Abstract

Recent analyses have shown that commutes to and from work are not symmetric, suggesting that intermediate activities are at the root of the asymmetries. However, to model how these activities accumulate and interact within trips to and from work is a methodologically unexplored issue. We analyze the intermediate activities done while commuting, using data from the American Time Use Survey for the period 2003–2019. We show that commuting as defined in Time Use Surveys is underestimated, with significant differences that depend on whether intermediate activities are considered. Such differences are especially important in commuting from work to home and reveal gender differences. Our results contribute to the analysis of commuting behavior by proposing new identification strategies based on intermediate non-trip episodes, and by showing how commuting interacts with other non-commuting activities. We also explore intermediate episodes during commuting, which may partially explain gender differences in commuting time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The time spent commuting to work and back again has been considered symmetric in most studies, but recent evidence has shown that commutes are not equal, which has implications on theoretical, methodological, and policy grounds (Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2021). Intermediate activities - that is, activities that occur within the trips to and from work - may drive such asymmetries, but little or no evidence has been shown to date. The analysis of how activities accumulate within trips to and from work is methodologically important, as it may help to explain gender differences in commuting times. If mothers, who are normally in charge of household responsibilities (Gimenez-Nadal & Molina, 2016), go to pick up their children from school on their return trip from work, they may report that as travel related to childcare and not as a return from work, although it may still be exactly that. If this travel is considered as commuting, perhaps the previously reported gender differences in commuting time (Gimenez-Nadal & Molina, 2016; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2022) would decrease, disappear, or even reverse.

The analysis of intermediate activities has implications at the methodological level. Several authors have used Time Use Surveys (TUS) to analyze the commuting behavior of workers (Gimenez-Nadal & Molina, 2016; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2018a, 2018b, 2020), given the rich information that TUS provide. But TUS generally identify commuting episodes as trips to work and from work, based on respondents’ perceptions, but not based on the initial and final location. Following the previous example, if a given individual drives their child to school and then commutes to work, the first travel behavior (from home to the child’s school) is not identified as commuting to work but as a trip related to childcare. Furthermore, non-trip activities done while commuting (i.e., intermediate activities) should not be considered as part of the commute. How this identification affects the analysis of commuting times has barely been analyzed (Kimbrough, 2019).

Within this framework, this paper explores commuting times, with a focus on the intermediate activities done while commuting, using data from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) for the period 2003–2019. We differentiate among the identification of commutes, computed commutes (all trip episodes from home to work, and from work to home), and “bulk” commutes (i.e., computed commutes and intermediate activities done while commuting). We also address potential differences between commutes to work and commutes from work (Coria & Zhang, 2015; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2021), differences in male and female workers’ commuting (Gimenez-Nadal & Molina, 2016), and show how intermediate activities partially explain such differences. We find that the computed time of commuting is about 15.0 min longer than the TUS lexicon time, while commuting bulk time is about 18.7 minutes longer than the computed time, excluding intermediate activities. Furthermore, the three definitions seem to be correlated differentially to worker characteristics, indicating that the specific definition of commuting is crucial. Contrarily, the relationships between commuting and metropolitan forms do not appear to be affected. Our results reveal asymmetries in intermediate activities, driven by leisure and shopping activities, which are concentrated while commuting from work, rather than while commuting to work. Regarding gender differences in commuting times and intermediate activities, we find that the differences are sensitive to the definition of commuting.

From a methodological perspective, we contribute to the literature by showing that TUS lexicons tend to underestimate the time spent by workers commuting to/from work, as 24.5% of the time travelling from home (work) to work (home) is not identified as commuting. The inclusion of intermediate activities has a further impact on the estimation of commuting times. The correlation between commuting time and worker characteristics is sensitive to the definition of commuting, so different identifications of commuting are likely to lead to different research results and conclusions. We report asymmetries in commuting times that depend on the definition of commuting, and also in intermediate activities while commuting. Workers tend to do more intermediate activities while commuting from work, than while commuting to work, and thus analyses of worker daily activities should carefully consider these activities, either as intermediate activities or as part of commuting behaviors.

Furthermore, the previously reported gender gap in commuting time is sensitive to the definition of commuting. Women spend more time than men doing intermediate activities while commuting from work, which compensates for their shorter commuting times, and then the overall difference in the time spent going from work between women and men becomes non-significant. However, men still spend more time commuting to work than do women, even when intermediate activities are considered.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the ATUS data and variables, and the various definitions of commuting time. Section 3 shows differences in commuting times, how the times correlate with worker characteristics, and the main intermediate activities done while commuting. Section 4 studies gender differences in commuting times and intermediate activities, to and from work. Section 5 concludes.

2 Data and variables

We use data from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) for the period 2003–2019. The ATUS data provides us with socio-economic variables about respondents, but also information on individual time use based on diaries, where respondents report their activities during the 24 hours of the day, from 4 am to 4 am of the next day. The advantage of 24-hour self-reported diary data over other types of survey based on stylized questionnaires, is that diaries produce more reliable and accurate estimates (Bonke, 2005; Yee-Kan, 2008). The ATUS is considered the official time use survey of the US, it is sponsored by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and conducted as part of the Current Population Survey (CPS) by the US Census Bureau. Furthermore, the ATUS data is included as part of the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) of the Institute for Social Research and Data Innovation of the University of Minnesota (Hofferth et al., 2020).Footnote 1

Information in diaries is coded according to the ATUS activity-coding procedures, which classify respondents’ activities in a range of categories, namely personal care, household activities, caring, work activities, education, consumer purchases, professional and household services, government and civic obligations, eating and drinking, leisure, sports and recreation, religious activities, volunteer activities, calls, and travel. The diaries include other useful information, such as where and with whom activities are done, which allows us to distinguish between activities done at home and at the workplace, and the mode of transport of trip episodes.

We restrict the ATUS sample to employed individuals between 16 and 65 years old, who worked the diary day, and whose diary day was not conducted during “strange” days (self-reported), to avoid potential bias arising from atypical daily behaviors. Furthermore, we follow Gimenez-Nadal et al. (2018a, 2018b, 2021), and retain respondents who spent more than 60 min working during the diary day. Since we are interested in studying commuting behaviors and the time spent in intermediate activities while commuting, we omit from the baseline sample those employees or self-employed workers who do not commute to/from work (i.e., teleworkers or telecommuters), although the conclusions are robust to including telecommuters.Footnote 2 We discard observations that can be considered outliers in multivariate data, using Billor et al. (2000) blocked adaptive computationally efficient outlier nominators (BACON) algorithm. These restrictions leave a sample of 42,682 commuters, of whom 21,860 are men and 20,822 are women. Furthermore, 34,058 of the respondents filled in their diaries during weekdays, with the remaining 8624 workers filling the diaries in during the weekend.

Socio-demographic information of respondents can be obtained from the ATUS, containing information on respondent’s gender, age, race, US citizenship status, Hispanic origin, education level, living in couple, the labor status of the couple, family size and number of children, the age of the youngest child, and housing attributes (tenure and housing unit).Footnote 3 Economic and labor information is also collected in the ATUS, and we define variables for household annual income (reported in income brackets), weekly working hours, type of worker (private sector, public sector, self-employed), full/part-time status, and occupation.Footnote 4 The ATUS data includes certain variables collecting geographic and metropolitan information on respondents, such as the State of residence, the size of the MSA, and whether respondents reside in metropolitan center areas, metropolitan fringe areas, or non-metropolitan areas.Footnote 5 The ATUS also includes information on respondents’ type of housing unit, and we define a dummy variable that takes value 1 for respondents living in a house/apartment/flat (0 otherwise).

All the socio-demographic and metropolitan variables have been found to be correlated with workers’ commuting, and thus we consider them in the empirical analysis; summary statistics for these variables are shown in Table 8 of the Appendix; Table 10 in Appendix B shows similar summary statistics when telecommuters are included in the sample.

Commuting time is identified in the ATUS with the code 180501 (“commuting to/from work”) and represents travel episodes to/from work. Several authors have analyzed commuting times using this code (see Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2021 for a review). One limitation of TUS is that, as highlighted by Kimbrough (2019), extracting trip behaviors from the survey may imply some degree of measurement error, as the surveys do not consider activities done during commuting, such as stops for shopping, for taking kids to or from school, or for using services, among others. Thus, part of commuting trips may be coded not as commuting but as another kind of trip related to secondary activities. Prior research has questioned whether these intermediate activities should be considered as part of commuting trips, or not (Horner, 2004; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2021), and results are sensitive to the definition of commuting.

To analyze how the time devoted to commuting varies with the consideration of intermediate activities, we use two alternative definitions of commuting time, following Gimenez-Nadal et al. (2021) and taking into account the place where trips begin and end. We first consider that every trip episode, or combination of episodes, that begins at home and ends at work (or vice versa) is a commuting trip, regardless of whether those trip episodes are defined as “commuting to/from work” in the ATUS lexicon (Commuting and intermediate trips). In the following series of episodes: (1) any activity at respondents’ home; (2) trip episode; (3) grocery shopping; (4) trip episode; (5) using service; (6) trip episode; (7) paid work at respondent’s workplace, regardless of whether the ATUS lexicon identifies episodes (2), (4), and (6) as commutes or other type of trips, we identify the three travel episodes as commuting to work. Similarly, consider the following series of episodes: (1) Paid work at respondents’ workplace; (2) trip episode; (3) picking up child from school; (4) trip episode; (5) any activity at respondents’ home. We identify episodes (2) and (4) as commuting episodes, regardless of whether they are coded as commuting in the ATUS lexicon. Thus, our definition of commuting times (i.e., Commuting and intermediate trips) is expected to differ from Commuting ATUS.

To define the Commuting and intermediate trips variable, we make sure that the same trip episode is not identified as commuting, either to or from work. We make sure that no intermediate activity is done at respondents’ home or workplace. For example, consider the following series of episodes: (1) Any activity at respondent’s home; (2) trip episode; (3) any activity not at home; (4) trip episode; (5) any activity at respondent’s home; (6) trip episode; (7) paid work at respondent’s workplace. Our identification of commuting episodes excludes trip episodes (2) and (4) from the definition of commuting, and in this example only trip episode (6) would be identified as commuting.

We define Bulk commuting as the time that passes from when the worker leaves his home/work until he arrives at his work/home. This definition includes both commuting, and trip and non-trip intermediate activities, and is the less restrictive definition of commuting.

Given that the variables Commuting and intermediate trips and Bulk commuting include non-commuting activities while commuting to/from work, we follow prior research (Aguiar & Hurst, 2007, 2009; Guryan et al., 2008; Gimenez-Nadal & Sevilla, 2011, 2012) and compute the total time workers spend in intermediate activities in the following categories: paid work, leisure, childcare, unpaid work, purchasing products, using services, and personal care.

3 Differences by the definition of commuting

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the three measures of commuting time over the analyzed period, measured in minutes per day: Commuting ATUS, Commuting and intermediate trips, and Bulk commuting, leading to three takeaways. (Fig. 5 in Appendix B shows a similar figure including telecommuters in the sample.) First, all three measures of commuting display a slightly increased trend over the last two decades, with linear trends around 0.04. The increase in commuting time over the analyzed period in the US is consistent with prior studies (Kirby & LeSage, 2009; McKenzie & Rapino, 2009; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2018a; Burd et al., 2021). Second, Commuting ATUS gives the lowest values of commuting time, which may indicate that commuting time based on TUS activity codes may be underestimating commuting times. For the analyzed period the time devoted to Commuting and intermediate trips is about 15 min longer in comparison to Commuting ATUS. Third, the time devoted to Bulk commuting is about 19 min longer than the time devoted to Commuting and intermediate trips for the analyzed years. Hence, Fig. 1 shows that TUS lexicons tend to produce shorter commuting times than those computed in terms of origin and destination of trips (Kimbrough, 2019; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2021), and that commuting times are sensitive to the inclusion of intermediate activities in the definition of commuting (Horner, 2004; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2021).

The evolution of commuting time. Note: The sample (ATUS 2003–2019) is restricted to employees who worked the diary day. Telecommuters are excluded. Commuting is measured in minutes per day. Commuting ATUS includes commuting episodes only. Commuting and intermediate trips includes all the intermediate trip activities. Bulk commuting includes trip and non-trip intermediate activities

Table 1 shows the average time spent commuting by workers for the three definitions of commuting. The average time devoted to Commuting ATUS is 46.07 min per day (40.98 min per day when telecommuters are considered), while the average time devoted to Commuting and intermediate trips is 61.03 (54.29) minutes per day. This means that about 24.51% of the travel that elapses between home/work and work/home is not captured by the TUS lexicon. The average time devoted to Bulk commuting is about 79.73 (70.92) minutes per day, indicating that intermediate non-trip activities represent, on average, 30.64% of the time spent commuting to/from work. The differences between the three commuting time definitions are statistically significant at standard levels (p < 0.01).Footnote 6 The figures obtained from Commuting and intermediate trips are closer to other official statistics for the US, such as the American Community Survey, according to which one-way commutes last about 27.6 min per day (Burd et al., 2021).

Figure 2 shows the map of commuting time in the US, by State, representing both Commuting and intermediate trips and Bulk commuting. Despite the difference in the average time spent in commuting, the areas with relatively higher average time in Commuting and intermediate trips are the same areas where the time devoted to Bulk commuting is also higher. This suggests that, even when research results may be sensitive to the definition of commuting, there is some degree of spatial correlation and then studies of commuting, urban forms, regions, and metropolitan characteristics may not suffer from such sensitivity.

The map of average commuting time, by state. Note: The sample (ATUS 2003–2019) is restricted to employees who worked the diary day. Telecommuters are excluded. Commuting is measured in minutes per day. Commuting time represents commuting and intermediate trips, and is classified in six groups in terms of quantiles. Bulk commuting varies from 58.26 to 109.34 min per day, and symbol sizes are proportional to average state bulk commuting values. Alaska and Hawaii are omitted from the map for the sake of legibility

3.1 The correlates of commuting time

Given that differences in commuting times are quantitatively meaningful, we now analyze whether the differences across alternative definitions of commuting time, in terms of how they relate to worker characteristics, have been linked to commuting behaviors in prior studies. In doing so, we regress the time spent commuting by workers, for each type of commuting (Commuting ATUS, Commuting and intermediate trips, Bulk commuting), in terms of socio-demographics (including respondents’ gender, age, age squared, race, US citizenship and Hispanic status, education, living in couple, the couple’s labor status, family size, number of children and age of the youngest child, tenure status, and the type of housing), labor and income variables (weekly usual work hours, the type of worker, private sector workers being the reference category, part-time status, and household income, metropolitan characteristics (living in a metropolitan center or metropolitan fringe area, with non-metropolitan areas being the reference category, and the population size of the MSA of residence). We also control for respondents’ means of commuting, occupation, year, and state fixed effects.Footnote 7 Estimates include sample weights, and robust standard errors.

Estimation results are shown in Table 2. Column (1) shows the main coefficients for Commuting ATUS, Column (2) shows the coefficients for Commuting and intermediate trips, and Column (3) shows estimates for Bulk commuting. (Table 11 in Appendix B shows estimation results when telecommuters are included in the sample.) Focusing first on worker socio-demographics, we observe that men spend more time commuting than women when no non-trip intermediate activities are considered, net of observed heterogeneity, although the coefficients are quantitatively different in Columns (1) and (2). According to Commuting ATUS, men commute about 5.9 more minutes per day than similar women, but the difference shrinks to 2.4 min when analyzing Commuting and intermediate trips. Column (3) shows that the commuting time gender gap becomes non-significant when intermediate activities are considered as part of commuting time (Bulk commuting).

The age of workers seems to be correlated similarly with commuting time, independently of the definition used for commuting, following an inverted U-shaped correlation, although statistical significance increases when Commuting and intermediate trips and Bulk commuting are studied, relative to Commuting ATUS. Results also show that white workers and US citizens commute fewer minutes per day than their counterparts. Respondents’ Hispanic origin, however, is not significant. University educated workers seem to commute similarly to their counterparts when commuting is measured by Commuting ATUS, but they commute longer times when measured by Commuting and intermediate trips, and Bulk commuting.Footnote 8 Household composition is also correlated differentially with commuting, suggesting that single individuals tend to spend more time doing intermediate activities than their non-single counterparts. This result could be explained by cohabiting individuals preferring scheduled joint time with their partners, rather than solo activities (Cosaert et al., 2023). Family size displays the same results as living in couple, as it is positively correlated with Commuting ATUS, uncorrelated with Commuting and intermediate trips, and negatively correlated with Bulk commuting. The labor status of the couple and the number of kids are only statistically significant when we study commuting times using Commuting ATUS. The age of the youngest kid, on the other hand, is not significant, and the type of tenure and housing unit does not differ across definitions of commuting time.

Focusing on the labor and income variables, household income categories are all not significant at standard levels. Despite this lack of statistical significance, coefficients suggest that higher income levels are positively correlated with commuting time (Zax, 1991; White, 1999; Ross & Zenou, 2008; Fu & Ross, 2013; Mulalic et al., 2014; Gutiérrez-i-Puigarnau et al., 2016; Ruppert et al., 2016; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2018b). Conversely, work hours, which have been found to be related to worker commuting behaviors (Gutiérrez-i-Puigarnau & van Ommeren, 2010), are significant when we use Commuting ATUS or Bulk commuting, while this variable is not significant at standard levels for Commuting and intermediate trips. Relative to private sector employees, public sector workers spend less time commuting, independently of the definition used. However, being a part-time worker is negatively related to commuting time, and self-employment is related to increased commuting time. Since prior research has documented that self-employed workers tend to commute for shorter times than employees, the evidence presented here indicates that prior results should be revised using alternative definitions of commuting time (van Ommeren & van der Straaten, 2008; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2018a, 2020). When we focus on the metropolitan characteristics of the area of residence of workers, results indicate that workers in densely populated areas spend more time commuting than their counterparts, robust to existing research (Hamilton, 1989; Kahn, 2000; Manning, 2003; Rodríguez, 2004; Gobillon et al., 2007; Connolly 2008; van Ommeren & van der Straaten, 2008; van Acker & Witlox, 2011; Gutiérrez-i-Puigarnau et al., 2016; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2020). Furthermore, residing in the center of a Metropolitan area is related to a decrease in commuting time. It then seems that, despite some quantitative differences, the correlation between commuting behaviors and urban or metropolitan forms does not crucially depend on the identification of commuting times.

An important note from Table 2 is that R-squared values are relatively low.Footnote 9 Van Ommeren and van der Straaten (2008) and Gimenez-Nadal et al. (2020) discuss this issue in detail and find that most of the empirical analyses of commuting times report quite low R-squared (below 0.10). However, we find that the R-squared numbers decrease when we analyze commuting time and intermediate activities, highlighting the complexity linked to worker commuting behaviors, as previously reported in other studies (e.g., Cropper & Gordon, 1991; Small & Song, 1992; Manning, 2003; Rodríguez, 2004; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2021).

3.2 Intermediate activities to and from work

Empirical evidence has shown that commuting time is not symmetrical, in the sense that commutes to work and from work differ in their duration (Giménez-Nadal et al., 2021). One possible explanation for this difference may reside in intermediate activities, as it may be well that workers do most of them during their trips back home, when they are not constrained by their work schedule.

Figure 3 shows the evolution of the time devoted to Commuting and intermediate trips and Bulk commuting during the analyzed period, distinguishing between trips to and from work. (Figure 6 in Appendix B shows similar trends including telecommuters.) We observe that, for both directions, the time devoted to Commuting and intermediate trips and Bulk commuting has slightly increased over the analyzed period, suggesting that the time spent in intermediate activities has remained relatively constant over the period 2003–2019. Furthermore, we observe that the difference between Commuting and intermediate trips and Bulk commuting is around 4 min per day to work, and around 14 min per day from work, indicating that workers do more non-trip intermediate activities during the trips back home.

The evolution of commuting to work and from work. Note: The sample (ATUS 2003–2019) is restricted to employees who worked the diary day. Telecommuters are excluded. Commuting is measured in minutes per day. Commuting and intermediate trips includes all the intermediate trip activities. Bulk commuting includes trip and non-trip intermediate activities

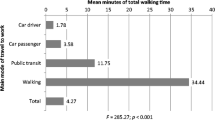

The prior evidence is confirmed in Table 3, showing the average time spent in Commuting and intermediate trips and Bulk commuting, in both the journeys to work and from work. It also shows the difference between Commuting and intermediate trips and Bulk commuting in both journeys. We observe that the average commuter worker spends 28.5 min commuting to work (or 25.4 min if telecommuters are considered), which increases to 32.5 (28.9) minutes when intermediate activities are considered. This means that the worker spends 4.0 (3.6) minutes doing intermediate activities while commuting to work, with this difference being statistically significant. The average time of commuting from work is 32.8 min (29.2 min if telecommuters are considered), vs 46.9 (41.7) minutes when intermediate activities are considered. Thus, workers spend 14.4 (12.5) more minutes in non-trip intermediate activities while commuting from work. The evidence indicates that most non-trip intermediate activities are concentrated in the trips back home; the average commuter spends 10.1 more minutes doing intermediate activities coming from work than going to work (9.0 more minutes if telecommuters are considered).

Table 4 shows the average times spent in leisure, childcare, unpaid work, personal care, purchasing goods, and using services while going to and from work. We also show the differences between the average time spent doing these activities, for the main sample excluding telecommuters, and for the sample including telecommuters. As previously reported, most of the time spent in these activities is concentrated coming from work. While going to work, commuters spend, on average, 0.88 min doing leisure, 0.62 min purchasing goods, 0.59 min doing childcare, 0.27 min using services, 0.14 min doing unpaid work, and 0.04 min in personal care. Workers spend 4.8 min doing leisure, 3.1 min purchasing goods, 0.87 min in childcare, 0.67 min using services, 0.53 min doing unpaid work, and 0.06 min in personal care, while commuting home. All the differences between the times spent doing these intermediate activities are statistically significant at standard levels (p < 0.01). The analogous magnitudes when telecommuters are included in the sample produce equivalent conclusions.

The results shown in Tables 3 and 4 are in line with the asymmetries in worker commuting behaviors described by Coria and Zhang (2015) and Gimenez-Nadal et al. (2021). Our results point to leisure and purchasing goods (shopping) as the most common activities done by workers while commuting and, specifically, while commuting from work to home.

3.3 Characterizing commuting trips and intermediate activities

We now characterize commuting trips, from and to work, according to the number of episodes, the percentage of each type of episode, and the duration of each episode. Given that ATUS collects time use information of respondents using diaries, we can select from diaries the commuting and trip and non-trip intermediate activities. Table 5 shows that trips to work, on average, contain 2.41 episodes, while the average number of trips from work is 2.88 episodes, with the difference being significant at standard levels (p < 0.01). Regarding the composition of trips to work, 85.7% of the episodes of these trips are commuting. The remaining episodes are composed mainly of childcare episodes (5.1%), purchasing goods episodes (3.4%), and leisure episodes (1.4%). On the other hand, for trips from work to home, 80.2% of the episodes are commuting, and the remaining 19.8% are episodes of purchasing goods (6.7%), leisure (3.4%), childcare (3.1%), unpaid work (1.1%), personal care (1.0%), using services (0.02%), and other type of activities (4.3%). All these differences are statistically significant at standard levels (p < 0.01).Footnote 10

Our results indicate that the average commuting episode to work lasts 17.99 min, vs.17.30 min for commutes from work. That is to say, although workers spend more time commuting from work than commuting to work – according to Bulk commuting–the episodes last longer when commuting to work. The difference in the duration of these episodes is significant at standard levels (p < 0.01). Table 5 also shows that asymmetries in commuting to and from work do not arise from the duration of commuting episodes, but from the composition of the trips. Regarding the rest of the activities, the average leisure episode to work lasts 0.56 min, vs. 2.54 min for the average leisure episode coming from work. Childcare episodes also last longer coming from work than going to work (0.46 vs. 0.37 min), and the same applies to personal care (0.36 vs. 0.17 min), unpaid work (0.28 vs. 0.09 min), purchases (1.6 vs 0.39 min), and services (0.03 vs. 0.02 min). All the differences between the time spent in these activities to and from work are significant at standard levels.

We now study what individual characteristics are related to the time spent doing intermediate activities while commuting to/from work, net of other worker characteristics.Footnote 11 To that end, we regress the time spent in intermediate activities while commuting to/from work, in terms of demographics, labor and income variables, metropolitan characteristics, occupation, year, and state fixed effects.Footnote 12 Given that the dependent variable may take value 0 for workers who do not do intermediate activities, Tobit models may be preferred. However, prior research has compared Tobit and OLS when studying time use, and results are similar (Frazis & Stewart, 2012; Gershuny, 2012; Foster & Kalenkoski, 2013). We then focus on OLS for the sake of simplicity.

Results are shown in Table 6. Column (1) shows intermediate activities to and from work, while Columns (2) and (3) focus on intermediate activities to work, and from work, respectively. (Results on the sample including telecommuters are shown in Table 12 in Appendix B; conclusions remain similar.) Estimates show that men in the sample spend about 2.4 fewer minutes per day in intermediate activities than do women, net of observable heterogeneity. Furthermore, this difference is concentrated in intermediate activities while commuting from work, as estimates show that all workers spend the same amount of time doing intermediate activities while commuting to work. Age, on the other hand, appears not to be correlated with the time spent in intermediate activities while commuting. There seems to be an inverted U-shaped correlation between age and the time spent in intermediate activities while commuting to work, although coefficients are statistically significant only at the 10% level.

Being white and being a US citizen are correlated with intermediate activity time in a statistically significant way. Specifically, white workers spend 1.8 more minutes per day in intermediate activities than non-whites, and US citizens spend 1.7 more minutes in intermediate activities than do immigrants. Both correlations are affected by intermediate activities while commuting from work, but not during commutes to work. Hispanic respondents spend 1.6 fewer minutes in intermediate activities than non-Hispanic respondents, but this correlation is significant only for commutes to work, and not for commutes from work.

Regarding education, those with secondary education spend about 2.2 more minutes per day in intermediate activities, although the difference from the reference education group (basic education only) is not significant at standard levels. However, the difference in the time in intermediate activities while commuting to work is 1.4 min, and significant at standard levels. The same difference while commuting from work is not statistically significant. Individuals with College education spend about 6.9 more minutes in intermediate activities than individuals with basic education only, and this difference corresponds to about 1.8 more minutes while commuting to work, and 5.1 more minutes while commuting from work (all the differences being highly significant). Thus, highly educated individuals spend more time in intermediate activities while commuting. Further research should analyze the composition of these intermediate activities, and potential differences by human capital, since education appears to be a main force underlying intermediate activities, regarding the estimated coefficients in Table 6.

Living in couple is correlated with decreased time in intermediate activities, since those who cohabit with a partner spend about 4.2 fewer minutes in intermediate activities while commuting than their single counterparts. Furthermore, most of that time (4.0 min) is concentrated in intermediate activities while commuting from work, with both coefficients being statistically significant. This result is consistent with two-member households coordinating to schedule joint activities at home, which is preferable to solo activities (Hallberg, 2003; Jenkins & Osberg, 2005; Hamermesh et al., 2008; Hamermesh, 2020; Cosaert et al., 2023), while single individuals have more incentives for solo activities. Similarly, family size is negatively related to the time spent in intermediate activities, with the difference being significant for trips to and from work. The number of kids, on the other hand, is associated with a small but statistically significant increased time in intermediate activities while going to work, possibly driven by taking the kids to school.

Regarding the labor and income variables, household income categories are all not statistically significant, although coefficients suggest a positive correlation with intermediate activities from work. Hours worked per week are positively correlated with the time in intermediate activities while commuting to work. Public sector employees spend less time in intermediate activities while commuting to work, but not from work. The self-employed spend, on average, 9.7 more minutes per day in intermediate activities while commuting, and 7.5 of those minutes are intermediate activities while commuting from work. Both coefficients are statistically significant, but differences with respect to employees commuting to work are not significant at standard levels. Part-time workers spend about 1.6 more minutes per day in intermediate activities while commuting to work, relative to similar full-time workers, but the difference between full- and part-time workers in intermediate activity time while commuting from work is not significant.Footnote 13

Interestingly, all the metropolitan variables included in the regressions are estimated to be not statistically significant at standard levels, which may indicate that the complex relationships reported by prior research between commutes and urban forms (Manning, 2003; Rodríguez, 2004; van Acker & Witlox, 2011; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2018a, 2020) are independent of the definition of commuting, and whether or not that definition excludes or includes intermediate activities should not affect conclusions.

3.4 Discussion and potential limitations

Some potential limitations and issues related to the definitions of commuting time that we propose emerge from the analysis. First, if we assign value zero to the variable Commuting to a worker because he/she did not commute to/from work during the diary day (i.e., worked from home that day), we also assign zero minutes to Commuting and intermediate trips, and to Bulk commuting, as there are no intermediate trips or intermediate activities. Thus, future research should focus on how telecommuting interacts with worker daily behaviors, as telecommuters have more time available for other activities (the time they save from commuting), although they cannot take advantage of commuting trips to do intermediate activities (e.g., they cannot stop in a grocery while commuting from work, and they need to go from home to the grocery, and back to home). This is an important dimension of worker daily behaviors that, to the best of our knowledge, has received little attention and should be addressed by further empirical research.

Second, the ATUS data (and other time-use data with information for diary days) does not allow us to analyze workers who are able to telecommute on some days, but who have to commute to the office on other days. The ATUS does not include information on this issue, and thus we consider a respondent to be a telecommuter if he/she did not commute to/from work during the diary day (even though he/she needs to commute to/from work on certain days not covered by the diary day). The analysis of this issue can be done in further research, using information on time allocations measured not through diary days, but from weekly diaries (e.g., as in time use surveys in Latin American countries).

Finally, a related concern is that our definition of Bulk commuting may affect how workers allocate their time after getting home. For example, some workers who work close to their home may avoid going directly home and shopping before going home and having dinner, resulting in more time in intermediate activities. Similarly, the worker who works close to his/her home may prefer to take the kids to school in the morning, then go back home, and then go to work. Conversely, workers who work far from home may prefer to go straight home after work, and then go shopping afterwards; or may prefer to take the kid to school in the morning and then go straight to work without returning to their home. In other words, we do not focus on how commuting times, and the time spent in intermediate activities, relate to other worker travel and non-travel behaviors, such as having dinner, or travelling before/after getting home for different purposes. To the best of our knowledge, this is an important dimension of worker time allocation and daily behavior that has received little attention, and further analyses should investigate such potential relationships.

4 The role of intermediate activities in the gender gap in commuting

Prior research has shown that there are gender differences in commuting time, with working men devoting more time to commuting than working women (White, 1986; Sandow, 2008; Sandow & Westin, 2010; Roberts et al., 2011; Dargay & Clark, 2012; McQuaid & Chen, 2012; Gimenez-Nadal & Molina, 2016; Le Barbanchon et al., 2021). However, existing analyses do not take into account the role that both trip and non-trip intermediate activities may have in shaping this difference. When we consider the complete sequence of activities of workers in their trips to and from work, the previously reported gap in commuting may expand, decrease, disappear, or even be reversed. We present the first analysis of how intermediate activities affect the gender gap in commuting. To that end, we look at gender differences in the time devoted to both Commuting and intermediate trips and Bulk commuting, we consider whether the trip is to or from work, and we analyze gender differences in leisure and shopping, given that those activities constitute the greater portion of intermediate activities (in terms of time devoted).

Table 7 shows the time spent commuting by male and female commuters in the sample. (Table 13 in Appendix B shows the magnitudes when including telecommuters in the sample.) According to Commuting and intermediate trips, women spend an average of 58.1 min per day commuting to/from work (51.7 min when telecommuters are considered), while men spend an average of 63.5 (56.4) minutes per day. This represents a gender difference in Commuting and intermediate trips of about 5.4 (4.7) minutes, which is statistically significant (p < 0.01). For Bulk commuting, women spend an average of 78.6 (70.0) minutes per day commuting to/from work while men spend an average of 80.7 (71.7) minutes per day commuting to/from work, with the difference being statistically significant (p < 0.01). However, these estimated differences are smaller than in prior studies (even when telecommuters are excluded), indicating that the gender gap in commuting time is sensitive to the inclusion of intermediate activities. Male commuters spend 17.20 min doing intermediate activities while commuting (15.3 min when telecommuters are considered), while women spend 20.5 (18.3) minutes in intermediate activities, which illustrates the smaller than-expected gender gap in commuting time.

Focusing on differences in commutes to and from work, results by gender show that most of the difference between women and men in the time spent in intermediate activities while commuting is concentrated in commuting from work. Women spend 27.4 (31.6) minutes commuting to work when intermediate activities are excluded (included), vs the 29.4 (33.9) minutes spent by men. That is to say, both men and women spend about 4 min doing intermediate activities while going to work, and the gender difference in these trips remains about 2 min per day, regardless of the identification of commuting. On commutes from work, the results show that the average female commuter spends 30.7 min in commuting trips, and another 16.3 min in intermediate activities, vs the 34.0 min spent by men commuting from work, and 12.8 min spent in intermediate activities. Thus, even when we find a gender difference in commuting times of about 3.3 min per day, which is significant at standard levels (p < 0.01), the difference becomes only 0.21 min per day - and is not statistically significant at standard levels - when intermediate activities are considered. (The conclusions derived from Table 13 including telecommuters are equivalent, although magnitudes are slightly smaller due to telecommuters reporting zero commuting times.)

The results are important for gender comparisons in commuting, since prior research has documented a large gender difference in commuting time. Our results show that this gender difference is smaller when intermediate activities are included. Furthermore, the bulk of this gender difference in concentrated on commuting from work, which normally occurs between 2 pm and 7 pm (Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2021). As a consequence, gender differences in commuting time should be revisited in light of our results. Our analysis also reveals that excluding or including telecommuters does not affect the main conclusions, so potential differences in the ability of women and men to telecommute seem not to drive the results.

We next analyze the intermediate activities at the root of the gender difference in commuting, and for simplicity, we focus on leisure and shopping episodes, given that these activities constitute the greater proportion of intermediate activities.Footnote 14 Table 7 shows that the average woman spends 0.78 min doing leisure while commuting to work, and 4.9 min while commuting from work. The difference of 4.2 min per day is statistically significant (p < 0.01). The average man spends 0.97 min doing leisure while commuting to work, and 4.7 min doing leisure while commuting from work. The difference for men accounts for 3.7 min per day and is also significant (p < 0.01). When comparing men and women, results show that men slightly surpass women in the time spent doing leisure while commuting to work, by 0.20 min per day, but this small difference is still significant (p < 0.05). However, the time spent in leisure while commuting from work does not appreciably differ between women and men at standard levels. Thus, it seems that intermediate leisure activities while commuting do not explain the overall commuting differences between women and men in terms of commuting trips and intermediate activities.

For the time spent shopping while commuting, we note that women (men) spend about 0.71 (0.55) minutes in these activities while commuting to work, and 4.4 (2.0) minutes when commuting from work. Specifically, women spend 2.3 more minutes per day than men in shopping as an intermediate activity while commuting from work. This difference accounts for 66.48% of the gender difference in intermediate activities when commuting from work, highlighting the importance of considering specific activities while commuting when analyzing gender differences. Again, results including telecommuters in the sample shown in Table 13 are similar, and the conclusions remain.

5 Conclusions

The time spent commuting to and from work has been considered symmetric in most studies, but recent evidence has shown that commutes are not symmetric, which has implications on theoretical, methodological, and policy grounds (Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2021). This paper contributes to the literature on commuting behavior by analyzing the time spent commuting and doing intermediate activities by workers in the US, using data from the American Time Use Survey for the period 2003–2019. We focus first on the identification of commuting in Time Use Surveys, identifying differences in the time use lexicon, computed commuting times, and computed times including intermediate activities. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first empirical exploration of the daily behaviors of workers focusing on what else workers do while commuting to and from work. The main finding of the paper is methodological, as we propose an alternative way to identify commuting episodes, and we contribute to the empirical base, since we report differences in commuting time definitions, asymmetries in commutes to and from work, and intermediate activities, and explore the individual attributes correlated with these intermediate activities.

The results report quantitative differences depending on the definition of commuting, as the computed time of commuting is about 24.5% longer than the TUS lexicon definition, whereas intermediate activities represent 30.6% of the time spent going from home to work and back. Furthermore, different definitions of commuting appear to be correlated differentially with worker characteristics, but not to urban forms. We also focus on the asymmetry of commuting behaviors and intermediate activities, and on gender differences. Results show that most of the intermediate activities done while commuting are concentrated during commuting from work to home, which has an impact on gender differences. Leisure activities, and activities related to shopping are the most common activities done while commuting from work, and this produces a non-statistically significant gender difference in bulk commuting times. Despite that, men still spend more time commuting to work, and the overall commuting time gender gap, measured in minutes per day, depends on the definition of commuting. We also study the characteristics related to time in intermediate activities, net of observed heterogeneity.

The paper has certain limitations. First, the ATUS is a cross-sectional database, and so we cannot estimate any causal relationships since results are subject to unobserved heterogeneity. Thus, all the results should be interpreted as conditional correlations. To date, no time use surveys are constructed as panel databases, and so this limitation cannot be addressed. Another limitation lies in the fact that we only consider the American Time Use Survey; future research should analyze different countries using national time use surveys, or data from the Multinational Time Use Study of the Centre for Time Use Research (Fisher et al., 2019). Furthermore, we focus only on commuting time, and we cannot include commuting distance as a main explanatory variable in the regression analysis. Therefore, the results may be affected by omission bias. Finally, the ATUS data does not include time-use information on secondary activities (i.e., activities done at the same time as the main activity). Thus, we cannot completely capture the intermediate activities, nor commuting times, and results should be interpreted as lower bounds for the actual times in both intermediate activities and commuting.

Despite these limitations, researchers and planners may consider the results to be of interest. From an academic point of view, it should be analyzed whether the negative consequences of commuting on worker outcomes (e.g., psychological well-being, health, productivity, etc.) remain robust to the definition of commuting. This represents a challenge, since surveys collecting commuting time from stylized questions (such as National Travel Surveys, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, the European Working Conditions Surveys, the British Household Panel Survey, and the German Socio-Economic Panel study) are limited in this task. On the other hand, planners and policymakers should consider our results in the design of transport policies. Commutes seem sensitive to intermediate activities, especially among commuters from work, not so much from commutes to work. This could be applied to public transport infrastructure, or road policies. For instance, if stops are more likely at certain hours, policies related to parking rates, or temporary traffic control policies could be adopted, depending on the city’s requirements. Public services and shops could also consider these results, as commuters seem more likely to stop and do chores while coming from work, rather than while going to work.

Further research should build on this work, as it opens doors for several contributions. In addition to studying commuting and intermediate activities using other time use databases, we report gender differences in commuting and intermediate activities. The genesis of these differences, including what activities drive them and how they contribute to individuals’ welfare, however, remains unexplored. For instance, it is unclear whether intermediate activities represent an increase in worker satisfaction or, conversely, those activities are not enjoyable, which could create intrahousehold inequalities. The impact of intermediate activities during extreme commuting behaviors should also be studied, as these activities should be especially important in longer commuting trips. The composition of intermediate activities while commuting, and differences in terms of human capital should also be studied, since the results indicate that having attended College or University is among the main determinants of the time spent in intermediate activities.

Notes

Information for the 2020 wave of the ATUS is available both in the US Bureau of Labor Statistics and in the IPUMS, but as the ATUS methodology was greatly affected by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the 2020 wave is not representative. See https://www.bls.gov/tus/covid19.htm#2 for more information. Note that while the ATUS has been conducted since 2003, it remains a cross-sectional database.

We follow existing applied research on worker commuting and delete workers reporting zero commuting from the sample (e.g., see van Ommeren and van der Straaten 2008; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2018a, 2018b, 2021). However, omitting telecommuters may be problematic, as these workers could be included in the sample with zero commuting time. To partially address this issue, we re-do the main analyses in an expanded sample that includes telecommuters. The results and conclusions are robust to including telecommuters in the sample.

ATUS reports the racial category of respondents and includes the following categories: (1) “white”, (2) “black”, (3) “American Indian, Alaskan Native”, (4) “Asian”, and (5) “Hawaiian Pacific Islander”. We define dummy variables for being white or being black, as 93.62% of the sample is either white or black. On the other hand, the Hispanic origin of respondents refers to whether a respondent is of Hispanic/Spanish/Latino origin, and this is collected in a separate ATUS variable. Then, the means of these variables do not necessarily add up to 1.

Household annual income in the ATUS includes the following income ranges: (1) “less than $5,000”, (2) “$5,000 to $7,499”, (3) “$7,500 to $9,999”, (4) “$10,000 to $12,499”, (5) “$12,500 to $14,999”, (6) “$15,000 to $19,999”, (7) “$20,000 to $24,999”, (8) “$25,000 to $29,999”, (9) “$30,000 to $34,999”, (10) “$35,000 to $39,999”, (11) “$40,000 to $49,999”, (12) “$50,000 to $59,999”, (13) “$60,000 to $74,999”, (14) “$75,000 to $99,999”, (15) “$100,000 to $149,999”, (16) “$150,000 and over”. Occupation categories in the ATUS data include: (110) “Management”, (111) “Business, financial”, (120) “Computer and math science”, (121) “Architecture and engineering”, (122) “Life, physica, social science”, (123) “Community, social service”, (124) “Legal occ.”, (125) “Education, training, and library”, (126) “Arts, entertainment, sports, media”, (127) “Healthcare practitioner, technical”, (130) “Healthcare support”, (131) “Protective service”, (132) “Food preparation, serving”, (133) “Building, cleaning, maintenance”, (134) “Personal care service”, (140) “Sales and related”, (150) “Office and admin support”, 160) “Farming, fishing, forestry”, (170) “Construction, extraction”, 180) “Installation, maintenance, repair”, (190) “Production”, and (200) “Transport”. Occupations at a more disaggregated level are also available in the ATUS data.

MSA sizes report the population size of the metropolitan area in which a household is located. It takes the following values: (0) “Not identified or non-metropolitan”, (1) “100,000–249,999”, (2) “250,000–499,999”, (3) “500,000–999,999”, (4) “1,000,000–2,499,999”, (5) “2,500,000–4,999,999”, and (6) “5,000,000 + ”.

The ATUS diaries include information on the means of transportation of commuting episodes. We follow Gimenez-Nadal et al. (2021) and define dummy variables that identify private vehicle commuters, active commuters, and public transit commuters. The reference category represents commuters in other or unidentified means of transport.

Results when considering telecommuters shown in Table 12 are similar, although coefficients tend to be smaller given that telecommuters are associated with zero commuting time.

The fact that we cannot control for the distance between home and workplace, inducing omission bias, may explain such low R-squared.

Because we focus on episode details, and telecommuters do not report any commuting episode, this analysis is restricted to commuter workers.

This analysis resembles Gimenez-Nadal et al. (2021) study of asymmetries in the time of commutes to/from work.

Worker time allocations are correlated with commuting, which is a shock to worker time endowments (Shapiro & Stiglitz, 1984; Ross & Zenou, 2008; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2018b). Thus, it is likely that the time spent by workers doing activities throughout the day determines the time spent in intermediate activities while commuting. For example, individuals who do more leisure in their spare time may be less likely to do leisure while commuting, compared to counterparts who have less time available for leisure. However, the impact of worker time allocations on the time spent in intermediate activities while commuting is likely to be endogenous and lies beyond the scope of this analysis. We leave that analysis for future research.

The most remarkable difference between results in Table 6 and results in Table 12 (including telecommuters) regards coefficients associated with self-employment and parti-time workers. If telecommuters are included in the sample, being self-employed is not related to increased time in intermediate activities, while being a part-time worker relates to decreased time in intermediate activities while commuting from work. A potential explanation for such a difference is the fact that self-employed workers are generally more likely to report zero commuting, or to telecommute (e.g., taxi drivers), while part-time workers may be less prone to telecommute.

Similar statistics for the time spent in childcare, personal care, unpaid work, and using services, as intermediate activities while commuting, are shown in Table 9 in the Appendix.

References

Aguiar, M., & Hurst, E. (2007). Measuring trends in leisure: The allocation of time over five decades. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 969–1006.

Aguiar, M., & Hurst, E. (2009). A summary of trends in American time allocation: 1965–2005. Social Indicators Research, 93(1), 57–64.

Billor, N., Hadi, A. S., & Velleman, P. F. (2000). BACON: blocked adaptive computationally efficient outlier nominators. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 34(3), 279–298.

Bonke, J. (2005). Paid work and unpaid work: Diary information versus questionnaire information. Social Indicators Research, 70(3), 349–368.

Burd, C., Burrows, M., & McKenzie, B. (2021). “Travel Time to Work in the United States: 2019”, American Community Survey Reports, ACS–47, U.S. Washington, DC: Census Bureau.

Connolly, M. (2008). Here comes the rain again: Weather and the intertemporal substitution of leisure. Journal of Labor Economics, 26(1), 73–100.

Coria, J., & Zhang, X. B. (2015). State-dependent enforcement to foster the adoption of new technologies. Environmental and Resource Economics, 62(2), 359–381.

Cosaert, S., Theloudis, A., & Verheyden, B. (2023). Togetherness in the Household. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 15(1), 29–579.

Cropper, M. L., & Gordon, P. L. (1991). Wasteful commuting: A re-examination. Journal of Urban Economics, 29(1), 2–13.

Dargay, J. M., & Clark, S. (2012). The determinants of long distance travel in Great Britain. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 46(3), 576–587.

Fisher, K., Gershuny, J., Flood, S. M., Backman, D., & Hofferth, S. L. (2019). Multinational Time Use Study Extract System: Version 1.3 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS.

Foster, G., & Kalenkoski, C. M. (2013). Tobit or OLS? An empirical evaluation under different diary window lengths. Applied Economics, 45(20), 2994–3010.

Frazis, H., & Stewart, J. (2012). How to think about time-use data: what inferences can we make about long-and short-run time use from time diaries? Annals of Economics and Statatistics, 105(106), 231–245.

Fu, S., & Ross, S. L. (2013). Wage premia in employment clusters: How important is worker heterogeneity? Journal of Labor Economics, 31(2), 271–304.

Gershuny, J. (2012). Too many zeros: A method for estimating long-term time-use from short diaries. Annals of Economics and Statistics, 105/106, 247–270.

Giménez-Nadal, J. I., & Molina, J. A. (2016). Commuting time and household responsibilities: Evidence using propensity score matching. Journal of Regional Science, 56(2), 332–359.

Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., Molina, J. A., & Velilla, J. (2018a). The commuting behavior of workers in the United States: Differences between the employed and the self-employed. Journal of Transport Geography, 66(1), 19–29.

Gimenez‐Nadal, J. I., Molina, J. A., & Velilla, J. (2018b). Spatial distribution of US employment in an urban efficiency wage setting. Journal of Regional Science, 58(1), 141–158.

Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., Molina, J. A., & Velilla, J. (2020). Modelling commuting time in the US: bootstrapping techniques to avoid overfitting. Papers in Regional Science, 98(4), 1667–84.

Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., Molina, J. A., & Velilla, J. (2021). Two-way commuting: Asymmetries from time use surveys. Journal of Transport Geography, 95, 103146.

Giménez-Nadal, J. I., Molina, J. A., & Velilla, J. (2022). Trends in commuting time of European workers: A cross-country analysis. Transport Policy, 116, 327–342.

Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., & Sevilla-Sanz, A. (2011). The time-crunch paradox. Social indicators research, 102(2), 181–196.

Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., & Sevilla, A. (2012). Trends in time allocation: A cross-country analysis. European Economic Review, 56(6), 1338–1359.

Gobillon, L., Selod, H., & Zenou, Y. (2007). The mechanisms of spatial mismatch. Urban Studies, 44(12), 2401–27.

Guryan, J., Hurst, E., & Kearney, M. (2008). Parental education and parental time with children. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(3), 23–46.

Gutiérrez-i-Puigarnau, E., Mulalic, I., & Van Ommeren, J. N. (2016). Do rich households live farther away from their workplaces? Journal of Economics Geography, 16(1), 177–201.

Gutiérrez-i-Puigarnau, E., & van Ommeren, J. N. (2010). Labour supply and commuting. Journal of Urban Economics, 68(1), 82–89.

Hallberg, D. (2003). Synchronous leisure, jointness and household labor supply. Labour Economics, 10(2), 185–203.

Hamermesh, D. S. (2020). Life satisfaction, loneliness and togetherness, with an application to COVID-19 lock-downs. Review of Economics of the Household, 18(4), 983–1000.

Hamermesh, D. S., Myers, C. K., & Pocock, M. L. (2008). Cues for timing and coordination: latitude, letterman, and longitude. Journal of Labor Economics, 26(2), 223–246.

Hamilton, B. W. (1989). Wasteful commuting again. Journal of Political Economy, 97(6), 149–1504.

Hofferth, S. L., Flood, S. M., Sobek, M., & Backman, D. (2020). American Time Use Survey Data Extract Builder: Version 2.8 [dataset]. College Park, MD: University of Maryland and Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS.

Horner, M. W. (2004). Spatial dimensions of urban commuting: a review of major issues and their implications for future geographic research. The Professional Geographer, 56(2), 160–173.

Jenkins, S. P., & Osberg, L. (2005). Nobody to play with? The implications of leisure coordination. In D. Hamermesh & G. Pfann (Eds.), The Economics of Time Use, Contributions to Economic Analysis No. 271 (pp. 113–145). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Kahn, M. E. (2000). The environmental impact of suburbanization. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 19(4), 569–586.

Kimbrough, G. (2019). Measuring commuting in the American Time Use Survey. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement, 44(1), 1–17.

Kirby, D. K., & LeSage, J. P. (2009). Changes in commuting to work times over the 1990 to 2000 period. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 39(4), 460–471.

Le Barbanchon, T., Rathelot, R., & Roulet, A. (2021). Gender differences in job search: Trading off commute against wage. The. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(1), 381–426.

Manning, A. (2003). Monopsony in motion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

McKenzie, B., & Rapino, M. (2009). Commuting in the United States: 2009. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau.

McQuaid, R. W., & Chen, T. (2012). Commuting times: The role of gender, children and part-time work. Research in Transportation Economics, 34(1), 66–73.

Mulalic, I., van Ommeren, J. N., & Pilegaard, N. (2014). Wages and commuting: Quasinatural experiments’ evidence from firms that relocate. Economic Journal, 124(579), 1086–1105.

Roberts, J., Hodgson, R., & Dolan, P. (2011). It’s driving her mad: Gender differences in the effects of commuting on psychological health. Journal of Health Economics, 30(5), 1064–1076.

Rodríguez, D. A. (2004). Spatial choices and excess commuting: a case study of bank tellers in Bogotá, Colombia. Journal of Transport Geography, 12(1), 49–61.

Ross, S. L., & Zenou, Y. (2008). Are shirking and leisure substitutable? An empirical test of efficiency wages based on urban economic theory. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 38(5), 498–517.

Ruppert, P., Stancanelli, E., & Wasmer, E. (2016). Commuting, wages and bargaining power. Annals of Economics and Statistics, 95/96, 1.

Sandow, E. (2008). Commuting behaviour in sparsely populated areas: evidence from northern Sweden. Journal of Transport Geography, 16(1), 14–27.

Sandow, E., & Westin, K. (2010). Preferences for commuting in sparsely populated areas: The case of Sweden. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 2(3/4), 87–107.

Shapiro, C., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1984). Equilibrium unemployment as a worker discipline device. American Economic Review, 74(3), 185–214.

Small, K. A., & Song, S. (1992). Wasteful commuting: A resolution. Journal of Political Economy, 100(4), 888–898.

Van Acker, V., & Witlox, F. (2011). Commuting trips within tours: How is commuting related to land use? Transportation, 38(3), 465–486.

Van Ommeren, J. N., & Van der Straaten, J. W. (2008). The effect of search imperfections on commuting behavior: Evidence from employed and self-employed workers. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 38(2), 127–147.

White, M. J. (1986). Sex differences in urban commuting patterns. American Economic Review, 76(2), 368–372.

White, M. J. (1999). Urban areas with decentralized employment: Theory and empirical work. Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, 3, 1375–412.

Yee-Kan, M. (2008). Measuring housework participation: The gap between “stylised” questionnaire estimates and diary-based estimates. Social Indicators Research, 86(3), 381–400.

Zax, J. S. (1991). Compensation for commutes in labor and housing markets. Journal of Urban Economics, 30(2), 192–207.

Funding

This work was supported by the Government of Aragón [Project S32_20R]; and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation [Project PID2019–108348RA-I00]. J. Velilla acknowledges funding from the Cátedra Emprender [Project C006/2021_2]. Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Additional results

Appendix B: Results including telecommuters

The evolution of commuting time. Note: The sample (ATUS 2003–2019) is restricted to employees who worked the diary day. Telecommuters are included. Commuting is measured in minutes per day. Commuting ATUS includes commuting episodes only. Commuting and intermediate trips includes all the intermediate trip activities. Bulk commuting includes trip and non-trip intermediate activities

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giménez-Nadal, J.I., Molina, J.A. & Velilla, J. Intermediate activities while commuting. Rev Econ Household (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-023-09684-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-023-09684-4