Abstract

Using data from the World Health Organization’s Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE), we evaluate the relationship between gender and several measures of subjective well-being among older adults in developing countries. Furthermore, we contrast the partial associations of gender with these well-being measures when controlling only for age (age-adjusted analyses) with the corresponding partial associations when including individual characteristics and life circumstances as controls (multivariable-adjusted analyses). While age-adjusted analyses reveal that older women have lower levels of evaluative well-being than older men, multivariable-adjusted analyses show that - given similar life circumstances - they have equal or slightly higher evaluative well-being. This suggests that the gender gap in evaluative well-being may be explained by less favorable life circumstances of older women. Age-adjusted results also show that older women tend to have lower levels of emotional well-being. However, we find no reversal, but merely an attenuation of these gender differences in emotional well-being when controlling for additional individual characteristics and life circumstances. Finally, we perform Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions to disaggregate the gender gaps in well-being into explained parts - attributable to gender differences in individual characteristics and life circumstances - and unexplained parts - related to gender differences in the association between life circumstances and subjective well-being. These results further corroborate our findings that women tend to be disadvantaged in terms of both evaluative and emotional well-being, and that this disadvantage is mostly driven by observable factors related to the explained part of the decomposition, such as gender differences in socio-economic status and health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In spite of encouraging trends towards the reduction of gender inequalities in many aspects of life during the last decades (Stotsky et al. 2016), women continue to face circumstances that often inequitably affect their well-being. For example, data collected between 2000 and 2016 in about 90 countries indicate that women spend roughly three times as many hours in unpaid domestic and care work as men (United Nations Publication 2018), which may contribute to gender differences in subjective well-being in favor of men (Flores et al. 2020). Moreover, women tend to be overrepresented among the poor (Quisumbing et al. 2001; OECD 2013) and often control a lower share of households’ resources (Grabka et al. 2015), while also being less likely to influence their household’s financial and other important family decisions (Bernasek and Bajtelsmit 2002; Luhrmann and Maurer 2008). Corresponding life-long gender differences in wealth accumulation may thereby impact the well-being of older women in particular by hindering their financial security (Grabka et al. 2015). Finally, although women generally outlive men, women nonetheless often have higher prevalence of functional health limitations than men (Verbrugge 1985; Denton et al. 2004). In view of the above differences, and according to the double jeopardy hypothesis, older women may be particularly vulnerable. Indeed, being both old and female, older women belong to a population group that may be subject to the “combined negative effects of occupying two stigmatized statuses”, which can be “greater than occupying either status alone” (Chappell and Havens 1980, p. 157). Moreover, living in poorer countries may further exacerbate this vulnerability relative to corresponding old-age gender differences in high-income countries (Jayachandran 2015).

However, old age may not always result in lower levels of subjective well-being, as suggested by several theories such as the socio-emotional selectivity theory (Carstensen 1995; Carstensen et al. 1999), the emotional maturity theory (Kato et al. 1996; Ticehurst et al. 1996), or the selective optimization with compensation theory (Baltes and Baltes 1990) as well as corresponding empirical work on this topic (Blanchflower and Oswald 2008; Stone et al. 2010; Carstensen et al. 2011; Dolan et al. 2017; Kieny et al. 2020). By contrast with the double jeopardy hypothesis, the age as leveler hypothesis argues that gender inequalities may be decreasing in old age, as all individuals suffer from the physical effects of age (Markides and Black 1996). In addition, as argued by Knodel and Ofstedal (2003), older men may be disadvantaged as compared to older women in some spheres. From a life course perspective, for example, women may benefit from greater role continuity as care-givers, while men may suffer from role disruption and loss of social status after retirement, which can lead to reduced self-esteem and loss of social support. Moreover, older mothers may benefit from greater emotional loyalty from their adult children than older fathers (Knodel and Ofstedal 2003).

Against this background, our study aims at investigating and interpreting gender differences in subjective well-being among older adults from several low- and middle-income countries. Subjective well-being is a multifaceted concept comprising at least two key dimensions: evaluative and emotional well-beingFootnote 1. Quantitative analyses of evaluative well-being are more common in the well-being literature in economics and intend to capture the cognitive evaluation that individuals have of their own life. Assessments of emotional well-being, by contrast, quantify and contrast the positive and negative affective experiences of individuals such as feeling calm, relaxed, worried, or angry. Positive and negative affects may also be combined into an overall affect balance score, capturing so-called “net affect”. Measures of evaluative well-being may be more influenced by memory, individual reporting biases, cultural disposition and self-conceptualization than measures of emotional well-being (Kahneman and Krueger 2006; Kahneman and Riis 2005). Beyond capturing complementary aspects of subjective well-being, evaluative and emotional well-being differ with respect to their antecedents and consequences (Kahneman and Riis 2005), and thus often show different associations with individual life circumstances such as employment status (Knabe et al. 2010) or income (Kahneman and Deaton 2010).

We use data from the World Health Organization’s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE), to compare gender differences in evaluative and emotional well-being in five low- and middle- income countries. In the first part of our analysis, we compare the partial association between subjective well-being and gender when adjusting only for age (“age-adjusted models” hereafter) with the corresponding partial association in models that incorporate a large set of additional covariates (“multivariable-adjusted models” hereafter). The use of control variables in well-being research is subject to a methodological debate. Supporters of an approach using few or no control variables (Glenn 2009) argue that the “total effects” (i.e., the sum of direct and any indirect effects through other variables) obtained through uncontrolled regressions are most relevant for informing policy decisions, especially if some adjusters represent so-called “bad controls” (Angrist and Pischke 2009). By contrast, advocates of approaches based on more extensive multivariable adjustments claim that understanding of the relationship between age and well-being cannot be achieved through focusing solely on bivariate relationships (Blanchflower and Oswald 2008; Blanchflower and Oswald 2009). We use both approaches in our study: The age-adjusted models allow us to examine gender differences in subjective well-being keeping only age fixed, which is more akin in spirit to simple population group comparisons, while the multivariable-adjusted models allow us to estimate the partial association between gender and well-being ceteris paribus. Contrasting the estimates from these models allows us to further investigate the potential role of individual characteristics and life circumstances on the two dimensions of subjective well-being and corresponding gender differences, even if we cannot identify any causal effects in our cross-sectional study design.

Differences in subjective well-being between men and women may be due to corresponding gender differences in the occurrence of observable characteristics (i.e., one gender having different characteristics or life circumstances, such as health, education, and income levels in addition to gender), but could also be due to the way men and women respond to these individual characteristics and life circumstances, e.g., through gender differences in resilience in the face of adversity. Indeed, there is evidence from the psychological literature that men and women show marked differences in their perceptions of and reaction to similar circumstances (Hyde 2007). Therefore, in the second part of our analysis, we use Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions to explore how much of the happiness gap can be attributable to the different observable conditions of men and women as compared to the different ways in which men and women react to the same objective conditions.

Our findings show that women report lower levels of both evaluative and emotional well-being than men of the same age. However - when life circumstances and individual characteristics are controlled for - we find that the gender gap in subjective well-being diminishes drastically, suggesting that differences cannot be attributed solely to an intrinsic gender effect.

2 Data and measures

We use individual- and household-level data from respondents aged 50 and over living in five low- and middle-income countries (China, India, Ghana, Russia and South Africa), which were collected as part of the first wave (2007–2010) of the World Health Organization’s Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE)Footnote 2. SAGE’s database contains comprehensive information on respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, social environment, health and healthcare use, as well as subjective well-being and quality of life. The well-being section includes information regarding both evaluative and emotional well-being. In particular, SAGE contains an abbreviated version of the Day Reconstruction Method (DRM) (Kahneman et al. 2004), which can be used to construct a measure of experienced well-being. A validation study by Miret et al. (2012) shows that SAGE’s abbreviated version of the DRM yields similar data to the administration of a full DRM and therefore delivers a reliable measure of experienced well-being.

We compare evaluative and emotional measures of subjective well-being using four different variables: Life Satisfaction and the WHO Quality of Life Index to measure evaluative well-being, and Emotion Score and Experienced Well-Being to assess emotional well-being.

2.1 Life Satisfaction

Life Satisfaction is measured using a scale from 1 to 5 based on respondents’ answer to the question “Taking all things together, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?”, where 1 corresponds to very dissatisfied and 5 to very satisfied.

2.2 WHO Quality of Life Index (WHOQoL-8 index)

The WHO Quality of Life Index is a composite measure of satisfaction encompassing eight areas: general quality of life, health, energy for everyday life, ability to perform activities of daily living, self-esteem, personal relationships, financial situation, and living conditions. Respondents report their level of satisfaction in each area on a scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). The WHOQoL-8 index (also referred to as EUROHIS-QOL 8 index) is then constructed by aggregating answers from all domains (Power 2003).

2.3 Emotion Score

The Emotion Score quantifies respondents’ affective experiences over the previous day. Individuals report whether they experienced certain emotions during the previous day, disaggregated between 11 negative (feeling worried, rushed, irritated, depressed, tense/stressed, lone/bored, physical pain, sleepiness, stomach ache, headache) and three positive emotions (feeling calm, feeling relaxed, and smiling or laughing a lot). We construct the Emotion Score as the sum of positive minus negative experiences.

2.4 Experienced Well-Being

Experienced Well-Being is a duration-weighted measure of emotional experiences as people go about their everyday lives. We combine time use and activity-specific affect information provided by the abbreviated DRM module of the SAGE data. Respondents report ten successive activities from a list of 22 potential activity types, which they performed during a predetermined period of the day preceding the interview. Respondents indicate how much time they spent in each activity and the prevalence and intensity of two positive (feeling calm or relaxed, and feeling enjoyment), and five negative emotions (feeling worried, rushed, irritated or angry, depressed, tense or stressed). The intensity of each emotion is measured on a three-point scale and aggregated into a measure of “net affect” (Kahneman and Krueger 2006). Due to the large number of potential activity types, some of the 22 activities are reported with low frequencies. Following previous research (Flores et al. 2020; Flores et al. 2020; Kieny et al. 2020), we thus reclassify the 22 activities into five broader activity groupsFootnote 3 - work, housework, travel, leisure, and self-care - to facilitate statistical estimation.

Following Kahneman and Krueger (2006), we define respondent i′s net affect during activity group a, ui,a, as:

Where \(PA_{is}^l\) is the l’th positive affect and \(NA_{is}^k\) is the k’th negative affect recounted by respondent i for each spell s of possibly multiple reports of activity group a. We take the time-weighted average of positive and negative affect scores in order to control for multiple incidences of the same activity group. The net affect of activity a, ui,a, is the weighted sum of net affects over all the occurrences of activity group a in the previous day, where the weight his is the proportion of time spent on each spell s during which activity group a was reported, compared to the total time spent in this activity group. By simply summing positive and negative affects, we assume that net affects are cardinal and that the utility function is time-separable.

We then define Experienced Well-Being as the duration weighted sum of net affects by activity group:

Where \({\uptau}_{{\mathrm{ia}}} = \frac{{T_{ia}}}{{T_i}}\) represents the share of non-sleeping time Tia spent on activity group a by individual i, relative to the total time covered by the 10 successive activity groups reported, Ti, and ui,a represents respondent i’s net affect during activity group a.

2.5 Explanatory variables

While the age-adjusted regressions control only for age besides gender, the multivariable-adjusted regressions control for a considerably larger set of respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics and measures of economic status, namely age, household permanent income quartilesFootnote 4, marital status, number of adults and children living in the household, urban or rural residence, education level and employment status. These models also incorporate measures of respondents’ health status by including the WHO disability index (includes information regarding cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along, life activities, and participation), and self-assessed pain (measures the degree of pain and discomfort experienced in the last month, and whether it caused difficulties in everyday life). Finally, these multivariable-adjusted regressions also include measures of social cohesion such as community involvement (participation in social activities), trust in different groups (neighbors, co-workers or strangers), feeling of safety in the neighborhood and suffering of a violent crime in the last 12 months. It is of note that some factors which are known to affect well‐being and may vary by gender and age are not controlled for. Among others, we are not able to control for the share of joint resources controlled by the woman in couples and familiesFootnote 5, the ability to make one’s own decisions within the household, how one’s situation compares to others’ in the community, or the recent deaths of loved ones.

3 Econometric models

3.1 Partial associations

Evidence shows that well-being measures depend strongly on cultural background (Diener et al. 2003). We, therefore, estimate regressions first on the full sample including country-specific binary variables to control for country differences in intercepts (called pooled models) (Eqs. (3a) and (4a) below) before moving to country-specific estimations on each country’s subsample (Eqs. (3b) and (4b) below). The multi-country setting of our data provides a valuable way of checking the robustness of our findings across countries. In addition, all our measures of subjective well-being are standardized at the country level, which allows us to interpret coefficients in terms of multiples of standard-deviation units within the country-specific distributions of the subjective well-being measure under consideration.

We begin our analysis by evaluating whether there is a gender gap in subjective well-being when controlling only for age. We regress each measure of subjective well-being on our Female variable and ten-year age dummies (as well as country dummies in the case of estimation on the pooled sample). Specifically, we estimate the following models on the pooled sample (3a) and the country-specific samples (3b), respectively:

We then evaluate how the partial association of gender with each measure of subjective well-being changes when controlling for additional personal characteristics and measures of individual life circumstances. Hence, we estimate multivariable-adjusted gender gaps in subjective well-being by performing the same regressions while controlling for a larger set of explanatory variables Xi into our models. Xi, thereby, includes ten-year age dummies as well as explanatory variables related respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics, economic status, health, and social cohesion (as described in the previous section).

To ensure the accurate estimation of the corresponding conditional means of subjective well-being for obtaining mean differences in subjective well-being across population groups (Solon et al. 2013), we estimate these regressions by OLS using sample weights.

3.2 Decomposition Analyses

In the second part of our analysis, we explore to what extent differences in objective life circumstances explain differences in subjective well-being between women and men. We use a decomposition analysis based on Neumark (1988) and inspired by that used by Case and Paxson (2005) to analyze sex differences in morbidity and mortality. This decomposition allows us to assess the role of gender-specific differences in the prevalence of participant’s observable characteristics in the unconditional gender differences in subjective well-being. The decomposition is based on estimating separate linear models for the whole population and for each gender:

where the vectors of β parameters include intercepts and zi refers to the vector of explanatory variables. zi includes 10-year age dummies, as well as covariates related to respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics, economic status, health, and social cohesion (the full list of explanatory variables is described in the data section above). In addition, in pooled sample regressions, zi includes country dummies.

Following Neumark (1988), the unconditional mean gender difference in subjective well-being can be expressed as follows:

where βAll is the vector of coefficients from the full-sample model, and \(\overline z ^{Men}\) and \(\overline z ^{Women}\) are vectors of explanatory variables evaluated at the means for men and women, respectively.

The explained part represents the part of the unconditional difference in subjective well-being that is due to differences in endowments, i.e., individual characteristics and life circumstances, between the two genders. It measures the contribution of differences in the prevalence of different factors in Z between men and women. The unexplained part represents the part of the unconditional difference in subjective well-being that is related to differences in coefficients. This part of the decomposition amounts to differences in the way men and women react to or evaluate their objective circumstances as indicated by their gender-specific partial associations with the different subjective well-being measures. The unexplained part also captures potential gender differences due to other unobserved factors, which are reflected in gender differences in the intercepts of the regression.

4 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents sample summary statistics by gender and corresponding gender differences in characteristics for the pooled sample as well as for each country. We observe that individual characteristics and life circumstances of men and women differ widely in our sample. To begin with, women are considerably less likely to be married in all countries, which may reflect the fact that they generally live longer and marry older men, resulting in earlier and more frequent widowhood. We also observe small differences in household composition, where women appear to live in smaller households (which may also be linked to the higher likelihood of being a widow). In addition, older women generally have lower socio-economic status than older men: Older women are significantly less educated and less likely to work compared to older men. Everywhere but in India and China, women are more likely to be in the two lowest quartiles of the household permanent income distribution and less likely to be in the highest quartile. Moreover, women appear to have significantly worse health than men, as indicated by higher levels of both disability score and self-assessed pain. Finally, women are less likely to report trusting others or feeling safe in their neighborhoods than men, and tend be less involved in community activities in all countries but South Africa and Russia.

5 Results

5.1 Age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted partial associations

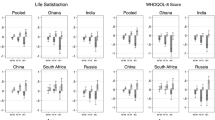

Figure 1 contrasts our estimates of the age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted partial associations between gender and each of our four measures of subjective well-being. We observe that the age-adjusted partial associations of being a woman with all four measures is negative in all countries, and statistically significantly so in most cases. However, once we control for a larger set of individual characteristics and life circumstances, we notice a reversal of the partial association between being female and both measures of evaluative well-being (the associations become positive – although not always statistically significantly – everywhere, except for WHOQoL-8 in Russia). Meanwhile, the partial associations between being female and emotional well-being measures remain negative but get smaller (and mostly statistically insignificant at the 5% level) when moving from the age-adjusted to the multivariable-adjusted models.

Partial associations between female and the four measures of emotional well-being (Life Satisfaction, WHO Quality of Life, Emotion Score and Experienced Utility) for the pooled sample and each country individually. Each coefficient is represented by a box and a 95% confidence interval. The dark boxes represent the female coefficients in age-adjusted regressions while the light boxes represent the female coefficients of the multivariable-adjusted regressions

Figure B1 in the Online Appendix further shows that our results are robust to a different construction of the Emotion Score measure, which does not include reports of physical issues (i.e., physical pain, sleepiness, stomach ache, headache).

In order to analyze the role of gender differences in individual characteristics and life circumstances to account for differences in subjective well-being, we further investigate the detailed associations in the age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted regressions in Tables 2–5 below. However, for conciseness, we will limit our below discussion to consistently significant associations only. As stated earlier, all measures of subjective well-being are standardized at the country level. We thus interpret coefficients in terms of multiples of standard-deviation units (SDU) within the country-specific distributions of the subjective well-being measure under consideration.

Tables 2 and 3 present the details of the age-adjusted (Panel A) and multivariable-adjusted (Panel B) models linking gender with evaluative measures of subjective well-being: Life Satisfaction and the WHOQoL-8 index, respectively. Examining the impact of other explanatory variables, we notice that higher income levels (and belonging to the highest income quartile in particular) increase both Life Satisfaction (with coefficients ranging from 0.31 to 0.62 SDU) and the WHOQoL-8 index (coefficients ranging from 0.27 to 0.73 SDU). Similarly, working is positively associated with Life Satisfaction in Ghana (0.09 SDU) and China (0.13 SDU), and with the WHOQoL-8 index (from 0.11 to 0.19 SDU) in all countries but Russia. In addition, health status seems to play an important part in evaluative well-being. In particular, higher WHO disability index scores are associated with both reduced Life Satisfaction (coefficients ranging from 0.24 to 0.41 SDU) and lower levels of the WHOQoL-8 indices (between −0.33 and −0.49 SDU). Finally, variables reflecting social cohesion, such as level of community involvement, trust in others, and feeling of safety in one’s neighborhood are almost always positively associated with Life Satisfaction (ranging from −0.04 to 0.16 SDU) and the WHOQoL-8 index (from −0.02 to 0.12 SDU). By means of comparison, the association of gender with Life Satisfaction (between 0.00 and 0.16 SDU) and with the WHOQOL-8 index (between −0.06 and 0.19 SDU) is approximately between 2 and 7 times smaller than the associations of a one standard deviation increase in the WHO disability index and of belonging to the highest quartile of permanent income, the two variables with the largest associations with evaluative well-being.

Tables 4 and 5 show the detailed estimation results of the age-adjusted (Panel A) and multivariable-adjusted (Panel B) models linking gender with our two measures of emotional well-being: Emotion Score and Experienced Well-Being. We observe that being in the highest quartile of the income distribution is associated with higher levels of emotional well-being (from 0.14 to 0.3 SDU for Emotion Score and from 0.16 to 0.38 SDU for Experienced Well-Being), and that higher levels of disability are associated with lower levels of Emotion Score (between −0.01 and −0.33 SDU) and Experienced Well-Being (from −0.08 to −0.23 SDU). In addition, self-assessed pain scores are significantly negatively associated with both measures of emotional well-being (from −0.05 to −0.11 SDU), everywhere but in Ghana for Experienced Well-Being. Among the social cohesion variables, community involvement seems to be positively associated with the Emotion Score (coefficients ranging from 0.01 to 0.13 SDU), but only feeling safe in one’s neighborhood is consistently associated positively with both measures of emotional well-being (0.00 to 0.11 SDU for Emotion Score and 0.04 to 0.15 SDU for Experienced Well-Being). Moreover, we observe that working is either not or negatively associated with emotional well-being (with the exception of a strong positive association with Emotion Score (by 0.33 SDU) in Ghana). By means of comparison, the association between gender and emotional well-being variables range from −0.02 to −0.15 SDU for Emotion Score and from 0.00 to −0.10 SDU for Experienced Well-Being. The relationship between the two most important identified factors - i.e., belonging to the highest quartile of permanent income and the standardized WHO disability index - and emotional well-being is thus up to 24 times larger than the association between gender and emotional well-being in multivariable-adjusted models.

Finally, comparing ceteris paribus gender differences in each of our four subjective well-being measures, we observe that the multivariable-adjusted gender differences are generally largest for the WHO Quality of Life Index (between 0.12 and 0.35 SDU), followed by the Emotion Score (between 0.1 and 0.27 SDU), Life Satisfaction (between 0.08 and 0.18 SDU), and Experienced Well-Being (between 0.06 and 0.11 SDU).

Tables B1–B4 in the Online Appendix further investigate how the coefficient on female changes with age dummies and adding more controls variables by meaningful grouping in a telescoping sequence (no control, age, demographic, socio-economic, health, and community engagement variables). This analysis shows that all the control variable groups contribute to the higher experienced well-being of women, compared to the situation without controls. For all four measures, adding socio-economic and health variables led to the highest increase in women’s subjective well-being. Moreover, we confirm the robustness of our results to different age specifications, using 5-year age bands (Tables B5–B8 in the Online Appendix), as well as including a second order age polynomial (Tables B9–B12).

5.2 Decomposition analysis

We now decompose the differences in subjective well-being between men and women into two parts. Specifically, we assess how much of the gender gap in subjective well-being is attributable to differences in the objective conditions of men and women (“explained part”), and how much is attributable to differences in the way men and women react to the same objective conditions as well as to differences in intercepts that cannot be directly related to any of the variables included in our models (“unexplained part”).

Tables 10–13 in Appendix show the results of the regression analyses of our four subjective well-being measures on our larger set of explanatory variables separately by gender. The tables also highlight any differences in coefficients between the female and male regressions. Overall, we find no consistent differences in coefficients between men and women, which suggests limited gender-specific heterogeneity in the association between individual characteristics and life circumstances on the one hand and subjective well-being of men and women on the other.

Tables 6 and 7 present the Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions of Life Satisfaction and the WHO Quality of Life Index, respectively. For both measures, we find lower levels of evaluative well-being for women than for men. Gender differences in Life Satisfaction are statistically significant in all countries but South Africa and Russia, ranging from 0.08 to 0.18 SDU. The corresponding differences in the WHOQoL-8 are statistically significant in all countries and range between 0.12 and 0.35 SDU. Focusing on the decomposition, we note that most of the evaluative well-being gap is due to differences in individual characteristics and objective life circumstances (explained part), which play in favor of men (difference estimates ranging from 0.13 to 0.25 SDU for Life Satisfaction and from 0.17 to 0.40 SDU for WHOQoL-8). These results suggest that women’s evaluative well-being would increase if they had the endowments of men. Further examining the disaggregation of the decomposition by explanatory variable, we observe that differences in health status (i.e., older women reporting higher levels of disability and pain) account for most of the explained differences, followed by social cohesion variables (i.e., the fact that women are less involved in community activities, report less trust in others and perceive their neighborhoods as less safe) and income (i.e., the fact women tend to belong to households with lower income). In several countries (Ghana, China and South Africa for Life Satisfaction, and China and South Africa for WHOQoL-8), differences in marital status (i.e., the fact that women in our sample are less often married than men) also contribute to the explained gender differences in evaluative well-being. Meanwhile, differences due to the unexplained part of the decomposition appear to favor women, even if these are much smaller in magnitude than the explained differences, (between 0 and −0.09 SDU for Life Satisfaction, and between −0.02 and 0.11 SDU for WHOQoL-8). In other words, women’s evaluative well-being would decrease if they had men’s coefficients while keeping their endowments fixed. The unexplained part thus partially mitigates the evaluative well-being deficit of women. The disaggregation of the unexplained part by explanatory variable does not reveal a consistent role of any specific variable to account the subjective well-being gap. As shown in Tables 10 and 11, the relationship between explanatory variables and subjective well-being is generally similar for men and women. The fact that the unexplained part of the decomposition contributes to reducing the gender gap thus does not appear to be linked to differences in the way men and women react to or evaluate any specific objective circumstances. Differences in the unexplained part can thus be linked to general (as opposed to variable-specific) differences in optimism or resilience of one gender, or to differential reactions to unobserved factors that we are unable to control for in our models.

Tables 8 and 9 present the analogous decomposition results for the two measures of emotional well-being: Emotion Score and Experienced Well-Being, respectively. Again, we observe a statistically significant gender difference in Emotion Score in favor of men in all countries (ranging between 0.10 and 0.31 SDU). Similarly, women report lower Experienced Well-Being than men everywhere (with difference estimates going from 0.06 to 0.19 SDU), and this difference is statistically significant in all but two countries. Similar to the decomposition of evaluative well-being measures, most of women’s well-being deficit appears to be attributable to differences in endowments (i.e., the explained part). Indeed, the individual characteristics and life circumstances incorporated in the decomposition framework significantly contribute to the higher emotional well-being of men relative to women in all countries (estimates ranging from 0.09 to 0.23 SDU for Emotion Score and from 0.06 to 0.11 SDU for Experienced Well-Being). As is the case for evaluative well-being measures, the explained differences are mostly driven by differences in levels of disability and self-assessed pain. However, compared to what we observe for evaluative measures of subjective well-being, income levels do not seem to play an important role for gender differences in emotional well-being. Finally, we observe that all the unexplained differences in emotional well-being are either insignificant or positive (ranging between 0.01 and 0.10 SDU for Emotion Score and between −0.03 and 0.09 SDU for Experienced Well-Being), implying that these unexplained differences do not help mitigate the emotional well-being disadvantage of women. In India and in the pooled sample, the gender gap in Emotion Score would even significantly increase if women had men’s coefficients while keeping their endowments fixed. As in the case of evaluative well-being, the unexplained part does not seem to be triggered by any specific variable.

In summary, our results consistently indicate that women have significantly lower levels of both evaluative and emotional well-being than men of the same age, across different countries as well as across the four outcome variables. However, when controlling for life circumstances and individual characteristics, our multivariable-adjusted analysis shows a decrease in the subjective well-being gender gap in favor of men. Indeed, gender differences in Emotion Score largely decrease in absolute value, and the gender gap in Experienced Well-Being disappears in all countries altogether. Moreover, gender differences in evaluative well-being even turn to the favor women. While these positive differences are small and not always statistically significant in the case of the WHOQoL-8, they are both substantial and consistent across countries in the case of Life Satisfaction. These results suggest that the gender gap in subjective well-being in favor of men may result from objective disadvantages of women compared to men rather than being related to gender per se. Results from Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions further corroborate that the female disadvantage in subjective well-being is mainly linked to explained factors, notably poorer health and lower permanent income of women compared to men.

6 Discussion and conclusion

6.1 Evaluative well-being

Results from our age-adjusted analysis reveal that women generally have lower levels of evaluative well-being than men of the same age. This finding is in line with the literature on gender and evaluative well-being. For example, Pinquart and Sörensen (2001), in a meta-analysis of 300 international studies focusing on older adults (i.e., for which the mean age was 55 and older), find that older women report slightly, but significantly lower life satisfaction than older men in uncontrolled models. Other studies (e.g., Inglehart 2002, using data from 65 societies and all age groups) also provide descriptive evidence that men tend to be happier than women after middle-age.

Our multivariable-adjusted analysis shows that - given similar individual characteristics and life circumstances - older women have equal or even slightly higher evaluative well-being than older men. This pattern suggests that gender per se or gender-related reporting differences are unlikely to be the main drivers behind the old-age gender gap in evaluative well-being found in age-adjusted models, and that this gap can instead be explained by the generally less favorable individual characteristics and life circumstances of older women compared to older men. In particular, we observe that better health and higher income are among the most important factors associated with higher levels of evaluative well-being, and that women generally report worse health and living in poorer households. Our findings corroborate previous results on the same topic. For example, Pinquart and Sörensen (2001) point out that gender explains less than 1% of the variance of their happiness measure, and argue that the gender happiness-gap may be explained by a disadvantage of older women in terms of socio-economic status, widowhood, health and every day competence. Similarly, Easterlin (2003) - based on several cohorts of the General Social Survey in the USA focusing on individuals aged between 32 and 88 years - shows that the happiness differential in the older population (aged 50 and older) is reversed when work and marital status are controlled for. He suggests that the unadjusted gender gap in subjective well-being in favor of men may be due to demographic changes in the older population, and in particular to the fact that women are more likely to suffer the adverse effects of widowhood. At the same time, the author argues that men’s well-being may be disproportionally improved by the positive effect of retirement, while this is less significant for women due to their lower rate of employment.

6.2 Emotional well-being

When adjusting only for age, our results show that women tend to report lower levels of emotional well-being than men. Similarly, descriptive evidence from the World Happiness Report (Fortin et al. 2015) – based on Gallup World Poll data from adult populations in multiple countries across all continents – indicates that men start reporting positive emotions more frequently than women after middle-age. These authors also show that older women experience systematically higher levels of negative emotions than men. Although they do not consolidate positive and negative experiences into an affect balance score comparable to our measure of net affect, the observation that older women tend to experience fewer positive and more negative emotions than men, suggests that such an index would show a disadvantage of women in terms of emotional well-being.

However, in contrast to what we observe for evaluative well-being, our multivariable-adjusted analysis shows merely an attenuation of the gender gap in emotional well-being once we control for individual characteristics and life circumstances. Thus, given similar observable conditions, women’s emotional well-being remains lower or at best similar to that of men. One hypothesis for the remaining differences in emotional well-being in favor of men stems from the fact that men and women may be socialized to experience and express their affect differently (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema and Rusting 1999). We are unable to compare our results to others’ given the absence of evidence regarding the relationship between emotional well-being and gender among older persons when individual characteristics and life circumstances are controlled for.

6.3 Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions

Results from our Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions confirm our above findings that women are disadvantaged in terms of both evaluative and emotional well-being. Furthermore, we show that this disadvantage of women is mostly due to observable factors which are part of the explained part of the decomposition. Poor health, in particular, is strongly linked to the gender gap in both evaluative and emotional well-being. Reducing disability and pain among women could improve their subjective well-being and help close this gender gap. In addition, we observe that unexplained factors mitigate women’s evaluative well-being deficit, but play no part in the emotional well-being gap in most countries. The unexplained part of the decomposition picks up gender differences in the relationship between individual characteristics and life circumstances on the one hand, and subjective well-being on the other (such as intrinsic optimism/pessimism), but may also capture other unobserved factors that we fail to control for in our models. These results imply that, if women had the same regression coefficients as men while keeping their own individual characteristics and life circumstances, their evaluative well-being would decrease, whereas their emotional well-being would not change significantly. While what is sometimes referred to as “female optimism” thus contributes to improving women’s cognitive evaluation of their own life, it does not improve their daily emotional experiences.

To the best of our knowledge, no other study has performed a similar decomposition of gender differences in subjective wellbeing on a population of older adults from the developing world. Therefore, we can only compare our results to those of Arrosa and Gandelman (2016) who perform Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions to analyze the gender happiness gap in the general adult population, using data from the Gallup World Poll (average age of 40.1), the World Values Survey (average age of 40.3) and the European Social Survey (average age of 47). Opposite to our findings, they report a positive evaluative well-being gap in favor of women, and that most of the happiness gap cannot be explained by observables. They argue that some unexplained “female optimism” contributes to increasing women’s evaluative well-being relative to that of men. However, their results are in agreement with our findings that unexplained factors contribute to improving women’s evaluative well-being.

6.4 Relationship between subjective well-being and individual characteristics and life circumstances

Beyond gender, our study provides evidence on the relationship between individual characteristics and life circumstances on the one hand, and subjective well-being on the other. This allows us to assess whether evaluative and emotional well-being are driven by the same factors. We find that health status (and especially the disability index) displays by far the strongest association with subjective well-being in older adults. Secondly, household income also appears to play an important role for both evaluative and emotional well-being among older adults in the developing world. These results stand in contrast to previous findings in the literature. For example, Kahneman and Deaton (2010) show that, in the USA, higher income improves evaluative, but not emotional well-being in the general population. One possible explanation for this difference could lie in the fact that our sample is based in relatively poor countries, where only higher income may allow access to certain basic services (e.g. efficient transportation, health services, decent housing), the lack of which may impact daily affective experiences. Interestingly, our results show only one major difference in the association of life circumstances with evaluative and emotional well-being: working is positively associated with evaluative measures of subjective well-being, but negatively associated with emotional measures. This result is similar to findings by Knabe et al. (2010) - on a sample of working-age individuals in Germany - that employed and unemployed individuals have similar levels of emotional well-being, despite a significant gap in evaluative well-being. One potential explanation for this apparent inconsistency may be that working is often considered a rather unenjoyable activity and common source of stress and other negative emotions, but that work status is also an indicator of social status and personal achievement, thereby increasing evaluative well-being. While the literature often highlights widowhood as an important driver of gender differences in subjective well-being in older adults (e.g. Sobieszky et al. 2003 - based on data from individuals over 60 in Thailand; Easterlin 2003), we do not find consistent associations between marriage and subjective well-being across different countries.

6.5 Conclusion and limitations

Our study bears important conclusions which may inform further research as well as policy makers. We demonstrate a negative association between gender and both evaluative and emotional subjective well-being. However, as discussed earlier, this association appears to be mainly linked to individual characteristics and life circumstances, notably to women’s disadvantages in terms of health and income, rather than to intrinsic gender differences. These results imply that female-targeted policies should complement more general interventions aiming at improving the well-being of older adults. For example, the revaluation of widow’s entitlement or the distribution of non-contributory old-age pensions may improve the financial situation of older women, as well as foster their access to healthcare. In addition, life-long health-promoting policies, such as the provision of universal health insurance or the launch of awareness campaigns promoting a healthy lifestyle and regular medical check-ups for women, may go a long way towards decreasing gender inequities in terms of disability among older adults, and in turn translate into a reduction of the subjective well-being gap.

To our knowledge, we are the first to provide a comprehensive comparison of age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted analyses of the relationship between gender and well-being using multiple measures for evaluative and emotional well-being. In particular, the use of SAGE data allows us to explore the differences between these various measures using a large-scale multi-country dataset from the developing world. However, our approach based on cross-sections of observational data does not allow us to interpret any of our estimated associations as causal effects. In addition, it is of note that even our multivariable-adjusted models do not control for all the factors which may vary by gender and age and influence subjective well-being. More research is thus needed to address these limitations in order to allow inference of a causal relationship. In spite of these limitations, our study makes a valuable contribution to documenting gender differences in older adults from different developing country settings, and proposing ways of reflection and interpretation of these differences.

Availability of data and material

Available from WHO website.

Code availability

Available upon request.

Notes

Some definitions of subjective well-being also include the concept of “eudaimonic” well-being, which focuses on a person’s functioning and realization of her potential. (Kapteyn et al. 2015).

Specifically, data was collected between 2007 and 2010 in China, in 2007 and 2008 in Ghana, in 2007 in India, in 2007, 2008 and 2010 in Russia, and in 2007–2008 in South Africa.

Work: working, subsistence farming. Housework: preparing food, doing housework, watching children, shopping, providing care to someone. Travel: walking somewhere, traveling by bicycle, traveling by car/bus/train. Leisure: rest (including tea/coffee break), chatting with someone, playing (including cards/ games), reading, listening to radio, watching TV, exercising or leisure walk, other leisurely activity. Self-care: grooming or bathing (self), eating, religious activity, intimate relations/sex.

We construct household income quartiles based on SAGE’s permanent income variable as a proxy for living standards of individual household members.

Evidence shows that there may be strong income inequality within households, and that women are the poorer partner in a majority of cases (Haussen 2019).

References

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press.

Arrosa, M. L., & Gandelman, N. (2016). Happiness decomposition: female optimism. Journal Happiness Studies, 17(2), 731–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9618-8.

Baltes, P. B., & Baltes, M. M. (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: the model of selective optimization with compensation. In P. B. Baltes & M. M. Baltes (Eds), Successful aging (pp. 1–34). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511665684.003.

Bernasek, A., & Bajtelsmit, D. (2002). Predictors of women’s involvement in household financial decision-making. Financial Counseling and Planning, 13(2), 1–9.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science & Medicine, 66(8), 1733–1749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.030.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2009). The U-shape without controls: a response to Glenn. Social Science & Medicine, 69(4), 486–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.022.

Carstensen, L. L. (1995). Evidence for a life-span theory of socioemotional selectivity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4(5), 151–156. JSTOR.

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: a theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.54.3.165.

Carstensen, L. L., Turan, B., Scheibe, S., Ram, N., Ersner-Hershfield, H., Samanez-Larkin, G. R., Brooks, K. P., & Nesselroade, J. R. (2011). Emotional experience improves with age: evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychology and Aging, 26(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021285.

Case, A., & Paxson, C. H. (2005). Sex differences in morbidity and mortality. Demography, 42(2), 189–214. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2005.0011.

Chappell, N. L., & Havens, B. (1980). Old and female: testing the double Jeopardy hypothesis. The Sociological Quarterly, 21(2), 157–171. JSTOR.

Denton, M., Prus, S., & Walters, V. (2004). Gender differences in health: a Canadian study of the psychosocial, structural and behavioural determinants of health. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 58(12), 2585–2600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.008.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 403–425. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056.

Dolan, P., Kudrna, L., & Stone, A. (2017). The measure matters: an investigation of evaluative and experience-based measures of wellbeing in time use data. Social Indicators Research, 134(1), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1429-8.

Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Happiness of women and men in later life: nature, determinants, and prospects. In M. J. Sirgy, D. Rahtz, & A. C. Samli (Eds), Advances in quality-of-life theory and research (pp. 13–25). Netherlands: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-0387-1_2.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00235.x.

Flores, G., Kieny, C., & Maurer, J. (2020). Deconstructing gender differences in experienced well-being among older adults in the developing world: the roles of time use and activity-specific affective experiences. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02435-3.

Fortin, N., Helliwell, J. F., & Wang, S. (2015). How does subjective well-being vary around the 42 world by gender and age? (John F. Helliwell, Richard Layard, and Jeffrey Sachs). Sustainable Development Solutions Network. http://worldhappiness.report/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/04/WHR15.pdf.

Glenn, N. (2009). Is the apparent U-shape of well-being over the life course a result of inappropriate use of control variables? A commentary on Blanchflower and Oswald (66: 8, 2008, 1733–1749). Social Science & Medicine, 69(4), 481–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.038.

Grabka, M. M., Marcus, J., & Sierminska, E. (2015). Wealth distribution within couples. Review of Economics of the Household, 13(3), 459–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9229-2.

Haussen, T. (2019). Intra-household income inequality and preferences for redistribution. Review of Economics of the Household, 17(2), 499–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-018-9410-8.

Hyde, J. S. (2007). New directions in the study of gender similarities and differences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(5), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00516.x.

Inglehart, R. (2002). Gender, aging, and subjective well-being. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 43(3–5), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/002071520204300309.

Jayachandran, S. (2015). The roots of gender inequality in developing countries. Annual Review of Economics, 7(1), 63–88. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115404.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489–16493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011492107.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: the day reconstruction method. Science, 306(5702), 1776–1780. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1103572.

Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533006776526030.

Kahneman, D., & Riis, J. (2005). Living, and thinking about it: two perspectives on life. In F.A. Huppert, N. Baylis, & B. Keverne (Eds), The Science of Well-Being, (pp. 285−304). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198567523.003.0011.

Kapteyn, A., Lee, J., Tassot, C., Vonkova, H., & Zamarro, G. (2015). Dimensions of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 123(3), 625–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0753-0.

Kato, H., Asukai, N., Miyake, Y., Minakawa, K., & Nishiyama, A. (1996). Post-traumatic symptoms among younger and elderly evacuees in the early stages following the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji earthquake in Japan. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 93(6), 477–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10680.x.

Kieny, C., Flores, G., Ingenhaag, M., & Maurer, J. (2020). Healthy, wealthy, wise, and happy? Assessing age differences in evaluative and emotional well-being among mature adults from five low- and middle-income countries. Social Indicators Research, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02515-4.

Knabe, A., Rätzel, S., Schöb, R., & Weimann, J. (2010). Dissatisfied with life but having a good day: time-use and well-being of the unemployed. The Economic Journal, 120(547), 867–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02347.x.

Knodel, J., & Ofstedal, M. B. (2003). Gender and aging in the developing world: where are the men? Population and Development Review, 29(4), 677–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2003.00677.x.

Luhrmann, M., & Maurer, J. (2008). Who wears the trousers? A semiparametric analysis of decision power in couples. MEA Discussion Paper Series 08168. https://ideas.repec.org/p/mea/meawpa/08168.html.

Markides, K. S., & Black, S. A. (1996). Race, ethnicity, and aging: the impact of inequality. In R. H. Binstock, L. K. George, V. W. Marshall, G. C. Myers, & J. H. Schulz (Eds), Handbook of aging and the social sciences, 4th ed. (pp. 153–170). San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press.

Miret, M., Caballero, F. F., Mathur, A., Naidoo, N., Kowal, P., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., & Chatterji, S. (2012). Validation of a measure of subjective well-being: an abbreviated version of the day reconstruction method. PLoS ONE, 7(8), e43887 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043887.

Neumark, D. (1988). Employers’ discriminatory behavior and the estimation of wage discrimination. The Journal of Human Resources, 23(3), 279–295. https://doi.org/10.2307/145830. JSTOR.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Rusting, C. L. (1999). Gender differences in well-being. In D. Kahneman, Ed. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds), Well-being: the foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 330–350). New York, NY, USA: Russell Sage Foundation.

OECD. (2013). How’s life? 2013: measuring well-being (OECD Publishing). https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201392-en.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2001). Gender differences in self-concept and psychological well-being in old age: a meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(4), P195–213.

Power, M. (2003). Development of a common instrument for quality of life. In A. Nosikov & C. Gudex (Eds), EUROHIS: developing common instruments for health surveys (pp. 145–163). Amsterdam, Netherlands: IOS Press.

Quisumbing, A. R., Haddad, L., & Peña, C. (2001). Are women overrepresented among the poor? An analysis of poverty in 10 developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 66(1), 225–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(01)00152-3.

Sobieszczyk, T., Knodel, J., & Chayovan, N. (2003). Gender and wellbeing among older people: evidence from Thailand. Ageing and Society, 23(06), 701–735. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X03001429.

Solon, G., Haider, S., & Wooldridge, J. (2013). What are we weighting for? (No. w18859). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w18859.

Stone, A. A., Schwartz, J. E., Broderick, J. E., & Deaton, A. (2010). A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(22), 9985–9990. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1003744107.

Stotsky, J. G., Shibuya, S., Kolovich, L., & Kebhaj, S. (2016). Trends in gender equality and women’s advancement. International Monetary Fund - IMF Working Paper - Research Department and Strategy, Policy, and Review Department. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp1621.pdf.

Ticehurst, S., Webster, R. A., Carr, V. J., & Lewin, T. J. (1996). The psychosocial impact of an earthquake on the elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(11), 943–951. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199611)11:11<943::AID-GPS412>3.0.CO;2-B.

United Nations. (2018). The sustainable development goals report 2018. United Nations. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/progress-report.

Verbrugge, L. M. (1985). Gender and health: an update on hypotheses and evidence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 26(3), 156–182.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Lausanne.

Funding

J.M. acknowledges support for this research by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the Swiss National Science Foundation through the Swiss Programme for Research on Global Issues for Development (r4d programme) by the grant “Inclusive social protection for chronic health problems” (Grant number: 400640_160374).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kieny, C., Flores, G. & Maurer, J. Assessing and decomposing gender differences in evaluative and emotional well-being among older adults in the developing world. Rev Econ Household 19, 189–221 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09521-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09521-y

Keywords

- Subjective well-being

- Evaluative well-being

- Emotional well-being

- Gender

- Low- and middle-income countries

- Decomposition analysis