Abstracts

The healthcare that a woman receives during pregnancy, at the time of delivery, and soon after delivery is imperative for the well-being and survival of both the mother and her child. Hence, understanding the factors that influence the utilization of healthcare around the period of birth is important for improving the health of the mother and her child as well as reducing maternal mortality. Although numerous studies have examined the factors that influence the utilization of healthcare around the period of birth, no study has considered the role of ethnic heterogeneity. This paper bridges a significant gap in the literature by reporting findings from the first study that examines the effect of ethnic heterogeneity on healthcare utilization in Ghana. The study utilized data from both the Demographic Health Survey and Ghana Population and Housing Census. Our estimates show that a unit increase in a heterogenous ethnic group lowers the likelihood of utilizing healthcare at the time of birth and after delivery via increasing household poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Healthcare utilization defined as how much and the type of healthcare people use as well as the timing of that care is an important policy focus in both emerging and developed economies. In emerging economies, the policy focus has mainly been increasing healthcare utilization among women at the time of birth. The importance of increasing healthcare utilization among women at the time of birth is reflected in the Sustainable Development Global Goals (SDGs). Thus, one of the objectives of the SDGs is to decrease maternal mortality to 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030. The first step involved in decreasing maternal mortality is to increase healthcare utilization at the time of birth. Improving healthcare utilization at the time of birth requires a better understanding of its root causes. As a result, many studies have examined what, why, and how, economic factors affect healthcare utilization (Grand-Guillaume-Perrenoud et al., 2022, Haruna et al., 2019). For example, Agyemang-Duah et al. (2019) find that one of the economic factors that decreases the utilization of health in Ghana is the cost associated with using healthcare. A subset of these studies has also focused on understanding how socioeconomic factors including culture, racism, effective communication, religion, and others influence the utilization of healthcare among women at the time of birth (Paine et al., 2018, Agyemang-Duah et al., 2021, Ravensbergen et al., 2019). For instance, Agyemang-Duah et al. (2021) find that communication is a major barrier to healthcare utilization in Ghana. Yet, despite the growing interest in understanding the link between healthcare utilization at the time of birth and economic and socioeconomic factors, no study has attempted to examine the link between ethnic heterogeneity, and healthcare utilization.

This study bridges an important literature gap by asking the following questions: Does ethnic heterogeneity increase or decrease healthcare utilization? Can poverty mediate the relationship between ethnic heterogeneity and healthcare utilization? To answer these questions, necessitate data with information on poverty, healthcare utilization, and ethnic heterogeneity. Data on healthcare utilization and poverty are drawn from 2019 and 2014 Demographic Health Survey (DHS) data whereas data on ethnic heterogeneity is obtained from the 2010 Ghana Population and Housing Census (GPHC). To measure linguistic and ethnic heterogeneity, we followed Alesina & Zhuravskaya (2011) who provide indexes of linguistic and ethnic fractionalization at national and regional or sub-national levels. The indexes of linguistic and ethnic fractionalization reflect two randomly selected individuals in a region or country who belong to different linguistic or ethnic groups living in an area or society. Thus, ethnic diversity shows heterogeneity between people of different ethnic groups that exist in a society. Simply put, ethnic diversity shows the level of division or concentration of ethnic groups in a geographical area. Also, our preferred measure of poverty is drawn from Alkire & Santos (2010) who provide a multidimensional poverty index (MPI) at the household level. The multidimensional poverty index captures three main household characteristics, namely health, education, and household living standards. The index is constructed using the household’s deprivation of necessities of life. The use of this measure of poverty is important given the lack of information on the expenses of a household relating to poverty in most survey data. Lastly, we adopt two broad measures of healthcare utilization, following standards set by the World Health Organization and existing studies (Kim & Lee, 2016, Organization, 2002). Specifically, we utilize delivery, and antenatal care at the health facility, seeking for WHO-recommended set of vaccinations for children after delivery and after-delivery checkups from health professionals as the measures of healthcare utilization at the time of birth. Using these four different broad measures of healthcare utilization is very important because aside from serving as a robustness check, they extend the healthcare utilization literature. The main finding that emerges from this study is that a unit increase in heterogeneous ethnic groups lowers healthcare utilization at the time of birth. Our explicit explanation for this finding is that poverty prevalence in heterogenous ethnic societies mitigates the utilization of healthcare.

Ghana is an ideal country to study the impact of ethnic heterogeneity on healthcare utilization due to the following reasons. First, government and international organizations such as the World Health Organization have developed numerous strategies and policies to increase healthcare coverage in Ghana, but utilization remains relatively low. Prominent among these strategies include the call for universal health coverage (UHC) which is defined by WHO as a state where communities and individuals receive the healthcare services they need without cost. One unique strategy that looks promising is free maternal healthcare which allows pregnant women to get access to free healthcare services. Despite these recent efforts to improve healthcare coverage, utilization of antenatal and postnatal healthcare remains relatively low across some specific genders and demographics. Rural areas often have no modern healthcare services. Patients in these areas either rely on traditional African medicine or travel great distances for healthcare at the time of birth (Novignon et al., 2019, Alhassan et al., 2019). Women also underutilize antenatal and postnatal healthcare in Ghana. For example, Nuamah et al. (2019) reported that nearly 68.5% of women in the Ashanti Region of Ghana had less than 3 antenatal care visits. Poor, vulnerable, and diverse communities also underutilized healthcare in Ghana due to a lack of healthcare facilities (Novignon et al., 2019, Alhassan et al., 2019, Nuamah et al., 2019). Second, Ghana is one of the African countries with the most ethnically heterogeneous societies. Estimates from our data and Fearon (2003) show that the ethnic fractionalization scores for Ghana are 0.791 and 0.846, respectively. This makes Ghana a top country in Africa with ethnically diverse communities and ahead of countries in Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and Latin America. The score also indicates Ghana is ranked 12th among countries with heterogenous ethnic societies. Ghana is even recognized as a more ethnically diverse country compared to Nigeria which is globally known to have many more heterogeneous societies.

This study makes a unique contribution to the literature by examining the direct effect of ethnic heterogeneity on the utilization of healthcare at the time of birth. Most importantly, it also examines if poverty mediates the relationship between ethnic heterogeneity and healthcare utilization in Ghana. Understanding these relationships is very important because it does not only contribute to the literature that seeks to understand the root causes of healthcare utilization but also provides new insight for policymakers. Thus, the findings from this study are very important to policymakers, governments, and international bodies that seek to improve the utilization of healthcare in developing countries. Specifically, the findings from this study are important to the United Nations member states that seek to reduce maternal mortality to 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030. One of the potential means to achieve this is to increase healthcare utilization during pregnancy, at the time of delivery, and soon after delivery. However, increasing utilization of healthcare requires a better understanding of the factors that influence it. This study has identified that ethnic heterogeneity influences healthcare utilization through poverty. Hence, aside from economic factors such as the cost of healthcare, health insurance, and others, socio-cultural factors such as ethnic heterogeneity play a crucial role in healthcare utilization. As such policymakers should give ample attention to alleviating poverty in heterogeneous ethnic societies when devising policies aimed at increasing healthcare utilization. The bottom line is that good economic policy alone may not be sufficient to increase healthcare utilization. Hence, aside from the usual prescription of good economic policies, “nation-building” policies that foster the development of a common national identity might be needed to improve healthcare utilization.

2 Brief overview of ethnic heterogeneity in Ghana

Ghana is one of the African countries with a high degree of linguistic heterogeneity. The basis of Ghana’s heterogeneity is seen in different languages spoken and other cultural traits (Bodomo, 1996). The indigenous languages spoken in Ghana can be categorized into ten major groups with over sixty-seven sub-groups as shown in Fig. 1. Specifically, Fig. 1 demonstrates how sixty-seven ethnic groups are distributed across the ten regions in Ghana. It is observed that none of the ten regions in Ghana is ethnically homogenous, an overriding feature of the country’s ethnic polarization is a north–south divide. The ethnic group that dominates the southern half is the Akan. The urban centers, particularly in the south, are the most ethnically diverse because of migration.

Distribution of sub-ethnic groups in Ghana. Source: Ansah (2014).

The five main dominant ethnic groups in Ghana are the Akans, Ewe, Mole Dagbane, Ga-Adangbe, and Guan. Out of these five dominant ethnic groups, the Akan group is the largest followed by Mole Dagbane and the smallest is the Guan as shown in Fig. 2. In Ghana, ethnicity is an important determinant of identity. People are socialised to believe that each person belongs to a community with shared origins, history, and identity that speaks one common language (Anyidoho & Dakubu, 2008). The language spoken is directly linked to people’s identity, politics, and the ethnic groups they belong. Ethnic identity and languages spoken are the symbols and values that form a focal point for ethnic group cohesiveness in Ghana, and this may vary through time and its intensity diffuses with time as well.

Distribution of the five main ethnic groups in Ghana. Source: Ansah (2014)

The spirit of affection among ethnic groupings extend to forming political associations. In Ghana, political parties are formed based on ethnicity which has led to some top political positions, and state institutions being occupied by some specific ethnic groups (Chazan, 1982). Individuals who do not belong to such an ethnic group find it difficult to compete or take up such positions. Also, the state institutions employ people in line with the ethnicity of the party in power making it difficult for people from diverse backgrounds to find jobs in state institutions. This creates social exclusion and high inequality gap between different ethnic groups (Addai & Pokimica, 2010). For example, the Asantes, and Ewes have consistently taken entrenched political positions since 1992. As a result, most state institution employees are either Akans or Ewes leaving out other minor ethnic groups. This has created a huge inequality gap between Akans/Ewes and other ethnic groups in Ghana(Addai & Pokimica, 2010). Since the minor ethnic groups are not able to take up political positions, the regions in which they are located remain underdeveloped because of a lack of infrastructural development. For instance, since colonial times, the northern parts occupied by the Mole Dagbane remain relatively underdeveloped because infrastructural development in health, education, and productive projects has been concentrated in the south occupied by the Akans.

3 Overview of antenatal and postnatal healthcare provision in Ghana

The main goal of antenatal and postnatal healthcare is to promote the wellbeing, and health of the pregnant woman and her child (Arthur, 2012). It aims to detect and manage risk factors in pregnancy. Using antenatal and postnatal healthcare services appropriately is important as it helps caregivers identify the risk factors associated with pregnancy and after delivery early. Failure to use antenatal and postnatal healthcare during pregnancy periods can result in undesirable pregnancy outcomes including low birth weight, neonatal mortality, maternal mortality, and stillbirth (Magadi et al., 2000, Bulatao & Ross, 2003).

In Ghana, antenatal and postnatal care are provided free of charge in all government hospitals but some religious and private hospitals provide them at a fee (Arthur, 2012). Although it is estimated that antenatal and postnatal care coverage in Ghana is 87%, adequate utilization (expectant mothers who attend a minimum of four visits) remains stagnant standing at 60% (Owen et al., 2020, Arthur, 2012). Low utilization of antenatal healthcare led to the introduction of the “cash and carry system” policy in 1985. This policy reduced the cost of utilizing antenatal healthcare services, especially among the poor. In September 2003, the policy was upgraded to exempt users from paying delivery fees in the four most deprived regions of the country; Central, Upper East, Upper West, and the Northern regions. The policy was extended to the remaining six regions of the country in April 2005. The main goal of the policy was to increase utilization of antenatal healthcare by reducing the cost associated with them. The reason why this policy was introduced is that cost of maternal healthcare services served as a hindrance to using these health services.

In 2008, the free maternal healthcare policy (FMHCP) was integrated into the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) which began in 2005. Under the NHIS, the FMHCP provided full cover for all costs associated with both antenatal and maternal healthcare services. Specifically, the policy provided a full maternal benefit package covering free antenatal visits; emergency outpatient visits; free facility delivery including all complicated deliveries and two postnatal visits within six weeks; waives the premium on the NHIS as well as the registration fees, and covers the pregnant woman for a year, as well as the newborn baby for the first three months of life (Owen et al., 2020, Anafi et al., 2018). The only eligibility criterion for the FMHCP is for the pregnant woman to provide evidence of the pregnancy from a valid health facility. Pregnant women who have never been on the scheme or do not have valid NHID cards can also get access by providing evidence of being pregnant. Women who provide evidence of their pregnancy get exempted from the NHIS registration/premium fees and have access to the ‘free’ antenatal and maternal health services.

4 Why should ethnic heterogeneity influence healthcare utilization?

Conceptually, several arguments can be advanced for why ethnic heterogeneity might affect healthcare utilization. A priori, the effect of ethnic heterogeneity on healthcare utilization is expected to be negative. Theoretical and empirical literature demonstrate that ethnic diversity is associated with a higher level of poverty (Becker, 2010, Gradín et al., 2010, Churchill & Smyth, 2017, Gereke et al., 2018, Miguel, 2006). From a theoretical perspective, the underlying logic is that ethnic, and linguistic fragmentation may result in labour market discrimination and occupational segregation, which contributes directly to loss of income and, hence, higher levels of poverty (Gradín et al., 2010). From an empirical perspective, the underlying reason is that that various ethnic groups dislike mixing across ethnic lines, and this results in weaker collective action to reduce poverty (Miguel, 2006, Gereke et al., 2018, Churchill & Smyth, 2017). Also, ethnic diversity generates poverty because communities with heterogeneous ethnic groups cannot agree on a suitable type of public good provision, leading to less funding for the public goods in such a community (Churchill & Smyth, 2017, Miguel, 2006). Less funding for publics goods tends to reduce the availability of public healthcare facilities which has been shown to correlate with low utilisation of healthcare services (Baker Jr et al., 2005, Tian et al., 2019). Furthermore, poor people may not be able to pay for healthcare cost associated with healthcare utilization which discourage the use of healthcare services. For example, McNamee et al. (2009) find that women in poorer groups of the population underutilize maternal healthcare services around the time of birth in low and middle-income countries.

The lower level of trust associated with ethnic diversity can also reduce healthcare utilization (Sturgis et al., 2011, Dincer, 2011, Robinson, 2020). The lower level of trust in ethnically diverse communities increases dissent, creates hatred, and weakens social networks all of which reduces participation in social groups (Barnes–Mauthe et al., 2013, Dionne, 2015). This engenders social exclusion which reduces utilization of healthcare in ethnically diverse communities (Hossen and Westhues, 2010, Parmar et al., 2014). Trust-effect of ethnic diversity can also lower healthcare utilization through communication gaps. Lower levels of trust among people living in ethnically diverse societies can widen communication gaps that mitigate the flow of information regarding optimal healthcare opportunities and could influence the use of healthcare services.

Different ethnic groups lack consensus on relevant public goods which slows down investment in physical infrastructure and the provision of public goods (Miguel & Gugerty, 2005, Alesina et al., 1999). Specifically, different ethnic groups are unable to agree on an important public good which can lower the optimal provision of healthcare facilities in ethnically diverse communities. Lack of healthcare facilities can lower the utilization of healthcare.

Social disorganization and lower level of trust associated with ethnic diversity promotes conflict and hatred which is likely to reduce healthcare utilization. Disagreement between ethnic groups tends to breed conflicts and crime (Kanbur et al., 2011, Bleaney & Dimico, 2017). Furthermore, inequality among ethnic groups breeds anger, frustration, and antisocial behaviour which create unfavourable business environment and thus discourage physical investment (Harris, 1996). Lower physical investment is associated with poor healthcare facilities which correlates with low healthcare utilization (Tian et al., 2019).

Finally, different ethnic groups in ethnically diverse communities consider various means to sustain their unique identities and interest. This is likely to make one ethnic group superior to other ethnic groups because it reinforces a hierarchical society along ethnic lines which promotes prejudice and discrimination (Churchill & Smyth, 2017). Such discrimination and prejudice tend to lower utilization of healthcare (Frank et al., 2014, Alcalá & Cook, 2018). Furthermore, discrimination is associated with occupational segregation which contributes to low healthcare utilization through loss of income.

5 Methodology

This section presents data, variables, and estimation strategies employed in the study.

5.1 Data

The study utilizes data from Demographic health survey data which is a nationally representative survey data that is conducted across many developing countries. DHS survey has conducted a series of surveys, but the present study uses the DHS rounds of 2014 and 2019 for Ghana which covers an average of approximately 9394 women in each survey rounds. Each survey round contains a separate data set for children, household members, couples, men, women, birth, and others. For this study, we utilize the women’s data set that contains information on women and their children. The data set contains rich information on healthcare utilization making it appropriate for this study. It also contains relevant information on demographic characteristics, socioeconomic characteristics, and health. The women sampled in each household are aged from fifteen (15) to forty-nine (49). Since the study focuses on the healthcare utilization of women around the period of birth, we restrict the sample to women aged 15–40 years of age. This is because women within this age category are more fertile, and thus are more likely to give birth compared to women outside this age range. This increases the likelihood that these women will utilize healthcare facilities that provide maternal and antenatal healthcare services during pregnancy periods and after birth.

To compute indices of ethnic heterogeneity, the study utilized information from the 2010 Population and Housing Census(GPHC) (Service, 2013). The data was conducted by Ghana Statistical Services which covered 24,658,823 individuals in 10 different administrative regions in Ghana. The main goal behind utilizing this data set includes but is not limited to: (1) It is the closest to the date on which the two waves of DHS data sets were conducted, (2) The 2010 GPHC contains extensive information on ethnicity and language at both national, regional, and district levels and, (3) Several studies have utilized this data set to compute ethnic diversity in Ghana (Koomson and Churchill, 2021, Awaworyi Churchill & Danquah, 2022, Sefa-Nyarko, 2021).

5.2 Ethnic heterogeneity

The study followed the approach of the Herfindahl fractionalization index (Greenberg, 1956) and existing studies in the literature (Churchill & Smyth, 2017, Awaworyi Churchill & Danquah, 2022) to measure ethnic heterogeneity. Mathematically, the index of diversity is computed as:

Where \({n}_{{ij}}\) is the share of ethnic group \(i\) in district \(j\). The ethnic fractionalization or ethnic heterogeneity index (\({{Ethnic\; diversity}}_{i}\)) captures the likelihood two individuals randomly selected in each district belong to different ethnic groups. The index ranges from 0 to 1 with a value of 0 indicating homogenous ethnic society, and 1 suggesting that every individual in a neighbourhood belongs to a different ethnic group. Thus, increasing the index of fractionalization suggests an increase in diversity (Alesina et al., 2003). The ethnicity index was computed using 216 districts based on the 2010 GPHC. The GPHC data has detailed information on the ethnic groups of the respondents across different districts. Specifically, the GPHC data reported information on 67 ethnic groups of respondents across 216 districts in their respective respondent locations. Providing information on where the respondents live give an accurate geographical identifier that allows us to compute district-level ethnic heterogeneity. This index is then merged with the DHS data set.

To provide a robustness check to our main estimation, we utilized an alternative ethnic heterogeneity measure by Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (2005) who measured ethnic diversity using ethnic polarization. This alternative approach is mathematically expressed as:

Where \({n}_{{ij}}\) is the same as Eq. (1). Here, ethnic polarization depicts the conflict dimension of heterogeneous ethnic groups. This measure captures the distance between the distribution of ethnic groups that leads to optimal conflict. The size of the ethnic group determines the extent of polarization given that distance among the groups is assumed to be equal. Thus, in this context, high ethnic polarization shows the closer the distribution of ethnic groups in each district.

5.3 Healthcare utilization

The focus of this study is to examine if ethnic diversity influences healthcare utilization among women. As a result, the study followed World Health Organization standards and previous studies and carefully selected four different proxies under two broad healthcare utilization indicators that capture healthcare use among women around the period of pregnancy and after delivery (Organization, 2002, Kim & Lee, 2016). These healthcare utilization indicators are described below:

-

(1)

Antenatal care: These include (a) A binary variable set equal to 1 if a woman gave birth at a healthcare facility (HF) and zero otherwise, and (b) A binary variable that takes one binary variable set equal one when the woman sought antenatal care at a healthcare facility provided by professional healthcare attendant (ATF) and zero otherwise.

-

(2)

Checkups after delivery: These include (a) A binary variable that takes the value of 1 if a woman completed the full WHO-recommended set of vaccinations (VCC), (b) A binary indicator set equal to one if respondents sought health care after delivery from either doctor or nurse, midwife, or community health officer/nurse (PHCAD) and zero otherwise. All these healthcare utilization indicators were captured based on the women’s current birth.

5.4 Measuring poverty

We adopt the multidimensional poverty index (MPI) developed by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (Alkire & Santos, 2010) to measure poverty in this study. This measure of poverty captures three main household indicators, namely household living standards, education, and health. However, under these three main indicators, sub-indicators are also considered. Specifically, following the MPI index, we use two sub-indicators under health and education and six indicators of living standards. For three main indicators, we applied a weight of 1/3 is applied to each indicator. For the sub-indicators, a weight of 1/6 is assigned to the sub-indicators under health and education whereas a weight of 1/18 is assigned to the sub-indicators under the living standard. See Table 7 in the appendix for the indicators in the DHS dataset used under each dimension. The MPI index is based on the deprivation score that is assigned to each household.

To compute the deprivation score per household, the weighted sum of the number of deprivation scores is taken. The score for each household ranges between 0 and 1. The score increases as the number of deprivations increases until it attains a maximum of 1 when a household is deprived in all indicators. Put differently, the poverty score is a weighted sum of the number of deprivation and ranges between 0 and 1.

The multidimensional poverty deprivation index is given as:

Where \({d}_{i}\) is household deprivation score, \({I}_{i}\) = 1 if the household is deprived of indicator i and \({I}_{i}\) = 0 if otherwise. \({w}_{i}\) is the weight attached to indicator i with \(\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{d}{w}_{i}=1\).

We use the MPI score of the household as a measure of poverty. The score ranges between 0–1 where a higher MPI score indicates a poorer household.

5.5 Covariates

To isolate the impact of ethnic heterogeneity on healthcare utilization, we include a standard set of covariates following previous studies (Apt, 2013, Gyasi et al., 2019). Thus, we include both household and individual-level control variables in our regression model. The household level covariates include household wealth index, household head age, residence (rural), and household size whereas the individual level covariates include the type of insurance coverage (public insurance), employment status, gender, marital status, age, and educational attainment. Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for all the variables used in the study. We observe that the average ethnic fractionalization is 0.791, suggesting that most individuals (i.e., 7 out of 10 people) in a particular district belong to a different ethnic group. The average MPI index is 0.689 for both data sets on a scale of 0 to 1 where 1 represents the least poor and 1 signifies the poorest. This average value of 0.689 indicates that the typical Ghanaian household is likely to be poorer. For both data sets, we observe that the average age of household heads for a typical Ghanaian household is 46.374 years with an average of 7.011 household members. Also, the average age of women in our sample for both data sets is 30.131 which is within the fertility age. This suggests that women in our sample are more likely to give birth, increasing the likelihood that they will utilize maternal and antenatal healthcare services.

5.6 Estimation strategy

Given the binary nature of all the dependent variables, the study adopts a probit model where all the binary outcomes are regressed on ethnic diversity and control variables. Mathematically, the reduced empirical model is expressed as:

Where \({HU}\) is the various measure of utilization of healthcare for a woman \(i\) in district \(j\) at time \(t\).\({ED}\) measures ethnic heterogeneity for district \(j\), whereas \(J\) is a set of household and individual level characteristics that correlate with healthcare utilization for women at the time of birth and after delivery. \({\alpha }_{r}\) and \({z}_{t}\) capture regional and time-fixed effects, whereas \(\varepsilon\) represents error terms respectively. Healthcare utilization around the period of birth and after delivery is persistent among women, especially for a short period, hence, we are unable to estimate fixed-effect models. Thus, estimating Eq. (4) with the panel probit fixed effect model is implausible. Therefore, we use the standard ordinary least square approach (OLS) to estimate Eq. (1) to produce our baseline results. As a more robustness check and to eliminate fixed effect issues, we also conducted a separate analysis for the two different rounds of the survey (DHS 2014 and 2019 specifically).

One issue that is common in empirical analysis is measurement errors. This issue occurs when there is a significant deviation of the measured value of a variable from its true value. This often occurs when respondents in a survey provide bias responses. In our case, the survey may not report several sub-ethnic groups in Ghana. For instance, there are numerous sub-groups of the Akan ethnic groups like Akyem, Nzima, Ahanta, and others that are not reported, leading to biases in the measure of ethnic diversity. Another issue that cannot be overlooked is the omitted variable problem. This is a problem because we cannot control all the relevant covariates that correlate with healthcare utilization and ethnic diversity. For instance, the regression model estimates the effect of ethnic diversity on healthcare utilization, but we are unable to control for the cost of using health at the time of birth and after delivery. Another source of endogeneity is unobserved characteristics of each ethnic group such as cultural traits (i.e., language, clothing, food), sense of community and others which can impact utilization of healthcare. Another unobserved characteristic is family circumstances such as income loss through unplanned natural shock which can influence healthcare utilization.

To minimize potential endogeneity issue, we control for rich set of covariates such as household wealth, health insurance coverage, and others (See Table 1 for full set of covariates) that are likely to influence healthcare utilization. These covariates can help reduce endogeneity emanating from omitted variables bias. To account for unobserved characteristics, we control for regional fixed effects that account for permanent differences across regions, that may simultaneously influence healthcare utilization. For instance, the regional fixed effect may account for regional differences in availability and cost of healthcare utilization. Intuitively, regional fixed effects are likely to minimize endogeneity resulting from unobserved characteristics.

To ensure that our results are robust, we utilize two alternative strategies to conduct robustness checks. First, we utilize the traditional two stage least square that utilizes an external instrument. Here our external instrument regional-level measure of diverse ethnic groups computed from the older population census evident in previous studies (Akay et al., 2017, Awaworyi Churchill & Farrell, 2020, Awaworyi Churchill et al., 2019). Regional level of ethnic diversity is expected to correlate with district level of ethnic diversity because the geographical pattern in a region reflects the pattern of the district or other small geographical areas in the region. However, we expect no direct correlation between regional-level and healthcare utilization. In our second robustness check, we employ the Lewbel (2012) 2SLS approach that generates an internal instrument to increase the predictive power of the external instrument. This approach builds an internal instrument by utilizing heteroskedasticity in the data. The approach has been employed by numerous studies in a situation where the external instrument is weak or unavailable (Patra et al., 2016, Appau et al., 2020, Awaworyi Churchill and Mishra, 2017).

6 Results

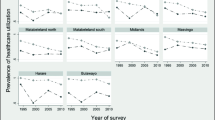

Tables 2, 3 report the baseline estimates of the effect of ethnic diversity on healthcare utilization. However, the results in Table 2 are from regressions without relevant covariates whereas the results in Table 3 are drawn from a regression that included a standard set of control variables. In both Tables, Panel A presents the results of using the 2019 DHS survey whereas Panel B reports the results of using the 2014 DHS survey. Panel C presents the estimates for combining the 2019 DHS and 2014 DHS data sets. Estimates across all the Tables are presented in the same manner. We do not report the results for a quadratic term of ethnic heterogeneity because it was not statistically significant throughout all the alternative regression models, implying that the non-linear impact of ethnic heterogeneity on healthcare utilization is weak (see full result in appendix).

Taken together, the results in Tables 2, 3 show that women living in heterogeneous ethnic societies underutilize healthcare during pregnancy and after delivery. Specifically, the results in Table 2 of Panel A show that a unit increase in ethnic heterogeneity reduces the probability of delivery at a health facility birth, seeking antenatal care at the health facility, completion of child vaccination, and seeking postnatal healthcare from healthcare professional by about 10.5 percentage point, 21.9 percentage point, 28.5 percentage point, and 14.4 percentage point, respectively. The results for both Panels B and C of Table 2 are consistent with those of Panel A in terms of signs and significant levels but their magnitude changes. For example, the results for Panel C show that a unit increase in ethnic diversity lowers the probability of delivery at a health facility birth, seeking antenatal care at a health facility, completion of child vaccination, and seeking postnatal healthcare from a healthcare professional by about 18.9 percentage point, 19.0 percentage point, 17.0 percentage point, and 18.4 percentage point, respectively. Although the size of the effect differs across the three different surveys, we find a consistent negative relationship between ethnic diversity and healthcare utilization across all the three different surveys.

Table 3 reports results for the impact of ethnic diversity on healthcare utilization with a standard set of covariates. The reason behind utilizing this set of covariates is to help isolate the effect of ethnic diversity on healthcare utilization. Indeed, after estimating Eq. (4) with the control variables, we observed a decrease in the coefficients of ethnic heterogeneity compared to those in Table 2. For instance, the estimates in panel A of Table 3 reveal that a unit increase in ethnic heterogeneity reduces the probability of delivery at a health facility birth, seeking antenatal care at a health facility, completion of child vaccination, and seeking postnatal healthcare from healthcare professional by about 6.2 percentage point (versus 10.5 percentage point in Table 2), 5.4 percentage point (versus 21.9 percentage point in Table 2), 8.8 percentage point (versus 28.5 percentage point in Table 2), and 9.8 percentage point (versus 14.4 percentage point in Table 2), respectively. This suggests that controlling relevant variables that correlate with healthcare utilization is important. This is because the absence of control variables in the baseline estimates in Table 2 biased the results upwardly.

6.1 Mechanism

As already discussed in section 2, one key factor that is expected to mediate the relationship between ethnic heterogeneity and healthcare utilization is poverty. In this section, we follow previous studies and utilize the two-step approach to test whether poverty mediates the relationship between ethnic diversity and healthcare utilization (Koomson et al., 2020, Munyanyi & Churchill, 2022, Appau et al., 2020, Churchill & Smyth, 2017). For poverty to mediate the relationship between healthcare utilization and ethnic diversity, it must first correlate with healthcare utilization. We test the first stage by estimating the effect of poverty on healthcare utilization. The results are reported in both Table 4. Overall, the results in Table 5 show that poverty is associated with low healthcare utilization. For example, the results in Panel A Table 4 shows that one standard deviation increase in household deprivation score (MPI index) is associated with about 9.1 percentage points, 8.4 percentage points, 9.5 percentage point, and 11.4 percentage point decrease in delivery at health facility birth, seeking antenatal care at the health facility, completion of child vaccination, and seeking for postnatal healthcare from a healthcare professional, respectively.

In the second step, if poverty acts as a mediator for the link between ethnic diversity and healthcare utilization, then after including it as an additional control variable in our regression model, the coefficient of ethnic heterogeneity is expected to decrease in magnitude or render it statistically insignificant using the baseline estimates as a reference. Once the coefficient becomes smaller or statistically insignificant, it is expected the R-square should also increase because the effect of ethnic diversity on healthcare utilization is partially explained. From the results reported in Table 5, it is observed that the magnitude of the coefficient of ethnic diversity decreases while the R-square increases significantly after controlling for poverty. This suggests that poverty is a channel through which ethnic heterogeneity transmits to underutilization of healthcare during pregnancy periods and after birth.

6.2 Robustness checks

In this section, we provide two robustness checks for the baseline results. First, we utilize an alternative measure of ethnic heterogeneity that shows the conflict dimension of heterogeneous ethnic groups based on the distance between ethnic groups. Thus, in the results presented in Table 6, we measure diversity with ethnic polarization following Montalvo & Reynal–Querol (2005) and Awaworyi Churchill & Danquah (2022). Generally, the estimates show a unit increase in heterogeneous ethnic groups is more likely to lower the utilization of antenatal and postnatal healthcare. Thus, the results in Table 6 show a negative relationship between ethnic diversity and healthcare utilization which is consistent with the baseline results.

In Table 11 (See appendix), we examine the robustness of our results to an instrumental variable strategy. Specifically, Table 11 in appendix reports the two-stage least square (2SLS) estimates for the impact of ethnic heterogeneity on healthcare utilization employing regional-level ethnic diversity computed from older census as an instrument. The first-stage results reported in Table 11 show a positive relationship between the district-level ethnic heterogeneity and the regional-level ethnic heterogeneity. Also, the F-statistics reported in all columns are higher than 10, suggesting that the regional level ethnic diversity is strongly correlated with the district level of ethnic heterogeneity. The positive impact of the instrument on ethnic diversity conforms with existing studies providing empirical evidence to back the relevance of the instrument (Koomson et al., 2022, Awaworyi Churchill et al., 2019). Generally, the instrumental results are consistent with the baseline estimates in terms of the direction of the effect. Thus, the instrumental estimates confirm the negative impact of ethnic heterogeneity on healthcare utilization. For example, the results in Panel A of Table 11 show that a unit increase in ethnic diversity lowers the probability of delivery at a health facility birth, seeking antenatal care at the health facility, completion of child vaccination, and seeking postnatal healthcare from healthcare professional by about 29.9 percentage point, 27.3 percentage point, 28.6 percentage point, and 20.8 percentage point, respectively.

Our final robustness check is based on Lewbel’s two-stage least square approach. The intuition behind utilizing this approach is that our external instrument is to increase the precision of our external instrument. Thus, we utilized the Lewbel two-stage least square which combines both internal and external instruments to increase the predictive power of our instrument. Table 12 in appendix reports the results for the Lewbel 2SLS approach drawn from a regression that combines both internally generated instruments and the external. Generally, the results show that a unit increase in heterogeneous ethnic groups lowers the likelihood of utilizing antenatal and postnatal healthcare. These results are robust to the baseline estimates in Table 3, given that the signs of the coefficient do not change but only the magnitude changes after using a different estimation approach.

7 Conclusion and policy recommendations

One of the main goals of the Sustainable Development Global Goals is to decrease maternal mortality to 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 births by 2030. One of the potential means to achieve this is to increase healthcare utilization among women during pregnancy and soon after delivery. However, increasing the utilization of healthcare requires better insight into factors that influence it. As a result, numerous studies have been undertaken to examine the determinants of healthcare utilization in many developing countries (Agyemang-Duah et al., 2021, Agyemang-Duah et al., 2019, Paine et al., 2018), but no study has examined the impact of ethnic heterogeneity on healthcare utilization during pregnancy and soon after delivery. This paper attempts to bridge this literature gap by examining the effect of ethnic diversity on antenatal and postnatal healthcare utilization. Most importantly, it also examines whether poverty mediates the relationship between health utilization and ethnic diversity. Overall, two main findings emerged from this study. First, we find that ethnic diversity reduces healthcare utilization during pregnancy and after delivery. Second, we also find that poverty acts as a mechanism of change for the impact of ethnic heterogeneity on healthcare utilization.

The findings from this study are very important because they provide a new perspective on factors worth considering when devising policies aimed at increasing healthcare utilization during pregnancy and after delivery. In this era, most countries are ethnically diverse, and this presents significant implications at various levels for economic progress, especially for developing countries like Ghana with high diverse ethnic societies. Specifically, most societies in developing countries are ethnically diverse which presents significant implications for healthcare utilization. This study demonstrates that in addition to achieving universal health insurance coverage and reducing costs associated with healthcare, sociocultural factors such as ethnic diversity have an important role in explaining healthcare utilization and thus should be considered when policy makers are devising policies.

Also, given the mediating role of poverty, poverty reduction strategies must be implemented in societies that are highly ethnically diverse. Such poverty reduction strategies may include but are not limited to providing free maternal healthcare delivery, financial aid, and antenatal care and building more community-based healthcare facilities in ethnically diverse societies. All these may contribute to poverty reduction which, in turn, increase healthcare utilization.

References

Addai, I., & Pokimica, J. (2010). Ethnicity and economic well-being: The case of Ghana. Social Indicators Research, 99, 487–510.

Agyemang-Duah, W., Adei, D., Oduro Appiah, J., Peprah, P., Fordjour, A. A., Peprah, V., & Peprah, C. (2021). Communication barriers to formal healthcare utilisation and associated factors among poor older people in Ghana. Journal of Communication in Healthcare, 14, 216–224.

Agyemang-Duah, W., Mensah, C. M., Peprah, P., Arthur, F., & Abalo, E. M. (2019). Facilitators of and barriers to the use of healthcare services from a user and provider perspective in Ejisu-Juaben municipality, Ghana. Journal of Public Health, 27, 133–142.

Akay, A., Constant, A., Giulietti, C., & Guzi, M. (2017). Ethnic diversity and well-being. Journal of Population Economics, 30, 265–306.

Alcalá, H. E., & Cook, D. M. (2018). Racial discrimination in health care and utilization of health care: a cross-sectional study of California adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33, 1760–1767.

Alesina, A., Baqir, R., & Easterly, W. (1999). Public goods and ethnic divisions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, 1243–1284.

Alesina, A., Devleeschauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth, 8, 155–194.

Alesina, A., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2011). Segregation and the quality of government in a cross section of countries. American Economic Review, 101, 1872–1911.

Alhassan, R. K., Nketiah-Amponsah, E., Ayanore, M. A., Afaya, A., Salia, S. M., Milipaak, J., ANSAH, E. K., & Owusu-Agyei, S. (2019). Impact of a bottom-up community engagement intervention on maternal and child health services utilization in Ghana: a cluster randomised trial. BMC Public Health, 19, 1–11.

Alkire, S. & Santos, M. E. 2010. Acute multidimensional poverty: a new index for developing countries.

Ansah, G.N. (2014) Re-examining the fluctuations in languages in-education policies in post independence Ghana. Multilingual Education, 4, 1–15.

Anafi, P., Mprah, W. K., Jackson, A. M., Jacobson, J. J., Torres, C. M., Crow, B. M., & O’rourke, K. M. (2018). Implementation of fee-free maternal health-care policy in Ghana: perspectives of users of antenatal and delivery care services from public health-care facilities in Accra. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 38, 259–267.

Anyidoho, A., & Dakubu, M. E. K. (2008). Ghana: Indigenous languages, English, and an emerging national identity. Language and National Identity in Africa, 141, 157.

Appau, S., Awaworyi churchill, S., & Farrell, L. 2020. Wellbeing among older people: an introduction. Measuring, understanding and improving wellbeing among older people. Springer.

Apt, N. 2013. Older people in rural Ghana: health and health seeking behaviours. Aging and health in Africa. Springer.

Arthur, E. (2012). Wealth and antenatal care use: implications for maternal health care utilisation in Ghana. Health Economics Review, 2, 1–8.

Awaworyi Churchill, S., & Danquah, M. (2022). Ethnic diversity and informal work in Ghana. The Journal of Development Studies, 58, 1–20.

Awaworyi Churchill, S., & Farrell, L. (2020). Australia’s gambling epidemic: The role of neighbourhood ethnic diversity. Journal of Gambling Studies, 36, 97–118.

Awaworyi Churchill, S., Farrell, L., & Smyth, R. (2019). Neighbourhood ethnic diversity and mental health in Australia. Health Economics, 28, 1075–1087.

Awaworyi Churchill, S., & Mishra, V. (2017). Trust, social networks and subjective wellbeing in China. Social Indicators Research, 132, 313–339.

Baker JR, E. L., Potter, M. A., Jones, D. L., Mercer, S. L., Cioffi, J. P., Green, L. W., Halverson, P. K., Lichtveld, M. Y., & Fleming, D. W. (2005). The public health infrastructure and our nation’s health. Annu. Rev. Public Health, 26, 303–318.

Barnes-Mauthe, M., Arita, S., Allen, S. D., Gray, S. A. & Leung, P. (2013). The influence of ethnic diversity on social network structure in a common-pool resource system: implications for collaborative management. Ecology and Society, 18.

Becker, G. S. (2010). The economics of discrimination, University of Chicago press.

Bleaney, M., & Dimico, A. (2017). Ethnic diversity and conflict. Journal of Institutional Economics, 13, 357–378.

Bodomo, A. B. (1996). On language and development in. Africa: The case of Ghana. Nordic journal of African studies,, 5, 21–21.

Bulatao, R. A., & Ross, J. A. (2003). Which health services reduce maternal mortality? Evidence from ratings of maternal health services. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 8, 710–721.

Chazan, N. (1982). Ethnicity and politics in Ghana. Political Science Quarterly, 97, 461–485.

Churchill, S. A., & Smyth, R. (2017). Ethnic diversity and poverty. World Development, 95, 285–302.

Dincer, O. C. (2011). Ethnic diversity and trust. Contemporary Economic Policy, 29, 284–293.

Dionne, K. Y. (2015). Social networks, ethnic diversity, and cooperative behavior in rural Malawi. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 27, 522–543.

Fearon, J. D. (2003). Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. Journal of economic growth, 8, 195–222.

Frank, J. W., Wang, E. A., Nunez-Smith, M., Lee, H., & Comfort, M. (2014). Discrimination based on criminal record and healthcare utilization among men recently released from prison: a descriptive study. Health & justice, 2, 1–8.

Gereke, J., Schaub, M., & Baldassarri, D. (2018). Ethnic diversity, poverty and social trust in Germany: Evidence from a behavioral measure of trust. PloS one, 13, e0199834.

Gradín, C., Del Río, C., & Cantó, O. (2010). Gender wage discrimination and poverty in the EU. Feminist Economics, 16, 73–109.

Grand-Guillaume-Perrenoud, J. A., Origlia, P., & Cignacco, E. (2022). Barriers and facilitators of maternal healthcare utilisation in the perinatal period among women with social disadvantage: A theory-guided systematic review. Midwifery, 105, 103237.

Greenberg, J. H. (1956). The measurement of linguistic diversity. Language, 32, 109–115.

Gyasi, R. M., Adam, A. M., & Phillips, D. R. (2019). Financial inclusion, Health-Seeking behavior, and health outcomes among older adults in Ghana. Research on aging, 41, 794–820.

Harris, M. B. (1996). Aggression, gender, and ethnicity. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 1, 123–146.

Haruna, U., Dandeebo, G. & Galaa, S. Z. 2019. Improving access and utilization of maternal healthcare services through focused antenatal care in rural Ghana: a qualitative study. Advances in Public Health, 2019, 1–12.

Hossen, A., & Westhues, A. (2010). A socially excluded space: restrictions on access to health care for older women in rural Bangladesh. Qualitative health research, 20, 1192–1201.

Kanbur, R., Rajaram, P. K., & Varshney, A. (2011). Ethnic diversity and ethnic strife. An interdisciplinary perspective. World Development,, 39, 147–158.

Kim, H.-K., & Lee, M. (2016). Factors associated with health services utilization between the years 2010 and 2012 in Korea: using Andersen’s behavioral model. Osong public health and research perspectives, 7, 18–25.

Koomson, I., Afoakwah, C. & Ampofo, A. (2022). How does ethnic diversity affect energy poverty? Insights from South Africa. Energy Economics, 106079.

Koomson, I., & Churchill, S. A. (2021). Ethnic diversity and food insecurity: Evidence from Ghana. The Journal of Development Studies, 57, 1912–1926.

Koomson, I., Villano, R. A., & Hadley, D. (2020). Effect of financial inclusion on poverty and vulnerability to poverty: Evidence using a multidimensional measure of financial inclusion. Social Indicators Research, 149, 613–639.

Lewbel, A. (2012). Using heteroscedasticity to identify and estimate mismeasured and endogenous regressor models. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 30, 67–80.

Magadi, M. A., Madise, N. J., & Rodrigues, R. N. (2000). Frequency and timing of antenatal care in Kenya: explaining the variations between women of different communities. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 551–561.

Mcnamee, P., Ternent, L., & Hussein, J. (2009). Barriers in accessing maternal healthcare: evidence from low-and middle-income countries. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 9, 41–48.

Miguel, E. (2006). Ethnic diversity and poverty reduction. Understanding poverty, 169–184.

Miguel, E., & Gugerty, M. K. (2005). Ethnic diversity, social sanctions, and public goods in Kenya. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 2325–2368.

Montalvo, J. G., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2005). Ethnic polarization, potential conflict, and civil wars. American Economic Review, 95, 796–816.

Munyanyi, M. E., & Churchill, S. A. (2022). Foreign aid and energy poverty: Sub-national evidence from Senegal. Energy Economics, 108, 105899.

Novignon, J., Ofori, B., Tabiri, K. G., & Pulok, M. H. (2019). Socioeconomic inequalities in maternal health care utilization in Ghana. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18, 1–11.

Nuamah, G. B., Agyei-Baffour, P., Mensah, K. A., Boateng, D., Quansah, D. Y., Dobin, D., & Addai-Donkor, K. (2019). Access and utilization of maternal healthcare in a rural district in the forest belt of Ghana. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19, 1–11.

Organization, W. H. (2002). WHO antenatal care randomized trial: manual for the implementation of the new model. World Health Organization.

Owen, M. D., Colburn, E., Tetteh, C., & Srofenyoh, E. K. (2020). Postnatal care education in health facilities in Accra, Ghana: perspectives of mothers and providers. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20, 1–10.

Paine, S.-J., Harris, R., Stanley, J., & Cormack, D. (2018). Caregiver experiences of racism and child healthcare utilisation: cross-sectional analysis from New Zealand. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 103, 873–879.

Parmar, D., Williams, G., Dkhimi, F., Ndiaye, A., Asante, F. A., Arhinful, D. K., & Mladovsky, P. (2014). Enrolment of older people in social health protection programs in West Africa–does social exclusion play a part? Social Science & Medicine, 119, 36–44.

Patra, S., Mishra, P., Mahapatra, S., & Mithun, S. (2016). Modelling impacts of chemical fertilizer on agricultural production: a case study on Hooghly district, West Bengal, India. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 2, 1–11.

Ravensbergen, W., Drewes, Y., Hilderink, H., Verschuuren, M., Gussekloo, J., & Vonk, R. (2019). Combined impact of future trends on healthcare utilisation of older people: a Delphi study. Health Policy, 123, 947–954.

Robinson, A. L. (2020). Ethnic diversity, segregation and ethnocentric trust in Africa. British Journal of Political Science, 50, 217–239.

Sefa-Nyarko, C. (2021). Ethnicity in electoral politics in Ghana: colonial legacies and the constitution as determinants. Critical Sociology, 47, 299–315.

Service, G. S. (2013). 2010 Population & Housing Census Report: District Analytical Report:[name of District Or Municipal Assembly], Ghana Statistical Service.

Sturgis, P., Brunton-Smith, I., Read, S., & Allum, N. (2011). Does ethnic diversity erode trust? Putnam’s ‘hunkering down’thesis reconsidered. British Journal of Political Science, 41, 57–82.

Tian, S., Yang, W., Le Grange, J. M., Wang, P., Huang, W., & Ye, Z. (2019). Smart healthcare: making medical care more intelligent. Global Health Journal, 3, 62–65.

Acknowledgements

This paper benefited from the insightful and constructive comments of the editor (Professor Hope Corman) and anonymous reviewers. We thank them for their time, and effort.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.A.: conceptualisation, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, resources, writing—original draft and editing. E.K.A.: methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adabor, O., Ayesu, E.K. Ethnic heterogeneity and healthcare utilization: The mediating role of poverty in Ghana. Rev Econ Household (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-024-09695-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-024-09695-9