Abstract

I study the relationship between competition and price dispersion by evaluating the competitive role of “ultra-low-cost carriers” (ULCCs) in the U.S. airline industry. These carriers have significantly lower unit costs than do traditional “low-cost carriers” (LCCs), and the ULCCs focus almost exclusively on leisure travelers, and offer unbundled products with low base fares and fees for many ancillary services. Public statements in carriers’ earnings calls from 2012 to 2019 indicate that “legacy carriers” responded to ULCC expansion by increasing fare segmentation and further reducing fares at the bottom of the fare distribution. Using data from 2012Q1 to 2019Q4, I show that ULCC presence significantly widens fare dispersion, whereas competition from legacy carriers and LCCs does not meaningfully affect fare dispersion in most cases. More generally, my results show that failing to account for firm-level heterogeneity could lead to inappropriate conclusions about the relationship between competition and price dispersion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The marketing carrier is the airline that sells tickets for the flight, whereas the operating carrier is the airline that operates the flight. Marketing carriers are often also the operating carrier, but at other times subcontract operations to a regional partner. As such, in research on vertical relations in the airline industry, researchers may instead distinguish between carriers that both market and operate flights (‘majors') and carriers that operate flights but typically do not market them (‘regionals'). For a more thorough discussion, see Forbes and Lederman (2009).

Prior to deregulation, the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Board had widespread authority to regulate route-level entry and prices on interstate routes. During this time, carriers such as Southwest—which operated intrastate routes throughout Texas prior to deregulation—faced prohibitive barriers to entry on interstate routes. For a review of the history of regulatory reform in the U.S. airline industry, see Borenstein and Rose (2014).

For a broader review of price discrimination and price dispersion, see Stole (2007).

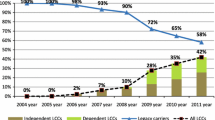

The authors categorize both Allegiant and Frontier as LCCs. Although Spirit is not explicitly mentioned in paper, they appear to be categorized as an LCC as well.

Throughout the paper, I use the term itinerary to refer to a passenger's entire trip from her origin to her destination, and the term segment to refer to individual flights within that trip. For example, a single itinerary from A to B with a connection at H is denoted as A:H:B and consists of two segments—A:H and H:B.

I measure the largest routes by the number of passenger itineraries. A direct route between endpoint airports A and B is often denoted A:B. Research on the airline industry typically defines routes either unidirectionally or bidirectionally, with the former treating A:B and B:A as separate routes and the latter as a single aggregated route.

In the airline industry, average costs and revenues are often total costs (or revenues) divided by total available seat miles, where an available seat mile represents a single seat flown one mile.

I denote fare revenue with an asterisk because a significant share of ancillary revenue for ULCCs during this time came from booking fees that are charged to passengers who book tickets either online or over the phone. These fees were not historically included as part of airfare in USDOT's DB1B database, despite the fees' being paid by the vast majority of passengers. Following a recommendation by USDOT's Office of Inspector General in 2020, the Department directed the Bureau of Transportation Statistics to issue a directive that clarified that such fees are to be included in future reporting.

Conceptually, one could similarly order the three carrier types in terms of their interest in business versus leisure travelers. For example, JetBlue describes its customers as “neither high-traffic business travelers nor ultra-price sensitive travelers” (JetBlue 2019 10-K, p. 6) whereas Frontier states that their “product appeals to price-sensitive customers” and that they are not focused on business travel but do attract “small business travelers who bear their own travel costs” (Frontier 2016 S-1, p. 91).

Three legacy carriers previously attempted to segment their product lines in an effort to compete with LCCs by introducing separate airline brands. United Airlines introduced “Shuttle by United” in 1994 and subsequently “Ted” before shuttering Ted in 2008. Delta Air Lines similarly introduced “Delta Express” in 1996 and subsequently “Song” before shuttering Song in 2006. US Airways' launched “MetroJet” in 1998, but ceased operating under the MetroJet name by 2001.

To document carriers' justifications for introducing the BE fare class as well as the timing of each carrier's BE rollout, I collected transcripts from the earnings calls of all major carriers between 2012Q1 and 2019Q4. Additionally, I supplemented the information that I obtained from these earnings calls with information from other public filings and from presentations by carriers as well as from the news media.

Carriers have long used inter-temporal price discrimination to price discriminate between leisure and business passengers (Escobari, Rupp, and Meskey, 2019). Nonetheless, further segmenting economy fares in addition to maintaining updated strategies of inter-temporal price discrimination could enable carriers to respond better to ULCC competition.

I do not drop JetBlue itineraries coded with first-class segments, because such segments account for the vast majority of JetBlue's itineraries in the DB1B during this time. DB1B fares recorded by legacy carriers and LCCs between $0 and $15 typically represent fares paid for in frequent flyer miles rather than dollars, so the true price is effectively unobserved in the data.

During my period of analysis, the vast majority of direct itineraries are nonstop, but a small share of observations in the earliest years of my analysis include a stop but no change of aircraft.

For example, the share of leisure versus business round-trip passengers on a route between Detroit (DTW) and Las Vegas (LAS) may differ based on whether they originated at DTW or LAS. When Frontier entered this market in 2019Q2, incumbent carriers may have responded differently for DTW:LAS:DTW itineraries than for LAS:DTW:LAS itineraries, so I treat each direction as a separate market.

Additionally, I grouped Phoenix-Mesa Gateway (AZA) alongside Phoenix Sky Harbor International (PHX) and Orlando Sanford International Airport (SFB) alongside Orlando International Airport (MCO) because Allegiant Air rapidly expanded their operations in both locations postdating the period studied by Brueckner, Lee, and Singer (2014).

For metropolitan areas where multiple airports could be considered ‘primary', I chose the airport more central within the metropolitan area as the primary airport.

The sample is restricted to direct routes because the DB1B does not include information on whether a route included an intermediary stop. However, the number of competitors is determined using databases that include information on segments rather than itineraries, and as such correspond to nonstop service. During the sample period, the difference between nonstop and direct service is largely semantic, as the vast majority of direct service was nonstop.

I required routes to have circuity—the ratio of total miles to nonstop miles—below the 95th percentile of the circuity distribution for connecting flights in the DB1B, which was 1.67.

There were two major mergers from 2012 to 2019. US Airways and American Airlines closed their merger in 2013Q4, and retired the US Airways brand in 2015Q4. Virgin America closed their merger with Alaska Airlines in 2016Q4, and retired the Virgin America brand in 2018Q2. In cases where both carriers of a given holding company serve a route simultaneously, I code them as a single competitor.

I refer to the product segmentation that is described in this paper as price discrimination, which applies to situations where two similar products are sold at differing markups over marginal cost; in this regard I am following the definition of Stigler (1987) and used by Varian (1989). Anecdotally, there is significant variation in the price differences among economy product segments, which suggests varying markups over marginal costs. However, whether these differences are sufficient to constitute price discrimination is not entirely clear.

Fares for round-trip itineraries represent the fare per-leg of travel, inclusive of taxes and government-imposed fees, and is assumed to be half the total fare for the round-trip. Rescaling the fare to the total fare for the round-trip itineraries would not affect my results given the structure of my regressions.

Using my network-based definition of connecting competitors, Allegiant does not serve any routes as a connecting competitor, so the dummy variable that represents connecting competition from Allegiant is excluded from all regressions.

To gain some sense of where in the fare distribution seats are more likely to have additional legroom, I pulled archived seat maps for each legacy carrier's Airbus A-320 from SeatGuru.com (a now-defunct former subsidiary of Tripadvisor). In 2017, American allocated 18 of the 138 economy seats to their “Main Cabin Extra” product; Delta allocated 18 of their 141 or 144 to their “Comfort + ” product; and United 42 of their 138 to their “Economy Plus” product.

I include a separate dummy variable to capture the presence of Frontier prior to its transition to the ULCC model, which I denote in the results as “Frontier (LCC)”.

While markets are defined based on unidirectional routes, clustering by bidirectional routes allows for the possibility that standard errors on each direction of the route are correlated with one another.

While I mostly attempt to limit causal language, doing so entirely would result in an excessively verbose discussion, so in the event that language may sound causal this is not my intent.

For example, on November 2, 2022, I searched for flights between Des Moines, IA and Syracuse, NY. This route is not served directly by any ULCCs, and it is unlikely that any legacy carriers would view them as a potential or connecting competitor. Nonetheless, all three legacy carriers offered BE on connecting itineraries from Des Moines to Syracuse.

I defined the date that a rollout was complete based on statements in earnings reports, as is shown in the timeline (Table 3): I code the post-rollout period beginning in 2016Q1 for Delta Air Lines; 2017Q3 for United Airlines; and 2017Q4 for American Airlines. Because neither of the LCCs that introduced BE-like products did so until near the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, I present this analysis only for legacy carriers.

The remaining coefficients are omitted from the table, but are available upon request to the author. Comparing across the three carriers, there is no clear change in the effect of legacy carrier presence on dispersion after the rollout of BE. Evidence for LCCs is mixed across the three legacy carriers in terms of its magnitude and statistical significance.

For example, the U.S. Department of Justice cited such an effect in their suit to block JetBlue's proposed acquisition of Spirit (USDOJ, 2023). As was noted by a reviewer on an earlier draft of this paper, changes to the distribution of fares that are paid by passengers can result from some combination of changes to the support of the fare distribution offered by airlines (for example, reducing the fare floor on a route) and changes in the capacity sold at each mass point of the fare distribution. The price “effects” that are commonly described in the literature do not generally disentangle these two factors.

Given the log-linear specification, the percentage reduction in fares is given by \({e}^{\beta }-1\). Standard errors on marginal effects are computed with the use of the delta method. Marginal effects and their standard errors for specifications on the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles are presented in Table A3 in the Appendix.

I estimated these specifications in log-linear form as it is conventional in the literature on airline competition. The difference in fare pressure that is exerted by LCCs versus ULCCs still results from a linear specification, but the interpretation across the fare distribution differs. ULCC presence is still associated with a greater dollar reduction in fares at the bottom of the fare distribution than at the median of the fare distribution, but the differences are not as striking as when they are compared in percentage terms. On the other hand, LCC presence is associated with greater dollar reductions in fares at the median of the fare distribution than at the bottom of the fare distribution. However, this does not change the broader implication that the fare pressure that is exerted by ULCCs is more concentrated towards the bottom of the fare distribution than is the fare pressure that is exerted by LCCs.

Notably, I considered alternative definitions of connecting competition that were not based on service availability but instead were based on whether a connecting carrier attained either a 5\% or 10\% passenger share. While the passenger share definition has been used in previous work, it poses a clear endogeneity concern as connecting service is more likely to reach a sufficient share of passengers if competitors' nonstop service is abnormally costly in a given quarter. In other words, high contemporaneous fares can cause the connecting competitor variable to shift from 0 to 1 under the passenger share construction, which can result in estimates that suggest connecting competition is associated with higher fares.

Specifically, I estimated specifications with: (1) carrier and route fixed effects; (2) carrier-year-quarter and route-quarter of year fixed effects; and (3) carrier-year-quarter and route-year-quarter fixed effects.

References

Bachwich, A. R., & Wittman, M. D. (2017). The emergence and effects of the ultra-low cost car- rier (ULCC) business model in the US airline industry. Journal of Air Transport Management, 62, 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2017.03.012

Berry, S., & Jia, P. (2010). Tracing the woes: an empirical analysis of the airline industry. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 2(3), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1257/mic.2.3.1

Borenstein, S. & Rose, N. L. (2014). How airline markets work...or Do They? Regulatory reform in the airline industry. In N.L. Rose (Eds.), Economic Regulation and Its Reform: What Have We Learned? (pp. 63–136). University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226138169.001.0001

Borenstein, S., & Rose, N. L. (1994). Competition and price dispersion in the U.S. Airline Industry. Journal of Political Economy, 102(4), 653–682.

Brueckner, J. K., Lee, D., & Singer, E. S. (2013). Airline competition and domestic US Airfares: A comprehensive reappraisal. Economics of Transportation, 2, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecotra.2012.06.001

Brueckner, J. K., Lee, D., & Singer, E. (2014). City-Pairs versus airport-pairs: a market-definition methodology for the airline industry. Review of Industrial Organization, 44, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-012-9371-7

Brueckner, J. K., Lee, D. N., Picard, P. M., & Singer, E. S. (2015). Product unbundling in the travel industry: The economics of airline bag fees. Journal of Economics and Management Strat- Egy, 24(3), 457–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.12106

Brueckner, J. K., Czerny, A. I., & Gaggero, A. A. (2021). Airline mitigation of propagated delays via schedule buffers: Theory and empirics. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Trans- Portation Review, 150, 102333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2021.102333

Chandra, A., & Lederman, M. (2018). Revisiting the relationship between competition and price discrimination. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 10(2), 190–224. https://doi.org/10.1257/mic.20160

Chong, J. (2018). Airfares and ultra-low cost carriers in Canada. Canadian Library of Parliament Publication No. 2018–27-E. https://lop.parl.ca/sites/PublicWebsite/default/en CA/ResearchPublicat

Cook, G. N. & Goodwin, J. (2008). Airline networks: a comparison of hub-and-spoke and point-to-point systems. The Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education and Research, 17(2), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.15394/jaaer.2008.1443

Correia, S. (2016). A feasible estimator for linear models with multi-way fixed effects. Working paper. http://scorreia.com/research/hdfe.pdf.

Dai, M., Liu, Q., & Serfes, K. (2014). Is the effect of competition on price dispersion non-monotonic? Evidence from the US Airline Industry. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(1), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1162/RESTa00362

Escobari, D., Rupp, N., & Meskey, J. (2019). An analysis of dynamic price discrimination in airlines. Southern Economic Journal, 85(3), 639–662. https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12309

Forbes, S. J., & Lederman, M. (2009). Adaptation and Vertical Integration in the Airline Industry. American Economic Revie, w, 99(5), 1831–1849. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.5.1831

Gaggero, A. A., & Luttmann, A. (2023). The determinants of hidden-city ticketing: Competition, hub-and-spoke networks, and advance-purchase requirements. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 173, 103086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2023.103086

Gerardi, K. S., & Shapiro, A. H. (2009). Does competition reduce price dispersion? New evidence from the airline industry. Journal of Political Economy, 117(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1086/597328

Goolsbee, A., & Syverson, C. (2008). How do incumbents respond to the threat of entry? Evidence from the major airlines. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(4), 1611–1633. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.4.1611

He, L., & Kosmopoulou, G. (2021). Subcontracting Network Formation among US Airline Carriers. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 69(4), 817–853. https://doi.org/10.1111/joie.12273

He, L., Kim, M., & Liu, Q. (2022). Competitive response to unbundled services: An empirical look at Spirit Airlines. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 31(1), 115–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.124

Kwoka, J., Hearle, K., & Alepin, P. (2016). From the fringe to the forefront: low cost carriers and airline price determination. Review of Industrial Organization, 48(3), 247–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-016-9506-3

Lewis, M. S. (2021). Identifying airline price discrimination and the effect of competition. Interna- Tional Journal of Industrial Organization, 78, 102761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2021.102761

Luttmann, A. (2019). Evidence of directional price discrimination in the U.S. Airline Industry. In- Ternational Journal of Industrial Organization, 62, 291–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2018.03.013

Morrison, S. A. (2001). Actual, Adjacent, and Potential Competition: Estimating the Full Effect of Southwest Airlines. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 35(2), 239–256.

Shrago, B. (2022). The spatial effects of entry on airfares in the US Airline Industry. Economics of Transportation, 30(2022), 100251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecotra.2022.100251

Stigler, G. (1987). The Theory of Price (4th ed.). Macmillan.

Stole, L. A. (2007). Price Discrimination and Competition. In M. Armstrong & R. Porter (Eds.) Handbook of Industrial Organization: Volume 3 (pp. 2221–2299). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-448X(06)03034–2

U.S. Department of Justice. (2023, March 7). Justice Department Sues to Block JetBlue’s Proposed Acquisition of Spirit, Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice- department-sues-block-jetblue-s-proposed-acquisition-spirit

Varian, H. L. (1989). Price Discrimination. In R. Schmalensee & R. Willig (Eds.) Handbook of Industrial Organization: Volume 1 (pp. 597–654). North-Holland. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-448X(89)01013–7

Zou, L., Yu, C., Rhoades, D., & Waguespack, B. (2017). The pricing responses of non-bag fee airlines to the use of bag fees in the US air travel market. Journal of Air Transport Management, 65, 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2017.06.015

Acknowledgements

The research and views that are expressed herein do not necessarily constitute the views of the US Department of Transportation or the Office of Inspector General. I thank Jerrod Sharpe, Betty Krier, Eddie Watkins, Fernando Rios-Avila, and Volodymyr Bilotkach for their helpful suggestions, as well as the editor and two anonymous referees for their comments on an earlier draft of this paper. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shrago, B. The Spirit Effect: Ultra-Low Cost Carriers and Fare Dispersion in the U.S. Airline Industry. Rev Ind Organ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-024-09948-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-024-09948-y