Abstract

It is well documented in literature that funding conditions have been subject to the undue influence of distorted incentives of banks to lend and borrow at quarter ends under the Basel III regulatory framework. We investigate whether or not funding risk possibly also suffers the same. Using a state space model, we find quarter-end spikes in the Japanese yen Libor-OIS spread, which arguably reflect a higher funding risk premium at quarter ends, during the global financial crisis and in recent years. The phenomenon in the former episode suggests that quarter-end reporting under Basel II might already have had an effect on the functioning of funding markets, as banks found the capital ratio requirement sharply more binding or constraining. The spikes in the latter episode, which are attributable to the effect of the leverage ratio requirement under Basel III, are found to be negative, partly reflecting the scarcity of high-quality collaterals against the backdrop of a large-scale asset-purchase programme introduced by the Bank of Japan and partly a negative interest rate environment. The evidence adds to the argument in favour of supervisory practices that require banks to report/disclose their average leverage ratio for the quarter instead of their ratio for the last day of the quarter. Indeed, despite the currently proposed reform, the capital ratio remains quarter-end-based, so there could still be quarter-end spikes in funding risk premium in times of financial adversity.

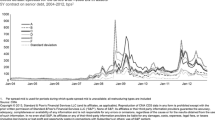

Source: Bloomberg and JPMorgan

Source: Bloomberg

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

What is reported, rather than when or the frequency at which it is reported, actually holds key to the potential influence on banks’ behaviour. As we shall discuss in the next section, their behaviour presumably should not change if they are required to report certain financial ratios as in their average in the quarter. It changes because they have to report the ratios as of the last day of the quarter, i.e., the supervisor takes only a snapshot of their balance sheet.

CGFS (2017) “observed that repo markets have recently been characterized by volatilities in prices and volumes over period-ends (quarter-end and year-ends). This is likely to be driven by incentives that banks face to ‘window-dress’ their balance sheets. These incentives include regulatory constraints, such as the leverage ratio, the G-SIB surcharge and the SRF levy, but also include commercial or taxation considerations”.

According to SWIFT, JPY’s share as a domestic and international payments currency was 3.3% in January 2019, trailing behind USD (40.1%), EUR (34.2%) and GBP (7.1%). According to the BIS Triennial Central Bank Survey in April 2016, JPY accounts for 11.0% of the total OTC foreign exchange turnover, second only to USD (44.1%) and EUR (15.6%).

The existence of paper currency, i.e., cash, provides depositors a choice to hold cash when a negative interest rate is applied. Therefore, ZLB is a theoretical boundary for policy rates to be effective. In reality, however, negative interest rate policy is feasible as there are costs associated with holding cash. Euro Area, Switzerland, Denmark and Japan once all entered a negative interest rate era.

Generally speaking, daily average is calculated for on-balance sheet assets and month-end average for off-balance sheet exposures.

UK authorities followed their US counterparts to require banks to report their quarterly average ratios at the end of the quarter from Q1 2017. UK banks used to submit their month-end ratios on a monthly basis.

Loans of the 3-month or longer tenor, no matter at which time of the quarter they are made, cannot escape from being captured by the snapshot at quarter ends and are thus not subject to the same distortive incentive.

That is, unless there are reasons to believe that counterparty risk is also subject to some quarterly influence.

For prudence, we’ve also employed another smoothing method, centred moving average, to de-trend the time series. The results remain largely unchanged.

A larger smoothing parameter generates a smoother trend line. For example, Ravn and Uhlig (2002) recommend to use 4 for the parameter instead of 2 for studying US business cycles. However, our analysis focuses on the deviations from the trend. If the trend is too smooth, the quarter-end spikes may be overstated during crisis times.

The repo market plays a key role in providing funding liquidity to banks. Repo transactions, which are collateralized by high quality liquid securities, are deemed free of counterparty credit risk such that repo rates can serve as a good proxy of funding condition.

As a robustness check, we performed analyses on an alternative version of the model to control for the GFC effect by introducing a dummy variable for the GFC period, on its own or interacting with the state variables, in each of the measurement equations. Based on the estimation results, the coefficients for the GFC dummy are statistically indifferent from zero and the remaining coefficients stay largely unchanged compared with our baseline model.

This is consistent with Brei and Gambacorta’s (2014) finding that the pro-cyclicality of total exposure is more pronounced than risk-weighted assets. Hence, the leverage ratio will decline for any given capital ratio during economic upturns but the other way round is true during economic downturns.

Christiansen et al. (2011) attribute the negative systematic risk for JPY to the currency’s safe haven nature. However, their theory cannot explain the phenomenon that negative spikes emerged only in a negative interest rate environment despite the fact that JPY has remained a safe haven currency for the whole sample period.

Lopez et al. (2018) find that banks experience significant loses in net interest income in a negative interest rate environment and are compensated by significant increases in fees, capital gains and gains in on securities and insurance. The losses in net interest income are driven by the non-reducing deposit expenses due to difficulty in cutting nominal deposit rates to below zero. Nucera et al. (2017) find that in a negative policy rate environment, some banks are more likely to become undercapitalised in a future potential crisis. Demiralp et al. (2017) argues that banks with higher excess liquidity suffer more from the negative rate policy and are more sensitive to further rate cuts in the negative range.

The feedback received at the CGFS study group’s Roundtable with market participants reveals that some players have faced considerable difficulties in placing cash, especially at quarter ends, sometimes to the extent that some counterparties refused to take cash via reverse repos at the any price.

The key change is to require banks to base their calculation of the leverage ratio on the average daily value over the quarter of adjusted gross securities financing transaction assets included in on-balance sheet exposures.

References

Arai, F., Makabe, Y., Okawara, Y., & Nagano, T. (2016). Recent trends in cross-currency basis. Bank of Japan Review, 16, 1–7.

Bank for International Settlements. (2010). 2010 FSI survey on the implementation of the new capital adequacy framework. Bank for international settlements occasional paper no. 9. https://www.bis.org/fsi/fsipapers09.pdf.

Bank for International Settlements. (2018). The financial sector: Post-crisis adjustment and pressure points. BIS annual economic report, chapter III (pp. 43–61).

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2018a). Statement on leverage ratio window-dressing behaviour. Bank for international settlements BCBS newsletter. Retrieved 18 October, from https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs_nl20.htm.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2018b). Implementation of basel standards: A report to G20 leaders on implementation of the Basel III regulatory reforms. Bank for international settlements BCBS, November, https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d453.pdf.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2018c). Revisions to leverage ratio disclosure requirements. Bank for international settlements BCBS consultative document, December, https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d456.pdf.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2019a). Sixteenth progress report on adoption of the Basel regulatory framework. Bank for international settlements BCBS, May, https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d464.pdf.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2019b). Revisions to leverage ratio disclosure requirements. Bank for international settlements BCBS, June, https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d468.pdf.

Bicu, A., Chen, L., & Elliott, D. (2017). The leverage ratio and liquidity in the gilt and repo markets. Bank of England staff working paper no. 690.

Borio, C. E., McCauley, R. N., McGuire, P., & Sushko, V. (2016). Covered interest parity lost: Understanding the cross-currency basis. BIS quarterly review, September 2016.

Brei, M. & Gambacorta, L. (2014). The leverage ratio over the cycle. Bank for international settlements working papers no. 471.

Christiansen, C., Ranaldo, A., & Söderlind, P. (2011). The time-varying systematic risk of carry trade strategies. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis,46(4), 1107–1125.

Committee on the Global Financial System. (2017). Repo market functioning. Bank for international settlements CGFS papers no. 59, https://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs59.pdf.

Demiralp, S., Eisenschmidt, J., & Vlassopoulos, T. (2017). Negative interest rates, excess liquidity and bank business models: Banks’ reaction to unconventional monetary policy in the euro area. Koç University-TUSIAD economic research forum working papers 1708.

Du, W., Tepper, A., & Verdelhan, A. (2018). Deviations from covered interest rate parity. The Journal of Finance,73(3), 915–957.

Egelhof, J., Martin, A., & Zinsmeister, N. (2017). Regulatory incentives and quarter-end dynamics in the repo market. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), August.

Griffiths, M. D., & Winters, D. B. (2005). The turn of the year in money markets: Tests of the risk-shifting window dressing and preferred habitat hypotheses. The Journal of Business,78(4), 1337–1364.

Hodrick, R. J., & Prescott, E. C. (1997). Postwar US Business Cycles: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Money, credit, and Banking,29, 1–16.

Hou, D., & Skeie, D. R. (2014). LIBOR: Origins, economics, crisis, scandal, and reform. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, (667).

Iida, T., Kimura, T., & Sudo, N. (2016). Regulatory reforms and the dollar funding of global banks: Evidence from the impact of monetary policy divergence. Bank of Japan working papers no. 16-E-14.

Karmakar, S., & Baptista, D. (2017). Understanding the Basel III leverage ratio requirement. Economic Bulletin and Financial Stability Report Articles and Banco de Portugal Economic Studies.

Kotomin, V., Smith, S. D., & Winters, D. B. (2008). Preferred habitat for liquidity in international short-term interest rates. Journal of Banking & Finance,32(2), 240–250.

Kotomin, V., & Winters, D. B. (2006). Quarter-end effects in banks: Preferred habitat or window dressing? Journal of Financial Services Research,29(1), 61–82.

Lopez, J. A., Rose, A. K., & Spiegel, M. M. (2018). Why have negative nominal interest rates had such a small effect on bank performance? Cross country evidence. NBER working paper no. 25004.

McAndrews, J., Sarkar, A., & Wang, Z. (2016). The effect of the term auction facility on the London interbank offered rate. Journal of Banking & Finance, 83, 135–152.

Michaud, F. L., & Upper, C. (2008). What drives interbank rates? Evidence from the Libor panel. International Banking and Financial Market Developments,3, 47.

Munyan, B. (2015). Regulatory arbitrage in repo market. US Department of the Treasury OFR working papers no. 15-22.

Nucera, F., Lucas, A., Schaumburg, J., & Schwaab, B. (2017). Do negative interest rates make banks less safe? Economics Letters,159, 112–115.

Ravn, M. O., & Uhlig, H. (2002). On adjusting the Hodrick-Prescott filter for the frequency of observations. Review of Economics and Statistics,84(2), 371–376.

Schwarz, K. (2018). Mind the gap: Disentangling credit and liquidity in risk spreads. The Wharton School University of Pennsylvania working papers.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank, without implicating, Richard Chu, Cho-hoi Hui, Theresa Kwan, Peter Lau, Zijun Liu, Giorgio Valente, Eric Wong and Jason Wu for invaluable comments and helpful discussions, and Max Kwong for excellent research assistance. We also gratefully acknowledge the referee’s insightful comments. The views expressed in this paper are the authors’ own, and do not necessarily represent those of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

The 1-week and one-month Libors are reported by ICE on every London working day at 11:55 am, based on submission from a panel of international banks. The 1-week and 1-month OIS rates are the closing bid prices obtained from Bloomberg at daily frequency. The JPY OIS is indexed to the Bank of Japan estimated unsecured overnight call rate. The general collateral repo rates are obtained from the DataQuery of JPMorgan Markets. The sample period spans 23 Jun 2005 to 12 Jun 2018, subject to data availability. Table 4 shows the summary statistics of the de-trended variables after applying the HP Filter as explained in Sect. 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kikuchi, M., Wong, A. & Zhang, J. Risk of window dressing: quarter-end spikes in the Japanese yen Libor-OIS spread. J Regul Econ 56, 149–166 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-019-09393-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-019-09393-w