Abstract

Despite the long-identified relationship between poverty and risk for intimate partner violence (IPV) and non-intimate partner domestic violence (DV), there is limited work on the relationship between public anti-poverty programs and the incidence of such violence in the United States. In this study, we examine the effect of state Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC) on reports of lethal IPV and DV, a previously unstudied relationship. We offer a conceptual framework for understanding the potentially countervailing mechanisms by which state EITCs could affect lethal violence. We use a combination of empirical strategies, including new econometric estimators, to causally identify how changes in state EITCs affect the rate of reported IPV and DV, measured as homicide rates per 100,000 population. We find no significant causal effects of state EITC (presence or relative generosity) on lethal IPV or DV at a population level. Our work provides insight into the mechanisms at play, and suggests a role for more targeted policy interventions to mitigate individual effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This language is imperfect in cases such as incidents where the victim of IPV kills the perpetrator of IPV in self-defense, meaning that the IPV perpetrator is actually the homicide victim. Where necessary, we specify that the victim/perpetrator is with respect to IPV or the specific identified homicide.

However, it is also quite likely that short-run stability that keeps victims and abusers in a relationship may yield increased violence in the long run. As our study focuses on the short run, we leave this question to future researchers.

In many cases multiple agencies service the same county (e.g., a county sheriff’s department and a city police department). We choose to focus on the county-level analysis rather than agency-level analysis (clustering at the level of the county) because of data quality concerns in the agency-level data where some agencies do not consistently report. By aggregating to the county, we instead focus on a marginal analysis, assuming orthogonality of reporting bias to our variation of interest.

References

Abadie, A., Athey, S., Imbens, G., & Wooldridge, J. When Should You Adjust Standard Errors for Clustering? NBER Working Paper Series 24003 (2017). http://arxiv.org/abs/1710.02926. ArXiv: 1710.02926.

Abraham, S., & Sun, L. Estimating Dynamic Treatment Effects in Event Studies With Heterogeneous Treatment Effects. SSRN Electronic Journal (2019). ArXiv: 1804.05785.

Agan, A. Y., & Makowsky, M. M. The Minimum Wage, EITC, and Criminal Recidivism. Tech. Rep., National Bureau of Economic Research (2018). ArXiv: 1011.1669v3 Publication Title: NBER Working Paper Series ISBN: 9788578110796 ISSN: 1098-6596.

Aizer, A. (2010). The gender wage gap and domestic violence. American Economic Review, 100, 1847–1859.

Aizer, A., & Dal Bó, P. (2009). Love, hate and murder: Commitment devices in violent relationships. Journal of Public Economics, 93, 412–428. Publisher: Elsevier B.V.

Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). the impact of Covid-19 on gender equality. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 53, 1689–1699.

Anderberg, D., Rainer, H., Wadsworth, J., & Wilson, T. (2016). Unemployment and domestic violence: theory and evidence. Economic Journal, 126, 1947–1979.

Arenas-Arroyo, E., Fernandez-Kranz, D., & Nollenberger, N. (2021). Intimate partner violence under forced cohabitation and economic stress: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 194, 104350.

Averett, S., & Wang, Y. (2013). The effects of earned income tax credit payment expansion on maternal smoking. Health Economics, 22, 1344–1359.

Averett, S., & Wang, Y. (2018). Effects of higher EITC payments on children’s health, quality of home environment, and noncognitive skills. Public Finance Review, 46, 519–557.

Bassuk, E., Dawson, R., & Huntington, N. (2006). Intimate partner violence in extremely poor women: longitudinal patterns and risk markers. Journal of Family Violence, 21, 387–399.

Bastian, J., & Lochner, L. (2020). The earned income tax credit and maternal time use: more time working and less time with kids? NBER Working Paper Series, 27717, 1–70.

Bastian, J., & Michelmore, K. (2018). The long-term impact of the earned income tax credit on children’s education and employment outcomes. Journal of Labor Economics, 36, 1127–1163.

Bastian, J. E., & Jones, M. R. (2021). Do EITC expansions pay for themselves? Effects on tax revenue and government transfers. Journal of Public Economics, 196, 104355 Publisher: Elsevier B.V.

Baughman, R. A. (2005). Evaluating the impact of the earned income tax credit on health insurance coverage. National Tax Journal, 58, 665–684.

Baughman, R. A., & Duchovny, N. (2016). State earned income tax credits and the production of child health: insurance coverage, utilization, and health status. National Tax Journal, 69, 103–132.

Benson, M. L., & Fox, G. L. Economic distress, community context & intimate violence: An application & extension of social disorganization theory, final report. United States Department of Justice 1–166 (2002). http://ezproxy.neu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cja&AN=CJA0370040002612&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Benson, M. L., Fox, G. L., DeMaris, A., & Van Wyk, J. (2003). Neighborhood disadvantage, individual economic distress and violence against women in intimate relationships. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 19, 207–235.

Borusyak, K., & Jaravel, X. (2017) Revisiting Event Study Designs. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–25.

Borusyak, K., Jaravel, X., & Spiess, J. Revisiting event study designs: robust and efficient estimation. Tech. Rep. (2022). http://arxiv.org/abs/2108.12419. ArXiv: 2108.12419.

Boyd-Swan, C., Herbst, C. M., Ifcher, J., & Zarghamee, H. (2016). The earned income tax credit, mental health, and happiness. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 126, 18–38.

Browne, A., Miller, B., & Maguin, E. (1999). Prevalence and severity of lifetime physical and sexual victimization among incarcerated women. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 22, 301–322.

Callaway, B. (2021). Callaway and Sant’anna DD estimator. 1–14.

Callaway, B., & Sant’Anna, P. H. (2021). Difference-in-Differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics, 225, 200–230. ArXiv: 1803.09015.

Campbell, A. M. (2020). An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports, 2(2020), 100089.

Card, D., & Dahl, G. B. (2011). Family violence and football: The effect of unexpected emotional cues on violent behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126, 103–143.

Carr, J. B., & Packham, A. (2019). SNAP benefits and crime: Evidence from changing disbursement schedules. Review of Economics and Statistics, 101, 310–325.

Carr, J. B., & Packham, A. (2020). SNAP Schedules and Domestic Violence. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 40(2), 412–452.

Cesur, R., Rodriguez-Planas, N., Roff, J., & Simon, D. (2022). Domestic violence and income: Quasi-experimental evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit. NBER Working Paper Series, 29930, 1–47.

Chen, Z., & Woolley, F. (2001). A Cournot-Nash model of family decision making. Economic Journal, 111, 722–748.

Chetty, R., Friedman, John N., & Rockoff, J. (2011) New Evidence on the Long-term Impacts of Tax Credits. Washington, DC: US Internal Revenue Service.

Chin, Y. M., & Cunningham, S. (2019). Revisiting the effect of warrantless domestic violence arrest laws on intimate partner homicides. Journal of Public Economics, 179, 104072 Publisher: Elsevier B.V.

Chiou, L., & Tucker, C. E. (2020). Social Distancing, Internet Access and Inequality. NBER Working Paper Series, 26982, 1–27.

Cooper, A., & Smith, E. Homicide Trends in the United States, 1980-2008. Annual Rates for 2009 and 2010. Tech. Rep., U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics (2013). Issue: November ISSN: 00703370.

Corman, H., Dave, D. M., & Reichman, N. E. (2014). Effects of welfare reform on women’s crime. International Review of Law and Economics, 40, 1–14. Publisher: Elsevier Inc.

Crandall-Hollick, M. L. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): A Brief Legislative History. Tech. Rep., Congressional Research Service (2018). www.crs.gov.

Crowne, S. S., Juon, H.-S., Ensminger, M., Burrell, L., McFarlane, E., & Duggan, A. (2011). Concurrent and long-term impact of intimate partner violence on employment stability. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26, 1282–1304.

Dahl, G. B., & Lochner, L. (2017). The impact of family income on child achievement: Evidence from the earned income tax credit: Comment. American Economic Review, 107, 623–628.

Dahl, M., & Høyland, B. (2012). Peace on quicksand? Challenging the conventional wisdom about economic growth and post-conflict risks. Journal of Peace Research, 49, 423–429.

Daly, M., & Wilson, M. (1988). Evolutionary social psychology and family homicide. Science, 242, 519–524.

DeRiviere, L. (2008). Do economists need to rethink their approaches to modeling intimate partner violence? Journal of Economic Issues, 42, 583–606.

Drumble, M. L. A History of the EITC: How It Began and What It Has Become. In Tax Credits for the Working Poor, vol. 119, 5–24 (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Edmonds, A. T., Moe, C. A., Adhia, A., Mooney, S. J., Rivara, F. P., Hill, H. D., & Rowhani-Rahbar, A. (2021). The earned income tax credit and intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(13–14), NP12519–NP12541.

Eissa, N., & Hoynes, H. W. (2006). Behavioral responses to taxes: lessons from the EITC and labor supply. Tax Policy and the Economy, 20, 73–110.

Evans, M. L., Lindauer, M., & Farrell, M. E. (2020). A pandemic within a pandemic — intimate partner violence during Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 383, 2302–2304.

Evans, W. N., & Garthwaite, C. L. (2014). Giving mom a break: The impact of higher EITC payments on maternal health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6, 258–290.

Fagan, J. A., & Browne, A. (1994). Violence between spouses and intimates. Understanding and preventing violence, volume 3: Social influences, 1, 115–292.

Gardner, J., & Osei, B. (2022). Recreational marijuana legalization and admission to the foster-care system. Economic Inquiry, 60, 1311–1334.

Gibson, C. L., Swatt, M. L., & Jolicoeur, J. R. (2001). Assessing the generality of general strain theory: The relationship among occupational stress experienced by male police officers and domestic forms of violence. Journal of Crime and Justice, 24, 29–57.

Goodman-Bacon, A. (2020). Difference-in-Differences with Variation in Treatment Timing. Working paper, 1–49.

Harpur, P., & Douglas, H. (2014). Disability and domestic violence: protecting survivors’ human rights. Griffith Law Review, 23, 405–433.

Hoynes, H., Miller, D., & Simon, D. (2015). Income, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Infant Health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7, 172–211.

Hoynes, H. W. The Earned Income Tax Credit, Welfare Reform, and the Employment of Low-Skilled Single Mothers. In Toussaint-Comeau, M., & Meyer, B. D. (eds.) Strategies for Improving Economic Mobility of Workers: Bridging Research and Practice (Upjohn Press, 2009).

Hsu, L.-C. (2017). The timing of welfare payments and intimate partner violence. Economic Inquiry, 55, 1017–1031.

Internal Revenue Service. Statistics for Tax Returns with EITC (2020). https://www.eitc.irs.gov/eitc-central/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-eitc/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-eitc.

Isaac, E. (2020). Marriage, divorce, and social safety net policy. Southern Economic Journal, 86, 1576–1612.

Kim, J., & Gray, K. A. (2008). Leave or stay?: Battered women’s decision after intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23, 1465–1482.

Kimerling, R., Alvarez, J., Pavao, J., Mack, K. P., Smith, M. W., & Baumrind, N. (2009). Unemployment among women: examining the relationship of physical and psychological intimate partner violence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 450–463.

Lanier, C., & Maume, M. O. (2009). Intimate partner violence and social isolation across the rural/urban divide. Violence Against Women, 15, 1311–1330.

Lenhart, O. (2019). The effects of state-level earned income tax credits on suicides. Health Economics (United Kingdom), 28, 1476–1482.

Lenhart, O. Earned Income Tax Credit and crime. Contemporary Economic Policy 1–19 (2020).

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. Bargaining and distribution in families. In The well-being of children and families: Research and data needs, pp. 314–338 (University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI, 2001).

Manoli, D., & Turner, N. (2018). Cash-on-hand and college enrollment: evidence from population tax data and the earned income tax credit. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 10, 242–271.

Markowitz, S., Komro, K. A., Livingston, M. D., Lenhart, O., & Wagenaar, A. C. (2017). Effects of state-level earned income tax credit laws in the U.S. on maternal health behaviors and infant health outcomes Sara. Social Science and Medicine, 194, 67–75.

Max, W., Rice, D. P., Finkelstein, E., Bardwell, R. A., & Leadbetter, S. (2004). The economic toll of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Violence and Victims, 19, 259–272.

Meyer, B. D. (2010). The effects of the earned income tax credit and recent reforms. Tax Policy and the Economy, 24, 153–180.

Michelmore, K. (2018). The earned income tax credit and union formation: The impact of expected spouse earnings. Review of Economics of the Household, 16, 377–406.

Miller, A. R., & Segal, C. (2019). Do female officers improve law enforcement quality? Effects on crime reporting and domestic violence. The Review of Economic Studies, 86, 2220–2247.

Moe, C. A., Adhia, A., Mooney, S. J., Hill, H. D., Rivara, F. P., & Rowhani-Rahbar, A. (2020). State Earned Income Tax Credit policies and intimate partner homicide in the USA, 1990-2016. Injury prevention : journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention, 26, 562–565.

National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Statistics (2020). https://ncadv.org/STATISTICS.

Neumark, D., & Wascher, W. (2002). State-level estimates of minimum wage effects: New evidence and interpretations from disequilibrium methods. Journal of Human Resources, 37, 35–62.

Petrosky, E., Blair, J. M., Carter, J., Betz, J., Fowler, K. A., Jack, S. P. D., and Lyons, B. H. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Homicides of Adult Women and the Role of Intimate Partner Violence — United States, 2003–2014. Tech. Rep., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/cme/conted_info.html#weekly. Volume: 66 Issue: 28.

Puzone, C. A., Saltzman, L. E., Kresnow, M.-j, Thompson, M. P., & Mercy, J. A. (2000). National trends in intimate partner homicide: United States, 1976-1995. Violence Against Women, 6, 420–426.

Quinn, B. The Nation’s Two Measures of Homicide. Tech. Rep., U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs (2014). https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ntmh.pdf.

Sant’Anna, P. H., & Zhao, J. (2020). Doubly robust difference-in-differences estimators. Journal of Econometrics, 219, 101–122.

Scholz, J. K. (1994). The earned income tax credit: participation, compliance, and antipoverty effectiveness S. National Tax Journal, 47, 63–87.

Schwab-Reese, L. M., Peek-Asa, C., & Parker, E. (2016). Associations of financial stressors and physical intimate partner violence perpetration. Injury Epidemiology, 3, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-016-0069-4. Publisher: Injury Epidemiology.

Internal Revenue Service. (2022) Earned Income and Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) Tables. https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/earned-income-tax-credit/earned-income-and-earned-income-tax-credit-eitc-tables.

Showalter, K., Yoon, S., & Logan, T. The Employment Trajectories of Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. Work, Employment and Society 095001702110352 (2021). http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/09500170211035289.

Sims, K. M. (2023) Seeking safe harbors: Emergency domestic violence shelters and family violence. Working Paper, 1–61.

Strube, M. J., & Barbour, L. S. (1983). The decision to leave an abusive relationship: economic dependence and psychological commitment. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 785.

Strully, K. W., Rehkopf, D. H., & Xuan, Z. (2010). Effects of prenatal poverty on infant health: state earned income tax credits and birth weight. American Sociological Review, 75, 534–562. ArXiv: NIHMS150003 ISBN: 6176321972.

Sullivan, C. M., Goodman, L. A., Virden, T., Strom, J., & Ramirez, R. (2018). Evaluation of the effects of receiving trauma-informed practices on domestic violence shelter residents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88, 563–570.

Sun, L., & Abraham, S. (2021). Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. Journal of Econometrics, 225, 175–199.

Swanberg, J. E., Ojha, M. U., & Macke, C. (2012). State employment protection statutes for victims of domestic violence: public policy’s response to domestic violence as an employment matter. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 587–619.

Tauchen, H. V., Dryden Witte, A., & Long, S. K. (1991). Domestic violence: a nonrandom affair. International Economic Review, 32, 491–511.

The Urban Institute. State Earned Income Tax Credits (2020). https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/state-and-local-finance-initiative/state-and-local-backgrounders/state-earned-income-tax-credits.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Fall competition at UW-Madison and the Kohl Competition at La Follette School of Public Affairs, UW-Madison. Thanks are due to attendees of the 2022 Virtual Crime Economics Workshop for their helpful comments and feedback. The authors thank Licheng Xu for research assistance and the editor and anonymous referees for their constructive and supportive feedback.

Author contributions

All authors conceptualized the project. YW and BW secured internal funding for the project. K.M.S. provided the outcome data, designed the empirical strategy, cleaned the data, and carried out the formal analysis. YW and BW provided data on the treatment variable of interest. K.S. wrote the initial draft. All three authors collaborated on reviewing, editing, and revising the draft.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Intrest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Appendices

Appendix A: Data appendix

Data on state EITC levels (as a percentage of the federal EITC), changes to state EITC policies, and refundability were collected from the National Bureau of Economic Research. Table 8 categorizes states by whether or not the state EITC is tax-refundable. In Table 7, we describe state EITC policies including years of implementation and generosity.

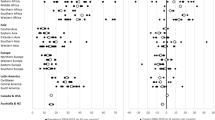

Appendix B: Event study graphs

Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021) event study graphs of treatment effect of binary EITC presence on IPV/DV homicide, controlling for non-IPV/DV homicide, and county unemployment

Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021) event study graphs of treatment effect of refundable EITC presence on IPV/DV homicide

Sun and Abraham (2021) event study graphs of treatment effect of binary EITC presence on IPV/DV homicide, controlling for non-IPV/DV homicide, and county unemployment

Sun and Abraham (2021) event study graphs of treatment effect of refundable EITC presence on IPV/DV homicide, controlling for non-IPV/DV homicide, and county unemployment

Appendix C: Additional results

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sims, K.M., Wang, Y. & Wolfe, B. Estimating impacts of the US EITC program on domestic violence. Rev Econ Household (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-024-09702-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-024-09702-z