Abstract

This paper contributes to the research on heterogeneity in labor force participation decisions between women. This is done by discussing the role of the personality trait locus of control (LOC), a measure of an individual’s belief about the causal relationship between behavior and life outcomes, for differences in participation probabilities. The association between LOC and participation decisions is tested using German survey data, finding that internal women are on average 13 percent more likely to participate in the labor force. These findings are also found to translate into higher employment probabilities at the extensive and intensive margin as well as in a lifetime perspective. Additional analyses identify a strong heterogeneity of the relationship with respect to underlying monetary constraints and social working norms. In line with the existing literature, an important role of LOC for independence preferences as well as subjective beliefs about returns to investments are proposed as theoretical explanations for the findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Research on female labor force participation has a long tradition. Triggered by the growing labor supply of women in the second half of the last century, a large strand of theoretical and empirical research on this issue has developed over the past decades. Especially the gender differences in participation and its potential explanations have been the center of attention in the economic literature (see e.g., Angrist, 2002, Blau & Kahn, 2007, 2017, Goldin, 1990, Goldin & Katz, 2002, Juhn & Murphy, 1997, Mincer, 1962). The most recent research has put much focus on non-monetary incentives and disincentives such as in specific social norms in order to explain gender gaps (see e.g., Bertrand et al., 2015, Charles et al., 2018, Fortin, 2015, Gay et al., 2017, Goldin, 2006, Knabe et al., 2016).

Based on this literature, we already know a lot about why women keep on having elower participation rates and why these variables started converging in recent decades. However, between-women heterogeneity in participation probabilities can only be explained within this framework to a limited extend. Traditional economic models largely attribute these unexplained differences in decision outcomes to idiosyncratic shocks or unobserved constraints and opportunities. As opposed to this, modern behavioral economic and applied microeconomic approaches started investigating these differences with respect to unobserved, inherent beliefs and preferences. A growing literature is thus interested in investigating the psychological black box behind female labor supply. Especially the most recent literature investigates the role of inherent personal attributes for female decision making on the labor market (see e.g Wichert & Pohlmeier, 2010).

This paper contributes to the literature by investigating the role of a specific personality trait, an individual’s perception of control, also called locus of control (LOC), for women’s labor supply decisions. LOC can be characterized as a "generalized attitude, belief, or expectancy regarding the nature of the causal relationship between one’s own behavior and its consequences”(Rotter, 1966) and describes whether individuals believe in the effects of their own efforts and abilities on their life outcomes. While individuals with an internal LOC (internals) believe that their own efforts and abilities will be rewarded in their future, individuals with an external LOC (externals) attribute life outcomes mainly to luck, chance, fate or other people. LOC has already been shown to have an important effect on economic behavior and decision making on the labor market in such areas as educational attainment (Coleman & DeLeire, 2003, Mendolia & Walker, 2015), job search effort (Caliendo et al., 2015, McGee & McGee, 2016), occupational attainment (Cobb-Clark and Tan, 2011, Heywood et al., 2017), entrepreneurial activity (Caliendo et al., 2014, Hansemark, 2003) and labor market mobility (Caliendo et al., 2019) and, as an outcome of them, wages (Osborne Groves, 2005, Schnitzlein & Stephani, 2016, Semykina & Linz, 2007).Footnote 1 Nevertheless, literature that directly relates female labor force participation to LOC is scarce. Most prominently, Heckman et al. (2006) find a significant positive effect of a combined measure of LOC and self-esteem on the individual probability of being employed at age 30 for the sample of young individuals from the NLSY79. They show that this relationship is much more pronounced for females. Using Australian data from the HILDA, Xue et al. (2020) find that these results on higher employment probabilities for internal individuals can be replicated using twin fixed effects in a sample of non-identical twins while they vanish if identical twins are used. They argue that this indicates a high importance of genetic factors in the formation of LOC. Berger and Haywood (2016) analyze the effect of LOC on mother’s return to employment after parental leave. Using German survey data, they find that women with an internal LOC return to employment more quickly. Based on a heterogeneity analysis with respect to the underlying flexibility in the women’s occupations, they conclude that the effect is mainly driven by different subjective expectations about future career costs of maternity leave. That study is most closely related to the paper at hand. Nevertheless, Berger and Haywood (2016) concentrate on a very specific group of women in a rather exceptional stage of life and the study thus lacks external validity for the decision making for other women. The study at hand is intended to draw a much more general picture and shed light on the important interplay between constraints and preferences in female decision making on the labor market. In addition, this study especially contributes to the discussion of the individual decision making processes underlying the participation of women on the labor market. While the existing economic literature on LOC was mainly concentrated on the role of LOC for subjective expectations about future payoffs, this study also considers the role of personality profiles for preferences in line with the psychological literature. Additionally, the explicit consideration of the interplay between personality and underlying preferences with monetary and non-monetary constraints is new to the literature on female labor force participation as well as the literature on behavioral effects of personality traits.

The theoretical considerations mainly discuss two potential mechanisms of the association of LOC and labor force participation, which are (1) difference in the direct marginal utility from participating as well as (2) differences in the subjective beliefs about returns to investment. Firstly, based on the psychological literature on the connection between LOC and independence considerations, the direct non-monetary gain from participation is expected to be higher for internal women. Internals put greater weight on the status of being active l. They not only derive utility from the consumption level as an outcome of participation, but also from the fact that they themselves had control over generating it. Secondly, in line with earlier literature (Caliendo et al., 2015), LOC can be assumed to have an effect on beliefs about positive future returns to individual efforts, such as parental investments, job search and the investments into future career advancements.

Therefore, in the empirical part of the paper, the conditional association between LOC and current labor force participation of a woman is estimated in a reduced form approach. The estimations are conducted using the extensive information available from the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, 2020), a large representative longitudinal household panel from Germany. Using this data, the average marginal effects of a woman’s LOC on her probability of participating in the labor force is estimated using a binary logit estimation conditional on standard socio-economic determinants of participation. In this context, labor force participation is defined as a general availability for market production in line with the definition of the International Labor Organization (2018) and thus concentrates on the behavioral implications of LOC on labor supply decisions. The analysis finds a significant positive relationship between having an internal LOC and being available to the labor market. Internal women are on average 13 percent less likely to stay at home. Nevertheless, the relationship is found to be non-linear with especially very external women having significantly lower participation rates. Additional analysis reveals that these effects also translate into significantly higher actual labor force activity at the extensive and intensive margin, also in a lifetime perspective. Furthermore, a subgroup analysis reveals that while a strong relationship can be observed for cohabiting women and mothers, the effect for childless women is lower or even zero, depending on family status. This indicates a crucial heterogeneity with respect to underlying monetary incentives to work. In addition, a second heterogeneity analysis shows that the estimated effects are also sensitive to the underlying social norms of working as measured by regional as well as cohort differences.

The outline of the paper is as follows. Section 2 gives a brief overview the theoretical considerations behind the empirical analysis. Section 3 describes the data as well as the empirical strategy and Section 4 presents the main estimation results. Section 5 gives an overview over various heterogeneity analyses. The paper concludes in Section 6.

2 Theoretical considerations

Based on the underlying definition of LOC, multiple hypotheses can be formed about the relationship between LOC and female labor force participation which will guide the empirical analysis. All further considerations will assume a static decision situation which abstracts from the formation process of LOC. This is based on the assumption of relative stability of LOC during adulthood, which will be discussed in further detail in Section 3. Additionally, as the focus of this paper is to analyze the behavioral aspects of labor supply, it concentrates on labor force participation as opposed to actual employment. This reduces the risk of biased results due to omitted returns in employment probability in the empirical section. In line with the ILO definition of “labor force”, a woman is assumed to participate on the labor market if she is either already employed or self-employed or if she is unemployed and intends to participate by indicating that she is searching for a job (see International Labor Organization, 2018). Thus, labor force participation also equals one if the woman does not work but is available to the market through job searching. In this simplification, given a certain expected market wage, no assumptions on labor market conditions and frictions are necessary. The link between a woman’s labor force participation decision and her individual characteristics only depends on her individual preferences and expectations and not on demand-side responses to her characteristics, i.e., a higher or lower employment probability based on e.g., her LOC. In line with this simplification, labor force participation is thus reduced to a binary decision, i.e., for or against participation, at the extensive margin and abstracts from the continuous decision at the intensive margin, i.e., working hours or employment years over the life cycle.

Within this framework, the decision making of the woman can be formalized using a basic neoclassical model of labor-leisure choice in which the woman maximizes her utility function

given the limitations imposed by her budget constraint

with C being the woman’s consumption level, L being leisure or more general all time not spend on labor force participation. Thus leisure equals the total time allocated to the woman T minus the number of hours she decides to supply given the return she expects from each unit of labor supply \(\tilde{w}\). \(\tilde{w}\) thus refers to the expected net hourly wages (which depends on the gross wage itself (Mincer, 1962) the tax regime (Eissa & Liebman, 1996, Fuenmayor et al. 2016, James, 1992) but also child care costs (Morrissey, 2016) as well as the probability of receiving this wage (i.e., the job-offer arrival rate) (Caliendo et al., 2015). V corresponds to her non-labor income, which includes e.g., partners income (Devereux, 2004, Lundberg, 1988) or social transfers.

The purpose of this formal depiction is to create a theoretical framework for the empirical findings discussed in the later sections and not to build the most realistic and detail theoretical model of the decision making of women between paid work, unpaid work and leisure. This is why the framework explicitly abstracts from a formal differentiation of unpaid work and leisure time. The empirical focus of the paper is on the decision whether the woman decides to work or not to work, independent from how the time not at paid work is spent. Thus, the time not spend for paid work is condensed under the label “leisure” although differences between leisure and unpaid work will be considered in the formation of hypothesis on the role of LOC.

Based on this framework, three major mechanisms for an association between LOC and female labor force participation are proposed: 1) differences in the marginal utility from participation driven by latent preferences, 2) differences in the subjective expected returns to efforts such as e.g., job search or parental and workplace investments and 3) direct monetary returns to differences in LOC.

Preferences The first potential channel suggests that LOC affects a woman’s preferences for the different components of her utility function and thus the marginal utility she derives from participation. In line with Almlund et al. (2011), we can assume that a woman’s marginal gains from leisure and consumption depend on a vector of individual attributes and preferences which are i.e., shaped by personality traits such as e.g., locus of control loci.

Based on the basic idea of the model, we can assume that non-monetary benefits from working, i.e., the “joy of working” is captured by the woman’s preference for leisure. This component incorporate, besides others, known concepts like identity and purpose (Akerlof & Kranton, 2000, Jahoda, 1981, Knabe et al., 2016) but also financial and economic independence.

Similar to the argumentation in Cobb-Clark et al. (2014) about the effect of LOC on healthy behavior, internal women (i.e., women with a high LOC) are likely to have a stronger preference for being active on the labor market than external women because they prefer to directly affect their life outcomes and thus be independent of external forces. Thus, they derive more direct utility from participation than externals do, i.e., less utility from leisure time:

Holding everything else constant, an internal woman is on average more likely to participate than an external woman as her marginal rate of substitution (\(\frac{\partial {U}_{i}/\partial {L}_{i}}{\partial {U}_{i}/\partial {C}_{i}}\)) is lower, i.e., she is willing to give up more leisure hours in exchange for an additional unit of consumption. Thus, consumption which is generated from self-earned income is valued higher than consumption generated from external income such as partner’s earnings or social transfers. Based on these theoretical considerations, internal women are ex-ante expected to be more likely to participate.

These considerations are in line with findings from earlier economic and psychological literature. We, for example, already know from the existing literature that income autonomy is an important driver of labor division of paid and unpaid work in couples (Görges, 2014). The role of independence and autonomy considerations for LOC has already been discussed especially in the context of early childhood skill formation in the psychological literature (see e.g., Hill, 2011, Wichern & Nowicki, 1976).

As opposed to this, in the presence of children in the household, internal women might consider the effect of own actions on their children more carefully than external women. This is in line with the findings by Lekfuangfu et al. (2018) on the strong effect of maternal LOC on attitudes towards parental style as well as actual parental time investments. Thus internal mothers might have stronger preferences for home production. If we assume that home production in this very simple model is captured by leisure Li (i.e., the opposite of participation), internal women might derive higher utility from every unit of Li: \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{U}_{i}}{\partial {L}_{i}\partial lo{c}_{i}} \,>\, 0\) and might thus on average be less likely to participate.

Subjective Expectations The second channel proposes that LOC directly affects a woman’s subjective expectations about the returns to own efforts and investments. The expected monetary returns to participation are higher for internal individuals as they believe in the direct causality between their own efforts and life outcomes. Internal women have higher subjective job-offer arrival rates and higher subjective future income paths (Berger & Haywood, 2016, Caliendo et al., 2015). Hence, they expect higher (current and future) returns to participation and have a steeper budget curve: \(\frac{\partial {\tilde{w}}_{i}}{\partial lo{c}_{i}} \,>\, 0\).

Internal woman thus expect higher utility from availability for market production as their budget constraints allows for higher returns to participation in expected consumption levels. They are, on average, more likely to participate.

Monetary returns to LOC Besides these two main mechanisms, the raw difference between internal and external women could also be driven by differences in the objective monetary returns to LOC and thus, indirectly, via different constraints. One potential explanation for this may be positive demand-side responses to an internal LOC, i.e., higher realized wage rates (Heineck & Anger, 2010) which are correctly anticipated by women and thus incorporated into the decision-making independent from the subjective beliefs. Additionally, internal women have been found to select occupations that are less open for flexible employment paths (Cobb-Clark & Tan, 2011). These occupations are likely to be associated with higher future career costs of non-participation and thus higher disincentives for home production. Additionally, LOC might also be correlated with the partners’ earnings, captured by Vi and thus family income driven by assortative mating or mating probabilities in general (see e.g., Lundberg, 2012).

Nevertheless, as opposed to the first two hypothesized channels, this heterogeneity can be captured by a number of control variables and is discussed in Section 4.2 in more detail.

3 Data and empirical identification

Based on these theoretical considerations, the goal of this paper is to empirically analyze the role of LOC in explaining women’s current labor force participation. This is done by using data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, 2020). The SOEP is an annual representative household panel that follows a general-purpose approach. It has been studying about 22,000 individuals living in 12,000 households in Germany since 1984. Personal questionnaires are completed by all individuals aged 18 or older. For more information on the SOEP see Goebel et al. (2019). The SOEP contains a measurement of LOC over multiple waves, rich information on current labor-market outcomes and family status as well as the opportunity to connect women to their partners’ characteristics if they are surveyed in the same household.

Sample Restriction The sample restriction process is intended to create a relatively homogeneous sample of women who could potentially participate in the workforce. Thus, the sample only consists of women in the traditional working age, which is defined as 25 to 65 years, as well as only women who are not in school, academic or vocational education, not already in (early) retirement or in military service. Additionally, only women who live in single-adult or in couple households with or without children are kept. All women in multi-generation households or other unknown household combinations are dropped in order to enable a more straightforward argumentation about intra-household decision making.Footnote 2 Finally, only women for whom it is possible to observe all the relevant socio-economic control variables are kept. This leaves 70,662 observations for 11,013 women over the period 2000 to 2018 in which women are observed for, on average, 10.35 years. Column (1) in Table A.1 in the Appendix gives an overview of the descriptive statistics of the sample.

3.1 Locus of Control

LOC is surveyed within the SOEP in the years 1999, 2005, 2010 and 2015. Respondents are asked how closely a series of 10 statements characterizes their views about the extent to which they influence what happens in life. A four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘applies fully’) to 4 (‘does not apply’) was used in 1999, while in 2005, 2010 and 2015, responses were measured on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘disagree completely’) to 7 (‘agree completely’). A list of the items can be found in Table A.2 in the Appendix.

In order to harmonize the scales, the responses from 1999 are reversed and “stretched”.Footnote 3 Afterwards, an exploratory factor analysis is conducted jointly for all years in order to investigate the way these items load onto latent factors. The factor analysis clearly indicates one underlying factor with an eigenvalue of 1.78 (with the eigenvalue of a second factor being 0.55). The rotated factor loadings indicate that items 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 and 10 have a positive loading and item 1 has a negative loading on this factor.Footnote 4 Items 4, 6 and 9 have relatively low factor loadings and are excluded from the factor prediction.Footnote 5 Excluding these three items improves the internal consistency and scale reliability of the resulting factor, as Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach, 1951) increases from 0.63 to 0.69, which is in line with the findings from Specht et al. (2013). Nevertheless, the estimation results are robust against the inclusion of item 4,6 and 9. Results of the sensitivity check can be found in Section 4.4. In line with the previous literature (see e.g., Piatek & Pinger, 2016), a two-step procedure is used in order to create a continuous and uni-dimensional LOC factor. First, the scores for items 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 and 10 are reversed such that all seven items are increasing in internality. Second, confirmatory factor analysis is used to extract a single factor. This has the advantage that it avoids simply weighting each item equally, as averaging would do, and instead allows the data to determine how each item is weighted in the overall index. Simple averaging of items would risk measurement error and attenuation bias (Piatek & Pinger, 2016).Footnote 6

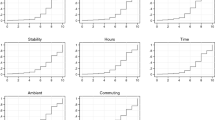

The resulting factor is increasing in internal LOC and its distribution is shown in Fig. 1. In order to fill the observation gaps, LOC is imputed forwards lagged by at least one year, i.e., the LOC observed in 1999 is imputed into the years 2000 to 2005 and so forth. On the basis of the generated and imputed continuous LOC factor variable, a categorical variable is created that splits the continuous LOC in three terciles, in order to identify non-linear relationships.

SOEP, waves 2000–2018, version 36, https://doi.org/10.5684/soep.v35, own illustration

3.2 Labor force participation

Labor force participation (LF) is measured as a binary indicator that indicates a woman’s availability to the labor market. The decision at the extensive margin still is the most prominently discussed decision situation in female labor force participation especially with respect to intrinsic factors such as personality traits. Decisions about participation at the intensive margin are often much more strongly determined from the demand side with, for example, working hours being commonly restricted to specific full-time and part-time options. An additional analysis (in Section 4.3) nevertheless will also take a closer look at labor force activity at the intensive margin as well as lifetime participation in order to complement the results of the main analysis.

In line with the ILO definition of labor force participation, a woman is counted as being in the labor force if she is either employed or self-employed or if she is registered unemployed or non-working (not registered unemployed) but intends to work and is searching for a job (see International Labor Organization, 2018). Registered unemployed and non-working women are re-coded on the basis of the information available on intention to work, active search and ability to start working from the personal questionnaire.Footnote 7

Table 1 gives an overview of the current labor force status of women in our sample. In the full sample of all women (column 1), 71.90% are employed, 5.96% are self-employed, 6.57% are unemployed and in total 15.58% indicate that they are not working or are on maternity leave. If, in addition to these raw shares, the information on active job search, intention to work and availability to start working are also considered, a labor force participation rate of 82.08% results, as only 3.53% are unemployed and indicate that they are actively searching plus another 0.45% of individuals are coded as not working but indicate that they are searching for a job. When compared to official statistics on labor force participation in Germany, available from the International Labor Organization (2018), this share seems reasonable. While the total estimated labor force participation of women from the EU Labor Force Survey, which was 56% in 2018, refers to all women in the age of 15 or above, the participation share of women between 25 and 64 is with 83% very similar to the shares in the SOEP-sample.

Table 1 also gives descriptive evidence for the relationship between LOC and labor force status and participation of the women in the sample. The shares of all labor force statuses, as well as the dependent variable LFit, are given separately for all three terciles of LOC. It can be seen that due to a higher share of employed and self-employed women and a lower share of non-working women for the medium and highest tercile, the overall share of LF is higher for women with a medium and a high LOC than for those with a low LOC. This is also supported by the kernel densities illustrated in Fig. 1, which clearly indicates an interesting non-linearity in the raw association between LOC and labor force participation.

Nevertheless, this descriptive relationship is very likely to be driven by a long list of socio-demographic characteristics that are associated with a higher participation probability and a higher LOC, such as education, age and family status (e.g., number and age of children) and other strongly correlated personality traits. See Table A.1 for summary statistics separately for all three terciles of LOC.

3.3 Estimation strategy

For the main empirical analysis, a reduced-form approach is employed to estimate the association between a woman’s propensity to be available to the labor force and her last LOC:

where LFit is the indicator for labor force participation of woman i at time t and locit−n is the LOC of woman i in the last LOC interview prior to t, i.e., n interviews prior to t with n = {1, …, 6}. In order to identify potential non-linearities in the relationship, the analysis is repeated with a categorical variable that indicates in which tercile of the LOC distribution a woman is classified.

As the most basic set of control variables, we control for a comprehensive list of time and regional variables (Iit) such as the year and month of the interview. Additionally, Iit includes federal state fixed effects as well as an indicator for the rurality of the region to control for regional variation in LOC and labor force participation.Footnote 8

In a next step, we add Xit, a vector which contains an extensive list of socio-demographic information (age, nationality, mental health and physical health scalesFootnote 9 as well as highest school and vocational degree).

Additionally, Fit complements the list of control variables with a number of family characteristics (partner status, number of children, indicators for children in certain age ranges and pregnancyFootnote 10 as well as unearned household incomeFootnote 11).

Next, Pi completes the full specification with control variables with an extensive set of inherent preferences and personality traits measures. This set includes risk preferences (willingness to take risk), time preferences (patience and impulsiveness) and the Big Five personality traits (openness, conscientiousness, agreeableness, extraversion, neuroticism). All personality and preferences measures are standardized and included as a time-invariant average over all available observations due to observation gaps. See Table A.1 for the full list of controls.

Equation (5) is estimated using a binary logit model. Standard errors are clustered on the personal level which considers the panel structure of the data and takes care of serial correlation of the error term ϵit across time for a given individual i. The results presented in Section 4.1 are the average marginal effects.

Identification Issues—Reverse Causality and Omitted Variable Bias The study at hand suffers from two major identification issues which are (1) the risk of reverse causality due to the instability of LOC itself or its measurement as well as (2) the endogeneity of LOC due to omitted variable bias. The first issue has largely been discussed in the related literature and is mostly dismissed with references to studies which find indication for relative stability of underlying LOC in adulthood with respect to lifetime events such as for example Cobb-Clark and Schurer (2013). In order to further minimize concerns about potential reverse causality most studies ensure that LOC is always included as a pre-market rather than a contemporaneous or post-market measure, i.e., always obtained prior to t. This approach is also taken in the empirical study at hand as LOC is imputed forward lagged by at least one period. Nevertheless, based on the findings in Preuss and Hennecke (2018), this procedure does not prevent the risk of selection and attenuation bias due to a temporary measurement error in LOC for example during periods of unemployment. If individuals tend to report their LOC differently in periods of unemployment, this might distort the findings in this study as unemployment is a crucial part of the outcome variable of interest. In line with this, additional sensitivity checks are conducted, in which LOC is imputed from the closest employment spell of the women as well as an average over all available observation periods and the first available LOC observation, which reduces the risk of the instability in measurement. The findings are discussed in Section 4.4.

Secondly, a major drawback of the study at hand is the inevitability of endogeneity in LOC even if it is assumed to be stable during adulthood. Although the model already controls for an extensive list of exogenous as well as potentially endogenous control variables, the observed relationships are still likely to be affected by omitted unobserved heterogeneity such as e.g., parental upbringing (see for example Carton & Nowicki, 1994) and thus are only conditional associations due to the strong link of LOC with countless unobservable aspects of individual socialization, behavior and life outcomes. Based on the findings in Preuss and Hennecke (2018), it can be assumed that much of the observable within-individual variation in LOC is likely to arise from temporary measurement inaccuracy and noise. It is thus not possible to use an individual fixed effects framework in order to test whether within-person changes in LOC are predictive of future labor participation. Also the use of twin or sibling fixed effects models such as in Xue et al. (2020) is not feasible in the study at hand due to the very low number of observed female siblings in the estimation sample. Thus, the study at hand concentrates on the clean estimation of conditional associations with a rich set of control variables and the sensitivity of the results with respect to omitted variables following Oster (2019) will be further analyzed in Section 4.4.

4 Results

4.1 Main results

Table 2 presents an overview of the estimated average marginal effects of LOC while gradually including more and more sets of control variables for the full estimation samples of all women. This is done for the continuous LOC variable in columns (1) to (5) while estimates for the categorical LOC variable is presented for the full specification in column (6).

In line with the descriptive evidence in the previous subsection, the results of the raw difference, as well as of the specification which only controls for time and regional characteristics, indicate that, on average, the estimated marginal effect of LOC is significantly positive, indicating an increasing probability of participation with increasing values of LOC (column 1 and 2). Including additional control variables indicates that the raw gap was biased upwards by omitted variable bias through socio-demographic background as well as other personality traits while family characteristics seem to have biased the estimates downwards. Also, in the full specification (columns 5 and 6), the average marginal effect is still statistically and economically significant. Increasing the LOC by approximately one standard deviation, increases the probability of participation by 1.2 percentage points (column 5). When comparing this effect to the mean non-participation rate in the full sample of 18 percent (see Table 1), this amounts to a 6.6 percent decrease in the probability of staying at home.

Having a medium (or a high) LOC increases the probability of being in the labor force by, on average, 2.4 (2.2) percentage points compared to having a low LOC (i.e., a roughly 13 percent decrease in the probability of staying at home).

When comparing the marginal effects of a medium and a high LOC, a non-linearity in the effect of LOC on the participation probability becomes apparent. While a medium LOC is associated with an increased probability of participation, this effect flattens out. Women with a very high LOC are not significantly more likely to participate than women with a medium LOC. In line with the one-dimensionality of the LOC scale, the findings indicate that the effect is mainly driven by a negative impact of being strongly external, rather than a positive impact of being strongly internal.

When compared to the effect of other important predictors of female labor force participation (see Table S.1 in the Supplementary Material), these effects are also reasonably big in economic terms. The effect of a one standard deviation increase in LOC is comparable to the effect of a similar increase in risk attitude and larger than the effect of e.g., agreeableness or neuroticism but lower than the effect of e.g., conscientiousness. Having a medium or high LOC (as compared to a low) has a stronger effect on the participation probability than for example one child less or being single (as compared to being married) and a similar effect to, for example, having an apprenticeship (as opposed to no vocational degree).

4.2 Channels and endogenous controls

In order to rule out a number of alternative mechanisms behind a conditional association between LOC and LFP while still considering potential “bad control” issues in line with Angrist and Pischke (2008), a number of potentially endogenous control variables are added to the model in the next step. The results can be found in Table A.3 in the Appendix as well as Table S.2 in the Supplementary Material.

First, a set of latent belief and ideology control variables is added to the specification. These variables, which include religious as well as political party affiliation and life satisfaction, are likely to be highly correlated with female labor force participation and LOC but the direction of the effect between LOC and these variables is less clear, which is why they are treated as endogenous variables as opposed to exogenous control variables. As these variables are not observed for all women in our original estimation sample, column (2) gives the estimation results for the reduced sample without these variables, while the variables are added to the specification in column (3). In line with expectation, including the variables reduces the effects by approximately 17–27% but the effect remains positive and statistically significant.

Secondly, as has been discussed in the theoretical considerations, differences in participation probabilities between internal and external women might be driven by omitted differences in the objective budget constraints. Thus, controlling for them is necessary to identify the direct behavioral effect of LOC on participation decisions instead of the indirect effects through differences in opportunities and constraints such as occupational selection and wage differences. Due to a high likelihood of path and state dependencies in employment biographies, controlling for these potentially endogenous variables is, however, not straightforward. Simply including the information on the current or last job would leave us with a large multicollinearity problem caused by the characteristics themselves, but especially by their availability in general. The information on employment characteristics (occupation and wage) has to be imputed from the last employment or self-employment spell if a woman is not (self-)employed at the moment. Nevertheless, it is not possible to observe any information on employment for a lot of women if they were either never employed or at least never employed during their time in the SOEP. This is, by definition, more often the case in the group of women who do not participate in the labor force at the moment. Driven by this proposed role of state dependence, the indicator for non-availability of the information would thus be a “bad control”, in line with the arguments by Angrist and Pischke (2008), as it is highly multi-collinear with the labor force participation indicator. Not only are external women more likely to be observed outside the labor force at the moment, but they are also more likely never to be observed in the labor force, and the indicator could just as well be a dependent variable in the estimation model. To disentangle the endogeneity problem from the true effects of controlling for occupational characteristics and wages, column (4) of Table A.3 starts by reducing the observation sample to the women who are observed in occupation during their time in the SOEP at least once (“ever employed”). In line with expectations, the estimated effects for the LOC drop if the sample is reduced, indicating an endogeneity problem due to state dependencies in the observability of information. Hence, the estimated effects from this reduced sample are taken as the new baseline in the following, in order to eradicate parts of the bad control problem. In columns 5 and 6 of Table A.3 potentially omitted information on the industry and occupation type of women in their current or last job, as well as net labor income of the last observed working spell, are added as controls to the model. Although the effect size does go down, especially when wage is controlled for, the effects remain significantly positive. Hence, an effect of LOC on participation probabilities via occupational selection and differences in the expected future costs of non-participation can largely be rejected while we do observe a demand-side response to LOC via higher expected wages which leads to higher participation probabilities.

Lastly, information on a woman’s partner has to be controlled for in order to rule out assortative mating as a cause for the observed relationship between LOC and labor force participation. Fortunately, the SOEP makes it possible to merge cohabiting women with their partners. Thus, column 8 present the results of the estimation in which the partner’s current net labor income is included as additional control variables for cohabiting women. The results do not change if partner’s net income and LOC are included as control variables, indicating that the results of the main estimation are not driven by assortative mating.

4.3 Labor force activity, working hours and lifetime participation

The behavioral implications of LOC on labor force availability have been the center of attention in the theoretical considerations as well as the main part of the empirical analysis. Nevertheless, it is interesting to investigate whether those static behavioral effects actually translate into higher employment probabilities, higher participation on the intensive margin as well as higher average lifetime participation, as these are the variable with the desired positive macro- and microeconomic consequences in the long run. If a higher probability of being available to the market for internal women does not translate into higher employment probabilities, the positive economic implications of LOC are limited by other unobserved factors such as market conditions and frictions.

In order to assess the generalizability of the results with respect to the choices made about the participation indicator as described in Section 3.2, three major components of the dependent variable are investigated: (1) the concentration on labor force availability instead of labor force activity, (2) the restriction to the extensive margin as well as (3) the focus on a one-period discrete choice rather than a intertemporal lifetime perspective on labor force participation. The results of these additional estimations can be found in Table 3.

Labor Force Activity and Working Hours As a first step, the dependent variable is adjusted such that it only captures labor force activity (“working”) instead of availability. Thus, the indicator is one if a woman is actually employed or self-employed and zero if she is unemployed or not-working, independent of her intention to work. This alternative definition was neglected in the main part of the empirical analysis as it captures unobserved returns to LOC with respect to employment probabilities and therefore does not concentrate on the behavioral aspects of labor force participation.

Column 1 of Table 3 give the results of this new indicator while still concentrating on the extensive margin. The results indicate that the behavioral changes are fully translated into higher employment probabilities. The effects are considerably stronger than in the main estimations. This is likely due to unobserved returns to LOC in employment probabilities as observed in the negative correlation between LOC and unemployment as seen in Table 1. Having a medium (high) LOC thus on average increases the probability of working by 3.7 (3.9) percentage points.

In addition to this, columns 2 and 3 give the estimated marginal effects of LOC on participation indicators at the intensive margin. For the sub-sample of all women who are employed (LF = 1 in column 1), the outcome variable in column 2 indicates the actual working hours (contracted hours plus overtime) of a woman whereas the outcome variable in column 3 indicates whether a woman is full-time employed (FT), defined by at least 35 contracted working hours per week. As the goal of the main estimation model was to capture behavioral changes in participation decisions instead of actual labor force activity, which is strongly influences by demand side restrictions such as fixed full- or part-time options for working hours, this continuous measure of participation was neglected in all previous analysis.

While a medium LOC positively affects labor force availability as well as participation at the extensive margin, no effects can be identified at the intensive margin. As opposed to this, having a high LOC does on average increase the amount worked by 0.43 hours and the probability of being full-time employed by 1.6 percentage points.

Lifetime Participation Additionally, the lifetime perspective should be considered in order to understand whether this static relationship actually translates into differences for the whole working life due to the potentially important role of path and state dependencies in women’s employment biographies. Thus, in the additional results presented in columns 4 to 7 of Table 3, the accumulated years in the labor force as well as in employment between the age of 25 and 65 are the outcome variables of interest. Using the detailed biographical information available for every SOEP participant, the aggregated time in the labor force is calculated by adding the years a woman spent in employment or registered unemployment during those 40 years.Footnote 12 As no biographical information is available on the job-search behavior, the analysis relies on the reported labor force status in order to identify LF. As job-search is likely to be an important determinant of true willingness to participate, it has to be taken into account that this is, therefore, only a rough measure of participation. The cross-sectional estimation sample consists of the first available observation for women in the age of 65 or older. The explanatory variable is a measure for the average LOC over all available observations. The effects are estimated using a linear regression model. Columns 4 and 6 present the results for absolute count of years while columns 5 and 7 present the share of years in LF or employment of the total years labor force statuses are observed for the woman during this time-span. The results indicate a significant positive effect of a high LOC on lifetime labor force availability and activity. Women with a high LOC spent on average approximately 1.2 more years in the labor force (3.0%) and 1.5 more years in employment (3.6%) during this time.

4.4 Robustness checks

Omitted Variable Bias As has already been discussed in detail in Section 3.3, a drawback of the study at hand is that it does not rule out endogeneity in LOC due to omitted variables bias. In order to access the impact of additional unobserved factors on the estimation results, the approach proposed by Oster (2019) is applied. This method exploits the assumption that the bias from observed factors provides information about this unobserved bias, as it assumes a certain amount of proportionality between both biases and assesses the movements in coefficients and R-squared. Table 4 contains the results of this sensitivity analysis.

Comparing Columns (1) and (2) in Table 4 reveals that the estimated effect of the continuous LOC Factor on LF decreases from 0.028 in a linear probability model without any control variables, except time and region fixed effects, to 0.011 in the full specification, which includes all sets of control variables except the endogenous variables discussed in Section 4.2. Guided by the rule of thumb provided in Oster (2019), the maximum R2 (i.e., the R-squared from a hypothetical regression of the outcome on the treatment and both observed and all unobserved controls) is set to 1.3 times the R2 in the fully-controlled model for each of the estimations. The method is based on assumptions about the relative degree of selection on observed and unobserved variables (δ). δ = 1 would imply that observed and unobserved factors are equally important in explaining the outcome, while δ > 1 implies a larger impact of unobserved than observed factors. Column (3) contains the identified set of coefficients at δ = 1 which is [0.005; 0.011] for the continuous LOC factor and would thus still be positive even if we consider a set of potential unobserved factors which has an equal importance as the already very rich set of control variables in our full specification. Reassuringly, the identified set of coefficients only includes zero if \(\tilde{\delta }\) exceeds 1.73, meaning the unobserved factors would have to be nearly twice as important as the already included observed factors.

Similar robustness can also be identified for the binary indicators in Panel II of Table 4. Especially the estimated effect of a medium LOC is very robust with the identified set of coefficients only includes zero if the set of potential unobserved factors is over thrice as important as the already included observed factors.

Locus of Control As a second important set of sensitivity checks, the construction and imputation of LOC as explanatory variable is tested. Panel 1 of Table A.4 presents the results of four alternative forms of construction of the LOC factor, which have already been introduced in Section 3. The construction of the factor is robust against variations in the items considered in the factor predictions (columns (3) to (8)) as well as against the use of a simple index instead of the prediction based on the loadings from factor analysis (columns (9) and (10)).

Secondly, the timing of the LOC measurement and thus the imputation approach is tested for its impact on the robustness of the estimated results. As Preuss and Hennecke (2018) pointed out, there is a considerable risk of reverse causality or attenuation bias due to temporary measurement errors in the LOC. Using the same data from the SOEP, they found a significant negative short-run effect of exogenous job-loss on LOC for individuals who are still unemployed during the LOC interview. They conclude that this is likely to be driven by temporary state-dependent reporting in the LOC for unemployed individuals even though LOC can be assumed to be stable in the long-run. Due to the fact that employed and non-employed individuals are pooled in the present estimation sample, there might be a risk of biased results due to a measurement bias in LOC, which would, by definition, be greater in the group of non-participating women due to a higher share of non-employed individuals in this groupFootnote 13. In order to circumvent this measurement problem, two alternative approaches are implemented. Firstly, instead of the forward imputed LOC, a variable which averages all available LOC observations of an individual between 1999 and 2015 is used as the explanatory variable. This approach is likely to reduce the attenuation bias in the LOC due to temporary measurement errors to a minimum. The results of this alternative estimation are presented in columns (1) and (2) in panel II of Table A.4. The estimated effects increase in magnitude and remain statistically significant. It has to be noted that these alternative estimates nevertheless are again at risk of being biased by reverse causality, which is why the forward imputation is still the preferred imputation method. Thus, as a second robustness check, LOC is imputed from the first available LOC observation of an individual in the SOEP. In this alternative imputation LOC from 1999 if available, if not from 2005 and so on in order to go as far back in time as possible. Results in columns (3) and (4) show show that results are also robust against this change in the imputation method.

Using the average or first LOC nevertheless does not solve problems with reverse causality if the measurement error is selective, as women who are not employed in t have a higher probability to also be not employed in the periods before and after t. These women thus always report a lower LOC due to their non-activity on the labor market. Therefore, additionally the LOC observation during the closest employment or self-employment spell to t is used. The two conditions for imputing the LOC observation from a period t + x or t − x into t are that (a) LOC has to be observed in that year and (b) the woman is observed to be employed or self-employed in that year.Footnote 14 Nevertheless, this approach has one main caveat: by imputing from the closest employment spell, all women who are never observed in (self-)employment are lost. Never being observed in (self-)employment is highly endogenous to the model in line with the argumentation in Section 4.2. Columns (5) and (6) in panel II of Table A.4 thus check the effect of the LOC variable in the baseline model, using only the sample of women for which the LOC variable from the closest employment is observed. As expected, although still positive and significant, the estimated effect is now considerably smaller, indicating a problem with endogeneity in the observability of employment spells. Based on this reduced sample, columns (7) and (8) present the results for the alternative approach of imputation for the LOC factor. When using the reduced sample, the alternative LOC variable slightly increases the estimated effects. Thus, if the main estimations are at risk of being biased, this is likely to be a bias towards zero by attenuation.

Lastly, in addition to concerns with respect to measurement problems which might cause attenuation, the effect of the scale changes between 1999 and 2005 on the estimation results on the estimation results have been analyzed. This has been done by restricting the estimation sample to the period 2006–2018 and thus avoiding the use of any imputed values of LOC from 1999. The results in columns (9) and (10) show that estimation results are robust against this change too.

5 Effect heterogeneity

The influence of personality on participation can be assumed to crucially depend on the overall size of underlying participation incentives. If monetary and non-monetary incentives for either market or home production are very strong, the power of personality to affect participation probabilities may be comparably low. Thus, the estimated effects are expected to be highly heterogeneous with respect to, for example, overall size of the available household income or the monetary and non-monetary utility from home production as well as with respect to underlying differences in social norms of working.

Consequently, in this section, the heterogeneity of the estimated effects with respect to the family status (i.e., existence of a partner and children in the household) as well as with respect to underlying differences in social norms of working (represented by region of living and cohort indicators) is considered. Nevertheless, a major drawback of this heterogeneity analysis is the endogeneity of these variables and the high likelihood of them being correlated with other potentially important unobserved factors such as for example latent values and norms. The heterogeneity analysis at hand, thus, only provides additional evidence and has to be interpreted with caution.

Since not only β2, i.e., the marginal effect of loc, is regarded to be heterogeneous, the heterogeneity is examined using fully separated models for the different subgroups SGit:

In order to reduce problems with selection into these sub-groups depending on LOC, LOC is standardized and cut into terciles for each sub-group separately such that women are always compared to women in the same sub-groupFootnote 15.

Family Status and Children Table 5 presents the results for the sub-samples based on family status and existence of biological children under the age of 16. These subgroup analyses correspond to the supposed heterogeneity of the effect of LOC on participation probabilities with respect to underlying monetary and non-monetary incentives and disincentives to work, driven by the existence of partners and children in the household. Participation shares in the sub-samples are reported in the bottom row of the table and already indicate the different levels of incentives for the different groups with incentives for working being especially high in the groups of women without partners in the household (columns 4 and 5), likely due to the absence of a unconditional baseline household income provided by the partner. But also the absence of children in the household increases participation probabilities, likely due to lower monetary and non-monetary incentives for home production such as childcare costs or direct non-monetary utility from spending time with your children.

Looking at the estimated average marginal effects for the separate groups, we can see that the effect is, in large part, driven by cohabiting women. Cohabiting women with a medium (high) LOC are, on average, ceteris paribus 2.2–3.5 (2.3–2.8) percentage points more likely to be in the labor force than cohabiting women with a low LOC, depending on whether they have children under 16 in the household (column 6 and 7). The effects differ only marginally between cohabiting women with and without children, with the non-linearity of the LOC effect being stronger for women without children.

For non-cohabiting women, the effect is insignificant and close to zero if no children are present in the household. However, in the subgroup of non-cohabiting women with children under 16, i.e., single mothers, the effect of a medium LOC is positive and significant on the 10% level. Single mothers with a medium LOC are, on average, ceteris paribus 2.1 percentage points more likely to be in the labor force than single mothers with a low LOC. Nevertheless, a high LOC does not significantly increase the probability of being in the labor force for single mothers.Footnote 16

All these results support the theoretical idea that the effect of LOC on participation probabilities strongly interacts with underlying incentives and disincentives to work. If the monetary incentives for market production, such as in the case of single women without children,Footnote 17 already considerably exceed the decision threshold, personality and preferences have no power to affect the participation decision.Footnote 18

There is no clear evidence for the theoretical idea that an internal LOC might be associated with a lower participation probability for mothers due to considerations about their own influence on children’s outcomes, but this consideration might be reflected in the non-linearity of the effects.

Social Norms of Working In additional to budget constraints, a woman’s decision making might also be constrained by prevailing non-monetary utility from participation such as social norms of working. If, for example, one group of women is exposed to strong social norms for working and another group is exposed to weak social norms of working, even women in the first group who individually gain lower marginal utility from participation (i.e., external women) still have a high probability of participating as the marginal utility from participation is already considerably high. This is also in line with the idea that, for example, for men the social norms of “being the breadwinner” are expected to be very strong in general and thus independent from their LOC (see e.g., Bertrand et al., 2015, Charles et al., 2018, Killingsworth & Heckman, 1986, Knabe et al., 2016).Footnote 19 The same might be true for groups of women who are subject to very strong social norms of working. For them, the harm from staying at home exceeds the gains from participation independent of their personality.

As prevailing social norms of working are unobserved and no direct measure for them exists in the data at hand, the analysis relies on three different discontinuities of social working norms already observed in the earlier literature: East and West Germany, urban and rural regions and age cohorts. Table 6 presents the results of this heterogeneity analysis. The estimation results again are presented for fully separated models and LOC is predicted and standardized separately within each group.

Firstly, heterogeneity can be expected with respect to differences between the eastern and western parts of Germany. Due to the long-term socialist political influence in the former GDR, the east of Germany has a longer tradition of women’s participation in the labor force.Footnote 20 As we would nevertheless also expect the rurality of the region to play a role for the prevalence of social working norms, we distinguish between 4 types of regions: West urban, West rural, East urban and East ruralFootnote 21. As the direct marginal utility from participation is expected to be higher for eastern German women as well as women in urban areas, the absolute effect of LOC on participation probabilities is expected to be lower.

The observation numbers (columns 1 to 4 in bottom panel of Table 6) support this assumption especially with respect to East versus West Germany. The participation probability is with around 80% distinctly lower in the west of Germany than in the east of Germany (approx. 88%) but largely independent from whether the woman lives in a rural or urban area. In line with the assumption the results reveal that the significant positive marginal effect of a medium and a high LOC is mainly observable for women in the rural areas in the west of Germany. The effect for urban regions in the West is still significant but distinctly lower. While the effect for rural regions in the East is, as expected, essentially zero, we do see some effects for a high LOC in urban regions in the East. Nevertheless, these effects are driven by women in Berlin who make up 36% of the women in the East German, urban regions sampleFootnote 22. A potentially strongly connected explanation for the regional differences could be underlying differences in child care availability in East and West as well as rural and urban regions, which could also explain the specific case of Berlin. Non-monetary and monetary factors can, thus, not be cleanly separated.

Additionally, based on the continuous decrease in the importance of traditional gender roles over time in almost all modern Western societies (see e.g., Goldin, 2006), women in later cohorts are assumed to be more affected by a generalized social pressure to be economically independent from external forces than women of earlier cohorts (Heim, 2007). For the former, the marginal utility from participation can be assumed to be higher than for the latter. They might therefore have a higher participation probability independent from LOC. Thus, columns 5 to 7 of Table 6 present the results of the estimations. The cutoffs for the manifestations of the birth cohort indicator “early”, “middle” and “late” were generated based on the terciles of year of birth in the full estimation sample, i.e., P(33) = 1958 and P(66) = 1968, in order to obtain groups of approximately similar size. The results indicate a strong heterogeneity of the effect with respect to cohort. The distinct marginal effects of a medium and high LOC on participation probabilities can mainly be observed for women from the early cohorts, i.e., born before 1958 (column 5). The effect is distinctly lower for both the women in the medium as well as in the latest cohorts.

6 Conclusion

How do women make decisions about their labor force participation at a given point in time and what factors determine heterogeneity in participation probabilities between and within genders? This is a question economists have already been interested in for many years of fruitful theoretical and empirical research. Nevertheless, we are still far from solving the puzzles within this long-lasting “hot topic” in labor economics. This paper contributes to this research by theoretically and empirically discussing the role of the personality trait locus of control for differences in participation probabilities between women. Due to the rich facets of the construct LOC, it can be assumed to influence multiple components of a woman’s maximization problem when choosing the optimal labor force status. Existing literature predicts that LOC plays a crucial role in independence preferences and expected returns to investment decisions. Therefore, a positive relationship between LOC and the marginal utility from participation, through subjective monetary and non-monetary gains, is expected.

Based on the theoretical considerations, a reduced form estimation of the relationship between LOC and a woman’s probability of being available to the labor market is conducted. The analysis finds that internal women, i.e., women who believe in the importance of their own efforts for life outcomes are, on average, 13 percent more likely to be available to the labor force. Nevertheless, the relationship is found to be non-linear with especially strongly external women having a significantly lower likelihood of participation.

LOC thus adds explanatory power to the participation decision above and beyond traditional socio-economic factors as well as other preference measures. Hence, the paper significantly adds to the existing economic literature on female labor force participation as well as the important economic consequences of LOC by suggesting and empirically identifying distinct behavioral implications of LOC in the participation decision. Hence, the paper primarily contributes to the investigation of the psychological black box behind female labor force participation and, additionally, broadens the knowledge on the economic importance of LOC.

Additionally, a heterogeneity analysis identified an interesting sensitivity of the effect with respect to given monetary constraints as well as prevalent social working norms. This suggests that inherent traits, preferences and tastes are only able to inform participation decisions if the underlying budget constraints are fulfilled and if the decision-making is not constrained by exogenously imposed social norms. It seems natural to argue that this is not a phenomenon which is specific to LOC, but very likely also translates to other measures of psychological traits and economic preferences.

The identified role of LOC for a woman’s decision-making process as well as the prevalent importance of exogenous constraints in the relationship has crucial implications for the widespread political discourse about low labor force participation rates of women. When discussing and evaluating political measures targeted at increasing participation rates, such as active labor market policies, quotas or childcare availability, it is therefore extremely important to understand the boundaries of monetary incentives set by latent psychological characteristics. Considerations about the effectiveness of active labor market policies need to be aware of the component in individual decision making which cannot be influenced by monetary incentives, as it is based on inherent personal attributes and preferences for either participation or home production. Given the knowledge about stability of personality traits in adulthood, we might not be able to influence these aspects of women’s decision making at all. Nevertheless, the results from the heterogeneity analysis also illustrate that preference-based decision making is enabled or bounded by exogenous monetary and non-monetary constraints leading to a situation in which only a selective group of women is able to make relatively unconstrained decisions about their labor force participation. Reducing these constraints would presumably raise a woman’s welfare as her freedom of choice is increased.

Data availability

Publicly available data.

Code availability

Replication code available from authors upon request.

Notes

See Cobb-Clark (2015) for detailed discussion of the concept as well as an overview of the literature on LOC in labor economics.

LOC might have a direct effect on the household type a woman is living in if e.g., internal women are more prone to leaving the parental household and thus less likely to live in multi-generation households. This might lead to sample selection issues if these household are excluded from the estimation sample. Table S.3 in the Supplementary Material analyzes this association and results in column (1) and (2) indeed show a weak negative connection between the continuous measure of LOC and the probability to live in a multi-generation household. Nevertheless, the estimation results are robust against the inclusion of multi-generation households into the estimation sample (columns (3) and (4)).

In line with Specht et al. (2013), this process preserves the relative differences between individuals. The process results in values of 1, 3, 5 or 7 such that a ‘1’ on the 1999 four-point scale, for example, becomes a ‘7’ on the 2005–2015 seven-point scales. The robustness of results with respect to this is checked in Section 4.4.

A scatterplot of the loadings can be found in Fig. S.1 in the Supplementary Material.

The exclusion of items 4 and 9 is in line with the literature and supported by Specht et al. (2013). The exclusion of item 6 is specific to this paper as the near-zero loading seems to be driven by the sample of women while earlier studies have found a low but negative loading (see e.g., Caliendo et al., 2019, Preuss and Hennecke, 2018).

Sensitivity checks include a re-estimation of the results using this simple index. The results are found to be robust against this variation and can be found in Section 4.4.

Registered unemployed women who indicate that they were not actively searching for work in the last 4 weeks are coded to “not participating” while women who were originally coded as “not working” but indicate that they actively searched for a job, have the unconstrained intention to work and are ready to immediately start working are coded to “participating”.

Due to restrictions in the data availability more detailed geocodes are not available to the author but the model has been checked for sensitivity against the use of regional fixed effects on the level of local planning regions (Raumordungsregionen) at an earlier stage and all estimated effects were robust.

For more information on the scales see Andersen et al. (2007). The scales are surveyed biennially since 2002 and are thus imputed into other years from the closest observation while always preferring forward imputation.

Pregnancy is a generated variable based on observed childbirth in the 9 months after the interview.

Unearned household income is approximated by subtracting the reported labor net income as well as individual unemployment insurance payments from the reported net household income. The variable is thus assumed to capture all earnings which are not generated through labor force participation.

A women is assumed to spend a full year in a certain labor force status if she only reports one spell during a certain year. If she reports multiple spells during one year, she is assumed to have spent an equal share of the year in either spell and consequently the value (1\number of spells) is added to the counter.

While in the group of participating women potentially only some of the women, i.e., those who are unemployed, might have a state-bias in their observed LOC, the share is expected to be greater in the group of non-participating women as 100% of women in this sample might be affected by such a state-bias.

Backwards imputation is allowed to avoid problems with sample size. This is based on the assumption that, besides measurement bias in LOC through non-employment, non-employment has no long-term effect on LOC based on the findings in Preuss and Hennecke (2018).

Nevertheless, the use of within group standardization of LOC (group specific tertile groups), might again restrict absolute comparability of results across groups, especially if distributions differ across groups: Women reporting the same LOC may be in the bottom of one distribution, but in the middle of another. The sensitivity of the results to the within-group definition of LOC has been checked and results do not change if instead an across-group distribution is used.

Table S.4 in the Supplementary Material also provides analog estimation results for mothers depending on the age of their children. Women with pre-school and young school children (until the age of 12) exhibit the largest effects (columns 1 to 4).

Consideration about monetary constraints do not fully apply for single mothers with young children. In German law, employment is, among others, not “reasonable” if this employment would, for example, endanger the upbringing of children. As is regulated in §10 SGB II, this applies to children under the age of 3. Hence, these single mothers do have the opportunity to choose home production and receive social transfers as an equivalent to partners income.

These findings are supported by an additional heterogeneity analysis with respect to available family income presented in Table S.5 in the Supplementary Material. Family income is approximated by subtracting the reported labor net income as well as individual unemployment insurance payments from the reported net household income. The variable is thus assumed to capture all earnings which are not generated through own labor force participation.

In an additional analysis, presented in Table S.6 in the Supplementary Material, we replicate the results in our main analysis Table 2 for the sample of men and find significant positive but distinctly lower effects.

The socialist system was characterized by a strong emphasis on the dual-earner/state-carer system of family labor supply, i.e., an extremely high levels of female labor force participation in combination with an extensive system-level organization of family-support structures and child care (see e.g., Braun et al., 1994, Rosenfeld, Trappe & Gornick, 2004).

The indicator for rural vs. urban settlement is based on spatial categorization provided by the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR, 2020). Urban settlements include all counties which have at least a population density of 150 inhabitants per km2 or include at least one large city with 100.000 inhabitants or more.

A more detailed sensitivity analysis with respect to women in Berlin as well as the main estimation results when Berlin is excluded from the sample can be found in Table S.7 in the Supplementary Material. Estimation results for the main analysis are robust to this exclusion.

References

Akerlof, G. A., & Kranton, R. E. (2000). Economics and identity. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115, 715–753.

Almlund, M., Duckworth, A. L., Heckman, J., & Kautz, T. (2011). Personality Psychology and Economics. In E. Hanushek, S. Machin, and L. Woessmann, editors, Handbook of the Economics of Education, volume 4, chapter 1, pages p.1–181. Elsevier.

Andersen, H. H., Mühlbacher, A., Nübling, M., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2007). Computation of Standard Values for Physical and Mental Health Scale Scores Using the SOEP Version of SF-12v2. Schmollers Jahrbuch - Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 127, 171–182.

Angrist, J. D. (2002). How Do Sex Ratios Affect Marriage and Labor Markets ? Evidence from America’ s Second Generation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 997–1038.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. S. (2008). Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press.

BBSR (2020). Laufende Raumbeobachtung—Raumabgrenzungen, Städtischer und Ländlicher Raum. Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development, Online Resource. https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/forschung/raumbeobachtung/Raumabgrenzungen/deutschland/kreise/staedtischer-laendlicher-raum/kreistypen.html?nn=2544954 (Accessed February 23 26, 2021).

Berger, E. M., & Haywood, L. (2016). Locus of control and mothers’ return to employment. Journal of Human Capital, 10, 442–481.

Bertrand, M., Pan, J., & Kamenica, E. (2015). Gender Identity and Relative Income Within Households. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130, 571–614.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2007). Changes in the labor supply behaviour of married women: 1980–2000. Journal of Labor Economics, 25, 393–438.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2017). The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55, 789–865.

Braun, M., Scott, J., & Alwin, D. F. (1994). Economic necessity or self-actualization? Attitudes toward women’s labour-force participation in East and West Germany. European Sociological Review, 10, 29–47.

Caliendo, M., Fossen, F., & Kritikos, A. S. (2014). Personality characteristics and the decisions to become and stay self-employed. Small Business Economics, 42, 787–814.

Caliendo, M., & Uhlendorff, A. (2015). Locus of control and job search strategies. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97, 88–103.

Caliendo, M., Cobb-Clark, D. A., Hennecke, J., & Uhlendorff, A. (2019). Locus of control and internal migration. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 79, 1–19.

Carton, J., & Nowicki, J. (1994). Antecedents of individual differences in locus of control of reinforcement: A critical review. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 120, 31–81.

Charles, K. K., Guryan, J., & Pan, J. (2018). The Effects of Sexism on American Women: The Role of Norms vs. Discrimination. NBER Working Paper Series No. 24904.

Cobb-Clark, D. A. (2015). Locus of control and the labor market. IZA Journal of Labor Economics, 4, 1–19.

Cobb-Clark, D. A., & Schurer, S. (2013). Two economists’ musings on the stability of locus of control. The Economic Journal, 123, 358–400.

Cobb-Clark, D. A., & Tan, M. (2011). Noncognitive skills, occupational attainment, and relative wages. Labour Economics, 18, 1–13.

Cobb-Clark, D. A., Kassenboehmer, S. C., & Schurer, S. (2014). Healthy habits: The connection between diet, exercise, and locus of control. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 98, 1–28.

Coleman, M., & DeLeire, T. (2003). An economic model of locus of control and the human capital investment decision. Journal of Human Resources, 38, 701–721.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334.

Devereux, P. J. (2004). Changes in Relative Wages and Family Labor Supply. The Journal of Human Resources, 39, 696–722.

Eissa, N., & Liebman, J. B. (1996). Labor Supply Response to the Earned Income Tax Credit. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111, 605–637.

Fortin, N. M. (2015). Gender Role Attitudes and Women’s Labor Market Participation: Opting-Out, AIDS, and the Persistent Appeal of Housewifery. Annals of Economics and Statistics, 117/118, 379–401.

Fuenmayor, A., Granell, R., & Mediavilla, M. (2016). The effects of separate taxation on labor participation of married couples. An empirical analysis using propensity score. Review of Economics of the Household 2016 16:2, 16, 541–561.