Abstract

Whether household wealth affects labor market behavior is an important empirical question in economics. As the literature only discusses the effect of the absolute value of housing wealth on homeowners’ labor supply, this paper studies how a homeowner’s relative housing wealth—i.e., perceived housing wealth gain compared with their reference group-affects labor market behavior. Using China’s housing boom as a natural experiment, we first construct homeowners’ reference housing wealth using the hedonic method and then estimate the effect of homeowners’ relative housing wealth on labor supply. Subsequently, we identify a causal effect of relative housing wealth on homeowners’ labor supply using an instrumental variable approach and find that an appreciation in relative housing wealth does not significantly influence homeowners’ employment, but significantly reduces their working hours. Our results show that this reduction in working hours is mainly driven by female homeowners. Our results also suggest that the effects of relative housing wealth vary across educational backgrounds, marital statuses, and locations. We find that the effect is more pronounced for female homeowners who are less educated, married, and living in rural areas. Moreover, a set of robustness checks corroborates the validity of our identification strategies and tests the sensitivity of the results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In China, the regular work day is 8 hours.

Agarwal (2007) adopts a unique US data set and finds that ex ante, homeowners who rate (cash-out) refinance an existing loan to increase savings (consumption) are significantly more likely to underestimate (overestimate) their house value, and overestimators (underestimators) are more likely to increase (reduce) their spending ex post. Campbell and Cocco (2007) use UK micro-data and find a positive relationship between housing wealth and consumption. Yang and Wang (2012) show a negative relationship between housing wealth and consumption using data from Sweden. Mian et al. (2013) suggest that housing wealth positively affects consumption in the US. Dong et al. (2017) find that the housing price has a wealth effect and a substitution effect on consumption in China and show that the wealth effect is significant if the housing price-to-income ratio is below 5.0882 and the indicator of financial development is above 1.8827. They also find that the substitution effect will become dominant if the housing price-to-income ratio lies between 5.0882 and 5.9625.

Please refer to Chen and Wen (2017) for details.

The calculation of reference housing wealth will be discussed in Section “Hedonic Analysis”.

The CHNS has no information on transaction prices for homeowners’ properties. Self-reported housing wealth is the only homeowner’s housing value in the survey.

In our dataset, self-reported housing wealth is the same for each member of a household, so household fixed effects can sufficiently alleviate concerns about misestimation of housing wealth.

Housing quality and location are not available in the CHNS data.

According to our dataset, in a typical double-income family the male homeowner’s individual income is about 57.5% of total household income.

The CHNS started to collect home mortgage data in 2009. The relevant variables in the survey are as follows: (1) Do you have a mortgage? (2) What is your monthly payment? (3) What is your down payment? In our sample, only 7.3% of individuals in our sample have home mortgages. Thus, we do not have sufficient information on home mortgages, such as mortgage balance, refinance rate, and cash-out refinance, to perform a rigorous analysis for the effects of home mortgages on labor supply.

According to our dataset, a less-educated homeowner’s individual income is about 54% of a well-educated homeowner’s individual income.

We also investigate the effects of reference and relative housing on other economic behaviors, including early retirement and housewife decision. Results are reported in Appendix Table 11. We find that the coefficient of relative housing wealth is statistically significant for early retirement only in the male sample.

References

Abel, A. B. (1990). Asset prices under habit formation and catching up with the Joneses. The American Economic Review, 80(2), 38.

Agarwal, S. (2007). The impact of homeowners’ housing wealth misestimation on consumption and saving decisions. Real Estate Economics, 35(2), 135–154.

Akerlof, G. A. (1982). Labor contracts as partial gift exchange. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 97(4), 543–569.

Akerlof, G. A., & Yellen, J. L. (1990). The fair wage-effort hypothesis and unemployment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 105(2), 255–283.

Bednarz, R. S. (1975). A hedonic model of prices and assessments for single-family homes: Does the assessor follow the market or the market follow the assessor?. Land Economics, 51(1), 21–40.

Butler, R. V. (1982). The specification of hedonic indexes for urban housing. Land Economics, 58(1), 96–108.

Bracha, A., Gneezy, U., & Loewenstein, G. (2015). Relative pay and labor supply. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(2), 297–315.

Campbell, J. Y., & Cocco, J. F. (2007). How do house prices affect consumption? Evidence from micro data. Journal of Monetary Economics, 54(3), 591–621.

Chamon, M., Liu, K., & Prasad, E. (2013). Income uncertainty and household savings in China. Journal of Development Economics, 105, 164–177.

Charles, K. K., Hurst, E., & Notowidigdo, M. J. (2018). Housing booms and busts, labor market opportunities, and college attendance. The American Economic Review, 108(10), 2947–94.

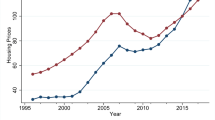

Chen, K., & Wen, Y. (2017). The great housing boom of China. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 9(2), 73–114.

Cole, H. L., Mailath, G. J., & Postlewaite, A. (1992). Social norms, savings behavior, and growth. Journal of Political Economy, 100, 1092–1125.

Cowling, K., & Cubbin, J. (1972). Hedonic price indexes for United Kingdom cars. The Economic Journal, 82(327), 963–978.

Del Boca, D., & Lusardi, A. (2003). Credit market constraints and labor market decisions. Labour Economics, 10(6), 681–703.

Deng, Y., Morck, R., Wu, J., & Yeung, B. (2011). Monetary and fiscal stimuli, ownership structure, and China’s housing market (No. w16871). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Dettling, L. J., & Kearney, M. S. (2014). House prices and birth rates: The impact of the real estate market on the decision to have a baby. Journal of Public Economics, 110, 82–100.

Disney, R., & Gathergood, J. (2018). House prices, wealth effects and labour supply. Economica, 85(339), 449–478.

Dong, Z., Hui, E. C., & Jia, S. (2017). How does housing price affect consumption in China: Wealth effect or substitution effect?. Cities, 64, 1–8.

Duesenberry, J. S. (1949). Income, savings and the theory of consumer behavior. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Fang, H., Gu, Q., Xiong, W., & Zhou, L. A. (2016). Demystifying the Chinese housing boom. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 30(1), 105–166.

Farnham, M., Schmidt, L., & Sevak, P. (2011). House prices and marital stability. The American Economic Review, 101(3), 615–19.

Fortin, N. M. (1995). Allocation inflexibilities, female labor supply, and housing assets accumulation: Are women working to pay the mortgage?. Journal of Labor Economics, 13(3), 524–557.

Fu, S., Liao, Y., & Zhang, J. (2016). The effect of housing wealth on labor force participation: Evidence from China. Journal of Housing Economics, 33, 59–69.

Gali, J. (1994). Keeping up with the Joneses: Consumption externalities, portfolio choice, and asset prices. Journal of Money Credit and Banking, 26(1), 1–8.

Glaeser, E., Huang, W., Ma, Y., & Shleifer, A. (2017). A real estate boom with Chinese Characteristics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1), 93–116.

Goodman, A. C. (1978). Hedonic prices, price indices and housing markets. Journal of Urban Economics, 5(4), 471–484.

Harrison, D. Jr, & Rubinfeld, D. L. (1978). Hedonic housing prices and the demand for clean air. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 5 (1), 81–102.

Hausman, J., & Taylor, W. (1981). Panel data and unobservable individual effects. Journal of Econometrics, 16(1), 155.

Hausman, J. A. (1996). Valuation of new goods under perfect and imperfect competition. In the economics of new goods (pp. 207-248). University of Chicago Press.

Henley, A. (2004). House price shocks, windfall gains and hours of work: British evidence. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 66(4), 439–456.

Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1982). Hedonic consumption: emerging concepts, methods and propositions. Journal of Marketing, 46(3), 92–101.

Huang, J. C., & Palmquist, R. B. (2001). Environmental conditions, reservation prices, and time on the market for housing. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 22(2-3), 203–219.

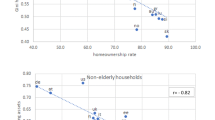

Jiang, X., Zhao, N., & Pan, Z. (2022). Regional housing wealth, relative housing wealth and labor market behavior. Journal of Housing Economics, 55, 101811.

Johnson, W. R. (2014). House prices and female labor force participation. Journal of Urban Economics, 82, 1–11.

Lancaster, K. J. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy, 74(2), 132–157.

Li, H., & Zhu, Y. (2006). Income, income inequality, and health: Evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 4(34), 668–693.

Li, L., & Wu, X. (2014). Housing price and entrepreneurship in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 42(2), 436–449.

Lovenheim, M. F., & Mumford, K. J. (2013). Do family wealth shocks affect fertility choices? Evidence from the housing market. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 464–475.

Malpezzi, S. (2002). Hedonic pricing models: a selective and applied review. Housing Economics and Public Policy. 67–89.

McBride, M. (2001). Relative-income effects on subjective well-being in the cross-section. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 45(3), 251–278.

Mian, A., Rao, K., & Sufi, A. (2013). Household balance sheets, consumption, and the economic slump. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(4), 1687–1726.

Mieszkowski, P., & Saper, A. M. (1978). An estimate of the effects of airport noise on property values. Journal of Urban Economics, 5(4), 425–440.

Mincer, J. (1958). Investment in human capital and personal income distribution. Journal of Political Economy, 66(4), 281–302.

Mok, H. M., Chan, P. P., & Cho, Y. S. (1995). A hedonic price model for private properties in Hong Kong. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 10(1), 37–48.

Moulton, B. R. (1996). Bias in the consumer price index: what is the evidence?. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(4), 159–177.

Murphy, K. J. (1999). Executive compensation. Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, 2485–2563.

Murphy, K. J. (2000). Performance standards in incentive contracts. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 30(3), 245–278.

Palmquist, R. B. (1984). Estimating the demand for the characteristics of housing. Review of Economics and Statistics, 66(3), 394–404.

Requena-Silvente, F., & Walker, J. (2006). Calculating hedonic price indices with unobserved product attributes: an application to the UK car market. Economica, 73(291), 509–532.

Rosen, S. (1974). Hedonic prices and implicit markets: product differentiation in pure competition. Journal of Political Economy, 82(1), 34–55.

Schultze, C. L. (2003). The consumer price index: Conceptual issues and practical suggestions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(1), 3–22.

Smith, B. (2000). Applying models for vertical inequity in the property tax to a non-market value state. Journal of Real Estate Research, 19(3), 321–344.

Smith, V. K., & Huang, J. C. (1995). Can markets value air quality? A meta-analysis of hedonic property value models. Journal of Political Economy, 103(1), 209–227.

Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. P. (2009). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr. Accessed 2018.

Summers, L. H. (1988). Relative wages, efficiency wages, and Keynesian unemployment. The American Economic Review, 78(2), 383–388.

Veblen, T. (1922). The theory of the leisure class: An economic study of institutions. George Allen & Unwin, London (first published 1899).

Wang, S. Y. (2011). State misallocation and housing prices: theory and evidence from China. The American Economic Review, 101(5), 2081–2107.

Wang, S. Y. (2012). Credit constraints, job mobility, and entrepreneurship: Evidence from a property reform in China. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(2), 532–551.

White, A. G., Abel, J., Berndt, ER., & Monroe, C. W. (2005). Hedonic price indexes for personal computer operating systems and productivity suites. Annals of Economics and Statistics, (79-80), 787–807.

Yang, Z., & Wang, S. T (2012). Permanent and transitory shocks in owner-occupied housing: A common trend model of price dynamics. Journal of Housing Economics, 21(4), 336–346.

Zhao, L., & Burge, G. (2017). Housing wealth, property taxes, and labor supply among the elderly. Journal of Labor Economics, 35(1), 227.

Acknowledgements

We thank Zan Yang, K.W. Chau, and Seow Eng Ong for their valuable comments and suggestions in the 2018 Asia Pacific Real Estate Research Symposium.

Xiandeng Jiang acknowledges the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72104204), and the PRC Ministry of Education Youth Project for Humanities and Social Science Research (Grant No. 20YJC790051). Zheng Pan acknowledges financial support from the Project of Philosophy and Social Sciences of Guangdong Province (Grant No. GD20CYJ17).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Author Xiandeng Jiang has received the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72104204), and the PRC Ministry of Education Youth Project for Humanities and Social Science Research (Grant No. 20YJC790051). Author Zheng Pan has received the financial support from the Project of Philosophy and Social Sciences of Guangdong Province (Grant No. GD20CYJ17).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, X., Pan, Z. & Zhao, N. Relative Value vs Absolute Value: Housing Wealth and Labor Supply. J Real Estate Finan Econ 66, 41–76 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-022-09904-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-022-09904-1