consider an additional ingredient, which may come apart in different situations: the impact of these actions on social norms, which can vary from context to context. We often operate in social contexts in which actions function as signals about social norms. Therefore, actions can trigger ‘spirals’, a notion introduced by Jonathan Glover in order to describe ‘an influence on people’, which is then ‘repeated’ and snowballs into a larger effect (Glover 1975, pp. 179–180). One kind of spirals are shifts in social norms, or what I call ‘cultural slopes’. If the social norms in question are morally valuable, it can be morally required to do one’s bit to preserve them. Ceteris paribus, individuals therefore have a responsibility to take the effects of their actions on social norms into account—and this responsibility can, under certain circumstances, ground a distinction between lying and misleading.

This argument for the possibility of a moral difference between lying and misleading is an instance of a slippery slope argument. The discussion on slippery slopes has, so far, focussed on two kinds of slopes, logical and psychological ones.Footnote 3 Logical versions of slippery slope arguments concern problems of how to draw a conceptual line between different cases once a first, seemingly harmless, step ‘down the slope’ has been taken; psychological versions focus on the psychological effects of admitting exceptions from general rules. Cultural slopes are a third kind of slope: they concern the effects of individual actions on social norms and the possibility of their erosion.

I first discuss the relation between individual actions and social norms and the mechanics of cultural slopes, laying out the empirical assumptions of my argument. Next, I defend the moral relevance of social norms. Taken together, these two arguments imply a responsibility to take the effects of one’s actions on social norms into account. This means that the moral significance of acts of lying or misleading can be different. In cases in which there is a norm against lying, and there either is no norm against misleading, or such a norm exists but is less likely to be eroded, this provides a moral reason to prefer misleading over lying. The consideration of effects on social norms can also explain why for some cases we see a moral difference between acts of lying and misleading, while in others we see no moral difference.

Social Norms and Cultural Slopes

I use the term ‘social norms’ for describing norms that the members of a group consider valid for themselves and for other group members. Such norms can refer to actions and other forms of behaviour, e.g. bodily posture or dress codes, or to ways of speaking, e.g. the terms used to refer to certain events. One might want to describe the awareness of such norms as ‘common knowledge’—in the sense that I know that you know that I know etc.—but in many cases individuals do not ‘know’ about such norms in a conscious and explicit way. Rather, they have been socialised to accept them and obey them automatically, and only become aware of them if someone else does not obey them.Footnote 4 Social norms contribute to creating the various ‘cultures’ that one finds in different communities, organisations, or countries.

In what follows, I do not attempt to provide a systematic account of such social norms. Instead, I focus on three features that are relevant for understanding the phenomenon of ‘cultural slopes.’ The paradigmatic setting in which this phenomenon occurs are communities that are larger than face-to-face groups, but smaller and more interrelated than anonymous crowds. Typical examples are organisations such as companies or public bureaucracies, villages, or religious communities.Footnote 5 If the three features of adapative behaviour, fragility of norms, and mutual visibility are in place, there is a possibility of cultural slopes.

Adaptive Behaviour

Many individuals adapt their behaviour to what they perceive to be the prevailing social norms. Psychologist Gigerenzer (2010, p. 541) calls this the ‘imitate-your-peers’ heuristic. Without it, human culture would not be possible; evolutionary theorists argue that the development of the cognitive skills of the human race took place as a result of cultural transmission based on adaptive behaviour (e.g. Tomasello 2000). Adaptive behaviour is not per se morally desirable; there are many cases in which it would be morally wrong to use the ‘imitate-your-peers’ heuristic. In other situations, however, one has good reasons to imitate one’s peers, for example because they have more experience with a certain type of situation. But independently of whether and when it is morally justified to use this heuristic, adaptive behaviour is something we simply have to reckon with when interacting with other human beings.

Fragility

A second relevant feature of social norms is that they cannot be prevented from changing or being eroded by formal tools, e.g. by written codes. To be sure, certain norms can be written down—but all depends on how they are put into practice. Often, the social norms that individuals actually live by are at a great distance from the existing written codes, for better or worse. Moreover, some rules are too subtle to be captured in formal terms, or doing so would require using open-ended terms such as ‘appropriate’, which would in turn require interpretation. Written rules can exclude extreme cases, but they often cannot fully capture all that is at stake in the subtleties of human interaction.Footnote 6 And they cannot, on their own, prevent social norms from eroding, changing, or shifting.

Mutual Visibility

A third relevant feature of the communities in which individuals follow social norms, or fail to do so, is that individuals can observe one another’s behaviour. This distinguishes such communities from anonymous crowds—in which only some individuals are visible to others (more on this below)—and from settings in which individuals act in complete isolation from one another. Visibility makes adaptive behaviour possible in the first place; otherwise individuals would not know which norms to adapt to. Importantly, however, this visibility of actions often goes beyond the scope of those with whom one can explicitly discuss what one sees. In this respect, such communities differ from face-to-face contexts, e.g. families, in which there is mutual visibility, but there is also ample room for conversation. In somewhat larger communities, in contrast, it is usually not possible, if only for lack of time, to discuss everything people say or do. Thus, individuals often have to make guesses about another person’s intentions, or about the reasons for an emotional response.

Cultural Slopes

Taken together, these three features create constellations in which cultural slopes can occur. It is helpful to understand them along the lines of Bayes’s model of the updating of information in the face of new evidence. In processes of Bayesian updating, new pieces of information are seen as instances of an underlying fact or principle that add new evidence about it, and that can therefore be used to update one’s beliefs about it (Bayes 1764).Footnote 7 But in the case of social norms, there is no independent reality that stands behind, and informs, the individual instances. Rather, the reality ‘behind’ the instances is itself made up by these instances: by the behaviour and the interactions of the members of a community, who observe one another’s behaviour and change their own behaviour according to what they see others doing.

For illustration, consider an analogy from a different context.Footnote 8 In the first half of the twentieth century, some forgeries by Hans van Meegeren were mistaken for real Vermeers. Once this had happened to a number of van Meegerens, it happened more frequently, because the reference class of ‘Vermeers’ had changed: there were now more similarities with van Meegeren’s style of painting. In that case, however, there is an independent truth about the authorship by Vermeer or by van Meegeren, even if this truth may be difficult to come by. In the case of social norms, in contrast, there is no independent reality. Rather, the social norms are made up by the sum of individual actions, together with the reactions to this actions. For example, the way in which individuals treat one another, how much respect they show for one another, and how they react to deviant ways of treating each other, are the community’s social norms with regard to mutual respect.

To summarise the basic mechanism of cultural slopes: one steps on a cultural slope when an individual’s action, which is visible to others, functions as a signal that points in a certain direction, and others follow suit (because of adaptive behavior), reinforcing the tendency in this direction (ultimately undermining the norm, which is possible because of its fragility).

Often, the first steps of such a process are hardly perceptible, because they are small, single instances of deviance, which might be understood as new interpretations of the norm. By their very nature, social norms have to be adaptable to new circumstances. But each step into a certain direction can shift the perceived baseline, and so the next steps can go further, in a recursive process in which the same operation, iteratively applied to the result of previous instances, leads to a reinforcement of the shift (cf. also Ortmann 2010). In theory, even single actions can trigger massive shifts of social norms, for example by destroying a taboo that was previously taken to be in place.Footnote 9 Although Glover does not explicitly discuss shifts of social norms, they seem to be a paradigmatic instantiation of his notion of ‘spirals’. In fact, actions within communities that are visible to others often cannot avoid being signals about social norms, even if they are not intended as such.

To be sure, this is a highly stylised model; real-life processes are much more complex. Hence, it is also very difficult to predict how such processes play out. Some actions or decisions are highly visible or receive a lot of attention (e.g. actions by leaders of communities), hence it is more likely that they will have an impact on its social norms. Also, certain actions or decisions are seen as more central for the character of a community than others and hence watched more closely than others. Another category of actions that can have massive effects on social norms are actions that sharply deviate from existing norms. They are likely to trigger either strong counterreactions, or lasting changes in the fabric of the community’s social norms.

From a moral perspective, cultural spirals can be positive or negative, depending on the moral value of the prevalent norms and the direction of change. Shifting baselines can lead to moral improvements, e.g. when the members of a community gradually start to encourage one another to do the right thing. But they can also erode social norms that support individuals’ moral agency, and without which it may be very hard for them to do the right thing. In the next section, I look in more detail at the moral weight of social norms.

The Moral Weight of Social Norms

Social norms would have little relevance from a moral perspective if human beings were the kind of agents often presupposed, implicitly or explicitly, in moral theorising: sovereign agents who obey the voice of reason and are unaffected by the social contexts within which they act. This assumption is contradicted both by practical experience and by evidence from sociology and psychology. Human beings are indeed ‘social animals’: they feel a strong ‘need to belong’ (see e.g. Dijksterhuis and Bargh 2001, p. 33), and their behaviour is, to a large extent, shaped by their social environments. This does not mean that they should be understood as passive playthings of social forces. But in many situations, these forces do have an impact on them, and the best way to deal with them is to anticipate this impact.Footnote 10 Much could be said about the responsibility of individuals to question and scrutinise the social norms that they habitually obey, but this is not my current focus. What matters for the argument from cultural slopes is that we have to reckon with this influence of social norms on human behaviour, including our own.

The human tendency towards conformity, which explains the force of social norms, can be so strong that it even overrides one’s trust in one’s own sense of perception. When seven out of eight people confidently call the shorter one of two lines the longer one, maybe it is safer to follow their judgement? In Asch’s (1951) series of experiments, only 25% of the participants always insisted on their own correct perception, whereas 75% conformed to the opinion of the majority—which consisted of the experimenter’s collaborators who intentionally gave wrong answers—at least once. Psychologists have also collected evidence for conformity effects with regard to unethical behaviour: for example, when the members of one’s own social group cheat in an experiment, or even when they merely ask a question about cheating, this has a contagious effect on others members and increases the rate of cheating (Gino et al. 2011).

Many social norms concern dimensions of behaviour that are only marginally morally relevant, for example dress codes or rules of etiquette. In such cases, disregarding them is not morally troubling. But some social norms are such that we cannot be indifferent to them from a moral perspective. Some are directly morally harmful, for example by allowing, or even prescribing, the discrimination of minorities. Others cause moral harm in indirect ways, for example by licensing forms of behaviour that unnecessarily contribute to increasing CO2 emissions, thereby adding to the harm done by dangerous climate change. On the other hand, social norms can also be a positive resource for morality. Many social norms ban forms of behaviour that are not only against conventions, but also against morality, for example forms of behaviour that expose others to grave risks. They may also protect individuals against self-destructive behaviour, as when there is a norm against drinking and driving.

The Argument from Cultural Slopes and the Distinction Between Lying and Misleading

So far, I have argued for two claims: individual actions can have an effect on social norms because they can lead onto cultural slopes, and social norms can have moral weight because they can support moral behaviour and help prevent wrongdoing. We usually assume that individuals are responsible for their actions, and that they have a duty to help prevent wrongdoing. This implies that, ceteris paribus, they are also morally responsible for taking into account the effects of their actions on social norms. This may not be their most important or most obvious responsibility; in fact, it may sometimes be completely overshadowed by other duties or responsibilities. For example, in some cases—such as ‘murderer-at-the-door’ cases—the responsibility to prevent a murder completely overshadows considerations about the differential moral significance of lying or misleading. But arguably, there can be cases in which this responsibility tips the balance between two otherwise morally equivalent actions: if one of them risks leading onto a cultural slope that unravels a morally valuable social norm, and the other one does not, the second strategy is morally preferable.

As with all slippery slope arguments, much here depends here on the details of a concrete case. Slippery slope arguments are often rejected as fallacious, because there is no logical necessity that the first step leads to the following steps, i.e. that the slope really is slippery (see e.g. Walton 1992). Nonetheless, they can be valid if one can provide a plausible account of why and how the move from the first step onto the slope, and towards the morally problematic outcome at the end of the slope, happens.Footnote 11 The account of cultural slopes I have provided constitutes a way in which the ‘slipperiness’ of a slope can be shown. To see how it could ground a moral difference between acts of lying and misleading, we first need to consider the moral weight of the social norms in question, and then ask whether ‘cultural slopes’ might indeed happen.

The reason that these social norms—about lying and about misleading—are worthy of preservation is straightforward: we all benefit from norms of truthfulness being in place. But it can be tempting for individuals to free-ride, benefitting from the truth-telling of others but deviating from this norm when it furthers their own interests.Footnote 12 This is why it is helpful to have social norms in place, which individuals enforce by blaming or punishing violators.Footnote 13

Williams provides a genealogical account in which he shows that ‘the notions of truth and truthfulness’ can be ‘intellectually stabilized’ (Williams 2002, p. 3). They are needed in situations of ‘epistemic division of labour’, in which the members of a group rely on one another for acquiring true beliefs. Williams discusses the two virtues of ‘sincerity’ and ‘accuracy’, which he sees as responses to ‘what moralists might call temptation’, namely ‘fantasy’ and ‘wish’, i.e. the temptation not to make an effort to correctly report one’s knowledge to others (Williams 2002, p. 45). Sincerity means that one conveys one’s beliefs openly even if this is not in one’s own interest (Williams 2002, esp. p. 75). Accuracy means conveying precise information even when it is tempting to resort to imprecise information because the acquisition of precise information requires an ‘investigative investment’ and is therefore costlier (Williams 2002, p. 87 and chap. 6). Together they lead to the notion of ‘trustworthiness’ (Williams 2002, p. 89).

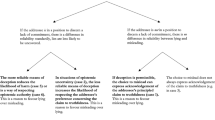

As mentioned earlier, Williams does not think that lying and misleading are of different moral weight. In what follows, I assume that we can draw a conceptual distinction between these types of actions, and that we can, hence conceptually distinguish between a social norm against lying and one against misleading. Now, in what cases could considerations about the preservation of social norms make a difference that tips the balance between lying and misleading? We need to distinguish various scenarios.

A first question is whether or not there is any risk of a social norm, against lying or misleading or both, being eroded. This is not the case if the action in question is not visible to anyone, for example when it happens towards a dying person on their deathbed, with no one else around (of course, lying or misleading might be wrong for other reasons, but by assumption, we are talking about a morally justified case, e.g. an act that helps preserve the peace of mind of the dying personFootnote 14). For such cases, ‘cultural slopes’ cannot make a difference to the moral significance of these actions. In contrast, actions visible to others in communities, as well as public actions, especially those by highly visible figures, are candidates for actions that contribute to an erosion of social norms.

Now, the fact that they contribute to the erosion of social norms can make acts of both lying and misleading morally worse. Think, for example, about the blatant lies by high-profile politicians in some countries: they seem to have contributed to a general perception that one cannot any longer expect truthfulness in political discourse (more on this below). This is in itself noteworthy, but for the purpose of this paper a different question needs to be addressed: can there be situations in which there is a moral difference between lying and misleading? I will first consider situations in which there is only a norm against lying, but not against misleading, and then situations in which there are norms against both, but there might be reasons to think that one is more fragile than the other, and therefore the risk of erosion is greater for one than the other.

Arguably, there are certain social situations in which there is a social norm against lying, but none against misleading. This can be the case in certain adversarial situations, e.g. among buyers and sellers in business-to-business markets or financial markets (whether or not this should be so is another question; I simply take these stylised sociological facts as given). In some such markets, everyone knows that one runs a risk of being misled, and this is accepted because the responsibility for not being misled is seen as lying with the other party. But we can imagine that there continues to be a taboo on lies, which might be connected to the fact that there is also a legal norm against lying. The social norm against lying could then be eroded by an act of lying, but there is no comparable risk when an act of misleading happens, because there is, by assumption, no social norm that could be eroded. Hence, other things being equal, misleading has fewer negative effects, and is therefore morally preferable to lying. This is thus a first instance in which the consideration not to erode a social norm would introduce a difference between the moral evaluation of an act of lying vs. misleading.

Could we also imagine a situation in which there is a norm against misleading, but none against lying? That seems unlikely, because individuals could then simply turn to blatant lies whenever they want to mislead someone. There may be cases in which individuals are particularly trusting, and which misleading would be particularly insidious because it makes them complicit in their own deception (see Rees 2014 for a discussion). But in many cases, the norm against lies is stronger, as can be seen in cases in which a speaker first tries to mislead a hearer, but when the hearer insists on precise statements, resorts to a lie (cf. also Rees 2014, p. 63 for such an example). Such cases can be read as the speaker attempting to ‘get away’ without violating the social norm at first, and only taking this step when in a tight corner.

What we also see are situations in which lying is formally banned (e.g. by the law or by organisational rules), but there is no explicit formal rule against misleading. These are typical situations in which questions about the conceptual line between lying and misleading are controversially discussed (think, for example, about a case quoted by Egré and Icard 2018, p. 355 and p. 367, of the Ferrero company claiming, in advertising, that chocolate was ‘healthy’). Policing that boundary is important, because there could be similar processes of erosion (with less and less cases considered lies, and hence being sanctioned). But this question is different from the one addressed here, namely whether the risk of norm erosion could make a moral difference for the differential moral evaluation of lying versus misleading.

In many contexts, there are in fact social norms against lying and misleading. Are there any reasons to think that we might nonetheless want to distinguish the cases, based on considerations about social norm erosion? It might be said that the norm against lying is simply weightier, or more central to our sense of what morality is all about, than a norm against misleading—but this would beg the question, because it would require an independent argument about what constitutes the moral difference between lying and misleading. But there is a second possibility, which can provide an independent argument: sometimes, certain norms are more likely to be eroded than others, not because of their content but because of their structure. There could thus be a greater likelihood to erode one norm than another. Could this offer a reason for moral differentiation?

One candidate for such an explanation is that some norms are more clear-cut than others. As Kreps has emphasised in a discussion about organisational cultures, such cultures need clear, easy-to-memorise markers, which can function as ‘focal points’ (Kreps 1990, pp. 126–127).Footnote 15 So the question would be whether the norm ‘do not lie’ can serve as a better ‘focal point’ than the norm ‘do not mislead’.Footnote 16

Now, the norm ‘do not lie’ seems simple and straightforward. It is taught to young children, and it is included in many moral codes. Nonetheless, philosophers have recently provided various arguments for thinking that this rule is in fact more complicated, because the definition of a lie is more complicated. For example, what a speaker says is not always either clearly true or clearly false; there can also be grades of beliefs, which make the concept of a lie itself a graded concept (e.g. Marsili 2014, 2018; on the degrees of beliefs of the recipient see Krauss 2017, but see also critically Benton 2018). Another question is whether or not the hearer can actually expect to hear a true statement from the potential liar, which is not the case in all social contexts, so that some false statements might not count as lies (see Carson 2006).

However, one can grant these points, and yet argue that the norm ‘do not mislead’ is even less clear-cut. Arguably, these considerations of what makes the concept of a lie less straightforward than is often assumed also apply to cases of misleading (e.g. there can also be grades of certainty by the speaker and the hearer, and there can also be contexts in which hearers cannot expect non-misleading statements, etc.). But for cases of misleading, there are even more factors to consider.

In cases of misleading, the role of the hearer is more complex than in case of lying. Many cases of misleading consist in ways of not quite answering a question or not quite making a statement, but doing it in a way that makes the hearer think that the question has been answered, or a statement has been made. But often it would be possible for the hearer to insist on a precise statement. Sometimes he or she might be inattentive, or not care enough about the truth of the statement to insist; sometimes norms of politeness or lack of time may be obstacles to insisting on precision. But in any case, there are open questions about the role of the hearer and his or her co-responsibility for the success of the act of misleading. These questions are often far more complex than the relation between the speaker and the hearer in the case of lies.

Relatedly, it may also be more difficult to judge whether a statement was an act of misleading or not. Often, it would be necessary to know the precise intentions of the speaker to identify an act of misleading and to differentiate it from other communicative mishaps. Instead of being an act of misleading, the deception could, for example, be down to a lack of attention, on the part of the speaker, because he or she did not answer a question very precisely (note that this is a typical pretext when speakers are caught in attempts to mislead!). Also, it is not always clear how the blame for the final result—the hearer ending up with a wrong belief—should be divided between the speaker and the hearer; in many cases the hearer might, after all, insist on a precise answer. Given these ambiguities, hearers may also be more hesistant to confront a speaker when they suspect that they might have been misled than when they have been lied to. For all these reasons, the social norm against misleading is more difficult to stabilise, and hence less likely to be a strong focal point, than the social norm against lying.

Thus, if one can choose between a lie—which threatens to unravel a norm that serves as a clearer focal point—and an act of misleading—which might somewhat shift the norm against misleading, but it is less clear whether or not it will do so—then this constitutes an argument in favour of choosing the act of misleading as the lesser evil. To be sure, this argument certainly does not apply to all contexts, and its strength depends on the details of specific cases, which are difficult to assess in the abstract. There might also be cases in which the erosion of both kinds of social norms is equally likely, and any difference in moral significance would have to be explained by different arguments. But it is plausible that there can be cases in which the argument can explain our intuitions about morally relevant differences.Footnote 17

One might ask, however, why it matters how one’s credibility is affected by an act of lying or misleading. Arguably, the weight of such considerations depends on the social context within which the consequences of a lie or a case of misleading play out. In face-to-face contexts, a liar or someone who misleads someone else can be directly confronted; they can then explain their reasons, which the other party can accept or not; ideally, the relationship can be repaired and credibility can be restored. In other contexts, in contrast, for example when anonymous strangers interact, there is no extended or repeated interaction. Hence, considerations about the damage in credibility someone incurs are of little practical relevance.

In contexts in which social norms matter, and in which there is a risk of cultural slopes, things look different. In them, individuals can observe one another’s behaviour within a scope that is larger than the scope of those with whom they directly interact and whom they could ask about their motives. In addition, it is often difficult or impossible to confront others if one suspects them of having lied or misled, whether for lack of time or because they stand in a position of power that makes it too risky to address the issue. But there is nonetheless visible, direct, and often repeated, interaction, between individuals—and hence the reputation of individuals as credible or not matters. The difference in the ways in which lies or acts of misleading damage one’s credibility is thus of particular importance in such contexts.

Webber’s argument is thus similar to the one from social norms: ‘credibility in assertion’ of an individual can be understood as a reliable expectation, for a series of future instances, that this person will not lie. The social norm not to lie is distributed across the different members, rather than across a series of future instances. Thus, while Webber remains in the individualistic model that has traditionally been assumed in the debate, my account widens the focus to take into account the social context. Depending on the case at hand, either one or the other focus may play a greater role. But as I have made clear above, Webber’s very assumption that ‘credibility in assertion’ is worth preserving implicitly refers to the social embeddedness of the act in question.

Let me now apply these arguments to a few examples. First, take the case described in the Introduction, in which a team leader can choose between an open lie and an act of misleading. The intuition that a blatant lie is worse, in that situation, might stem from the fact that a lie might erode the social norm not to lie in that team (while some forms of misleading might be considered acceptable). It is especially because team leaders have a highly visible role, as role models to whom all team members turn in order to see what kind of behaviour is accepted or not, that their actions play an important role as signals, and hence can have a potentially strong effect on social norms.

This high visibility is probably also why acts of lying or misleading by world leaders have received a lot of attention. Take the difference between US presidents Bill Clinton—who went to great lengths and exploited various forms of semantic vagueness in order to avoid a blatant lie and yet not admit the nature of his relations with Monica Lewinksy (see Egré and Icard 2018, pp. 365–366, for a discussion)—and Donald Trump, who is constantly caught in blatant lies.Footnote 18 Arguably, Trump thereby broke the taboo that blatant lies are not supposed to be part of political discourse. One might, however, object to that example that neither of them was justified in lying or misleading, whereas I had started the discussion from the assumption that we see cases of morally justified forms of deception. So it might be said that unravelling the social norm against lying makes Trump’s behaviour even worse, but if he were committing acts of misleading at a comparable rate, it would not make a huge difference.

Let me therefore add another example, in which the lie or act of misleading is indeed justified, and by which the differential proneness to erosion of the two norms can be illustrated. Take the case of an extended family, which is sort of harmonious, sort of not. Some people like each other more than others, some are envious of others, there are some sore points that some people would rather not touch again, some think that others have horrible political opinions (e.g. supporting someone who has completely eroded the taboo on lying in public), etc. To navigate family relations, some degree of strategic communication is unavoidable: some degree of misleading has to happen, and is generally accepted as a necessity to maintain family harmony. But let us assume that so far, there has also been a social norm against blatant lies.

If a family member is asked ‘What do you think about uncle Edward’s political views?’, they can choose between a blatant lie and an act of misleading. The latter prevents unravelling a social norm that is very valuable for maintaining the social fabric of the family. Acts of misleading at least preserve the trust in the assertions individuals make, even though it may undermine the trust in the implications of their assertions. In order to communicate within the family, it matters a lot that one can at least rely on assertions. One can probably maintain a modus vivendi (though arguably a fragile one) in which some acts of misleading happen, whereas open lies would be so destructive for the social ties among family members that the social fabric would unravel.

One might hold, against my proposal that acts of misleading are for these reasons often preferable, that such acts can sometimes be particularly malicious, precisely because they avoid a lie, and hence also avoid the blame that usually follows when a lie is discovered. But I would suggest that in such cases, the additional moral weight stems from the maliciousness, not from the act as such.Footnote 19 Sometimes, individuals might not be able to find non-malicious ways of misleading, and hence a lie is the only option they can resort to. But if they have a chance to come up with a non-malicious version of an act of misleading that avoids a blatant lie, then, in situations in which social norm erosion is a possibility, this is the morally preferable path.

Thus, the argument from cultural slopes does not amount to an outright ban on lies. It is not relevant for all contexts, and where it is relevant, it can be outweighed by other, more important, moral considerations. But everything else being equal, where individuals can choose between an action that risks eroding morally valuable social norms, and one that avoids such effects, they should choose the latter.

Conclusion

In this paper I have presented an argument from cultural slopes that explains why there can sometimes be a moral difference between lying and misleading, namely when they happen in contexts in which the former, but not the latter, risks eroding a valuable social norm. The crucial question is whether there are norms against lying and misleading, or only a norm against lying, and if both exist, how likely it is that each might be eroded by a violation.

This argument has not yet been considered in the debate about lying and misleading, probably because the focus has been on the acts of lying and misleading considered in isolation, without attention to the social context. Nor have cultural slopes been considered in the debate about slippery slopes. This may be a result of an overly rational picture of human beings as autonomous agents who are not influenced by social norms.

Flattering as this picture may be, there are good reasons to think that it is not accurate: human beings are social animals, and social norms matter greatly for how they behave. Ceteris paribus, we have a responsibility not to undermine morally valuable social norms that support us in doing the right thing. This is why there is a morally relevant difference between the different scenarios outlined in the Introduction: if B openly lies to A, this is likely to erode the social norm against lying in her team than if she evades his question. The intuition that these forms of behaviour are different is justified, but not because of the acts themselves, but because by avoiding an open lie, B avoids sending a signal that could lead to a cultural slope that undermines the norm not to lie.

Notes

We can assume that she also cannot tell him that she cannot tell him, because that would rouse his suspicion.

The term ‘conversational implicature’ is taken from Grice. Cf. also Saul (2012), pp. 75ff., on non-linguistic behaviour that is used to mislead, for example packing a suitcase to imply that one is going on a journey, an example going back to Kant.

See Rachels (1986, p. 172) for this distinction. Notable contributions to the debate about ‘slippery slopes’ include van de Burg (1991), who argues that the force of slippery slope arguments is strongest in law, and less strong in ‘critical morality’ and ‘positive morality’. Slippery slope arguments have often been used in the context of medical ethics and in particular in the debate about abortion, where the difficulty of drawing a line between a zygote and a person has been used as an argument against any form of abortion (see e.g. Wreen 2004). Walton (1992) focusses on the role of slippery-slope arguments in deliberation.

As Hartman describes this lack of awareness: ‘The important messages are often not stated explicitly: even people most influential in keeping the cultural flame may be unable to state the rules, for the same reason fish do not feel wet’ (Hartman 1996, p. 149).

With regard to certain forms of behaviour and certain social norms, online communities might also exhibit the relevant features.

The philosophical debate about rule-following, initiated by Wittgenstein (1958) and expanded by Kripke (1982), here has a practical equivalent. This debate turned around the question of whether seemingly clear-cut rules, such as ‘add 2’, can ever fully determine human behaviour, or whether they depend on the human practices that collectively define that this rule implies ‘1002, 1004, 1006, …’ (Wittgenstein 1958, p. 201). Even seemingly clear rules such as the mathematical rule ‘add 2' might be understood as changing their nature once they reach a certain threshold, e.g. 1000, or as including implicit exceptions for specific cases. But whether or not one accepts the premises of this apparent paradox with regard to mathematical rules, the vagueness of many non-mathematical rules, including social norms, can create practical challenges. Everyday rules such as ‘wear appropriate clothing at a funeral’ require interpretation: what counts as ‘appropriate’ depends on circumstances and can shift over time, and the openness of the term means that one cannot anticipate all applications to future cases.

On the falling of taboos as one form in which slopes can be slippery see also Woods (2002). Woods’s focus, however, is on what he calls ‘dialectical fatigue’ (Woods 2002, p. 121), i.e. the inability to find arguments for defending distinctions once a certain line has been crossed. This is a ‘logical’ version of a slippery-slope argument, not a ‘cultural’ one.

One way of capturing this issue is in terms of what Kahneman (2011) has, metaphorically, described as ‘system 1′ versus ‘system 2′: ‘system 1′ ‘operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control’. ‘System 2,’ in contrast, is ‘slower, conscious, effortful, explicit, and more logical’ (Kahneman 2011, p. 20). We can scrutinise system 1 behaviour from a system 2 perspective and take steps to prevent moral mistakes that we might make when operating in system 1.

Of course, if the free-riding went so far that individuals could not at all rely on linguistic utterances any more, then the very point of communication would be undermined. I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

Thus, those who have the intuition that there is nonetheless a morally relevant difference between lying and misleading (assuming that the deceit in general is justified) to a dying person have to draw on other explanations for the difference in moral significance. I here remain agnostic on this possibility, but want to flag that my argument cannot explain a difference in such scenarios.

He draws on Schelling’s path-breaking work on ‘focal points’.

Admittedly, the social norm ‘Do not deceive’ might be even clearer, and hence a better focal point, than either ‘Do not lie’ or ‘Do not mislead’ (I thank an anonymous reviewer for pressing that point). But by assumption, we are dealing with cases in which the deception is morally justified overall. However, a similar argument about norm erosion could be made to say that deception should be avoided whenever possible, and this argument might sometimes tip the balance between the permissibility and the impermissibility of an act of deception.

The role of cultural slopes can be connected to an argument recently brought forward by Webber. He argues that acts of lying and misleading have different effects on someone’s standing as a trustworthy informant. If a person misleads someone else, her trustworthiness with regard to the implicatures of her statements is damaged, but her trustworthiness with regard to the truth-value of statements—what Webber (2014) calls ‘credibility in assertion’—is kept intact. A lie, in contrast, damages her credibility both with regard to assertions and with regard to implicatures: the person becomes unreliable as a partner in conversation in a broader sense. Webber hastens to add that this does not mean that every instance of lying is morally worse than every instance of misleading (Webber 2014, p. 658). But he insists that there is a relevant difference.

See the Wikipedia page https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veracity_of_statements_by_Donald_Trump (last accessed March 30th, 2020).

In fact, for non-malicious forms of ‘misleading’ ‘circumventing’ might be the better term. But because the debate has been framed in terms of ‘lying’ versus ‘misleading,’ I stick to this terminology.

References

Asch, Solomon E. 1951. Effects of Group Pressure on the Modification and Distortion of Judgments. In Groups, Leadership and Men, ed. H. Guetzkow, 177–190. Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Press.

Bayes, Thames. 1764. An Essay Toward Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 53: 370–418.

Benton, Matthew Aaron. 2018. Lying, Accuracy and Credence. Analysis 78 (2): 195–198.

Carson, Thomas L. 2006. The Definition of Lying. Nous 2: 284–306.

Dijksterhuis, Ap, and John A. Bargh. 2001. The Perception-Behavior Expressway: Automatic Effects on Social Perception on Social Behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 33: 1–40.

Egré, Paul, and Benjamin Icard. 2018. Lying and Vagueness. In The Oxford Handbook of Lying, ed. Jörg Meibauer, 354–369. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feehan, Thomas, and Roderick Chisholm. 1977. The Intent to Deceive. The Journal of Philosophy 74: 143–159.

Fehr, Ernst, and Urs Fischbacher. 2004. Social Norms and Human Cooperation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 8 (4): 185–190.

Fehr, Ernst, and Simon Gächter. 2002. Altruistic Punishment in Humans. Nature 415: 137.

Gigerenzer, Gerd. 2010. Moral Satisficing: Rethinking Moral Behavior as Bounded Rationality. Topics in Cognitive Science 2: 528–554.

Gino, Francesca, Maurice E. Schweitzer, Nicole L. Mead, and Dan Ariely. 2011. Unable to Resist Temptation: How Self-Control Depletion Promotes Unethical Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 115 (2): 191–203.

Gintis, Herbert, Eric Alden Smith, and Samuel Bowles. 2001. Costly Signaling and Cooperation. Journal of Theoretical Biology 213 (1): 103–119.

Glover, Jonathan. 1975. It Makes no Difference Whether or Not I Do It. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary 49: 171–190.

Goodman, Nelson. 1976. Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing.

Haidt, Jonathan, and Craig Joseph. 2004. Intuitive Ethics: How Innately Prepared Intuitions Generate Culturally Variable Virtues. Daedalus 133 (4): 55–66.

Hahn, Ulrike, and Mike Oaksford. 2006. A Bayesian Approach to Informal Argument Fallacies. Synthese 152 (2): 207–236.

Hartman, Edwin M. 1996. Organizational Ethics and the Good Life. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Joyce, James. 2008. Bayes’ Theorem. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2008 edn), ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/bayes-theorem/.

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kreps, David M. 1990. Cooperate Culture and Economic Theory. In Perspectives on Positive Political Economy, ed. J. Alt and K. Shepsle, 90–143. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krauss, Sam Fox. 2017. Lying, Risk and Accuracy. Analysis 73: 651–659.

Kripke, Saul. 1982. Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lode, Eric. 1999. Slippery Slope Arguments and Legal Reasoning. California Law Review 87: 1469–1543.

Marsili, Neri. 2014. Lying as a Scalar Phenomenon. In Certainty-Uncertainty—and the Attitudinal Space in Between, ed. Sibilla Cantarini, Werner Abraham, and Elisabeth Leiss, 153–173. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Marsili, Neri. 2018. Lying and Certainty. In The Oxford Handbook of Lying, ed. Jörg Meibauer, 169–182. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ortmann, Günther. 2010. Organisation und Moral Die dunkle Seite. Weilerswist: Velbrück Wissenschaft.

Rachels, James. 1986. The End of Life. Euthanasia and Morality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rakoczy, Hannes, Felix Warneken, and Michael Tomasello. 2008. The Sources of Normativity: Young Children’s Awareness of the Normative Structure of Games. Developmental Psychology 44 (3): 875–881.

Rees, Clea F. 2014. Better Lie! Analysis 74 (1): 59–64.

Saul, Jennifer M. 2012. Lying, Misleading, and What is Said: An Exploration in Philosophy of Language and in Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Strudler, Alan. 2010. The Distinctive Wrong of Lying. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 13: 171–179.

Tomasello, Michael. 2000. The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

van der Burg, Wibren. 1991. The Slippery Slope Argument. Ethics 102 (1): 42–65.

Volokh, Eugene. 2003. The Mechanisms of Slippery Slope. Harvard Law Review 116: 1026–1137.

Walton, Douglas. 1992. Slippery Slope Arguments. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Webber, Jonathan. 2014. Liar! Analysis 73 (4): 651–659.

Williams, Bernard. 1995. Which slopes are slippery? In Making Sense of Humanity. And Other Philosophical Papers 1982–1992, ed. Bernard Williams, 213–223. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, Bernard. 2002. Truth and Truthfulness. An Essay in Genealogy. Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1958. Philosophical Investigations. Transl. by G. E. M. Anscombe. 2nd edn. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Woods, John. 2000. Slippery Slopes and Collapsing Taboos. Argumentation 14: 107–134.

Wreen, Michael J. 2004. The Standing is Slippery. Philosophy 79 (310): 553–572.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank audiences at the universities of Glasgow, Munich, and Leipzig, as well as the anonymous reviewers of Res Publica, for very valuable comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Herzog, L. Lying, Misleading, and the Argument from Cultural Slopes. Res Publica 27, 77–93 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-020-09462-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-020-09462-4