Abstract

The Directorate General for Competition at the European Commission enforces competition law in the areas of antitrust, merger control, and State aid. After providing a general presentation of the role of the Chief Competition Economist’s team, this article surveys some of the main developments at the Directorate General for Competition over 2021/2022. In particular, the article reviews the new antitrust “Vertical Block Exemption Regulation” and “Vertical Guidelines”, the new “Guidelines on State aid for climate, environmental protection, and energy”, and the Veolia/Suez merger.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 1. Introduction: The CET in 2021-2022

The Chief Competition Economist’s team (CET) is a group of about 30 economists who provide advice to the Commissioner (Executive Vice-President Margrethe Vestager) and to the Director General (Olivier Guersent) of DG Competition. This advice concerns ongoing cases, revisions of practices and guidelines, as well as broader policy issues (e.g., green policies, industrial policies, digital sector regulation).

The CET does not just express an opinion on cases. Often some of its members are embedded in the case teams. This is generally the rule for mergers and has become much more common in antitrust and State aid—especially on the most relevant and complex cases. In addition, given the sheer number of State aid cases, the CET’s involvement in some of these cases is limited to performing specialised tasks and to vouching for the economic coherence of the analysis.

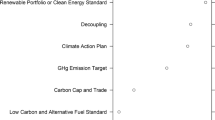

The Fig. 1 below describes the allocation of resources across tasks over the last few years.

Overall, while merger control used to account for a large part of our time, the dedication of resources has been increasingly more balanced. Recently, a similar amount of resources have been devoted to antitrust, merger control, and State aid control.

In the following sections, we summarize some of the main developments in our work over the last year: In antitrust, we outline the main changes in the new version of the Vertical Block Exemption Regulation (VBER) and the corresponding Vertical Guidelines. (Sect. 2). While it was a very busy year for State aid, we feel that the regulation of State aid that aims at achieving environmental objectives is worth special attention. Accordingly, with respect to the “Green Deal”, we discuss the new “Guidelines on State aid for climate, environmental protection, and energy” (CEEAG) (Sect. 3). Finally, Sect. 4 is devoted to a merger review—the Veolia/Suez case—where a catchment area analysis contributed to the assessment of the impact of the merger on local markets and bidding data were used to assess the closeness of competition between the merging parties and other suppliers.

2 2. Antitrust

2.1 Introduction

Between January 2021 and October 2022, the Commission took several interesting decisions in the antitrust area (outside cartels and merger control). We have already reported about the Aspen and Video Games cases in last year’s agency update (see Baltzopoulos et al., 2021).Footnote 1

In addition, in Insurance Ireland, the Commission concluded that Insurance Ireland had breached EU antitrust rules by restricting competition in the Irish motor vehicle insurance market.Footnote 2 The Commission considered that Insurance Ireland arbitrarily delayed—or in practice denied—access to its Insurance Link information exchange system, which contains information that is important in order to be active in the motor vehicle insurance market in Ireland. The Commission considered that restricted access to Insurance Link placed rival companies at a competitive disadvantage in comparison to incumbent companies that had access to the information exchange. This acted as a barrier to entry that reduced the possibility of more competitive prices and a greater choice of suppliers for consumers who seek motor vehicle insurance.

In Czech Network Sharing, the Commission was concerned that a network-sharing agreement among several mobile telecommunications operators in the Czech Republic was designed in a way that would reduce infrastructure competition between themFootnote 3: E.g., unilateral deployments and upgrades were charged by one party to the other in a way that reduced operators' individual incentives to invest. Moreover, the scope of the information that was exchanged among the parties went beyond what was necessary and included information that reduced the companies' incentives to compete. The parties remedied these issues through a broad set of commitments that addressed the Commission’s concerns.

There were also many interesting developments on the policy front: The Commission adopted a new Vertical Block Exemption Regulation (VBER) that was accompanied by new Vertical Guidelines, which will be discussed in detail below.Footnote 4 Moreover, the Commission published the draft for a revised Horizontal Block Exemption Regulation (HBER) accompanied by draft Horizontal Guidelines for public consultation.Footnote 5 The Commission also adopted Guidelines on collective agreements by solo self-employed people and a revised Informal Guidance Notice.Footnote 6 Moreover, the Commission launched a public consultation and evaluation of Regulation 1/2003 (the procedural framework that underpins the enforcement of EU antitrust rules).Footnote 7 Finally, the Digital Markets Act (DMA) was adopted.Footnote 8

There were also a significant number of important court judgments by the Court of Justice of the European Union in the antitrust area. In Intel (a referral back from the Court of Justice), the General Court found that the Commission’s original decision against Intel had not proven to the requisite legal standard that its loyalty rebates were likely to generate anticompetitive effects.Footnote 9 This case is now on appeal at the Court of Justice again, as it concerns important questions with regard to the standard of proof in unilateral conduct cases—including the use of economic evidence.

Also in Qualcomm Exclusivity, the General Court annulled a prior Commission decision about an alleged abuse of dominance.Footnote 10 The decision was overturned both for procedural and substantive reasons—notably due to a failure to take into account all of the relevant factual circumstances in the Commission’s analysis of whether the payments were capable of having anticompetitive effects.Footnote 11

On the other hand, the Commission prevailed in Google Shopping, where the General Court largely confirmed the Commission’s earlier decision.Footnote 12 The Commission had argued that Google had engaged in self-preferencing of its own comparison shopping service over competing services.Footnote 13 The Commission also prevailed in Google Android, where the General Court also largely confirmed the Commission’s earlier decision.Footnote 14 In that case, the Commission had argued that Google had imposed unlawful restrictions on manufacturers of Android mobile devices and mobile network operators so as to consolidate the dominant position of its search engine.Footnote 15

2.2 The Vertical Block Exemption Regulation and Vertical Guidelines

On 10 May 2022, the Commission adopted a new Vertical Block Exemption Regulation (VBER)Footnote 16 and new Guidelines on vertical restraints (VGL).Footnote 17The VBER, which entered into force on 1 June 2022, and the VGL replaced their respective previous versions of 2010. The adoption concluded an extensive review process, which began in October 2018. The new VBER and VGL will remain in force for a period of 12 years.

The rationale for the VBER and its structure remain generally unchanged: In contrast to restrictions in horizontal agreements between undertakings, restrictions in agreements between undertakings that are in a vertical relationship with one another—in particular restrictions in contracts between a supplier of goods or services and a buyer of such goods or services—are likely to lead to efficiencies that generally outweigh the possible negative effects of the restrictions on competition. For example, when a supplier restricts competition between its distributors in order to prevent them from free riding on each other’s sales efforts, this restriction may have an overall pro-competitive effect, as it may incentivise the distributors to invest more in sales efforts—such as pre-sales advice, customer service etc.

The VBER creates a safe harbour for vertical agreements by companies without market power. It does so by exempting certain agreements between undertakings from the application of Art 101(1) TFEU (VBER Art 2). This provides legal certainty to undertakings with regard to the legality of their vertical agreements—without the need for a detailed case-specific assessment. However, this exemption is subject to important conditions:

First, the VBER applies only where each of the undertakings that are party to the agreement has a market share not exceeding 30% of the relevant market: on the supply side and on the demand side of the market for the contracted goods or services (VBER Art 3).Footnote 18 Hence, the VBER does not apply to the agreements of undertakings with significant market power.

Second, vertical agreements that contain restrictions that are considered to have a particularly severe impact on competition—“hardcore restrictions”—fall outside of the block exemption in their entirety (VBER Art 4). The Commission applies a rebuttable presumption that such agreements are unlikely to give rise to efficiencies that fulfil the conditions of the exception provided by Art 101(3) TFEU.

Third, when vertical agreements include any of the “excluded restrictions” set out in VBER Art 5, only the restraint in question falls outside the safe harbourFootnote 19 and has to be assessed individually, with no presumption as to whether or not the restraint restricts competition within the meaning of Art 101(1) or fulfils the conditions of Art 101(3) TFEU.

Finally, the Commission or the competition authorities of the Member States may withdraw the benefit of the VBER in individual cases where they find that one or more of the conditions of Art 101(3) are not met (VBER Art 6).

The VGL provide detailed guidance on the application of the VBER and on the assessment of vertical restraints in individual cases that are outside the scope of the VBER.

By design, the VBER and VGL have a limited duration and hence need to be reviewed periodically. The objectives of the latest review were to: (i) adjust the safe harbour in order to eliminate false positives and false negatives under the previous VBER, as identified via enforcement experience and through several stakeholder consultations; (ii) provide up-to-date rules and guidance to help businesses self-assess the compliance of their vertical agreements with Article 101 TFEU; and (iii) ensure a harmonised application of the antitrust rules that relate to vertical agreements across the EU, as well as to simplify and improve the clarity of the rules and guidance.

Based on developments in the case law, case practice, and feedback from stakeholders, the new VBER contains several important changes: For example, changes to the rules on exclusive and selective distribution—as well as more detailed guidance on when online sales amount to active or passive selling—address “false negatives”.Footnote 20 This gives firms greater flexibility in the design of their distribution systems and their use of vertical restraints to achieve efficiencies, without the need for a case-by-case assessment.

Specifically, in the context of exclusive distribution systems,Footnote 21 the VBER now allows the supplier to appoint up to five distributors for each exclusive territory/customer group and to require its buyers to pass on the restriction of active sales to their immediate customers. With regard to selective distribution systems,Footnote 22 the supplier may now restrict all of its buyers—including those located outside the territory in which the selective distribution system is operated—from reselling the contract goods or services to unauthorised resellers that are located in that territory.

An example of changes that are aimed at eliminating “false positives”Footnote 23 concerns dual distribution, where a supplier sells to end customers both directly and through independent distributors. Evidence that was collected during the review process indicated that dual distribution has become more prevalent and may raise horizontal concerns—in particular related to information exchange. Therefore, while the dual distribution exemption is maintained and even extended to cover more levels of the supply chain, information exchange in dual distribution is exempted only where it is: (i) directly related to the implementation of the vertical agreement; and (ii) necessary to improve the production or distribution of the contract goods or services.

Perhaps the most notable changes of approach are linked to the significant growth in e-commerce over the last decade and to the emergence or growth of new players, such as online platforms. At the time of the last review in 2010, online sales were less prevalent than they are today. The policy approach that was taken at the time was therefore aimed at supporting the growth of the online channel, which was expected to bring benefits to consumers and promote market integration. The previous VBER and VGL hence took a strict approach towards restrictions of online sales. For example, under the previous VBER, essentially all online sales were considered “passive sales”Footnote 24 with the result that restrictions of such sales were generally considered as hardcore restrictions.

Today, online sales have evolved into a well-functioning sales channel that no longer needs special protection relative to offline sales channels. Quite the opposite: The decline of traditional high street stores—and physical stores more generally—is now a greater concern. The Covid-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the shift from offline to online sales. As a result, the policy focus has now shifted from a need to promote online sales to a need to maintain an effective balance between online sales and offline sales through brick-and-mortar stores. Moreover, the growth of large online platforms has increased concerns about the exercise of market power by such platforms.

The remainder of this section therefore focuses on changes in the new VBER and VGL in three important areas that relate to e-commerce: the assessment of online sales restrictions; the approach towards online platforms; and the treatment of parity clauses.

2.2.1 Assessment of Online Sales Restrictions

Under the new VBER, online sales restrictions that have as their object “the prevention of the effective use of the internet” (VBER Art 4(e)) constitute hardcore restrictions. As set out in the VGL, this will generally be the case for restrictions that: (i) require sales to be made only in a physical store; (ii) ban the use of the supplier’s brand on the distributor’s website; (iii) require the buyer to block website access to customers located outside the buyer’s territory or to re-route them; (iv) require the buyer to reject payments that are made with the use of foreign credit cards; (v) require the buyer to make a certain share of its total sales offline; or (vi) ban the use of entire online advertising channels: e.g., price-comparison websites or search engine advertising.

By contrast, restrictions of online sales that fall short of a prevention of the effective use of the internet remain block-exempted. This includes, for example, restrictions that impose: (i) quality requirements; (ii) marketplace bans; (iii) restrictions on online advertising, including restrictions on the use of particular providers (except where the restriction amounts to a de facto ban on the use of the entire advertising channel); (iv) a requirement to operate an offline store; or (v) a minimum absolute volume of offline sales.

This general framework applies irrespective of the type of distribution system that is operated by the supplier. Moreover, agreements must be assessed as a whole, as the combined use of several online sales restrictions—which individually may not prevent the effective use of the internet—may de facto achieve that result and hence amount to a hardcore restriction when they are used together. The VGL contain extensive guidance with regard to the application of this framework—in particular as regards the assessment of restrictions on the use of online marketplaces and price comparison websites (VGL Sects. 8.2.3 and 8.2.4).

Beyond this general framework, and in light of the development of online sales, the approach towards a number of specific online sales restrictions has also been relaxed: In particular, a supplier may now, within the safe harbour, charge different wholesale prices to the same buyer depending on whether goods are to be sold online or offline—provided that such “dual pricing” does not have the object of preventing the effective use of the internet or restricting sales to particular territories or customers. Similarly, where a supplier operates a selective distribution system, the criteria that it imposes with respect to online sales no longer need to be “equivalent” to those that it imposes for offline sales—provided again, that the criteria do not indirectly have the object of preventing the effective use of the internet.

Moreover, in the context of exclusive distribution, certain online sales are now considered “active sales” into an exclusive territory, and hence can be subject to restrictions: for example, if they originate from a website with a domain extension that is linked to the exclusive territory of another distributor, or if the website is in a language other than those commonly used in the distributor’s own territory.Footnote 25

Compared to the previous VBER, these changes allow suppliers greater flexibility to apply restrictions of online sales, while still providing limiting principles that indicate when such restrictions will amount to hardcore restrictions.

2.2.2 Treatment of Online Platforms

Although the intermediation of sales through platforms is not a new phenomenon, the rapid growth of online platforms—such as online marketplaces or price comparison websites—over the past decade has raised the question of how the rules on vertical agreements should be applied to intermediation services that take place in an online context, and whether online platforms need to be subject to a specific set of rules.

To tackle this issue, the VBER relies on the notion of “online intermediation services” (OIS), which are defined as information society services that facilitate direct transactions between undertakings that rely on such services or between such undertakings and final consumers (VBER Art 1(1)(e)).Footnote 26

The direct consequence of falling within this OIS definition is that the platform will be categorised as a supplier of such OIS services and not as a buyer of the products that it intermediates. Whether or not the platform falls within the VBER’s market share threshold hence depends on the market share that is held by the platform in the relevant market for the provision of OIS—and not in the market for the intermediated goods or services. Another important consequence is that the VBER’s list of hardcore restrictions applies to restrictions that are imposed by the platform on buyers of its OIS—the sellers that use the platform to sell their products; but the hardcore list does not apply to restrictions that are imposed on the platform by those undertakings.

For example, pursuant to Article 4(a) of the VBER, the safe harbour will not apply to an agreement under which a provider of OIS imposes a fixed or minimum sale price for a transaction that it facilitates. By contrast, restrictions that are imposed on a provider of OIS by buyers of the online intermediation services that relate to the price at which, the territories to which, or the customers to whom the intermediated products may be sold are block-exempted—since the provider of OIS does not buy or sell the intermediated products.

For many platforms—including marketplaces and price comparison websites—this increases legal certainty as to how the rules of the VBER apply to their agreements. Platforms that do not meet the new OIS definition may be categorised as suppliers or buyers—depending on the particular facts of the case—as under the previous VBER.

Another prevalent feature of many online platforms is that they also sell goods and services via the platform on their own behalf: “hybrid platforms”. In view of the competitive relationship between such hybrid platforms and the sellers that use them, the relative lack of enforcement experience more generally in relation to such hybrid platforms, and the fact that the Commission is only empowered to block-exempt agreements for which it has sufficient certainty that they generally meet the conditions of Article 101(3) TFEU, the Commission exercised a policy choice to exclude certain hybrid platform agreements from the safe harbour (VBER Art 2(6)).

For the individual assessment of such platform agreements outside the VBER, any vertical restraints will be assessed using the approach that is set out in the VGL, while horizontal aspects—including possible collusive effects—will be assessed under the guidelines on horizontal co-operation agreements.Footnote 27 At the same time, the VGL provide comfort to smaller hybrid platforms by making clear that their agreements will not be an enforcement priority if they do not contain by object restrictionsFootnote 28 and if the platform does not hold market power. This approach preserves resources for the scrutiny of agreements that are concluded by larger hybrid platforms while not hindering the emergence and growth of smaller platforms via a “hybrid platform” business model.

2.2.3 Parity Clauses

Another particularly hotly debated issue in recent years has been the use of parity clauses by online platforms. Such clauses typically take the form of platforms obliging sellers that rely on their OIS to not sell their goods or services at a lower price or better conditions: (i) via the seller’s own direct channels, such as their own website (“narrow” parity clauses); and/or (ii) via other indirect channels, such as other online platforms (“across-platform” parity clauses).

In the previous VBER, all parity clauses fell within the safe harbour of the VBER (subject to the market-share thresholds). This included “retail parity clauses”: parity clauses that relate to the conditions under which goods/services can be sold to final consumers, as well as parity clauses that relate to sales between professional suppliers and buyers: e.g., “most-favoured customer” (MFC) clauses. At the same time, recent enforcement experience—in particular, cases by EU National Competition Authorities in which the VBER market share thresholds were exceeded, namely in the hotel booking sectorFootnote 29 —indicates that retail parity clauses cannot be assumed to generally meet the conditions of Article 101(3) TFEU. There is also a growing economic literature which emphasizes that (retail) parity clauses can have pro- as well as anti-competitive effects.

Unfortunately, the economic literature and case experience to date remains relatively thin and typically deals only with the use of retail parity clauses by relatively large platforms: cases that do not fall under the VBER due to the market share thresholds.

The economic effects of retail parity clauses are likely to depend on many factors, including, for example: the intensity of competition between platforms; the importance of the direct and indirect sales channels; the degree of free riding across channels; consumer search patterns; whether sellers are able to refuse parity clauses; whether sellers need to be present on all platforms; etc. However, the specific mechanisms and conditions under which retail parity clauses are likely to lead to pro- or anti-competitive effects are not yet sufficiently well understood. It is hence difficult to draw general conclusions with regard to the effects of retail parity clauses. More research and case experience is needed.

The above considerations are reflected in the changes that were made in the new VBER with respect to retail parity clauses:

First, across-platform retail parity clauses are now classified as excluded restrictions (VBER Art. 5), with the consequence that this type of parity clause (or measures that achieve the same result) will be subject to an individual assessment. This reflects the concern that across-platform parity clauses tend to eliminate the incentives for platforms to compete on the commissions or fees that they charge for their OIS, because reducing the commission rate is not attractive for the platform unless it results in lower retail prices for the goods or services that are offered via the platform relative to the prices that are offered via rival platforms. In this sense, across-platform retail parity clauses are more severe restrictions than are narrow retail parity clauses.

Second, all other types of parity clause—including narrow retail parity clauses and non-retail parity clauses—remain block-exempted, which ensures continuity in this regard with the previous VBER. One reason for maintaining the block exemption for narrow retail parity clauses is that the risk of free riding on a platform’s investments via the direct channel appears greater than free riding between platforms, because consumer search costs for the direct channel are generally low and because suppliers do not need to pay OIS fees for sales on the direct channel.

Third, as the conditions under which the use of narrow retail parity obligations by multiple platforms will lead to negative cumulative effects are not yet well understood, the VBER (Art 6(1)) and VGL explicitly warn that the benefit of the block exemption may be withdrawn in individual cases in concentrated platform markets where several platforms use narrow retail parity obligations.

Overall, the approach to retail parity clauses strikes a reasonable balance between continuity and avoiding the risk of exempting anti-competitive agreements.

3 State Aid control

3.1 Introduction

Between January 2021 and July 2022, the Commission continue to adopt a very large number of decisions in the area of State aid control. Most of those decisions concluded that the actions were compatible with the Commission’s criteria for justifiable actions or did not actually involve aid.

During this period, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic continued to be significant. Individual cases and schemes have been approved under the “temporary framework” (TF) that was adopted in March 2020 and amended several times thereafter. In addition, as part of the EU response to the crisis and its evolution, the “recovery and resilience facility” (RRF) for all Member States has been approved and its implementation has started, which has led to an increasing number of State aid cases that are financed through RRF funds. The CET has been closely involved in the assessment of TF and RRF cases.

The aviation sector has been particularly affected since the onset of the Covid crisis. During this period the CET has contributed significantly to a number of cases in the field. Such cases have been under: the TF (e.g., Air France, Berlin airport); Article 107(2)(b) TFEU (damage compensation); the rescue and restructuring guidelines (such as TAP); or the market conform assessment of the establishment of the new company of ITA.

In response to the Russian military aggression to Ukraine, the Commission adopted a “temporary crisis framework” (TCF), which includes in particular measures for: liquidity support; solvency support; as well as support for continued production by firms that are exposed to large increases in energy costs. The CET has been closely involved in the design and application of the TCF.

In parallel to the numerous cases and policy initiatives related to the Covid crisis and to the Ukraine crisis, there has also been significant work on State aid guidelines. The Commission finalised and adopted the new “climate, environmental, and energy aid guidelines” (CEEAG) in January 2022 (which will be discussed in more detail in the remainder of this Section). The Commission’s work on the CEEAG has been in parallel with the continuous extensive work on schemes and individual cases in the energy sector—especially to support investment in renewable energy sources and improved energy efficiency.

Revised guidelines on State aid that promote risk finance investments, “important projects of common European interest” (IPCEI), and regional aid have also been adopted.

The Commission has continued working on the assessment of IPCEI—in particular on the development and adoption of hydrogen-based technologies. The CET has contributed to the assessment of these projects, especially by: identifying market failures that require State aid; reviewing the funding gaps of the projects; and assessing potential distortions of competition.

Securing supply chains is a priority on the agenda of the Commission. One such important area concerns the Commission proposal of the EU Chips Act in February 2022. The CET has been working on the framework of assessment of open strategic autonomy under State aid rules and has been contributing to specific cases in the field of semiconductors.

3.2 The European “Green Deal”

Climate change and environmental degradation pose an existential threat to the European and global economy. To overcome these challenges, the EU has launched a wide-ranging set of policies to make the EU’s economy more resource-efficient; the goal is for no net emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050 and the development of a strategy for economic growth that is decoupled from ever-increasing resource use.

The European Climate LawFootnote 30 also sets the intermediate target of reducing net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels. Climate neutrality by 2050 means achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions for EU countries as a whole, mainly by: cutting emissions; investing in green technologies; and protecting the natural environment. The law aims to ensure that all EU policies contribute to this goal and that all sectors of the economy and society play their part.

The EU Institutions and Member States are bound to take the necessary measures at EU and national level to meet the targets, taking into account the importance of promoting fairness and solidarity among Member States. Key areas of intervention include:

-

Cleaning the energy system by significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions: requiring higher shares of renewable energy and greater energy efficiency.

-

Decarbonising the industrial base by adopting cleaner technologies and products, particularly in certain sectors, including: energy, transport, construction, and energy-intensive users.

-

Transitioning towards greener mobility, promoting the growth of the market for zero- and low-emissions vehicles and extending carbon pricing to road, air, and maritime transport.

-

Improving the energy efficiency of buildings: both residential and commercial.

3.3 The rationale for State Aid

Achieving these ambitious targets will require: significant behavioural changes; transformation of many economic activities to meet new standards; and significant investment in innovation, technology adoption, adaptation of industrial processes and products, as well as the training of workforces. Markets are unlikely to trigger the necessary changes and deliver efficient outcomes in a timely manner by themselves due to the various market failures related to climate and environmental protection:

-

Negative externalities arise when pollution is not adequately priced. Firms acting in their own private interest may therefore have insufficient incentives to take the negative externalities that arise from their economic activity into account—either when they choose a particular technology or when they decide on their output level.

-

Positive externalities may occur, for instance, in the case of investments in eco-innovation, system stability, new and innovative renewable technologies, and innovative demand-response measures or—in the case of energy infrastructures or security of electricity supply—measures that benefit a wider number of firms and consumers.

-

Asymmetric information can exist in relation to the likely returns and risks of climate and environmental projects. The current context of rapid technological and regulatory change creates uncertainty that may be distinctly perceived by different market players, which exacerbates the problem of asymmetric information. For instance, entrepreneurs, investors and lenders may have different access and ability to assess information with regard to the long-term prospects of investments in nascent technologies.

-

Coordination failures may prevent the development of a project or its effective design due to: diverging interests and incentives among investors (“split incentives”; the costs of contracting or of liability insurance arrangements; uncertainty about the collaborative outcome; and network effects. Coordination failures may also stem from the need to reach a certain critical mass before it is commercially attractive to start a project—which may be a particularly relevant aspect in (cross-border) infrastructure projects.

In the presence of such climate and environmental market failures, public intervention may improve the efficiency of market outcomes through: regulation, for instance establishing stricter standards; taxation, for instance by increasing its private cost for polluters; as well as subsidies that incentivise more environmentally sustainable conducts.

Given the various forms of public intervention to address climate and environmental market failures, it is important that their design take into account the interaction and coherence between the various coexisting interventions. This is particularly relevant in relation to the EU emissions trading system (ETS), which is the cornerstone of the EU’s policy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The ETS contributes to internalising the cost of carbon emissions according to the “polluter pays principle” by establishing a market for carbon emission rights.

While the system applies to a wide range of sectors and the overall quota of carbon emission rights has decreased progressively since its introduction in 2005, the system still does not cover many economic activities.Footnote 31 Certain polluters are exempted from carbon emission costs in the ETS, and certain electricity-intensive consumers are compensated for the higher cost of their electricity consumption due to the carbon emission costs of electricity generation. This means that while the ETS contributes to the internalisation of carbon emission costs by market participants to a significant extent, there remain significant unaddressed residual externalities.

Climate and environmental regulation, taxation, and State aid can therefore be seen as necessary complements to the ETS in correcting the climate and environmental market failures and achieving the decarbonisation targets that are set out in the European Green Deal.

3.4 New Guidelines on State Aid for Climate, Environmental Protection, and Energy (CEEAG)

State aid control in the climate, environmental, and energy fields aims precisely at ensuring that State aid measures are well-designed, in combination with coexisting climate and environmental regulations and policies, to address specific residual market failures and to enable competitive markets to produce more sustainable outcomes. The principles of necessity, incentive effect, proportionality, and avoidance of undue distortions to competition in the compatibility assessment of climate and environmental State aid are key—from an economic perspective—to ensure efficient intervention in the market.

In January 2022 the Commission formally adopted the new Guidelines on State aid for climate, environmental protection, and energy (CEEAG). The new rules adapt the core principles of State aid control to the specificities of climate, environmental, and energy State aid in the very challenging context that is defined by the European Green Deal. The new rules aim at providing an economic and legal framework so as to enable the necessary public support to reach the European Green Deal targets in a cost-effective manner that minimises distortions to competition.

The CEEAG set the general principles of assessment and include a broad section on aid for the reduction in greenhouse gases emissions, as well as specific sections on aid for energy efficiency buildings, clean mobility, infrastructure, circular economy, pollution reduction, and the protection and restoration of biodiversity, as well as measures to ensure the security of energy supply.

3.4.1 State Aid to Address Residual Market Failures

According to the CEEAG, State aid measures with a climate or environmental objective should address a well-defined objective in the form of a residual market failure that is not yet addressed by existing climate and environmental policy instruments.Footnote 32

For instance, one could envisage granting a subsidy to a firm conditional on the adoption of a production technology with lower carbon emissions. If the adoption of such a technology is efficient from a climate or environmental perspective—given the reduction in carbon emissions that it can deliver relative to its additional costs—one should assess whether the existing climate and environmental policy instruments in place do not provide sufficient incentives for the firm to adopt the technology without the need of State aid support. These existing instruments may for instance include the ETS,Footnote 33 which might not apply to the firm in question, or regulatory standards, which may fall short of what would be efficient to incentivise a climate or environmentally efficient behaviour from that firm.

In this example, the limits of existing climate and environmental policy instruments to trigger the efficient adoption of more sustainable technologies by the firm would leave a residual market failure unaddressed, which would justify the need for the State aid measure.

State aid should be used only if it is more likely to address efficiently the residual market failure than would alternative possible measures, such as climate and environmental standards or taxation.Footnote 34

On the one hand, climate and environmental State aid measures should comply to the extent possible with the ‘polluter pays’ principle, by which the social cost of negative climate and environmental externalities are internalised by the market participant whose behaviour generates the negative external effect.Footnote 35 On the other hand, even when State aid may be the most appropriate measure to address a residual market failure, the aid needs to take the most appropriate and least distortive form.Footnote 36 For instance, if an environmentally beneficial investment is not taking place because the uncertainties about its prospects make access to private financing difficult, providing a public guarantee on a private loan may be less costly and less distortive than a grant.

3.4.2 Incentivising Behavioural Change

A climate or environmental State aid measure needs to incentivise the firm that receives support to change its behaviour in a way that is more sustainable for climate or from an environmental perspectiveFootnote 37: The climate or environmental State aid measure has an incentive effect if it triggers a conduct with lower climate or environmental impact than the one that the firm would have pursued in the absence of State aid.

Establishing the incentive effect of a State aid measure requires establishing credible factual and counterfactual scenarios, which are based on reliable evidence.Footnote 38 While this does not necessarily entail a detailed quantification of the financial prospects in the factual and counterfactual scenarios, it does require establishing with sufficient certitude that the firms would likely act as described in the counterfactual scenario: complying with any climate and environmental regulations, but in the absence of the proposed State aid measure.

3.4.3 Achieving Climate Targets in a Cost-Effective Way

The comparison of the factual and counterfactual scenarios allows not just establishing whether the State aid measure actually incentivises a more sustainable conduct, but it also provides the starting point to quantify the minimum amount of State aid that is needed to trigger the change of conduct. This minimum necessary amount of State aid corresponds to the net extra cost to the firm of following the conduct in the factual scenario instead of the conduct in the counterfactual scenario. It is the “funding gap”: the difference between the net present values of the factual and counterfactual scenarios, excluding State aid, for the firm.Footnote 39

The funding gap is at the same time the minimum amount of State aid that is needed for the measure to have an incentive effect on the firm and the maximum amount of State aid that is proportionate to the attainment of the climate or environmental objective of the State aid measure. Any amount of State aid in excess of the funding gap would not be justified by the need to trigger the desired change in the firm’s conduct and therefore would entail a degree of overcompensation. Amounts of State aid that are significantly below the funding gap may call into question the incentive effect of the measure, which suggests either a possible overestimation of the funding gap or the need for additional subsequent financial support to complete the project in the factual scenario.

The direct assessment of a funding gap requires the identification of all relevant expected cash flows of the firm in the factual and counterfactual scenarios; hence this entails an economic and financial assessment that is based on detailed information and assumptions. The assumptions and parameters of the funding gap assessment normally include (amongst others): expected revenues and costs; capital expenditures; the expected economic life of relevant assets; the estimated weighted average cost of capital (WACC); and reasonable terminal values (for instance, based on Gordon growth model or other well-established asset valuation approaches). Importantly, whenever the projects relate to intermediate inputs of production processes, profit contributions may need to be allocated and synergies with complementary activities of the beneficiary may need to be incorporated into the analysis.

Ultimately, the exercise intends to provide reliable economic estimates of the net present values for the firm in the factual and counterfactual scenarios, so as to quantify the resulting funding gap.Footnote 40

Tendering, if properly designed to ensure effectively competitive bidding, provides a mechanism to reveal the funding gap of the marginal bidder and to select the firms that can more efficiently contribute to the attainment of the climate or environmental objective of the State aid measure, and thereby reduce the need for detailed information and assumptions ex ante. Therefore, whenever State aid is allocated through effectively competitive tenders, the CEEAG do not require a detailed direct assessment of the funding gap.Footnote 41

In such cases, the proportionality assessment focuses on the proper design of the tender and the economic context in which it will take place, so that effective competition in the tender will ensure that the State aid that is allocated is the minimum necessary, and thereby reveals the underlying funding gap of the beneficiaries.Footnote 42

With regard to the main design features of competitive tenders, the CEEAG prescribe that:

-

“the bidding process is competitive, namely: it is open, clear, transparent and non-discriminatory, based on objective criteria, defined ex ante in accordance with the objective of the measure and minimising the risk of strategic bidding”;

-

“the criteria are published sufficiently far in advance of the deadline for submitting applications to enable effective competition”;

-

“the budget or volume related to the bidding process is a binding constraint in that it can be expected that not all bidders will receive aid, the expected number of bidders is sufficient to ensure effective competition, and the design of undersubscribed bidding processes during the implementation of a scheme is corrected to restore effective competition in the subsequent bidding processes or, failing that, as soon as appropriate”;

-

“ex post adjustments to the bidding process outcome (such as subsequent negotiations on bid results or rationing) are avoided as they may undermine the efficiency of the process’s outcome”.

These general requirements attempt to identify the basic conditions that are required to ensure the competitiveness of a tender and, therefore, the presumed proportionality of its outcome. Starting from these necessary conditions, the tendering design of each State aid measure requires an individualised assessment that takes into account the economic context of implementation.

If a tender is not effectively competitive, it does not reveal the minimum amount of State aid that is required and consequently proportionality cannot be presumed. Administrative procedures that are structured formally as tenders—but that are not effectively competitive and do not lead to identifying the minimum State aid required—cannot be presumed to deliver proportional State aid.

This is particularly relevant, for instance, whenever the risks of undersubscription emerge. Tenders that are expected by bidders to be undersubscribed are not competitive. When bidders are able to anticipate that the volume tendered is unrealistically high and that all eligible bidders will be successful, then they have an incentive to align their bids at the maximum level accepted by the auctioneer—the price cap—instead of bidding competitively. Undersubscribed tenders then become merely a formal procedure for administrative pricing at the level of bid caps, and are no longer effectively competitive tenders.

This does not mean that a tender may not be occasionally undersubscribed and at the same time effectively competitive. To the extent that there is a significant degree of uncertainty about the effectively available supply at a given point in time, an occasionally undersubscribed tender may not require immediate corrective measures on its design. Corrections in the design are only needed when undersubscription is repeated or expected. Corrections may include, for instance, broadening the eligibility criteria to increase the potential number of bidders or adjusting tendered volumes downwards ex ante to reflect potential supply.

These considerations are particularly relevant in view of ensuring a cost-effective path towards decarbonisation. Undersubscription of tenders increase the cost of State aid measures in support of decarbonisation without increasing the actual volumes that are contracted. Often, undersubscription signals the existence of exogenous constraints on the supply side that limit participation to the tenders in the short term. A cost-effective path towards decarbonisation therefore may require a combination of short-term measures to unlock potential supply with an ambitious increase of tendered volumes in the mid and long term—all of this while preserving the tenders’ competitiveness along the way. The CEEAG build on all of these facts, and require the correction of tender design so as to restore effective competition as soon as possible when undersubscription is identified—while remaining flexible about the precise ways of ensuring the competitiveness of tenders.

Either through competitive tendering or by assessing directly the funding gap, the proportionality of climate and environmental State aid measures is key for ensuring their cost-effectiveness and the overall financial feasibility of climate and environmental State aid policies.

3.4.4 Using Technologies Efficiently and Avoiding Undue Distortions to Competition

Climate and environmental objectives can be reached efficiently only if two additional conditions are fulfilled: First, as is required in the CEEAG, possible interactions of a State aid measure with other instruments of climate and environmental policy that contribute to the same or related climate or environmental objective must be considered. This is especially important for interactions with the ETS. Second, one must avoid any unnecessary distortions to competition that—by undermining the efficient functioning of markets—would impair the efficacy of complementary climate and environmental policies.

The proportionality of the State aid, especially when achieved through competitive tendering, provides a good starting point for minimising distortions to competition as it leads to the selection of the most efficient contributors to the achievement of the climate or environmental objective, and minimises the amount of State aid that is disbursed. However, by its very nature, any State aid measure will generate or threaten to generate some distortions of competition as the aid reinforces the competitive position of the beneficiaries.Footnote 43

In essence, climate and environmental State aid interventions may also distort price signals and market structure, which will consolidate market power by incumbent firms and inefficiently alter the process of entry and exit into the market. These risks can be particularly relevant in energy and industrial sectors that: are large carbon emitters; will undergo radical processes of decarbonisation over the next years; are highly concentrated; and exhibit significant barriers to entry and exit. Risks of undesired distributive impacts in society and of subsidy races between Member States may also arise.

Ultimately, the compatibility of a climate or environmental State aid measure with the EU State aid rules will require a balancing of its net contribution to the climate or environmental objective pursued against the competition distortions and welfare losses it may simultaneously cause.

The CEEAG identify in a non-exhaustive way a number of possible distortions that would undermine competition and the efficiency of market outcomes:

-

Undermining market rewards to the most efficient, innovative producers as well as undermining incentives for the least efficient producers to improve, restructure, or exit the market. This may also result in inefficient barriers to the entry of more efficient or innovative potential competitors. In the long term, such distortions may stifle innovation, efficiency, and the adoption of cleaner technologies.Footnote 44

-

Strengthening or maintaining substantial market power of the beneficiary. Even where aid does not strengthen substantial market power directly, it may do so indirectly: by discouraging the expansion of existing competitors or inducing their exit or discouraging the entry of new competitors.Footnote 45

-

Affecting trade and location choice. Those distortions can arise across countries—either when undertakings compete across borders or when they consider different locations for investment. Aid that is aimed at preserving economic activity in one region or attracting it away from other regions within the internal market may displace activities or investments from one region into another without any positive net climate or environmental impact.Footnote 46

A way of mitigating the distortions to competition of a State aid measure is to ensure that all potential market participants that can contribute to the achievement of its climate or environmental objective compete on their relative merits to be selected for State aid support.Footnote 47 This principle has often been referred to as “technology neutrality” of State aid measures: The design of the measure should not be arbitrarily biased in favour of certain beneficiaries. For instance, in principle, tenders in support of decarbonisation of electricity generation should be open to all low-carbon generation technologies to ensure that more cost-efficient approaches would be selected.

However, technology neutrality does not mean negating objective differences across beneficiaries. For example, there are significant differences across electricity generation technologies in terms of costs, intermittency, or operating times. Even within the same technology, significant differences can exist depending on the location of the units, their size, or their access to the grid. These objective differences may justify technology specific designs or other restrictions in eligibility criteria.

The CEEAG acknowledge this and allow for decarbonisation State aid measures that target specific technologies and economic activities, if reasons that are based on objective considerations are provided—in particular related to efficiency and cost heterogeneity.Footnote 48

The choice between broader and narrower tender designs depends largely on informational asymmetries and uncertainties about the relative merits of various technologies. An auctioneer that has limited knowledge about the private characteristics of the various technologies—especially on current and future costs—may want to use a broader tender design so that the relative efficiency of the various bidders is revealed through their bids. The cost of learning from a broader tender takes the form of higher infra-marginal rents. The more accurate is the knowledge that the auctioneer has about the features of distinct technologies, the better positioned it is to design separate tenders that reflect their specific cost structure and reduce infra-marginal rents.

At the same time, by separating tenders the auctioneer sets the relative quantities to be procured of each technology, which may not be trivial from a dynamic perspective. As Fabra and Montero (forthcoming) put it, “the comparison of a technology neutral versus a technology specific approach is faced with a fundamental trade-off. By allowing quantities to adjust to cost shocks, the technology neutral approach achieves cost efficiency at the cost of leaving high rents with infra-marginal producers. In contrast, the technology specific approach sacrifices cost efficiency in order to reduce those rents. In doing so, it also exploits the benefits that accrue from the (possibly, imperfect) substitutability across technologies. Therefore, whether one approach dominates over the other depends on the specifics of each case.”

Hybrid approaches with minimum technology quotas can also be envisaged and may in certain circumstances offer a way out from this trade-off.

The neutrality of a tender also depends on the criteria to select the beneficiaries. While the amount of aid that is needed per unit of carbon emission abated should be a main decision factor, some of the other dimensions that were mentioned above might also be valuable to the auctioneer. The CEEAG allows such complementary criteria to be given some limited weight.Footnote 49 Importantly, all of these considerations about tender design are relevant for State aid and competition distortions to be the minimum that is necessary—as well as to ensure an efficient use of the available technologies.

3.4.5 Phasing Out Fossil Fuels

Decarbonising the economy will require not just significant investment in non-carbon-emitting technologies, but also the phasing-out of carbon-emitting ones. The CEEAG provide two complementary approaches to speed up this transition: limiting the granting of State aid to support new investment in fossil fuels, and allowing the granting of State aid to accelerate the decommissioning of fossil fuel plants.

The CEEAG consider that measures that incentivise new investments in energy or industrial production based on the most polluting fossil fuels—such as coal, diesel, lignite, oil, peat, and oil shale—increase the negative climate and environmental externalities in the market. They will not be considered to have any positive climate or environmental effect—given the incompatibility of these fuels with the climate targets.

Similarly, measures that incentivise new investments in energy or industrial production based on natural gas may reduce greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants in the short term but aggravate negative climate and environmental externalities in the longer term, compared to alternative investments. For investments in natural gas to be seen as having positive climate or environmental effects, Member States must explain how they will ensure that the investment contributes to achieving the Union’s 2030 climate target and 2050 climate neutrality target. In particular, the Member States must explain how a lock in of this gas-fired energy generation or gas-fired production equipment will be avoided.Footnote 50 This approach is consistent with the view of natural gas as a transitional source of energy in the context of the European Green Deal.

While the shift away from coal, peat, and oil shale activities is largely driven by regulation, market forces such as the effects of carbon prices and competition from renewable sources with lower costs can also be important. Member States may decide to accelerate this market-driven transition by prohibiting the generation of power that is based on these fuels as of a certain date. This prohibition can create situations in which profitable coal, peat, and oil shale activities have to close before the end of their economic lifetime and can hence result in forgone profit. Member States may wish to grant compensation to facilitate the green transition.Footnote 51

Moreover, the closure of uncompetitive coal, peat, and oil shale activities can generate significant social, climate, and environmental costs at the level of the power plants and the mining operations. Member States may decide to cover such exceptional costs to mitigate the social and regional consequences of the closure.Footnote 52

3.4.6 Preserving Industrial Competitiveness Through the Energy Transition

The European Green Deal requires that Member States put in place ambitious decarbonisation policies with budgets that will continue to be financed at least partly through levies on electricity consumption. For economic sectors that are particularly exposed to international trade and heavily reliant on electricity for their value creation, the obligation to pay the full amount of such levies can heighten the risk of moving to locations where climate and environmental policies are absent or less ambitious. As decarbonisation is a worldwide concern, such relocation would entail both a loss of local employment and a worsening of global climate and environmental conditions. To mitigate those risks the CEEAG foresee the possibility of granting reductions from such levies for firms that could be particularly affected.Footnote 53

The basic limiting principle for the granting of reductions from levies is the “cost-reflectiveness principle”. Levies that reflect part of the cost of providing electricity expose final customers to the true costs of supplying the secure electricity that they consume, which contributes to efficient demand response. In order to preserve the cost reflectiveness of electricity bills, exemptions from network charges or from charges that finance capacity are not allowed. Member States may instead grant reductions from levies on electricity consumption that do not directly reflect part of the cost of providing secure electricity—such as levies that finance climate or environmental policy objectives or other social policy objectives.Footnote 54

The CEEAG limit the exemptions from levies on electricity consumption to firms that may be at risk of delocalisation—which is identified at the sectoral level, based on the electro-intensity of the sector and its openness to international trade.Footnote 55

3.4.7 Concluding Remarks: The Challenges Ahead

Since the adoption of the CEEAG in January 2022, energy markets have been affected by exceptional events: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; interruptions in gas supplies; and an escalation in energy prices. In response to these events, already in March 2022 the European Commission proposed the outline of a plan to make Europe independent from Russian fossil fuels before 2030 and adopted a Temporary Crisis Framework to enable Member States to use the flexibility that was foreseen under State aid rules to support the European economy. In May 2022 the European Commission presented the REPowerEU Plan in response to the hardships and global energy market disruption that were caused by Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

The Commission’s plan aims to reduce the EU's dependence on fossil fuels and to accelerate the energy transition that was already foreseen to attain the targets of the European Green Deal. The plan includes actions in five main areas:

-

Reducing energy consumption by enhancing long-term energy efficiency measures and triggering behavioural changes in energy consumption;

-

Diversifying supplies by securing higher levels of LNG imports, optimising infrastructure use, pooling demand, and supporting international suppliers;

-

Accelerating the rollout of renewables and the development of renewable hydrogen technologies and infrastructure;

-

Reducing fossil fuel consumption in industry and transport through energy savings, efficiency enhancement, fuel substitution, electrification, and an enhanced uptake of renewable hydrogen, biogas, and biomethane;

-

Enabling additional investment and reorienting the existing national Recovery and Resilience Plans to align them with the priorities in the REPowerEU plan.

The priorities and lines of action that were set out in the REPowerEU Plan will require an even greater effort in terms of public and private investments in line with the European Green Deal: The targets are more ambitious, and the timeline to achieve them is shorter.

In September 2022 the Commission proposed emergency interventions in Europe's energy markets to limit the impact of disruptions in gas supplies and increases in energy prices. These interventions included exceptional electricity demand reduction measures and measures to claw-back infra-marginal rents of electricity generation so as to redistribute them amongst consumers, as well as solidarity measures that tax the profits of oil and gas companies. These measures were added to previously agreed measures on filling gas storage and reducing gas demand in preparation for the upcoming winter. The Commission continues its work to improve liquidity for market operators, bring down the price of gas, and reform the electricity market design for the longer term.

A reflection was also launched by the Commission to study options to improve the long-term functioning of the electricity market. These include: market-based instruments to protect consumers against price volatility; measures to enhance demand-response and promote individual self-consumption schemes; appropriate investment signals; a more transparent market surveillance; and possible adjustments to the electricity market design.

While all of these elements depict a challenging context for the implementation of the CEEAG, their design responds precisely to the needs for State aid that are posed by the European Green Deal, and are reinforced by the current energy crisis. The CEEAG—together with the Temporary Crisis Framework—aim to provide the guidance to enable the necessary State aid support for the economy today and over the coming years.

4 Mergers

4.1 Main Developments

Between January 2021 and September 2022, 673 merger investigations were concluded at DG Competition. The vast majority (523 cases) were unconditional clearances under a simplified procedure. 13 cases were abandoned in phase I. Of the remaining cases, 122 were concluded during a (non‑simplified) phase I investigation and 15 were concluded during a phase II investigation.Footnote 56 Of the (non‑simplified) phase I cases, 110 were cleared unconditionally, and 12 could be cleared in phase I subject to commitments. The phase II investigations resulted in 6 clearances that were subject to commitments,Footnote 57 no unconditional clearance, 2 prohibitions,Footnote 58 and 6 abandoned transactions.Footnote 59 Therefore, 5.8% of cases were not cleared unconditionally during this period.

The CET was involved in all second‑phase investigations as well as in many complex first‑phase investigations. Analyses by members of the CET included, for instance: bidding analyses; quantitative market delineation (such as catchment-area analysis); as well as conceptual contributions to the construction and testing of sound theories of harm.

As was mentioned in last year’s RIO paper on DG Competition developments,Footnote 60 as a new policy initiative the Commission welcomes Member State referrals of mergers that are below the EU’s revenue thresholds with significant anti-competitive potential in the context of Article 22 of the Merger Regulation.Footnote 61 The first case that was investigated by the Commission in the context of this initiative was the Illumina/Grail merger.,Footnote 62Footnote 63 The case involved the vertical integration of Illumina—the unrivalled supplier of “next generation sequencing” (NGS) systems for genetic and genomic analysis—with GRAIL: a customer of Illumina that used NGS systems to develop cancer detection tests.

The Commission prohibited the merger as it would have stifled innovation, and reduced choice in the emerging market for blood-based early cancer detection tests through vertical foreclosure. Illumina has indicated that it will appeal the Commission’s decision.Footnote 64

4.2 Veolia/Suez Merger

On 14 December 2021, the Commission cleared a merger between Veolia and Suez, subject to conditions.Footnote 65 Veolia and Suez are leaders in the water treatment and waste management sectors, where the two companies offer a wide range of services to municipal and industrial customers, including in particular:

-

For the water sector: the provision of services that relate to the design and construction of water treatment facilities, the operation and maintenance of these water treatment facilities, the supply of water treatment chemicals, and the provision of mobile water solutions;

-

For the waste sector: the provision of services that relate to the collection and treatment of non-hazardous waste, regulated waste (such as electrical equipment, medical waste), and hazardous waste.Footnote 66

The Commission found that the Transaction, as initially notified, created significant horizontal overlaps and would lead to competition concerns in various markets, notably: (i) municipal water management in France; (ii) industrial water management in France; (iii) mobile water services in the EEA; (iv) the collection and treatment of non-hazardous and regulated waste in France; and (v) the treatment of hazardous waste in France.

With regard to water management, the Commission considered national markets: Market shares were particularly high in France, with a combined market share of the two merging companies of 80–90% for the production and distribution of municipal water; 70–80% for the collection and treatment of used water; and 50–60% for industrial water management.

With regard to waste management, the Commission found that the local dimension was an important element for the assessment of the proposed Transaction for non-hazardous waste, regulated waste, and hazardous waste in France:

-

For non-hazardous waste, the Commission assessed the market structure for each French department (including also neighbouring departments) where a treatment site of the merging parties was located.Footnote 67 We considered a catchment area of 200 km around each site for both the incineration of non-hazardous waste and the landfilling of non-hazardous waste.Footnote 68

-

For regulated waste, the Commission assessed the market structure at the regional level for the collection and the treatment of electrical equipment, at the departmental level and regional level for the treatment of medical waste, and at departmental level and regional level for the collection of furnishing waste.

-

For both the landfilling and incineration of hazardous waste, the Commission considered local markets with a 300 km catchment area around each site of the merging parties. In addition, the Commission also used a customer-centric approach, by assessing the accessibility of sites. This customer-centric approach complemented the site-centric approach and provided additional insights for the assessment of the proposed Transaction.

The CET was involved in the assessment of local markets, supporting the case for the catchment-area analyses that are more standard—centered on each site of the merging parties—and designing the customer-centric catchment areas analysis for hazardous waste (Sect. 4.2.1).

In the various markets for water management and waste management, customers typically select the services providers through tenders. The Commission relied on the analysis of tender data in its competitive assessment to measure the competitive interactions between the merging parties that would be lost post-Transaction (Sect. 4.2.2).

The next two sections focus on the main economic contributions to the case: (i) the catchment area analyses that were carried out for hazardous waste in France (Sect. 4.2.1); and (ii) the analysis of tender data (Sect. 4.2.2).

4.2.1 Site-Centric and Customer-Centric Catchment Area Analyses

4.2.1.1 Description of the available data and the different approaches for catchment-area analyses

The Commission identified competition concerns for the treatment of hazardous waste in France through landfilling and incineration.Footnote 69 The evidence indicated that clients have a strong preference for sending their dangerous waste over a relatively short distance.

In particular, the Commission analysed data on the volumes of dangerous waste that were collected by each site of the merging parties and their main competitors and calculated the distance that corresponded to 70% of the volume collected, as well as for 80% and for 90%.Footnote 70 The Commission considered that the distance that corresponded to the 80% volume-threshold was the most appropriate since it was also confirmed by feedback that was received from the market investigation; this threshold also removed volumes that were sent over longer distance due to exceptional circumstances, and made it possible to capture the competitive interactions between the merging parties and their competitors.

This led to catchment areas of 300 km radius for both the landfilling and the incineration of hazardous waste. In practice, a circle of 300 km radius is drawn around each site of the merging parties, and market shares are calculated by taking into consideration the total volume that is treated by each site included in the catchment area (see Fig. 2). Since data on the total volume that is treated by a site is generally available for both the merging parties and their competitors, the site-centric approach is relatively straightforward to implement.

In its assessment, the Commission also considered a catchment-area analysis that centered on customers and was based on the actual shipments of hazardous waste that were sent by customers to the sites of the different competitors.Footnote 71 The combination of the two approaches provided important insights for the design of the remedy in order for the merging parties to divest the appropriate sites to resolve competition concerns at a local level.

The customer-centric approach was possible in this case due to the quality of the data available. Calculating market shares around a specific customer (and based on actual shipments from this specific customer to the sites of the merging parties and their competitors) requires data on all waste flows that were received by each site of the merging parties and their competitors from this specific customer. This approach raises practical issues in terms of data, which explain why in practice this is less often used than is the site-centric approach:

-

First, this customer-centric approach requires data from the merging parties and their competitors on the waste that is sent by each of their customers to each of their sites. While it is generally feasible to obtain this (granular) data from the merging parties, getting such data from third-parties is more difficult as it involves significant work from third-parties.Footnote 72 Moreover, making data consistent across the merging parties and third-parties is also necessary to proceed with a market reconstruction: The main task is to calculate a reliable market size that captures all of the alternatives that are available for each specific customer. This data-management task is often very time-consuming: For example, for the incineration of hazardous waste in France, the Commission considered 11 competitors in the customer-centric analysis;

-

Second, while this approach is not too hard to implement with only a few customers, it quickly becomes impractical when customers become more numerous and more dispersed.

Fortunately in this case, the shipment of hazardous waste in France is regulated, and each shipment needs to be declared to the public administration. A database can therefore be made available with the customer names anonymisedFootnote 73:

-

As the French department where the customer is located is available in the database, it is possible to aggregate all customers at a department level. Since departments in France are sufficiently granular (see Figs. 3 and 4), this allows the pooling of customers that face similar competitive conditions.

-

For a specific department, the data identify the receiving site for each shipment. We can therefore construct waste flows for both the merging parties and the third-party competitors, which can be used to calculate market shares based on a market size that captures all alternatives that are available for customers that are located in a specific department.

4.2.1.2 The Catchment Area Analysis for the Landfilling of Dangerous Waste in France

The site-centric market shares for the landfilling of dangerous waste are reported in Table 1; these data show that the proposed Transaction would create:

-

A quasi-monopoly in the South of France, around a site of Suez (Bellegarde) with a combined share in the range of 90-100% and a site of Veolia (Occitanis) with a combined share in the range of 90-100%;

-

A quasi-monopoly in the East of France, with a significant increment around one particular site of Suez (Laimont) with a combined share of 90-100%;

-

A quasi-monopoly in the Paris area, with a combined market share in the range of 90-100% around a site of Veolia (Guitrancourt) and a site of Suez (Villeparisis);

-

A high combined market share in the North- of France, in the range of 60-70% around a site of Veolia (Solicendre).

However, in the West of France, the combined market share of the merged entity would be lower, in the range of 30–40% around a site of Suez (Champteussé-Sur-Baconne) and 20–30% around a site of Veolia (Solitop), with the presence of a strong competitor (Séché).

As was described above, for each flow of waste that is sent to a site in France, the data identify the department of origin of the customer that sent the waste for treatment. We can therefore adopt a customer-centric approach, where for each department, one can calculate the market shares of the merging parties and their competitors based on the actual volumes that were sent by customers. This approach has several advantages compared to a site-centric approach:

-

The market shares are based on the sites that are effectively used by the merging parties; and

-

The market shares do not depend on any specific radius since actual volumes are used.

Figure 3 reports, for each department in France, the combined market share of the merging parties and the increment.

This customer-centric analysis confirmed our previous findings as to the likely consequences of the merger based on site-centric market shares:

-

A quasi-monopoly in the South of France, with a significant increment above 10% in several departments (for example, Aude, Hérault, Haute-Garonne, Tarn-et-Garonne, Lot, Cantal), and even above 40% in three departments (Tarn, Aveyron, Gard);

-

A quasi-monopoly in the Paris area, with a significant increment in Paris area and in the North of France;

In addition, a customer-centric approach revealed additional evidence for the West of France, where customers used much more Suez (which owns one site in the West of France) compared to what was suggested by site-centric market shares (Table 1 above). In particular, the proposed Transaction led to a significant increment for several departments in the West of France (for example, above 20% in Gironde, Charente-Maritime, Deux-Sèvre, Vendée, Maine-et-Loire, Sarthe, and above 10% in Loire-Atlantique, Orne, Calvados, Manche).

4.2.1.3 The catchment area analysis for the incineration of dangerous waste in France

The corresponding market shares (site-centric approach) for the incineration of hazardous waste in France are reported in Table 2; these data show that the proposed Transaction would lead to combined market shares above 50% for seven of the eight Suez sites.

The customer-centric approach, which considers the sites that are effectively used by customers for the incineration of hazardous waste, also showed a high degree of competitive interactions between the sites of the merging parties. For each department, the Commission calculated the share of volume that was sent to each site of the suppliers that were active in the incineration of hazardous waste.Footnote 74 In order to identify the sites of the merging parties that compete against each other for the customers in a given department, Fig. 4 reports the combined market share of the merging parties and the increment.

The customer-centric approach showed that several sites of the merging parties were competing head-to-head:

-