Abstract

This study examines whether there is a relationship between religiosity and voluntary disclosure quality (VD_Q). We utilise a three-dimensional approach to capture the VD_Q on an international sample of 1,484 bank-year observations in 12 countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region over 14 years period from 2006 to 2019. Our findings indicate that religiosity is positively associated with banks' VD_Q. Our findings also show that the association between religiosity and VD_Q is more noticeable in banks operating in countries with a low level of legal protection, low level of control of corruption and during the crisis period. We further illustrate that the influence of religiosity is more intense on the spread and usefulness of information dimensions than the quantity dimension. These empirical findings are robust to alternative proxies of religiosity and sample specification. This result supports the notion that religiosity enhances corporate disclosure quality and reduces the asymmetric information gap between managers and outside users of information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, academics have drawn attention to the effectiveness of informal institutions in influencing managerial practices (North 1990) since they complement formal institutions when they are less effective. Prior studies document evidence that suggests the role of the non-conventional institution in various organisational outcomes (Lins et al. 2017; Anginer et al. 2018; Qian et al. 2018).

One key informal institution that has captured the attention of researchers is religiosity (Vitell 2009, Cantrell and Yust 2018, Chircop et al. 2017, Cui et al. 2019, Abdelsalam et al. 2020, Hilary and Hui 2009, Chen et al. 2020). For instance, a recent survey finds that almost 84% of the world population are classified as belonging to a particular faith or holding a religious belief (Sherwood 2018). The increasing relevance of religion is due to its influence on cultural (moral) values and ethical considerations in a business context (Hilary and Hui 2009; Abdelsalam et al. 2021). Social norm theory (Kohlberg 1984) suggests that cultural norms that favour morality and aversion to risk are developed when a high proportion of people adhere to religious values. These norms will drive the values and behaviour of groups and individuals.

Extant literature has documented the impact of religiosity on managerial behaviour (Kutcher et al. 2010; Vitell 2009; Ma et al. 2019; Hilary and Hui 2009). Abdelsalam et al. (2020) argue that religious norms influence a manager's sense of shame or guilt, resulting in a more accountable and ethically informed decision. Weaver and Agle (2002) find support for a strong influence of religiosity on an individual or group's decision. Similarly, Mazar et al. (2008) show that the likelihood of dishonest reporting is reduced when a moral code of conduct guides the actions of individuals.

The main objective of this study is to test whether there is a variation in banks' voluntary disclosure quality in countries where adherence to religious norms is more pronounced and is part of cultural and national identity. This objective is vital since prior studies suggest varying impacts of religious norms across different countries (Leventis et al. 2018; Kanagaretnam et al. 2015) and differences in a country's adherence to religious norms and institutional governance qualities (Chen et al. 2016). Specifically, studies on voluntary disclosure have also acknowledged differences across national boundaries (Zarzeski 1996; Jaggi and Low 2000). Therefore, this study examines the relation of religiosity to the voluntary disclosure of banks in 12 Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries. Our research is interesting since these banks operate in countries with Islam as part of their national identity. Although different religions exist in some MENA countries, Islam is still the dominant religion (Abdelsalam et al. 2021). Platonova et al. (2018) and Asyraf Wajdi (2008) demonstrated that the ontological and epistemological principles of Islam alter managers' behaviour, indicating that religion has a considerable impact on managers' behaviour. Firms in MENA countries are strongly influenced by Islamic religious principles, regulations and values derived from “Shariah”—the Islamic law. All Muslims are obliged to follow Shariah, which provides guidance on various aspects of life of Muslims. Since Islam is the dominant religion in the MENA region, this study assumes its influence in moral behaviour and ethical standards that underpins business activities. For example, firms in MENA region are expected to operate on the basis of a transparent and ethical manner along the criteria of justice, equity, and Ihsan (benevolence) (Hassan and Harahap 2010). Therefore, these Islamic countries provide an ideal setting to examine the impact of religiosity on the voluntary disclosure of banks.

We are motivated to examine the impact of religiosity for the following reason. First, previous studies on voluntary disclosure have not paid attention to firms' religious environment. Previous literature has documented the need for voluntary disclosure (Leuz and Verrecchia 2000). Voluntary disclosure supplements mandatory disclosure (Graham et al. 2005). One of its main aims is to reduce the information asymmetry between principal and agent (Myers and Majluf 1984). The existing studies have identified several factors that affect managers' disclosure decisions such as corporate governance, firm characteristics, managerial behaviour and institutional environment (Abdelsalam et al. 2021; CUI et al. 2015; Healy and Palepu 2001). However, few studies explore the relationship between religiosity and the quality of voluntary disclosure. Particularly, managers of banks operating in MENA countries have high discretion on the choice of voluntary disclosures' content (Piesse et al. 2012). Although the economic consequence of a firm's voluntary disclosure is well documented (Leuz and Verrecchia, 2000), extant literature has focused on corporate governance, firm characteristics and managerial behaviour and institutional environment (Cantrell and Yust 2018; Core 2001; Callen and Fang 2015; Chen et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2020; Gokcekus and Ekici. 2020).

Secondly, studies suggest that religiosity influences the ethical standard of managers and has a positive impact on their moral choices (Parboteeah et al. 2008; Cui et al. 2015; Leventis et al. 2018) and risk attitude (Chircop et al. 2017; Cantrell and Yust, 2018; Adhikari and Agrawal, 2016). Research also shows that firms that operate in a religious environment are more likely to engage in ethical behaviour (McGuire et al. 2012; Hilary and Hui 2009). Thus, it is expected that religiosity will promote honesty and higher moral standard among managers, thereby influencing their voluntary disclosure quality. The chosen sample in our study has distinctive cultural features. Religion substantially affects their managers' behaviours, especially in the banking sector (Asyraf Wajdi 2008). Mangers' behaviours are shaped by Islam's ontological and epistemological sources (Platonova et al. 2018).

Third, our study focuses on banks that are considered one of the key pillars of every financial system but have received limited attention from earlier studies (Jizi et al. 2014). This study is relevant and ensures the integrity of the financial system of MENA countries by examining banks' disclosure quality. Furthermore, Levine (2004) argues that the complexity of banks transcends that of non-financial firms due to their role in the allocation and mobilisation of funds and their impact on overall national productivity.

Against this backdrop, our study examines the impact of religiosity on voluntary disclosure quality using 1484 bank-year observations in the 12 Middle East and North African (MENA) countries over 14 years. Consistent with Hilary and Hui (2009), we considered banks with their headquarters in any MENA country since the policies that guide a business are made at corporate headquarters. Unlike previous studies that examine the quantity of voluntary disclosure, this focused on the quality of voluntary disclosure using a three-dimensional approach. To ensure the robustness of our result, we isolated the influence of bank characteristics, corporate governance environment, institutional and macroeconomic factors.

Using three proxies on religiosity, we document a positive relationship between religiosity and voluntary disclosure quality. We also found that the influence of religiosity is more on the spread and usefulness of the information dimension compared with the quantity dimension. Our result also shows that the association between religiosity and VD_Q is stronger for banks with headquarters in MENA countries with weaker legal protection, low level of control of corruption and during the crisis period. Additionally, we found that the influence of religiosity is more robust on the spread and usefulness of information dimensions than the quantity dimension.

Overall, we find evidence that religiosity enhances the voluntary disclosure quality and minimises the information gap between insiders (managers) and other users of firms' information. We conducted an additional analysis using an alternative proxy of religiosity and found a positive impact on banks' disclosure quality.

Our study makes significant contributions to the disclosure literature in the following ways. First, we provide evidence that informal institution (religion) influences the disclosure quality of banks in developing economies. Our result contributes to previous studies on how informal institutions influence various organisational outcomes (North 1994). Secondly, this study has extended the ongoing debate on the relationship between religiosity and corporate disclosure practice. Additionally, we show that the interaction between the formal institution and religiosity positively impacts firms' disclosure quality. We also contribute to the debate on the influence of religiosity during the financial crisis. Our contribution is important to bank managers and policymakers since it helps them understand factors influencing the quality of disclosure in MENA regions.

2 Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1 Background, social norms and banks' disclosure quality

Although IFRS has become mandatory in MENA region, it still allows managers to use discretion when disclosing information.Footnote 1 Our rationale for connecting religiosity and voluntary disclosure quality is based on previous literature. Hambrick and Mason’s (1984) upper echelons theory suggests that differences in managers' important personal values and cognitive styles could result in differences in behaviour. Previous studies also indicate that managers’ personal values and interests are important factors for firms’ disclosure decisions (e.g. Ba et al. 2013; Di Giuli and Kostovetsky 2014; Hemingway and Maclagan 2004; Rubin, 2008). Similarly, agency theory suggests that voluntary disclosure aims to mitigate conflict of interest between agents and principles (Dye 1985). In line with signalling theory, insiders of business should endeavour to convey information to less informed parties to decrease information asymmetry (Connelly et al. 2011; Shroff et al. 2013). Therefore, an ethical manager is expected to provide high-quality voluntary disclosures to reduce information asymmetry. Religion has been considered a source of ethical behaviour that will affect managers’ disclosure. Social norms literature argues that religions establish a set of principles and thereby shape human ethical behaviour (e.g. Du et al. 2014a, b; El Ghoul et al. 2012; Weaver and Agle 2002). We argue that religiosity will influence managers’ behaviours in relation to voluntary disclosures.

Voluntary disclosure transcends compulsory "regulated" disclosure requirements. It demonstrates managers' free choices to report information that is considered more relevant to assist users of the annual report in making a better decision (Salem et al. 2020). Interestingly, an increasing number of banks operating in the MENA region have started reporting more information voluntarily to signal their overall strategy (Elamer et al. 2020a, b). Dhaliwal et al. (2011) and Patten and Zhao (2014) indicated that voluntary disclosure attracts the interest of investors and other socially responsible parties because it is instigated by the ethical disposition of firm management and the significance of responsibility towards communities.

Sociologists have widely studied social norms to explain social behaviours and social order. Durkheim (1965) argues that social norms are the unwritten rules or patterns of behaviour in a certain group, where there is an agreement on how appropriate behaviour can be interpreted ontologically. The theory of social norms forms the basis for evaluating behavioural patterns surrounding rewards and sanctions (Leventis et al. 2018; Weaver & Agle, 2002). In a conceptual framework, religiosity is considered the main type of social norm. It refers to the extent people support the same set of principles of religious beliefs, values, and promulgations. Psychology literature has advocated that religion significantly affects human behaviours (e.g., Eriksson 2015). Prior research provides evidence that religiosity and moral behaviours are closely linked (Glover 1997; Sapp and Gladding 1989; Vitell 2009). They argue that religion constructs a set of principles and thereby provides frameworks for ethical business behaviour (Weaver and Agle 2002; Epstein 2002; Melé and Fontrodona 2017).

Previous research mainly focuses on investigating the relationship between religiosity and financial reporting quality (Abdelsalam et al. 2021; Adhikari and Agrawal 2016; Cantrell and Yust 2018). Managers in religious areas are more willing to avoid irregularities in their financial reporting (McGuire et al. 2012). Empirical evidence shows that religiosity is negatively associated with the level of accounting manipulation (Conroy and Emerson, 2004). Longenecker et al. (2004) find that religious practitioners and business managers are less likely to make unethical judgements and decisions. Additionally, Oh and Shin (2020) indicated that religious beliefs motivate individuals to enhance values and morality, which in turn improves social trust. Callen and Fang (2015) found that religiosity is associated with lower levels of future stock price crash risk since religion is considered as a set of social norms that leads to restraining bad news-hoarding activities by managers. Furthermore, firms located in religious countries are more likely to avoid risk-taking to ensure stable financial performance (Hilary and Hui 2009; Swaen and Chumpitaz 2008). Particularly, in the banking industry, CEOs that hold religious beliefs are more likely to engage in risk aversion (Adhikari and Agrawal, 2016; Chircop et al. 2020). Recent research has attempted to explore how religiosity affects disclosure quality. For instance, Dyreng et al. (2012) provide evidence that religion has an impact on managers' decisions in various contexts. They argue that firms' managers who reside in religious areas are more likely to voluntarily disclose negative information in a timely fashion. Moreover, Du et al. (2014a, b) found that religiosity has a significantly positive relationship with disclosure scores in Chinese listed firms. This result supports the view of religiosity as a type of social norm. Therefore, managers located in the stronger religious area are more likely to be influenced by such norms (Kennedy and Lawton 1998), and less likely to engage in unethical decisions such as accounting manipulation (Callen and Fang 2015; Dyreng et al. 2012; Hilary and Hui 2009).

Nevertheless, there is a possibility that firms in the religious area are less likely to be monitored since they are assumed to have higher morals (Gokcekus and Ekici 2020). This less monitoring will create more discretion for managers. Therefore, firms’ managers may focus less on actions that benefit other stakeholders, such as releasing high-quality disclosures. Given the concerns about the cost of disclosures (Barnea and Rubin 2010; Grougiou et al. 2016; McWilliams and Siegel 2001), issuing a perfectly credible or, equivalently, completely unbiased disclosure might not be an optimal choice for the firm (Core 2001). Organisational strategies and attitudes will be affected by religious beliefs because managers interact with local contexts and populations (McGuire et al. 2012). Religiosity mitigates opportunistic behaviour (Callen and Fang 2015) and enhances ethics in business (McGuire et al. 2012). Prior studies link religiosity with moral judgment (Walker et al., 2012). Even Irreligious managers might be affected by religious norms in the local area as they tend to avoid the costs of rejecting religious norms (Cialdini and Goldstein 2004; Sunstein 1996; Kohlberg 1984; Le Bon 2002). Religion shapes peer behaviour and promotes appropriate corporate ethical decisions and practices (Weaver and Agle 2002). Empirical evidence supports that religion plays a significant role in corporate governance, and curbs bad news-hoarding activities by managers (Callen and Fang 2015; Dyreng et al. 2012; Leventis et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2014; Baik et al. 2018).

Religions are assumed to be a source of morality (Geyer and Baumeister, 2005). Consequently, religiosity has an impact on people's level of acceptance of unethical accounting choices (Conroy and Emerson 2004; Longenecker et al. 2004). We expect that religious norms will positively affect managers' disclosure decisions in the banking industry. Chantziaras et al. (2020) support this conjecture by providing evidence of a positive relationship between religiosity and the extent of disclosure in the banking system. The banking industry is often categorised as an industry with significant uncertainty and opacity (Furfine, 2001) because of the complexity and diverse nature of its business (Heilpern et al. 2009). In line with the agency theory, a high disclosure quality will reduce information asymmetry (Brown and Hillegeist, 2007). Therefore, we expect that managers with religious beliefs will disclose more information voluntarily, which reduces information asymmetry and assist users in making better decisions. Collectively, we make the following hypothesis:

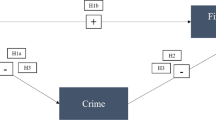

H1

Religiosity is positively related to voluntary disclosure quality.

2.2 Religiosity, formal institutions and banks' disclosure quality

The modern business system was developed based on agency theory; hence information asymmetry inherently exists between the principals and agents (Fields et al. 2001). Formal institutions introduced rules and regulations aimed to reduce information asymmetry. They help structure and regulate the economic order and business activities so that the investors' rights can be protected and unethical behaviour, such as accounting manipulation, can be prevented.

Prior studies find that firms in a less strict legal environment are more likely to be involved in accounting manipulation (Cohen et al. 2008; Wang and Campbell, 2012; Zeng et al. 2012; Xie et al. 2003). Notably, previous studies suggest a strong association between governance system and disclosure quality (Yong and Thyil 2014). North (1990) suggests that the informal institutions' role in accounting disclosure quality is stronger in the weaker institutional settings. He proposes that informal institutions are considered as a result of social consensus and argues that customs, cultures, and ideals are unconsciously formed as a set of undocumented codes. These factors are entwined with religion and accepted as social norms. Moreover, it is eventually spread and inherited generation by generation (Tonoyan et al. 2010). Human behaviours will be unconsciously influenced by this set of beliefs that are informally institutionalised (Pearce 2013; Bruton et al., 2005).

In addition, studies have documented the influence of formal institutions on managerial practices (e.g., Cheng et al. 2020). When the formal institutions are strong, firms are more willing to comply with the framework, rules or regulations to avoid costs and sanctions. In this regard, Chen et al. (2016) found that religiosity has a significant and positive association with higher business ethics, risk aversion, and low cost of debt. Religiosity plays a major role in restricting opportunistic behaviour in a weaker legal environment. Cantrell and Yust (2018) found that religiosity is linked to fewer failures, higher ROAs and lower earnings manipulation in the banking sector. However, when formal institutions are weak, informal institutions will guide managers' ethical behaviour. In the context of disclosure quality, religiosity is expected to have a positive association with disclosure quality. One aim of disclosure is to mitigate information asymmetry (Chen et al. 2020). An ethical firm's manager is more likely to disclose more useful information that helps users in their economic decision-making. This notion is consistent with Helmke and Levitsky (2004), who claimed that the relationship between formal and informal institutions relies on the effectiveness of the actors' target in the institutions. Collectively, religiosity is complementary to weak formal institutions (Horak and Yang 2018). Consistent with these arguments, we make our second hypothesis as follows:

H2

The association between religiosity and voluntary disclosure quality is more pronounced in countries with weak formal institutions.

2.3 Religiosity, crisis and banks' disclosure quality

The 2008 financial crisis was the darkest time for most businesses in the world in the past two decades. Particularly, banks were in the middle of a storm and experienced bankruptcy, stock crashes, and dramatically increased liabilities with a lack of support from the state (Hawtrey and Johnson 2010).

A significant number of works have explored the accounting manipulations during financial crises. One stream of empirical evidence shows that managers are more likely to engage in accounting manipulation during the financial crisis for personal incentives (Ahmad-Zaluki et al. 2011; Türegün 2020). They fully take advantage of managers' discretion given by the flexibility of accounting standards (Gorgan et al. 2012). Earlier studies show that the choice of content in voluntary disclosure relates to managerial strategic decisions (Dye 1985; Li et al. 1997) and incentives (Bewley and Li 2000). Prior research finds an increase in accounting manipulations during the financial crisis (Salem et al. 2020). Balasubramanyan et al. (2014) investigated annual reports of 469 commercial banks listed in 27 EU countries from 2005 to 2010 and found an increase in manipulations of loan loss provisions. In addition, Bornemann et al. (2012) analysed annual reports of German banks from 1997 to 2009. The study examined the extent to which insiders built hidden reserves to avoid a fall in earnings. They find an increase in the manipulation of accounting numbers as a result of bankers offsetting less favourable returns caused by the financial crisis. Furthermore, Abdelsalam et al. (2017) found that managers are more likely to engage in accounting manipulation to maintain consistently favourable performance in different periods, even if it is during a financial crisis. Those findings align with agency theory, which proposes that interest conflicts can be present because of information asymmetry (Kothari 2001; Schipper 1989).

In contrast, another stream of the literature shows contradictory results. For example, Filip and Raffournier (2012) investigated accounting manipulation during the 2006–2009 financial crisis. They interestingly find that the quality of financial disclosure increased over the crisis year. During a crisis, firms' managers are more likely to disclose high-quality information to attract potential investors (Cimini 2015). High-quality disclosure promotes trust between a firm, its stakeholders and investors during the most challenging time (Lins et al. 2017). The banking industry has been considered an essential element of the global economy (Scholtens 2009; Grougiou et al. 2016). Therefore, many stakeholders are interested in monitoring banks' sustainability, operation, and social contribution (Mehran et al. 2012). The whole industry is highly regulated by authorities and vigorously followed by the media, financial institutions, and various committees (Adhikari and Agrawal 2016). Banks will consider the general business environment when making strategic decisions (Jiang et al. 2018). It is rational that the banks' managers tend to provide high-quality disclosure during the crisis because of specific incentives whether they are religious or not.

Interestingly, in the context of religiosity, psychological studies suggest that religious people can easily deal with significant life events (McDougle et al. 2016). People maintaining spiritual stability benefit from their beliefs and religious community (Halikiopoulou and Vasilopoulou 2016; Orman 2019). Studies find that Islamic banks could sustain operations through the crisis, and that they performed better than conventional banks during crisis (Rosman et al. 2014; Parashar 2010). Díez-Esteban et al. (2019) find that religion is beneficial to individuals to maintain tranquillity during the financial crisis. Few studies explore how religious managers make decisions about firms' voluntary disclosure during a crisis period. Religion motivates adherents to ensure their behaviour is consistent with role expectations (Sunstein 1996; Weaver and Agle 2002). In line with Stewardship theory (Davis et al. 1997), managers are expected to protect and maximise shareholders' wealth, especially during a crisis. Consistent with this argument, it seems that religion will help bankers to remain ethical during the financial crisis. However, given the aforementioned argument regarding the disclosure incentives, we prudently give our non-direction hypothesis as follows:

H3

The association between religiosity and voluntary disclosure quality is more or less pronounced during crisis periods.

3 Research design

3.1 Sample selection procedure

We gathered the financial data from DataStream and Osiris databases. We hand-collect the voluntary disclosure quality (VD_Q) from each bank's annual reports. The religiosity proxies and the macro-economic variables were obtained from World Values Survey (WVS) and the World Bank, respectively. To test our hypothesis, the sample is constructed based on all conventional banks that are publicly listed and operating in MENA countries. Even though certain MENA countries have multiple religions, Islam is the dominant religion (Abdelsalam et al. 2021). As a result, these Islamic countries present an excellent scenario to investigate the relationship between religion and banks’ voluntary disclosure. Although there is a slight difference in religiosity across MENA countries, it is usually confounded by a country's institutional and legal characteristics, which are difficult to be disconnected from religion. The conventional banks in MENA countries offer a more controlled and dynamic setting which is appropriate to examine our hypotheses. Following Pirinsky and Wang (2006), we used banks' headquarters as they are close to the bank's main financial activities. Our sample is limited to banks that report tier 1 capital ratios to guarantee that the analysis is not unduly affected by the variances in regulatory environments and non-comparable business practices. Islamic banks were excluded since they have other regulatory requirements than commercial banks. As a result of the late employment of IFRS by most banks in the MENA region in 2006, we filtered the sample by covering pre- and post-banking crisis. This study considers the annual data over 14 years from 2006 to 2019. We omitted 21 banks from the sample due to insufficient and missing financial information. Based on the above implications and our data specification, our sample is limited to 12 MENA countries.Footnote 2 Our final sample translated into 1,484 bank-year observations for our empirical analyses (see Appendix IV).

3.2 Religiosity measurement

Following previous studies (Abdelsalam et al. 2021; Kanagaretnam et al. 2015; McGuire et al. 2012; Parboteeah et al. 2008), we define religious norms adherence using three different dimensions, (a) Cognitive dimension (RP),Footnote 3 which focus on religious knowledge or beliefs, (b) Affective dimension (RI)Footnote 4 that takes into account the feelings of individuals about religion, and (c) Behavioural dimension (RAS),Footnote 5 which highlights the attendance of religious services, prayer or constant donations. Utilising data from the World Values Survey (WVS), we collect and calculate the strength of the three religiosity dimensions. Therefore, we considered the responses to questions about the importance of religiosity, religious affiliation, and the attendance of religious services. We used the aggregate religiosity measure (Aggregate-REL) of the three religious' dimensions as our main variable of interest.

3.3 Quality of voluntary disclosure measurement

Following Salem et al. (2020), we gathered and measured the quality of disclosure by classifying the information into three dimensions that cover both quantitative and qualitative features of information. These dimensions are quantity, spread, and usefulness.

-

(A)

Quantity Dimension

This dimension takes into account the level of information (quantity), and is adjusted by bank size as it has a direct influence on the business operation (Beretta and Bozzolan, 2008; Rezaee and Tuo, 2019). We employed the content analysis method collaboratively with a comprehensive index that contains relevant voluntary disclosure items (see Appendix I).Footnote 6 Therefore, we adjusted the total number of words by bank size and utilised it to capture the level of information disclosed voluntarily. Following prior studies (e.g., Beretta and Bozzolan, 2008; Salem et al. 2020), we used OLS regression to estimate the proxy of quantity dimension (QS_TR). Below is the standardised equation:

where: QS_TRit = standardised relative quantity index for the bank i at year t. R_Qit = is the relative quantity index, which is the residual for the banks i at year t that was obtained after controlling the size of the bank.

-

(B)

The Spread Dimension

The second dimension focuses on the coverage (CO_VE) and dispersion (DI_SPE) of the disclosed information to satisfy numerous stakeholders. The ratio of information disclosed (items) from the overall number of items in the checklist is used as the coverage proxy. On the other hand, the dispersion (DI_SPE) of items provided in the annual report within the disclosure checklist is employed to specify the concentration. Identifying the coverage and dispersion of information is adopted to capture whether bank managers offer a comprehensive and wide range of information or emphasis only certain items within the checklist. We used the below formulas to measure the dispersion and coverageFootnote 7:

where; H-j = is the ratio of revealed item i captured by the item disclosure frequency in category j. IN_F = 1 if bank i revealed information about item j and 0 otherwise. s is the number of subcategories. Accordingly, we used the average of DI_SPE and CO_VE as a proxy for the spread dimension:

-

(C)

The Usefulness Dimension

The third dimension takes into consideration the qualitative characteristics of IFRS (understandability, comparability, faithful representation, relevance and timeliness) (IFRS 2010). To collect and measure the dimension of usefulness, we employed five points rating scales index of Salem et al. (2020) (see Appendix II). Nevertheless, timeliness is gained using the natural logarithm of the number of days between the auditor's signature and the year-end. To ensure reliability and consistency, we employed the weighted technique of the qualitative characteristics suggested by Alotaibi and Hussainey (2016) and Salem et al. (2020). The following is the formula used to capture the usefulness dimension:

To achieve the quality of information revealed (VD_Q), we utilised the following equation:

Following Salem et al. (2020) and Lemma et al. (2020), we assess the validity of our measurement through several steps. First, the checklist was based on relevant research studies, an analysis of international trends and observations of standard reporting practice. Consequently, all disclosed items are appropriate, relevant and revealed by banks. In addition, we checked the reliability of our measurement by using several coders to score the research instrument (Alotaibi and Hussainey 2016). Following Salem et al. (2020), we also compared and resolved variances between coders accordingly.

3.4 Control variables

We specify several control variables at the bank and country levels. Following Du et al. (2014a, b), McGuire et al. (2012) and Sahyoun and Magnan, (2020), Usman et al. (2022), we have taken into account the auditing quality proxies (Big4, IA_C, AC_S, AC_M and AC_G), which may have a potential influence on enhancing the quality of disclosed information and its association with religiosity (Adhikari and Agrawal, 2016). In the face of contradictory aims and varying degrees of desire, Hambrick and Mason (1984) indicated that managers make business decisions not only on a logical analysis of techno-economic considerations but also on their personal beliefs and cognitive underpinnings. Previous literature found that managers’ effects are linked to companies’ policies (Bertrand and Schoar 2003), voluntary disclosures (Bamber et al. 2010) and tax avoidance (Dyreng et al. 2010). In this context, Salem et al. (2020) and Abdelsalam et al. (2021) indicated that managerial actions have an impact on the quality of corporate disclosure, and religion offers emotional support and consistency in managerial decision-making. Following Liu and Zhou (2020), we employed executives-gender to control for managerial effects. Previous studies argued that gender influences the presentation style of disclosure (Davis et al. 1997; Marquez-Illescas et al. 2019). In addition, other studies have documented the relationship between executives-gender and corporate financial reporting decision-making (Francis et al. 2015).

We include the governmental (G-Owner) and institutional (I-Owner) ownerships. These variables are expected to have a potential impact on the association between disclosure quality and religiosity. Institutional investors may stimulate managerial behaviour to be involved in unethical practices such as earnings management, thereby extending the asymmetric gap between other investors and the bank (Salem et al. 2020). In addition, Ghazali (2007) indicated that the activities of government-owned banks are more likely to be visible in the public eyes as they are expected to be conscious of their public duty. Therefore, government-owned banks tend to disclose extensive information to increase the level of trust and meet the expectations of their stakeholders. To control for the cross-sectional variances in bank characteristics, we counted in a set of several bank-level variables, which may affect the disclosure quality in the financial institutions. Following previous studies (Abdelsalam et al. 2021; Kanagaretnam et al. 2015; Salem et al. 2020; Core 2001), we isolated the effects of liquidity, capital adequacy ratio, profitability, growth, leverage and bank size.

Consistent with Chen et al. (2016), we also controlled for macro-economic conditions by including the log GDP per capita (L-GDPPC) as individuals' wealth may influence their utility function and values. In order to isolate the impact of religion from the influence of other country characteristics, we control for corruption value (C-Corruption) and legal rights index (Legal-Prot) to proxy for bank environment and investor protection (Kanagaretnam et al. 2015). These two variables are more likely to provide meaning over time and ensure cross-country comparisons (Kaufmann et al. 2011). Following Abdelsalam et al. (2016), we control for the potential impact of countries experiencing politicalFootnote 8 problems (P_T) from 2011 to 2019. we present the details of these variable definitions and measurements in Appendix III.

3.5 Empirical model

Our study model specification is built based on prior studies (e.g., Abdelsalam et al. 2021; Kanagaretnam et al. 2015; McGuire et al. 2012) and attempts to investigate whether religiosity is associated with voluntary disclosure quality in banks across 12 emerging countries. The following is the module usedFootnote 9 for the whole sample:

To ensure consistent estimation, we have used the Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) and Panel regression. Using GMM estimators is appropriate for resolving any possible bias in a dynamic panel (Arellano and Bond 1991; Roodman 2006). GMM estimator has been adopted in several recent corporate studies (Alhazaimeh et al. 2014; Holtz-Eakin et al. 1988; Issa et al. 2021; Kouki 2021; Ezeani et al. 2022). Additionally, the GMM estimator is designed for datasets with few periods and many explanatory variables that are less likely to be strictly exogenous and correlated to current realisations of the error (Kim et al. 2014; Ezeani et al. 2021). Following Blundell and Bond (1998) and Dhaliwal et al. (2011), we utilised two-step GMM as it enhances estimates efficiency by eliminating issues resulting from weak instruments and avoiding proliferation.

The procedure of the dynamic modelling approach involves two vital steps. Firstly, we use the dynamic model (7) in the first-differenced form to eliminate any possible bias that may arise from potential omitted variables and time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity. Secondly, we incorporated the lag values of explanatory variables into the GMM system and used them as instruments. These lagged values are expected to overcome the potential endogeneity concerns by transforming the data internally, where a variable's value of the previous year is subtracted from its current value (Roodman 2006). Consequently, we used historical values of religiosity, audit quality, banks’ ownership and country specifics variables as instruments. Following Wintoki et al. (2012), we used one-year lagged values of our explanatory variables. These variables are uncorrelated with the error term in the main model (7) and are considered valid instruments. Besides, the Arellano-Bond test and the Hansen test are used to assess the validity of the dynamic GMM estimator and whether the used instruments are specified appropriately. The findings of these tests appeared insignificant, suggesting that our instruments are exogenous; hence, valid and the dynamic GMM model is an appropriate estimation to tackle the likelihood of endogeneity concerns.

In addition, we used the Chow test to compare panel and pool regression. Our result indicates that the F statistics is highly significant at (0.001) for the overall sample, suggesting the appropriateness of panel data regression. Following Hedges and Vevea (1998), we used the Hausman specification test to investigate the appropriateness of fixed (bank-year effects) and random-effects regressions. We found that the fixed effects (untabulated) is the most appropriate for our dataset due to the significance of Prob > Chi2 = 0.002. The fixed effects technique can eliminate the impacts of confounding factors without having to measure or even know what they are, as long as they are constant across time (Firebaugh et al. 2013).

4 Baseline results and discussion

In Table 1, we provide the descriptive statistics of the variables involved in the analysis. The mean value of VD_Q (our dependent variable) indicates that the average of quality- information disclosed by banks is 61%, with a maximum value of almost 77% compared with all banks operating in the same region. This finding is close to those reported by Lim et al. (2017), who found that the average quality of information is around 58% among firms listed on the Australian stock exchange. However, our finding is higher by 40% compared with those reported by Ghosh (2018). This variance could be attributed to the measurement approach of disclosure implemented and to the period examined, which covers the post- Basel II adoption period in the MENA region (Elnahass et al. 2014).

In addition, the mean values of religious dimensions (RAS, RI and RP) are 29, 79 and 68%, with maximum values of 83, 97 and 94%, respectively. These findings suggest that the respondents highly recognise the importance of the religious dimension compared to the other dimensions. Most importantly, the mean and median values of the aggregate proxy for religiosity (Aggregate-REL) are 0.58% and 0.55%. This result is consistent with Adhikari and Agrawal (2016). Regarding the audit quality proxies, the mean values of Big-4, IA_C, AC_S, AC_M and AC_G are 60%, 52%, 3, 4 and 4%, respectively. These outcomes are in line with previous studies (D'Amato and Gallo, 2017; Salem et al. 2020, 2021). In addition, the bank and country-control variables seem to be insensible ranges and align with prior studies (e.g., Abdelsalam et al. 2021; Kanagaretnam et al. 2015).

Table 2 (Panel A) shows the correlation analyses among the study variables. This analysis illustrates that the highest correlation is between leverage and growth and is below the cut-off point (80%) suggested by Gujarati and Porter (2009). Since the coefficients of all variables are below 80%, the multicollinearity issue does not exist in our study. Additionally, the variance inflation factor (VIF) test shows that the condition index is lower than 5. Table 3 (Panel B) confirms that the likelihood of a multicollinearity problem between the explanatory variables is below the conventional threshold.

Table 4 provides the results of the impact of religiosity on disclosure quality using both fixed effects and GMM regressions. Regarding the main variables of interest (i.e., VD_Q and Aggregate-REL), Columns 1 and 5 of Table 4 shows that religiosity has a significant and positive influence on disclosure quality at a 1% level after employing several control variables at the bank-level and country level. Therefore, we accept H1. These findings align with the argument that bank managers with religious beliefs promote appropriate corporate ethical decisions and practices (Leventis et al. 2018). One possible explanation is that these managers avoid risk-taking to ensure stable financial performance (Hilary and Hui 2009; Chircop et al. 2020) and are more likely to provide more information voluntarily (Dyreng et al. 2012). In addition, Big-4 and IA_C, as proxies of audit quality, positively impact the quality of information disclosed by banks. The result is significant at 1% levels in both Fixed and GMM models, respectively. Based on the fixed-effects model, the Growth, G-OWNER and LI_Q have a positive and significant association with VD_Q at 1% and 5%, respectively. This result suggests that governmentally owned banks with a high level of growth are more likely to disclose high-quality information to increase the level of trust and meet the expectations of their stakeholders (Ghazali 2007). The rest of the control variables have the predicted sign.

To test our second and third hypotheses, we examine the influence of religiosity on VD_Q in two different forms, including; (1) across banks that are operating in a low legal protection environment and low level of control of corruption (H2), (2) during the period of the financial crisis (H3). Following Qian et al. (2018), we employed the legal rightsFootnote 10 and control of corruption indexes to gain each country's legal protection strength and corruption level. The median values of the legal protection and control of corruption are used as a cut-off point to generate proxies for "REL*Low-legal-prot" and "REL*Low-C-Corruption". The value of one is given to those banks that operate in a low legal protection environment and low level of control of corruption and zero otherwise. Table 4 Columns (2,3, 6 and 7) illustrate that the interaction terms of REL*Low-legal-prot and "REL*Low-C-Corruption are positively and significantly related to VD_Q at 1% levels in both models. This result indicates that the influence of religiosity on the quality of information revealed by banks is more prominent in countries with a low level of legal protection and a low level of control of corruption. This evidence confirms that unofficial institutions have a greater impact in regions where official institutions are less efficient (Abdelsalam et al. 2021; Qian et al. 2018). Therefore, we accept (H2).

We also generate an indicator "REL*Crisis" to examine whether the impact of religiosity on VD_Q differs over time, especially during the financial crisis. An indicator is used to test our hypothesis (H3). We also employed a Crisis variable which takes the value of one for the crisis period (2007–2009) and zero otherwise. Table 4 Columns (4 and 8) report that the interaction term REL*Crisis is positively and significantly linked to VD_Q at 1% levels in both models, suggesting that the influence of religiosity is stronger during the period of turmoil and recessions. This result is in line with the notion that religion provides emotional support and consistency in managerial decision-making during a crisis. Our result is consistent with previous studies (Abdelsalam et al. 2021; Jiang et al. 2018). It also indicates that bank managers tend to be more spiritual and socially supportive during crises. Therefore, we accept our hypothesis H3.

5 Additional and sensitivity analysis

We conduct additional analysis to examine the robustness of our inferences for the positive relationship between religiosity and disclosure quality. We use the three dimensions of religiosity separately as alternative measures of religiosity (Aggregate-REL), namely RAS, RI and RP. Table 5 shows that all three dimensions have a positive and significant association with VD_Q at 1% levels in both models. In addition, Big-4 and IA_C are positive and statistically significant at 1% and 5%, respectively. These findings align with those reported in Table 4, suggesting that religiosity positively impacts VD_Q regardless of the measurement approach.

To address the concern that the main measurement of VD_Q may have a skewed distribution, we conduct a sensitivity test to investigate whether our main findings are robust when utilising a different measure of disclosure quality. Consequently, we use the three dimensions of VD_Q separately as alternative measures of disclosure quality, namely, (1) ST_RQ, which represents the level of revealed information by the banks, and (2) spread which exemplifies the coverage and dispersion of the disclosed information, and (3) Usefulness of information based on the qualitative characteristics of IFRS. Table 6 reports that religiosity is positively and significantly associated with both spread and Usefulness dimensions at 1%. Nevertheless, both models show that religiosity has less influence on disclosure levels than the other dimensions at 10% and 5%, respectively. These outcomes are in line with the main findings in Table 4.

6 Substitutional sampling and endogeneity model

In this section, we use the substitution sample constructed to achieve the confidence that our main findings do signify the influence of religiosity on VD_Q. Consequently, we split the sample into several sub-sets and re-estimate all models. We identify the sub-setsFootnote 11 based on banks with relatively poor incentives to provide more information voluntarily. Zang (2011) argues that banks with high leverage, low profitability, low growth, low liquidity, and small size are less likely to disclose more information voluntarily and more frequently involved in unethical practices to avoid losses. Also, we have taken into account the impact of the financial crisis on our analysis and controlled it by dividing the sample into "before and after the crisis". Table 7 (Panel A and B) illustrates that the outcomes are similar to those presented in Table 4 and confirms that religiosity is positively and significantly correlated to VD_Q. In addition, the F-test of coefficient equality is adopted to ensure the reliability of the outcomes and compare the coefficients of the main variable of the three dimensions (AggregateREL) in the high versus low sub-samples. The F-test (untabulated) confirms the presented outcomes in Table 7. These findings are in line with the suggestion that religiosity has a significant impact on disclosure quality even within banks that struggle to maintain overall stability with relatively inferior capital, poor profitability and higher equity cost.

Beyond the aforementioned analyses, 2SLS regression is conducted to control for endogeneity and reassess the main results. Previous studies (e.g., Andreou et al. 2017b, a; Rezaee and Tuo 2019; Salem et al. 2020) suggested that managerial decisions influence corporate disclosure, which may lead to endogeneity issues. In addition, executives' characteristics such as gender, over-confidence, tenure and background could have an impact on corporate disclosure, organisational policies, tax avoidance, earnings management and bad news hoarding (Andreou et al. 2017b, a; Bamber et al. 2010; Baik et al. 2018, 2011; Bertrand and Schoar 2003). Durbin-WuHausman is utilised because there may be an endogeneity concern between the study variables. Although the finding of Durbin-WuHausman is insignificant (0.6908), we have taken into account several variables and techniques to mitigate any potential endogeneity (Wintoki et al. 2012). Following Liu and Zhou (2020), firstly, executives-gender is used as a proxy to control for managerial effects. Secondly, the lead-lag approach with the lagged values for all control variables is employed (Dhaliwal et al. 2011). Finally, we used regional variations of levels of social trust to construct the instrumental variable. Following McCleary and Barro (2003) we adopt religiosity to deal with any potential econometric problem in a cross-sectional framework. Consequently, the lag value of Aggregate-REL is treated as an endogenous variable and utilised in an instrumental variable estimation (lag- Aggregate-REL) (Chantziaras et al. 2020; Dhaliwal et al. 2011). We used F-statistic to ensure that our selected instrument is sufficiently strong. The F-statistic test illustrates that F (2, 10,129) = 11.63 which implies that the 2SLS estimator is valid. The result reported in Table 8 supports the main results reported earlier in Table 4. This outcome confirms the robustness of the key findings and is not impacted by the potential existence of endogeneity problems.

7 Conclusion

Our paper explores the impact of religiosity on voluntary disclosure quality. It employs a sample of 1,484 bank-year observations from 12 countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region over 14 years period (from 2006 to 2019). The empirical findings confirm the importance of religion in enhancing the quality of disclosed information in financial institutions. Our result indicates that religiosity is positively and significantly correlated with VD_Q after controlling for country and bank characteristics. In addition, we also report that the influence of religiosity on VD_Q is more pronounced among banks operating in countries with poor legal protection and weak control of corruption. Furthermore, we document that religion positively impacted VD_Q during the financial crisis period (2007–2009). We employed several sensitivity tests and additional analysis to test the robustness of our findings. The results of these tests indicate that religiosity enhances managerial decision-making, which improves the quality of disclosed information and reduces the risk of bank failure.

Our findings significantly contribute to the disclosure quality literature in the following ways. Firstly, our study bridges the gap in the prior study by Salem et al. (2021) and provides evidence that informal institution (religion) influences the disclosure quality (managerial decision) of banks in developing economies. Our result contributes to previous studies on how informal institutions influence organisational outcomes (North 1994). Secondly, this study has extended the ongoing debate on the role of religiosity in corporate disclosure practice. Particularly, we show that the interaction between the formal institution and religiosity positively impacts firms' disclosure quality. Our study also contributes to the debate on the importance of religiosity during the financial crisis. Our contribution is important to bank managers and policymakers since it helps them understand factors influencing the quality of disclosure in MENA regions.

These contributions have significant implications for policymakers to develop an effective regulatory framework that enhances disclosure quality in emerging economies. Our results have implications for investors since it helps investors to consider investments, especially in countries with strong religiosity but poor formal institutions. Also, we provide useful insights into the determinants of VD_Q in banks operating in the MENA region. Our findings have implications for societies. For instance, the positive impact of the interaction term between religiosity and crisis on VD_Q signifies that bank managers tend to be more spiritual and socially supportive during crises. This outcome is in line with the notion that religion provides emotional support and consistency in managerial decision-making during crisis periods.

The following limitations are attributed to our research design and may create an opportunity for further research. First, our measurement of religiosity considered only three dimensions and is taken as a country-level aggregated value. Therefore, it is difficult to generalise our results to those banks operating in developed economies. Further research could consider measuring religiosity across decision-makers within banks and the influence of managerial characteristics. The dataset excludes Islamic banks as they are regulated differently than their competitors. Further studies could consider Islamic banks to enrich our understanding of the subject. Moreover, our study focuses mainly on VD_Q in the banking sector. Further research can dig deeper into the impact of religiosity on "regulated" disclosure quality in different sectors. In addition, this study is limited to banks that are operating in Islamic countries within the MENA region, which may influence the generalisation of our findings. Therefore, further research is needed to consider more religiously diverse countries, including the U.S, Canada, the UK, France, and Singapore.

Notes

For example, IAS 38 requires listed firms to disclose a considerable amount and variety of important R&D information. However, it gives relevant high discretion in relation to the content of Corporate Social Responsibility reporting.

These countries include; Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt, Morocco, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Tunisia, Bahrain, Israel, Jordan and Iran.

RP = The percentage of respondents says that they are religious person "based on WVS".

RI = is the percentage of respondents that indicates religion is important to them "based on WVS".

RAS = is the percentage of respondents says that they attend religious services "based on WVS".

We follow recent literature (Menicucci, 2013; Elamer et al. 2020a, b; Sarhan and Ntim, 2018) to capture the information disclosed by conventional banks. For example, we employed content analysis and constructed a comprehensive checklist that covers items relevant to MENA banks. Following Salem et al. (2020) number of words was adjusted by bank size to capture the quantity dimension. Further information can be found in Salem et al. 2020

A detailed explanation about the measurement of each dimension can be found at “Salem, R.I.A., Ezeani, E., Gerged, A.M., Usman, M. and Alqatamin, R.M., (2020). Does the quality of voluntary disclosure constrain earnings management in emerging economies? Evidence from Middle Eastern and North African Banks. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management”.

Our sample consists of banks operating in countries experiencing political issues, namely; Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, Syria and Iraq.

Appendix III shows the measurement and definitions of all study variables used in the model.

The data of legal rights index is achieved from the Doing Business Project. More information could be found at http://www.doingbusiness.org/

The median value is used as a cut-off point to create 7 subsets.

References

Abdelsalam, O., Chantziaras, A., Ibrahim, M. and Omoteso, K., (2021). The impact of religiosity on earnings quality: International evidence from the banking sector. The British Accounting Review, p.100957.

Adhikari BK, Agrawal A (2016) Does local religiosity matter for bank risk-taking? J Corp Finan 38:272–293

Ahmad-Zaluki NA, Campbell K, Goodacre A (2011) Earnings management in Malaysian IPOs: the East Asian crisis, ownership control, and post-IPO performance. Int J Account 46(2):111–137

Alhazaimeh A, Palaniappan R, Almsafir M (2014) The impact of corporate governance and ownership structure on voluntary disclosure in annual reports among listed Jordanian companies. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 129:341–348

Alotaibi KO, Hussainey K (2016) Quantity versus quality: The value relevance of CSR disclosure of Saudi companies. Corp Ownersh Control 13(2):167–179

Andreou PC, Karasamani I, Louca C, Ehrlich D (2017a) The impact of managerial ability on crisis-period corporate investment. J Bus Res 79:107–122

Andreou PC, Louca C, Petrou AP (2017b) CEO age and stock price crash risk. Rev Finance 21(3):1287–1325

Anginer D, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Mare DS (2018) Bank capital, institutional environment and systemic stability. J Financ Stab 37:97–106

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297

Asyraf Wajdi D (2008). Understanding the objectives of Islamic banking: a survey of stakeholders’ perspectives. Int J Islam Middle East Finance Manag 1(2):132–148

Ba S, Lisic LL, Liu Q, Stallaert J (2013) Stock market reaction to green vehicle innovation. Prod Oper Manag 22(4):976–990

Baik B, Brockman PA, Farber DB, Lee S (2018) Managerial ability and the quality of firms’ information environment. J Acc Audit Financ 33(4):506–527

Baik BOK, Farber DB, Lee SAM (2011) CEO ability and management earnings forecasts. Contemp Account Res 28(5):1645–1668

Balasubramanyan L, Zaman S, Thomson JB (2014) Are banks forward-looking in their loan loss provisioning? Evidence from the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS)

Bamber LS, Jiang J, Wang IY (2010) What’s my style? The influence of top managers on voluntary corporate financial disclosure. Account Rev 85(4):1131–1162

Barnea A, Rubin A (2010) Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. J Bus Ethics 97(1):71–86

Beretta S, Bozzolan S (2008) Quality versus quantity: the case of forward-looking disclosure. J Acc Audit Financ 23(3):333–376

Bertrand M, Schoar A (2003) Managing with style: the effect of managers on firm policies. Q J Econ 118(4):1169–1208

Bewley K, Li Y (2000) Disclosure of environmental information by Canadian manufacturing companies: a voluntary disclosure perspective. In: Advances in environmental accounting and management. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87(1):115–143

Le Bon G (2002) The crowd: A study of the popular mind. Courier Corporation, North Chelmsford

Bornemann S, Kick T, Memmel C, Pfingsten A (2012) Are banks using hidden reserves to beat earnings benchmarks? Evidence from Germany. J Bank Finance 36(8):2403–2415

Brown S, Hillegeist SA (2007) How disclosure quality affects the level of information asymmetry. Rev Acc Stud 12(2):443–477

Bruton GD, Fried VH, Manigart S (2005) Institutional influences on the worldwide expansion of venture capital. Entrep Theory Pract 29(6):737–760

Callen JL, Fang X (2015) Religion and stock price crash risk. J Financ Quant Anal 50:169–195

Cantrell BW, Yust CG (2018) The relation between religiosity and private bank outcomes. J Bank Finance 91:86–105

Chantziaras A, Dedoulis E, Grougiou V, Leventis S (2020) The impact of religiosity and corruption on CSR reporting: The case of US banks. J Bus Res 109:362–374

Chen F, Chen X, Tan W, Zheng L (2020) Religiosity and cross-country differences in trade credit use. Account Finance 60:909–941

Chen H, Huang HH, Lobo GJ, Wang C (2016) Religiosity and the cost of debt. J Bank Finance 70:70–85

Cheng H, Huang D, Luo Y (2020) Corporate disclosure quality and institutional investors’ holdings during market downturns∗. J Corp Finan 60:101523

Chircop J, Fabrizi M, Ipino E, Parbonetti A (2017) Does branch religiosity influence bank risk-taking? J Bus Financ Acc 44(1–2):271–294

Chircop J, Johan S, Tarsalewska M (2020) Does religiosity influence venture capital investment decisions? J Corp Finan 62:101589

Cimini R (2015) How has the financial crisis affected earnings management? A European study. Appl Econ 47(3):302–317

Cohen DA, Dey A, Lys TZ (2008) Real and accrual-based earnings management in the pre-and post-Sarbanes-Oxley periods. Account Rev 83(3):757–787

Connelly BL, Certo ST, Ireland RD, Reutzel CR (2011) Signaling theory: a review and assessment. J Manag 37(1):39–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310388419

Conroy SJ, Emerson TL (2004) Business ethics and religion: religiosity as a predictor of ethical awareness among students. J Bus Ethics 50(4):383–396

Core JA (2001) A review of the empirical disclosure literature: discussion. J Account Econ 31(1–3):441–456

Cui J, Jo H, Velasquez MG (2015) The influence of Christian religiosity on managerial decisions concerning the environment. J Bus Ethics 132(1):203–231

Cui J, Jo H, Velasquez MG (2019) Christian religiosity and corporate community involvement. Bus Ethics Q 29(1):85–125

D’Amato A, Gallo A (2017) Does bank institutional setting affect board effectiveness? Evidence from cooperative and Joint-Stock banks. Corp Gov Int Rev 25(2):78–99

Davis JH, Schoorman FD, Donaldson L (1997) Toward a stewardship theory of management. Acad Manag Rev 22(1):20–47

Dhaliwal DS, Li OZ, Tsang A, Yang YG (2011) Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: the initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. Account Rev 86(1):59–100

Du X, Jian W, Du Y, Feng W, Zeng Q (2014b) Religion, the nature of ultimate owner, and corporate philanthropic giving: evidence from China. J Bus Ethics 123(2):235–256

Du X, Jian W, Zeng Q, Du Y (2014a) Corporate environmental responsibility in polluting industries: does religion matter? J Bus Ethics 124(3):485–507

Durkheim E (1965). The elementary forms of the religious life [1912], p 414.

Dye RA (1985) Disclosure of nonproprietary information. J Account Res 23(1):123–145. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490910

Dyreng SD, Hanlon M, Maydew EL (2010) The effects of executives on corporate tax avoidance. Account Rev 85(4):1163–1189

Dyreng SD, Mayew WJ, Williams CD (2012) Religious social norms and corporate financial reporting. J Bus Financ Acc 39(7–8):845–875

Díez-Esteban JM, Farinha JB, García-Gómez CD (2019) Are religion and culture relevant for corporate risk-taking? International evidence. BRQ Bus Res Qy 22(1):36–55

Elamer AA, Ntim CG, Abdou HA (2020b) Islamic governance, national governance, and bank risk management and disclosure in MENA countries. Bus Soc 59(5):914–955

Elamer AA, Ntim CG, Abdou HA, Pyke C (2020a) Sharia supervisory boards, governance structures and operational risk disclosures: Evidence from Islamic banks in MENA countries. Glob Financ J 46:100488

Elnahass M, Izzeldin M, Abdelsalam O (2014) Loan loss provisions, bank valuations and discretion: A comparative study between conventional and Islamic banks. J Econ Behav Organ 103:S160–S173

Epstein EM (2002) Religion and business–the critical role of religious traditions in management education. J Bus Ethics 38(1):91–96

Eriksson LMJ (2015) Social norms theory and development economics. In: World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (7450)

Ezeani E, Salem R, Kwabi F, Boutaine K, Komal B (2021) Board monitoring and capital structure dynamics: evidence from bank-based economies. Rev Quant Financ Account 58(2):473–498

Ezeani E, Kwabi F, Salem R, Usman M, Alqatamin RMH, Kostov P (2022) Corporate board and dynamics of capital structure: evidence from UK, France and Germany. Int J Finance Econom

Fields TD, Lys TZ, Vincent L (2001) Empirical research on accounting choice. J Account Econ 31(1–3):255–307

Filip A, Raffournier B (2012) The impact of the 2008–2009 financial crisis on earning management: the European evidence, Document de travail Chaire Financial Reporting ESSEC KPMG, Chaire Essec en Financial Reporting, Cergy Pontoise Cedex

Firebaugh G, Warner C, Massoglia M (2013) Fixed effects, random effects, and hybrid models for causal analysis. In: Handbook of causal analysis for social research, pp 113–132. Springer, Dordrecht

Francis B, Hasan I, Park JC, Wu Q (2015) Gender differences in financial reporting decision making: evidence from accounting conservatism. Contemp Account Res 32(3):1285–1318

Furfine CH (2001) Banks as monitors of other banks: evidence from the overnight federal funds market. J Bus 74(1):33–57

Geyer AL, Baumeister RF (2005). Religion, morality, and self-control: values, virtues, and vices

Ghazali NAM (2007) Ownership structure and corporate social responsibility disclosure: some Malaysian evidence. Corp Gov Int J Bus Soc

Ghosh S (2018) Governance reforms and performance of MENA banks: are disclosures effective? Glob Financ J 36:78–95

El Ghoul S, Guedhami O, Ni Y, Pittman J, Saadi S (2012) Does religion matter to equity pricing? J Bus Ethics 111(4):491–518

Di Giuli A, Kostovetsky L (2014) Are red or blue companies more likely to go green? Politics and corporate social responsibility. J Financ Econ 111(1):158–180

Glover RJ (1997) Relationships in moral reasoning and religion among members of conservative, moderate, and liberal religious groups. J Soc Psychol 137(2):247–254

Gokcekus O, Ekici T (2020) Religion, religiosity, and corruption. Rev Relig Res 62(4):563–581

Gorgan C, Gorgan V, Dumitru VF, Pitulice IC (2012) The evolution of the accounting practices during the recent economic crisis: empirical survey regarding the earnings management. Amfiteatru Econ J 14(32):550–562

Graham JR, Harvey CR, Rajgopal S (2005) The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. J Account Econ 40(1–3):3–73

Grougiou V, Dedoulis E, Leventis S (2016) Corporate social responsibility reporting and organizational stigma: The case of “Sin” industries. J Bus Res 69(2):905–914

Gujarati DN, Porter D (2009) Basic econometrics. Mc Graw-Hill International Edition

Halikiopoulou D, Vasilopoulou S (2016) 4 Political instability and the persistence of religion in Greece. In: Multireligious Society: Dealing with Religious Diversity in Theory and Practice, p. 63

Hambrick DC, Mason PA (1984) Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad Manag Rev 9(2):193–206

Hawtrey K, Johnson R (2010) On the atrophy of moral reasoning in the global financial crisis. J Relig Bus Ethics 1(2):4

Healy PM, Palepu KG (2001) Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: a review of the empirical disclosure literature. J Account Econ 31(1–3):405–440

Hedges LV, Vevea JL (1998) Fixed-and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods 3(4):486

Heilpern E, Haslam C, Andersson T (2009) When it comes to the crunch: what are the drivers of the US banking crisis? In: Accounting Forum, vol 33, no 2, pp 99–113. No longer published by Elsevier

Helmke G, Levitsky S (2004) Informal institutions and comparative politics: a research agenda. Perspect Polit 2(4):725–740

Hemingway C, Maclagan P (2004) Managers’ personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. J Bus Ethics 50(1):33–44

Hilary G, Hui KW (2009) Does religion matter in corporate decision-making in America? J Financ Econ 93(3):455–473

Horak S, Yang I (2018) A complementary perspective on business ethics in South Korea: Civil religion, common misconceptions, and overlooked social structures. Bus Ethics Eur Rev 27(1):1–14

IFRS (2010) Practice statement, MC, A framework for presentation. International Financial Reporting Standard, London

Issa A, Zaid MA, Hanaysha JR, Gull AA (2021) An examination of board diversity and corporate social responsibility disclosure: evidence from banking sector in the Arabian Gulf countries. Int J Account Inf Manag

Jaggi B, Low PY (2000) Impact of culture, market forces, and legal system on financial disclosures. Int J Account 35(4):495–519

Jiang F, John K, Li CW, Qian Y (2018) Earthly reward to the religious: religiosity and the costs of public and private debt. J Financ Quant Anal 53(5):2131–2160

Jizi MI, Salama A, Dixon R, Stratling R (2014) Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from the US banking sector. J Bus Ethics 125(4):601–615

Kanagaretnam K, Lobo GJ, Wang C (2015) Religiosity and earnings management: international evidence from the banking industry. J Bus Ethics 132(2):277–296

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Mastruzzi M (2011) The worldwide governance indicators: methodology and analytical issues1. Hague J Rule Law 3(2):220–246

Kennedy EJ, Lawton L (1998) Religiousness and business ethics. J Bus Ethics 17(2):163–175

Kim Y, Li H, Li S (2014) CEO equity incentives and audit fees. Contemp Account Res 32(3):608–638

Kohlberg L (1984) Essays on moral development/2 The psychology of moral development. Harper & Row, New York

Kothari SP (2001) Capital markets research in accounting. J Account Econ 31(1–3):105–231

Kouki A (2021) Does gender diversity moderate the link between CEO dominance and CSR engagement? A two-step system GMM analysis of UK FTSE 100 companies. J Sustain Finance Invest, pp 1–26

Kutcher EJ, Bragger JD, Rodriguez-Srednicki O, Masco JL (2010) The role of religiosity in stress, job attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior. J Bus Ethics 95(2):319–337

Leuz C, Verrecchia RE (2000) The economic consequences of increased disclosure. J Account Res 38:91–124

Leventis S, Dedoulis E, Abdelsalam O (2018) The impact of religiosity on audit pricing. J Bus Ethics 148(1):53–78

Levine R (2004) The corporate governance of banks: a concise discussion of concepts and evidence (Vol. 3404). World Bank Publications

Lim SJ, Lim SJ, White G, White G, Lee A, Lee A, Yuningsih Y (2017) A longitudinal study of voluntary disclosure quality in the annual reports of innovative firms. Account Res J 30(12):89–106

Lins KV, Servaes H, Tamayo A (2017) Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J Finance 72(4):1785–1824

Liu J, Zhou Y (2020) Do executives have fixed-effects on firm-level stock price crash and jump risk? Evidence from the CEOs and CFOs. Evidence From the CEOs and CFOs (June 11, 2020)

Longenecker JG, McKinney JA, Moore CW (2004) Religious intensity, evangelical Christianity, and business ethics: an empirical study. J Bus Ethics 55(4):371–384

Ma L, Wang X, Zhang C (2019) Does religion shape corporate cost behaviour? J Bus Ethics, pp 1–2.

Marquez-Illescas G, Zebedee AA, Zhou L (2019) Hear me write: does CEO narcissism affect disclosure? J Bus Ethics 159(2):401–417

Mazar N, Amir O, Ariely D (2008) The dishonesty of honest people: a theory of self-concept maintenance. J Mark Res 45(6):633–644

McCleary R, Barro R (2003) Religion and economic growth across countries, No. 3708464

McDougle L, Konrath S, Walk M, Handy F (2016) Religious and secular coping strategies and mortality risk among older adults. Soc Indic Res 125(2):677–694

McGuire ST, Omer TC, Sharp NY (2012) The impact of religion on financial reporting irregularities. Account Rev 87(2):645–673

McWilliams A, Siegel D (2001) Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective. Acad Manag Rev 26(1):117–127

Mehran H, Morrison AD, Shapiro JD (2012) Corporate governance and banks: what have we learned from the financial crisis? FRB of New York Staff Report, (502)

Melé D, Fontrodona J (2017) Christian ethics and spirituality in leading business organizations: editorial introduction. J Bus Ethics 145(4):671–679

Menicucci E (2013) The determinants of forward-looking information in management commentary: evidence from Italian listed companies. Int Bus Res 6(5):30

Myers SC, Majluf NS (1984) Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. J Financ Econ 13(2):187–221

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

North DC (1994) Economic performance through time. Am Econ Rev 84(3):359–368

Oh FD, Shin D (2020) Religion and corporate disclosure quality. Hitotsubashi J Econ 61(1):20–37

Orman WH (2019) Religiosity and financial crises in the United States. J Sci Study Relig 58(1):20–46

Parashar SP (2010) How did Islamic banks do during global financial crisis? Banks Bank Syst 5(4):54–62

Parboteeah KP, Hoegl M, Cullen JB (2008) Ethics and religion: an empirical test of a multidimensional model. J Bus Ethics 80(2):387–398

Patten DM, Zhao N (2014) Standalone CSR reporting by U.S. retail companies. Account Forum 38(2):132–144

Pearce JA (2013) Using social identity theory to predict managers’ emphases on ethical and legal values in judging business issues. J Bus Ethics 112(3):497–514

Piesse J, Strange R, Toonsi F (2012) Is there a distinctive MENA model of corporate governance? J Manage Gov 16(4):645–681

Pirinsky C, Wang Q (2006) Does corporate headquarters location matter for stock returns? J Financ 61(4):1991–2015

Platonova E, Asutay M, Dixon R, Mohammad S (2018) The impact of corporate social responsibility disclosure on financial performance: evidence from the GCC Islamic banking sector. J Bus Ethics 151(2):451–471

Qian X, Cao T, Cao C (2018) Institutional environment and bank loans: evidence from 25 developing countries. Corp Gov Int Rev 26(2):84–96

Rezaee Z, Tuo L (2019) Are the quantity and quality of sustainability disclosures associated with the innate and discretionary earnings quality? J Bus Ethics 155(3):763–786

Roodman D (2006) How to do xtabond2: an introduction to ‘difference’and ‘system. In GMM in STATA’, Center for Global Development Working Paper No. 103

Rosman R, Abd Wahab N, Zainol Z (2014) Efficiency of Islamic banks during the financial crisis: an analysis of Middle Eastern and Asian countries. Pac Basin Financ J 28:76–90

Rubin A (2008) Political views and corporate decision-making: the case of corporate social responsibility. Financ Rev 43(3):337–360

Sahyoun N, Magnan M (2020) The association between voluntary disclosure in audit committee reports and banks' earnings management. Manag Audit J

Salem R, Usman M, Ezeani E (2021) Loan loss provisions and audit quality: evidence from MENA Islamic and conventional banks. Q Rev Econ Finance 79:345–359

Salem RIA, Ezeani E, Gerged AM, Usman M, Alqatamin RM (2020). Does the quality of voluntary disclosure constrain earnings management in emerging economies? Evidence from Middle Eastern and North African Banks. Int J Account Inf Manage.

Sapp GL, Gladding ST (1989) Correlates of religious orientation, religiosity, and moral judgment. Counseling and Values

Sarhan AA, Ntim CG (2018) Firm-and country-level antecedents of corporate governance compliance and disclosure in MENA countries. Manag Audit J

Schipper K (1989) Earnings management. Account Horiz 3(4):91

Scholtens B (2009) Corporate social responsibility in the international banking industry. J Bus Ethics 86(2):159–175

Sherwood H (2018) Religion: Why faith is becoming more and more popular. Guardian 27:8

Shroff N, Sun AX, White HD, Zhang W (2013) Voluntary disclosure and information asymmetry: evidence from the 2005 securities offering reform. J Account Res 51(5):1299–1345

Sunstein CR (1996) Social norms and social roles. Columbia Law Rev 96(4):903–968

Swaen V, Chumpitaz RC (2008) Impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust. Rech Et Appl En Market (english Edition) 23(4):7–34

Tonoyan V, Strohmeyer R, Habib M, Perlitz M (2010) Corruption and entrepreneurship: How formal and informal institutions shape small firm behavior in transition and mature market economies. Entrep Theory Pract 34(5):803–832

Türegün N (2020) Does financial crisis impact earnings management? Evidence from Turkey. J Corp Account Finance 31(1):64–71

Usman M, Ezeani E, Salem RIA, Song X (2022) The impact of audit characteristics, audit fees on classification shifting: evidence from Germany. Int J Account Inf Manag 30:408–426

Vitell SJ (2009) The role of religiosity in business and consumer ethics: a review of the literature. J Bus Ethics 90:155–167

Walker A, Smither J, DeBode J (2012) The effects of religiosity on ethical judgments. J Bus Ethics 106(4):437–452

Wang Y, Campbell M (2012) Corporate governance, earnings management, and IFRS: empirical evidence from Chinese domestically listed companies. Adv Account 28(1):189–192

Weaver GR, Agle BR (2002) Religiosity and ethical behavior in organizations: a symbolic interactionist perspective. Acad Manag Rev 27:77–97

Wintoki MB, Linck JS, Netter JM (2012) Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. J Financ Econ 105(3):581–606

Xie B, Davidson WN III, DaDalt PJ (2003) Earnings management and corporate governance: the role of the board and the audit committee. J Corp Finan 9(3):295–316

Young S, Thyil V (2014) Corporate social responsibility and corporate governance: role of context in international settings. J Bus Ethics 122(1):1–24