Abstract

The 2023 Merger Guidelines make some notable improvements over the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines. They give greater emphasis to the idea that predicting the competitive effects of a proposed merger is inherently difficult and that to block a merger the government need only show a risk that the merger may substantially lessen competition – not that it will do so. They also give greater emphasis to dynamic competition and innovation – especially with regard to acquisitions of potential entrants – and they add useful material on multi-sided platforms. However, the treatment of market definition in the 2023 Merger Guidelines may weaken horizontal merger enforcement by demoting the role of the “hypothetical monopolist test,” which is used to define markets for the purpose of measuring market shares, and by removing extensive material from prior guidelines that explained why market shares measured in narrower markets tend to be more informative than market shares measured in broader markets. The 2023 Merger Guidelines lower the market concentration thresholds that trigger a presumption by the antitrust enforcement agencies that a merger may substantially lessen competition, but the enforcement data suggest that change will have little effect in practice. The 2023 Merger Guidelines also may lead to less effective deterrence of harmful mergers because they are not well targeted at the mergers that are most likely to substantially lessen competition. One cannot prioritize everything.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The 2023 Merger Guidelines represent the latest step in a process by which merger guidelines that are issued by the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) have evolved since the first merger guidelines were issued by the DOJ in 1968.

In this article, I focus on the changes in the 2023 Merger Guidelines (“2023 MGs”) compared with their immediate predecessor regarding horizontal mergers, the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines (“2010 HMGs”). I do not examine the changes with regard to vertical mergers compared with the 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines.

The 2010 HMGs were the triumph of the fox over the hedgehog, as explained by Shapiro (2010). The hedgehog knows one big thing: the structural presumption against mergers that substantially increase market concentration. But the fox knows many things: a collection of approaches and methods to assess whether a merger may substantially lessen competition. The fox examines a wide range of evidence to assess how a merger will most likely affect market outcomes, recognizing that markets in a modern economy differ immensely in how they operate. Thirteen years later, the fox is fully ascendent. The 2023 MGs identify even more ways in which the DOJ and the FTC (the “Agencies”) can find that a merger may substantially lessen competition.

This article asks whether the updated fox is too clever by half. In their zeal to deter and block more mergers, have the Agencies overreached and spread their attention too broadly, with the unintended effect of undermining the statutory goal of preventing mergers that may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly? One cannot prioritize everything.

In Sect. 2, I identify some notable improvements in the 2023 MGs that should help strengthen horizontal merger enforcement. The most significant improvement is their emphasis on whether a merger poses a meaningful risk of harming competition. Hopefully, this framing will help the courts better appreciate that merger analysis is inherently uncertain, and that the government need show only that a merger may substantially lessen competition –not that it will do so. The case law already makes this point clear, but some courts have been too demanding.

Section 3 discusses market definition in the 2023 MGs. Defining a relevant market is a necessary predicate for invoking the structural presumption, under which a merger that substantially increases market concentration is presumed to be illegal. The structural presumption is critical to effective merger enforcement – notwithstanding the triumph of the fox in the merger guidelines. The 2023 MGs clearly intend to strengthen merger enforcement, but I fear that they may have the opposite effect because of the way they treat market definition.Footnote 1

More specifically, the 2023 MGs take a big step backward by demoting the “hypothetical monopolist test” (HMT). Often, the government alleges a properly defined and relatively narrow relevant market based on the HMT, and the merging parties argue for a broader market in which their shares are misleadingly smaller. The HMT can thus be essential when the government seeks to establish the structural presumption.

I therefore find it puzzling and very worrisome that the 2023 MGs demote the HMT. This demotion may weaken merger enforcement by making it harder for the government to prevail in court when it should. This is both unfortunate and ironic, given that the Agencies are seeking to strengthen merger enforcement and given that the 2023 MGs appear to tighten merger enforcement by lowering the concentration thresholds that trigger the structural presumption. But appearances can be deceptive, because the concentration thresholds can be applied only after a relevant market is defined.

Section 4 turns specifically to the market concentration thresholds in the 2023 MGs. The Agencies state that they reverted to the thresholds that were used from 1982 to 2010 to trigger the structural presumption “based on experience and evidence developed since” 2010. However, they provide no indication of that experience or evidence. The evidence from merger retrospectives is not nearly precise enough for this purpose.Footnote 2 In addition, the 2023 MGs add a new threshold for mergers that lead to a firm with a market share greater than 30% and an increase in the HHI of more than 100. However, the Supreme Court case cited for this threshold involved an increase in the HHI of roughly 600. The 2023 MGs also eliminate “safe harbors” for mergers in unconcentrated markets and mergers that have little effect on market concentration, without explanation.

Section 4 also presents data indicating that lowering the HHI thresholds that trigger the structural presumption back to the levels that prevailed prior to 2010 is unlikely in practice to lead to stricter horizontal merger enforcement.

In Sect. 5, I explain why the 2023 MGs may not be effective at identifying and deterring harmful mergers. They are not well targeted and thus will impose additional costs and risks on mergers that are unlikely to lessen competition. The 2023 MGs do not include one of the goals that is explicitly identified in prior guidelines: “avoiding unnecessary interference with mergers that are either competitively beneficial or neutral.” (2010 HMGs, p. 1) The very broad sweep of the 2023 MGs also makes it more likely that the Agencies will expend resources investigating and litigating relatively benign or beneficial mergers, which will leave fewer resources to investigate and challenge the most harmful ones. Section 6 concludes.

2 Notable Improvements in the 2023 Merger Guidelines

The 2023 Merger Guidelines introduce a number of notable improvements over prior guidelines. These constructive additions are especially welcome given the deeply flawed Draft Merger Guidelines that were released to the public in July 2023.Footnote 3

2.1 “May” Means May

The 2023 MGs emphasize that merger analysis is about whether a merger may substantially lessen competition. The very first page of the 2010 HMGs made this point,Footnote 4 but some courts appear to have nonetheless required proof that a merger will substantially harm competition.

The 2023 MGs (pp. 1–2) stress that the statute uses the verb “may:”

“Accordingly, the Agencies do not attempt to predict the future or calculate precise effects of a merger with certainty. Rather, the Agencies examine the totality of the evidence available to assess the risk the merger presents.”

This welcome focus on the risk of harm to competition follows naturally if one recognizes that mergers can create public benefits as well as harms and takes a decision-theoretic approach to merger enforcement.Footnote 5 The focus on risk also is very much consistent with an important 2013 Supreme Court decision that ruled that settlements of patent litigation including an agreement not to compete can violate the antitrust laws if they “prevent the risk of competition.”Footnote 6

The 2023 MGs (pp. 35, 36) also explain that quantification of harm is not required and often impossible:

“When data is available, the Agencies recognize that the goal of economic modeling is not to create a perfect representation of reality, but rather to inform an assessment of the likely change in firm incentives resulting from a merger.”

“The Agencies use such models to give an indication of the scale and importance of competition, not to precisely predict outcomes.”

These statements accurately reflect how quantification is used in practice: as an indication of the harm that a merger may cause, not as a measure of actual harm such as when an economist estimates damages. Hopefully, these statements will help the courts appreciate the inherent limitations associated with the economic modelling of proposed mergers. They also should reduce the danger that a court will rule against the government simply because the government’s economic expert did not quantify the harm to customers caused by the merger.

2.2 Dynamic Competition and Innovation

The 2023 MGs give greater emphasis to dynamic competition and innovation than did prior merger guidelines. They build on the 2010 HMGs, which introduced a section on “Innovation and Product Variety.” In this respect, the 2023 MGs represent the next step in the ongoing evolution of horizontal merger guidelines, placing less emphasis on static measures such as market concentration and prices and more emphasis on technological change and innovation. The greater emphasis on dynamic competition is fitting given the critical role that is played by innovation in driving economic growth and improved standards of living.

Rose and Shapiro (2022) explain the basic challenge that one faces when evaluating a merger that involves dynamic competition:

“Protecting dynamic competition is inherently challenging. The fundamental problem is that incumbent firms often find it more profitable to acquire potential rivals than to compete against them. Therefore, the Agencies and the courts must be alert to the danger that merging firms will stymie effective merger enforcement by combining at a relatively early date, when the evidence a loss of dynamic competition is less clear, especially to those outside the industry.” (p. 8, footnote omitted)

They suggest a solution to this problem:

“Given the inevitable evidentiary challenges the Agencies face when they challenge mergers based on a loss of dynamic competition, we urge the Agencies to emphasize in the updated HMGs that they focus on the ability and incentive of the merged firms to invest and introduce competing products in the future.” (p. 8, footnote omitted)

The 2023 MGs adopt this basic “ability and incentive” approach. Guideline 4 states: “Mergers Can Violate the Law When They Eliminate a Potential Entrant in a Concentrated Market.” Here is the first step under Guideline 4 to evaluate a merger that may eliminate a potential entrant:

“Reasonable Probability of Entry. The Agencies’ starting point for assessment of a reasonable probability of entry is objective evidence regarding the firm’s available feasible means of entry, including its capabilities and incentives.” (p. 11)

This is a sound approach.Footnote 7 In particular, requiring that the firm in question has made specific plans to enter in the near future would undermine effective enforcement in this area – especially as firms would then refrain from writing down such plans if they were contemplating a merger.

Guideline 4 (p. 11) also offers useful guidance on how objective evidence can establish that entry is reasonably likely: “Relevant objective evidence can include, for example, evidence that the firm has sufficient size and resources to enter; evidence of any advantages that would make the firm well-situated to enter; evidence that the firm has successfully expanded into similarly situated markets in the past or already participates in adjacent or related markets; evidence that the firm has an incentive to enter; or evidence that industry participants recognize the company as a potential entrant.”

Unfortunately, Guideline 4 falters when it turns to subjective evidence: “Subjective evidence that the company considered organic entry as an alternative to merging generally suggests that, absent the merger, entry would be reasonably probable.” This statement should have been qualified. For example, if the company considered organic entry and rejected it due to its lack of key capabilities or because it would take much longer or be unlikely to succeed, the opposite inference would be more reasonable.

Here, as elsewhere, the 2023 MGs also leave themselves vulnerable by grounding their authority in case citations rather than persuasive economic reasoning. In particular, Guideline 4 makes the following statement: “A merger that eliminates a potential entrant into a concentrated market can substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.” (p. 10) If that proposition were presented purely as a matter of economics, it would be unassailable. But the 2023 MGs support this assertion with a citation to a 50-year-old decision by the Supreme Court upholding the District Court’s finding that the government had failed to establish that entry was reasonably likely to produce significant procompetitive effects.Footnote 8 Plus, once the guidelines start citing cases, which cases do they include and where do they stop? As a prominent example, the 2023 MGs do not tell us if the term “reasonable probability of entry” as used in the guidelines has the same meaning as in a 2023 case that the FTC lost that they do not cite.Footnote 9 This is not a small issue, especially given the overall “risk to competition” framework that is adopted by the 2023 MGs.

2.3 Multi-Sided Platforms

The 2023 MGs include a detailed discussion of how the Agencies analyze mergers that involve multi-sided platforms. Guideline 9 explains that “the Agencies Examine Competition Between Platforms, on a Platform, or to Displace a Platform.”

Multi-sided platforms are quite important in today’s economy, and the largest platforms account for a vast volume of commerce. Economic learning about these platforms has advanced greatly in recent years, but that learning is not yet reflected in the case law.Footnote 10 For all these reasons, the inclusion of Guideline 9 is most welcome. The discussion of Guideline 9 shows a deep understanding of how competition involving multi-sided platforms actually takes place.

But I do have a not-so-small quibble. The 2023 MGs should have recognized that a platform operator generally has an incentive to manage its platforms so as to enhance the platform’s overall value in competition with other platforms and that platform management typically involves trading off the interests of different “sides” on the platform.

For this reason, the antitrust priority should be to promote and protect competition between platforms, including competition to displace a platform. These are examples of what antitrust law and economics refer to in more conventional settings as “inter-brand” competition. Unfortunately, Guideline 9 does not sufficiently distinguish these forms of platform competition from competition on a platform, which is more akin to “intra-brand” competition in antitrust law and economics.

The key point is that a platform operator has an incentive to promote competition on its own platform if that greater competition will enhance the overall value of its platform. In some cases, this will involve the platform operator acquiring a complement to the platform, perhaps to speed up innovation by providing greater integration of the complement and the platform itself. The 2023 MGs appear to be unduly hostile to such acquisitions because they create what is called a “conflict of interest.”Footnote 11

2.4 Mergers of Competing Employers

The 2023 MGs explain how mergers between competing employers can harm competition in labor markets. This material, which appears as part of Guideline 10, is another welcome addition.Footnote 12 Here again, the 2023 MGs are the next step in an evolutionary process. One of the major innovations in the 2010 HMGs was a section entitled “Mergers of Competing Buyers.” That new section made the central point that a merger between competing buyers can lessen competition for suppliers even if it does not lessen competition for customers at all.

The 2023 MGs state: “Labor markets frequently have characteristics that can exacerbate the competitive effects of a merger between competing employers.” (p. 27) Adding material specifically about protecting workers provides political benefits to the Biden Administration.

The February 2024 FTC challenge to the merger between Kroger and Albertsons breaks new ground by defining a market for “union grocery labor.”Footnote 13 However, it is not clear just what these union labor markets add to the FTC’s case. For example, do they encompass geographies not covered by the relevant markets for supermarkets? This case and its aftermath bear watching.

It remains to be seen how many of their scarce resources the Agencies will or should devote to evaluating the effects of mergers in labor markets. Routinely asking merging parties about labor market issues does not appear to be efficient. Shapiro (2019, p. 88) made this point: “If the antitrust authorities seriously want to explore the possibility of challenging mergers on the basis of harm to competition in labor markets, developing a quick and efficient means of identifying mergers that involve a significant overlap in plausible labor markets would be a good first step.” The 2023 MGs do not provide such a screening method. I hope that the Agencies are developing one internally based on their accumulating experience examining the effects of mergers between competing employers. Only time will tell just how fruitful this part of the 2023 MGs will be.

3 Market Definition in the 2023 MGs: A Big Step Backward

The fox has prevailed, but the hedgehog’s one big idea – mergers that substantially increase concentration in a properly defined relevant market are presumed to be illegal – still occupies the top spot on the fox’s own list. The structural presumption – which goes back to the Supreme Court’s landmark 1963 decision in Philadelphia National BankFootnote 14– appears as Guideline 1.

Thus has the hedgehog exacted its revenge.

Guideline 1 may be only one of six “frameworks the Agencies use to identify that a merger raises prima facie concerns” (p. 2), but in practice the structural presumption dominates merger enforcement. Hovenkamp and Shapiro (2018) explain that the structural presumption has been central to horizontal merger enforcement for over 50 years. In every case where the Agencies challenge a merger between actual competitors, they define a relevant market and invoke the structural presumption to establish their prima facie case.

Whatever economists may think about market definition, it is a prerequisite to measuring market shares, and that is how the government wins merger challenges: by measuring market shares and invoking the structural presumption. Moreover, given the extensive case law in this area, the centrality of market definition is quite unlikely to change any time soon, unless Congress enacts new legislation.Footnote 15 Effective merger guidelines must acknowledge this reality.Footnote 16

3.1 Market Definition in Merger Guidelines from 1968 to 2010

The shifting treatment of market definition and market concentration encapsulates the evolution of merger guidelines over the past half century. In the 1968 MGs, the DOJ enforcement policy was “to preserve and promote market structures conducive to competition.” (p. 1) Virtually nothing was stated about analyzing competitive effects. In the 1982 MGs, the focus very much remained on market definition and market concentration, and the hypothetical monopolist test was introduced to define markets, but a more extensive discussion of the non-structural characteristics of markets was added.

Most significantly, in 1982 the DOJ’s enforcement policy shifted away from market structure per se and toward market power: “The unifying theme of the Guidelines is that mergers should not be permitted to create or enhance ‘market power’ or to facilitate its exercise.” (p. 2) The 1992 guidelines moved farther away from market structure as determinative by expanding the discussion of coordinated effects and especially of unilateral effects.

By 2010, most merger challenges applied a theory of harm based on unilateral effects. This was a huge shift from the 1980s when merger enforcement centered on coordinated effects. By 2010, it was well understood that the connection between the level of the HHI and unilateral effects was tenuous at best.Footnote 17 We also knew that the HMT, properly implemented, typically leads to quite narrow markets. Furthermore, government losses often resulted from the courts rejecting the markets defined by the government, either explicitly or implicitly, in favor of a broader market put forward by the merging parties. Together, these factors created an opportunity that was seized by the 2010 HMGs.

The 2010 HMGs adopted a three-pronged strategy to address these challenges and strengthen merger enforcement. First, they added extensive material to explain why markets are often quite narrow, emphasizing that direct evidence of adverse competitive effects informs market definition. In support of this approach, they explained in detail how and why the HMT properly leads to narrow markets, including markets defined around targeted customers.Footnote 18 Notably, if the merged firm would unilaterally impose a significant price increase, then the products sold by the merging firms alone satisfy the HMT. Second, the 2010 HMGs emphasized the importance of direct evidence of adverse competitive effects.Footnote 19 Third, they raised the HHI thresholds to reflect actual enforcement practice, taking the view that the new thresholds would be strong enough in the narrow markets that result from properly implementing the HMT.

Shapiro and Shelanski (2021) show that this strategy has been highly successful, helping the Agencies prevail in challenges to mergers that involved tax preparation software, food distribution, health insurance, office supplies, hospitals, and book publishing, among others. After lax merger enforcement during the Bush Administration, especially following the DOJ’s bruising loss in the Oracle case,Footnote 20 the Agencies won the large majority of their merger challenges during the Obama Administration.

3.2 Market Definition in the 2023 Merger Guidelines

The 2023 MGs abandon this strategy, despite its proven success. They embark in a new direction, shifting sharply from the path taken by the 2010 HMGs. How so?

Section 4.3 of the 2023 MGs lists four methods the Agencies use to define markets: (A) direct evidence of substantial competition between the merging parties; (B) direct evidence of the exercise of market power by a dominant firm; (C) various “practical indicia” with regard to observed market characteristics; and (D) the hypothetical monopolist test.

The 2023 MGs state that methods (A) and (B) “can demonstrate that a relevant market exists in which the merger may substantially lessen competition,” but they indicate nothing about the boundaries of that market. In the language of mathematics, they are existence proofs that do not offer any constructive method for identifying the object that is proven to exist. So far as I can tell, methods (A) and (B) were included so that the Agencies can argue in court that a merger is illegal because it may substantially harm competition in some unspecified line of commerce and section of the country.

The logic and the economics here are perfectly sound.Footnote 21 But I question whether that approach will currently work in practice, given black-letter case law.Footnote 22 In any event, methods (A) and (B) do not help identify the products that are included in the relevant market, so they are not useful for Guideline 1, which requires the government to measure market shares.Footnote 23

For Guideline 1, what matters in practice is how the available evidence is used to identify which products are in the relevant market and which are not. The 2023 MGs offer two methods to do this: the “practical indicia,” where they cite the Brown Shoe case,Footnote 24 and the hypothetical monopolist test, which are listed in that order.

That is a major change from the 2010 HMGs, which offer a single method for defining relevant markets: the hypothetical monopolist test. The 2010 HMGs state: “The Agencies employ the hypothetical monopolist test to evaluate whether groups of products in candidate markets are sufficiently broad to constitute relevant antitrust markets. The Agencies use the hypothetical monopolist test to identify a set of products that are reasonably interchangeable with a product sold by one of the merging firms.” (p. 11). Moreover, Section 4.1.3, “Implementing the Hypothetical Monopolist Test,” made it clear that the Brown Shoe “practical indicia” comprise a list of factors that can be used to implement the HMT, not a separate category of evidence that can be used to define the relevant market without reference to the HMT.

Demoting the HMT is a grave error that will likely undermine effective merger enforcement. The HMT has been an invaluable analytical tool that supports effective horizontal merger enforcement. The HMT has provided a structured method to define relevant markets, so the resulting market shares are informative about likely competitive effects. The HMT is solidly established in the case law and is often used in court by the Agencies to establish narrower markets than the merging firms propose based on the Brown Shoe practical indicia.

The HMT often is essential to the government when it seeks to establish the structural presumption. Most often, the government alleges a properly defined and relatively narrow market based on the HMT, and the merging parties argue for a broader market in which their shares are misleadingly smaller. I therefore find it puzzling and very worrisome that the 2023 MGs demote the HMT.Footnote 25

Compounding the problem, the 2023 MGs remove important language, including examples, from the 2010 HMGs that explains that market shares measured in narrower markets are normally more informative about likely competitive effects than are market shares measured in broader markets. The 2010 HMGs include this passage: “Because the relative competitive significance of more distant substitutes is apt to be overstated by their share of sales, when the Agencies rely on market shares and concentration, they usually do so in the smallest relevant market satisfying the hypothetical monopolist test.” (p. 10) The 2023 MGs use notably weaker language: “the competitive significance of the parties may be understated by their share when calculated on a market that is broader than needed to satisfy the considerations above, particularly when the market includes products that are more distant substitutes, either in the product or geographic dimension, for those produced by the parties.” (p. 49).

The Agencies could have retained the stronger language about narrow markets from the 2010 HMGs without impeding their ability to propose broader markets in cases where they are not relying on market shares and market concentration to infer effects, including when they are applying Guidelines 2, 3, or 4. For example, simply retaining the following passage from the 2010 HMGs would have accomplished that aim: “The hypothetical monopolist test ensures that markets are not defined too narrowly, but it does not lead to a single relevant market. The Agencies may evaluate a merger in any relevant market satisfying the test.” (p. 9–10).

4 Market Concentration Thresholds

The 2023 MGs lower the market concentration thresholds that trigger the Agencies to presume harm to competition. I have been calling for stricter horizontal merger enforcement for many years, so I can support that change, but only if the Agencies really will consistently enforce at or near these levels. If not, then lowering the thresholds will provide misleading guidance and risk undermining the credibility of the Merger Guidelines. After all, the HHI thresholds were raised in 2010 based on the good-government principle that official guidelines should accurately reflect actual Agency practice.Footnote 26

In this section, I examine the changes in the thresholds from 2010 to 2023 and discuss the reasons given for those changes. I then comment on the fact that the 2023 MGs eliminate any safe harbors based on low HHIs. Lastly, I question whether lowering the HHI thresholds will actually lead to more effective merger enforcement.

4.1 Market Concentration Thresholds in the 2023 Merger Guidelines

The 2010 HMGs followed prior guidelines by identifying three zones based on the post-merger HHI and the increase in the HHI caused by the merger: a red zone, a yellow zone, and a green zone. Mergers in the red zone “will be presumed to be likely to enhance market power.” Mergers in the yellow zone “potentially raise significant competitive concerns and often warrant scrutiny.” Mergers in the green zone “are unlikely to have adverse competitive effects and ordinarily require no further analysis.”

In the 2010 HMGs, mergers that increased the HHI by at least 200 and led to a post-merger HHI of at least 2500 were in the red zone. Mergers that increased the HHI by more than 100 and led to a post-merger HHI of more than 1500 but did not fall into the red zone were in the yellow zone. Applying a sliding scale, the Agencies could assert the structural presumption when challenging mergers in either the red zone or the yellow zone, but with stronger force in the red zone. Mergers not in the red and yellow zones were in the green zone.

In the 2023 MGs, a merger that increases the HHI by at least 100 and leads to an HHI of at least 1800 “is presumed to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.” (p. 6).

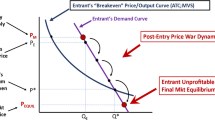

Figure 1 shows how the HHI thresholds have changed from the 2010 to 2023.

As shown in Fig. 1, the 2023 MGs make three changes to the HHI thresholds.

First, mergers in the region with vertical shading have moved from the yellow zone to the red zone. This expansion of the red zone has received by far the most attention.

Under the 2010 HMGs, the Agencies were free to assert the structural presumption when challenging mergers in the yellow zone, so one might think moving a group of mergers from the yellow zone into the red zone is only a minor change. In practice, however, merging parties often argued (contrary to the 2010 HMGs) that mergers not in the red zone were presumptively legal, and the Agencies did not litigate mergers in the yellow zone, so the change could be meaningful.

Here is how the 2023 MGs explain this change: “Although the Agencies raised the thresholds for the 2010 guidelines, based on experience and evidence developed since, the Agencies consider the original HHI thresholds to better reflect both the law and the risks of competitive harm suggested by market structure and have therefore returned to those thresholds.” (p. 6).

The Agencies have not identified the experience and evidence on which they are relying to expand the red zone. I am perplexed about what evidence they have in mind, given that the peer-reviewed literature is not precise enough to support this change.Footnote 27 Moreover, in my experience the significance of HHI metrics depends on how the relevant market is defined and other factors such as the elasticity of demand in that market and the ease or difficulty of entry into that market. Markets for petroleum products are very different from markets for pharmaceutical markets, which are very different from markets for professional services, to give just a few examples.

Second, mergers in the region with horizontal shading are no longer identified as often warranting scrutiny. This weakening of the guidelines is most likely minor, given that the Agencies have not been litigating mergers in the yellow zone. Third, mergers in the region with no shading are no longer identified as unlikely to have adverse competitive effects. I discuss that change below.

The 2023 MGs also introduce a new threshold: a merger that leads to a firm with a market share greater than 30% and increases the HHI by more than 100 is presumed to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.

I favor a structural presumption against mergers involving a dominant firm. Rose and Shapiro (2022) suggest a presumption of harm to competition when a firm with a market share of at least 50% acquires a rival with a market share of at least 1%. “Competition is often harmed when a dominant firm acquires one of its rivals, even a small one. Normally, the dominant firm has abundant internal capabilities, so the acquisition is not needed for it to be strong competitor.”

The 2023 MGs justify the new 30%/100 threshold solely based on the Supreme Court’s Philadelphia National Bank decision, quoting this sentence from that case: “Without attempting to specify the smallest market share which would still be considered to threaten undue concentration, we are clear that 30% presents that threat.” That covers the 30% figure, but what is the basis for using an increase in the HHI of 100? The market shares of the merging firms in Philadelphia National Bank were roughly 20% and 15%, so the increase in the HHI in that case was about 600, not 100. This is not a small discrepancy.

But there is more.

Immediately following the quoted sentence, the Supreme Court states: “Further, whereas presently the two largest banks in the area (First Pennsylvania and PNB) control between them approximately 44% of the area’s commercial banking business, the two largest after the merger (PNB-Girard and First Pennsylvania) will control 59%. Plainly, we think, this increase of more than 33% in concentration must be regarded as significant.” That is a second major discrepancy between the 2023 MGs and Philadelphia National Bank.

To illustrate, consider a market in which the two largest firms each have a market share of 30% and one of them seeks to acquire a firm with a 2% share. That merger would trigger the presumption in the 2023 MGs because the HHI would rise by 120, but the merger would only cause a 3% increase in the two-firm concentration ratio (from 60% to 62%) – far below the 33% increase (from 44% to 59%) that the court regarded as significant.

All of this serves to highlight the dangers that are associated with relying on case citations rather than economic reasoning or empirical evidence.

4.2 Removal of the Safe Harbors

As noted above, the 2023 MGs make another major change: They eliminate the green zones in the 2010 HMGs, which are commonly known as the “safe harbors.” The 2010 HMGs state:

-

Small Change in Concentration: Mergers involving an increase in the HHI of less than 100 points are unlikely to have adverse competitive effects and ordinarily require no further analysis.

-

Unconcentrated Markets: Mergers resulting in unconcentrated markets are unlikely to have adverse competitive effects and ordinarily require no further analysis.

Similar but smaller safe harbors were in the merger guidelines from 1982 to 2010.Footnote 28

The 2023 MGs provide no safe harbors based on market concentration. In this critical respect, the 2023 MGs do not merely revert to the HHI red zones used from 1982 until 2010.

My understanding is that the Agencies removed the safe harbors to give themselves the freedom to argue in court that a merger between two firms with low market shares may substantially harm competition. To see how this might work, suppose that the government demonstrates that there is substantial competition between the merging firms. Guideline 2 asserts that this finding is sufficient to raise prima facie concerns.

But the case law requires that the government define a relevant market in which that harm takes place. Method (A) of market definition in Sect. 4.3 is designed to fit this situation; it asserts that some market must exist in which the harm to competition occurs. Suppose that the government invokes method (A) to meet that legal requirement. Next, suppose that the merging firms put forward a plausible relevant market in which the market shares of the merging firms are small. The government would then be forced to argue that those low shares are irrelevant given the substantial competition between the merging firms that will be eliminated by the merger. At that point, the lack of any safe harbor becomes critical.

I am skeptical that this strategy will be successful, even for mergers that may substantially harm competition and should be blocked. I say this because I have difficulty seeing a federal judge blocking a merger between two firms with single-digit market shares in a market where the HHI is, say, less than 1000. That simply does comport with my experience as an expert witness for the government in multiple merger cases. But that is the strategy that the 2023 MGs appear to adopt, at least in the alternative.

In 2010, we adopted a very different strategy to deal with this type of case. We fully integrated the treatment of unilateral effects with market definition and emphasized that the HMT often leads to narrow markets. Typically, if the evidence shows substantial competition between the merging firms, the merger will cause significant upward pricing pressure, and the HMT will indicate that there is a properly defined relevant market in which the merger will result in a monopoly.

By design, Example 5 in the 2010 HMGs makes precisely this point, using rock-solid economics. The government can put forward that relevant market or perhaps a somewhat broader one, which will also satisfy the HMT. As emphasized above, narrow markets are the path to victory for the government – not low HHI thresholds. As bonuses, the strategy taken in the 2010 HMGs makes use of the sliding scale for HHI metrics and does not conflict with safe harbors.

Moreover, the absence of safe harbors in the 2023 MGs may end up weakening merger enforcement by undermining the structural presumption. How so? The 2023 MGs include this statement: “The higher the concentration metrics over these thresholds, the greater the risk to competition suggested by this market structure analysis and the stronger the evidence needed to rebut or disprove it.” (p. 6) Fundamentally, the government is arguing that HHI metrics are informative regarding the likelihood and magnitude of harm to competition, with higher figures raising greater concerns. Given that long-held view, which is well established in the case law, it will be awkward if not impossible for the government to argue that far lower HHI metrics do not indicate fewer concerns. Courts may respond to this inconsistency by further weakening the structural presumption.

The logic in the 2023 MGs is the flip side of the weak argument that we heard in 2010 that urged us to remove the structural presumption entirely from the merger guidelines. We were told that safe harbors were justified and important – low HHI metrics imply that a merger will not harm competition – but the structural presumption should be eliminated – high HHI metrics are uninformative. Notably, the Antitrust Section of the American Bar Association filed comments recommending that the structural presumption be removed from the guidelines. “As it did in its initial comments, the Section urges the Agencies to remove the presumption of illegality keyed to the level and increase in the HHI.”Footnote 29 In 2010, we found this argument unconvincing and rejected it. The structural presumption plays a central role in the 2010 HMGs.

4.3 Will Lowering HHI Thresholds Matter Much in Practice?

Many observers who are not steeped in antitrust quite naturally focus their attention on the most visible numerical metric found in the merger guidelines: the market concentration thresholds that trigger the structural presumption. Observing that the 2023 MGs expand the red zone by lowering the HHI thresholds that trigger the structural presumption, they presume that this signals stricter merger enforcement. That has certainly been the message from the Agencies.

I agree that lower HHI thresholds signal stricter enforcement, but for three reasons I question whether the net result of the changes made in 2023 will actually be stricter enforcement.

First, even if the Agencies enforce at the lower HHI levels, the net result might be less strict merger enforcement if the changes in market definition discussed above undermine the ability of the Agencies successfully to define narrow markets with the use of the HMT. In my experience, merger cases are far more often won or lost based on market definition than based on HHI levels.

Second, the structural presumption operates using a sliding scale. “The more compelling the prima facie case, the more evidence the defendant must present to rebut it successfully.”Footnote 30 Therefore, only a relatively weak presumption of harm will be afforded to the government in cases where the HHI levels are above but near the new thresholds. Whether the courts will apply a stronger presumption for higher HHI levels by virtue of the 2023 MGs having lowered the HHI thresholds remains to be seen. If so, the lower thresholds will help with stricter enforcement.

To illustrate what is at stake, here are the HHI figures for mergers in a symmetric market:

Number of firms before merger | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pre-merger share of each firm | 50% | 33% | 25% | 20% | 17% | 14% | 13% | 11% | 10% |

Pre-merger HHI | 5000 | 3333 | 2500 | 2000 | 1667 | 1429 | 1250 | 1111 | 1000 |

Increase in HHI | 5000 | 2222 | 1250 | 800 | 556 | 408 | 313 | 247 | 200 |

Post-merger HHI | 10,000 | 5556 | 3750 | 2800 | 2222 | 1837 | 1563 | 1358 | 1200 |

Using the 2010 HHI levels, a 5-to-4 merger triggers the structural presumption, but a 6-to-5 merger does not. Using the 2023 HHI levels, a 7–6 merger triggers the structural presumption. However, I doubt that many federal judges would apply much of a presumption (if any) based on market structure in a merger between two 14% firms unless there was evidence of prior coordination in the market. The merging parties would point out that customers will still have five other good choices and argue that coordination will be hard among six firms.

My views are no doubt influenced by my experience in the 4-to-3 merger between T-Mobile and Sprint, where I testified on behalf of a group of states that opposed the merger. The judge agreed that the states had established their prima facie case but nonetheless ruled in favor of the merging parties based on efficiencies that were asserted by the merging parties and the divestiture of some assets.Footnote 31

Third, we do not need to speculate about what merger enforcement looks like when the merger guidelines employ the HHI thresholds for the structural presumption found in the 2023 MGs. Those HHI thresholds were operative from 1982 until 2010.Footnote 32 Shapiro and Shelanski (2021) examine the HHI levels that were asserted by the government in all of the merger challenges that were litigated by the Agencies between 2000 and 2010. They find only two cases in which the asserted HHIs were below the thresholds adopted in 2010. “In each case the FTC lost its motion to enjoin the transaction because the district court rejected key aspects of the agency’s market definition.” (p. 64) This historical experience does not support the view that lowering the HHI thresholds to their previous levels will strengthen merger enforcement.

Furthermore, in practice the HHI levels for litigated mergers are typically far above the thresholds found in the merger guidelines. Table 2 in Shapiro and Shelanski (2021) shows that the average post-merger HHI in mergers litigated during the 2000–2010 period was 6535 and the average increase in the HHI was 1987. Clearly, during that period there was a yawning gap between actual enforcement and the HHI thresholds in the then-operative 1992 HMGs. Indeed, when the Agencies raised the HHI thresholds in 2010, the stated reason was to close the gap between the guidelines and enforcement reality and thus foster transparency.Footnote 33 The gap did indeed narrow over the subsequent decade, but the HHI metrics for litigated mergers did not decrease by much. Table 2 in Shapiro and Shelanski (2021) shows that the average post-merger HHI during 2010–2020 was 5805 and the average increase in the HHI was 1938.

Examining these figures, one may wonder why the HHI levels for litigated mergers have remained so high for so long. In answering this question, one should bear in mind that here, as in other areas of the law, the litigated cases are a small, non-random sample from the universe of comparable disputes. They tend to be the disputes in which the litigating parties differ substantially in how they assess their prospects in court, as explained by Priest and Klein (1984).

Here are some of the leading reasons why this happens in merger litigation: the acquiring firm was warned about antitrust risk but proceeded ahead anyway, perhaps out of hubris; the legal advice given to the acquiring firm downplayed the antitrust risk; the legal advice given to the target firm downplayed the antitrust risk so the target did not insist on a large breakup fee; the acquiring company dreamed of large synergies from the deal, making the antitrust risk worth bearing; competition was weakened during the merger investigation and litigation, so the merger attempt raised joint profits even though the merger was blocked; or the Agency decided to be unexpectedly aggressive, e.g., by defining the market narrowly.

Market definition is often the central litigated issue in cases where the government asserts very high HHIs, as they typically do. To see how this happens, suppose that the government decides to bring an enforcement action. If the relevant market is fairly clear, the government may well enter into a consent decree with the merging parties under which they divest some assets and the merger proceeds. Litigation tends to result if the government believes it can establish a narrow market in which the HHIs are very high while the merging parties believe the court will reject that narrow market.

The merging parties may find it worth litigating because they have a good chance of winning based on market definition.Footnote 34 For precisely this reason, the ability of the government to prevail in cases where the HMT properly leads to a narrow market is far more important for effective merger enforcement than are the HHI thresholds, as was emphasized above.

The Biden Administration has taken the position that antitrust enforcement generally – and merger enforcement in particular – have been far too lax during the past 40 years. Under this view, the high HHI levels in litigated mergers from 2000 to 2020 reflect policy decisions made by the Bush, Obama, and Trump administrations to under-enforce Section 7 of the Clayton Act. As a test of that hypothesis, one can examine the HHI levels in mergers that have been litigated since President Biden took office. If the Biden Administration was constrained by the HHI thresholds in the 2010 HMGs, one should see a sharp drop in the HHI levels of litigated mergers starting in 2021, which would close the large gap between litigated cases and the HHI thresholds in the 2010 HMGs.

That is not what the data show. Table 1 reports the HHI levels that were asserted by the government for all of the horizontal mergers that were litigated by the Biden Administration for which a complaint was filed as of February 2024. The gap between the HHI levels and the 2010 HHI thresholds has remained very large during the Biden Administration. The data shown in Table 1, combined with the mixed record of success in these merger challenges, strongly suggests that horizontal merger enforcement in the Biden Administration has not been constrained by the HHI thresholds in the 2010 HMGs.

5 How Can Harmful Mergers Most Effectively Be Deterred?

To understand fully the 2023 Merger Guidelines, one must view them in the context of the overall antitrust enforcement policy articulated by the Biden Administration. This is especially true because the White House has been more vocal about antitrust enforcement in the Biden Administration than in recent administrations – including by pointedly issuing an Executive Order that instructed the Agencies to update the merger guidelines.

Numerous statements made by Biden Administration officials, including by President Biden himself, assert that antitrust policy for the past 40 years has been a failed experiment in laxity. Here is a passage from President Biden’s 2021 Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy:

“Robust competition is critical to preserving America’s role as the world’s leading economy. Yet over the last several decades, as industries have consolidated, competition has weakened in too many markets, denying Americans the benefits of an open economy and widening racial, income, and wealth inequality. Federal Government inaction has contributed to these problems, with workers, farmers, small businesses, and consumers paying the price.”Footnote 35

And here is what President Biden said when he announced that Executive Order:

“We’re now 40 years into the experiment of letting giant corporations accumulate more and more power. And where — what have we gotten from it? Less growth, weakened investment, fewer small businesses. Too many Americans who feel left behind. Too many people who are poorer than their parents. I believe the experiment failed.”Footnote 36

The leaders appointed by President Biden to run the antitrust agencies have made similar statements, including ones criticizing merger enforcement as being overly lax for decades. For example, FTC Chair Lina Khan offered this view on merger enforcement:

“Evidence suggest that decades of mergers have been a key driver of consolidation across industries, with the latest merger wave threatening to concentrate our markets further yet…. While the current merger boom has delivered massive fees for investment banks, evidence suggests that many Americans historically have lost out, with diminished opportunity, higher prices, lower wages, and lagging innovation.”Footnote 37

While I consider the rhetoric of the Biden Administration to be overstated – going far beyond what the evidence actually shows – I agree that stricter horizontal merger enforcement would be desirable. Indeed, I have been advocating for that for many years: in my writings, including Farrell and Shapiro (1990, 2010) and Baker and Shapiro (2008a, b); in my work on the 2010 HMGs; and in my testimony as an expert witness on behalf of the DOJ, the FTC, a group of state attorneys general, and a private plaintiff in a number of merger challenges since I left the Obama administration and returned to Berkeley in 2012.

The remainder of this article asks whether the 2023 MGs are likely to be effective at achieving the Biden Administration’s goal of stopping many more harmful mergers from happening.

The starting point in answering the question is to recognize that effective merger enforcement, as in many other areas of law enforcement, must be based on deterrenceFootnote 38 This point should not be in dispute, given the data that we have on merger enforcement.

During Fiscal Year 2022, 3029 mergers eligible for a “second request” for more information were reported to the Agencies under the Hart-Scott-Rodino (“HSR”) Act.Footnote 39 The Agencies issued second requests for only 1.6% of those mergers (47 out of 3029).Footnote 40 For years, the Agencies have consistently issued about 50 such second requests per year. That figure is determined by resource constraints and the efficiency with which Agency resources are deployed. In practice, the Agencies can look closely at only a very small fraction of proposed mergers, so merger enforcement relies very heavily on deterrence.

As a general principle, law enforcement is effective if enforcement resources are deployed so as to deter harmful conduct without imposing unnecessary costs on beneficial or benign conduct. Applied to mergers, this means focusing DOJ and FTC resources on the mergers that are most likely to substantially lessen competition so as to deter them without raising the costs or the risks that are associated with mergers that have no real prospect of harming competition. In other words, in order to be effective, merger enforcement should be well targeted.

The targeting of merger enforcement has been accomplished in several imperfect ways.

First, the HSR Act itself imposes filing requirements only on certain transactions. Most notable is the “size-of-transaction” threshold, which is $119.5 million in 2024. This form of targeting is simple but imperfect because some anticompetitive mergers fall below the threshold and merging firms can game the system to some degree, as shown convincingly by Wollman (2019).

Second, the Agencies have historically focused their resources on the mergers that are most likely to harm competition. Choosing wisely the mergers for which second requests are issued is critical, given how resource-intensive each second request is for the Agency and given how hard it would be later to challenge a consummated merger for which no second request was issued.

The Merger Guidelines matter a lot for this critical task. They are used to train and guide Agency staff. Partly because fewer than 3% of HSR filings receive a second request, the Agencies rarely challenge mergers that do not substantially increase concentration in a highly concentrated market. The business community and their antitrust advisors are well aware of this fact, which is driven by resource constraints at the Agencies combined with litigation realities.

Third, the merger guidelines have informed the business community of the deals that the Agencies would not challenge as well as those that they would. The 2010 HMGs sought to provide the public with usable guidance so as to deter harmful mergers without imposing unnecessary costs or risk on mergers that are unlikely to lessen competition substantially. The following statement from the first page of 2010 HMGs reflects that goal “The Agencies seek to identify and challenge competitively harmful mergers while avoiding unnecessary interference with mergers that are either competitively beneficial or neutral.”Footnote 41

No comparable statement can be found in the 2023 Merger Guidelines. Instead, they cite the Supreme Court for the proposition that efficiencies “cannot be used as a defense to illegality.”

I read the 2023 MGs as reflecting a foundational belief that mergers that involve large firms are generally undesirable. This belief seems to be based on a deep skepticism that such mergers generate meaningful social benefits. I do not believe the evidence supports such an extreme view, but my point here is simply that the 2023 MGs do not target their fire. As a leading example, the removal of safe harbors based on market concentration seems designed to increase the antitrust risk for a great many horizontal mergers so as to deter more of them.

The lack of targeting in the 2023 MGs is even more profound because they apply to all mergers – not just horizontal mergers. Indeed, they apply to all asset acquisitions, including those used for internal growth, product improvements, and innovation and those used to enter and disrupt markets in which the acquirer does not (yet) participate. Adding risk this widely is troubling.

Consistent with this skeptical view of mergers, the Agencies have taken two other significant actions that impose costs and delays on all mergers that are subject to the HSR Act – not just those that are most likely to harm competition, and not just those that receive second requests.

Early Terminations: Under the HSR Act, the Agencies may grant “early termination” to a merger, which allows the merger to be consummated without waiting the full 30 days that are specified in the statute for the Agencies to decide whether to issue a second request for information so that they can conduct an in-depth investigation of the merger. In FY2020, 1133 deals requested early termination, of which 861 (76%) were granted.Footnote 42 Very early in the Biden Administration, the Agencies effectively stopped granting early terminations.Footnote 43 In FY 2022, 1345 deals requested early termination, and only five (0.4%) were granted. Clearly, the resulting delays are not well-targeted at harmful mergers.

HSR Filing Requirements: In 2023, the FTC issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“NPRM”) that would greatly expand the HSR reporting requirements.Footnote 44 The FTC estimates that these changes will cost merging firms roughly $100,000 per deal, which sums to about $350 million per year in total.Footnote 45 This figure is hotly disputed. The FTC’s NPRM generated a furious response from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Based on a survey of antitrust practitioners that it conducted, the Chamber stated: “Those survey responses overwhelmingly indicate that the FTC has vastly underestimated the burdens associated with the NPRM.”Footnote 46 The new reporting requirements apply to all HSR filings, which makes them very poorly targeted. The FTC states: “Many of the proposed changes would increase the burden on all filers.” In FY2022, of the 1779 reported transactions of size less than $500 million, only 12 received second requests. The lack of targeting applies both to the compliance costs for merging firms and to the agency resources that are needed to review those fatter filings.

Poor targeting arises with respect to the type of transaction as well as the size of the transaction. At least 88% of HSR-reportable transactions do not involve a merger between actual or potential competitors.Footnote 47 Adding costs and risk to all reportable non-horizontal transactions is very poorly targeted to harmful mergers, given that non-horizontal mergers as a category are inherently less worrisome than are horizontal mergers. I hope that this basic proposition is not now in dispute.

The lack of targeting by transaction type is consistent with a belief by current Agency leaders that many more non-horizontal mergers need to be deterred or blocked to prevent large and powerful firms from expanding their operations into new markets. That belief appears to undergird Guideline 6 in the 2023 MGs and especially Section 2.6A, “Extending a Dominant Position into Another Market.” In my view, the empirical evidence with respect to non-horizontal mergers does not support such beliefs.

Further evidence that current Agency leaders are suspicious of large firms that seek to expand into adjacent markets through acquisition can be seen in this bald assertion in the 2023 MGs (p. 11): “In general, expansion into a concentrated market via internal growth rather than via acquisition benefits competition.” That is not how I read the extensive economic literature about the economics of innovation. Often, large and successful firms can expand into adjacent markets and inject competition into those markets more rapidly and more effectively through acquisitions – perhaps small “toehold” acquisitions – than through internal growth. Given the very sizeable variation in efficiency across firms, these acquisitions can be highly pro-competitive.

My concern with these policy changes is not that they seek to strengthen horizontal merger enforcement – which is a goal that I support – but that they seek to do far more in a blunt and inefficient way. For example, why did the FTC conduct an extensive review of the Amazon/MGM transaction, for which there did not appear to have been any good theory of harm? The inefficient use of Agency resources reduces deterrence and allows more harmful mergers to go undetected. This was a tangible problem during the 2021–2022 merger wave.Footnote 48

Furthermore, poorly targeted merger enforcement is costly for our economy and needlessly energizes powerful forces that oppose effective antitrust enforcement. The Economist recently wrote that “the single biggest reason why Bidenomics has got a bad rap has been his competition agenda.” They elaborated: “The FTC has introduced new merger-review guidelines that require regulators to scrutinise just about any deal that makes big companies bigger, which could produce even more contentious competition policy. Excessive scrutiny of deals would also use up regulators’ scarce resources and poison the atmosphere for big business.”Footnote 49

Here is a story to illustrate how the 2023 MGs might deter pro-competitive deals by ambitious, mid-sized firms. Imagine that you are the CEO of a mid-sized company that is efficient and innovative. You are considering expanding into a new market through a $250 million acquisition, your biggest ever. The target company is not a rival of yours, but you have heard that the DOJ and the FTC are feisty these days and are applying new, tougher standards for all deals. You seek legal advice. Your lawyers read the 2023 MGs, where they find several theories of harm that could be applied to your transaction and nothing at all to ease their concerns. They warn you about the antitrust risk. They also inform you that a second request will cost $15 million and delay the deal for 6–12 months even if the government ends up not challenging it. You soon learn that the target company has received similar advice on antitrust risk and insists on a $25 million break-up fee if the deal is blocked by regulators. You walk away from the deal, giving up on your plans to expand into the new market.

Two other aspects of the 2023 MGs heighten my concern that they will not be effective in deterring and blocking harmful mergers.

First, the 2023 MGs depart from previous merger guidelines by rooting their authority in the Agencies’ interpretation of the case law rather than in economic principles that are consistent with the statute and the evolving case law. By shifting the emphasis from economic principles that are consistent with the case law to a recitation of mostly outdated and often superseded case citations, the Agencies have ceded the high ground – the “principal analytical techniques” that were explained in prior Merger Guidelines – where the Agencies’ experience and deep expertise is likely to command the most respect from the courts.Footnote 50

Second, the 2023 MGs do very little to enhance their credibility. They never acknowledge that mergers can and do create benefits for the public. I wonder whether federal judges will accept the 2023 MGs as persuasive authority as they have done with the 2010 HMGs.Footnote 51

6 Conclusion

The 2023 Merger Guidelines include some valuable and welcome updates to the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines. However, their treatment of market definition may weaken horizontal merger enforcement, and they are not well targeted at harmful mergers.

Notes

For an incisive critique of the treatment of market definition in the 2023 MGs, see Kaplow (2024) in this volume.

See Shapiro and Yurukoglu (2024).

Shapiro (2023) identified a number of major flaws in the Draft MGs and explained why merger enforcement based on those Draft MGs would have been less accurate and less effective than it had been under the 2010 HMGs.

“Most merger analysis is necessarily predictive, requiring an assessment of what will likely happen if a merger proceeds as compared to what will likely happen if it does not. Given this inherent need for prediction, these Guidelines reflect the congressional intent that merger enforcement should interdict competitive problems in their incipiency and that certainty about anticompetitive effect is seldom possible and not required for a merger to be illegal.”.

See Salop (2024).

Federal Trade Commission vs. Actavis, 133 S. Ct. 2223 (2013) at 2236.

Federico et al. (2020) explain how this approach works, both in theory and in practice, to evaluate mergers that may harm dynamic competition and innovation.

United States v. Marine Bancorp., 418 U.S. 602 (1974).

The FTC challenged Meta’s acquisition of Within. The FTC argued that Meta was a potential entrant into the market for virtual reality dedicated fitness apps, in which the Supernatural app that was owned by Within had an 82% share of revenue. The District Court found that the FTC had failed to show that Meta had a “reasonable probability” of entering the market if not for the merger. Critically, the Court stated: “The Court accordingly holds that the ‘reasonable probability’ standard—as clarified by the Fifth Circuit to suggest a likelihood noticeably greater than fifty percent—is the standard of proof that the FTC must present.” FTC v. Meta Platforms, 654 F. Supp 3d 892, 927 (2023).

Making matters worse, the Supreme Court has hindered enforcement that relates to multi-sided platforms with a poorly reasoned and widely criticized opinion. See Ohio v. American Express, 138 S. Ct. 2275 (2018). The dissent by Justice Breyer eviscerates the majority opinion by Justice Thomas.

More accurate would be to state that the platform operator has mixed motives. One of the basic economic ideas with regard to multi-sided platforms is that platform operators make strategic decisions to attract participants on one “side” or another. For example, a newspaper attracts users with costly content and low subscription prices in order to make more money from the advertisements that the newspaper sells. The mix of space that is devoted to costly content versus paid advertising involves tradeoffs between subscribers and advertisers. This is not a “conflict of interest” as that term is normally used.

Mergers of competing employers is one of the three areas where Rose and Shapiro (2022) recommend changes.

Federal Trade Commission v. Kroger and Albertsons, February 26, 2024.

United States v. Philadelphia National Bank, 374 U.S. 321 (1963).

Ironically, language that Congress adopted to give Section 7 of the Clayton Act very broad reach is now used by merging parties to erect an obstacle to merger enforcement. The statute prohibits asset acquisitions that may substantially lessen competition “in any line of commerce or in any activity affecting commerce in any section of the country.” Somehow (!) the courts have interpreted this broad, inclusive language to impose a requirement that the government establish a relevant market in which the harm to competition takes place. For further discussion of these issues, see Kaplow (2024) in this volume.

The 2021 Merger Assessment Guidelines issued by the U.K. Competition and Markets Authority illustrate how merger enforcement can evolve if less constrained by rigid case law. In those guidelines, market definition has been reduced to a vestigial role. Market definition has been relegated to a few pages at the very end of those guidelines, where this statement can be found: “the assessment of the relevant market is an analytical tool that forms part of the analysis of the competitive effects of the merger and should not be viewed as a separate exercise.” ¶9.1.

In markets for homogeneous products, the increase in the HHI can be informative about competitive effects; the level of the HHI is less informative. In markets with differentiated products, the increase in the HHI can be a good proxy for unilateral price effects, at least under the strong assumption of (flat) logit demand. See Nocke and Whinston (2022). The 2010 HMGs state: “The Agencies rely much more on the value of diverted sales than on the level of the HHI for diagnosing unilateral price effects in markets with differentiated products.” (p. 21).

This theme is suffused throughout the 2010 HMGs. Here are a few illustrative passages from Sect. 4, Market Definition. Example 4 explains why including cars in the market when evaluating a merger between motorcycle makers would be a mistake, stating: “Evaluating shares in a market that includes cars would greatly underestimate the competitive significance of Brand B motorcycles in constraining Brand A’s prices and greatly overestimate the significance of cars.” (p. 9) Example 5 demonstrates that Products A and B can satisfy the HMT even if two-thirds of the sales lost when Product A raises is price are diverted to other products. (p. 10) “Evidence of competitive effects can inform market definition, just as market definition can be informative regarding competitive effects.”.

(p. 9) “Where analysis suggests alternative and reasonably plausible candidate markets, and where the resulting market shares lead to very different inferences regarding competitive effects, it is particularly valuable to examine more direct forms of evidence concerning those effects.” (p. 9) “Defining a market broadly to include relatively distant product or geographic substitutes can lead to misleading market shares. This is because the competitive significance of distant substitutes is unlikely to be commensurate with their shares in a broad market.” (p. 10) “Market shares of different products in narrowly defined markets are more likely to capture the relative competitive significance of these products, and often more accurately reflect competition between close substitutes. As a result, properly defined antitrust markets often exclude some substitutes to which some customers might turn in the face of a price increase even if such substitutes provide alternatives for those customers.” (p. 10) “Relevant antitrust markets defined according to the hypothetical monopolist test are not always intuitive and may not align with how industry members use the term ‘market.’” (p. 11) “Groups of products may satisfy the hypothetical monopolist test without including the full range of substitutes from which customers choose. The hypothetical monopolist test may identify a group of products as a relevant market even if customers would substitute significantly to products outside that group in response to a price increase.” (p. 12). “If prices are negotiated individually with customers, the hypothetical monopolist test may suggest relevant markets that are as narrow as individual customers.” (p. 17).

Adding Sect. 2, “Evidence of Adverse Competitive Effects,” was radical at the time: previous merger guidelines had all started with market definition and market concentration. The 2010 HMGs also updated and expanded the treatment of unilateral effects, including price effects, bargaining, and innovation, emphasizing that a merger between two significant competitors may substantially harm competition even if those firms also face other significant rivals. Critically, the 2010 HMGs harmonized and integrated the treatment of market definition and the analysis of competitive effects. A lack of harmony had undermined merger enforcement prior to 2010.

United States vs. Oracle Corp., 331 F. Supp. 2nd 1098 (2004).

See Farrell and Shapiro (2010) on the use of upward pricing pressure as an alternative to market definition.

Short of legislation, only the Supreme Court can get us out of this cul-de-sac by stating that market definition is not required in merger cases if direct evidence demonstrates harm, and getting a merger case in front of the Supreme Court is not easy to do. Furthermore, the Supreme Court has recently embraced market definition as an obstacle that antitrust plaintiffs must overcome, even in cases where there is direct evidence of harm. See Ohio v. American Express, 138 S. Ct. 2275 (2018). The current Court seems unlikely to ease the path for government merger challenges by treating market definition as a tool used to measure market shares in cases where the government chooses to invoke the structural presumption rather than an initial hurdle that the government must clear to have a viable case.

Kaplow (2024) develops this point further, asking whether the Agencies have relied more on market definition or moved away from market definition, or somehow both, in the 2023 MGs.

Brown Shoe v. United States, 82 S. Ct. 1502 (1962).

The Agencies may believe they are giving themselves more flexibility in how they define markets. But when they go to court, that very flexibility – one might say vagueness – will work in favor of the merging parties, not the government, raising the risk that courts will accept overly broad relevant markets and approve harmful mergers.

Christine Varney, An Update on the Review of the Horizontal Merger Guidelines, January 26, 2010.

Nocke and Whinston (2022) explain why the increase in the HHI is much more informative for predicting unilateral effects than is the level of the HHI. Kaplow (2024) shows that the unilateral effects that are associated with a merger can vary widely, for a given level and increase in the HHI, depending on how the relevant market is defined and on the elasticity of demand in that market. Shapiro and Yurukoglu (2024) discuss the evidence from merger retrospectives, which also does not provide a basis for the expanded red zone in the 2023 MGs.

The 1982 MGs stated that “the Department is unlikely to challenge” mergers meeting any of the following three conditions: (1) the post-merger HHI is less than 1000; (2) the increase in the HHI is less than 100 and the post-merger HHI is less than 1800; and (3) the increase in the HHI is less than 50. The 1992 HMGs retained these same three safe harbors but said that these mergers “are unlikely to have adverse competitive consequences and ordinarily require no further analysis.” Shapiro (2010) points out that under the 1982 MGs and the 1992 HMGs, the safe harbor zone and the zone in which mergers are presumed to harm competition touch at the point where the post-merger HHI is 1800 and the increase in the HHI is 100. The 2010 HMGs eliminated that anomaly.

American Bar Association, Antitrust Section, HMG Revision Project – Comment, June 4, 2010.

United States v. Baker Hughes, 908 F. 2d 981 (DC Circuit, 1990).

New York v. Deutsche Telecom, 439 F. Supp 3d 179 (2020).

The 1982 MGs and the 1992 HMGs also included a yellow zone, which is not present in the 2023 MGs. The yellow zone allowed the Agencies to assert the structural presumption against mergers at lower HHI levels and lower HHI changes. This added option makes the argument in the text even stronger.

See Christine Varney, An Update on the Review of the Horizontal Merger Guidelines, January 26, 2010 and Shapiro (2010).

The merging firms also can win by rebutting the structural presumption, e.g., based on entry or efficiencies. In recent years, the government and the merging firms are increasingly litigating over the adequacy of the divestiture package or “fix” that the merging firms have offered.

Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, July 9, 2021, Sect. 5.

Remarks by President Biden At Signing of An Executive Order Promoting Competition in the American Economy, July 9, 2021.

Lina Khan Remarks Regarding the Request for Information on Merger Enforcement, January 18, 2022, p. 2 (footnotes omitted).

See Baer et al. (2020, p. 25): “Building a successful enforcement program that restores deterrence should be the central antitrust objective of the next administration.”.

Hart-Scott-Rodino Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2022, Appendix A. This is the most recent annual HSR report.

The 1.6% figure for FY2022 was the lowest in at least a decade. This figure is more normally in the 2.5% to 3.5% range. See Appendix A. The 1.6% figure for FY22 was pulled down by an unusually large number of HSR filings.

This statement replaced the following one from the 1992 HMGs (p. 3): “While challenging competitively harmful mergers, the Agency seeks to avoid unnecessary interference with the larger universe of mergers that are either competitively beneficial or neutral.” The same basic idea can be found in the 1982 MGs (p. 1): “By stating its policy as simply and clearly as possible, the Department hopes to reduce the uncertainty associated with enforcement of the antitrust laws in this area.”.

HSR Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2022, Appendix A. This same source shows that a similar fraction of the requests for early termination were granted in every year for at least the prior decade.

FTC, DOJ Temporarily Suspend Discretionary Practice of Early Termination, February 2, 2021.

Premerger Notification; Reporting and Waiting Period Requirements, June 29, 2023.

For comparison, the HSR filing fee for a transaction size between $173 million and $536 million is $105,000.

See U.S. Chamber of Commerce (2023), which estimates the extra direct costs at $1 billion to $2 billion per year. Based on input from current FTC staff who had previously prepared HSR filings while in private practice, the FTC estimated that the proposed changes would on average increase the time required for merging firms to prepare their responses by 107 h.

Table XI in the Hart-Scott-Rodino Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2022 reports that the acquiring company and the acquired company derived revenues from the same 3-digit NAICS industry in only 12% of the reported mergers (364 out of 3029). This overstates the number of horizontal mergers because 3-digit NAICS industries typically include many products and services that are not substitutes and because a merger was counted as “intra-industry” if the merging firms both received any revenue from the same 3-digit NAICS industry.

Figure 1 in the HSR Annual Report for FY2022 shows HSR filings for FY 2013 through FY2022. The largest number of HSR filings prior to FY2021 was 2111 in FY2018. The number of HSR filings in FY2021 was 3520, and the number of HSR filings in FY2022 was 3152. Targeting second requests was especially important for those years.