Abstract

We study insurance take-up choices by consumers who face medical expense risk and who know they can default on medical bills by filing for bankruptcy. For a given bankruptcy system, we explore the total and distributional welfare effects of health insurance mandates compared with the pre-mandate market equilibrium. We consider different combinations of premium subsidies and out-of-insurance penalties, confining attention to budget-neutral policies. We show that when insurance mandates are enforced only through penalties, the efficient take-up level may be incomplete. However, if mandates are also supported with premium subsidies, full insurance coverage is efficient and can also be Pareto improving. Such policies are consistent with the incentive structure for insurance take-up set in the ACA. Pareto improvement is possible because the legal requirement that medical providers dispense acute care on credit, together with the bankruptcy option, yields effective subsidies for medical care utilized by the uninsured. Those subsidy funds, however, can serve the initially uninsured better when they are given as ex ante subsidies on insurance premiums.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to the 1986 Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act ( EMTALA).

On January 2015, the New York Times reported the results of a survey conducted by the Commonwealth Fund, finding a significant decrease in the uninsured rate and in financial distress due to medical bills in 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/15/upshot/financial-distress-connected-to-medical-bills-shows-a-decline-the-first-in-years.html?abt=0002&abg=1. However, medical bankruptcies are not expected to be entirely eliminated because even if everyone has insurance, not all expensive medical treatments are insured.

Hadley et al. (2008) estimate that uncompensated care provided by hospitals accounts for approximately 5 % of their revenues. Most of this expense is covered by public funds (reimbursement), that is, by tax revenues. Our results are neutral to the form of funding as long as the net subsidies for health care provided through bankruptcy are progressive. We elaborate on this point in the discussion.

Summers (1989) previously considered physician willingness to provide medical care on credit (or the inability to avoid such care) as a justification for health insurance mandates.

That is, underconsumption of medical care by some imposes disutility on others (who consume more), as noted by Gruber (2008) and Summers (1989).

In our model, the legal requirement to provide medical care on credit and the bankruptcy system set effective limits on consumers’ liability for their medical debts.

Due to social policies that guarantee a minimum wealth and that lack punishments in cases of insufficient wealth to compensate for damages.

Therefore, the uninsured driver may not only gain from his own limited liability but also lose from being exposed to the limited liability of other uninsured drivers over the risk they impose.

In our model, income coincides with initial wealth.

That is, marginal utility is convex in consumption (see Kimball 1990). Prudence is required for decreasing absolute risk aversion. Leland (1968) showed that prudence implies that optimal saving increases with income uncertainty, thereby formalizing the precautionary motive for saving. For more implications of prudence, see Eeckhoudt and Schlesinger (2006).

We deliberately abstract from all distortions associated with imperfect information in both insurance markets and bankruptcy systems. Nonetheless, we have considered some possible implications of Moral Hazard in the Introduction and will discuss possible implications of Adverse selection in Sect. 5.

To enhance tractability, the analysis presented here introduces medical risk only. In an earlier and extended version of the paper, we showed that adding non-contractible income risk does not change our main results.

As the analysis is confined to full insurance on the intensive margin (zero co-pays), we will use the term “insurance coverage” to refer to the rate of insured consumers (i.e., the extensive margins).

In this model, bankruptcy provides full insurance for free (fully discharged bills) for consumers with income \(w<X\). Hence, they cannot benefit from standard insurance and will never pay for it.

Hadley et al. (2008) report that 75 % of the uncompensated care provided by hospitals is funded through federal transfers. Nonetheless, the price loading in our model is equivalent to a lump-sum tax levied by the policy maker to reimburse consumer defaults on medical bills.

Inequality (4) implies that, as long as bankruptcy is an effective option (i.e. \(w-M<X\)), the maximal willingness to pay for health insurance increases in income, but with a coefficient that is lower than one. The convexity of \(\widetilde{w}(m)\), due to prudence, implies that this rate of increase in the (maximal) willingness to pay for insurance is decreasing. The maximal willingness to pay for insurance is equivalent to the risk-premium as defined by Pratt (1964). His analysis shows that prudence (implies a negative relation between wealth and the risk premium. However, his analysis focuses to a common risk in all wealth levels, whereas here financial risk increases in wealth as a decreasing share of medical expenses can be waved under bankruptcy. Sinn (1982, p. 160) reports a similar result regarding consumers’ insurance converge choice under limited liability, on the intensive margins.

For sufficiently large MC, the \(m\left( \widetilde{w}\right) \) curve is entirely below the \(\widetilde{w} \left( mc\right) \) curve. Thus, there is no equilibrium in the market: the insurance take-up level is always too low to support non-negative profits for health care providers.

\(\frac{d}{dy} {\displaystyle \int \limits _{g_{1}\left( y\right) }^{g_{2}\left( y\right) }} f\left( x,y\right) dx= {\displaystyle \int \limits _{g_{1}\left( y\right) }^{g_{2}\left( y\right) }} \frac{df}{dy}f\left( x,y\right) dx+g_{2}^{\prime }\left( y\right) f\left( g_{2}\left( y\right) ,y\right) -g_{1}^{\prime }\left( y\right) f\left( g_{1}\left( y\right) ,y\right) \)

The ACA exempts annual penalties if bankruptcy was filed during the first six months of the year.

In principle, the budget constraint should include revenues from penalty payments made by the remaining uninsured. However, as we confine our attention to effective policies, those payments are practically zero by Definition 1.

This line is illustrative and should not be linear. Its actual slope is given by \(\frac{\partial t_{\min }}{\partial s_{\min }}=-\frac{u^{\prime }\left( w-m+s\right) }{\left( 1-\pi \right) u^{\prime }\left( w-t\right) +\pi u^{\prime }\left( X-t\right) }\).

Source: CBO estimations at http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/amendreconprop.

Hence, premiums are set according to the average probability.

References

Beard, T. R. (1990). Bankruptcy and care choice. The RAND Journal of Economics, 21, 626–634.

Coase, R. (1960). The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3, 1–44.

Cook, K., Dranove, D., & Sfekas, A. (2010). Does major illness cause financial catastrophe? Health Service Research, 45, 418–436.

Dranove, D., & Millenson, M. L. (2006). Medical bankruptcy: myth versus fact. Health Affairs, 25, W74–W83.

Ehrlich, I., & Becker, G. S. (1972). Market insurance, self-Insurance and self protection. Journal of Political Economy, 80, 623–649.

Eeckhoudt, L., & Schlesinger, H. (2006). Putting risk in its proper place. American Economic Review, 96, 280–289.

Gross, T., & Notowidigdo, M. J. (2011). Health insurance and the consumer bankruptcy decision: Evidence from expansions of Medicaid. Journal of Public Economics, 95, 767–778.

Gruber, J. (2008). Covering the uninsured in the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 46, 571–606.

Gruber, J. (2011). The impacts of the Affordable Care Act: How reasonable are the projections?. NBER working paper 17168

Hadley, J., Holahan, J., Coughlin, T., & Miller, D. (2008). Covering the uninsured in 2008: Current costs, sources of payment, and incremental costs. Health Affairs, 27, 399–415.

Himmelstein, D. U., Warren, E., Thorne, D., & Woolhandler, S. (2005). Illness and injury as contributors to bankruptcy. Health Affairs, 24, W65–W73.

Himmelstein, D., Thorne, D., Warren, E., & Woolhandler, S. (2009). Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: Results of a National Study. The American Journal of Medicine, 122, 741–746.

Jaspersen, J. G., & Richter, A. (2015). The wealth effects of premium subsidies on moral hazard in insurance markets. European Economic Review, 77, 139–153.

Keeton, W. R., & Kwerel, E. (1984). Externalities in automobile insurance and the underinsured driver problem. The Journal of Law & Economics, 27, 149–179.

Kimball, M. S. (1990). Precautionary saving in the small and in the large. Econometrica, 58, 53–73.

Leland, H. E. (1968). Saving and uncertainty: The precautionary demand for saving. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 82, 465–473.

Mahoney, N. (2015). Bankruptcy as implicit health insurance. American Economic Review, 105, 710–746.

Mazumder, B., Miller, S. (2015). The effects of the Massachusetts Health Reform on financial distress. Forthcoming in American Economic Journal: Economic Policy.

Miller, W., Vigdor, E. R., & Manning, W. G. (2004). Covering the uninsured: What is it worth? Health Affairs, 4, 157–167.

Pratt, J. W. (1964). Risk aversion in the small and in the large. Econometrica, 32, 122–136.

Shavell, S. (1986). The judgment proof problem. International Review of Law and Economics, 6, 45–58.

Sinn, H. W. (1982). Kinked utility and the demand for human wealth and liability insurance. European Economic Review, 17, 149–162.

Summers, L. H., (1989). Some simple economics of mandated benefits. American Economic Review, 79, 177–183.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We have benefited from comments provided by a referee of this journal, Randy Beard and Melissa Oney, as well as by participants at the 2014 Southern Economics Association conference in Atlanta GA and at the 2015 International Health Economics Association conference in Milan, Italy.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof for Lemma 1

\(\frac{\partial \Delta }{\partial w_{i}}=u^{\prime }\left( w_{i}-m\right) -\left( 1-\pi \right) u^{\prime }\left( w_{i}\right) >0\). That is the gain from insurance is increasing monotonically with income. For \(w_{L}=X\) :\(\Delta <0\), and for \(w>X+M:\Delta <0\). Thus, due to the continuity of (1) \(\exists \widetilde{w}\in \left( X,X+M\right) \) s.t \(\forall w<\widetilde{w} :\Delta <0\) and \(\forall w>\widetilde{w}:\Delta >0\). \(\square \)

Proof for the convexity of \(\widetilde{w}(m)\): Convexity of \(\widetilde{w}(m)~\)implies that \(\frac{d\widetilde{w}}{dm}\) is positive and increasing. Equation (4) \(\frac{d\widetilde{w}}{dm} =\frac{u^{\prime }\left( \widetilde{w}-m\right) }{u^{\prime }\left( \widetilde{w}-m\right) -\left( 1-\pi \right) u^{\prime }\left( \widetilde{w}\right) }>1\) can be written as

The above expression is increasing with m, that is \(\frac{d\widetilde{w} }{dm^{2}}>0\) iff \(\frac{d\frac{\left( 1-\pi \right) u^{\prime }\left( \widetilde{w}\right) }{u^{\prime }\left( \widetilde{w}-m\right) }}{dm}>0\). Deriving \(\frac{d\widetilde{w}}{dm^{2}}\) explicitly we obtain

Applying \(\frac{d\widetilde{w}}{dm}=\frac{1}{1-\frac{\left( 1-\pi \right) u^{\prime }\left( \widetilde{w}\right) }{u^{\prime }\left( \widetilde{w} -m\right) }}\) to (9) elaborates it to

The sign of (10) is determined by the expression in the brackets. It is negative if

For (11) to be negative,—implying \(\frac{d\widetilde{w}}{dm^{2}}>0\)—it is sufficient to have \(u^{{\prime \prime }}\left( \widetilde{w}\right) >u^{{\prime \prime }}\left( \widetilde{w}-m\right) \) that is \(u^{{{\prime \prime \prime }}}\left( \cdot \right) >0\). \(\square \)

Proof for Lemma 2:

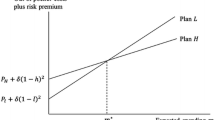

By (2a) \(\frac{dm}{dMC}>0\) for any given uninsured level \(\widetilde{w}\). Hence, by (4), \(\frac{d\widetilde{w}}{dMC}>0\) that is insurance take-up level is also decreasing with MC. For \(MC\rightarrow 0:\frac{d\widetilde{w}}{dm}\rightarrow 1\) and \(\frac{dm}{d\widetilde{w}}<1\) hence an intersection between (2a) and (3), denoted \(E_{L}\left( \widetilde{w}_{L}^{E},m_{L} ^{E}\right) \), is guaranteed. However, as \(\widetilde{w}\) increases \(\frac{dm}{d\widetilde{w}}\longrightarrow \infty \), guaranteeing a second intersection \(E_{H}\left( \widetilde{w}_{H}^{E},m_{H}^{E}\right) \), where \(\widetilde{w}_{L}^{E}<\) \(\widetilde{w}_{H}^{E}\) and \(m_{L}^{E}<m_{H}^{E} \). \(\square \)

Proof for Lemma 3:

Any insurance coverage level set by the policy maker, \(\overline{w}\) implies a corresponding insurance premiums determined by (2a) and the \(m\left( \overline{w}\right) \) curve in Diagram 1.\(\forall \overline{w}\notin \left( w_{L}^{E},w_{H}^{E}\right) \) the \(m\left( \overline{w}\right) \) curve is below \(\varphi \left( \overline{w},m\right) \), implying that for the break-even premiums the marginal consumer \(\overline{w}\) would prefer being uninsured, hence \(SMU>0\). The converse is true for \(\overline{w}\in \left( w_{L}^{E},w_{H}^{E}\right) \) as the \(m\left( \overline{w}\right) \) curve is above \(\varphi \left( \overline{w},m\right) \), implying the marginal consumer \(\overline{w}\) would prefer to be insured for the corresponding market premiums, hence \(SMU<0\). \(\square \)

Proof for Proposition 3:

\(\forall \psi ^{pigov}\left( t,s\right) :\left( 1-\pi \right) \left( w_{i}\right) +\pi X-t_{i}=w_{i}-\left( m-s_{i}\right) \Rightarrow t_{i}+s_{i}=\pi \left( M+X-w_{i}\right) \). By Definition 2, all Pigovian incentives equalize expected consumption with and without insurance. Hence, in face of the Pigovian incentive put by any Pigovian policy all risk-averse consumer strictly prefers buying insurance. Then, as everyone is insured \(P=MC\) (by 2a). The subsidies cost under Pigovian policy cannot exceed the cost of subsidizing medical care through bankruptcy: \(\forall \psi ^{pigov}\left( t,s\right) :\) \( {\displaystyle \int \nolimits _{w_{L}}^{w^{E}}} s_{i}di\le \frac{1}{F\left( w^{e}\right) } {\displaystyle \int \nolimits _{w_{L}}^{w^{E}}} p_{i}(M^{E}+X-w_{i})di\) . Hence any Pigovian Policy can indeed be funded through a tax \(\tau \le \left( m^{E}-mc\right) \) on the initially insured, without making them drop their insurance. \(\square \)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sorek, G., Benjamin, D. Health insurance mandates in a model with consumer bankruptcy. J Regul Econ 50, 233–250 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-016-9302-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-016-9302-x