Abstract

This paper investigates whether exposure to adverse experiences during childhood, such as physical and emotional abuse, affects the likelihood of unhealthy habits later in life. The novelty of our approach is twofold. First, we exploit the recently published data on adverse childhood experiences in 19 European countries from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement (SHARE), which enables us to account for country-specific heterogeneity and investigate the long-term effects of exposure to adverse early-life circumstances (such as smoking, drinking, excess weight and obesity) on unhealthy lifestyles later in life. Second, we estimate the effect of childhood trauma on unhealthy lifestyles separately for European macro-regions using a clustering of countries emphasising cultural differences. Our results highlight the positive effect of exposure to adverse childhood experiences on the probability of unhealthy lifestyles in the long run. Harm from parents is associated with a higher probability of smoking in adulthood, while child neglect and a poor relationship with parents increase the probability of smoking later in life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

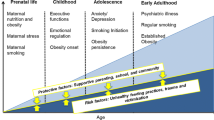

Research based on the Foetal Origin Hypothesis describes the human capital formation of the child through parental investments before and after birth, given the in-utero circumstances and pre- and postnatal environmental shocks. The literature in this field has grown significantly in recent years (see Almond et al., 2018, for a comprehensive overview). The main idea underlying the hypothesis is based that several health and socio-economic outcomes during the course of a lifetime may depend on early circumstances. Francesconi and Heckman (2016) find that the family environment in the early years of life together with parental investments (time and material goods invested in children) are critical determinants of human capital because they shape an individual’s initial stock of skills. The crucial role of the family in acquiring both cognitive and non-cognitive skills, the latter related to the socio-emotional dimension, has been outlined in several seminal studies (see, for instance, Cuhna & Heckman, 2008; Cunha et al., 2010). Recent contributions have shown that measuring the parental investment in the child solely in terms of financial expenditure is likely to be inadequate. For instance, Carneiro and Ginja (2016) suggest that the importance of financial resources in determining child outcomes has been overrated in the recent literature compared to the importance of parental care and mentoring. Nonetheless, the economic literature in the field has generally focused on “positive” investments, using measures/indices that capture the time spent by parents with children and the frequency and types of activities carried out together.

Rather than on positive investments, this paper focuses on specific parental (dis)investments in the form of emotional and physical abuse in childhood, i.e., physical harm from parents or third parties and child neglect. We explore their impact on health-related outcomes later in life. This set of adverse circumstances is commonly included in the epidemiological and psychological literature among Adverse Childhood ExperiencesFootnote 1 (hereafter ACE). They may have a strong emotional impact that persists throughout life and may influence an individual’s choices and/or behaviour.

A great deal of the literature has shown a significant relationship between ACE and health and health-related behaviour over the life course (see, for example, Anda et al., 1999; Anda et al., 2002: Ford et al., 2011; Dube et al., 2002; Case et al., 2005, Gunstad et al., 2006; Bellis et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2019). The association between ACE and health-related behaviours may have important economic and policy implications (Abegunde et al., 2007; Yach et al., 2004). Unhealthy behaviours are among the main risk factors that determine the onset of serious pathologies such as cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders and various forms of cancer, with significant economic and social costs (Elwood et al., 2013; Costa-Font & Gil, 2005; Sturm, 2002). Therefore, understanding the factors that influence such behaviours is of major importance if measures are to be devised to prevent them. Most of the existing contributions on the topic, however, are based on rather small samples and case studies, generally at the national or even the regional-community level, so the results cannot be scaled up to the population level and cannot be used for cross-country comparison.

The novelty of the approach adopted in this paper is twofold. First, the use of recent data from the Survey on Health, Ageing and Retirement (SHARE) enables us to take one step forward by exploiting the variability of the long-run effects of ACE on a set of (un)healthy behaviours, such as smoking, drinking, excess weight and obesity, both between countries and between generations, drawing on data on individuals in eighteen European countries (plus Israel), from different birth cohorts (from the 1930s to the 1970s). Second, unlike the existing literature in the field, we estimate the effect of childhood trauma on unhealthy lifestyles separately for European macro-regions using a clustering of countries emphasising cultural differences. More precisely, following Mensah and Chen’s (2013) Global Clustering of Countries by Culture, we group countries into four different clusters, i.e.: Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark and Estonia), Germanic countries (Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium and Luxembourg), Latin countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, and Israel), and Eastern European countries (Croatia, Greece, Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovenia).

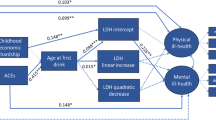

The presence of endogeneity due to self-selection and probable reverse causality in the relationship between adverse childhood trauma and unhealthy behaviours later in life may make identifying a causal link between ACE and unhealthy behaviours more difficult. To account for potential endogeneity, we match each individual who was exposed to ACE (the “exposed/treated”) with an individual who was not (the “control/untreated”) for every characteristic known to be associated with trauma and unhealthy behaviours (Caliendo and Kopeinig, 2008). This matching was accomplished through the use of propensity score matching, as formalised by Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983). The empirical strategy adopted in this paper represents a novel element since most of the existing literature relies on associations between childhood conditions and unhealthy behaviours. Overall, our findings confirm the important long-term effects of exposure to ACE on the outcomes (unhealthy behaviours) considered, highlighting some interesting differences by macro-region. Harm is associated with a higher probability of smoking in adulthood, while child neglect and a poor relationship with parents increase the probability of smoking later in life. Physical abuse has a significant effect on heavy drinking in Eastern countries, while in Nordic countries emotional neglect is a significant determinant of alcohol abuse. In the case of obesity, physical harm has been confirmed as a significant predictor for individuals from Eastern European countries.

The paper is organised as follows. Section “Data and Variables” describes the dataset and the variables used in the empirical analysis. Section “Empirical Strategy” explains the estimation strategy and Section “Results” presents the main results. Section “Conclusion” concludes.

2 Data and variables

Individual-level data, as used in this study, are drawn from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). SHARE is a multidisciplinary, longitudinal survey on ageing which focuses on individuals aged 50+ and their spouses.Footnote 2 The survey contains both regular and retrospective waves (SHARELIFE). The regular rounds collect information on an individual’s current situation such as health, employment, social network/relations, accommodation, economic situation/assets, behavioural risks and expectations. In addition, two survey rounds add retrospective information on multiple dimensions of the respondent’s past (health, healthcare, accommodation, career, household situation and performance at school during childhood, number of children, childbearing for women, emotional experiences in early life, relationship with parents, adverse childhood experiences, etc.).

What makes SHARE data particularly suited for the purposes of our analysis is the ability to link the information on the current situation of respondents to retrospective childhood/adulthood data. The information on lifestyles such as smoking behaviour over the lifespan, alcohol abuse and obesity in adulthood, as well as personal characteristics (age, gender, and education) are taken from regular waves, while the retrospective childhood conditions, the respondent’s household situation and recently released data on the quality of the parent-child relationship and early-life emotional experiences are drawn from SHARELIFE. The final sample includes all respondents participating in at least one regular SHARE wave (between Waves 4 to 6) and in the SHARELIFE interview of Wave 7. Individuals who entered the survey before Wave 4 are excluded because of the lack of information about their adverse early life experiences. We obtain a data set covering18 European countries (Austria, Germany, Sweden, Spain, Italy, France, Denmark, Greece, Switzerland, Belgium, Czech Republic, Poland, Luxembourg, Hungary, Portugal, Slovenia, Estonia, and Croatia) and Israel.

In order to take the prevailing culture into account, we follow the results of the GLOBE study (Global Leadership and Organisational Behaviour Effectiveness 2004, and 2007) and Mensah and Chen’s (2013) subsequent extension (Global Clustering of Countries by Culture),Footnote 3 and group the countries in our sample into four clusters, namely: Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, and Estonia), Germanic countries (Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, and Luxembourg), Latin countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, and Israel), and Eastern countries (Croatia, Greece, Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovenia). We chose to refer to this type of culture-based clustering since a number of studies state that cultural features have an important influence on parent-child interactions (Coltrane, 2004, Morman & Floyd, 2002, Saracho & Spodek, 2008). After correcting for missing values, the final sample includes 26.877 observations, which are split up as follows: 5024 in Nordic countries, 8033 in Germanic countries, 7031 in Latin countries, and 6789 in Eastern European countries.

2.1 Outcome variables

In our analysis, we explore the relationship between adverse childhood conditions and a set of unhealthy behaviours, such as smoking, drinking, excess weight and obesity over the lifespan.

In evaluating smoking behaviour, we use information elicited from regular SHARE waves, considering two variables. In order to evaluate the impact that ACE may have on the probability of starting to smoke, a dummy is used to indicate whether the respondent has ever smoked on a daily basis at any time. For individuals who say they are current smokers or have smoked on a daily basis, we consider a variable that records the number of years of smoking. About 44% of respondents in our sample say they smoked on a daily basis at some stage in their life. The percentage of men is nearly 57%, while for women it is about 34%. If we focus on the persistence of smoking in terms of the number of years as a smoker, men tend to smoke for longer periods (on average 27 years) than women (23 years). Looking at macro-regions, the highest percentage of individuals reporting smoking on a daily basis is in Nordic countries (48%), followed by Germanic (46%), Eastern European (42%), and Latin countries (41%). These outcomes are unconditional and may depend on age and cohort, still the differences are quite remarkable: the econometric analysis below is an attempt to unravel the role of the different variables.

Regarding alcohol abuse, a dummy variable is used starting from the intensity and the frequency with which respondents drink alcoholic beverages in adulthood. Specifically, we consider the following question (available in the regular SHARE waves): “In the last three months, how often did you have six or more units of alcoholic beverages on one occasion? 1. Daily or almost daily; 2. Five or six days a week; 3. Three or four days a week; 4. Once or twice a week; 5. Once or twice a month; 6. Less than once a month; 7. Not at all in the last 3 months”. The heavy drinking dummy has value 1 if respondents declare a consumption of six or more drinks on the same occasion (i) daily or almost daily; (ii) five or six days a week; (iii) three or four days a week; (iv) once or twice a week, and 0 otherwise. About 12% of the respondents in our sample can be considered heavy drinkers according to the above definition. This proportion differs between men and women: rates of self-reported heavy drinking are about 18.4% for men and 6.3% for women. In terms of regional disparities, Germanic countries have the largest percentage of heavy drinkers (about 17%), while Latin countries have the lowest (6%).

We measure adult excess weight and obesity using information on the body mass index (BMI) elicited in the regular waves of SHARE. BMI is calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by the square of body height in metres (kg/m2). In line with the medical indications that BMI-for-age should only be used for children and teenagers (below the age of 20) and with the recent literature (e.g., Feigl et al., 2019; Otang-Mbeng et al., 2017; Devaux & Sassi, 2015), we use a single threshold for defining the overweight and one cut-off for obesity for the individuals in our sample (https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/).Footnote 4 In line with the World Health Organisation definition of excess weight and obesity, we consider that an individual is obese with a BMI of 30 or more while a person is overweight with a BMI of 25 or more. In order to evaluate the impact that ACE may have on the probability to be overweight or obese later in life, we first use a dummy with value 1 when the respondent has a BMI of 25 or more, and 0 otherwise. The overweight and obese account for 65.68% of our sample. More men than women are overweight or obese (70.3% versus 62.19%). These percentages reflect recent European statistics,Footnote 5 confirming a high prevalence of overweight people and obesity especially in the adult population. Second, we focus on the most severe form of being overweight, i.e. obesity, by creating a dummy variable that has value 1 for an individual with a BMI of 30 or more and 0 otherwise. About 24.5% of the overall sample risks obesity, and this percentage slightly differs between genders (men 23.47%; women 25.41%). There are significant differences in the percentages of obese people between macro-regions; interestingly, Eastern Europe has the highest percentage of obese people (27%), followed by about 23% in Nordic countries, 21% in Germanic countries, and about 18% in Latin countries.

2.2 Adverse childhood experiences

Our key explanatory variables are related to adverse early-life experiences. SHARELIFE asks respondents to provide information on exposure to child neglect and childhood physical abuse, from mother, father or a third party. In relation to physical abuse from the mother or father, the questionnaire asks:

-

1.

How often did your mother/your father push, grab, shove, throw something at you, slap or hit you? 1. Often 2. Sometimes 3. Rarely 4. Never

In addition, the survey also collects data on child physical abuse by third parties:

-

2.

How often did anybody else physically harm you in any way? 1. Often 2. Sometimes 3. Rarely 4. Never.

Albeit different from the items used in epidemiological research, we consider an additional indicator for child neglect derived from the following question:

-

3.

How much did your mother/your father (or the woman/man that raised you) understand your problems and worries? 1. A lot 2. Some 3. A little 4. Not at all

Finally, we also include among the explanatory variables the self-reported quality of the relationship with each parent:

-

4.

How would you rate the relationship with your mother/your father (or the woman/man that raised you)? 1. Excellent 2. Very good 3. Good 4. Fair 5. Poor.

The literature in the field distinguishes between various subtypes of neglect based on the dimension in which parents prove to be inadequate. As regards emotional neglect, Straus et al. (1997), for instance, associate emotional neglect with parental failure to provide “affection, companionship, and support”. They point out that this form of early adverse experience may have important social and psychological implications, which may even be more damaging than some types of psychologically “abusive” attention (such as hostile and verbally abusive parents). However, there is a large heterogeneity in measuring child neglect in surveys (see Stoltenborgh et al. (2013) for a comprehensive overview). With data from the Recruitment Assessment Program study, Young et al. (2006) use one item to assess emotional neglect (“You felt loved”), while Straus et al. (1997) use a short version of “The Neglect Scale” and approximate emotional neglect from the scores to the following statement: “did not help me when I had problems”. Finally, the refined CDC-Kaiser Permanent ACE Study asks a series of questions in the sphere of emotional neglect, such as “You knew there was someone to take care of you and protect you?”, “Your family was a source of strength and support?”, “People in your family looked out for each other?”, “There was someone in your family who helped you feel important or special?” and “You felt loved?”. All these measures have been validated as good instruments to measure emotional neglect. Although the above-reported questions on emotional neglect in SHARE (lack of understanding or poor relations) slightly differ from the questions in other ACE-specific studies, we believe that, from a conceptual point of view, they are informative and aligned with the existing proxies for the presence or absence of emotional neglect.

In order to obtain a set of adverse childhood experience variables, we first recode the answers into dichotomous variables, where a value of 1 indicates that the individual was exposed to a negative experience in early life. We consider that an individual experienced physical abuse from either the mother or the father if she/he answers ‘1. Often’ or ‘2. Sometimes’ to question 1. We treat question 2 in the same manner to capture physical harm from another person. A situation of ‘child neglect’ is shown by answers ‘3. A little’ or ‘4. Not at all’ to question 3. The relationship with the mother/father in childhood is rated 1, i.e., problematic/negative, if the respondent answers ‘4. Fair’ or ‘5. Poor’ to the last question.

We then create a set of dummy indicators with value 1 if respondents have experienced (i) physical harm from father/mother/other parties, (ii) child neglect from either the mother or the father, (iii) a poor relationship with either parent, and 0 otherwise.

3 Empirical strategy

Identifying a causal association between ACE and unhealthy behaviours may be complicated by the presence of endogeneity due to self-selection and potential reverse causality in the relationship between the exposure to trauma in childhood and unhealthy behaviours over the lifespan. The treatment assignment (i.e. exposure to ACE) is not randomised among individuals and the outcome of interest (unhealthy lifestyles) may be biased by differences in the characteristics that influence the selection into the “ACE status”. For instance, children may have been more exposed to adverse circumstances because of a lower family SES.

This potential endogeneity problem can be corrected by matching each individual who experienced ACE (the “exposed/treated”) with an individual who did not (the “control/untreated”) on each characteristic known to be associated with trauma and unhealthy behaviours (Caliendo & Kopeinig, 2008). This matching was performed by using a propensity score matching, as formalised by Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983).

Propensity score matching produces two balanced groups, one of individuals exposed to ACE, and one of individuals not exposed to ACE: the resulting score substitutes a collection of confounding variables with a single covariate that is a function of all the variables. By summarising the intrinsic characteristics that could generate distortions, propensity scores use a matching procedure to allow for comparisons between the treated and control groups, alleviating the endogeneity problem. Formally, this methodology models the probability of being “treated” (i.e., exposed to ACE) ei(x) for each respondent conditional of observable individual characteristics (X):

where Di is an indicator variable that individual i belongs to the “treatment” group, i.e., he/she was exposed to ACE. The common support is considered restricting the attention to the set of data points belonging to the intersection of the supports of the propensity score distribution among treated and controls. Outside the common support, no counterfactual exists.

The average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) is measured by the difference in unhealthy lifestyle variables; the identification of ATT relies on the validity of the Conditional Independence Assumption (CIA), namely that potential treatment outcomes are independent of the assignment mechanism for any given value of a vector of observable characteristics, (X), i.e., selection-on-observables (Ichino et al., 2008). In our case, CIA implies that any disparities in lifestyles between two individuals whose observable traits are as comparable as possible can be attributed to the effect of ACE.

3.1 The propensity score

As a first step, a set of probit models were set up on which to base the scores: the dependent variables were binary variables with value 1 for respondents who report experiencing unhealthy behaviours – such as smoking, drinking, excess weight and obesity over the lifespan - and 0 otherwise.

This set of probit models controls for a rich set of information on an individual’s socio-economic status (SES) in childhood, i.e., the work status of the respondent’s father (whether or not employed), the number of books at home, the number of rooms at home, household size, the occupation of the main breadwinner (white/blue collar) and health status of the respondent aged ten. For the number of books at home, we generate a dummy indicator equal to 1 if the respondent had more than 100 books at home at age ten, and 0 otherwise. For self-assessed childhood health (SAH), SHARE asks the following question: “Would you say that your health during your childhood was in general excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”. SAH was therefore measured on a five-point scale from “excellent” (score 5) to “poor” (score 1) and treated as an ordered categorical variable. We dichotomised the SAH into a binary variable with value 1 if individuals declare that their health during childhood was excellent, very good or good, and 0 otherwise. In addition, we include a dummy variable with value 1 if the respondent’s family moved due to financial hardship during his/her childhood. Moreover, to capture the household structure in which respondents grew up, we include three dummy variables regarding siblings. Specifically, (i) a dummy indicator with value 1 if interviewees report having any siblings, and 0 for those who report having none, (ii) two dummies identifying the birth order – if the individual is the first or last born (reference category: middle-born child).

Along with information on childhood characteristics, we also include information on the educational level of the parents. Specifically, we generate a dummy variable with value 1 where either the father or mother of respondents completed high school, and 0 otherwise.

To capture possible long-run trends in our outcome variables, we further consider a set of indicators for the birth cohort. Since the view of smoking or drinking as negative health behaviour may have differed substantially between younger and older cohorts, we distinguish between three generations, namely the “Silent Generation” (born 1926–1945), “Baby Boomers” (born 1946–1965), and the “X Generation” (born 1966–1980) (Di Novi & Marenzi, 2009).Footnote 6

In addition, to control for a potential business cycle effect operating through economic conditions, in all specifications we consider a dummy indicator for undergoing at least one period of recession (defined as three consecutive years of negative GDP growth)Footnote 7 from age 1 to 17, which coincides with the reference period for reporting ACE. To account for unobserved country-specific effects, we include country dummies in all the regressions. Finally, to take into account migration episodes over the lifespan, we include a binary variable with a value of 1 to indicate an individual who reports living in a country different from his/her native country.

For smoking, we additionally restrict our sample to individuals who say they are current smokers or have smoked on a daily basis, and use the total number of years of smoking as a dependent variable in order to estimate the effect of ACE on the persistence of smoking.

Once the propensity scores were calculated, we proceeded with statistical matching to form ‘twin data’ that differ in terms of “ACE status” and not in terms of any of the other observed characteristics. Since the sample consists of comparatively few individuals who were exposed to ACE in relation to many untreated individuals, Kernel matching was chosen as the matching algorithm. Footnote 8

4 Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of adverse childhood experience variables (ACE) separately by gender and macro region in Europe.

Male respondents in Eastern Europe seem to have experienced more physical harm (from mothers, fathers or other parties) than individuals from other regions. On average, individuals in Central Europe report less understanding and poorer relationships with parents than the other regions.

Comparing the means between genders, women suffer slightly less physical harm from anyone (i.e., either parent or someone else in or outside the family) in all European regions. In Northern and Central Europe, on average, women report less understanding from either parent and poorer relationships with parents than male respondents, while in Latin and Eastern European countries, both genders report better relationships with either the father or the mother.

Table 2 describes the prevalence of smoking, heavy drinking, excess weight and obesity separately for each ACE.

The percentages indicate a higher prevalence of smoking and obesity for each ACE considered. In the case of heavy drinking and excess weight, the incidence is greater for individuals exposed to harm from parents while there are no significant differences between those that have or have not experienced poor understanding from, or a poor relationship with, their parents.

The birth cohort is another source of variability in our data. Table 3 presents the prevalence of unhealthy behaviour by generation (silent generation, baby-boomers and X-generation) for individuals who experienced ACE versus those not exposed to adverse circumstances in early life.

Important differences between exposed and non-exposed people can be observed for the younger to generations (baby-boomers and X-generation), supporting the hypothesis that “smoke” is linked to “self-medicating efforts to cope with the negative effects of adverse childhood experiences” (Anda et al., 1999).

The interpretation of the above descriptive statistics, however, requires some caution due to a possible selection bias since the oldest cohort in our sample include individuals with better health prospects and, hence, a longer life expectancy.

4.1 Smoking and heavy drinking

Below, we present the results of our main empirical specifications. Table 4 shows the average effect of childhood trauma (ATT) on the probability of daily smoking and alcohol abuse.Footnote 9 The analysis is carried out separately for each macro-region considered. ATT was computed by adopting the Kernel matching method.Footnote 10 Only observations within the common support were used in the matching.

In general, our findings highlight a significant and positive relationship between adverse childhood experiences and the probability of smoking daily at some point in adulthood in all the macro-regions considered. The effect is significant both for males and females denoting no important differences between genders.

Physical harm appears not to have a significant effect on alcohol abuse in Nordic, Germanic, and Latin countries, while in Eastern European countries it increases the probability of heavy drinking by about 3.4%. Exposure to child neglect (little understanding) increases the probability of alcohol abuse by 2.7% in Nordic Countries while no significant effects are detected in other macro-regions. Interestingly, the experience of a poor relationship with parents is a strong predictor of alcohol abuse for the female subsample in Latin countries: the probability of heavy drinking for women residing in this macro-region who experienced a poor relationship with parents is 2% higher than women who did not experience a poor relationship with either the father or the mother. The effects of ACE on smoking behaviour, on the other hand, are stronger in Nordic and Germanic countries, especially among women.

Table 5 shows the results for the number of years a respondent has been smoking or smoked in the past.

Again, we find a significant and positive relationship between adverse childhood experiences and total years of smoking, with important differences among types of ACE. Exposure to physical harm (either from the mother, father, or someone else in or outside the family) significantly increases the number of years of smoking in all macro-regions, except Latin countries. Conversely, reporting a poor relationship with parents does not significantly affect the total years of smoking in any area, while emotional neglect has a strong impact on the persistence (number of years) of smoking in Germanic, Latin, and East European countries. Together with the results of Table 4, it is interesting to note that experiencing a poor relationship with either parent is a significant predictor of the probability of ever smoking daily, but it does not have a significant impact on the persistence of smoking.

4.2 Excess weight and obesity

Table 6 sets out the results for the probability of being overweight and obese later in life.

While ACE does not appear to have a substantial effect on excess weight in any macro-region, childhood trauma appears to have a major impact on the likelihood of being obese later in life. Unlike smoking and drinking, obesity can be regarded as a serious health hazard caused mostly by poor eating habits and lack of physical activity. Furthermore, research (e.g., Sturm, 2002; Sturm & Wells, 2001) shows that obesity is associated with extremely high rates of chronic illness, far higher than poverty and far higher than smoking or drinking.

Of the different types of ACE, physical harm is a significant determinant of obesity for individuals from Eastern European countries. Exposure to physical abuse increases the probability of obesity later in life by 4% in the whole sample reaching about 5% for the male subsample. In no macro-region do child neglect variables and experiencing a poor relationship with parents have a significant effect on the probability of being overweight or obese, except for a weak effect (significance at 10%) for obesity in the Germanic region.

5 Conclusion

Several recent studies have explored the importance of early life conditions in determining lifestyles and future health, especially in the epidemiological field. However, most studies are based on rather limited samples, generally at the national or even regional/community level, and cannot be easily generalised.

In this paper, we use recent European data from SHARE to analyse whether exposure to adverse experiences, such as physical abuse and emotional neglect, during childhood affects several unhealthy behaviours, i.e., smoking, drinking, and an unhealthy diet, leading to excess weight and obesity. Our results outline a significant and positive impact of early life trauma on the probability of adopting unhealthy behaviours later in life, highlighting some interesting differences between macro-regions. Exposure to physical harm is associated with a higher probability of smoking in adulthood, while child neglect and a poor relationship with parents have a positive impact on the probability of smoking later in life. Physical abuse has a significant effect on heavy drinking in Eastern European countries, while in Nordic Countries emotional neglect is a significant determinant of alcohol abuse. Regarding obesity, physical harm is a significant predictor for individuals from Eastern European countries.

The empirical evidence set out in this paper may have important policy implications. First, child abuse and neglect are serious issues since they can have important and lasting effects on an individual’s lifestyle and health throughout life, with a significant individual and social cost.

Policymakers should identify and pay particular attention to the disadvantaged portion of the population since these individuals may be considered less responsible for the observed outcomes than better placed individuals. Improving the quality of healthcare services necessary for trauma screening, for instance, may help to identify children at risk of poor health outcomes so they can undergo specific interventions in the hope that outcomes can be improved. Interventions may consist of economic support for families, family-friendly work policies or educative campaigns. Interventions targeted at improving childhood conditions have received a lot of attention in the United States recently, but less in Europe, where most studies have concentrated on the United Kingdom and ex-communist countries.

In relation to similar studies in the field, we recognise that this research has some limitations. First, ACE was retrospectively recalled in adulthood and may have been subject to recall bias and “colouring”. In this regard, Havari and Mazzonna (2015) assessed the internal and external consistency of the measures of childhood health and socio-economic status included in SHARELIFE wave 3 and found that overall respondents seem to remember their childhood conditions fairly well. Since the method used to collect retrospective information – the Life History Calendar – was also applied in Wave 7, we can plausibly assume that, overall, respondents have a fairly good recollection of their health status and living conditions between ages 0–15. Moreover, some studies note that ACE recollection is relatively accurate (e.g., Hardt & Rutter, 2004; Hardt et al., 2006; Campbell et al., 2014).

In addition, this analysis allows for future refinements such as including other potential confounders, including adverse events in adulthood, which may affect outcomes later in life.

Data availability

Available upon request/acceptance for publication.

Code availability

Available upon request/acceptance for publication.

Change history

24 August 2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

Notes

See, among others, Finkelhor et al. (2015).

The survey began in 2004 and is carried out every two years. It was initially implemented in 11 countries and then gradually extended, now to 28 countries (all European Union member states except Ireland, plus Switzerland and Israel).

The classification is based on a statistical model that includes five cultural dimensions: racial/ethnic distribution, religious distribution, the geographical proximity of the countries, major language distribution, and colonial heritage.

These are the Italian Statistical Office (ISTAT) definitions of generations. ISTAT defines a “generation” as an identifiable group of individuals who share birth years and significant historical events, such as economic changes and major social transformations, during late adolescence and early adulthood (Inglehart, 1997). Exposure to common economic, social, and historical contexts leads individuals in a generation to share similar values, beliefs, and lifestyles, distinguishing them from others (Ting et al., 2017).

See Brugiavini et al. (2014).

The Supplementary Appendix sets out the results with an alternative matching algorithm, Nearest Neighbour Matching.

The results for the probit model for the propensity score and the covariate balancing test have not been included but are available on request from the authors. The model described in Section “Empirical Strategy” enables a balanced estimate of the propensity score. The covariate balancing test shows that the matching is effective in removing differences in observable characteristics between individuals exposed (“treated”) and not exposed (“control”) to ACE. Specifically, the median absolute bias is reduced by roughly 40%-65% depending on the macro region and the matching technique.

We run the model adopting Nearest Neighbour Matching: For the sake of brevity, results are shown in the Supplementary Appendix.

References

Abegunde, D. O., Mathers, C. D., Adam, T., Ortegon, M., & Strong, K. (2007). The burden and costs of chronic diseases in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet, 370(9603), 1929–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61696-1.

Almond, D., Currie, J., & Duque, V. (2018). Childhood circumstances and adult outcomes: act II. Journal of Economic Literature, 56(4), 1360–1446.

Anda, R. F., Croft, J. B., & Felitti, V. J., et al. (1999). Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA, 282, 1652–1658.

Anda, R. F., Whitfield, C. L., Felitti, V. J., Chapman, D., Edwards, V. J., Dube, S. R., & Williamson, D. F. (2002). Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatric Service, 53(8), 1001–9.

Bellis, M. K., Lowey, H., Leckenby, N., Hughes, K., & Harrison, D. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences: retrospective study to determine their impact on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. Journal of Public Health, 36(1), 81–91.

Brugiavini, A., & Weber, G. (2014). Long-term Consequences of the Great Recession on the Lives of Europeans, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1-208 (ISBN 9780198708711).

Caliendo, M. & Kopeining, S. (2008). Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J. Econ. Surv, 22(1), 31–72.

Campbell, F., Conti, G., Heckman, J. J., Moon, S. H., Pinto, R., Pungello, E., & Pan, Y. (2014). Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science, 343(6178), 1478–1485.

Carneiro, P., & Ginja, R. (2016). Partial insurance and investment in children. The Economic Journal, 126(596), 66–95.

Case, A., Fertig, A., & Paxson, C. (2005). The lasting impact of childhood health and circumstance. Journal of Health Economics, 24, 365–389.

Chang, X., Jiang, X., Mkandarwire, T., & Shen, M. (2019). Associations between adverse childhood experiences and health outcomes in adults aged 18–59 years. PLoS One, 14(2), e0211850 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211850.

Coltrane, S. (2004). Elite Careers and Family Commitment: It's (Still) about Gender. The Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci, 596(1), 214–220.

Costa-Font, J., & Gil, J. (2005). Obesity and the incidence of chronic diseases in Spain: a seemingly unrelated probit approach. Economics & Human Biology, 3(2), 188–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2005.05.004.

Cuhna, F., & Heckman, J. J. (2008). Formulating, identifying and estimating the technology of cognitive and noncognitive skill formation. Journal of Human Resources, 43(4), 738–782.

Cuhna, F., Heckman, J. J., & Schennach, S. M. (2010). Estimating the technology of cognitive and noncognitive skill formation. Econometrica, 78(3 May), 883–931.

Devaux M., & Sassi F. (2015). The labour market impacts of obesity, smoking, alcohol use and related chronic diseases. OECD Health Working papers no. 86, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrqcn5fpv0v-en.

Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Edwards, V. J., & Croft, J. B. (2002). Adverse childhood experiences and alcohol abuse as an adult. Addict Behav, 27(5), 713–25.

Elwood, P., Galante, J., Pickering, J., Palmer, S., & Bayer, A., et al. (2013). Healthy lifestyles reduce the incidence of chronic diseases and dementia: evidence from the caerphilly cohort study. PLoS One, 8(12), e81877 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081877.

Feigl, A. B., Goryakin, Y., Devaux, M., Lerouge, A., Vuik, S., & Cecchini, M. (2019). The short-term effect of BMI, alcohol use, and related chronic conditions on labour market outcomes: A time-lag panel analysis utilizing European SHARE dataset. PLoS One, 14(3), e0211940 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211940.

Finkelhor, D., Shattuck, A., Turner, H., & Hamby, S. (2015). A revised inventory of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect, 48, 13–21.

Ford, E. S., Anda, R. F., & Edwards, V. J., et al. (2011). Adverse childhood experiences and smoking status in five states. Preventive Medicine, 53, 188–193.

Francesconi, M., & Heckman, J. J. (2016). Child development and parental investment: introduction. The Economic Journal, 126, 1–27.

Gunstad, J. & Paul, R., et al. (2006). Exposure to early life trauma is associated with adult obesity. Psychiatry Research, 142(1), 31–37.

Hardt, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 260–273.

Hardt, J., Sidor, A., Bracko, M., & Egle, U. T. (2006). Reliability of retrospective assessments of childhood experiences in Germany. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(9), 676–683. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000235789.79491.1b.

Havari, E., & Mazzonna, F. (2015). Can we trust older people’s statements on their childhood circumstances? Evidence from SHARELIFE. European Journal of Population, 31, 233–257.

Ichino, A., Mealli, F., & Nannicini, T. (2008). From temporary help jobs to permanent employment: what can we learn from matching estimators and their sensitivity? J. Appl. Econ., 23, 305–327.

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: cultural economic and political change in 43 societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mensah, Y. M. & Chen, H.-Y. (2013). Global clustering of countries by culture – an extension of the GLOBE study. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2189904 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2189904

Morman, M.T., & Floyd, K. (2002). A “changing culture of fatherhood”: Effects on affectionate communication, closeness, and satisfaction in men's relationship with their fathersand their sons. Western Journal of Communication, 66(4), 395–411.

Di Novi, C., & Marenzi, A. (2009). The smoking epidemic across generations, genders, and educational groups: a matter of diffusion of innovations. Economics and Human Biology, 33, 155–168.

Otang-Mbeng, W., Otunola, G. A., & Afolayan, A. J. (2017). Lifestyle factors and co-morbidities associated with obesity and overweight in Nkonkobe Municipality of the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 36, 22 https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-017-0098-9.

Rosenbaum, P.R. & Rubin, D.B. (1983). The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika, 70, 41–55.

Saracho, O. N., & Spodek, B. (2008). Trends in Early Childhood Mathematics Research. In Saracho, O. N. & Podek B. (Eds.), Contemporary Perspectives in Early Childhood Education (p. 7). Charlotte, NC: Age Publishing Inc.

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2013). The neglect of child neglect: a meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(3), 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0549-y.

Straus, M. A., Kinard, E. M., & Williams, L. M. (1997). The neglect scale, report, family research laboratory. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire.

Sturm, R. (2002). The effect of obesity, smoking, and drinking on medical problems and costs. Health Affairs, 21(2), 33–41.

Sturm, R., & Wells, K. B. (2001). Does obesity contribute as much to morbidity as poverty or smoking? Public Health, 115(3), 229–35. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj/ph/1900764. PMID: 11429721.

Ting, H., de Run, L. T., Koh, E. C. H., & Sahdan, M. (2017). Are we baby boomers, gen X and gen Y? A qualitative inquiry into generation cohorts in Malaysia Kasetsart. J. Soc. Sci., 39(109-), 115.

Yach, D., Hawkes, C., Gould, C. L., & Hofman, K. J. (2004). The global burden of chronic diseases: overcoming impediments to prevention and control. JAMA., 291(21), 2616–22. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.21.2616. PMID: 15173153.

Young, S. Y. N., Hansen, C. J., Gibson, R. L., & Ryan, M. A. K. (2006). Risky alcohol use, age at onset of drinking, and adverse childhood experiences in young men entering the US Marine Corps. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 160, 1207–1214. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.160.12.1207.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi dell'Insubria within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brugiavini, A., Buia, R.E., Kovacic, M. et al. Adverse childhood experiences and unhealthy lifestyles later in life: evidence from SHARE countries. Rev Econ Household 21, 1–18 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09612-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09612-y