Abstract

Developments in fields as diverse as biotechnology, animal cognition, and computer science have cast serious doubt on the common belief that human beings are unique and that only they should have dignity and basic rights. A movement referred to as ‘new dignitarianism’ has recently reclaimed human dignity to fend off the threats to human uniqueness that it perceives to arise from these developments. This ‘new’ dignitarianism, however, is not new at all. Drawing on a debate between two Enlightenment philosophers, this article shows that dignitarianism has already surfaced in the eighteenth century as the negative image of another movement: naturalism. Building on this historical account, I propose to understand dignitarianism and naturalism as opposing ideal-types on a normative spectrum. Doing so allows us to see a thus-far neglected problem, which I call the Zero-Sum Problem: any gains a concrete theory makes by approximating one ideal-type, it loses by moving away from the other. I end by showing how accepting this fact is a first step to more practically viable theories that attempt to find a middle ground between the two ideal-types.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent times have witnessed a resurrection of human dignity. In a world in which scientific advances have opened up new possibilities of altering the human being, in which newly discovered cognitive capacities of nonhuman animals reveal remarkable similarities between them and their human brethren, and in which artificial intelligences (AIs) are beginning to surpass humans in domains formerly monopolised by humanity, the essence of what it means to be human seems to be shaken to its very foundations. Adding to the instability of the situation, philosophers and lawyers are debating what moral and legal treatment we owe to biotechnologically enhanced humans and whether animals and AIs should receive similar consideration.

In an effort to counter these developments, a movement referred to as ‘new dignitarianism’ has emerged (Caulfield and Brownsword 2006, p. 72). While motivated by a range of different religious and philosophical views, the ‘new dignitarians’ are united in their enlisting of the concept of human dignity for the purpose of countering what they perceive to be threats to the special moral and legal status of humanity (see Brownsword 2012, p. 19). George Kateb’s work is a case in point. Taking issue with the abovementioned developments, Kateb argues that they constitute ‘naturalist reductions’ of the human species that ‘unnecessarily tarnish human dignity by taking away commendable uniqueness from it’ (2011, p. 128). ‘Naturalism’, as understood here, is the view that everything, including the human, is explicable by reference to the laws of nature. Facts about humans’ and other beings’ properties have normative ramifications, according to naturalists, as these facts impose constraints on how we ought to treat these beings morally and legally.

As I argue in this article, there is hardly anything new about this ‘new’ dignitarianism. The dignitarian response to threats to human uniqueness goes back to the Enlightenment, when dignitarians were faced with the challenge posed by findings of naturalists which seemed to question their view of human beings as unique creatures, endowed with a dignity that no other being possesses. As I will show, many of the central arguments that are put forward in contemporary dignity and human rights scholarship are a mere reiteration (albeit unwitting) of positions held in the Enlightenment. This intellectual history of dignitarianism and naturalism sheds new light on the contemporary debate between human dignity and human rights scholars on the one hand and nonhuman rights scholars on the other. Dignitarianism and naturalism were only just budding in the Enlightenment, which is why, if we study them in this formative period, we can acquire an understanding of the central elements of these conceptions and the reasons people had for adopting them that would remain hidden to us in the thicket of today’s debate.

The purpose of this article, however, is not only to provide a glimpse behind the scenes, as it were, and to enrich the contemporary debate with a deepened understanding of dignitarian and naturalist arguments. Its purpose is also practical: it will reveal an inherent problem with naturalism and dignitarianism—which I will call the Zero-Sum Problem—and it will propose practical ways of overcoming this problem. As I will show, the core elements of dignitarianism are the exact opposite of naturalism’s central elements. Based on this finding, I will argue that dignitarianism and naturalism are best understood not as independent conceptions, but as ideal-types located on opposite sides of a normative spectrum. As negative images of each other, dignitarianism and naturalism are antithetical in that none can be said to be superior to the other. Whatever we gain by approaching one ideal-type, we lose by moving away from the other. Awareness of this Zero-Sum Problem is of great practical relevance as it explains why dignitarians and naturalists have failed to resolve their conflicts—and, indeed, why such resolution is impossible. As I will argue, accepting this fact is a first and necessary step to more moderate and more practically viable theories that attempt to find an equilibrium between the two ideal-types. Studying the historical forebears of contemporary dignitarian and naturalist accounts is therefore not only central for a deepened understanding of the raison d’être and the workings of these positions, but it is also crucial for finding practical answers to their inherent problems. We can find these answers only if we see the root of the problem. And we can get at the root only if we cut through the thicket first.

The article is divided into three sections. I first outline the current debate between modern-day naturalists and the ‘new’ dignitarians (‘The Rediscovery of Human Dignity’ section). I then demonstrate that the arguments made by proponents of these two camps have already been voiced two hundred years ago, in an exchange between the Enlightenment philosophers Jean-Baptiste Salaville and Jean-Claude de la Métherie (‘Back to the Future’ section). To explain why contemporary arguments are in many ways a reiteration of this Enlightenment debate, I propose to interpret them as representative of two opposing ideal-types on a normative spectrum and examine the architecture of these ideal-types (‘Naturalism and Dignitarianism as Ideal-Types’ section). Finally, I show that the spectrum deepens not only our understanding of dignitarianism and naturalism, but that it also exposes a philosophical problem: the Zero-Sum Problem. This problem explains why conflicts between naturalism and dignitarianism are irresolvable and it points to an equilibrium that individual approaches need to find in order to be practically viable (‘The Zero-Sum Problem’ section).

The Rediscovery of Human Dignity

The commonplace that human beings are endowed with unique dignity and exclusive human rights has become increasingly challenged in recent years. Developments in fields as diverse as biotechnology, animal cognition, and computer science are mounting the pressure on the special moral and legal status of human beings. Lawyers and philosophers have drawn on these new findings to argue for an extension of human rights to nonhuman beings. As I will show in the second half of this section, these proposals have recently encountered significant resistance by scholars who invoke human dignity to argue that human rights belong to humans only.

In biotechnology and the biomedical sciences, significant advances are opening up possibilities for modifying core components of human nature, such as our genetic makeup. As Allen Buchanan points out in a book debating the ethical issues raised by these developments,

[b]iotechnologies already on the horizon will enable us to be smarter, have better memories, be stronger, quicker, have more stamina, live longer, be more resistant to diseases, and enjoy richer emotional lives. (2011, p. 1)

It is conceivable, Buchanan argues, that such human enhancements could lead to the creation of a new and enhanced type of ‘posthuman’ (2011, pp. 212–213). The ‘posthuman’ race, he points out, would hold some of the rights that were formerly considered to be exclusively human because they would likely possess some of the capacities and interests that ground humans’ rights today (2011, p. 214). At the same time, it is possible that due to the special capacities and interests that only ‘posthumans’ possess, they may be owed rights which unenhanced humans do not possess. Some have imagined enhanced beings with a significantly increased sense of empathy, for example (see e.g. Savulescu and Persson 2012, p. 401). If such beings were to see the light of day, their interests in being empathetic might have to be protected by (at least prima facie) rights. As Daniel Wikler (2009, p. 346) observes, it is furthermore imaginable that respecting unenhanced humans’ rights would impose too burdensome duties on the enhanced humans. As a consequence, they may be justified in curtailing the rights of the unenhanced, in a similar way as human beings may feel overburdened by respecting the rights of, say, insects. Francis Fukuyama (2002, p. 10) puts the conundrum raised by these developments succinctly when asking: ‘What will happen … once we are able to, in effect, breed some people with saddles on their backs, and others with boots and spurs?’

Proponents of animal rights have pursued similar lines of reasoning which challenge the exclusivity of human rights. Drawing on findings in animal cognition, and zoology more generally, they point to the fact that numerous animals share the capacities and interests we take to ground a range of human rights, such as for example the right to life, the right to bodily integrity, or to personal freedom. The Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP), which has been filing writs of habeas corpus in New York State courts in order to have chimpanzees recognised as legal persons with fundamental rights, is an example. To substantiate their petitions, the NhRP has filed a series of affidavits from prominent primatologists, establishing ‘that chimpanzees possess such complex cognitive abilities as autonomy, self-determination, self-consciousness, awareness of the past, anticipation of the future and the ability to make choices; display complex emotions such as empathy; and construct diverse cultures’. The possession of these capacities and the interests to which they give rise, the NhRP argues, are ‘sufficient to establish common law personhood and the consequential fundamental right to bodily liberty’ in chimpanzees (Petition to the State of New York Supreme Court, County of Suffolk, The Nonhuman Rights Project, Inc. v Samuel L. Stanley and Stony Brook University, 2 December 2013, p. 2).

Advances in computer science, and artificial intelligence more specifically, are raising yet another challenge to the human exclusivity of human rights. It is conceivable that in the not too distant future, robots and AIs will be created with features similar to those which are often taken to ground rights in human beings. Would we therefore owe them human rights? As Alasdair Cochrane argues,

it is at least possible that advances in artificial intelligence may one day lead to the creation of robots or other machines who have the capacities for consciousness or even moral autonomy. And if they possess the morally relevant characteristics, it is hard to see why these robots ought to be denied human rights. (2012, p. 319)

Cochrane rightly points out that if human rights extend to beings as diverse as posthumans, AIs, robots, and nonhuman animals, then we have good reasons for finding a more suitable label than ‘human rights’. He proposes to adopt the term ‘sentient rights’ as a more accurate reflection of the categories of beings these rights protect ( Cochrane 2012, p. 320, 2013).

In recent years, the enthusiasm with which authors such as Cochrane have argued for an extension of human rights beyond the human species has been met with a wave of scholarship defending the exclusivity and equality of humans’ rights by invoking human dignity. This invocation of dignity to thwart (perceived) threats to the human species has first been noticed in the debates surrounding the development of new biotechnologies in the early 2000s. As Timothy Caulfield and Roger Brownsword (2006, p. 74) observed in 2006, ‘the concept of human dignity is increasingly used as a non-negotiable, one-line, reason for prohibiting some proposed application of biotechnology’. Referred to as ‘new dignitarianism’ (Caulfield and Brownsword 2006, p. 72), this movement has since widened its target, turning into what Will Kymlicka (2017, p. 7) has called a ‘new dignitarian politics’. This politics is characterised by its efforts to salvage the special status of humanity and its privileges from any kind of dilutions and debasements believed to result from tampering with human nature, from recognising similarities between human beings and nonhuman beings, and from granting moral and legal recognition to nonhuman entities based on these similarities.

One telling notion that some dignitarians have reclaimed to defend the idea that human beings are special and that they should be the exclusive holders of dignity and human rights is that of ‘aristocracy’. Most prominently, Jeremy Waldron (Waldron 2012) has argued that human dignity, as it is used in legal practice, is best understood as a rank (or status) concept comparable to that previously held by aristocrats.Footnote 1 In contrast to noble rank and privileges, however, human dignity and human rights are not limited to a certain subgroup of people but rather extend equally to all members of the human species. Equality of rights and dignity thus bear an intimate connection, as Waldron has pointed out more recently (2017, pp. 3–4): ‘Human dignity presupposes an equality of worth or standing among humans but it adds to that an additional stronger thesis … about distinctive human worth’.

A crucial consequence of the fact that all human beings are equal holders of dignity and rights is that we ought not distinguish between different human beings in the way we distinguish between humans and nonhumans. As Waldron emphasises, ‘[t]he principle of basic equality is opposed to any claim that there are moral distinctions and differentiations to be made among humans like unto or analogous in scale and content to the moral distinctions commonly made between humans and other animals’ (2017, p. 30). According to dignitarians such as Waldron, human rights are the privileges that come with the status of human dignity. It would therefore be a mistake to grant rights only to some human beings and not to others based on the argument, invoked by naturalists, that they lack the features that ground these rights. For dignitarians, Waldron notes, the whole point of upholding human dignity and equality is ‘to say that no such sort of thing applies within the human realm’ (2017, p. 30). Kateb, in Human Dignity (2011, p. 9), defends a similar position. He argues that the status of equal dignity that humans possess

means that the question of which individuals in the human species are ‘best of breed’, let alone ‘best in show’, is out of order. Of course people vary in their talents and innate abilities, and in the manner of their acculturation, but that undefinable fact is irrelevant to human status.

In a critique of the NhRP’s attempts at gaining legal personhood and rights for chimpanzees, Richard Cupp (2016, p. 37) aptly articulates the central concern that underlies this recent wave of dignitarianism. ‘The sky would not immediately fall if courts started treating chimpanzees as persons’, Cupp notes. ‘But over time, both the courts and society might be tempted to not only view the most intelligent animals more like we now view humans, but also to view the least intelligent humans more like we now view animals’. Once we ground rights in the possession of certain properties shared also by nonhuman beings, what prevents us from using the same criteria to create separate classes of human beings, some of whom will come out on the short end, with less rights, while others will end up with a higher status and more rights? As far as naturalists are concerned, only sane adult human beings may deserve the most complete set of human rights, for only they possess all the necessary capacities that ground these rights.Footnote 2 Infants and mentally disabled human beings lack some of these capacities, which is why they should not be granted the corresponding rights. In common with some nonhuman beings, however, they will possess other capacities, such as sentience, which justifies their possession of some other rights, such as the right to bodily integrity.

Dignitarians are worried that once we are open to this idea of differential consideration, we are on a slippery slope. Human beings would be in danger of losing not only their special status, but also their equality. As Laurence Tribe (2001, p. 7) cautions, if we accept such differentialism, we will also have to ‘decide about people who are three-quarters of the way to such a condition. I needn’t spell it all out, but the possibilities are genocidal and horrific and reminiscent of slavery and of the holocaust’. For these reasons, the ‘new’ dignitarians contend that we must maintain a clear distinction between how we treat nonhumans and how we treat humans. If we fail to do so, ‘we may end up by treating human beings as badly as we treat animals, rather than treating animals as well as we treat (or aspire to treat) human beings’, as Richard Posner has pointed out (2000, p. 535).

Back to the Future

Two hundred years before Posner, in 1803, the Parisian philosopher Jean-Baptiste Salaville put pen to paper to compose an essay entitled De l’homme et des animaux with a message that could hardly be any more similar to that of the ‘new’ dignitarians. ‘In trying to lift animals to the status of humans’, Salaville criticised the then emerging naturalist movement, ‘humans are brought down to the status of animals. This doctrine, ostensibly human, is in fact full of injustice and inhumanity’Footnote 3 (Salaville 1805, p. 53). In claiming that humans and animals differ only in degree and not kind, naturalism, according to Salaville, poses a serious threat to the inherent dignity of humanity. Salaville, who was a steadfast republican and egalitarian, argued that human nature is special because it ‘comprises an excellence and a dignity of which other natures are devoid’ (1805, p. 52). Hence, he warned, to fail to distinguish strictly between humans and animals, ‘is to confound what must be carefully differentiated’ (1805, p. 35). Fearing that even mere comparisons between human beings and ‘vulgar’ animals would result in a degradation of the former, Salaville made it his declared aim to salvage the special dignity of human beings by rejecting, once and for all, the claims made by the naturalists (Salaville 30 Thermidor Year XIII, p. 343).

Salaville structured his essay around the question whether barbaric treatments of animals ought to be of concern to public morality. For this to be the case, Salaville argued, they would have to offend the ‘sentiment of humanity’, that is, humanity’s willingness to help others in need. His key question therefore became the following: Does the way we treat animals, or the sight of such treatments, distort or destroy the precious sentiment of humanity? Only if it does do we have reason to adopt laws against the barbaric treatment of animals. Unfortunately for animals, Salaville argued that their ‘cruel’ treatment cannot adversely affect the sentiment of humanity because they lack intelligence, which he considered to be necessary for having the capacity to feel pain. Only human beings, he believed, possess the intelligence that is required to be affected by degrading treatments and that therefore serves as the basis for humans’ moral dignity, which commands respect by the feeling called ‘humanity’ (1805, p. 35). Animals completely lack any such dignity, which is why we should not extend this feeling to them. Not only would such an extension be pointless, Salaville cautioned, it would also be positively harmful: ‘By giving everything the same colour, you disenchant the nature you think to embellish’ (1805, p. 56). To protect the invaluable sentiment of humanity, Salaville proposed that

[i]t is, therefore, not by drawing attention to animals that we can hope to increase and consolidate interest in man; if there is a means of assuring the inviolability of the latter, it is … to render it exclusive; it is to admit that man and animals differ by their respective natures and that this difference authorises and makes legitimate with respect to them what it prohibits with respect to us. (1805, p. 51)

While Salaville’s invocation of the exclusively human dignity was directed against the general naturalist current of the time, he had one particular person in mind when writing his essay. ‘If we are to believe a physicist of our day’, Salaville pointed out tauntingly in his foreword, ‘“man, belonging to the family of apes, was originally covered with hair like them, inhabited the warm countries,” etc.’ (1805, p. viii). The ‘physicist of our day’ Salaville was referring to was Jean-Claude de la Métherie, a Parisian contemporary of Salaville’s with monarchical leanings.

If contemporary dignitarianism is a carbon copy of Salaville’s theory, then so is contemporary naturalism of Jean-Claude de la Métherie’s. Central to de la Métherie’s theory, which he presented in his Principes de la philosophie naturelle, was an emphasis on the sensations of beings. This view is still common today, albeit in modified form, with most talking of ‘sentience’, ‘interests’, ‘needs’, or ‘capabilities’. With sensations being the only epistemic currency, de la Métherie’s approach automatically put the spotlight on beings who are capable of having such sensations. Êtres sensibles (sensitive beings), as de la Métherie called them, are able to experience both harmful and pleasant sensations, and, as a matter of universal law, always strive for the latter (1787, pp. 41, 140–141).Footnote 4 Immediate normative consequences follow from this: in addition to having a duty to improve their own happiness and not to deprive others of theirs, de la Métherie argued, sensitive beings also have positive moral obligations to improve the lot of all other sensitive beings. These positive obligations apply regardless of species, which is why de la Métherie considered preferential treatments for members of one’s own species—a view referred to today as ‘speciesism’—to be irrational. All that matters, in de la Métherie’s view, are the sensations that individual beings have.

Perhaps even more striking is his claim that this principle not only applies to earthlings, but also to inhabitants of other worlds and, indeed, to any other sensitive being conceivable:

[T]he inhabitants of the different globes, if they exist, as we can conclude by analogy, and all sensitive beings that may exist, and we shall see that their number is immense, must … seek their mutual happiness. We, citizens of the earth, are also obliged to work for the happiness of all these beings, if it is in our power. They, too, are required to contribute to ours. (1787, pp. 196–197, emphasis added)

Corresponding to the duties humans have to respect and promote the well-being of other sensitive beings, de la Métherie argued, are the fundamental rights that these beings possess to their well-being, in virtue of the fact that they are sensitive beings. In a pioneering move that anticipated animal rights theories as formulated by modern thinkers such as Tom Regan or Gary Francione, de la Métherie argued that because animals are sensitive beings like humans, they should possess similar rights to humans. More specifically, de la Métherie proposed that animals should have a triad of fundamental rights: the right to life, the right to health, and the right to enjoyments (plaisirs) (1787, pp. 200–201). While he did not specify what exactly ‘enjoyments’ entails, he did point out that they are related to the senses, the spirit, and the heart. This suggests that he could have had pleasurable experiences, such as play, companionship, and even sexual gratification in mind, since he explicitly argued that animals have a right to reproduce.

With respect to the latter right in particular, but also the triad of fundamental rights more generally, practical problems arise. To what extent should animals be allowed to multiply? What enjoyments should they have? What level of healthcare can they claim? Are there no circumstances under which an animal may be killed? To all these questions, de la Métherie had an answer which is surprisingly similar to the one given by many contemporary rights theorists. Regarding the fundamental right to enjoyments, for instance, de la Métherie pointed out that we need to ‘reconcile the needs of the individual with what the common good demands’ (1787, pp. 223–224). The interests of the individual, to use modern rights terminology, have to be ‘balanced’ against the rights of other individuals and against public interests.

It is further worth noting that de la Métherie did not argue that humans and animals should possess the same fundamental rights. According to de la Métherie, there are rights and obligations that can only apply to human beings. Human beings have interests that go beyond those which ground the trinity of rights in other animals: for example, humans have a need to clothe themselves and to have adequate accommodation. These special interests give rise to rights in human beings that are not owed to other animals.

But de la Métherie also did not claim that all human beings should be granted the same rights. This is where we begin to see the pertinence of Salaville’s critique. In 1802, de la Métherie published another treatise called De l’homme considéré moralement: de ces mœurs, et de celles des animaux in which he makes explicit some of the tendencies that have already informed his 1787 work (see Serna 2016, pp. 218–220). The fundamental tenet of de la Métherie’s later treatise is his claim that there is hierarchy in nature. The most perfect beings are at the top of this hierarchy, the least perfect ones at its bottom. Across different species, de la Métherie argued, humanity is the most perfect species because it possesses the most excellent qualities. He believed that differences in such qualities also exist within species. Especially among human beings, he argued, there are significant differences. The most important such difference is that between human beings who, like animals, live in the state of nature, and those who live in a civilised state. For de la Métherie, the former are lower in the hierarchy than the latter. And among the peoples who have left the state of nature, he considered those to be further down who work manually and are poor (1802, pp. 7, 38, 256–261). It is exactly to such degradations of human beings and to the rejection of the principle of equality that Salaville wanted to put a stop. Only by establishing a firm line between humans and animals, he believed, can the special status and dignity of humanity be preserved.

I hope it will become apparent over the course of the next section why an awareness of the debate between Salaville and de la Métherie is useful for us today. Before we move on, however, I need to emphasise the limitations of de la Métherie’s and Salaville’s texts. First, neither their exchange, nor, a fortiori, any of the texts on their own, gave rise to modern naturalist or dignitarian positions. Salaville’s and de la Métherie’s debate remained relatively unknown, even to contemporaries.Footnote 5 Second, while defending similar views to many of today’s theorists, Salaville and de la Métherie were writing at a time when many of our modern concepts had not yet been developed and were only beginning to take shape. For this reason, we should not be surprised that there are still important differences between Salaville’s and de la Métherie’s language and arguments and those of contemporary scholars. Third, de la Métherie and Salaville were certainly not the first ones to think along the lines presented in their essays. In more rudimentary forms, similar arguments to theirs have surfaced at least since antiquity (see e.g. Bodson 1983; Englard 2000, p. 1905). Fourth, history is scattered with examples of naturalists (e.g. Jeremy Bentham, Charles Darwin) and dignitarians (e.g. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Immanuel Kant) of some kind. The historical point of this section could therefore likely also have been made by drawing on other thinkers than de la Métherie and Salaville. I instead chose to focus on their accounts precisely because they are relatively unknown. This obscurity grants readers a more immediate access to the ideas themselves, without the usual prepossessions and distractions that come with discussing more famous authors. For these reasons, the point of presenting debate between our two philosophers was not genealogical: I do not argue that Salaville’s or de la Métherie’s theories gave rise to contemporary theories. The point, rather, was to reveal the architecture of the two ideal-types of which de la Métherie’s and Salaville’s views are illustrative examples, and which have become influential since the Enlightenment. In the remainder of this article, I analyse these two ideal-types and demonstrate their practical relevance.

Naturalism and Dignitarianism as Ideal-Types

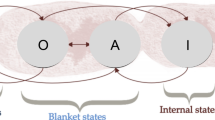

In this section, I propose to interpret de la Métherie’s and Salaville’s accounts as representative of two ideal-types—naturalism and dignitarianism—which became prominent in the Enlightenment, and which are still dominant today. The two philosophers’ accounts are particularly useful for analysing the architecture of these two ideal-types because they reveal the central arguments dignitarians and naturalists used when their conceptions were still in the early stages of development. Their accounts therefore permit a glimpse of the core features of dignitarianism and naturalism before these conceptions started to grow rampant and made it difficult to discern which of their features are important and which ones are not. As I will show, this glimpse of the core elements of dignitarianism and naturalism reveals that they are not independent positions but that they are on opposite sides of a normative spectrum. They can therefore only be fully grasped if we understand one in contrast to the other. I will focus on three of the central structural elements of these antithetical positions, which illustrate what I call the ‘spectrum of naturalism and dignitarianism’ (see Fig. 1). Each of these elements is to be understood as the negative image of the corresponding element of the other ideal-type. The first element describes what the main contention of the ideal-type is (differential consideration in naturalism, equal consideration in dignitarianism). The second element addresses how the ideal-type forms this contention (externalism in naturalism, internalism in dignitarianism). The third element, finally, concerns the reasons why the ideal-type has been appealed to (‘grounding’ in naturalism, ‘founding’ in dignitarianism). As illustrated in Fig. 1, individual theories (x, y) approximate these elements to greater or lesser extents, thereby making them more or less ‘naturalistic’ or ‘dignitarian’. Because the two positions are ideal-types, none of the accounts that we find in practice may be perfect instantiations of either naturalism or dignitarianism. It is furthermore important to note that while the naturalist and the dignitarian ideal-types that I will be presenting are on opposite sides of the spectrum, they are not necessarily the most radical proponents of these opposing sides. On the naturalist side, more radical conceptions could, for example, include views that extend rights not only to animals, but to nature more generally (see e.g. Leopold 1966). On the dignitarian side, one could imagine more extreme conceptions that confer dignity and basic rights only to a certain subgroup of human beings (much like in the Ancien Régime). The naturalist and dignitarian conceptions I discuss are therefore not the only possible positions on their respective sides. However, I take them to be particularly salient representatives, which is why I focus on them rather than on their more radical siblings.

Differential Consideration Versus Equal Consideration (1)

The first pair of opposing elements answers the question what the main contentions of our two ideal-types are. In the case of dignitarianism, it is equal consideration, and in the case of naturalism, it is differential consideration. Let us start with differential consideration. Naturalists reject the idea that membership in a particular species itself is morally relevant. What they consider relevant, instead, are empirically discoverable properties of individual beings, such as consciousness, sentience, rationality, and so on. In virtue of this focus on individuals’ properties, comparisons between humans and nonhumans who possess similar properties are not only appropriate, but consistency even requires according them similar moral treatment (see McMahan 2005, p. 354; see also Singer 1990, p. 6).Footnote 6 Recall, for example, de la Métherie’s argument that all sensitive beings should possess the right to life, to health, and to enjoyments based on the fact that they possess certain capacities (above all, the capacity to have sensations). To the extent that human beings differ in their capacities from other animals, de la Métherie argued, they should possess special rights to protect the interests that result from these capacities. And to the extent that individual human beings possess features that other humans do not, they should also be granted other rights. In contemporary moral philosophy, this view has become known as ‘moral individualism’. James Rachels, who popularised it, explains that its ‘basic idea is that how an individual may be treated is determined, not by considering his group memberships, but by considering his own particular characteristics’ (1999, p. 173). This approach is captured well by Cochrane, who argues that an account of fundamental rights needs to reflect real differences: ‘because different sentient beings have different basic interests … they have differentiated sentient rights’ (2013, p. 667). As naturalists point out, this also explains why attempts at grounding the principle of equality in individuals’ properties fail. The central problem with such attempts, as McMahan (2008, p. 95) puts it, ‘is that we are held to be normatively equal and our moral status is held to supervene upon facts about our nature, yet there are really no relevant respects in which we are by nature equal’.

On the opposite side of naturalism’s differential consideration is the equal consideration dominant in dignitarianism. Equal consideration requires that all human beings be treated as equals. Under this view, as Salaville pointed out, it is neither here nor there that some humans surpass others in intelligence or strength, because we simply assume that all human beings are equals and that they have the same claim to human dignity. The flip side of this equal consideration of human beings is the exclusion of all those who are not part of the community of equals, that is, all nonhumans. As Salaville (1805, pp. 37, 51) claimed, they lack intelligence, and therefore dignity. For this reason, he argued, it is our moral duty to insist on an insurmountable abyss that separates humans from nonhumans. Contemporary dignitarians argue along roughly similar lines. Kateb, for instance, contends that ‘we human beings belong to a species that is what no other species is; it is the highest species on earth’ (2011, p. 17). In this unique nature, he holds, lies our dignity and equality.

Equal consideration should not be confused with the claim that all humans ought to be treated the same. Under dignitarianism, human beings need to be treated as equals, but not necessarily equally. Ronald Dworkin (2013, p. 273) elucidates this distinction by arguing that treating someone equally is about giving them an equal share of some resource or burden, whereas treating someone as an equal is to treat them ‘with the same respect and concern as anyone else’: ‘If I have two children, and one is dying from a disease that is making the other uncomfortable, I do not show equal concern if I flip a coin to decide which should have the remaining dose of a drug’. Hence, dignitarians may point out, their position is no stranger to differential concern. Quite the opposite: equal consideration requires us to take into account differences between human beings and to treat them differently based on these differences.

But if equal consideration can accommodate differences between human beings, where does this leave naturalism’s differential consideration? In contrast to what the aforesaid might suggest, there is still a real and important difference between equal consideration and differential consideration. The difference is that equal consideration is premised on the assumption that those to whom we owe equal respect and concern have equal worth. As John Rawls puts it, equality ‘applies to the respect which is owed to persons’ (Rawls 1971, p. 511, emphasis added). Personhood is taken to be the moral baseline that determines which treatments we owe to people in order to respect them as equals. Equal consideration thus has an underlying commitment to equal worth which governs its sensitivity to individual differences. Naturalism has no such commitment to equal worth. If a particular human being turns out to have a stronger interest in life, perhaps due to advanced mental capacities to make plans for the future, then differential consideration assigns greater moral value to that human’s life than to someone else who has a weaker interest. In case of a conflict, the former’s right to life would outweigh that of the latter.

Externalism Versus Internalism (2)

The second pair of opposing elements addresses the question how the two ideal-types arrive at the abovementioned contentions. In the case of dignitarianism, the approach is that of internalism, and in the case of naturalism, it is that of externalism. What do I mean by ‘externalism’? In their recent volume on human rights and human nature, Marion Albers, Thomas Hoffmann, and Jörn Reinhardt define externalism as the attempt

to justify elementary moral and legal principles from ‘outside’ our normative or evaluative vocabularies. The … ambition is to trace a normative concept back to certain non-normative descriptions of human beings as formulated in the vocabularies of the natural sciences. (2014, p. 2)

Following this definition, we can say that naturalism seeks to ground normative principles in empirical features of the beings to whom these principles apply. Take de la Métherie’s argument in favour of a sensitive being’s right to life, health, and enjoyments. For de la Métherie, membership in a particular species or group is itself irrelevant for determining whether the being counts morally. What matters instead is that it can be shown empirically that the being is capable of having sensations. This view has lost none of its appeal to contemporary naturalists. Especially those defending so-called interest-based approaches to rights, which ground rights in a being’s interests, are prone to externalism. According to Cochrane and Steve Cooke, for example,

it is reasonable to propose that animals possess the right not to be made to suffer. Given that animals are capable of experiencing suffering, and given that suffering ordinarily makes life go worse for sentient creatures, it makes sense to say that all sentient animals have a compelling interest in not being made to suffer. (2016, p. 110)

On the other end of the spectrum, we find internalism as the second element of dignitarianism. Internalism can be defined as the attempt ‘to justify the universal validity of human rights by referring to a concept of human nature that is normative from the beginning’ (Albers, Hoffmann, and Reinhardt 2014, p. 2). Under the internalist approach, normative principles such as the principles of dignity and equality are not grounded in empirical facts about the beings to whom they apply, as those facts would qualify as ‘external’ to the principle. Rather, these principles are justified by reference to other normative (‘internal’) principles or assumptions such as, for example, the assumption that all human beings are owed respect in virtue of a mutual agreement to recognise each other as equals. To be sure, not all dignitarians adhere to internalism. For example, those who argue that dignity is God-given reject it (see Schroeder and Bani-Sadr 2017, p. 46). However, many still endorse it (see Rossello 2016). Michael Rosen, for example, argues that statuses such as human dignity are ‘agreed social conventions’ (Rosen 2012, p. 145). For Rosen, concepts such as human dignity or rights do not in themselves bear any content, in the same way as ‘there is no fact beyond social acceptance that underlies the chess piece with a horse’s head entitled to move in an “L”-shape.’ That human dignity and rights are presupposed in this way is also emphasised by Paolo Carozza (2014, p. 621), who reminds us that the drafters of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights could not agree on a specific justification for human rights, and simply settled for pragmatic consensus. ‘The human rights enterprise’, he infers, ‘is built on practical agreement, tout court’.

Grounding Versus Founding Humanity (3)

The third and last pair of elements addresses the question why naturalism and dignitarianism have become such prominent positions since the Enlightenment. The appeal of naturalism’s externalism is its ability to ground humanity in facts about nature, while the appeal of dignitarianism’s internalism lies in its converse capacity to found humanity regardless of empirical facts. Let us start with the former, and analyse what I mean by ‘grounding’ of humanity. In philosophical discourse, the term ‘to ground’ is typically used in a figurative sense to describe the act of providing a foundation (empirical, metaphysical, or otherwise) for a normative principle. In a more literal sense, the verb ‘to ground’ describes the process of connecting electrical devices to the earth. Naturalism captures both the figurative and literal sense of ‘grounding’: it provides humanity, and the principles applying to it—dignity, basic equality, fundamental rights, and so on—with a foundation in its earthly, empirical nature.

That this approach provides normative principles with a solid foundation can be considered naturalism’s main strength and appeal. For instance, the fact that humans and many animals are sentient is unlikely to change, which is why their corresponding right not to be made to suffer has a firm foothold. This is not to say, however, that externalism is committed to the view that these normative principles are fully reducible to empirical facts. Externalism is only committed to the view that normative principles supervene on non-normative facts, that is, that the way beings are informs (but not necessarily fully determines) how we ought to treat them. The underlying empirical facts make sense of our normative principles, thereby rendering these principles less arbitrary and more plausible (see on this Waldron 2017, p. 86).

Paradoxically, this central role of empirical facts is also naturalism’s central weakness. Once we allow for such facts to influence the way we ought to treat one another, we open the door for moral differentiations between human beings that are widely considered to be inacceptable. For example, as pointed out above, we would have to let go of the idea that all human beings have equal moral worth. Those with stronger interests in their lives would have to be granted stronger protections than those with weaker interests. Differential consideration therefore seems to open the door to a division of humanity into subgroups with unequal rights. Justin Smith (2015) has shown convincingly that the trend toward such divisions started in the Enlightenment, when naturalists stopped seeing humanity as inhabiting a special ontological realm that is wholly separate from that of other animals. While they had previously compiled taxonomies of other forms of life, humans themselves now started to become the object of scientific study, to be assigned their proper place in the taxonomies. ‘[W]hen human beings were fully inserted into nature’, Smith points out, ‘the unity of the human species was lost, and different groups were now held, themselves, to have different “natures”’ (2015, p. 18).

To avert this problem, dignitarians found humanity. The verb ‘to found’ here refers to the act of establishing or creating something new. In contrast to grounding, the process of founding does not base principles on empirical facts. Following the internalist approach, it instead creates its own foundations by drawing on existing (‘internal’) assumptions and normative principles. This mode of thinking has a venerable tradition and, against what some might suspect, does not necessarily boil down to crude decisionism. Which principle is adopted is generally not a matter of arbitrary choice, but the result of a refined process, referred to by Dworkin as the process of interpretation (2011, pp. 67, 102). According to Dworkin, the justification of a moral principle such as the principle of dignity as well as challenges to that principle cannot proceed except by invoking and knitting together other moral principles and practices. The best interpretation of the principle is one that ‘achieve[s] an overall integrity’ (2011, p. 101).Footnote 7

Founding humanity in this internalist way is necessary to overcome the challenge that natural differences between human beings pose to basic equality and dignity. Salaville (1805, p. 16) already seemed fully aware of this when asking the naturalists provocatively: ‘Is there not also a more and less among human beings? Are not some superior to others in intelligence, corporeal strength, natural faculties and acquired faculties?’ Salaville’s point was that, while there may very well be such descriptive differences between human beings, they should not matter normatively when it comes to granting dignity, equality, and rights. To ensure the integrity of the status and rights of all human beings, Salaville proposed, we should simply ‘admit’ that there is a fundamental chasm between humans and animals (see 1805, p. 51). We should, in other words, start from the assumption that humans ought to be treated differently than animals; that dignity and rights should be exclusive to human beings.

This is the strong suit of dignitarianism’s founding of humanity. Because the normative principles applying to it are not reducible to empirical facts, no fact about human beings—or about other beings, for that matter—can challenge them (Phillips 2015, p. 44). They become ‘impregnated’ against all criticism that is not internal, that is, that does not directly challenge the normative foundations on which they stand (Pollman 2014, p. 123). Hence, as far as internalism is concerned, the fact that not all human beings possess the same capacities is irrelevant for their dignity and equal rights (see Kateb 2011, p. 9). This ‘impregnation’ explains dignitarianism’s appeal in times when naturalists contest the uniqueness of humanity and thereby threaten its status and privileges. By remaining within an internalist framework, dignitarians can parry these threats. To use Brownsword’s formulation (2014, p. 347), they can ‘appeal to human dignity in order to stop science’.

However, there is a price that dignitarians have to pay for this immunity to external criticism. By erecting normative principles on other normative assumptions, dignitarianism becomes circular and thereby deprives itself of an external means of conferring plausibility on its normative principles. Dworkin may be right that identifying the best interpretation of a principle is not simply an arbitrary decision, but a sophisticated process of weaving together existing practices and principles. However, that does not mean that internalism is sufficient to render an adopted principle plausible. Waldron illustrates this point with the example of a society that interprets the principle of basic equality in a way that considers teapots and teenagers one another’s equals (see Waldron 2017, p. 59). Suppose this interpretation of the equality principle emerges the winner from the interpretive process in that society (one with a penchant for tea or low esteem for adolescents, one imagines). Would we expect anyone in that society to follow this principle despite the evident factual differences between teapots and teenagers? As Waldron observes, it would be absurd not to take into account the extent to which this interpretation of the equality principle matches the empirical world. The fact that teapots are made for pouring tea and teenagers, at best, for drinking it, means that this interpretation is much harder to make sense of than an alternative interpretation according to which teapots are excluded from the community of equals. Dworkin (2011, p. 100) admits that his internalist approach has its hands tied in cases like this where there is a manifest mismatch between the best interpretation and the factual reality, arguing that his interpretive theory cannot ‘test the accuracy of my moral convictions except by deploring further moral convictions’. He therefore rightly concedes that even a sophisticated internalist approach is ‘always guilty of a kind of circularity’.

For these reasons, we can agree with Waldron that in order to make sense, normative principles need to at least indirectly map onto facts about the beings to whom they apply. Hence, although such facts cannot render normative principles invalid under internalism, they can still deprive them of their plausibility if they do not overlap sufficiently with reality. This, then, is dignitarianism’s greatest weakness. With its reliance on entirely normative principles, it is in danger of having the rug pulled out from under its feet.

The Zero-Sum Problem

In the previous section, I have built on Salaville’s and de la Métherie’s accounts to uncover the core elements of dignitarianism and naturalism and have proposed to interpret them as two opposing ideal-types on a normative spectrum. This spectrum allows us to locate individual theories between the two ideal-types of, on the one hand, full-blown equal consideration, internalism, and founding, and full-blown differential consideration, externalism, and grounding on the other (see Fig. 1). In this section, I will show that conceiving of naturalist and dignitarian theories on this spectrum deepens our understanding of dignitarian and naturalist arguments and that it lays bare a thus far neglected problem—the Zero-Sum Problem—which has important practical consequences: it explains not only why dignitarians and naturalists have failed to resolve their conflicts since the Enlightenment, but it also points to practical ways of overcoming this problem.

First, conceiving of naturalist and dignitarian theories on a normative spectrum deepens our understanding of these positions and their driving forces. For example, with the aid of this account, we can identify what the ‘new’ dignitarian theories are responses to: they are responses to threats stemming from the abovementioned developments in bioethics, animal cognition, and computer science and the naturalists’ rejection of humans’ special dignity and exclusive rights. Adopting the spectrum also allows us to better understand why the ‘new’ dignitarians counter the naturalists’ claims: dignitarians (re)claim dignity to salvage the unique and special status of humanity in the face of mounting claims about empirical similarities between human and nonhuman beings and about empirical differences within the human species. Finally, the spectrum allows us to understand how the ‘new’ dignitarians achieve this feat: they resort to the internalist approach which allows them to disregard these empirical claims by founding dignity, equality, and the rights of all and only human beings.

Once we are in a position to understand the ‘what’, ‘why’, and ‘how’ of dignitarianism and naturalism, we are able to predict the behaviour of individual dignitarian and naturalist theories, can anticipate complications, and propose remedies for overcoming them. Key to this is the insight that the two opposing sides exert a pull that is difficult for individual theories to resist. The pull of the dignitarian ideal-type drives human dignity and human rights accounts towards adopting something approximating equal consideration, internalism, and founding. The pull of the naturalist ideal-type, on the other hand, explains why nonhuman rights accounts tend towards differential consideration, externalism, and grounding. It is for this reason that human rights theories will find it difficult to abandon the dignitarian ideal-type and to approach naturalism (unless they want to jettison dignitarian elements). Consider the following example. A human rights account that wants to exclude all nonhumans from right-holdership but that endorses an interest-based approach to rights, and thereby approaches the naturalist ideal-type, will find it very hard to escape the gravitational field of naturalism that will pull it toward recognising nonhumans with relevant interests as right-holders. This has happened to John Tasioulas’s human rights theory, for example. Tasioulas, who started off with a pure human rights account has recently acknowledged in a footnote that his theory ‘allow[s] for the possibility that non-human animals may have rights’ (Tasioulas 2015, p. 54). Had he wanted to avoid this result, Tasioulas would have needed to refrain from adopting an externalist approach that grounds rights in interests, and should have instead opted for internalism. Of course, human rights approaches are not the only ones that feel such pulls. Nonhuman rights theories are equally subject to the forces in the spectrum. They, too, face complications if they distance themselves from naturalism and try to incorporate dignitarian elements. For example, as discussed above, the concept of dignity is inherently linked with the idea of a high and equal status. It is, as we saw, a central element of dignitarianism’s equal consideration. For this reason, animal rights approaches will find it more difficult to adopt the concept of dignity than human rights approaches. As Kymlicka (2017, pp. 8–9) points out, while many ‘concepts which we standardly use to discuss and defend human rights—interests, needs, well-being, capabilities, flourishing, vulnerability, subjectivity, care, justice—lead naturally to the recognition of animal rights, since animals are continuous with humans in all of these respects’, this does not hold true for the concept of dignity. As he rightly emphasises, ‘dignity is not the natural language of [animal rights] theory’.

Having thus acquired a better understanding of dignitarianism and naturalism, we are now able to see a problem that has so far gone unnoticed. As pointed out above, naturalism and dignitarianism are best interpreted as opposing ideal-types on a normative spectrum. Each of these ideal-types has a particular weakness, and this weakness has been shown to be the strong suit of the opposing ideal-type. It is therefore impossible for dignitarians to gain dignitarian advantages without at the same time incurring losses on the naturalist side, and vice versa. The more a theory tends to the dignitarian extreme, the more it has to disregard facts about the beings to whom its principles apply, and the less of a foothold it has in reality. Conversely, the more a theory turns towards naturalism, the less it is able to accord the same protection to all members of the same species. One cannot escape the forces that are at work in the spectrum; naturalists and dignitarians are playing a zero-sum game.

This explains why neither the dignitarian nor the naturalist camp has come any closer to winning the debate since its emergence in the Enlightenment. As demonstrated by the striking similarity between Salaville’s and de la Métherie’s and contemporary theories, little if any progress has been made on these issues. The Zero-Sum Problem explains why this is the case: because dignitarianism and naturalism are opposing ideal-types, attempting to determine a winner in this debate is like trying to establish whether black or white is the better colour. What speaks for one speaks against the other.

As I would now like to show, this insight can be put to practical use. While the antithesis of naturalism and dignitarianism makes it impossible to say that any one of these views is better than the other, it allows us to see more clearly what concessions an individual theory has to make in order to become more plausible for advocates of the opposing ideal-type. In making such steps toward that other ideal-type, a theory can become more practically viable.

To illustrate this point, consider the following two examples. The NhRP, as will be recalled, is a contemporary naturalist organisation that attempts to convince courts to recognise legal personhood and rights for chimpanzees based on their cognitive capacities. As one of its dignitarian critics, Cupp, has pointed out (2016, pp. 52–53), not all chimpanzees possess the capacities that ground legal personhood. Some chimpanzees are infants, others have mental disabilities, yet others are senile. If the NhRP were fully committed to the view that only the actual possession of certain mental capacities grounds legal personhood, then any being who lacks these capacities could not be a legal person—young, old, and mentally deranged chimpanzees included. Cupp furthermore argues that if the NhRP indeed held such a strict view, it would also follow that human beings with mental disabilities would not be legal persons. Let us now translate Cupp’s observations into the language of the spectrum I have been using. What Cupp is saying is that if the NhRP’s theory approximates the first element (differential consideration) of the naturalist ideal-type to too great an extent, then it can neither account for why chimpanzees who are infants, mentally disabled, or senile should be legal persons, nor for why humans with mental disabilities should be. The implicit point in Cupp is that the NhRP’s position would be more viable if it distanced itself somewhat from the naturalist ideal-type and incorporated, at least to some degree, the ideal of equal consideration of the interests of all members of the species Pan troglodytes (chimpanzees) and that of Homo sapiens. The NhRP could maintain its general naturalist position, according to which empirical facts about beings such as chimpanzees are crucial in recognising them as legal persons. However, to be more viable, it may want to found a norm that would include all chimpanzees and all humans, notwithstanding the fact that some of them may not possess the specific cognitive abilities that have propelled their species into the moral and legal limelight.

Now take the example of dignitarians such as Kateb and Waldron. Their approaches face the problem that certain human beings, like the profoundly mentally disabled, are far from being the kinds of moral and self-conscious agents that constitute the ideal subjects of their theories. Waldron (2012, pp. 49–50; 2017, p. 228), for example, places great emphasis on humans’ capacity for moral agency, while Kateb (2011, p. 11) focuses on humans’ ability to make self-conscious choices. Although they both try to downplay the challenge to dignity that human beings pose who are not agents and who cannot make self-conscious choices, the fact remains that these humans exist and that their existence sits uneasily with theories of dignity that set great store by agency or self-consciousness. Perhaps even more problematically, there are some nonhuman beings that are closer to being moral and self-conscious agents than human beings who do not possess those capacities. These empirical facts question the viability of dignitarian theories which interpret the principles of equality and dignity to encompass all and only human beings. In order to become more viable, these theories could approach reality by giving the abovementioned empirical facts increased moral and legal attention. This could be done, for example, by extending dignity and rights to a small category of nonhumans, such as ‘posthumans’, certain AIs, or other primates. In fact, it is this insight that I believe underlay the extension of aristocrats’ status and privileges to all human beings which Waldron advocates. This extension occurred among other reasons because it made no sense, empirically, to distinguish between ‘noble’ human beings and non-‘noble’ ones.

To put this point more generally: to improve the practical viability of their accounts, naturalists may sometimes want to take a step in the dignitarian direction, while dignitarians will sometimes want to make concessions to naturalism. Neither naturalist nor dignitarian theories are required to do so, of course. Individual accounts pursuing these ideal-types can choose to approximate their ideal to as great an extent as possible and thereby benefit from the respective advantages. The downside of this approach, however, is that they thereby also inherit more of the ideal-type’s inherent weaknesses (which is the same as to say that they lose out on the strengths of the other ideal-type).

With this in mind, I propose that a helpful way to understand debates between dignitarians and naturalists is as exchanges that move back and forth on the normative spectrum staked out by their ideal-types. To adapt John Rawls’s notion, we can speak of a kind of a reflective equilibrium. On the one hand there are empirical differences in the nature of beings that demand to be taken into account by normative principles. On the other hand, dignity and equality require the founding of groups that exclude consideration of certain differences. The most practically viable accounts will be those that—by ‘work[ing] from both ends’ (Rawls 1971, p. 20)—arrive at an equilibrium. As with Rawls’s reflective equilibrium, the reflective equilibrium between naturalism and dignitarianism is not a stable one. If new empirical findings question existing normative principles, then we have good grounds for reconsidering these principles; and if empirical differences are emphasised to too great an extent, then we have reason to found more exclusive normative principles.

This call for an equilibrium may strike some as a rather fainthearted proposal. Why be moderate if we can be radical? Why not try to escape the spectrum and reconstruct it fundamentally? In a polarised world, such suggestions will undoubtedly fall on sympathetic ears. The issue with these proposals, however, is that one cannot simply think or define away the antithetical phenomena that underlie the two ideal-types which I have presented. Put differently, even if we abandon the concept of the spectrum and the two ideal-types, the practices and beliefs on which they were based will subsist. Hence, while one is free to grasp the nettle, as it were, and adopt a strict naturalist or dignitarian approach, it would be illusory to hope that this is possible without also inheriting that approach’s practical problems. And while one can venture a fundamental reconstruction of the spectrum, it would be naïve to believe that this would coincide with a fundamental change of reality.

Conclusion

I have made two points in this article. First, that the central arguments of the ‘new’ dignitarians and their naturalist adversaries have already been voiced by dignitarians and naturalists in the French Enlightenment. Second, that understanding the reason for the similarity between arguments past and present (that is, the fact that they are representative of two opposed normative ideal-types) deepens not only our understanding of these arguments but also reveals a philosophical problem—the Zero-Sum Problem—which explains why conflicts between naturalism and dignitarianism are irresolvable. However, as I have shown, the Zero-Sum Problem also points to what individual theories have to do in order to become more practically viable: they have to find the right equilibrium between the two ideal-types.

Notes

It should be emphasised, however, that this is far from being the only approach to dignity. For a helpful overview of different dignity accounts, see Schroeder and Bani-Sadr (2017).

At least as long as there are no ‘posthumans’ or AIs that possess the same rights-grounding capacities that sane adult humans possess.

All translations are mine.

I am using the term ‘sensitive’, not ‘sentient’, to translate de la Métherie’s sensible. His usage of sensible is wider than the contemporary usage of ‘sentient’. While ‘sentient’ is often limited to the capacity to feel pain, and therefore to animals, de la Métherie also allows for the inclusion of plants in his definition of êtres sensibles (see the footnote in de la Métherie 1787, p. 199).

We owe our awareness of it to the French sociologist Valentin Pelosse who discovered the exchange in the 1980s and, more recently, to the historian Pierre Serna who dedicated an entire book to the exchange and its broader historical context (see Serna 2016).

Singer calls this the 'equal consideration of interests' principle. In contrast to dignitarianism’s equal consideration, however, Singer’s principle is not based on the assumption that the interest-holders have equal moral value. It is precisely for this reason that is has been criticised (see e.g. Regan 1985, p. 19).

I am grateful to Trevor Allan for pressing me on this point.

References

Albers, Marion, Thomas Hoffmann, and Jörn Reinhardt. 2014. Human Rights and Human Nature: Introduction. In Human Rights and Human Nature, ed. Marion Albers, Thomas Hoffmann, and Jörn Reinhardt, 1–10. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bodson, Liliane. 1983. Attitudes Toward Animals in Greco-Roman Antiquity. International Journal for the Study of Animal Problems 4(4): 312–320.

Brownsword, Roger. 2012. Bioethics Today, Bioethics Tomorrow: Stem Cell Research and the Dignitarian Alliance. Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy 17(1): 15–51.

Brownsword, Roger. 2014. Human Dignity, Human Rights, and Simply Trying to Do the Right Thing. In Understanding Human Dignity, ed. Christopher McCrudden, 345–358. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buchanan, Allen. 2011. Beyond Humanity? The Ethics of Biomedical Enhancement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carozza, Paolo G. 2014. Human Rights, Human Dignity, and Human Experience. In Understanding Human Dignity, ed. Christopher McCrudden, 615–629. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Caulfield, Timothy, and Roger Brownsword. 2006. Human Dignity: A Guide to Policy Making in the Biotechnology Era? Nature Reviews 7: 72–76.

Cochrane, Alasdair. 2012. Evaluating ‘Bioethical Approaches’ to Human Rights. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 15(3): 309–322.

Cochrane, Alasdair. 2013. From Human Rights to Sentient Rights. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 16(5): 655–675.

Cochrane, Alasdair, and Steve Cooke. 2016. ‘Humane Intervention’: The International Protection of Animal Rights. Journal of Global Ethics 12(1): 106–121.

Cupp, Richard L. 2016. Cognitively Impaired Humans, Intelligent Animals, and Legal Personhood. In Pepperdine University Legal Studies Research Paper No. 12, 3–55. http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2775288. Accessed 10 May 2018.

Dworkin, Ronald. 2011. Justice for Hedgehogs. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Dworkin, Ronald. 2013. Taking Rights Seriously. London: Bloomsbury.

Englard, Izhak. 2000. Human Dignity: From Antiquity to Modern Israel’s Constitutional Framework. Cardozo Law Review 21: 1903–1927.

Fukuyama, Francis. 2002. Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kateb, George. 2011. Human Dignity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kymlicka, Will. 2017. Human Rights Without Human Supremacism. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 1–30.

Leopold, Aldo. 1966. A Sand County Almanac. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

McMahan, Jeff. 2005. Our Fellow Creatures. The Journal of Ethics 9(3/4): 353–380.

McMahan, Jeff. 2008. Challenges to Human Equality. The Journal of Ethics 12(1): 81–104.

Métherie, Jean-Claude de la. 1787. Principes de la philosophie naturelle, dans lesquels on cherche à déterminer les degrés de certitude ou de probabilité des connoissances humaines. Vols 1 & 2. Geneva.

Métherie, Jean-Claude de la. 1802. De l’homme considéré moralement; de ses moeurs, et de celles des animaux. Vol. 1. Paris: Guilleminet.

Phillips, Anne. 2015. The Politics of the Human. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pollman, Arnd. 2014. Human Rights Beyond Naturalism. In Human Rights and Human Nature, ed. Marion Albers, Thomas Hoffmann, and Jörn Reinhardt, 121–136. Dordrecht: Springer.

Posner, Richard. 2000. Animal Rights. Yale Law Journal 110: 527–541.

Rachels, James. 1999. Created From Animals: The Moral Implications of Darwinism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rawls, John. 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Regan, Tom. 1985. The Case for Animal Rights. In In Defence of Animals, ed. Peter Singer, 13–26. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Rosen, Michael. 2012. Dignity: Its History and Meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rossello, Diego H. 2016. ‘To Be Human, Nonetheless, Remains a Decision’: Humanism as Decisionism in Contemporary Critical Political Theory. Contemporary Political Theory 16(4): 439–458.

Salaville, Jean-Baptiste. 30 Thermidor Year XIII. “À M. Foullière, Sur sa lettre contre l’ouvrage intitulé: De l’homme et des animaux.” La décade philosophique, littéraire et politique T46: 339–45.

Salaville, Jean-Baptiste. 1805. De l’homme et des animaux. Paris: Ch. Crapelet.

Savulescu, Julian, and Ingmar Persson. 2012. Moral Enhancement, Freedom and the God Machine. The Monist 95(3): 399–421.

Schroeder, Doris, and Abol-Hassan Bani-Sadr. 2017. Dignity in the 21st Century: Middle East and West. Cham: Springer.

Serna, Pierre. 2016. L’animal en République, 1789–1802: genèse du droit des bêtes. Toulouse: Anacharsis.

Singer, Peter. 1990. Animal Liberation. 2nd edn. London: Pimlico.

Smith, Justin E. H. 2015. Nature, Human Nature, & Human Difference: Race in Early Modern Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tasioulas, John. 2015. On the Foundations of Human Rights. In Philosophical Foundations of Human Rights, ed. Rowan Cruft, S. Matthew Liao, and Massimo Renzo, 45–70. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tribe, Laurence H. 2001. Ten Lessons Our Constitutional Experience Can Teach Us About the Puzzle of Animal Rights: The Work of Steven M. Wise. Animal Law 7(1): 1–8.

Waldron, Jeremy. 2012. Dignity, Rank, and Rights, ed. Meir Dan-Cohen. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Waldron, Jeremy. 2017. One Another’s Equals: The Basis of Human Equality. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Wikler, Daniel. 2009. Enhancement: Do Civil Liberties Presuppose Roughly Equal Mental Ability? In Human Enhancement, ed. Julian Savulescu and Nick Bostrom, 341–355. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Nigel Simmonds, Trevor Allan, John Adenitire, Ya Lan Chang, Yukinori Iwaki, Crescente Molina, Joshua Neoh, and the two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. Special thanks are owed to Will Kymlicka for his insightful remarks on my Ph.D. work which has inspired this article. My research was made possible by a scholarship from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fasel, R.N. The Old ‘New’ Dignitarianism. Res Publica 25, 531–552 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-018-09411-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-018-09411-2