Abstract

Preferences, including preferences for children, are shaped during the formative years of childhood. It is therefore essential to include exposure to religious practice during childhood in an attempt to establish a link between religiosity and fertility. This path has not been explored in the documented literature that looks at the relationship between current religiosity and fertility. The International Social Survey Programme: Religion II (ISSP) provides the data base. It includes information on maternal/paternal/own mass participation when the respondent was a child (nine levels each), as well as on his current churchgoing (six levels) and prayer habits (eleven levels). These variables are included as explanatory variables in ‘fertility equations’ that explain the number of children of Catholic women in Spain and Italy. The core findings are that exposure to religiosity during the formative years of childhood, has a pronounced effect on women’s ‘taste for children’ that later on translates into the number of her offspring. In Spain, the two parents have major opposite effects on women. Most striking is the negative effect of the mother’s intensity of church attendance on her daughter’s fertility: Women who were raised by an intensively practicing mother have on average one child less that their counterparts who were raised by a less religious mother. On the other hand, an intensively practicing father encourages the daughter to have more children (by about 0.8, on average). The Italian sample confirms the statistically significant negative effect of the mother’s religiosity. The father’s religious conduct has apparently no effect on Italian women’s birth rates. Current religiosity seems to be irrelevant, both in Spain and in Italy. It follows that religiosity and fertility are interrelated but the mechanism is probably different from the simplistic causality that is suggested in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In Spain: Birth rates dropped from 3 children in the mid 1950s, to 2.8 in 1975, and to a mere 1.2 in recent years. The very sharp drop started in 1975 (at the onset of democracy) and followed a constant sliding path till the late 1990s when it stabilized at a rate of 1.2 children (Fernández-Cordón, 1998a). In Italy: Birth rates dropped from 2.4 in 1970 to 1.2 in 2000 (Fejka & Westoff, 2006). The decrease in birth rates is evident in many other European countries, but Spain and Italy have suffered the sharpest changes (McDevitt, 1999; Sleebos, 2003; Perez & Livi-Bacci, 1992).

Similarly, reciprocal effects also exist between religiosity and other family behaviour dimensions such as: marriage; divorce; non-marital cohabitation; and premarital sex.

And also a series of socio-economic background variables that might affect fertility: age, education, region of residence and population size in place of residence.

We do not look at inter-denominational comparisons. Such comparisons are more relevant in a pluralistic society- Spain and Italy have one major religion and almost 90% of the population is Catholic (see Brañas-Garza & Neuman, 2004, 2006, for a more detailed analysis for Spain; and Introvigne & Stark 2005, for Italy).

To account for the fact that women in the sample may not have yet completed their childbearing age, the ‘age’ variable will be included in the regression analysis.

Moreover, in Spain according to the Constitution, parents are obliged to pay for the education of their children, also of those children who are no longer minors (Picontó-Novales, 1997: 113).

Assume that the true regression model is y = bx + u and the observed y (denoted by y*) has a measurement error, so that y* = y + e. It follows that the estimated regression model is y* = bx + u + e. As long as the measurement error in y*, which is e, is not correlated with x, OLS yields unbiased and consistent estimates.

For instance: 431 respondents (17% of the total sample) did not report the number of years of schooling; 441 respondents (18%) did not answer the question on current participation in mass services; 248 respondents (10%) skipped the question of paternal mass attendance.

For instance: 108 respondents (11% of the total sample) did not report the number of years of schooling; 98 respondents (10%) did not answer the question on paternal mass attendance.

In the Spanish data set: Three women report a non-Catholic mother, nine had a non-Catholic father and 12 women are married to a non-Catholic spouse. In the Italian sample: one had a non-Catholic mother, two had a non-Catholic father and seven are married to a non-Catholic spouse.

The sample averages in the two countries are larger than the birth rate in 1998 (that was 1.2 children, both in Spain and in Italy), because the samples include respondents who gave birth during the last 3 decades, when birth rates were higher.

Based on the ISSP questions, for the mother/the father/and the child at the age of 12: “When you were a child (or, 12 years old, for own childhood mass attendance), how often did your mother/ father/yourself attend mass services at the church?” The options are: Never (1); once a year (2); one or two times a year (3); a few times a year (4); once a month (5); two or three times a month (6), almost every week (7); every week (8); several times a week (9).

Current church attendance is derived from the following ISSP question: “How often do you attend mass services at the church?” The answer includes 6 alternative options: Never (1); once a year (2); one or two times a year (3); once a month (4); two or three times a month (5); and, every week (6). Prayer habits are derived from the question: “How often do you pray?” The possible answers are: never (1); once a year (2); twice a year (3); few times a year (4); once a month (5); two or three times a month (6); almost every week (7); every week (8); several times a week (9); once a day (10); and several times a day (11).

While our sample is composed of women younger than 46, this figure relates to a sample of the two genders with no age restrictions. Men are less active than women but on the other hand older individuals tend to be more active.

Introvigne and Stark, (2005) argue that this is due to more religious competition: “The rapid development of a highly visible competitiveness in Italian relgious economy and the rise of competition within Roman Catolicism have spurred a substantial religious revival” (p. 4).

Respect for the intensively practicing father will be further enhanced by the daughters if more religious men are nicer to their wives and give them higher ‘quasi-wages’ for their within-household activities (Grossbard-Shechtman, 1993).

In Equation #1 it is marginally significant, at a significance level of 11.2%: Women who were intensively exposed to mass services have on average 0.5 children more than those who had a low- or medium- exposure.

The correlation coefficients between the paternal, maternal and child’s mass participation levels (nine levels) are: 0.6807 between the mother’s and father’s levels; 0.5464 between the mother’s and child’s church attendance levels; and 0.4578 between the father’s and the child’s respective levels.

We also experimented with interaction terms between maternal/paternal and child’s intensity of practice- the basic core results did not change.

Experimenting with larger upper age limits did not lead to different results.

It is sometimes claimed that the dramatic raise in Spanish women’s educational attainments that took place during the last 30 years is responsible for the decline in birth rates (e.g. Adserá, 2006a). Our ‘fertility equations’ do not support this hypothesis.

Alternatively the ‘exposure’ option can be used in the Stata Poisson estimation. Specifying: exposure (lnage), while excluding the age independent variables, did not change the basic results.

The region dummy variables have a major contribution to the explanatory power of the regressions: when they are excluded from the regressions, R 2 drops to about half its size (not reported). The basic results that relate to the religiosity variables do not change (there are minor changes in the size and significance of coefficients. None of the insignificant variables becomes significant and the significant coefficients stay significant).

Instead of running two separate regressions for Spain and Italy, one pooled regression of the two samples can be used. To allow different coefficients in the two countries the pooled regression should include, in addition to the set of explanatory variables, also a dummy variable for Italy and interactions of all variables with the dummy variable for Italy. From the results of this interactive pooled regression we can then derive the two separate equations (presented in Tables 2, 4). The coefficients of a pooled regression that does not include the interactive variables are estimates of weighted mean effects for the combined sample. Estimation of this restricted fertility equation reassures the significance of the negative coefficient of a highly religious mother (Z = 2.11) and the insignificance of the current religiosity measures.

Guiso, Sapienza, & Zingales, 2003 use a similar argument to explain the effect of religiosity (of countries) on economic performance.

There is a correlation coefficient of 0.6311 between maternal and paternal church attendance. A religious mother therefore implies (in most cases) a religious household.

Obviously there are many other factors that affect changes in birth rates, such as: macroeconomic variables, related transfer payments, education.

References

Adserá, A. (2006a). Differences in desired and actual fertility: An economic analysis of the Spanish case. Review of Economics of the Household, 4(1), 75–95.

Adserá, A. (2006b). Marital fertility and religion: Recent changes in Spain, 1985 and 1999. Population Studies, 60(2), 205–221.

Amin, S., Diamond, I., & Steele, F. (1997). Contraception and religiosity in Bangladesh. In G. W. Jones, R. M. Douglas, J. C. Caldwell, & R. M. D’Souza (Eds.), The continuing demographic transition (pp. 268–289). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Al-Qudsi, S. (1998). The demand for children in Arab countries: Evidence from panel and count data models. Journal of Population Economics, 11(3), 435–452.

Borooah, V. K. (2004). The politics of demography: A study of Inter-Community Fertility Differences in India. European Journal of Political Economy, 20(3), 551–578.

Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (2000). Beyond the melting pot: Cultural transmission, marriage, and the evolution of ethnic and religious traits. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 955–988.

Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (2001). The economics of cultural transmission and the dynamics of preferences. Journal of Economic Theory, 97, 298–319.

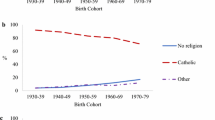

Brañas-Garza, P. (2004). Church attendance in Spain: Secularization and gender differences. Economics Bulletin, 26(1), 1–9.

Brañas-Garza, P., & Neuman, S., (2004). Analyzing religiosity within an economic framework: The case of Spanish Catholics. Review of Economics of the Household, 2(1), 5–22.

Brañas-Garza, P., & Neuman, S. (2006). Intergenerational transmission of ‘Religious Capital’: Evidence from Spain. IZA (Bonn): Discussion Paper No. 2183.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2006). The Intergenerational transmission of risk and trust attitudes. IZA (Bonn): Discussion Paper No. 2380.

Fernández-Cordón, J. A. (1998a). Proyección de la población española 1991–2026. Revisión 1997, FEDEA (Madrid) Documentos de Trabajo 1998–11.

Fernández-Cordón, J. A. (1998b). Spain: A year of political changes. In J. Ditch, H. Barnes, & J. Bradshaw (Eds.), European Observatory on National Family Policies. Europe: European Commission.

Frejka, T., & Westoff, C. F. (2006). Religion, religiousness and fertility in the US and in Europe. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Rostock, Germany): Working Paper No. 2006-013.

Greene, W. H. (2003). Econometric analysis, (5th edn.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. A. (1993). On the economics of marriage. Boulder Co.: Westview Press.

Grotenhuis, M., & Scheepers, P.(2001) Churches in Dutch: Causes of religious disaffiliation in the Netherlands, 1937–1995. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40(4), 591–606.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2003). People’s Opium? religion and economic attitudes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(1), 225–282.

Introvigne, M., & Stark, R. (2005). Religious competition and revival in Italy: Exploring European exceptionalism. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion, 1(1), Article 5.

Kalwij, A. (2000). The effect of female employment status on the presence and number of children. Journal of Population Economics, 13(2), 221–239.

Lehrer, E. L. (1996). Religion as a determinant of marital fertility. Journal of Population Economics, 9, 173–196.

Mayer, J., & Riphan, R. (2000). Fertility assimilation of immigrants: A varying coefficient count data model. Journal of Population Economics, 13(2), 241–261.

McDevitt, T. M. (1999). World population profile: 1998. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Morgan, S., Stash, S., Smith, H. L., & Mason, K. O. (2002). Muslim and non-muslim differences in female autonomy and fertility: Evidence from four Asian countries. Population and Development Review, 28(3), 515–537.

Mosher, W., & Hendershot, G. (1984). Religion and fertility: A replication. Demography, 21(2), 185–191.

Neuman, S. (2007, forthcoming). Is religiosity indeed related to fertility. Population Studies.

Neuman, S., & Ziderman, A. (1986). How does fertility relate to religiosity: Survey evidence from Israel. Sociology and Social Research, 70(2), 178–180.

Oinonen, E. (2000). Nations’ different families? Contrasting comparison of Finnish and Spanish ‘Ideological Families’, MZES (Mannheim): Discussion Paper No. 15–2000.

Perez, M. D., & Livi-Bacci, M. (1992). Fertility in Italy and Spain: The lowest in the World. Family Planning Perspective, 24(4), 162–171.

Picontó-Novales, T. (1997). Family law and family policy in Spain, In J. Kurczewski & M. Maclean (Eds.), Family law and family policy in the New Europe. Dartmouth: Aldershot.

Sander, W. (1992). Catholicism and the economics of fertility. Population Studies, 46, 477–489.

Schellekens, J., & van Poppel, F. (2006). Religious differentials in marital fertility in The Hague. Population Studies, 60(1), 23–38.

Sleebos, J. (2003). Low Fertility Rates in OECD countries: facts and policy responses, Paris (France): OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 13.

Stolzenberg, R. M., Blair-Loy, M., & Waite, L. J. (1995). Religious participation over the life course: Age and family life cycle effects on church membership. American Sociological Review, 60(2), 84–103.

Thornton, A., Axinn, W. G., & Hill, D. H. (1992). Reciprocal effects of religiosity, cohabitation and marriage. American Journal of Sociology, 98(3), 628–651.

Tilley, J. R. (2003). Secularization and aging in Britain: Does family formation cause greater religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(2), 269–278.

Voas, D., & Crockett, A. (2005). Religion in Britain: Neither believing nor belonging, Sociology, 39(1), 11–28.

Wang, W., & Famoye, F. (1997). Modelling household fertility decisions with generalized Poisson regression. Journal of Population Economics, 10(3), 273–283.

Winkelmann, R. (2000). Econometric analysis of count data. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Winkelmann, R., Zimmermann, K. F. (1994). Count data models for demographic data. Mathematical Population Studies, 4, 205–221.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the editor and two anonymous referees for very helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Spanish sample characteristics

Appendix: Spanish sample characteristics

Appendix Table 1 presents the socio-economic characteristics of the respondents in the Spanish and Italian samples that are composed of married young women.

The socio-economic background is very similar in the two countries.

The age distributions are similar. The age range is 22-45 in Spain and 20-45 in Italy. The average age is 35 in the two countries. About half of the women in Spain and Italy are in the age group of 31-to-40.

The average number of years of schooling is 11.2 in Spain and 11.5 in Italy.

Around 30% of respondents in the two samples live in small places that are populated by 10,000 inhabitants or less. In Italy, all these places are rural.

The regional distributions reflect the national distribution. In Spain, the largest shares live in Andalucia, Cataluña, Valencia, Madrid and Castilla Leon. The shares of Cantabria, La Rioja, Navarra and Baleares are the smallest. In Italy, over one third of the sample resides in the southern parts of the country, about half live in the northern parts and the rest 14% live in the center.

Appendix Table 2 presents the distributions of the number of children.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brañas-Garza, P., Neuman, S. Parental religiosity and daughters’ fertility: the case of Catholics in southern Europe. Rev Econ Household 5, 305–327 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-007-9011-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-007-9011-4