Abstract

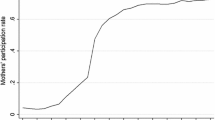

This paper analyses how maternal labor supply relates to the availability of childcare services in Flanders, a region that has a fairly abundant service provision, but does not offer a service guarantee as in several Nordic countries. Variation in price/quantity bundles that stems from the interplay of three types of childcare services are used to identify mothers’ labor supply responses. The estimates indicate that policy measures which increase the availability may exhibit large labor supply effects. Moreover, budgetary simulations suggest the expansion of subsidised care services to be beneficial to the exchequer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Herbst (2010) for a more recent study on labor supply effects on childcare costs for the US.

Note that the part-time nature of demand for childcare does not warrant a simple equation of the coverage rate with the employment rate of mothers. In effect, a full-time childcare slot may cover for more than one child. As a rule of thumb, the Flemish childcare authority ‘Kind en Gezin’ assumes in its planning exercises that a full-time slot can cover the demand of 1.2 children.

We use the Flemish Families and Care Survey (FFCS) data for these estimations. This dataset is described in detail in Sect. 5. It should be noted that, to obtain maximum reliability, estimation was done on the largest possible dataset (N = 870), representative of all types of households with small children in Flanders, thus including single parents households and households with an unemployed father. The table, however, reflects only the couple households of the target population of this paper.

As a sensitivity analysis, we looked at the percentage of parents experiencing supply to be restricted, when taking other limits than 50 %. If we take 30 %, the percentage of parents living in such a situation drops to 2.5 %. This number raises to 4 % when taking 40 and 11 % when taking 60 and 19 % when taking 70 %.

In contrast to Van Soest (1995), we have chosen not to include alternative specific constants as it is relatively hard to give a meaningful interpretation to these constants in terms of preferences.

In order to keep the extended labour supply model relatively simple, we have assumed that preferences only differ across individuals by observed heterogeneity. As such, we neglect household specific heterogeneity which is unobserved (Hansen and Liu 2011). We assume that all unobserved effects are captured by the stochastic term \(\epsilon _{i,j}\) of total household utility. Haan (2006) showed that relatively simple models of this kind tend to perform well in labor force participation predictions, which is also illustrated by our case (see below).

For more information about the FFCS, see Debacker et al. (2006).

195 households are dropped for reasons of programming in EUROMOD. 112 households are dropped because they either report hours worked or reported income, but not both.

Not working equals the interval [0,10] h/week, part-time is equal to [11,25] h/week, 4/5 to [26,35] h/week and full-time reflects the interval [35,50] h/week.

The empirical data of the FFCS support this assumption. Only 6 % of the parents with a child younger than three actually stated to be able to do without childcare services because they were using flexible working hours to organize care by themselves (Ghysels and Debacker 2007: 57).

More information about Euromod can be found at https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/euromod.

Taste shifters in the preference for consumption were not significant and were therefore dropped from the estimation.

Only the gross hourly wage of the mother is raised with 10 %, the gross wage of the father remains constant. When changing the monetary cost of childcare, both the cost of formal subsidized and non-subsidized childcare is increased with 10 %.

Note that it is obvious that a 10 % increase in gross hourly wages leads to higher labour supply responses than a 10 % decrease in childcare prices as the change in the budget constraint is considerably higher in the former counterfactual. For full-time working mothers, raising her gross wage with 10 % raises, on average, the monthly disposable household income with 123 Euro. Raising the cost of childcare with 10 % diminishes, on average, the monthly disposable household income with 18 Euro. If we would decrease childcare costs by the same amount as the increase in wages, similar labour supply effects would be observed as both effects have a similar effect on the budgetconstraint of households.

We assume that the supply of childcare is flexible enough to cover this limited increase in demand. However, we can not completely rule out that this reform also necessitates a slight increase in childcare capacity.

As mentioned in chapter 3.4, we assume that parents experience labor inhibiting restrictions when they have a predicted probability of a childcare offer (any type) of less than 50 %. 7 % of the parents in our sample are in this situation. When taking another limit, e.g. 40 %, this amounts drops to 4%. Looking at the impact of our results when taking this new limit, we notice a predicted labor force participation of mothers in the baseline of 83.5 %. Consequently, moving away from the standard tipping point in probability analysis (50 %) comes at a cost of a loss in predictive efficacy, keeping in mind that the observed labor force participation is 80.6 % and the prediction at 50 % is 81.5 %. Therefore, we maintain the 50% threshold in the main analysis. Yet, a sensitivity analysis regarding the use of other thresholds can be found in the online Appendix.

A full day of formal subsidized childcare costs the government 20.65 Euro per month (in 2005 prices). This amount is based on internal information of ’Kind en Gezin’ and does for example not take into account the cost of new buildings. 1.0 million Euro/month might thus be an underestimation of the real governmental cost.

References

Aaberge, R., Colombino, U., & Strom, S. (1999). Labour supply in Italy: An empirical analysis of joint household decisions, with taxes and quantity constraints. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 14(4), 403–422.

Aassve, A., & Meroni, E. P. C. (2012). Grandparenting and childbearing in the extended family. European Journal of Population, 28(4), 499–518.

Anderson, P. M., & Levine, P. B. (1999). Child Care and mothers’ employment decisions, NBER Working Paper Series, 7058.

Arrufat, J. L., & Zabalza, A. (1986). Female labor Supply with taxation. Random Preferences, and Optimization Errors, Econometrica, 54, 47–63.

Bargain, O., & Orsini, K. (2006). In-work policies in Europe: Killing two birds with one stone? Labour Economics, 13, 667–697.

Bettens, C., Buysse, B., & Govaert, K. (2002). Enquete inzake het gebruik van Kinderopvang voor kinderen jonger dan drie jaar.

Blau, D. M., & Robins, P. K. (1988). Child-care costs and family labor supply. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 70(3), 374–381.

Blundell, R., & Macurdy, T. (1999). Labor supply: A review of alternative approaches. Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, 1559–1695.

Boca, D. D. (2002). The effect of child care and part time opportunities on participation and fertility decisions in Italy. Journal of Population Economics, 15(3), 549–573.

Boca, D. D., & Vuri, D. (2007). The mismatch between employment and child care in Italy: The impact of rationing. Journal of Population Economics, 20(4), 805–832.

Brewer, M., & Paull, G. (2004). Families and children strategic analysis programme (FACSAP). Reviewing approaches to understanding the link between childcare use and mothers’ employment, DWP Working Paper No. 14.

Brilli, Y., Del Boca, D., & Pronzato, C. (2013). Does child care availability play a role in maternal employment and childrens development? (p. 125). Evidence from Italy, Review of Economics of the Household.

Debacker, M., Ghysels, J., & Van Vlasselaer, E. (2006). Gezinnen, Zorg en opvang in Vlaanderen (GEZO), Technical Report CSB.

Ghysels, J., & Debacker, M. (2007). Zorgen voor kinderen in Vlaanderen: een dagelijkse evenwichtsoefening?. Leuven: Acco.

Gong, X., Breunig, R. & King, A. (2010). How responsive is female labour supply to child care costs: New Australian estimates, IZA Discussion Papers, 5119.

Haan, P. (2006). Much ado about nothing: Conditional logit vs. random coefficient models for estimating labour supply elasticities. Applied Economics Letters, 13(4), 251–256.

Haan, P., & Wrohlich, K. (2011). Can child care policy encourage employment and fertility? Evidence from a structural model. Labour Economics, 18(4), 498–512.

Hank, K., & Buber, I. (2009). Grandparents caring for their grandchildren: Findings from the 2004 Survey on Health. Ageing and Retirement in Europe, Journal of Family Issues, 30(1), 53–73.

Hansen, J., & Liu, X. (2011). Estimating labor supply responses and welfare participation: Using a natural experiment to validate a structural labor supply model, IZA Discussion Paper No. 5718.

Hardoy, I., & Schone, P. (2013). Enticing even higher female labor supply: The impact of cheaper day care. Review of Economics of the Household. doi:10.1007/s11150-013-9215-8.

Hausman, J. A., & Ruud, P. (1986). Family labor supply with taxes. American Economic Review, 74, 242–248.

Hedebouw, G., & Peetermans, A. (2009). Het gebruik van opvang voor kinderen jonger dan 3 jaar in het Vlaams Gewest (p. 239). Leuven: Steunpunt Welzijn, Volksgezondheid en Gezin.

Herbst, C. (2010). The labor supply effects of child care costs and wages in the presence of subsidies and the earned income tax credit. Review of Economics of the Household, 8(2), 199–230.

Kalb, G. (2009). Children, labour supply and child care: Challenges for empirical analysis. Australian Economic Review, 42(3), 276–299.

Keane, M., & Rogerson, R. (2012). Micro and macro labor supply elasticities: A reassessment of conventional wisdom. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(2), 464–476.

Kornstad, T., & Thoresen, T. O. (2007). A discrete choice model for labor supply and child care. Journal of Population Economics, 20(4), 781–803.

Kreyenfeld, M., & Hank, K. (2000). Does the availability of child care influence the employment of mothers? Findings from Western Germany, Population Research and Policy Review, 19, 317–337.

Lokshin, M. (2004). Household childcare choices and womens work behavior in Russia. Journal of Human Resources, 39, 1094–1115.

Mahringer, H., & Zulehner, C. (2013). Child-care costs and mothers employment rates: An empirical analysis for Austria. Review of Economics of the Household. doi:10.1007/s11150-013-9222-9.

Market Analysis and Synthesis (MAS) (2007). Analyse van het zoekproces van ouders naar een voorschoolse kinderopvangplaats. Leuven:MAS/Kind en Gezin.

MCFadden, D. (1974). Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. Frontiers in Econmetrics, Chapter 4.

Mocan, N. (2007). Can consumers detect lemons? An empirical analysis of information asymmetry in the market for child care. Journal of Population Economics, 20(4), 743–780.

Poirier, D. J. (1980). Partial observability in bivariate probit models. Journal of Econometrics, 12(2), 209–217.

Ribar, D. C. (1995). A structural model of child care and the labor supply of married women. Journal of Labor Economics, 13(3), 558–597.

Uhlenberg, P., & Hammill, B. (1998). Frequency of grandparent contact with grandchild sets: Six factors that make a difference. The Gerontologist, 38, 276.

Van Klaveren, C., & Ghysels, J. (2012). Collective labor supply and child care expenditures: Theory and application. Journal of Labor Research, 33, 196–224. doi:10.1007/s12122-011-9127-4.

Van Soest, A. (1995). Structural models of family labor supply: A discrete choice approach. The Journal of Human Resources, 30(1), 63–88.

Viitanen, T. K., & Chevalier, A. (2003). The supply of childcare in Britain: Do mothers queue for childcare?, Royal Economic Society Annual Conference 2003 211, Royal Economic Society.

Wrohlich, K. (2004). Child care costs and mothers labor supply: An empirical analysis for Germany, Discussion Papers of DIW Berlin 412, DIW Berlin, German Institute for Economic Research.

Wrohlich, K. (2008). The excess demand for subsidized child care in Germany. Applied Economics, 40(10), 1217–1228.

Wrohlich, K. (2011). Labor supply and child care choices in a rationed child care market. Discussion Papers of DIW Berlin 1169, DIW Berlin, German Institute for Economic Research.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the editor and two referees for their comments and suggestions that have greatly improved the present contribtion. Furthermore we acknowledge support from the participants of the IMPROVE workshop at CHILD in Turin, 1 October 2012, of the Microsimulation research workshop in Bucharest, 11–12 October 2012, of the PE-ETE seminar in Leuven, 15 November 2012 of the CSB seminar, 19 April 2013 and the 2013 EALE conference (September 2013). The usual disclaimer applies. We have benefited from financial support from IWT Flanders in the SBO-project ’FLEMOSI: A tool for ex ante evaluation of socio-economic policies in Flanders’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

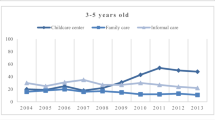

Appendix: Basic descriptives

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vandelannoote, D., Vanleenhove, P., Decoster, A. et al. Maternal employment: the impact of triple rationing in childcare. Rev Econ Household 13, 685–707 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-014-9277-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-014-9277-2