Abstract

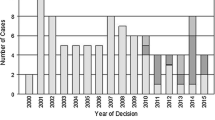

This paper provides a comprehensive and detailed quantitative characterisation of 118 detected cartels and the underlying enforcement process in South Africa for the period 1998 to 2019. The paper also employs survival analysis to investigate the effect of different cartel and enforcement characteristics on the probability of cartel breakdown. The analysis reveals that South African cartels are mostly similar to international cartels, with an average duration of 6.2 years, which is comparable to European and American cartels; however, South African cartels are on average smaller: They involve fewer participants. Furthermore, the data support a hypothesis of increased activity in the anti-cartel sphere over the sample period. We find that the corporate leniency policy has contributed to the prosecution of about 30% of the cartels that were prosecuted in our sample, while penalties are on average below 5% of total revenue—which is below the statutory limit of 10%. Moreover, the survival analysis suggests that the corporate leniency policy may have shortened the expected duration of detected cartels—at least when we consider cartels that came into existence after the introduction of the policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Groups of firms were formed according to their respective European Commission decisions: Firms within a group were linked through ownership and were jointly liable for cartel fines (Hellwig & Hüschelrath, 2017, p. 405)

The decisions are published on the Competition Tribunal website: www.comptrib.co.za

The earliest cartel start date in the dataset is 1973.

The grounds on which cases were contested vary. In some cases the respondents denied the allegations against them; in other instances the respondents challenged the facts of the case or sought a reduction to the penalty levied against them. These contested cases would in some instances result in cases being dismissed or a reduction of penalties.

The box shows the range for the middle 50% of duration values: from the 25th to the 75th percentile. The solid thick line inside the box shows the median. In addition, two horizontal lines at the top and bottom—called ’whiskers’—denote the maximum and minimum duration. Outlier values are denoted by small circles.

The sector categories are taken from the South African Revenue Services’ Industry classification codes (see Appendix A.12). While wholesale and retail trade are considered one category, we present the two groups separately.

PST activities, refers to Professional, scientific, and technical activities.

Other Industry refers to the following industries: Waste supply, waste management and remediation; Information and communication; Human health and social work activities; Financial service activities; Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply; Arts entertainment and recreation; Agriculture, forestry and fishing; and Administrative and support service activities

After the uncovering of widespread collusion in the construction industry, the Competition Commission decided in 2011 to invite all firms in the construction industry to apply for leniency in order to fast-track the process. (Case No: 017061, Competition Tribunal, In the matter between The Competition Commission and WBHO Construction (Pty) Ltd, 22 July 2013)

The drop in the 3-year moving average penalty in 2018 is mainly a result of small firms (in terms of revenue) being penalized in 2019, resulting in substantially smaller penalties. The data show that total penalties in 2019 were about R50 million, while the total penalties in 2017 and 2018 were R589 million and R613 million, respectively.

The remaining 15% is composed of: firms that were granted immunity (6.3%); firms on which no penalty was imposed (6%); firms whose cases were later dismissed (1.3%); and firms for which the reasons are unclear (1.4%)

For the remaining 123 firms that were penalized, there is no specification of the exact percentage of total revenue to which the penalty relates: It is stated that the penalty did not exceed 10% for 83 of the 123 firms, and no indication is provided for the remaining 40 firms.

The data in this sample include only non-censored cartel episodes, as the sample relates to prosecuted cartels that all have a start and end date. Censored cartel data would require an adjustment to the methodology

An index of the number of legal publications that mentioned the Corporate Leniency Program of any antitrust jurisdiction in the year that the cartel ended.

References

Bolotova, Y., Connor, J. M., & Miller, D. J. (2009). Factors influencing the magnitude of cartel overcharges: An empirical analysis of the U.S. Market. Journal of Competition Law and Economics, 5(2), 361–381.

Boshoff, W. H. (2015). Illegal cartel overcharges in markets with a legal cartel history: Bitumen prices in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics, 83(2), 220–239.

Boshoff, W. H., & van Jaarsveld, R. (2019). Recurrent collusion: Cartel episodes and overcharge in the South African cement market. Review of Industrial Organisation, 54(2), 353–380.

Boswijk, H. P., Bun, M. J. G., & Schinkel, M. P. (2019). Cartel dating. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 34(1), 26–42.

Brenner, S. (2009). An empirical study of the European corporate leniency program. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 27(6), 639–645.

Carree, M., Gunster, A., & Schinkel, M. P. (2010). European antitrust policy 1957–2004: An analysis of commission decisions. Review of Industrial Organization, 36(2), 97–131.

Combe, E., & Monnier, C. (2012). Les cartels en Europe, une aalyse empirique. Revue francaise d’economie, 27(2), 187–226.

Commission, Competition Tribunal. (2009). Unleashing rivalry—Ten years of enforcement by the South Africa competition authorities 1999–2009 . Pretoria. Retrieved from www.comptrib.co.za

Competition Commission of South Africa. (2008). Competition Commission of South Africa annual report: 2007/2008.

Competition Commission of South Africa. (2015). Guidelines for the determination of administrative penalties for prohibited practices.

Connor, J. M. (2003). Private international Cartels: Effectiveness, welfare, and anticartel enforcement. Staff Paper No 03-12 West Lafayette. In Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University.

Connor, J. M. (2006). Effectiveness of antitrust sanctions on modern international Cartels. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 6(3–4), 195–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-006-0028-9

Connor, J. M. (2011). Cartel fine severity and the European Commission . European Competition Law Review, 27(36).

De, O. (2010). Analysis of Cartel duration: Evidence from EC prosecuted cartels. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 11(1), 33–65.

Fourie, F. Cv. N. (1987). Issues and problems in South African competition policy. South African Journal of Economics, 55(4), 217–229.

Green, E. J., & Porter, R. H. (1984). Noncooperative collusion under imperfect price information. Econometrica, 52(1), 87.

Harrington, J. E., & Wei, Y. (2017). What can the duration of discovered cartels tell us about the duration of all cartels? The Economic Journal, 127(604), 1977–2005.

Hellwig, M., & Hüschelrath, K. (2017). Cartel cases and the cartel enforcement process in the European Union 2001–2015: A quantitative assessment. The Antitrust Bulletin, 62(2), 400–438.

Hellwig, M., & Hüschelrath, K. (2018). When do firms leave cartels? Determinants and the impact on cartel survival. International Review of Law and Economics, 54, 68–84.

Kleinbaum, D. G., & Klein, M. (2012). Survival analysis. In Statistics for biology and health. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6646-9.

Levenstein, M. C., & Suslow, V. Y. (2006a). Determinants of international cartel duration and the role of Cartel organization. University of Michigan Ross School of Business Working Paper Series, No. 1052.

Levenstein, M. C., & Suslow, V. Y. (2006b). What determines cartel success? Journal of Economic Literature, 44(1), 43–95.

Levenstein, M. C., & Suslow, V. Y. (2011). Breaking up is hard to do: Determinants of cartel duration. Journal of Law & Economics, 54(2), 455–492.

Lunn, M., & McNeil, D. (1995). Applying cox regression to competing risks. Biometrics, 51(2), 524–532.

Makhaya, G., Mkwananzi, W., & Roberts, S. (2012). How should young institutions approach competition enforcement? Reflections on South Africa’s experience. South African Journal of International Affairs, 19(1), 43–64.

Maphwanya, R. (2017). Cartel likelihood, duration and deterrence in South Africa. In: Competition law and economic regulation: Addressing market power in Southern Africa (pp. 49–70). Wits University Press.

Mncube, L. (2014). The South African wheat flour cartel: Overcharges at the mill. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 14(4), 487–509.

Motta, M. (2004). Competition policy: Theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Muzata, T., Roberts, S., & Vilakazi, T. (2017). Penalties and settlements for South African cartels: An economic review. In Competition law and economic regulation: Addressing market power in Southern Africa (pp. 13–48). Wits University Press.

Porter, R. H. (1983). A study of cartel stability: The joint executive committee, 1880–1886. The Bell Journal of Economics, 14(2), 15.

Posner, R. A. (1970). A statistical study of antitrust enforcement. The Journal of Law and Economics, 13, 367–419.

Roberts, S. (2004). The role for competition policy in economic development: The South African experience. Development Southern Africa, 21(1), 227–243.

Vanhaverbeke, L., & Buts, C. (2020). A quantitative analysis of the efficiency of the EU’s leniency policy. European Competition and Regulatory Law Review, 4(1), 12–22.

World Bank Group. (2016). South Africa economic update: Promoting faster growth and poverty alleviation through competition. World Bank Publisher.

Zimmerman, J. E., Connor, J. M. (2005). Determinants of cartel duration: A cross-sectional study of modern private international cartels. Available at SSRN 1158577.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nkosi, W.W., Boshoff, W.H. Characteristics of Prosecuted Cartels and Cartel Enforcement in South Africa. Rev Ind Organ 60, 327–360 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-022-09862-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-022-09862-1