Abstract

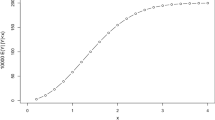

There are now a large and rapidly growing number of studies that test the constancy of stock return anomalies. In this study, we produce new and convincing evidence that the standard constancy test is heavily influenced by selection bias. Backed by a carefully designed Monte Carlo simulation, we show that selection bias predisposes the standard constancy test to reject the null by a factor of five to 12 times more than normally expected. Failure to recognize this bias can result in publication of the type of pseudo discoveries that Harvey (J Finance 72(4):1399–1440, 2017) warns about in his Presidential Address to the American Finance Association. We then describe the Quandt/Andrews test, a correct and unbiased test for anomalies and changes in anomalies, and apply it to test the constancy of 15 well-known stock return anomalies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See also Harvey et al. (2016) and Harvey’s Keynote Address at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the Financial Management Association entitled “Fake Research” for more on statistical bias in financial research.

Greenstone and Oyer (2000) also raise this fundamental and important concern in the context of testing for industry-specific calendar anomalies.

Ten of the 15 anomalies we will later test for constancy are significant at the one percent level.

It is not possible to test all subperiods only all possible subperiods. As a difference in means test, the Chow F-test requires two subperiods in which to calculate and then compare the means. We follow the standard approach, which is to start by testing a subperiod containing the first 15 percent of total observations against a subperiod containing the last 85 percent of total observations. Then continue by moving forward one month and re-doing the test. The final test is between the first 85 percent of total observations against the last 15 percent of total observations. The sequence of Chow F-statistics is thus only calculated between the first 15 percent and the last 15 percent of total monthly return observations. The value of 15 percent is known as the trimming parameter.

The current Web address is http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html.

The supF-statistics in Figs. 2 and 3 and in Table 2 are corrected for heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation whereas the subperiods in Table 3 correspond to the month of the uncorrected supF-statistics. This is exactly the correct approach though because the exogenous subperiods are defined by minimum total RSS and this is not affected by heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation.

References

Andrews DWK (1991) Heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix estimation. Econometrica 59(3):817–858

Andrews DWK (1993) Tests for parameter instability and structural change with unknown change point. Econometrica 61(4):821–856

Andrews DWK (2003) Tests for parameter instability and structural change with unknown change point: a corrigendum. Econometrica 71(1):395–397

Andrews DWK, Ploberger W (1994) Optimal tests when a nuisance parameter is present only under the alternative. Econometrica 62(6):1383–1414

Ang A, Hodrick RJ, Xing Y, Zhang X (2006) The cross-section of volatility and expected returns. J Finance 61(1):259–299

Banz RW (1981) The relationship between return and market value of common stocks. J Financ Econ 9:3–18

Basu S (1977) Investment performance of common stocks in relation to their price-earnings ratios: a test of the efficient market hypothesis. J Finance 32(3):663–682

Bebchuk LA, Cohen A, Wang CC (2013) Learning and the disappearing association between governance and returns. J Financ Econ 108:323–348

Ben-David D, Papell DH (1998) Slowdowns and meltdowns: Postwar growth evidence from 74 countries. Rev Econ Stat 80(4):561–571

Bhattacharya D, Li WH, Sonaer G (2017) Has momentum lost its momentum? Rev Quant Financ Acc 48:191–218

Chordia T, Subrahmanyam A, Tong Q (2014) Have capital market anomalies attenuated in the recent era of high liquidity and trading activity? J Acc Econ 58:41–58

Cooper MJ, Gulen H, Schill MJ (2008) Asset growth and the cross-section of stock returns. J Finance 63(4):1609–1651

Darrat AF, Li B, Chung R (2013) The other month effect: a re-examination of the “other January” anomaly. Rev Pac Basin Financ Mark Polic 16(2):1–23

De Bondt WFM, Thaler R (1985) Does the stock market overreact? J Finance 40(3):793–805

Fama EF, French KR (1992) The cross-section of expected stock returns. J Finance 47(2):427–465

Fama EF, French KR (2016) Dissecting anomalies with a five-factor model. Rev Financ Stud 29(1):69–103

Fama EF, MacBeth JD (1973) Risk, return, and equilibrium: empirical tests. J Polit Econ 81(3):607–636

French KR (1980) Stock returns and the weekend effect. J Financ Econ 8:55–69

Gibbons MR, Hess P (1981) Day of the week effects and asset returns. J Bus 54(4):579–596

Greenstone M, Oyer P (2000) Are there sectoral anomalies too? The pitfalls of unreported multiple hypothesis testing and a simple solution. Rev Quant Financ Acc 15:37–55

Hansen BE (1997) Approximate asymptotic P values for structural-change tests. J Bus Econ Stat 15(1):60–67

Hansen BE (2001) The new econometrics of structural change: Dating breaks in U.S. labor productivity. J Econ Perspect 15(4):117–128

Harvey CR (2017) Presidential address: the scientific outlook in financial economics. J Finance 72(4):1399–1440

Harvey CR, Liu Y, Zhu H (2016)... and the cross-section of expected returns. Rev Financ Stud 29(1):5–68

Haugen RA, Heins AJ (1975) Risk and the rate of return on financial assets: some old wine in new bottles. J Financ Quant Anal 10(5):775–784

Holland PW (1986) Statistics and causal inference. J Am Stat Assoc 81(396):945–960

Jaffe J, Keim DB, Westerfield R (1989) Earnings yields, market values, and stock returns. J Finance 44(1):135–148

Jegadeesh N (1990) Evidence of predictable behavior of security returns. J Finance 45(3):881–898

Jegadeesh N, Titman S (1993) Returns to buying winners and selling losers: implications for stock market efficiency. J Finance 48(1):65–91

Jegadeesh N, Titman S (2001) Profitability of momentum strategies: an evaluation of alternative explanations. J Finance 56(2):699–720

Lakonishok J, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1994) Contrarian investment, extrapolation, and risk. J Finance 49(5):1541–1578

Linnainmaa JT, Roberts MR (2018) The history of the cross section of stock returns. Rev Financ Stud 31(7):2606–2649

McConnell MM, Perez-Quiros G (2000) Output fluctuations in the United States: what has changed since the early 1980’s? Am Econ Rev 90(5):1464–1476

McLean RD, Pontiff J (2016) Does academic research destroy stock return predictability? J Finance 71(1):5–32

Naranjo A, Nimalendran M, Ryngaert M (1998) Stock returns, dividend yields, and taxes. J Finance 53(6):2029–2057

Newey WK, West KD (1987) A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica 55(3):703–708

Novy-Marx R (2013) The other side of value: the gross profitability premium. J Financ Econ 108:1–28

Pontiff J, Woodgate A (2008) Share issuance and cross-sectional returns. J Finance 63(2):921–945

Quandt RE (1958) The estimation of the parameters of a linear regression system obeying two separate regimes. J Am Stat Assoc 53(284):873–880

Quandt RE (1960) Tests of the hypothesis that a linear regression system obeys two separate regimes. J Am Stat Assoc 55(290):324–330

Robins RP, Smith GP (2016) No more weekend effect. Crit Finance Rev 5:417–424

Schwert GW (2003) Anomalies and market efficiency. In: Constantinides G, Harris M, Stulz R (eds) Handbook of the economics of finance, chapter 15. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 937–972

Sloan RG (1996) Do stock prices fully reflect information in accruals and cash flows about future earnings? Acc Rev 71(3):289–315

Stock JH, Watson MW (1996) Evidence on structural instability in macroeconomic time series relations. J Bus Econ Stat 14(1):11–30

Zeileis A, Leisch F, Hornik K, Kleiber C (2002) strucchange: an R package for testing for structural change in linear regression models. J Stat Softw 7(2):1–38

Zeileis A, Kleiber C, Krämer W, Hornik K (2003) Testing and dating of structural changes in practice. Comput Stat Data Anal 44:109–123

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Richard Hahn, Cheng-Few Lee (Editor), Ivo Welch, an anonymous referee, and the participants at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Southern Finance Association for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Robins, R.P., Smith, G.P. Selection bias and pseudo discoveries on the constancy of stock return anomalies. Rev Quant Finan Acc 55, 1407–1426 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-020-00878-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-020-00878-w