Abstract

This paper uses firm-level data from company tax declarations to analyse the complementary relationship between direct access to imported intermediate inputs and manufacturing firm productivity in South Africa. We provide support for the hypothesis of firm learning by importing. Our results show that importing is associated with higher productivity among South African manufacturing firms. In addition, importing a wider variety of intermediate inputs is associated with higher firm productivity, which is consistent with the idea that imported input varieties complement domestic varieties in production. We do not find strong evidence that imports from advanced economies are more relevant for productivity than are imports from emerging economies—which is contrary to expectations that the superior technology that is embedded in advanced economy imports would boost firm productivity.

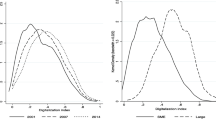

Source: Authors’ elaboration on SARS CIT and transaction trade data

Source: Authors’ elaboration on SARS CIT and transaction trade data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The South African government imposed quotas on imports of Chinese apparel in 2007 and 2008 in an attempt to curb job losses in the apparel industry. This was followed by increases in tariff rates on apparel imports to the WTO bound rate.

Some caution is required in interpreting the data on trade in value added, as the estimates are strongly influenced by the database that is used. Farole (2016) estimates a 14% share of foreign value added in South Africa’s gross exports with the use of the Eora GVC database (https://worldmrio.com/unctadgvc/), whereas the OECD (2018) estimates a much higher 21–24% share over the period 2011–2014 with the use of its Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database.

Such emphasis on the role of importing is not new. Endogenous growth models emphasize the static and dynamic gains from importing new varieties of inputs and show that these contribute to a country’s growth via gains in productivity and by fostering the development of new varieties of domestic products (Broda and Weinstein 2006; Goldberg et al. 2010).

Firms’ performance is measured in their study as the number of varieties of products that are produced domestically.

A notable exception is the work by Abreha (2019), who finds sizeable impacts of importing on productivity for Ethiopian manufacturing plants. Foster-McGregor et al. (2014) estimate labour productivity (sales per employee) premia between 79 and 113 per cent for two-way traders and between 36 and 64 per cent, respectively, for exporter-only and importer-only firms with the use of a cross-section of firm data for 19 sub-Saharan African countries. Unlike their study, we use a panel of firm data and measure productivity with the use of estimates of total factor productivity (TFP).

The transaction database includes firm-level information on the value, quantity, and destination/origin on trade flows at the 8-digit level of the Harmonized System (HS) over the period 2009–2014. To ensure consistency in product classification over time, the HS8-digit data were converted to the 6-digit level of the 2007 revision of the HS classification.

According to the World Bank Enterprise data for South Africa in 2007, indirect exporters and indirect importers make up 6.5 per cent and 16–18.5 per cent, respectively, of manufacturing firms. The World Bank Enterprise data shares of direct exporters and importers are broadly consistent with our shares that use the SARS data and range from 17 to 23% for exporters and 19–25 per cent for importers, depending on the sample weights that are used. The average share of direct exporters and importers over the 2009–2013 period based on the SARS data is calculated at 24 and 25 per cent, respectively (Edwards et al. 2018).

Participation in direct importing is unexpectedly low in the Motor vehicles industry. A possible explanation is that international trade in motor vehicles is conducted through subdivisions within the motor industry conglomerates as opposed to directly by the plant.

The correlation coefficient across industries of the fraction of exporters and importers is 0.9.

Bernard et al. (2018) find that the 3 percent of US manufacturing firm importers that sourced 11 or more products from 11 or more countries accounted for approximately 76 per cent of import value in the US for 2007. The top 5 percentiles of manufacturing firms by total trade (exports plus imports) in their data accounted for 94.9 per cent of the total value of imports. In contrast, the equivalent share for South African manufacturing firms that import is 60 per cent.

The estimates do not take into account firm exit as it is not possible to determine whether missing firm observations in the income tax database denote firm exit or failure to submit a tax return. See Kreuser and Newman (2018) for details on the estimates of the TFP.

We don’t have information on the educational qualifications of works. Consequently, we measure the skilled labour share as the share of workers within a firm who earn a salary of more than 20,000 Rands per month. Capital is measured as the sum of the value of fixed assets (property, plant, and equipment) that is reported by each firm.

Having an estimated parameter (TFP) as the dependent variable might in fact introduce heteroskedasticity (Saxonhouse 1976).

Background analysis of the data indicates that 43 per cent of the firms did not change importing status over the period.

If we assume that all intermediate goods are symmetrically produced, then this ratio is equal to the range of domestic inputs that are purchased relative to the total range available (Kasahara and Rodrigue 2008). The variable is calculated as the (cost of sales—direct imports)/cost of sales. This indicator will over-estimate the domestic share in costs for firms that use indirectly imported intermediate inputs in production.

High-income countries are defined according to the 2015 World Bank classification of countries by income. High-income economies are those with a gross national income per capita of US$12,736 or more. We also use OECD membership as our indicator of advanced economies. The results are very similar.

References

Abreha, K. G. (2019). Importing and firm productivity in ethiopian manufacturing. The World Bank Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhx009.

Ackerberg, D., Benkard, C. L., Berry, S., & Pakes, A. (2007). Econometric tools for analyzing market outcomes. In J. Heckman & E. Leamer (Eds.), Handbook of econometrics. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Amiti, M., & Konings, J. (2007). Trade liberalization, intermediate inputs, and productivity: Evidence from Indonesia. American Economic Review, 97(5), 1611–1638.

Bas, M. (2012). Input-trade liberalization and firm export decisions: Evidence from Argentina. Journal of Development Economics, 97(2), 481–493.

Bas, M., & Strauss-Kahn, V. (2014). Does importing more inputs raise exports? Firm-level evidence from France. Review of World Economics, 150(2), 241–275.

Bas, M., & Strauss-Kahn, V. (2015). Input-trade liberalization, export prices and quality upgrading. Journal of International Economics, 95, 250–262.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2007). Firms in international trade. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), 105–130.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2018). Global Firms. Journal of Economic Literature, 56(2), 565–619.

Broda, C., & Weinstein, D. E. (2006). Globalization and the gains from variety. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), 541–585.

Castellani, D., Serti, F., & Tomasi, C. (2010). Firms in international trade: Importers’ and exporters’ heterogeneity in Italian manufacturing industry. The World Economy, 33(3), 424–457.

Colantone, I., & Crinò, R. (2014). New imported inputs, new domestic products. Journal of International Economics, 92(1), 147–165.

Damijan, J. P., Konings, J., & Polanec, S. (2014). Import churning and export performance of multi-product firms. The World Economy, 37(11), 1483–1506.

de Loecker, J. (2007). Do exports generate higher productivity? Evidence from Slovenia. Journal of International Economics, 73(1), 69–98.

Eaton, J., & Kortum, S. (2001). Technology, trade, and growth: A unified framework. European Economic Review, 45, 742–755.

Edwards, L. (2001). Globalisation and the skill bias of occupational employment in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics, 69(1), 40–71.

Edwards, L. (2005). Has South Africa liberalised its trade? South African Journal of Economics, 73(4), 754–775.

Edwards, L., & Jenkins, R. (2015). The impact of Chinese import penetration on the south african manufacturing sector. Journal of Development Studies, 51(4), 447–463.

Edwards, L., Sanfilippo, M., & Sundaram, A. (2018). Importing and firm export performance: New evidence from South Africa. South African Journal of Economics, 86(S1), 79–95.

Erten, B., Leight, J., & Tregenna, F. (2019). Trade liberalization and local labor market adjustment in South Africa. Journal of International Economics, 118(May), 448–467.

Fan, H., Li, Y. A., & Yeaple, S. R. (2015). Trade liberalization, quality, and export prices. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97(5), 1033–1051.

Farole, T. (2016). Factory Southern Africa?: SACU in global value chains—Summary report. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

Feng, L., Li, Z., & Swenson, D. L. (2012). The Connection between Imported Intermediate Inputs and Exports: Evidence from Chinese Firms. NBER Working Paper 18260. Washington, D.C.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Foster-McGregor, N., Isaksson, A., & Kaulich, F. (2014). Importing, exporting and performance in sub-Saharan African manufacturing firms. Review of World Economics, 150(2), 309–336.

Goldberg, P. K., Khandelwal, A. K., Pavcnik, N., & Topalova, P. (2010). Imported intermediate inputs and domestic product growth: Evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(4), 1727–1767.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1991). Innovation and growth in the global economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Grossman, G. M., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2008). Trading tasks: A simple theory of offshoring. American Economic Review, 98(5), 1978–1997.

Halpern, L., Koren, M., & Szeidl, A. (2015). Imported inputs and productivity. American Economic Review, 105(12), 3660–3703.

Jenkins, R. (2008). Trade, technology and employment in South Africa. Journal of Development Studies, 44(1), 60–79.

Kasahara, H., & Lapham, B. (2013). Productivity and the decision to import and export: Theory and evidence. Journal of International Economics, 89(2), 297–316.

Kasahara, H., & Rodrigue, J. (2008). Does the use of imported intermediates increase productivity? Plant-level Evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 87(1), 106–118.

Khandelwal, A. (2010). The long and short (of) quality ladders. Review of Economic Studies, 77(4), 1450–1476.

Kreuser, F., & Newman, C. (2018). Total factor productivity in South African manufacturing. South African Journal of Economics, 86(S1), 40–78.

Kugler, M., & Verhoogen, E. (2009). Plants and Imported Inputs: New Facts and an Interpretation. American Economic Review, 99(2), 501–507.

Manova, K., & Zhang, Z. (2012). Export prices across firms and destinations. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127, 379–436.

Matthee, M., Rankin, N., Webb, T., & Bezuidenhout, C. (2018). Understanding manufactured exporters at the firm-level: New Insights from using SARS administrative data. South African Journal of Economics, 86(S1), 96–119.

Melitz, M. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

OECD. (2018). Trade in value added: South Africa. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Rodrik, D. (2008). Understanding South Africa’s economic puzzles. Economics of Transition, 16(4), 769–797.

Saxonhouse, G. R. (1976). Estimated parameters as dependent variables. The American Economic Review, 66(1), 178–183.

Schor, A. (2004). Heterogeneous productivity response to tariff reduction: Evidence from Brazilian manufacturing firms. Journal of Development Economics, 75(2), 373–396.

Topalova, P., & Khandelwal, A. (2011). Trade liberalization and firm productivity: The case of India. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(3), 995–1009.

Wagner, J. (2012). International trade and firm performance: A survey of empirical studies since 2006. Review of World Economics, 148(2), 235–267.

Wagner, J. (2016). A survey of empirical studies using transaction level data on exports and imports. Review of World Economics, 152(1), 215–225.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). On estimating firm-level production functions using proxy variables to control for unobservables. Economics Letters, 104(3), 112–114.

World Bank (2017). Measuring and analyzing the impact of GVCs on economic development. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

World Bank (2020). World Development Report 2020—Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor, Lawrence J. White, participants at the Economic Society of South Africa conference, 2015, and the South African National Treasury/UNU-WIDER/South African Revenue Services Policy seminar on ‘Firm-level analysis’, 2016 and to the Italian Trade Study Group Meeting at IMT, Lucca, Octover 2016, for their useful comments. Support from UNU-WIDER is gratefully acknowledged. The South African National Research Foundation (NRF) (Unique Grant No.: 93648/93660) provided additional support to cover subsistence and travel.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Edwards, L., Sanfilippo, M. & Sundaram, A. Importing and Productivity: An Analysis of South African Manufacturing Firms. Rev Ind Organ 57, 411–432 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-020-09765-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-020-09765-z