Abstract

The main purpose of this paper is to examine the wealth effect of stock repurchase announcements using a sample of 11,862 repurchase programs announced during 1994–2007. The results of several recent industry surveys indicate that managerial motivations for repurchasing shares may have changed in recent years. To better understand the reasons for repurchasing shares we classify our sample in various ways—by year, by the method used for repurchasing shares, and by the stated purpose of the program. We find that the median size of firms repurchasing shares has increased dramatically recently, and concomitantly, the announcement returns have declined. Signaling undervaluation of share prices appears to become less important than previously assumed. While smaller firms signal undervaluation using open market repurchases, tender offers are chosen to enhance shareholder values by other means.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, Business Wire reported on August 28, 2006 that “Amazon.com, Inc. (the “Company”) announced today that its Board of Directors authorized the Company to repurchase up to $500 million of the Company's common stock within the next 24 months, through one or more open market transactions, privately negotiated transactions, transactions structured through investment banking institutions or a combination of the foregoing. The Company may do so if it believes its shares are undervalued.”

Business Wire, December 18 2006.

Business Wire, June 16 2006.

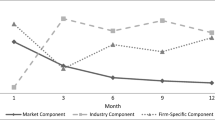

All our conclusions remain the same when we use the Fama–French three-factor model instead of the market model.

According to Cowan and Sergeant (1996), the Patell test standardizes the event-date prediction error for each stock by its standard deviation. The individual prediction errors are assumed to be cross-sectionally independent and distributed normally, so each standardized prediction error has a Student t distribution. By the Central Limit Theorem, the distribution of the sample average standardized prediction error is normal. The resulting test statistic is

\( {\raise0.7ex\hbox{${Z = \sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^{N} {{\text{SR}}_{\text{jE}} } }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{Z = \sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^{N} {{\text{SR}}_{\text{jE}} } } {\sqrt {\sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^{N} {{\frac{{{\text{T}}_{j} - 2}}{{{\text{T}}_{j} - 4}}}} } }}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${\sqrt {\sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^{N} {{\frac{{{\text{T}}_{j} - 2}}{{{\text{T}}_{j} - 4}}}} } }$}}, \)where SRjE is a stock j’s estimated standard deviation of abnormal return during the estimation period; T is number of trading days in stock j’s estimation period, equal to 255 if there is no missing return.

The rank test procedure treats the 255-day estimation period and the event day as a single 256-day time series, and assigns a rank to each daily return for each firm. K jt represent the rank of abnormal return AR jt in the time series of 256 daily abnormal returns of stock j. Rank one signifies the smallest abnormal return. We adjust for missing returns by dividing each rank by the number of non-missing returns in each firm’s time series plus one:

U jt = K jt /(M j + 1),

where M j is the number of non-missing abnormal returns for stock j. The rank test statistic is

\( {\raise0.7ex\hbox{${Z = {\frac{1}{\sqrt N }}\sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^{N} {\left( {U_{jt} - 0.5} \right)} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{Z = {\frac{1}{\sqrt N }}\sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^{N} {\left( {U_{jt} - 0.5} \right)} } {S_{u} }}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${S_{u} }$}}, \)where the standard deviation Su is

\( S_{u} = \sqrt {\frac{1}{256}} \sum\nolimits_{t = - 255}^{0} {\left[ {\sqrt {{\frac{1}{{\sqrt {N_{t} } }}}\sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^{{N_{t} }} {\left( {U_{it} - 0.5} \right)} } } \right]} , \)

where N t is nonmissing returns across the stocks in the sample on day t of the combined estimation and event period.

For the pre-announcement returns, market model parameters are estimated by regressing each firm’s daily return on the CRSP value-weighted index return over 255 trading days, beginning on day −406 and ending 151 trading days before the announcement date.

We also provide cross-sectional regression evidence later (in Table 9) that announcement-period CARs are significantly negatively correlated with pre-announcement CARs before 2003. The correlation is positive and statistically insignificant between 2003 and 2007. A significantly negative regression coefficient suggests that repurchase announcements signal undervalued share prices. The regression evidence presented in Table 9 strengthens our argument that recent repurchase announcements by relatively bigger firms are made for reasons that may not have much to do with signaling undervalued shares.

Previous studies report abnormal returns of 3–5% for open market repurchases and 8–15% for fixed-price and Dutch-auction tender offers.

Dutch-auction tender offers are also less expensive for the repurchasing firms because the purchase (winning) price in a Dutch-auction is likely to be lower than the purchase price of a fixed-price offer.

Open market/negotiated repurchases are considered as open market repurchases.

The GLMMOD procedure constructs the design matrix for a general linear model. When we use SAS's REG procedure to fit a model with a classification variable like the repurchase methods and the stated purpose of repurchases, we first need to compute the indicator (dummy) variables. The GLMMOD procedure creates the indicator variables automatically and uses them as input to other SAS procedures.

According the SAS manual, if a CLASS variable has m levels, GLMMOD will generate m variables in the design matrix. This means that the model produced by GLMMOD is overparameterized. There are more columns for these effects than there are degrees of freedom for them. Therefore, we need to drop at least one column for each class variable when we fit the model. Among the four repurchase methods, we drop negotiated repurchases. Among the six stated purposes of repurchases, we drop repurchases that are coded as “General Corporate Purpose.”

References

Bagwell L (1991) Share repurchase and takeover deterrence. Rand J Econ 22:72–88

Bagwell L, Shoven J (1989) Cash distributions to shareholders. J Econ Perspect 3:129–140

Baker HK, Powell GE, Veit ET (2003) Why companies use open-market repurchases: a managerial perspective. Q Rev Econ Finance 43:483–504

Bozanic Z (2010) Managerial motivation and timing of open market share repurchases. Rev Quant Financ Acc 34:517–531

Bradley M, Wakeman L (1983) The wealth effects of targeted share repurchases. J Financ Econ 11:301–328

Brav A, Graham J, Harvey C, Michaely R (2005) Payout policy in the 21st century. J Financ Econ 77:483–527

Chan K, Ikenberry D, Lee I (2004) Economic sources of gain in stock repurchases. J Financ Quant Anal 39:461–479

Comment R, Jarrell GA (1991) The relative signaling power of Dutch-auction and fixed-price self-tender offers and open-market share purchases. J Finance 46:1243–1271

Cowan AR, Sergeant AMA (1996) Trading frequency and event study test specification. J Bank Finance 20:1731–1757

D’Mello R, Schroff R (2000) Equity undervaluation and decisions related to repurchase tender offers: an empirical investigation. J Finance 55:2399–2424

Dann LY (1981) Common stock repurchases: an analysis of returns to bondholders and stockholders. J Financ Econ 9:113–138

Dann L, De Angelo H (1983) Standstill agreements privately negotiated stock repurchases, and the market for corporate control. J Financ Econ 11:275–300

Dittmar A (2000) Why do firms repurchase stock? J Bus 73:331–355

Dittmar A, Dittmar R (2008) The timing of financing decisions: an examination of the correlation in financing waves. J Financ Econ 90:1–58

Fenn G, Liang N (2001) Corporate payout policy and managerial stock incentives. J Financ Econ 60:1–44

Graham JR, Harvey CR (2001) The theory and practice of corporate finance: evidence from the field. J Financ Econ 60:187–243

Grullon G, Michaely R (2002) Dividends, share repurchases, and the substitution hypothesis. J Finance 57:1649–1684

Grullon G, Michaely R (2004) Information content of share repurchase program. J Finance 59:651–680

Hribara P, Jenkins NT, Johnson WB (2006) Stock repurchases as an earnings management device. J Account Econ 41:3–27

Ikenberry D, Lakonishok J, Vermaelen T (1995) Market underreaction to open market share repurchases. J Financ Econ 39:181–208

Ikenberry D, Lakonishok J, Vermaelen T (2000) Stock repurchases in Canada: performance and strategic trading. J Finance 55:2373–2397

Jagannathan M, Stephens C (2003) Motives for multiple open market repurchase programs. Financ Manag 71–91

Kahle K (2002) When a buyback isn’t a buyback: open market repurchases and employee options. J Financ Econ 63:235–261

Klein A, Rosenfeld J (1988) The impact of targeted share repurchases on the wealth of non-participating shareholders. J Financ Res 11:89–97

Lakonishok J, Vermaelen T (1990) Anomalous price behavior around repurchase tender offers. J Finance 45:455–477

Lambert RA, Lanen WN, Larcker DF (1989) Executive stock option plans and corporate dividend policy. J Financ Quant Anal 24:409–425

Louis H, White H (2007) Do managers intentionally use repurchase tender offers to signal private information? Evidence from firm financial reporting behavior. J Financ Econ 85:205–233

McNally WJ (1999) Open market stock repurchase signaling. Financ Manag 28:55–67

Nohel T, Tarhan V (1998) Share repurchase and firm performance: new evidence of the agency costs of free cash flow. J Financ Econ 49:187–222

Oswald D, Young S (2004) What role taxes and regulation? A second look at open market share buyback activity in the UK. J Bus Finance Account 31:257–292

Peyer UC, Vermaelen T (2005) The many facets of privately negotiated stock repurchases. J Financ Econ 75:361–395

Ramsay I, Lamba AS (2000) Share buy-backs: an empirical investigation. SSRN Working Paper Series. Rochester

Rau P, Vermaelen T (2002) Regulation, taxes and share repurchases in the United Kingdom. J Bus 75:245–282

Skinner D (2008) The evolving relation between earnings, dividends, and stock repurchases. J Financ Econ 87:582–609

Stephens CP, Weisbach MS (1998) Actual share reacquisition in open-market repurchase programs. J Finance 53:313–333

Tsetsekos GP, Kaufman DJ, Gitman LJ (1991) A survey of stock repurchase motivations and practices of major U.S. corporations. J Appl Bus Res 7:15–20

Vermaelen T (1981) Common stock repurchases and market signaling. J Financ Econ 9:139–183

Wansley JW, Lane WR, Sarkar S (1989) Managements’ view on share repurchase and tender offer premiums. Financ Manag 18:97–110

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yook, K.C., Gangopadhyay, P. A comprehensive examination of the wealth effects of recent stock repurchase announcements. Rev Quant Finan Acc 37, 509–529 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-010-0215-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-010-0215-y