Abstract

Foreseeable income reductions around retirement should not affect aggregate consumption. However, given higher leisure endowments after retirement, theory also predicts lower consumption of leisure substitutes. To avoid misinterpreting this predicted drop as a puzzle, our novel approach focuses on housing consumption (complementary to leisure in utility) and controls for leisure changes. In Germany tenants represent roughly half of all households, making many housing expenditures directly observable in micro data. We find significant negative impacts of the retirement status on housing consumption, which is hard to reconcile with life-cycle theory. Despite the lock-in nature of past housing decisions, income reductions at retirement have additional – though small – effects on housing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Do people save too little? Or more precisely, do they undersave compared to the benchmark prediction of the standard life-cycle model pioneered and formalized by Friedman (1957), Modigliani and Brumberg (1954)? Undersaving would mean that people are unable to smooth their consumption paths according to the permanent-income hypothesis of consumption and saving,Footnote 1 and the prime example “of undersaving is probably the observation that, upon retirement, individuals, on average, reduce consumption substantially” (Akerlof, 2002, p. 424). That is the well-known retirement-consumption puzzle. Since the consumption function is a central building block of many economic models, it is a fundamentally important issue whether the standard life-cycle model provides a good approximation to reality or not. By conducting a new test of the consumption-smoothing hypothesis we contribute to the literature on whether the life-cycle theory of consumption is valid in general. The novelty of our approach revolves around our focus on housing consumption and explicitly taking into account the discontinuous increase of available leisure time.Footnote 2 First, these expenditures cannot be substituted by the increased leisure after retirement. Second, we exploit the fact that the majority of the German population do not own their homes, which means (a) that their housing expenditures are directly observable as rents paid, and (b) that they are potentially more prone to the undersaving problem due to the absence of housing wealth.

There is no consensus in the economic literature on the existence of a retirement-consumption puzzle, and the debate is still ongoing. On the one hand, there is the position that “retired people are commonly believed to tailor their consumption to a concept of income rather than to the value of their assets” (Akerlof, 2007, p. 18). A related finding is the tendency of retirees to decumulate their wealth more slowly than expected, see Ventura and Horioka (2020) for the case of Italian retirees.

Banks et al. (1998, p. 769) conclude after analyzing UK micro data: “We argue that the only way to reconcile fully the fall in consumption with the life-cycle hypothesis is with the systematic arrival of unexpected adverse information.” This finding would at least reject the life-cycle-cum-rational-expectations strong form of the model, since “systematic” and “unexpected” together are incompatible with rational expectations. Bernheim et al. (2001) also reject life-cycle models in favor of rule-of-thumb or mental-accounting savings behavior. Benartzi and Thaler (2007) cite broad evidence that the standard model fails.Footnote 3 A recent empirical claim based on the German SOEP micro data was put forward by Grabka et al. (2018), who found that 33% of people entering retirement would have to curtail their consumption expenditure levels.Footnote 4

On the other hand there is an important opposing strand of the literature which argues that extended models of optimizing and forward-looking behavior are compatible with the empirical observations, see also Hurst (2008) for a survey, and Hurd and Rohwedder (2008) for associating changes in consumption with these arguments.

First and perhaps most fundamentally, Aguila et al. (2011) do not find any expenditure drop after retirement at all for non-durable consumption goods, using micro panel data for the US. A very similar result for German expenditure survey data was found by Beznoska and Steiner (2012).Footnote 5 However, we will argue in the theory section below that these broad constancy findings might constitute a puzzle in the opposite direction, implying higher post-retirement utility levels after counting in the increased availability of leisure. Scholz et al. (2006) claim that the household-specific predictions from an optimizing model with a realistic account of the environment are close to observed wealth values; however, still 20% of households hold less wealth than would be prescribed by the optimal decision model.

Second, the increased possibility of substituting market purchases through home production of goods has been addressed repeatedly in the literature. Baxter and Jermann (1999) found that allowing for home production explains the apparent excess sensitivity of consumption to income that seemingly invalidates the permanent-income hypothesis. Aguiar and Hurst (2005) find “dramatically” rising time use on home production which substitutes for example the drop in expenditures on food, such that food consumption stays roughly unchanged for retirees. With German SOEP panel data Schwerdt (2005) finds a positive correlation between consumption reductions at retirement and (proxies for) home production, but he argues that not all of the fall of consumption can be attributed to that effect, because there is a general rise in home production. Lührmann (2010) refined those findings for Germany by combining both consumer expenditures and time use data pre and post retirement. She reveals a significant drop in expenses at retirement which coincides with an increase in time spent on home production. Most recently, Atalay et al. (2020) found a significant increase in time devoted to home production upon retirement using a pension reform in Australia with exogenous variation of the retirement status, which the authors interpret as wellbeing smoothing.

In our view, the aspect of increased home production is just one part of the broader issue of more available leisure time after retirement. Given a non-separable utility function, rising leisure may rationally also lead to other changes in market consumption. In order to circumvent (a) the problem of measuring home production –whether it rises and if so, by enough to substitute the consumption drop– and (b) the utility cross effects on consumption, we focus on housing. Housing costs are a sizeable portion of households’ expenditures (in Germany in recent years up to 2019 around one third, according to the Federal Statistical Office), and they cannot be substituted by home production. Indeed, housing will usually be a complement to the increased leisure time budget in the utility functions of individuals. The German institutional (and possibly cultural) environment is well suited for our analysis because Germany is a country where less than half of all households own their homes. (In our specific subgroup of older men the ownership rate is somewhat higher, at 58%.) This has the advantage that housing expenditures are directly observable for many households as rents paid. For this reason we analyze only non-home owners. Obviously this implies that our results will not be (necessarily) representative for all individuals. Indeed, it is plausible that home owners suffer much less from the under-saving problem precisely because of their owned house or apartment, which represents cumulated savings.Footnote 6 However, since the life-cycle model is a hypothesis relating to all economic agents, focusing on a suitable sub-group is still an informative approach.

We indeed find that (negative) income growth at (foreseeable) retirement helps to explain a reduction of housing consumption in the cross section, after controlling for other factors including leisure changes. The pure retirement status (dummy) always has a strong influence, and while for some operationalizations of the dependent variable this may also capture confounding effects, using the variable in the SOEP questionnaire about housing costs being the reason for moving suggests a causal interpretation. Therefore, our test rejects the life-cycle model of consumption as a generally valid theory of economic behavior. However, the effect is not large even for our subgroup of non-homeowners which may explain the ambiguous conclusions in the existing literature. The leisure change mainly serves as a control variable, but in our given samples it does not have a significant influence on housing consumption, which by itself is not necessarily expected but still compatible with our theoretical framework.

In the next section we make explicit the theoretical background for housing consumption in a stylized life-cycle model that incorporates leisure explicitly. The dataset is introduced and some descriptive evidence is given in Section 3. Section 4 presents and discusses the estimation results and Section 5 concludes.

2 Theory

2.1 A benchmark framework

To fix ideas, let us outline a version of the permanent-income hypothesis that is extended to explicitly include leisure in the utility function in an intratemporally non-separable way. Similar points were made in the past by Heckman (1974) and by Laitner and Silverman (2005), who reversed the argument by maintaining the life-cycle hypothesis and using the observed consumption drop to infer utility parameters. The permanent-income hypothesis is usually formulated in terms of monetary expenditures on goods and services. However, agents really seek to smooth (expected) utility, and the consumption smoothing result relates to consumption in a broad sense, capturing everything that enters the utility function. In our case we have leisure as an additional argument in u(), and thus the life-cycle model of consumption does not necessarily imply that expenditures on consumption goods and services would also be smoothed.

To be explicit we extend the formulation to include two consumption goods that are substitutes and complements to leisure, respectively. And since we do not address issues of risk and volatility we may choose a quadratic but otherwise generic specification with certainty equivalence for any household’s instantaneous utility function u(vt):Footnote 7

where \({v}_{t}=({s}_{t},{k}_{t},{l}_{t})^{\prime}\) is the vector of arguments entering the utility function, the part st + kt represents real expenditures on market consumption goods and lt is the amount of leisure in any period t. For our purposes it is useful to differentiate between two components of the consumption basket according to their utility properties with respect to leisure: st denotes the amount of goods consumed by the household which are (partial) substitutes of leisure, and kt are those goods that are partial complements to leisure. Below we will clarify how housing consumption ht is related to the inputs vt of the utility function.

The term z is a constant and \(a=({a}_{s},{a}_{k},{a}_{l})^{\prime}\) is a coefficient vector, while Q is a symmetric and negative-definite matrix such that u is concave (diminishing marginal returns). A typical element of Q is denoted as qnm, n, m ∈ {s, k, l}.

The vector of marginal utilities is given by

such that the marginal utilities are a + Qvt which are required to be positive (non-satiation). The second-order derivatives are then obtained as

Negative-definiteness of Q in particular implies that all entries on the diagonal must be negative, qss, qkk, qll < 0, and that \({q}_{nn}{q}_{mm}-{q}_{nm}^{2}\,> \,0\). Intuitively, the cross effects qsk, qkl, qsl must not be too large.

Our assumptions about the substitution and complementarity relations between the consumption components and leisure are then formally reflected as follows.

-

qsl < 0: The consumption component st is a (partial) substitute of leisure lt for a typical household.

-

qkl > 0: The component kt is complementary to lt.

-

The sign of the remaining entry qsk reflecting the partial relationship between st and kt is not restricted.

One of the main assumptions in this paper is that the consumption of housing services should be complementary to leisure, because intuitively each euro spent on housing provides more utility if you have more time to spend at your home. According to this hypothesis, housing consumption ht constitutes a part of kt, and the corresponding utility cross effect with respect to leisure would be positive (by qkl > 0).

Notice that overall consumption expenditures may still be (Edgeworth) substitutes with respect to leisure, since the effect of qsl may dominate in the aggregate. We mention this possibility because it is sometimes argued that hours worked, hence non-leisure, are complements of consumption (e.g. Bilbiie, 2020).Footnote 8

For ease of exposition we choose a simple two-period setup, with a pre-retirement period t = 1 and a post-retirement period t = 2. The logic of the analysis goes through in a dynamic setting with a longer life-cycle horizon, because the interesting and non-standard phase is the development before and after the retirement event.

The household seeks to maximize life-time utility

for a given utility discount factor β ∈ [0, 1]. We also consider as given a stylized shift of leisure at retirement with \({l}_{1}=\bar{l}\in [0,1)\) and l2 = 1, such that \({v}_{1}=({s}_{1},{k}_{1},\bar{l})\) and v2 = (s2, k2, 1).

Life-time wealth W is also taken as purely exogenous,Footnote 9 and the budget constraint then reads as: \({s}_{1}+{k}_{1}+\bar{R}{s}_{2}+\bar{R}{k}_{2}=W\). From the corresponding Lagrangian \({\mathcal{L}}=u({v}_{1})+\beta u({v}_{2})+\lambda ({s}_{1}+{k}_{1}+\bar{R}{s}_{2}+\bar{R}{k}_{2}-W)\) we obtain the following optimality FOCs:

In optimum the marginal utilities with respect to the choice variables s, k must be equalized intratemporally, and assuming that time preferences and discount rates roughly coincide (\(1\approx \beta /\bar{R}\)), also intertemporally (Euler equations).

From the determinant of the third leading principal minor of the bordered Hessian matrix for this problem we obtain the (sufficient) condition for a maximum that qsk > (qss + qkk)/2, so the cross effect must be larger than the (negative) mean of the own effects of s and k.Footnote 10

From the purely intratemporal FOCs we get:

Subtracting the second equation from the first one yields:

Next the intertemporal Euler equation for kt results in:

And assuming \(\beta =\bar{R}\) to ease the tractability:

The other Euler equation can be obtained directly or by subtracting (3) from (2) to get:

Using these equations to solve for Δk we get:

The sign of this reaction depends on the numerator qssqkl − qslqsk. We will have Δk > 0 –and thus the shift in leisure will lead to higher housing demand– whenever this numerator is negative. Remembering that qsl < 0 by assumption, the equivalent inequality reads:

Since the right-hand side is positive, we have the following possibilities:

-

qsk = 0: In this special baseline case where the two consumption goods are neutral with respect to each other, condition (6) is obviously fulfilled. For the optimal reactions we get:

$$\begin{array}{lll}{{\Delta }}k=-\frac{{q}_{kl}}{{q}_{kk}}(1-\bar{l}) \, > \, 0\\ {{\Delta }}s=-\frac{{q}_{sl}}{{q}_{ss}}(1-\bar{l})\, < \, 0\end{array}$$ -

qsk < 0: Here again, (6) necessarily holds and thus Δk > 0. Note, however, that by the technical conditions given above the admissible value of qsk is bounded below: \({q}_{sk}> \max \left(({q}_{ss}+{q}_{kk})/2,\ -\sqrt{{q}_{ss}{q}_{kk}}\right)\).

-

qsk > 0: In this case the details of condition (6) are actually relevant and it only holds for values of qsk that are not too large. Again, however, we have the bound \({q}_{sk}<\sqrt{{q}_{ss}{q}_{kk}}\).

2.2 Effects of leisure changes at retirement

Summing up the theoretical exercise, while in general a positive reaction of Δk cannot strictly be proven for any arbitrary utility function, the cases where (6) fails seem quite unlikely. Hence we assume that for plausible parametrizations the sudden increase of leisure at retirement would induce an increase of k (including housing consumption) as an optimal reaction under the assumptions of the life-cycle theory.

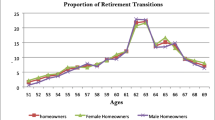

With regard to the part of leisure that is actually connected to the household’s dwelling (home), we cannot observe the time that individuals spend at home in our dataset (see below), but we can use other time-use survey data for Germany to obtain indicative evidence. The latest such survey by the German statistical office was conducted in 2012/2013. In Fig. 1 we have cumulated the time spent on those activities (or non-activities such as sleeping) where it is quite certain that they take place at home. These numbers refer to an average day of the year, and for completeness we also report the gender-specific numbers. This conservative estimate implies that retirees spend on average almost 4 hours per day more at home than individuals doing market work. Furthermore, retirees also travel less than working-age persons: In 2019 the ratio of people having traveled (relative to those who did not) amounted to only 1.6 for the age group 65 and above, compared to 3.7 in the group 55–64 (calculations based on Statistisches Bundesamt (2021)). This supports our assumption of housing expenditures being complementary to the leisure of retirees.

Time spent at home. Left: retirees, right: employed or self-employed. Source: Own calculations based on German time-use survey 2012/2013 (Statistisches Bundesamt (2015), pp. 115–122). “Media usage” comprises reading, watching TV or videos, listening to radio and music; “Household...” sums up kitchen work, home maintenance and improvement, laundry; “Regeneration and private realm” means sleeping, eating, washing, getting dressed etc

As we saw above, the typical case in the life-cycle framework above is that other expenditures decrease, Δs < 0, and this drop in expenditures at retirement could create a positive correlation between current income and some expenditure measures which could be mistaken for the famous retirement-consumption puzzle. Indeed, some analyses of the retirement consumption puzzle have ignored this issue, as a drop in total consumption is not sufficient to falsify the life-cycle theory. The reverse direction is also problematic, however. Contrary to the standard interpretation, empirical demonstrations as in Aguila et al. (2011) that consumption around retirement is constant would actually mean that households react non-optimally and would not be compatible with the life-cycle model, at least under the maintained assumption that leisure is a positive factor of overall utility.

It is important to recognize that the reactions in the life-cycle framework in section 2.1 would happen in response to the rise in leisure, not because of the drop in current income. The reason is the standard assumption of complete financial markets, in particular the absence of liquidity constraints. Therefore, after controlling for the leisure change the expected income change at retirement should not have an effect, as in the traditional formulation of the life-cycle hypothesis without leisure.

2.3 Confounding effects

After presenting our stylized life-cycle framework with leisure and before moving on to the empirical analysis, let us discuss in a less formal way other (fully rational) influences that could play a role for housing consumption changes around retirement.

For example, the search for a new home could be so costly in terms of forgone leisure that it is optimal to postpone it until after retirement, when leisure is not scarce anymore. Contrary to the effect in Section 2.2 this would just be an indirect working of the leisure change, not a direct utility-based influence. However, it would still be controlled for by including a measure of leisure, thus it remains true that the observed income change should not have an effect conditional on these controls. Only the effect of the leisure variable might be confounded. On the other hand, our sample is deliberately restricted to men beyond the age of 55 whose children are typically not very time-demanding of their parents anymore. Note also that the typical amount of hours worked per year is quite a bit lower in Germany than for example in the US. Therefore it seems somewhat implausible that forgone leisure should inhibit people from searching for a cheaper home. Finally, people may hire agents; in Germany those are usually only paid in case of a successful match.

Next, there might be some re(al)location effects around retirement. Workers are geographically bound to some extent by the location of their workplace. They are only free to move away when they retire, and housing might be cheaper for example in rural areas farther away from economic centers. A cheaper home then might not necessarily imply a reduction of the utility value of the home compared to the old one in a more expensive location, such that there would be a mismeasurement. In this case the observed move should then indeed lead to a sufficiently different geographical location, but in our available dataset we cannot fully observe the geographical change. For some households, a related effect could involve increased vacation activities, leading to less time spent at their homes and therefore, less reason to spend money on housing. In any case, to the extent that they exist, such rational reallocation effects should be independent of the income change amount. Instead they would be reflected only in the retirement status dummy, which is included to capture this transaction cost argument. In contrast, the interaction of income change and retirement would not be subject to this effect.Footnote 11

Also, in the case of “early” retirement, the income drop might actually be unexpected, and no consumption smoothing would then be rationally expected. A distinction between anticipated and unanticipated changes is empirically important according to Blau (2008), Haider and Stephens (2007), or Smith (2006). Therefore we control for the early retirement event, but after the 1990s this policy was not used much anymore in Germany. Similarly because of the possibility of confounding effects of unemployment shocks we also experimented with an exclusion of unemployed persons from the sample. However, this restriction did not have noticeable implications and we report only the results where the unemployment status enters as a control.

Finally, it could be argued that there are unanticipated labor supply shocks which would render either the income change at retirement endogenous (assuming that post-retirement work in a different job is possible), or perhaps the timing of retirement. Thus, if such a shock caused somebody to work and earn less, have lower housing expenditures together with higher leisure, this pattern might in some circumstances be confounded with evidence against the PIH. However, ruling out unobservable and systematically biased preference shocks, the remaining candidate for such surprise and permanent shocks would be tax changes. But as Fig. 2 shows, the labor tax rates in Germany have been falling or remained constant in recent years. Therefore there have not been adverse systematic labor supply shocks.

If we depart from fully rational explanations, there are many potentially relevant behavioral economic hypotheses. For example, the existence of norms and/or mental accounting could mean that for an agent her current income is like an entitlement to spend or “norm”-al in the literal sense (Shefrin & Thaler, (1988)). This would imply a dependence of (housing) consumption on current income, after taking into account lock-in effects that would weaken the correlation. Or it could be that agents procrastinate: they might be perfectly aware that they should rationally be moving to a cheaper home, but they do not act accordingly (O’Donoghue & Rabin, (1999)). This explanation in isolation would imply that agents used to have a good reason to live in their expensive home. The most likely case is the space requirement of children. Finally, another simple explanation is myopia, i.e. the assumption that agents simply do not consider their future needs. In its extreme form that would imply that no income changes ever lead to an adjustment of current consumption until wealth is depleted. In general, myopia of course induces undersaving and tends to prevent wealth accumulation.

Note that contrary to widespread conception, the assumption of hyperbolic discounting (present bias) alone is not sufficient to generate an excess sensitivity of consumption to current income, as pointed out for example in Akerlof (2007, fn 39) by invoking the analogy to Barro’s well-known model with bequests Barro (1974): The future selves of an individual in a model with hyperbolic discounting effectively take the role of the heirs in the dynastic model. Also, in a “golden-eggs” model a la Laibson (1997) a rational agent with hyperbolic discounting preferences (and who knows about her time inconsistent preferences) will invest in illiquid assets to avoid temptation in the future. Effectively such an agent makes her future selves liquidity-constrained. A rational agent with hyperbolic discounting would therefore have invested in assets with a corresponding duration (time to maturity).Footnote 12 Thus she would be able to smooth her cash flow and hence her consumption expenditures.

3 Dataset and descriptive evidence

3.1 SOEP

To investigate the housing consumption behavior of people entering retirement we draw on panel data of the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, (2019)). The SOEP is a yearly micro-data panel which has been conducted in annual interviews of individuals and households since 1984 in West Germany and since 1990 in East Germany. It is well suited for our analysis as it contains detailed information on both the retirement and the housing issues. From wave to wave respondents report whether they have changed their employment status because of retirement and whether they have moved to another apartment, including rental costs before and after. Respondents also provide information about their household size, income and other living circumstances. Moreover, this information is available over a long period of time which enables us to gather a decent number of respondents who actually enter retirement within the observation period. One drawback, however, is the fact that household wealth levels are not provided in the SOEP, nor is total consumption available (and by consequence also no current savings).

Despite the many advantages of longitudinal data, panel attrition may be a particular problem when studying moving behavior. According to the official documentation, panel attrition in the SOEP, related to households that were lost after they moved to unknown new addresses, is roughly 0.5% on average each year (Kroh, 2009). If it does have any effect on our results at all, this attrition is expected to bias our findings in the direction of the life-cycle hypothesis.

3.2 Sample selection

Due to some inconsistency in the wording of the SOEP questionnaires before 1993, the retirement event cannot be deduced correctly, so we start with the panel wave 1994 (i.e. t − 1 starts at 1993). We use all available waves, i.e., until 2018. The latest wave including information on reasons for moving refers to 2017, however. Given a massive rent catch-up in East Germany from constrained levels in the years after unification, we leave out East German observations before 1997.

As we want to compare the housing behavior of recently retired workers with other individuals (or households), we do not restrict the sample to those going into retirement. Nevertheless, in order to obtain a relatively homogeneous sample we include men between the ages of 55 and 75, centered around the standard nominal retirement age of 65. The resulting sample size is 9237 respondents with 57,096 observations in total.

An important feature of our analysis is that we focus on home tenants, thus excluding home owners. The main reason for this exclusion is that the current cost of housing is unobservable for non-tenants. But it is clear that home owners tend to stay in their apartments or houses after retirement. In general their behavior is probably consistent with the life-cycle hypothesis to a larger extent than the behavior of tenants, because the asset of a home itself constitutes a considerable savings item for retirement.Footnote 13 Therefore we acknowledge that in our setup we would find non-consumption-smoothing results more easily than in a representative sample of the whole population. If we find violations of the life-cycle hypothesis, this finding might then not apply to the roughly 40% of the households in the SOEP who are home owners. In our subgroup of men aged 55–75 years the fraction is expectedly larger with 57.5%. Hence, the resulting sample of home tenants comprises 3925 observation units with 21,919 observations across the years.

The number of observations along the time dimension is of course different for each cross-sectional unit. Due to the fact that some variables are constructed as first time differences or lags we lose one observation in the time dimension for each unit, leaving us with 17,994 observations. The average number of observed time periods for an included man is 5.5 (median 4), the average pre-retirement number of observations is 2.1, and post-retirement accordingly 3.4.

3.3 Descriptive evidence

First of all, we document the plausible fact that the amount of available leisure increases substantially around retirement. The leisure time use information is gleaned from a set of items in the SOEP questionnaire in which respondents are asked to report the average amount of time per day spent on employment (including travel time to and from work), errands (shopping, errands, citizen’s duties), housework (washing, cooking, cleaning), childcare, other care activities (only since 2001), education or further training, repairs on and around the house, car repairs, garden work, as well as hobbies and other free-time activities. Since we regard leisure time as a rather broad category of one’s disposable time, our leisure variable is calculated as the residual of a day’s 24 h and the individual time uses reported (except education and hobbies). On an annual basis, hours are available for weekdays only (weekends are reported biennially). For this reason, we focus on weekday time use.

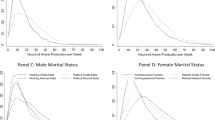

Since a small number of respondents report simultaneous activities totaling more than 24 hours per day, we restrict the sum of all work activities to 18 h per day (thereby requiring at least 6 h of physical rest on average). Employment-related time is taken as reported, and the remaining time uses are scaled down proportionately if they exceed the upper bound. Figure 3 reports the separate distributions of the leisure levels for non-retired and retired men, respectively. The mode of the change distribution appears around 8 h which would correspond to a standard full-time job.

The next fundamental fact consists of the reduction of current income after retirement, displayed in the left-hand entry of Fig. 4. Here it is interesting that the mode occurs just barely below zero. Only few households experience income drops below −35%, which is plausible given the replacement rates prevailing in the German pension system for those cohorts. It is also interesting that a sizable part of the observations displays rising income. As we consider household income, this increase may stem from life insurance contracts that become due or a rising income of the spouse. Hence, it could be the case that there is a different puzzle reflected in those observations, namely the possibility that many people in Germany even have saved too much for old age, given the relatively high level of state-provided old-age pensions and health care benefits, compared to countries like the US. However, that aspect is beyond the scope of this paper.

One advantage of the SOEP data is that it provides rents paid by tenant households that we can use as a direct housing cost measure. Analogously to the leisure and income changes of retirees we report in the right-hand entry of Fig. 4 the distribution of rent growth. The median is negative around −5%, but because of the skewness the mean growth rate is almost zero. Because of the high variance it is not clear from this univariate distribution whether the retirement event determines the location of the housing consumption growth variable.

Apart from the measurement of housing costs in the form of rents, we will also use the following binary variables extracted or constructed from the information in the SOEP in order to analyze the housing consumption decision:

-

\({m}_{i,t}^{co}\) (“move_cost”): Whether respondents answered “for cost reasons” as the main reason for moving. This information is only available in the SOEP from 1997 onwards, and only intermittently after 2013.Footnote 14 Out of all 903 observed moving events, \({m}_{i,t}^{co}=1\) in 143 cases (16%).

-

\({m}_{i,t}^{ch}\) (“move_cheaper”): Whether or not a move to a cheaper home took place. The information about the move event is given in the SOEP. The new home is considered cheaper if Δri,t is negative (the growth rate / log-difference between this year’s and last year’s rent paid). Out of the 999 observed moving events in the applicable sample, 496 lead to a cheaper home (50%)

In Table 1 we compare the incidence of these binary variables in the common sub-sample where both are available. Indeed, in 75% of the lower rent cases (321/429) the respondents do not give priority to the cost argument, while in the majority of moving-for-cost-reason cases (108/141, 77%) they do cut housing expenses. Therefore the two variables are correlated but are not perfect substitutes. The mco variable is especially attractive for our purposes since it provides a self-assessed cause and confounding effects should therefore be less relevant.

4 Specifications and estimates

In all model variants our choice of control variables to account for the background noise of residential mobility is based on and extends the estimation results of Tatsiramos (2006), who studied residential mobility of people over the age of 50 in several European countries using the ECHP. As the German contribution to the ECHP data set is an adjusted sample of the SOEP, we draw on those variables that proved statistically significant in explaining moves in Germany in the specification by Tatsiramos (2006). These include whether the respondent lost his spouse (average 0.4%), experienced a health shock (disability, not the continuing status, 4.0%), lives in a couple (72%) and the overall household size (2.1). In our specification we did not include living in an apartment and whether housing costs are a burden, nor household wealth; for wealth there is no appropriate panel information in the SOEP. In the estimation by Tatsiramos (2006), entering retirement proved an additional important determinant of moving behavior; we will naturally also include a retirement status dummy in our equations, but the dependent variables are different.

While it is in principle unfortunate that we cannot account for wealth variations, this omission renders the measurement of the retirement effect conservative: A positive wealth shock would represent an incentive to retire earlier (as far as possible within the institutional limits), and thereby would introduce some positive correlation component between the retirement status and (housing) consumption. This would entail only a potential upward bias – equivalently a downward bias in the measured impact on the relocation variables mco and mch.

Other control variables are a set of time range dummies, indicators for East (mean of 35%) and North West Germany (referring to the states of Sleswick-Holsatia, Hamburg, Bremen, Lower Saxony, and North Rhine-Westphalia; mean 34%), loss of spouse (0.42%), regular employment status of spouse (24%), German nationality (85%). Furthermore, the size of the home, the real rent, the change of household size as an integer-valued variable, age squared, and the tenure in the current home (divided by 10 as a scaling device) are also controlled for. The three variables in levels – income, rent, and dwelling size – should not be interpreted individually as partial effects, because they could be equivalently recombined for example as rent-income ratio, rent per square meter, and dwelling size. The main income variable capturing a possible puzzle is therefore the change (growth) around retirement. Note that some of the variables are not time-varying and therefore do not appear in fixed-effect specifications below.

4.1 Housing consumption reductions through relocation

The first part of our empirical analysis concerns the events of moving to a cheaper home and/or for cost reasons. In principle all men (between 55 and 75) are included here, irrespective of ever having entered retirement.

For the binary dependent variables as defined before we use the following probability model in our panel context:

where s ∈ {ch, co} indexes the different dependent variables and α are the unobserved individual-specific effects. Note that x contains some time-invariant variables as well as time range dummies. The time dimension for this unbalanced panel varies between all theoretically possible values (1 to 20).

Λ() is the logistic CDF, meaning that we have chosen a (panel) logit model instead of a probit model. For the probit class, a fixed-effects specification that does not suffer from the incidental parameters problem is not available. In contrast, for the panel logit model it is possible to use a conditional likelihood which does not depend anymore on the unit effects and which can be used to estimate the remaining parameters consistently. A random-effects specification requires relatively strong assumptions regarding the unobserved heterogeneity, and as a practical issue we encountered numerical problems with convergence of the random-effects logit estimator algorithm with our data. Using a fixed-effects approach also facilitates the comparison with a recent dynamic specification method as shown below. A standard Hausman test clearly rejects the pooled specifications in favor of (conditional) fixed effects: χ2(10) = 58.9, p = 0.000 for the \({m}_{i,t}^{co}\) equation, and χ2(10) = 115.8, p = 0.000 for the \({m}_{i,t}^{ch}\) equation.

Note that units where all outcomes are the same (all zero or all one over time) do not contribute information to the conditional likelihood for the fixed-effects logit. Hence, below we report sample sizes without those units for the fixed-effects specifications; this is a feature of the conditional fixed-effects model and should not be mistaken for an arbitrary sample selection.

In Table 2 the results of our panel logit estimations with respect to the binary dependent variables of moving to a cheaper home or due to cost reasons are reported. Both variants include time range dummies and further controls as mentioned in the notes. The variables “relative income change” and “relative leisure change” are constructed as interaction effects of the current income (or leisure amount) relative to the pre-retirement level multiplied with the retirement status dummy. They capture the changes occurring at retirement. These variables would be zero throughout for non-retiring households, but the variables are not time-constant in general.

The salient finding is that the retirement status clearly and (statistically) significantly increases the probability of reducing housing consumption by either moving to a cheaper home or moving for (self-reported) cost reasons. As discussed in Section 2.3, in the case of mch (move_cheaper) some confounding effects may be partly responsible for this result. Some survey respondents may also interpret the formulation “moved due to cost reasons” in the questionnaire to simply mean that after retirement they wanted to spend more on other goods and services instead. But for those households who indeed moved because the cost of their dwelling was not affordable anymore, the effect in the mco (move_cost) equation contradicts the life-cycle hypothesis. The higher amount of post-retirement leisure (“relative leisure change”, included with a year’s lag) does not have significant effects on the housing relocation in these specifications.

The income effect is only partly significant in the move_cost equation, which is perhaps surprising. The negative effect of the past year’s overall income level (irrespective of the retirement status) on the propensity to cut housing consumption by moving is expected. But the effects of relative income changes at retirement are not estimated to be significant. This partial result by itself appears consistent with the life-cycle hypothesis.

The coefficients in logit models are not quantitatively meaningful by themselves, and typically the marginal effects would be analyzed. Unfortunately, in a fixed-effect framework this is not directly possible as the level information is lost after purging the individual effects. A quantitative interpretation will be given for the different approach in Section 4.2 below.

The results reported so far were based on a static logit specification, where a dynamic dependency was only allowed indirectly through the variable of the past tenure in the home. Intuitively, however, having moved to a cheaper home (or for cost reasons) in the past year should negatively affect the probability of moving (again) in the current year. This would amount to a dynamic logit specification. The well-known econometric issue with that in a panel context is the incidental parameter problem which leads to biased estimates. A solution is the quasi-logit model (quadratic exponential) proposed by Bartolucci and Nigro (2010), which can be regarded as an approximate dynamic logit model allowing a conditional FE approach. The conditional distribution of the binary dependent variable in the model is given as

where \({e}_{t}^{* }\) is a correction term; in particular, for t < Ti this correction term is approximately \({e}_{t}^{* }\approx 0.5\gamma\) (see Bartolucci and Nigro (2010), p. 724), where Ti is the individual-specific final time period, and thus β1 are (approximately) the only coefficients associated with the covariates \({\bf{x}}^{\prime}\).

We have applied that estimation approach to dynamic versions of the specifications of Table 2, and we report the estimates of γ and β1 in Table 3.Footnote 15 The lagged term appears important only in the move_cheaper equation. In both equations the results remain basically unchanged, therefore the quasi-static logit models do not appear to suffer from omitted dynamic effects.

4.2 Housing consumption pre- vs. post-retirement

As a second empirical approach, we also construct from our panel information a cross-sectional sample where only the men with an observed retirement event are included. One advantage of this specification is that confounding effects regarding the precise timing of retirement are largely avoided, and another one is the straightforward quantitative interpretation of estimated effects. Also, the average number of pre-retirement observations per included man was limited (cf. subsection 3.2), such that it seems useful to complement the previous within-type estimates with a specification that rests on the between information. For those individuals we define two relevant variables to be explained:

-

1.

Rent paid after retirement, relative to pre-retirement levels. (Average real levels over the observed time spans are used, expressed as growth rates from pre- to post-retirement, g(ri), deflated with the consumer price index.)

-

2.

Size of the dwelling after retirement, relative to pre-retirement levels. (Also growth of the average levels, g(si).)

The first variable, growth of rent paid g(ri), directly measures the change of the cost of housing occurring around the retirement event. With the second variable growth of the size g(si) we attempt to control for some of the confounding effects: for example a larger house in a rural area might be cheaper, yet yield higher utility than a small expensive city apartment. However, this relationship is still ambiguous, because a larger apartment in a bad neighborhood might also provide lower utility than a smaller apartment in a good neighborhood.

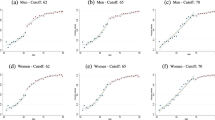

In Table 4 the cross-sectional estimates for these variables are reported. The leisure change relative to pre-retirement levels (second row) does not have a significant impact. In contrast, the income effect at retirement (first row) is precisely estimated. The positive signs of the coefficients mean that a larger income drop at retirement translates into a larger reduction of housing consumption, even after controlling for leisure changes, which contradicts the life-cycle hypothesis as outlined in Section 2.

On the other hand, the magnitude of the effect is certainly limited: For example, a typical drop of income after retirement by 30% would lead to a reduction of the real rent growth by only 4.5 percentage points on average (0.3 × 0.15). Remember that the estimates only refer to non-home owners and as far as they contradict the life-cycle model they are likely to be larger than for home owners.

5 Conclusions

In this paper we have tried to shed new light on the retirement-consumption puzzle. We have argued that predictions of the life-cycle hypothesis must be interpreted conditionally on the large increase of available leisure at retirement, a theoretical insight which is often neglected in the literature. Our analysis is focused on the consumption of housing, based on the assumption that housing enters the utility function as a complement to leisure, and thus under the life-cycle hypothesis it should typically be reduced less than other consumption goods at retirement.

Based on the behavior of 55 to 75-year old men in the German SOEP we first found that (foreseeable) retirement events have a significant effect on moving to cheaper homes and/or moving for cost reasons in a panel econometric analysis. While the decision to move to a cheaper home may be subject to confounding effects, self-reported cost reasons for moving suggest a more causal interpretation. We then also found for the cross-section of retirees that the income drop at retirement has a (negative) effect on housing consumption as measured by rent growth and dwelling size growth. As suggested by our theoretical framework, we controlled for the amount and change of available leisure time which did not turn out to be statistically significant, however.

These findings imply that the smoothing hypothesis of the life-cycle model of consumption and saving may be violated on average for the large subgroup of non-home owners in Germany. In principle our evidence confirms the existence of a retirement-consumption puzzle, contrary to some recent statements in the literature. As the leading explanations of this puzzle are given by behavioral economic theories, aggregate models would have to allow for heterogeneous agents not only in the sense of different endowments and shocks, but also in the sense of different behavioral rules in order to capture these aspects of reality.

However, some qualifications of our results should be noted. First, our sample was deliberately restricted to non-homeowners, and we expect the life-cycle model to be more accurate for home owners due to their systematically higher cumulated savings that financed their home in the first place. Secondly, in some specifications we did not find effects of current income after retirement. Thirdly, the elasticity with respect to housing expenditure growth appears to be quite small. Finally, and on a more general note, our interpretation builds on the notion of stable individual preferences and would not hold in case of a systematic, but unanticipated preference shock at retirement. This, however, would be an even greater violation of the life-cycle hypothesis than the one we are deriving. In our view, whether the life-cycle model is still justified as an approximation depends on the characteristics of the concrete application for which the model is going to be used.

Notes

Of course consumption smoothing may still imply rising or falling consumption paths given differentials between personal time discount rates and net (after-tax) interest rates, but discrete and sudden jumps are ruled out.

The influence of leisure hours (a mirror image of hours worked, the labor market status) on consumption can be traced back at least to Heckman (1974). Some parts of that insight seem to have been lost over the years and are not always found in the recent literature, however.

They ignore the usual drop of work-related expenses after retirement but argue that on the other hand increasing expenditures for health care consumption at old age are also neglected in the literature.

In their estimates (as opposed to the descriptive sample-split evidence) they even get a positive effect of the pure retirement dummy.

Also, the income of home owners in our specific subgroup is almost 50% higher than that of tenants. Intuitively this makes undersaving less likely for the former, although consumption smoothing can also be violated at higher levels of income.

Here we do not analyze the intra-household allocation or decision problem explicitly. See Lundberg et al. (2003) for the scope of bargaining models in this context or Stancanelli and Van Soest (2012) for spouses’ joint retirement decisions. For simplicity we also ignore a non-deterministic end of the life cycle. Finally, we could in principle treat all parameters as household-specific with an additional index i, but in the empirical part we make the standard assumption of homogeneous coefficients except for household-specific fixed effects. Therefore we abstract from individual heterogeneity here for notational simplicity.

Marginal utility of composite consumption s + k depends on the consumption shares according to which an extra euro is divided. Let the share of substitutive goods be ϕs = s/(s + k). Then approximately uc ≡ ∂u/∂(s + k) = ϕsus + (1 − ϕs)uk. The cross effect with leisure is then given as ucl = ϕsqsl + (1 − ϕs)qkl, which Bilbiie argues to be negative. This condition is equivalent to ϕs/(ϕs − 1) < qkl/qsl(<0). Suppose housing expenditures were the only component of k, then a plausible value for the share might be ϕs = 70%, which would yield the condition − 2.33 < qkl/qsl. Such a constellation would be perfectly compatible with our assumptions, see condition (6) below and the discussion following it.

It might be spelled out as \(W=(1-\bar{l})\bar{w}+\bar{R}\bar{p}(1-\bar{l})\bar{w},\) where for a given wage rate \(\bar{w}\) the first part is labor income, and the second part is a discounted pension income, where \(\bar{p}\) is a fixed replacement ratio relative to labor income and \(\bar{R}\) is a financial discount factor. However, given the exogeneity assumption in this framework which focuses on the demand side, the details are obviously not important.

This complements the condition from the utility function that since \({q}_{ss}{q}_{kk}-{q}_{sk}^{2}\, > \, 0\) must hold by concavity, the cross effect between st and kt must be less than the geometric average of the respective own effects: \(| {q}_{sk}| <\sqrt{{q}_{ss}{q}_{kk}}\).

The 5 × 5 bordered Hessian here can be reported in its symmetric-stacked form: \(vech(H)=(0,1,1,\bar{R},\bar{R},\ {q}_{ss},{q}_{sk},0,0,\ {q}_{kk},0,0,\ \beta {q}_{ss},\beta {q}_{sk},\ \beta {q}_{kk})^{\prime}\). Actually, from the determinant of the fourth leading principal minor we obtain a refined condition for these relationships: \(2{q}_{sk}-({q}_{ss}+{q}_{kk})\ -\ \bar{R}({q}_{ss}{q}_{kk}-{q}_{sk}^{2})\, > \, 0\), so \(2{q}_{sk}-({q}_{ss}+{q}_{kk})\, >\, \bar{R}({q}_{ss}{q}_{kk}-{q}_{sk}^{2})\, > \, 0\).

In the empirical specifications in Section 4 this income change around retirement appears in two incarnations: In Section 4.1 based on panel econometric methods it is an explicit interaction effect of the income difference and the retirement status, whereas in Section 4.2 in a cross-sectional approach it is the income change variable itself, given that the construction of the sample and the data already imply the retirement event.

In developed countries such as Germany those types of assets clearly exist and are quite widespread; for example so-called “capital life insurance” contracts which are essentially savings plans that pay an annuity or a lump-sum payment after retirement.

A mirror image of these savings is that housing costs tend to be higher for tenants (Lozano Alcántara & Romeu Gordo, 2020).

Namely it is absent in 2014, 2016, 2018. This structure with gaps obviously means that that part of the sample is not usable for dynamic specifications.

We have used the DPB package for gretl to achieve this, see Lucchetti and Pigini (2017).

References

Aguiar, M., & Hurst, E. (2005). Consumption versus expenditure. In: Journal of Political Economy 113.5, pp. 919-948. http://ideas.repec.org/a/ucp/jpolec/v113y2005i5p919-948.html.

Aguila, E., Attanasio, O., & Meghir, C. (2011). Changes in consumption at retirement: evidence from panel data. In: Review of Economics and Statistics 93.3, pp. 1094–1099.

Akerlof, G. A. (2002). Behavioral macroeconomics and macroeconomic behavior. In: American Economic Review 92.3, pp. 411–433. http://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/aecrev/v92y2002i3p411-433.html.

Akerlof, G. A. (2007). The missing motivation in macroeconomics. In: American Economic Review 97.1, pp. 5–36. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.1.5.

Atalay, K., Barrett, G. F., & Staneva, A. (2020). The effect of retirement on home production: evidence from Australia. In: Review of the Economics of the Household 18, pp. 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-019-09444-3.

Attanasio, O. P., & Browning, M. (1995). Consumption over the life cycle and over the business cycle. In: American Economic Review 85.5, pp. 1118–37. http://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/aecrev/v85y1995i5p1118-37.html.

Banks, J., Blundell, R., & Tanner, S. (1998). Is there a retirement-savings puzzle? In: American Economic Review 88.4, pp. 769–88.

Barro, R. J. (1974). Are government bonds netwealth? In: Journal of Political Economy vol 82, no 6, pp. 1095–1117.

Bartolucci, F., & Nigro, V. (2010). A dynamic model for binary panel data with unobserved heterogeneity admitting a root-n-consistent conditional estimator. In: Econometrica 78.2, pp. 719–733.

Baxter, M., & Jermann, U. J. (1999). Household production and the excess sensitivity of consumption to current income. In: American Economic Review 89.4, pp. 902–920. http//ideas.repec.org/a/aea/aecrev/v89y1999i4p902-920.html.

Benartzi, S., & Thaler, R. H. (2007). Heuristics and biases in retirement savings behavior. In: Journal of Economic Perspectives 21.3, pp. 81–104.

Bernheim, B. D., Skinner, J., & Weinberg, S. (2001). What accounts for the variation in retirement wealth among U.S. households? In: American Economic Review 91.4, pp. 832–57.

Beznoska, M., & Steiner, V. (2012). Does Consumption Decline at Retirement? Evidence from Repeated Cross-Section Data for Germany. Discussion Paper 14. Free University of Berlin School of Business & Economics.

Bilbiie, F. O. (2020). A GHH-CRRA Utility for Macro: Complementarity, Income, and Substitution.

Blau, D. M. (2008). Retirement and consumption in a life cycle model. In: Journal of Labor Economics 26, pp. 35–71. http://ideas.repec.org/a/ucp/jlabec/v26y2008p35-71.html.

Campbell, J. Y., & Mankiw, N. G. (1990). Permanent income, current income, and consumption. In: Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 8.3, pp. 265–79. http://ideas.repec.org/a/bes/jnlbes/v8y1990i3p265-79.html.

Friedman, M. (1957). A Theory of the Consumption Function. Princeton U Press.

Grabka, M. M., Bönke, T., Göbler, K., & Tiefensee, A. (2018). Rentennahe Jahrgänge haben große Lücke in der Sicherung des Lebensstandards. In: DIW Wochenbericht 37. https://doi.org/10.18723/diw_wb:2018-37-3.

Haider, S. J., & Stephens, M. (2007). Is there a retirement-consumption puzzle? Evidence using subjective retirement expectations. In: The Review of Economics and Statistics 89.2, pp. 247–264. http://ideas.repec.org/a/tpr/restat/v89y2007i2p247-264.html.

Heckman, J. J. (1974). Life cycle consumption and labor supply: an explanation of the relationship between income and consumption over the life cycle. In: American Economic Review 64.1, pp. 188–194. https://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/aecrev/v64y1974i1p188-94.html.

Hurd, M. D., & Rohwedder, S. (2008). The retirement consumption puzzle: actual spending change in panel data. NBERWorking Papers 13929. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. http://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/13929.html.

Hurst, E. (2008). The retirement of a consumption puzzle. NBER Working Papers 13789. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. http://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/13789.html.

Kroh, M. (2009). Documentation of sample sizes and panel attrition in the German socio economic panel (SOEP) (1984 until 2008). Data Documentation 47. DIW.

Laibson, D. (1997). Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. In: The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112.2, pp. 443–77. http://ideas.repec.org/a/tpr/qjecon/v112y1997i2p443-77.html.

Laitner, J., & Silverman, D. (2005). Estimating life-cycle parameters from consumption behavior at retirement. Working Paper 11163. NBER. https://doi.org/10.3386/w11163.

Lozano Alcántara, A., & Romeu Gordo, L. (2020). Measuring housing costs and housing affordability using SOEP: An Example Applied to Older Households. Tech. rep. 1111. SOEPpapers. 30 pp. https://www.diw.de/de/diw_01.c.803525.de/publikationen/soeppapers/2020_1111/measuring_housing_costs_and_housing_affordability_using_soep__an_example_applied_to_older_households.html.

Lucchetti, R., & Pigini, C. (2017). DPB : Dynamic Panel Binary Data Models in gretl. In: Journal of Statistical Software 79.8. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v079.i08.

Lührmann, M. (2010). Consumer expenditures and home production at retirement: new evidence from Germany. In: German Economic Review 11, pp. 225–245.

Lundberg, S., R. Startz, & S. Stillman (2003). The retirement-consumption puzzle: a marital bargaining approach. In: Journal of Public Economics 87.5–6, pp. 1199–1218.

Modigliani, F., & Brumberg, R. H. (1954). Utility analysis and the consumption function: an interpretation of cross-section data. In: Post-Keynesian Economics. Ed. by Kenneth K. Kurihara. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, pp. 388–436.

O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (1999). Procrastination in preparing for retirement. In: Behavioral Dimensions of Retirement Economics. Ed. by H.J. Aaron. Brookings Institution Press. Chap. 4, pp. 125–56.

Reis, R. (2006). Inattentive consumers. In: Journal of Monetary Economics 53.8, pp. 1761–1800. http://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/moneco/v53y2006i8p1761-1800.html.

Scholz, J. K., Seshadri, A., & Khitatrakun, S. (2006). Are Americans Saving “Optimally” for Retirement? In: Journal of Political Economy 114.4, pp. 607–643. http://ideas.repec.org/a/ucp/jpolec/v114y2006i4p607-643.html.

Schwerdt, G. (2005). Why Does Consumption Fall at Retirement? Evidence from Germany. In: Economics Letters 89.3, pp. 300–305.

Shefrin, H. M., & Thaler, R. H. (1988). The Behavioral Life-Cycle Hypothesis. In: Economic Inquiry 26.4, pp. 609–43.

Smith, S. (2006). The Retirement-Consumption Puzzle and Involuntary Early Retirement: Evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. In: Economic Journal 116.510, pp. C130–C148. http://ideas.repec.org/a/ecj/econjl/v116y2006i510pc130-c148.html.

SOEP (2019). Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), data from 1984–2018. https://doi.org/10.5684/soep-core.v35. http://www.diw.de/soep.

Stancanelli, E., & Van Soest, A. (2012). Retirement and Home Production: A Regression Discontinuity Approach. In: American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 102.3, pp. 600–605.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2015). Zeitverwendungserhebung 2012/2013. Aktivitäten in Stunden und Minuten für ausgewählte Personengruppen. Tabellenband zur Zeitverwendungserhebung 2012/2013.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2021). Statistik über die touristische Nachfrage—Reiseverhalten. https://wwwgenesis.destatis.de/genesis/online?sequenz=tabellen&selectionname=45413 (visited on 05/02/2021).

Tatsiramos, K. (2006). Residential Mobility and Housing Adjustment of Older Households in Europe. IZA DP 2435. Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit/Institute for the Study of Labor.

Ventura, L., & Horioka, C. Y. (2020). The wealth decumulation behavior of the retired elderly in Italy: the importance of bequest motives. In: Review of Economics of the Household. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09486-y.

Acknowledgements

We thank Aunt Ingrid for (unknowingly) inspiring this paper. We also thank anonymous referees as well as seminar participants at the IMK, Free University Berlin, MEA SAVE conference, the Econometric Society World Congress, University Magdeburg, University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, European Economic Association and Verein für Socialpolitik meetings for helpful comments and Christopher Gardiner for research assistance.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Institutional information Germany

It may be useful to summarize some characteristics related to the German housing market.

There is a means-tested subsidy called “housing money”: Wohngeld. For registered unemployed it was subsumed under general unemployment benefits and social assistance (ALG II) starting in 2005 with the Hartz reform. Those who receive Wohngeld are already in an “appropriate” apartment, so they should not have any reason to move to a cheaper home. In any case, the subsidy is part of the measured household income.

The time that must elapse after the tenant announces his desire to end a rent contract until the contract legally ends had been subject to another reform: since June 2005 it is generally only 3 months for tenants, whereas until August 2001 it was up to 12 months dependent on the past contract duration. Between September 2001 and May 2005 it depended on whether it was an old contract (old rules) or new contract (new rules). In contrast, for landlords it has always depended on the contract duration and mirrors the old rules for tenants (up to 12 months).

Here is a summary of historical regulations of rent increases applying to apartments which are not “price constrained” (without Mietpreisbindung –note that there are also apartments where construction was state-subsidized and rents are therefore price constrained).

-

Within 3 years the rent in an existing contract can only grow by 20% not counting recurrent costs like staircase cleaning or elevator maintenance etc. (Betriebskosten), or modernization expenses.

-

The increased rent may not exceed (by too large a margin) the “local standard comparison rent” (LSCR, ortsübliche Vergleichsmiete) which is determined based on official surveys.

-

Raising the rent requires mandated approval by the tenant; if the tenant does not grant this, the landlord must sue the tenant to legally get the mandated approval, and prove in court that the rent increase meets legal requirements (e.g. conforms to LSCR).

-

A contract with a new tenant may not specify a rent exceeding the LSCR by roughly 50%, but within this limit the landlady is in principle free to choose which amount she demands. These limits were generally narrowed by a recent reform (2015).

Further information on the variables

2.1 The retirement event

The fraction of observations with a retirement event is 3.4%, where the construction of the retirement event dummy is actually not trivial: In the SOEP questionnaire, respondents who have entered retirement recently (since last year’s survey) can be identified with a combination of questions (i) on the termination of the last job within the past or the current year and (ii) on the reason for leaving that job. This information is available and, to the best of our knowledge, reliable since the survey year 1993. We define the variable “entering retirement” as taking the value 1 if the respondent reports the termination of his job since last year’s questionnaire and old-age pension or early retirement as the reason for this event. Entering an early-retirement scheme is also considered in an additional variable “early retirement” which, correspondingly, takes the value 1 if the respondent reports the termination of his job since last year’s questionnaire and early retirement as the reason for this event. We interpret “early retirement” as an interaction variable which covers the additional effect of entering retirement rather unforeseeably and therefore unanticipatedly. In the SOEP questionnaire, the early retirement information is available until the year 1998 only. Hence the variable is always zero afterwards. However, if a respondent reports a (regular) retirement event in two subsequent years, we interpret the first event as an early retirement and set the respective variable to 1.

2.2 Distributions of control variables

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beblo, M., Schreiber, S. Leisure and housing consumption after retirement: new evidence on the life-cycle hypothesis. Rev Econ Household 20, 305–330 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-021-09569-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-021-09569-4